Summary

In mammals, precise placement of organs is essential for survival. We show here that inactivation of Roundabout (Robo) receptors 1 and 2 in mice leads to mispositioning of the stomach in the thoracic instead of the abdominal cavity, which likely contributes to poor lung inflation and lethality at birth, reminiscent of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) cases in human. Unexpectedly in Robo mutant mice, preceding organ misplacement and diaphragm malformation, the primary defect is a delayed separation of foregut from the dorsal body wall. Foregut separation is a rarely considered morphogenetic event and our data indicate that it occurs via repulsion of Robo-expressing foregut cells away from the Slit ligand source. In human, genomic lesion containing Robo genes has been documented in CDH. Our findings suggest that separation of the foregut from the body wall is genetically controlled, and defects in this event may contribute to CDH.

Introduction

The mammalian gut tube gives rise to both the respiratory and digestive systems (Domyan and Sun, 2011). In mature mammals, the respiratory system (trachea and lungs) is positioned within the thoracic cavity, while the majority of the digestive system with the exception of the esophagus is positioned within the abdominal cavity. Proper allocation of organs into their appropriate compartments is critical for survival. This requirement is highlighted in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), a life-threatening birth defect. In CDH, a portion of the abdominal organs protrude into the thoracic cavity, thereby preventing lung expansion at birth (Ackerman et al., 2005; Ackerman and Greer, 2007; Liu et al., 2003; Pober et al., 1993; Yuan et al., 2003). Despite the importance of proper segregation of organs into their respective cavities, relatively little is known about how this is achieved through development.

Evidence suggests that final organ position is not solely a reflection of where they are initially specified. For example, during early stages of foregut development (Embryonic day, or E9.75 in mouse), the lungs and stomach arise in close proximity to one another. Through a poorly understood process of differential growth and morphogenesis, the stomach gut tube rotates left and elongates posterior to the lungs. The subsequent formation of the diaphragm at E13.5 divides these two organs into separate cavities. Thus, precisely controlled morphogenesis of the organs is pre-requisite for their final position.

Roundabout (Robo) genes encode cell-surface receptors that respond to their secreted ligands, Slit proteins, in a wide variety of cellular processes (reviewed in Long, et al., 2004; Ypsilanti et al., 2010). Four Robo genes and three Slit genes have been identified in the mouse genome (Brose et al., 1999; Kidd et al., 1998). First implicated in regulation of axon pathfinding (Kidd et al., 1998; Kidd et al., 1999; Rothberg et al., 1988), Slit-Robo signaling has since been demonstrated to play a role in processes such as neural crest cell migration and sensory ganglia morphogenesis (De Bellard et al., 2003; Shiau and Bronner-Fraser, 2009), leukocyte chemotaxis (Ye et al., 2010), epithelial adhesion (Macias et al., 2011), and diaphragm and kidney formation (Grieshammer et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 2003). Functionally, Slit-Robo signaling has been shown to transmit migratory cues by modulating cell adhesion and actin polymerization (Lundstrom et al., 2004; Rhee et al., 2002; Rhee et al., 2007; Shiau and Bronner-Fraser, 2009). These cues are largely repulsive, although they can be attractive or promote growth and branching in some cellular contexts (Englund et al., 2002; Ma and Tessier-Lavigne, 2007; Wang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003; Ye et al., 2010). Homophilic interactions between Robo receptors have also been shown to regulate cell-adhesion and migration (Hivert et al., 2002).

In this study we report an unexpected requirement for Robo genes in foregut morphogenesis. Mice that are deficient in Robo1 and Robo2 (Robo1;2) fail to inflate their lungs and die at birth. Accompanying these defects, their stomach protrudes through the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity. These phenotypes are reminiscent of the diaphragmatic hernia defect previously reported in the Slit3 mutant mice (Liu et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 2003). The hernia phenotype in the Slit3 mutant was attributed to a primary defect in diaphragm formation. In this study, we demonstrate that the diaphragm defect in Robo as well as Slit mutant embryos is preceded by a delayed separation of foregut tube from the body wall. Our findings implicate Slit-Robo signaling as a key regulator of this poorly-understood foregut morphogenesis process.

Results

Perinatal lethality of Robo1;2 mutants

Multiple Robo and Slit genes are expressed in the embryonic foregut (Anselmo et al., 2003; Greenberg et al., 2004). To determine their potential roles in foregut development, we generated mice deficient for the principal receptor genes Robo1 and Robo2 (Robo1;2) using existing mutant alleles (Grieshammer et al., 2004; Long et al., 2004). Robo1 and Robo2 genes both reside on chromosome 16 about 1.1 centimorgans apart. We generated linked mutant alleles through recombination. All Robo1;2 homozygous pups examined quickly became cyanotic after birth, gasped for air, and died within minutes (Fig. 1A,B). Upon examination, we found that Robo1;2 mutant lungs, but not heterozygous control lungs, failed to inflate at birth (Fig. 1C–F), and quickly sank when placed in aqueous solution (data not shown). Immunostaining using an anti-Surfactant C antibody showed that the major surfactant-producing cell population, type II cells are present in normal numbers in the mutant (data not shown). While it remains possible that Robo genes are required within the lung for gas-exchange, we observed an extrinsic defect that may contribute to the failure of lung inflation: Robo1;2 mutants exhibit a striking fully penetrant mispositioning of the abdominal organs, primarily the stomach. Specifically, rather than being located on the left side of the abdominal cavity, the stomach of Robo1;2 mutants was located at the midline, and protruded through the esophageal hiatus into the thoracic cavity (Fig. 1G,H). The diaphragm of Robo1;2 mutants was also malformed (Fig. 1I,J). Because relatively little is known on how abdominal organ positioning is controlled, we sought to characterize the stomach protrusion phenotype further.

