Abstract

A shelf stable, convenience product egg yolk paneer (EYP) was developed by incorporation of optimized quantities of binders, salt, natural antioxidants and egg yolk. Dehydrated EYP was packed in metalised polyester pouches, stored at ambient temperature (27 ± 2 °C) for 6 months and sampled periodically for quality evaluation. The protein and fat content of dehydrated EYP was 26.2 ± 1.75% and 36.1 ± 2.46, respectively. The shelf stability of the product was achieved by keeping a moisture content (5.6 ± 0.50%) and water activity (0.43 ± 0.05) low. An excellent rehydration capacity (64.8 ± 5.39%) was observed in the EYP, whereas, the rehydration ratio of the product was 1:2.7. Changes in Free Fatty Acids, Thiobarbituric acid, textural profile analysis and Hunter colour units (L, a and b) during storage did not affect the quality characteristics of the product. About 38% loss in carotenoid content was recorded during storage of the product. Staphylococcus aureus, E coli, Salmonella and Shigella, however, were not detected in any sample throughout the storage period. Sensory evaluation revealed that rehydrated yolk paneer had excellent texture and was very close to fresh ones (before drying) during storage for 6 months.

Keywords: Egg yolk, Paneer, Rehydration, Textural quality, Hunter colour, Carotenoids

Introduction

Egg is a good source of low-cost high-quality protein. Generally egg yolk is used in cooking for mayonnaise, custard, hollandaise sauce, avgolemono and ovos-moles. With increasing egg production and subsequent impact on the market, the industry has realized the importance of creating demand for processed egg products. Information is available on different egg products, such as egg coated potato (Muller 1994), premixed flavoured egg product (Wu et al. 1995), egg flakes containing monosodium glutamate and onion/garlic extracts (Lee et al. 1998), egg white chips containing stabilizers and flavouring (Yang et al. 2000), formulated fried egg (Merkle et al. 2003), egg loaf containing spices and refined wheat flour (Yashoda et al. 2004), egg albumen cube and egg yolk cube (Modi et al. 2008) and egg chips containing millet fours (Yashoda et al. 2007). A US patent for method of making egg and cheese product was filed by Heick et al. (1997). Research work by the South African Egg Board on new egg products, viz., egg and bacon patty, bite-sized egg snacks, frozen egg pizza and egg fingers (crumb-coated scrambled eggs and bacon bound by white sauce) has been reviewed by (Willense 1991).

Consumer today wants simple to prepare, convenient, healthy and natural foods. Egg yolk provides a viable option for these characteristics. Eggs contain important nutrients, especially the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D and E) essential fatty acids and minerals (Fe, Ca and Zn) (Anon 2010).

In view of the consumer’s nutritional needs, the egg yolk was used, for the development of egg yolk paneer (EYP). Egg yolk paneer can be used in curry preparation similar to paneer-in-curry, a delicacy in Indian cuisine. Paneer is an acid and heat coagulated milk product used extensively in India for various culinary preparations. Hence the objective of this work was to produce a shelf-stable dried product, which could be used conveniently for culinary preparations. The work reports on preparation of EYP and evaluation of its quality changes during storage at ambient temperature (27 ± 2 °C).

Materials and methods

Several trial formulations for development of EYP were attempted using different binders in order to obtain the product, which did not disintegrate (retain shape) during cooking in curry and sensory acceptability of the product. Optimized quantities (w/w) of ingredients of EYP are egg yolk, binders, natural antioxidant, common salt and permitted additives.

Product preparation

The mixing of dry ingredients, i.e. wheat flour (17.5%), maltodextrin (2.0%), salt (1.4%), garlic powder (1%) as a natural antioxidant, citric acid (0.05%) and malic acid (0.05%) was carried out in a Hobart mixer (Model M-50, USA) at low speed for 5–6 min to prepare binder mix (CFTRI Process know how). Hen eggs were procured from local market. The eggs were examined for their soundness. A batch of 100 eggs (50–55 g each), was broken over a sieve to separate albumin and yolk. Yolk paneer was prepared by mixing the egg yolk (78%) with standardized quantities of binder mix. The liquid egg yolk (1.90 kg) was mixed with a wire balloon whisk in Hobart mixer for 3–4 min at speed 2 to get the homogeneous liquid yolk. The binder mix was added slowly to homogenized liquid egg yolk while mixing continuously to obtain a batter with homogenous consistency. The mixing was carried out for 3–4 min till a uniform smooth batter was obtained. The mixing of binder mix and liquid yolk was carried out in two steps with a reason to uniform distribution of all the ingredients. The resultant batter was transferred to rectangular stainless steel moulds of 22 × 9 × 9 cm (l × b × h) dimension lined with polypropylene sheet and the product steamed at atmospheric pressure for 45 min (internal temperature 86 ± 2 °C) to obtain solidified product, followed by cooling at ambient temperature (27 ± 2 °C) for 30–45 min. The loaf was cut into cubes by using a cutting mould of 1 × 1 × 1 cm. size. The resultant pieces of EYP were then dried in cross flow dryer (C. M. Equipments & Instruments India Pvt. Ltd, Bangalore, India) by spreading in stainless steel trays at the rate of 1 kg/m2. The drying was carried out at 85 ± 3 °C to obtain dried pieces. The dried EYP were allowed to cool.

Storage studies

The product was packed in metalized polyester (polyester 10–11 micron/aluminum foil 9–12 micron/polythene 100 gauges) bags of 50 g capacity each and stored at ambient temperature (27 ± 2 °C). The stored products were drawn periodically for 6 months for quality evaluation.

Physico-chemical properties

The percentage yield on drying of the product was determined by weighing the EYP before and after drying. The percent increase in the volume after rehydration was determined by measuring the area (l × b × h) of EYP pieces before and after rehydration by using the Eq. 1. An average of six measurements was recorded:

|

1 |

Rehydration was carried out following the procedure described by (Ranganna 1995) with some modifications. Ten gram sample was placed in 500 ml beaker, 300 ml of distilled water was added and covered with watch glass, brought to a boil within 2 min and boiled for 4 min. Temperature of the heater was controlled to avoid excess boiling and evaporation of water. The samples were removed from the heater and transferred into a 100 mm glass funnel, drained for 2 min until the drip from the funnel has stopped, removed from the funnel and weighed. Drained rehydrated EYP samples were used for textural profile analysis.

Rehydration ratio and percent rehydration in terms of percent water in rehydrated paneer were calculated as described by (Ranganna 1995) with a modification (Eq. 2 and 3).

Rehydration ratio:

|

2 |

Percent water in the rehydrated paneer (Rehydration,%):

|

3 |

Bulk density of the product was determined by filling the product to the rim of 500 ml graduated cylinder and weighing the sample filled in cylinder. The results were expressed as g/cc.

Proximate composition

About 50 g of dried paneer samples was powdered using mortar and pestle. The powder was used for chemical analysis. Moisture, protein, fat, salt content and ash contents were determined according to AOAC (2007) procedures. Carbohydrate was calculated by difference. Ten gram of EYP powder in a beaker was stirred with 90 ml distilled water and pH measured by immersing combined glass-calomel electrode directly in a mixture using pH meter (Control Dynamic, APX 175 E/C, Bangalore India). Water activity (aw) was measured using water activity meter (AquaLab 3TE, Decagon Devices Inc., Washington, USA). An average of four measurements was taken.

Rancidity parameters

Free fatty acid (FFA), a sample (10 g) was mixed with anhydrous Na2SO4 (100 g) and fat was extracted in 100 ml solvent mixture of chloroform and methanol (2:1) and filtered. A known volume of chloroform: methanol extract was then washed three times with four to five volumes of distilled water in a separating funnel to remove non fatty acids that may have come from formulation ingredients. The FFA as percentage of oleic acid was estimated in washed chloroform: methanol extract using AOAC (2007) procedure. Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was determined by the method of Tarladgis et al. (1960).

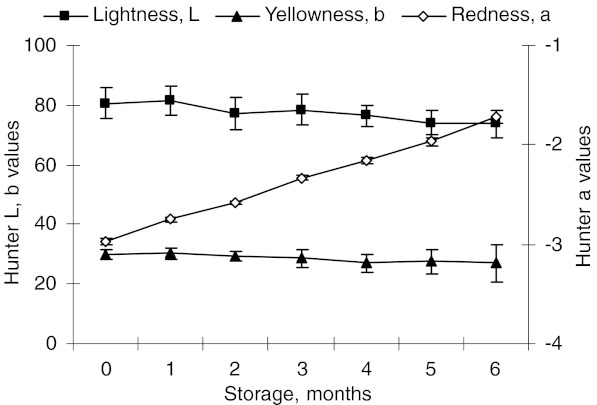

Instrumental colour measurements

Colour of dehydrated samples was measured using Hunter Colour Measuring System (Labscan XE, Hunter Associates Laboratory Inc., Virginia, USA) at 2° view angle. The Hunter colour measuring system was standardised with a white tile (L = 90.4, a = −0.98 and b = 1.05). Colour was described as coordinates, e.g. L, a and b (where L measures relative lightness, a relative redness, and b relative yellowness).