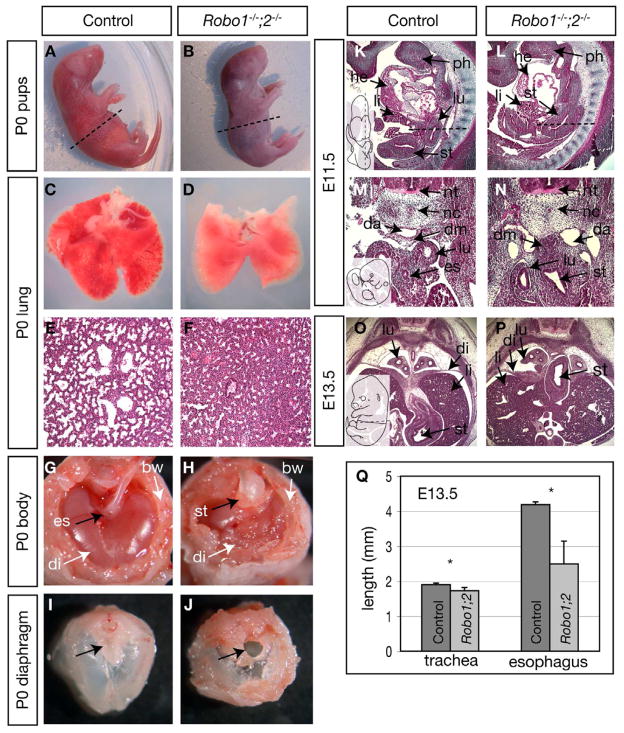

Figure 1. Gross defects in Robo1;2 mutants.

(A,B) Newborn pups. The mutant is cyanotic. (C–F) Wholemount (C,D) and hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) stained sections (E,F) of postnatal day 0 (P0) lungs showing that the mutant lung failed to inflate. (G–J) Anterior views of wholemount (G,H) or dissected diaphragms (I,J) from P0 pups cut at the approximate level indicated in A,B. Black arrows in H and J indicate the protrusion of the stomach through the diaphragm in the mutant. (K–P) H&E stained sagittal (K,L) and transverse (M–P) sections taken at the approximate planes indicated by dashed lines in the inset diagrams. The stomach remains between lung lobes in the mutant. (Q) Length of the trachea and esophagus of control and Robo1;2 embryos at E13.5 (trachea, Robo1;2: 1.7 ± 0.1 mm vs. control: 1.9 ± 0.04 mm, n = 4 each, p = 0.03; esophagus, Robo1;2: 2.48 ± 0.65 mm vs. control: 4.19 ± 0.07 mm, n = 4 each, p = 0.01). Data are presented as mean ± S.D. * denotes p ≤ 0.05. Abbreviations: bw=body wall, da=dorsal aorta, di=diaphragm, dm=dorsal mesentery, es=esophagus, he=heart, li=liver, lu=lung, nc=notochord, nt=neural tube, ph=pharyngeal arch, st=stomach.

We found that mispositioning of the stomach was already apparent at E11.5 prior to diaphragm formation. In control embryos the stomach was rotated to the left of the midline and shifted posterior to the lung lobes (Fig. 1K,M). In Robo1;2 embryos, however, the stomach remained anterior and was located at the midline between the lung lobes (Fig. 1L,N). Other left-right asymmetric properties such as heart, gut looping and lung lobe number were normal, suggesting that the midline placement of the stomach in Robo1;2 embryos is not due to a general left-right determination defect. Accompanying the stomach position phenotype, the dorsal aortae did not fuse in the mutant and remained separated by a thick band of mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1N). At E13.5, stomach mispositioning was more prominent as it interrupts the newly formed diaphragm (Fig. 1O,P). We found that the esophagus of Robo1;2 embryos was significantly shorter than in control embryos, while the trachea of Robo1;2 embryos was only slightly shorter than control (Fig. 1Q, see legends for quantification, Fig. 4R,S). These data suggest that in the Robo1;2 mutants, organ positioning defects precede the diaphragm defect.

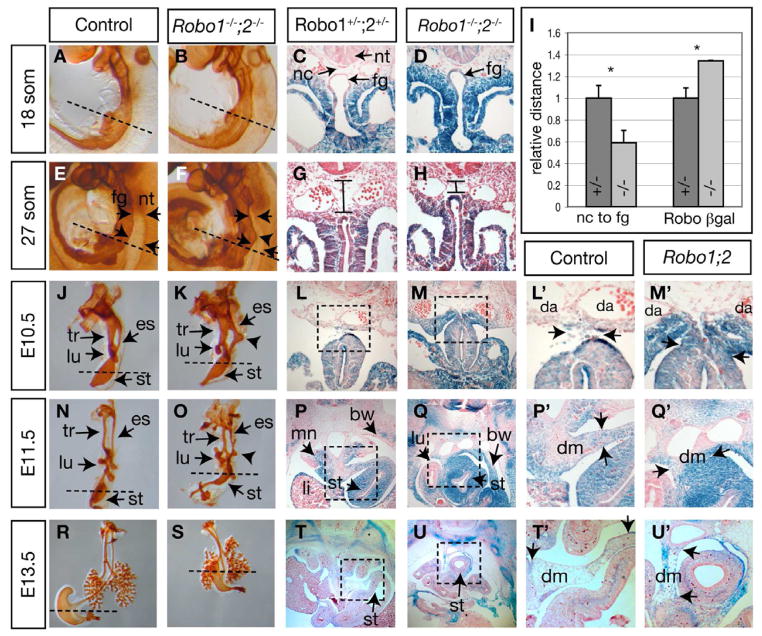

Figure 4. Robo1;2 mutants show delayed foregut movement away from body wall.

(A,B,E,F,J,K,N,O,R,S) Wholemount immunohistochemistry using anti-E-Cadherin antibody to outline foregut epithelium. (R,S) dorsal views; all others are lateral views. Arrows in E,F and lines in G,H indicate distances between gut endoderm and floorplate of neural tube. Arrowheads in F, K, O indicate the esophagus bulge seen in the mutant. Dashed lines in left two columns indicate approximate plane of sectioning for right columns.

(C,D,G,H,L,M,P,P′,Q,Q′,T,T′,U,U′) Transverse sections of X-gal-stained embryos expressing β-gal from the Robo1 and Robo2 loci. Boxed areas in L,M,P,Q,T,U are magnified in L′,M′,P′,Q′,T′,U′, respectively. Arrows in P′,Q′,T′,U′ denote the width (P′,Q′) or length (T′,U′) of the dorsal mesentery to demonstrate that the stomach is more closely attached to the body wall in the mutant. (I) Relative dorsal-ventral distance from notochord to foregut (relative ratio Robo1;2 mutants: 0.59 ± 0.11 vs. heterozygous controls: 1 ± 0.11, n = 3 each, p = 0.01), and relative lateral width of Robo β-gal expression domain in body wall (relative ratio Robo1;2 mutants: 1.34 ± 0.005 vs. heterozygous controls: 1 ± 0.09, n = 3 each, p = 0.02) at 27 somite stage. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. * denotes p ≤ 0.05. Additional abbreviations: mn=mesonephros, tr=trachea. See also Figure S1.