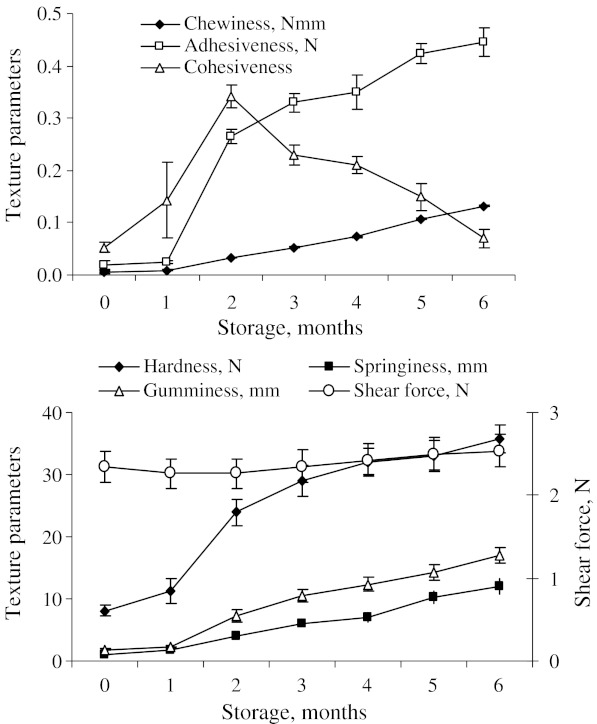

Texture profile analysis

Rehydrated EYP samples were subjected to texture profile analysis and shear force using a Texture Analyzer (LR5K, LLOYD Instruments Ltd, Hampshire, UK). The rehydrated samples were placed on the platform of texture analyzer. A cylinder plunger of 32 mm diameter attached to a 1 KN load cell and sample (10 mm cube) was compressed to 50% of its original height at a cross head speed of 100 mm/min twice in two cycles. The texture parameters viz. hardness (N), cohesiveness, springiness (mm), Chewiness (Nmm), adhesiveness (N) and gumminess (N) were measured. Shear force was measured by applying a load of 50 Newton with a speed of 100 mm/min using triangle probe. The values were recorded based on the software, Nexigen version 6.0 (Lloyd Instruments Ltd, Hampshire, England) available with the instrument. The mean value of six readings for each texture profile is reported.

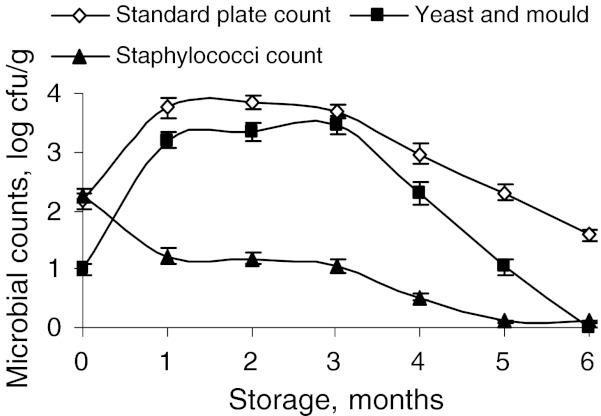

Microbiological analysis

A 10 g sample of dried EYP was placed in a sterile stomacher bag containing 90 ml of sterile saline (0.85% NaCl) solution and blended in Stomacher (Model SEWARD Stomacher 400, London, England). The blended samples were tested for standard plate counts (SPC), Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella and yeast and molds by spread plate and pour plate method as per APHA (2001) procedures.

Sensory quality evaluation

Dehydrated EYP samples were used for the preparation of curry by using optimum quantities of spices and condiments. The curry contained chopped onion, ginger paste, garlic paste, green chillies, tomato puree, fresh coriander leaves, red chilly powder, coriander powder, turmeric powder and garam masala powder (a combination of cardamom, clove, cinnamon, cumin and black pepper). The dried EYP were added in hot cooked curry. The curry with EYP was further cooked for 2–3 min. The EYP samples in curry were evaluated for sensory quality for appearance (shape retention), color, flavour, texture, juiciness and overall acceptability by 8 in-house trained panelists using 9-point Hedonic scale (Andres et al. 2006). The product was presented to panelists at 60 ± 5°C in coded white ceramic plates. The mean scores for each attributes are reported.

Statistical analysis

The experiment was carried out in 4 batches (n = 4). The mean of all parameters were examined for significance (p ≤ 0.05) by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and mean separation and the significant effect was tested by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test using software STATISTICA (Statsoft 1999).

Results and discussion

Product optimization

During optimization of ingredient levels, care was taken that the product is not disintegrated during rehydration or cooking in gravy. Based on the textural properties of rehydrated product and judged by sensory evaluation, it was found that the use of different binders in combination (wheat flour and maltodextrin) improved texture and rehydration properties. The photographs of dehydrated and rehydrated EYP are presented in Fig. 1.The selected binders also helped in generation of egg yolk froth which did not allow the settling of ingredients during processing. The yield of the dried product was 55.2 ± 2.40%.

Fig. 1.

Changes in Hunter colour unit values of egg yolk paneer during storage at ambient condition (27 ± 2 °C) (n = 4)

Proximate composition

The shelf stability of the product was achieved by keeping low moisture content (5.6 ± 0.50%) and low aw (0.43 ± 0.05) (Table 1). The protein content was 26.2 ± 1.75% and fat content was 36.1 ± 2.46%. Shelf stable dried flake shaped egg products prepared from liquid egg using common salt, monosodium glutamate, garlic and onion extract had aw in the range of 0.20–0.50 with moisture content of 4.1–8.3% (Lee et al. 1998).

Table 1.

Yield and physico-chemical properties of the dehydrated egg yolk paneer

| Moisture,% | 5.6 ± 0.50 |

| Ash,% | 5.2 ± 0.33 |

| Protein,% | 26.2 ± 1.75 |

| Total fat,% | 36.1 ± 2.46 |

| Salt,% | 4.2 ± 0.12 |

| Carbohydrate by difference,% | 27.7 ± 0.61 |

| Bulk Density, g/cc | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| Increase in volume on rehydration,% | 51.0 ± 4.76 |

| Rehydration,% | 64.8 ± 5.39 |

| Rehydration ratio | 1:2.7 ± 0.26 |

| Water activity | 0.43 ± 0.05 |

| Yield after drying,% | 55.2 ± 2.40 |

(n = 4)

Rehydration properties

Samples had a high degree of rehydration. A 51.0 ± 4.76% increase of volume with 64.8 ± 5.39% of rehydration was observed in EYP (Table 1). The increase in volume was due to high rehydration ratio (1:2.7–1:2.8) (Table 1) of the product. The bulk density of the product was 0.14 ± 0.01 g/cc. The low value of density also indicated that the product is very light in weight due to porous structure and hence allowed more water absorption on rehydration. Modi et al. (2008) reported that the greater absorption of water by the product could also be due to its very low moisture content (5.6 ± 0.50) (Table 1).

Rancidity parameters

The fall in pH from 5.9 ± 0.16 to 5.4 ± 0.14 in dehydrated EYP (Table 2) during 6 months storage was marginal (p ≥ 0.5). Freshly prepared products had low FFA values (as% oleic acid) of 1.2 ± 0.11%, which gradually increased (p ≥ 0.5) to 1.5 ± 0.25% during 6 months of storage. Increase in FFA due to lipase action in food products during storage is well documented and this increase did not increase the rancidity of food products prepared by using spice ingredients, such as pork sausages (Fernandez and Rodriguez 1991; Zalacain et al. 1995), buffalo meat burgers (Modi et al. 2003), egg loaf (Yashoda et al. 2004), and chicken curry (Modi et al. 2005). The oxidative rancidity measured by TBA values (mg malonaldehyde/kg sample) also showed an ascending trend (p ≥ 0.05) from the initial values of 2.2 ± 0.28 to 3.3 ± 0.12 during 6 months storage (Table 2). The increase in TBA values could be due to increased lipid oxidation and production of volatile metabolites in the presence of oxygen due to aerobic packaging and storage. Increase in TBA values during storage is reported in fried egg yolk cubes (Modi et al. 2008) and in egg loaf (Yashoda et al. 2004). On the contrary in spite of high contents of fat in the product, the increase in oxidation was found marginal (p ≥ 0.05). This could be due to presence of carotenoids providing antioxidant protection to the product. (Woodall et al. 1997, Surai and Speake 1998). At the end of 6 months of storage about 38% loss in carotenoid content was recorded. Wenzel et al. (2010) reported, after the 6 months of storage, the contents of carotenoids in the egg yolk powder were significantly lower. Similar observations were made by Tavarini et al. (2007) during storage of Kiwi fruit.