Robo and Slit genes are expressed in complementary patterns during early foregut morphogenesis

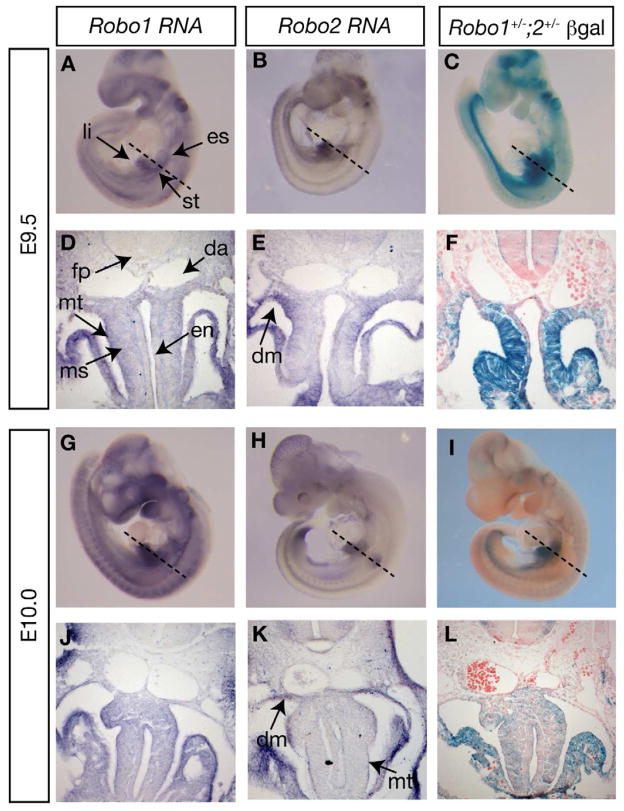

To determine the primary role of Slit/Robo signaling during early foregut morphogenesis, we sought first to examine the expression of Robo1-2, Slit1-3 using RNA in situ hybridization (Figs. 2, 3). The overall expression patterns we detected throughout the embryo were congruent with previously published results, confirming specificity of our probes (Brose et al., 1999; Yuan et al., 1999). At E9.5 (24 somites), Robo expression was detected in the mesothelium, mesenchyme and epithelium of the foregut, and in the dorsal mesentery connecting the foregut to the body wall (Fig. 2A,B,D,E). At E10.0, Robo1 was expressed in a similar pattern, while expression of Robo2 was primarily restricted to the mesothelium and the dorsal mesentery (Fig. 2G,H,J,K).

Figure 2. Expression of Robo genes during foregut morphogenesis.

(A,B,D,E,G,H,J,K) Robo1 and Robo2 expression assayed by RNA in situ hybridization. (C,F,I,L) X-gal-stained embryos expressing β-galactosidase (β-gal) from the Robo1 and Robo2 loci. Dashed lines in A–C and G–I indicate approximate plane of sectioning in D–F and J–L, respectively. Additional abbreviations: en=endoderm, fp=floor plate, ms=mesenchyme, mt=mesothelium.

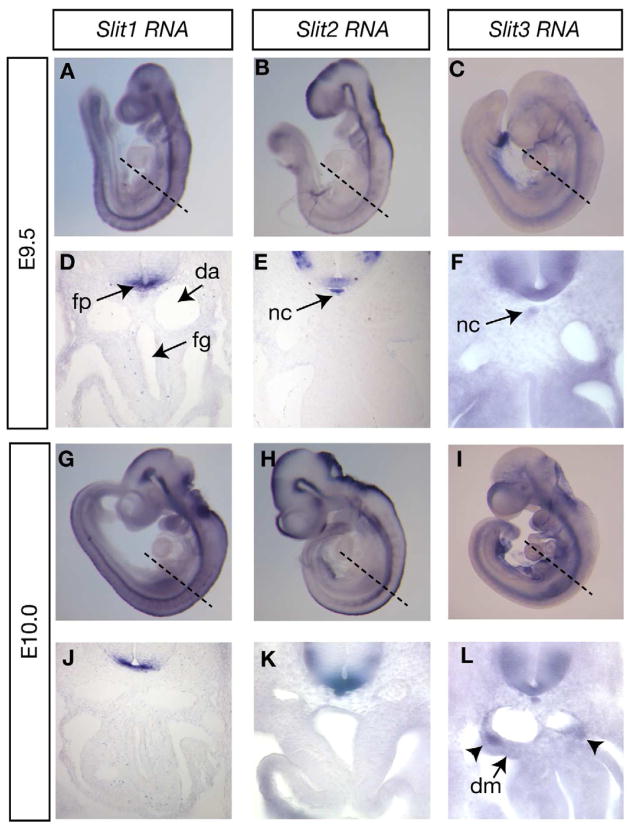

Figure 3. Expression of Slit genes during foregut morphogenesis.

(A–L) Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 expression assayed by RNA in situ hybridization. Dashed lines in A–C and G–I indicate approximate plane of sectioning in D–F and J–L, respectively. Arrowheads in L indicate Slit3 expression in the lateral dorsal mesentery. New abbreviations: fg=foregut.

To confirm the RNA in situ results, we took advantage of the lacZ reporter insertions present in both Robo1 and Robo2 mutant alleles (Grieshammer et al., 2004; Long et al., 2004). Sites of β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity closely corresponded to the RNA in situ pattern (Fig. 2C,F,I,L). By both detection methods, higher expression was observed in the liver and stomach region than the esophagus region (Fig. 2A–C). No expression was detected in the dorsal aortae.

In agreement with previous results, all three Slit genes were expressed in the floor plate of the neural tube at E9.5 and E10.0, while Slit2 and Slit3 were also expressed in the notochord at these stages (Fig. 3) (Brose et al., 1999). At E10.0, Slit3 was also high in two domains in the lateral mesentery, between the dorsal aortae and the body cavity (Fig. 3L, arrowheads). Combined together, Slit and Robo genes displayed largely complementary expression patterns, with Slit genes predominantly expressed in the neural tube, notochord, and lateral body wall mesentery, and Robo genes predominantly expressed in the mesothelium, mesenchyme and epithelium of the foregut as well as medial body wall mesentery (Fig. 2,3, Fig. 7J,K). We next addressed how disruption of this signaling framework would lead to the observed organ positioning defects.

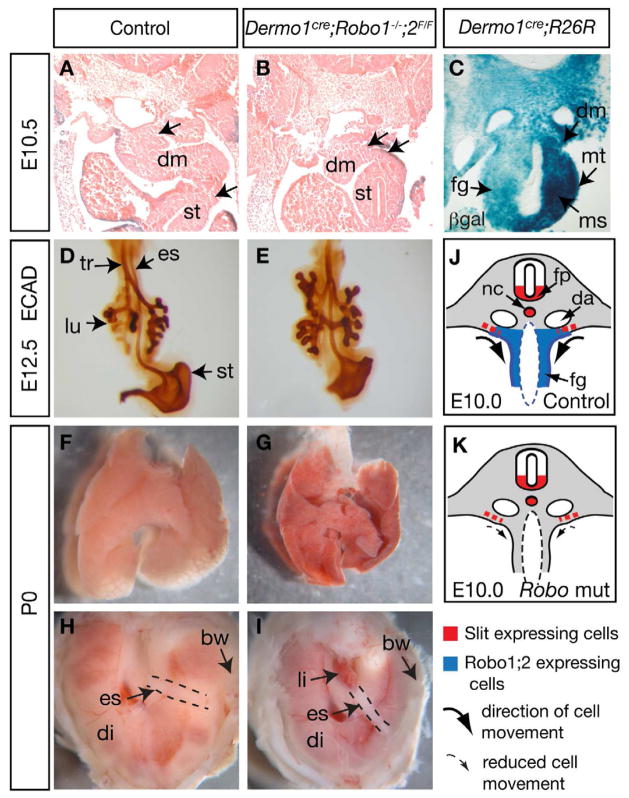

Figure 7. Conditional inactivation of Robo in mesenchyme and mesothelium leads to foregut morphogenesis and organ positioning defects.

(A–B) Transverse sections of E10.5 embryos at the posterior stomach level, with arrows indicating a shorter dorsal mesentery connecting the stomach and body wall in the Dermocre;Robo1;2 mutant. (C) Transverse section of X-gal stained E10.25 embryo indicating wide-spread Dermocre–induced reporter activity in mesenchyme/mesothelium. (D,E) E12.5 foregut stained with anti-E-Cadherin antibody to label the epithelium. (F,G) Mutant lungs failed to inflate at P0, in contrast to control. (H,I) Anterior surface view of the diaphragms. In this mutant sample, the liver protrudes through a larger opening in the diaphragm. In other Dermocre;Robo1;2 mutant samples, the stomach is seen to protrude, similar to that in the global mutants. (J,K) Diagrams of control and mutant transverse sections. Red and blue indicate Slit or Robo expression domains, respectively. Curved arrows indicate the postulated movement of ROBO expressing cells medially and ventrally away from Slit sources. In the mutant, this cell movement is reduced, resulting in prolonged close attachment of the foregut to body wall. See also Figure S3 and Table S1.

Robo1;2 mutants show defects in early foregut morphogenesis

To pinpoint the primary defect in the Robo1;2 mutant, we performed two parallel analyses on stage-matched embryos to comprehensively illustrate the tissue context. First, we stained whole embryos or foreguts with anti-Cadherin 1 (CDH1, E-cadherin) antibody to outline the developing gut epithelium (Fig. 4, left two columns). Second, we stained Robo1;2 heterozygous and homozygous mutant embryos for β-gal activity, and examined Robo cell distribution on transverse sections (Fig. 4, right four columns). Because the double homozygous mutant embryos carry four copies of lacZ transgene compared to two copies in double heterozygotes, β-gal activity is stronger in the mutant embryos. However, the intensity difference does not appear to interfere with detection of β-gal-positive Robo-expressing cells.

The combination of the two approaches allowed us to precisely determine the primary defect in the Robo1;2 mutants. At 18 somites (~E9.0), we observed no discernable difference in foregut morphology and tissue context between control and Robo1;2 embryos (Fig. 4A–D). At 27 somites (~E9.5), we detected the emergence of subtle differences (Fig. 4E–I). Specifically, in control embryos, the distance between the foregut endoderm and notochord was greater at 27 somites than at 18 somites (Fig. 4C,G). In Robo1;2 mutant embryos, however, the foregut endoderm remained near the notochord at 27 somites, similar to the morphology of 18 somite-stage embryos (Fig. 4D,H). This proximity was most apparent at, but not restricted to, the level of a dorsal bulge emerging in the foregut (arrowhead, Fig. 4F). The average notochord-foregut distance quantified at multiple representative levels along the anterior-posterior (A–P) axis of the foregut was statistically reduced in mutants compared to controls (Fig. 4I). Conversely, along the medial-lateral (M–L) axis where the foregut joins onto the body wall, the average medial-lateral distribution of β-gal+ Robo-expressing cells was statistically greater in mutant embryos than in heterozygous controls (Fig. 4G–I). These differences are magnified at E10.5 (~36 somites). In control embryos, the foregut was connected to the body wall by only a thin layer of dorsal mesentery (Fig. 4J,L,L′). The majority of β-gal+ cells were detected in mesenchyme/mesothelium surrounding the foregut, with a few still present in the body wall. In Robo1;2 mutants, however, the foregut remain closely fused to the body wall. A large number of β-gal+ cells remain in the wings of the body wall (Fig. 4K,M,M′). While most apparent at the stomach, similar reduced D–V distance between the neural tube and gut tube was observed in the esophagus and liver levels (Supplemental Fig. S1A–F). At E10.5, the previously observed bulge was consistently observed in the esophagus protruding dorsally towards the neural tube (Fig. 4K, Supplemental Fig. S1A–D).

At E11.5 in control embryos, the foregut in the stomach region had swung to the left and was loosely connected to the body wall by a long and thin band of mesentery (Fig. 4N,P,P′). However, in the equivalent region in Robo1;2 embryos, the foregut remained midline and closely connected to the body wall by a thick band of dorsal mesentery (Fig. 4O,Q,Q′). At E13.5 in control embryos, the diaphragm had formed, separating the stomach and the lung (Fig. 4R,T,T′ and Fig. 1O). However, in Robo1;2 mutants, the stomach was located between the lungs in the thoracic cavity while the diaphragm had formed around it (Fig. 4S,U,U′ and Fig. 1P). The dorsal mesentery connecting the stomach to the body wall remained shorter in Robo1;2 embryos compared to control (Fig. 4T′,U′ arrows). Collectively, these data show that the retarded ventral movement of the foregut tube away from the body wall and the accompanying reduced M–L restriction of Robo-expressing cells are the primary defects in Robo1;2 mutants, and both precede diaphragm malformation by ~3 days.