Table 2.

Changes in chemical properties of dehydrated egg yolk paneer during storage under ambient conditions (27 ± 2 °C)

| Storage period, Months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Moisture,% | 5.6 ± 0.50a | 5.3 ± 0.68a | 5.5 ± 0.60a | 5.6 ± 0.91a | 5.4 ± 1.06a | 5.2 ± 0.76b | 4.8 ± 0.96c |

| pH | 5.9 ± 0.16a | 5.7 ± 0.21a | 5.6 ± 0.19a | 5.6 ± 0.16a | 5.5 ± 0.14a | 5.6 ± 0.13a | 5.4 ± 0.14a |

| TBA, mg malonaldehyde/kg | 2.2 ± 0.28a | 2.2 ± 0.21a | 2.6 ± 0.37b | 2.9 ± 0.10c | 3.1 ± 0.27cd | 3.2 ± 0.21de | 3.3 ± 0.12e |

| FFA,% oleic acid | 1.2 ± 0.11a | 1.4 ± 0.14b | 1.4 ± 0.22b | 1.4 ± 0.28b | 1.5 ± 0.36b | 1.5 ± 0.28b | 1.5 ± 0.25b |

| Carotenoid, μg/g | 12.9 ± 1.43a | 11.7 ± 1.33ac | 11.0 ± 1.09ce | 10.2 ± 1.20de | 9.6 ±0.73d | 8.7 ± 1.05f | 7.9 ± 0.96f |

Values in rows with different superscripts differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) (n = 4)

Hunter colour values

Colour reflectance values measured on Hunter colour measuring system revealed a decrease (p ≤ 0.05) in L values of EYP from 80.7 ± 5.27 to 73.7 ± 4.79 and a values increased (p ≤ 0.05) from −3.0 ± 0.03 to −1.7 ± 0.07 during 6 months storage (Fig. 1), whereas, changes in b values were marginal (p ≥ 0.5). Changes in chroma and Hue-angle values were in narrow range (p ≥ 0.5) from 30.2 to 26.7 and −84.3 to −86.2 respectively after 6 months of storage. Changes in visual colour values are influenced by method of processing (Pesek and Wilson 1986), degree of exposure to light (Kim et al. 2002) and interaction of ingredients (Osuna-Garcia et al. 1997). There was no definite trend changes in Hunter L, a and b values during storage of fried egg yolk cubes (Modi et al. 2008). However, Bergquist (1995) observed that browning reaction does not occur very rapidly in egg products containing carbohydrates. In the present investigation, despite changes in instrumental chromatic attributes (L, a and b values), the visual colour appearance of EYP products was quite acceptable even after 6 months storage at ambient conditions. There was no definite trend in changes in Hunter L, a and b units during storage of deep fat fried egg albumen and egg yolk cubes Modi et al. (2008).

Textural profile

Hardness, springiness, adhesiveness and chewiness increased gradually (p ≤ 0.05) during storage, while cohesiveness increased up to 2 months and then decreased and changes in shear values were marginal (Fig. 2). Low adhesiveness in fresh samples could be due to rich foam formation during egg yolk beating for product preparation. The variation in texture of rehydrated EYP could be attributed to high rehydration ratio (more water absorption), which could impart a soft texture to the product (Ahmed et al. 1990, Keeton 1994).

Fig. 2.

Changes in textural profile of the egg yolk paneer during storage at ambient condition (27 ± 2 °C) (n = 4)

Microbiological quality

The SPC and yeast and mould counts increased (p ≤ 0.05) from 2.1 ± 0.14 to 3.8 ± 0.10 and 1.0 ± 0.09 to 3.4 ± 0.15 log cfu/g, respectively (Fig. 3) for first month followed by faster decrease up to 6 months. The Yeast and mould counts were not detected after 6 months of storage. Total Staphylococci counts were decreased gradually during storage. E coli, Salmonella and Shigella, however, could not be detected in samples throughout 6 months storage. Lower counts of mesophiles (SPC), yeasts and moulds; and, absence of Staphylococci aureus, E coli, Salmonella and Shigella may probably be due to thermal processing, low aw values of the product, hygienic practices followed during processing and storage and antibacterial effects of garlic (Grohs and Kunz 1999; Grohs et al. 2000) used in formulation. The results in the present investigation clearly indicate that the dehydrated EYP is microbiologically safe when packed in metalized polyester bags and stored at 27 ± 2 °C for 6 months.