Previously it was shown that Slit3−/− mutants exhibit diaphragmatic hernia (Liu et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 2003). Herniation of the abdominal organs into the chest was attributed to defects in diaphragm formation. To address if Slit genes are also required for proper morphogenesis of the foregut earlier in development, we examined the histology of Slit mutants available to us. At E10.5, while Slit2−/− mutants showed only a mild defect, Slit3−/− mutants showed a clear shortening of the dorsal mesentery connecting the stomach to the body wall (Supplemental Fig. S1G–J). These data suggest that Slit ligands, like Robo receptors, are required in the early process of foregut morphogenesis away from the body wall.

Altered localization of adhesion molecules in Robo1;2 mutant foregut

We reasoned that the delayed foregut morphogenesis in Robo1;2 embryos could be due to a decrease in cell proliferation, a increase in cell death or a decrease in cell migration. To test these possibilities, we examined embryos at E10.0 shortly after the defect was first observed (Fig. 5A,B). We assayed for cell proliferation by labeling cells in S-phase with 5′-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) (Fig. 5C,D,G). In the region containing the dorsal mesentery as well as the foregut, rather than a decrease, we detected a slight, but statistically significant increase in the proportion of EdU+ cells in mutants relative to controls (Fig. 5G). Next we assayed for cell death using anti-cleaved-Caspase 3 antibody staining (Fig. 5E,F,H). We found very few cells labeled in either mutant or control and no statistically significant difference between the two genotypes (Fig. 5H). Together these data suggest that the delayed separation of the foregut from the body wall is not due to a decrease in cell proliferation or an increase in cell death.

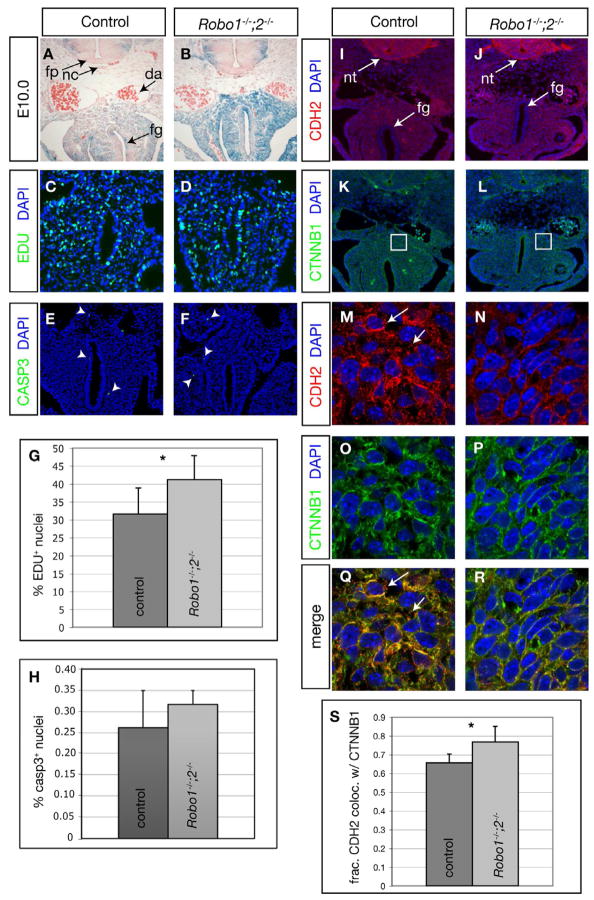

Figure 5. Disruption of Robo function alters adhesion molecule localization.

(A,B) Transverse sections of X-gal-stained embryos expressing lacZ from the Robo1 and Robo2 loci as a reference of Robo-expressing cell distribution. (C–F,I–R) Representative views of antibody-stained transverse sections of E10.0 embryos. Arrowheads in E,F indicate phosphorylated Caspase 3-positive cells undergoing apoptosis. (G) Quantification of percentage of EdU-positive proliferating cells in regions exemplified by C,D: Robo1;2 mutants 41.1 ± 7.6% vs. controls 33.9 ± 4.8%, n = 8 each, p = 0.05. (H) Quantification of percentage of Caspase3-positive cells in regions exemplified by E,F: Robo1;2 mutants 0.32 ± 0.03% vs. control 0.26 ± 0.09%, n = 4 each, p = 0.58. Boxed areas (K,L) are shown at increased magnification in M–R. Arrows in M,Q indicate CDH2+CTNNB1− puncta. (S) Fraction of CDH2 immunoreactivity that colocalizes with CTNNB1 immunoreactivity: Robo1;2 mutants 0.77 ± 0.084 vs. controls 0.66 ± 0.047, n = 7 each, p = 0.01. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. * denotes p ≤ 0.05.

Previous studies have demonstrated that activation of Slit-Robo signaling can interfere with cell adhesion by inhibiting the association of N-Cadherin (also termed Cadherin 2, CDH2) with β-catenin (CTNNB1), thereby disrupting the tethering of the actin cytoskeleton to the cell membrane (Rhee et al., 2002; Rhee et al., 2007). To address if this mechanism may mediate Slit-Robo control of foregut cell behavior, we examined the localization of CDH2 and CTNNB1 in control and mutant embryos (Fig. 5I–R). We found that, in agreement with previous reports, CDH2 was localized to the neural tube, mesenchyme and mesothelium of the foregut tube and body wall in control embryos (Hatta et al., 1987) (Fig. 5I). CDH2 was detected in similar groups of cells in Robo1;2 mutants (Fig. 5J). In closer examination of the mesenchyme of control embryos, CDH2 showed punctate localization at the membrane, consistent with the pattern observed in cells with activated Slit-Robo signaling (Fig. 5M,Q arrows) (Rhee et al., 2002). In Robo1;2 embryos, however, CDH2 was detected in a more uniform distribution along the cell membrane (Fig. 5N,R). CTNNB1 was detected in control and mutant embryos at similar subcellular patterns (Fig. 5K,L,O,P). Colocalization analyses revealed that a statistically significant larger proportion of CDH2 immunoreactivity overlapped with CTNNB1 immunoreactivity in Robo1;2 embryos relative to controls (Fig. 5Q–S). Collectively, these data suggest that cells expressing Robo proteins also express downstream mediators of Slit-Robo signaling, and that disruption of Slit-Robo signaling may interfere with the movement of foregut/body wall cells by altering the localization of adhesion machinery components.

Foregut cells are repelled by Slit protein

The complementary expression patterns of Slit and Robo genes, coupled with the primary defects in Robo1;2 mutants, suggest that Slit-Robo signaling may promote normal foregut morphogenesis by repelling Robo-expressing foregut cells away from the Slit-expressing neural tube and lateral body wall. To test this hypothesis directly, we assayed whether and how foregut cells would respond to Slit protein in vitro using the Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 6). We used stomach cells because the mispositioning of this organ is the most striking outcome of the morphogenesis defect and because it offers a rich source of cells. In the first test, we dissociated cells from E10.5 wild-type stomachs and seeded them in the top chamber on a culture insert, above either control COS-7 cells or SLIT2-producing COS-7 cells in the bottom chamber (Fig. 6A). After incubation, we scored the number of cells that had migrated to the bottom surface of the insert. We found that approximately 40% fewer stomach cells had migrated when SLIT2-producing cells were in the bottom chamber compared to control cells (Fig. 6C,D,G).

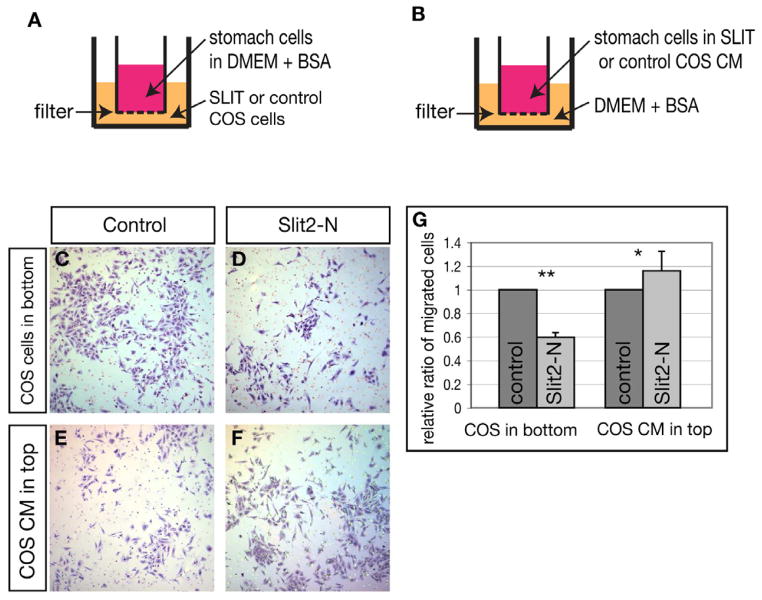

Figure 6. Foregut cells are repelled by Slit protein.

(A,B) Schematics of two Boyden chamber assays. In both, stomach cells are seeded into the upper chamber and assayed for the ability to migrate to and be retained at the fibronectin coated bottom surface of the filter. (C–F) Representative views of crystal-violet-stained stomach cells that migrated to the bottom of the filter. (G) Quantification of migrated stomach cells. Slit2 or control transfected COS cells in the bottom chambers, SLIT2 vs. control 0.60 ± 0.0.03, n = 6 each, p = 8 × 10−6. SLIT2 or control conditioned medium (CM) in the top chambers, SLIT2-CM vs. control-CM 1.18 ± 0.17, n = 6 each, p = 0.006. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. * denotes p ≤ 0.05, ** denotes p ≤ 0.005. See also Figure S2.

In the second test, we resuspended E10.5 wild-type stomach cells in control- or SLIT2-conditioned media (CM), and seeded them in the top chamber on a culture insert, above control media in the bottom chamber (Fig. 6B). After incubation, we found that approximately 18% more stomach cells had migrated to the bottom surface of the cell culture insert when SLIT2-CM was in the top chamber than control-CM (Fig. 6E–G). The results from these tests suggest that Robo-expressing wild-type cells from the foregut region are repelled by Slit signal.

Finally, to determine if foregut cells from Robo1;2 mutants are compromised in their migratory behavior in response to a source of Slit protein, we dissociated stomach cells from E10.5 Robo1;2 mutant or control embryos and seeded the same number of cells in SLIT2-CM in the top chamber above control media in the bottom chamber (Fig. 6B). After incubation, we found that approximately 45% fewer cells from Robo1;2 embryos migrated compared to that from control embryos (Supplemental Fig. S2). The combined data from the Boyden chamber assays demonstrate that foregut cells are repelled by Slit protein in vitro in a Robo-dependent manner. These findings, together with Slit-Robo gene expression data, suggest that disruption of a similar process in vivo may contribute to the delayed separation of the foregut from the body wall observed in Robo1;2 mutants.

Robo function is required in the mesenchyme/mesothelium for organ positioning

Robo genes are expressed in the foregut in both the endoderm-derived epithelium and the mesoderm-derived mesenchyme/mesothelium. It is unclear whether Robo function is required in both or just one of these cell lineages for foregut morphogenesis. In addition, it remains unclear whether Robo function is required within the lung or extrinsic to the lung for its inflation at birth. To distinguish among these possibilities, we obtained a Robo2 floxed allele, Robo2fl (Lu et al., 2007) and linked it to Robo1− by recombination. We note that Robo1−/− single mutants show no detectable foregut phenotype in our study. By combining the linked alleles with distinct cre lines, we were able to inactivate the collective function of Robo1;2 in tissues of interest (Supplemental Table S1).