Fig. 3.

Changes in microbial counts of egg yolk paneer during storage at ambient condition (27 ± 2 °C) (n = 4)

Sensory quality

Sensory score of 0 day product for all quality attributes were in the range of 7.6 ± 1.09–8.4 ± 0.45 which slowly decreased to 7.1 ± 1.26–7.9 ± 0.74 during storage for 6 months (Table 3). The egg flavour (p ≤ 0.05) in stored product was better as observed by panelists. However, a gradual increase in FFA and TBA values (Table 2) presumably explains the descending trends in ratings for overall sensory quality attributes (Modi et al. 2008).

Table 3.

Changes in sensory quality of egg yolk paneer during storage under ambient conditions (27 ± 2 °C)

| Storage period, Months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| AppearanceNS | 8.4 ± 0.45 | 8.1 ± 0.79 | 8.1 ± 0.76 | 7.9 ± 0.72 | 8.2 ± 0.51 | 7.8 ± 0.74 | 7.9 ± 0.74 |

| Colour | 8.2 ± 0.46a | 8.2 ± 0.56 a | 7.8 ± 0.68 b | 7.5 ± 0.78b | 7.4 ± 0.84 b | 7.3 ± 0.90 c | 7.1 ± 1.26 d |

| Flavour | 7.4 ± 0.41 a | 7.4 ± 0.66 a | 7.9 ± 0.82 b | 7.9 ± 0.22 b | 7.9 ± 0.41 b | 7.7 ± 0.31 b | 7.7 ± 0.47 b |

| TextureNS | 7.6 ± 1.09 | 7.6 ± 0.54 | 7.5 ± 0.46 | 7.4 ± 0.99 | 7.2 ± 1.48 | 7.4 ± 0.53 | 7.4 ± 0.66 |

| After tasteNS | 7.6 ± 0.81 | 7.9 ± 0.31 | 7.8 ± 0.39 | 7.8 ± 0.58 | 7.9 ± 0.23 | 7.8 ± 0.53 | 7.4 ± 0.29 |

| Overall acceptabilityNS | 7.7 ± 0.89 | 7.6 ± 0.65 | 7.6 ± 0.71 | 7.7 ± 0.86 | 7.7 ± 0.46 | 7.5 ± 0.42 | 7.5 ± 0.54 |

Values in rows with different superscripts differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) (n = 4)

NS Non significance

Conclusion

A convenience and ready-to-use product from egg yolk was prepared. The product packed in metalized polyester pouch had a shelf life of 6 months under ambient conditions (27 ± 2 °C). The sensorially acceptable and microbilogically safe product is similar to milk paneer, a traditional dairy product. In addition, the product does not contain any added preservative. The EYP can be used in traditional curry preparation.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Supra-Institutional Project (SIP) under the 11th five—year plan funded by CSIR. Thanks also to Appu Rao AG, Head, Protein Chemistry and Technology Department, for his valuable suggestions during research work.

References

- Anon (2010) Egg Yolks Would Resolve Americans’ Most Common Nutrient Deficiencies http://www.cholesterol-and-health.com/Egg_Yolk.html (Accessed on 01 April 2010)

- Ahmed PO, Miller MF, Lyon CE, Vaughters HM, Reagan JO. Physical and sensory characteristics of low fat fresh pork sausage processed with various levels of added water. J Food Sci. 1990;55:625–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb05192.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andres DK, Inz H, Szmanko T. Sensory quality of selected physicochemical properties of processed meat products produced in different plants. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2006;52:93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods. 4. Washington DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Official methods of analysis. 18. Washington DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist DH. Egg dehydratation. In: Stadelman WJ, Cotterill OJ, editors. Egg science and technology. 4. New York: Food Products Press; 1995. pp. 335–376. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MCD, Rodriguez IMZ. Lipolytic and oxidative changes in “Chorizo” during ripening. Meat Sci. 1991;29:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(91)90057-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohs BM, Kliegel N, Kunz B. Bacteria grow slower effects of spice mixtures on extension of shelf life of pork. Fleischwirtschaft. 2000;80:61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grohs BM, Kunz B. Antimicrobial effect of spices on sausage type Frankfurter. Adv Food Sci. 1999;21:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Heick JT, Case PE, Chawan DB (1997) Egg and cheese product and method of making same. US Patent US 5614244