We used Shhcre to inactivate Robo function in the endoderm-derived epithelium and Dermo1cre to inactivate Robo function in the mesoderm-derived mesenchyme and mesothelium (Harris et al., 2006; Harris-Johnson et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2003). Shhcre; Robo1;2 mutants (n=5) showed normal organ positioning, diaphragm formation and lung inflation at birth (Supplemental Fig. S3A–D). In contrast, Dermo1cre; Robo1;2 mutants (n=9) showed a closer attachment of foregut to the body wall, shorter esophagus, protrusion of the abdominal organs into the chest (either stomach or liver is observed in this conditional mutant), aberrant opening of the diaphragm and inability to inflate the lung at birth (Fig. 7 and data not shown). These defects are similar to those observed in Robo1;2 global loss-of-function mutants, albeit less severe, likely due to later Robo inactivation by Dermo1cre. Dermo1cre is active in the mesenchyme/mesothelium of many organs, as well as in the dorsal mesentery (Fig. 7C) (Yu et al., 2003). To address if Robo function is specifically required in the lung mesenchyme, we generated Tbx4cre; Robo1;2 mutants (Supplemental Fig. S3). While Tbx4cre is also active in the hindlimb, external genitalia and a few other posterior mesoderm derivatives, in the context of the foregut, its activity is restricted to the lung mesenchyme. There is no activity in the dorsal mesentery or the diaphragm (Naiche et al., 2011). Tbx4cre; Robo1;2 mutants showed normal lung and diaphragm morphology and lung inflation at birth (n=6, Supplemental Fig. S3E,F,H,I). We confirmed Robo inactivation in the lung by performing quantitative RT-PCR for Robo2 (Supplemental Fig. S3G). Taken together, our data from tissue-specific inactivation show that Robo genes are required in the mesenchyme/mesothelium lineages outside of the lung to control organ positioning, proper closure of the diaphragm and lung inflation at birth.

Discussion

In this study, we report that Robo1;2 mutant mice die at birth with protrusion of the abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity, resembling CDH cases in humans (Ackerman and Greer, 2007; Holder et al., 2007; Pober, 2008). In this mouse genetic model of CDH, we traced the morphological defects to a surprisingly early foregut morphogenesis event that is rarely considered. Our findings illustrate that a thorough understanding of the origin of defects using animal models can provide important insights into the etiology of human congenital anomalies.

The primary Robo1;2 mutant phenotype led us to focus on the relationship between the foregut and surrounding tissues. After gastrulation, the foregut endoderm is in close apposition to the neural tube and notochord (Li et al., 2007; Que et al., 2006; Teillet et al., 1998). As we highlight here, the distance between the endoderm and the notochord increases over time (Fig. 4). The observed cell proliferation in this region may contributes to this increase (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, our evidence suggests that there is likely a progressive restriction of dorsal body wall cells, as marked by their Robo-expression, along the M–L axis, where they are eventually found ventrally surrounding the foregut tube (Fig. 4C,G,L). Concurrently, the two dorsal aortae that reside just above the body wall mesenchyme converge and fuse at the midline. These observations suggest that a coordinated medial- and ventral- directional cell movement may contribute to the further increase in distance between the foregut endoderm and notochord (Fig. 7J,K). As a result, the foregut becomes connected to the body wall only through a thin dorsal mesentery. This loose association would allow the foregut endoderm to elongate freely in relationship to the body wall tissues.

Our finding that the foregut in Robo1;2 mutants remains closely associated with the body wall indicate that foregut-body wall separation is genetically controlled. Although we have used the stomach as a primary example, this morphogenesis defect is observed at multiple A–P levels along the foregut in the Robo1;2 mutant (Fig. 4, Supplemental Fig. S1). All three Slit genes are expressed in the vicinity of the foregut. Additionally, Slit3 mutants show closer foregut to body wall distance compared to controls (Supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, although ligand-independent homophilic interactions among Robo receptors can also modulate cell behavior (Hivert et al., 2002; Jaworski et al., 2010), our data suggest that Robo function in foregut morphogenesis is likely Slit-dependent.

Several lines of evidence lead us to postulate that Slit-Robo signaling controls foregut morphogenesis via cell repulsion. First, we found that Slit/Robo genes are expressed in largely complementary patterns. In a normal embryo, the Robo-expressing foregut moves away from Slit sources. Second, we did not observe a reduction in cell proliferation or increase in cell death in the dorsal mesentery and foregut of Robo1;2 mutants, suggesting that these are not likely the cause of the reduced foregut-body wall distance. Third, we observed a wider spread of Robo-expressing body wall cells and that the dorsal aortae remain apart in Robo1;2 mutants, suggesting an impairment of concerted medial movement away from the lateral Slit source. Fourth, we showed that wild-type Robo-expressing foregut cells are repelled by Slit protein in vitro and that this behavior is impaired in cells from Robo1;2 mutants (Fig. 6, Supplemental Fig. S2). Together, these data are consistent with the phenotypes of Robo1;2 embryos in vivo, and with the fact that Slit is often, though not always, a repulsive cue for Robo-expressing cells (Lundstrom et al., 2004; Ma and Tessier-Lavigne, 2007; Rhee et al., 2002; Rhee et al., 2007; Shiau and Bronner-Fraser, 2009). We postulate that the coordinated repulsion of cells in both the dorsal mesentery as well as the foregut together facilitate foregut ventral movement away from the neural tube.

While Robo genes are expressed in both the endoderm-derived epithelium and mesoderm-derived mesenchyme/mesothelium, data from conditional knockout experiments demonstrate that they are required in the mesenchyme/mesothelium for foregut morphogenesis. At present, we cannot distinguish Slit-Robo function in the mesenchyme versus mesothelium. A recent report shows that at the level of the intestine, mesothelium progenitors arise intrinsic to the gut tube rather than ingressing in as a sheet over the splanchnic mesenchyme (Winters 2012). If this can be generalized to the foregut organs, it is plausible that the mesenchymal and mesothelial cells would coordinate their movement and respond similarly to Slit-Robo signaling.

We speculate that the prolonged close association of the foregut to the body wall may prevent normal foregut elongation and result in retention of the stomach in the chest. Meanwhile, it is important to note that our data do not rule out the possibility that Robo genes may play other essential roles at later steps in the formation of foregut-derived organs. For example, while shortened esophagus is not a primary defect because it is observed later than the reduced foregut separation (Fig. 4E,F,N,O), it could also result from disruption of a direct role of Robo in esophagus elongation. However, it would be difficult to explain a priori why the reduced growth is restricted to the esophagus, but not observed in a more posterior region of the foregut (e.g. stomach), where Robo expression appears to be higher than in the esophagus region (Fig. 2A–C). It is interesting to note that prior to the shortening, the first defect observed within the esophagus is an aberrant bulge towards the dorsal body wall (Fig. 4K), suggesting that a morphogenesis defect may be a trigger for the shortening. We considered the possibility that the bulge arose from a disruption of planar cell polarity. However, an examination of planar cell polarity mutants such as Wnt5a−/− embryos failed to reveal a similar defect in the foregut (data not shown). Since the bulge always points towards the dorsal body wall, it is plausible that it may form as a consequence of increased foregut tethering to the body wall.