- Keeton JT. Low fat meat products-technological problems with processing. Meat Sci. 1994;48:878–881. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Park JB, Hwang IK. Quality attributes of varieties of Korean red pepper powder (Capsicum annuum L.) and colour stability during sunlight exposure. J Food Sci. 2002;67:2957–2961. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb08845.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Yang SH, Chi SP. The development and quality evaluation of two-stages drum-hot air dried egg flakes. In: Effect of various egg yolk and egg white ratio and drying conditions. J Chin Soc Anim Sci. 1998;27:579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Merkle J, Ball H, Mathews J (2003) Formulation and process to prepare a formulated fried egg. US Patent US 0118714 A1

- Modi VK, Mahendrakar NS, Narasimha Rao D, Sachindra NM. Quality of buffalo meat burger containing legume flours as binders. Meat Sci. 2003;66:143–149. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi VK, Sachindra NM, Sathisha AD, Mahendrakar NS, Narasimha Rao D. Changes in quality of chicken curry during frozen storage. J Muscle Foods. 2005;17:141–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.2006.00034.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modi VK, Sheela PN, Mahendrakar NS. Egg albumen cubes and egg yolk cubes and their quality changes during storage. J Food Sci Technol. 2008;45:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Muller CL (1994) Method of preparing egg coated potato slices. US Patent US 5372830

- Osuna-Garcia JA, Wall MM, Waddell CA. Natural antioxidants for preventing colour loss in stored paprika. J Food Sci. 1997;62(5):1017–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1997.tb15027.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pesek CA, Wilson SA. Spice quality: Effect of cryogenic and ambient grinding on colour. J Food Sci. 1986;51:1386–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1986.tb13135.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganna S. Handbook of analysis and quality control for fruit and vegetable products. 2. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited; 1995. pp. 977–979. [Google Scholar]

- Surai P, Speake BK. Distribution of carotenoids from the yolk to the tissues of the chick embryo. J Nutri Biochem. 1998;9:645–651. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(98)00068-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statsoft (1999) Statistica for windows. Stasoft Inc. TULSA, USA

- Tarladgis BG, Walts BM, Younatahtan MT, Durgan JR. A distillation method for quantitative determination of malonaldehyde in foods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1960;37:44–48. doi: 10.1007/BF02630824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavarini S, Degl’Innocenti E, Remorini D, Massai R, Guidi L. Antioxidant capacity, ascorbic acid, total phenols and carotenoids changes during harvest and after storage of Hayward kiwifruit. Food Chem. 2007;107:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M, Seuss-Baum I, Schlich E. Influence of pasteurization, spray- and freeze-drying, and storage on the carotenoid content in egg yolk. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(3):1726–1731. doi: 10.1021/jf903488b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willense M (1991) Egg product ideas. South Africa, Poultry Int 30: 44, 46, 55–61

- Woodall AA, Britton G, Jackson MJ. Carotenoids and protection of phospholipids in solution or in liposomes against oxidation by peroxyl radicals: relationship between carotenoid structure and protective ability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1336:575–586. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(97)00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MY, Fann JI, Hsieh M, Yang SC. Studies on the development and shelf-life of premixed flavoured egg products. J Chin Soc Anim Sci. 1995;24:215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Yang SC, Lien TY, Liao MC. Investigation on processing conditions of vacuum- dried egg white chips and its quality evaluations. J Chin Soc Anim Sci. 2000;29:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yashoda KP, Jagannatha Rao R, Mahendrakar NS, Narasimha Rao D. Egg loaf and changes in its quality during storage. Food Control. 2004;15:523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2003.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yashoda KP, Modi VK, Jagannatha Rao R, Mahendrakar NS. Egg chips prepared by using different millet flours as binders and changes in product quality during storage. Food Control. 2007;19:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zalacain I, Zapelena MJ, Astiasaran I, Bello J. Dry fermented sausages elaborated with lipase from Candida cylincracea. Comparison with traditional formulations. Meat Sci. 1995;40:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(94)00023-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]