A critical late phenotype in Robo1;2 mutant mice is the failure of lung inflation at birth. While Robo and Slit genes are expressed in the developing lung (Anselmo et al., 2003; Greenberg et al., 2004), our data suggest that failed inflation is likely secondary to the requirement for Robo outside of the lung. Lungs inflated normally in both Tbx4cre; Robo1;2 and Shhcre; Robo1;2 where Robo genes are inactivated in lung mesenchyme/mesothelium or epithelium, respectively. This is in contrast to Dermo1cre; Robo1;2 mutants where failure of lung inflation is preceded by organ misplacement. Thus we postulate that in Robo1;2 global knockouts, the lungs failed to inflate due to either mechanical compression of the lung by abdominal content in the chest, or ineffective contraction of the malformed diaphragm.

The malformation of the diaphragm in the Robo mutants could be secondary to herniation of the abdominal organs into the chest, or it could be an independent defect due to loss of Robo function in the diaphragm. It is worth noting that while separated by 3 days (E10.5-E13.5), the earlier event of foregut morphogenesis shares striking similarities with the later event of diaphragm formation. Central to both of these events is the concerted migration of mesenchymal/mesothelial cells. In this study, we postulate that medial and ventral migration of dorsal body wall mesenchyme/mesothelial cells is important for the separation of the foregut from the body wall. Previously, it has been proposed that medial migration of peritoneal buds is important for fusion of multiple mesenchymal/mesothelial populations to form the diaphragm (Yuan et al., 2003). In light of these similarities, it is plausible that Slit-Robo signaling may play a recurring role in the morphogenesis of multiple mesoderm-derived tissues during development.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a relatively common birth defect, occurring in approximately 1/3000 live births and is associated with a high rate of neonatal lethality (Ackerman and Greer, 2007; Holder et al., 2007; Pober, 2008). It is generally thought to arise due to malformation of the diaphragm. Here we show that in Robo1;2 mutants, a mouse model of CDH, the foregut morphogenesis defect precedes the diaphragm defects. Whether the foregut defect could serve as a general underlying cause of human CDH remains to be seen. However, it is worth noting that a deletion of the chromosomal region spanning the linked ROBO1 and ROBO2 (del(3)(p12p21)) has been reported in human CDH (Holder et al., 2007; Pfeiffer et al., 1998).

Experimental Procedures

Generation of mutant mice

Embryos were dissected from time-mated mice, counting noon on the day when the vaginal plug was found as embryonic day (E) 0.5. Robo1tm1Matl (Robo1), Robo2tm1Mrt (Robo2) and Robo2 (Robo2fl) mutant alleles and Dermo1cre allele have been previously described (Grieshammer et al., 2004; Long et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2003) (Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Somite-matched littermates were used as controls.

Embryos were fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C, then either dehydrated in methanol and stored, equilibrated in 30% sucrose and embedded either in OCT or paraffin for sectioning. Wholemount in situ hybridization (WMISH) was performed as previously described (Abler et al., 2011) (Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Probes have been described previously (Brose et al., 1999).

β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining and histology

β-gal activity was assayed by a standard protocol. Embryos at stages E10.5 and younger were fixed and stained prior to being processed for paraffin embedding. Sections were cut at 7 μm and counterstained with 1% eosin. Embryos at stages later than E10.5 were fixed, sectioned at 500 μm thickness with a vibratome, then stained overnight before being dehydrated and processed for paraffin embedding and sectioning.

Immunofluorescent and immunohistochemical staining

For immunofluorescence, frozen sections (10μm) were stained using a standard protocol, and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). For immunohistochemistry, antigen detection was performed with DAB kit (Vector Laboratories). Colocalization quantification was performed on 1–2 sections each from 5 control and 5 mutant embryos using JACoP in ImageJ software (Bolte and Cordelieres, 2006). Identical threshold settings were used for all images in the analyses, and overlap compared using Student’s t-test. Results are reported as mean ± S.D., and were considered statistically significant if p≤ 0.05.

Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-E-cadherin (Cell Signaling, 1:200), rabbit anti-β-catenin (Invitrogen, 1:200), mouse anti-Cadherin 2 (Invitrogen, 1:200), and rabbit anti-Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, 1:200). Secondary antibodies used were Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse, FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:400 dilution).

Cell proliferation assay

Pregnant females received an intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg EdU (Sigma) thirty minutes prior to sacrifice. Samples were frozen in OCT and cryosectioned. EdU detection was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). The percentage EdU+ nuclei between control (3 embryos, n = 8 sections) and Robo1;2 (3 embryos, n = 8 sections) was calculated using ImageJ and compared using Student’s t-test. Results are reported as mean ± S.D., and were considered statistically significant if p ≤ 0.05.

Boyden chamber Cell migration assays

Stomachs from 16 wild-type E10.5 embryos were dissected, and incubated for 75 minutes at 37°C in 1 mL of DMEM/F12-K containing 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) and 1 mg/mL collagenase/dispase (Roche) to dissociate the cells. For the first set of experiments (Fig. 6A), stomach cells were resuspended in DMEM + 0.1% BSA at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, and 200 μL aliquots were seeded into the top chamber of 8 μm pore-size cell culture inserts (BD Biosciences) coated with fibronectin (Sigma). Inserts were placed into a 24-well plate above the transfected COS-7 cells (n = 6 inserts per each treatment). For the second set of experiments, stomach cells were washed and resuspended in conditioned media (CM) from control or SLIT2-N-transfected COS cells and seeded into chambers as described above. These chambers were placed into wells of a 24-well plate containing 700 μL DMEM + 0.1% BSA. For SLIT2-conditioned media (CM), COS-7 cells were transfected with plasmid encoding the N-terminal domain of SLIT2 (SLIT2-N) (Nguyen Ba-Charvet et al., 2001; Wang et al., 1999) or empty vector control using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol 48 hours prior to the experiment.

For each of the Boyden chamber assay, after 9-hours incubation, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Unmigrated cells were removed from the top surface of the cell culture insert. The membrane was then mounted in Permount (Fisher). Four non-overlapping 10x fields of view were photographed of each membrane, and the number of migrated cells counted using ImageJ. Results are reported as mean relative ratio of migrated cells ± S.E.M., and were considered statistically significant if p≤ 0.05. Each experiment was performed twice.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Robo1;2 mutants show defects reminiscent of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH).

The primary defect in Robo mutants is delayed foregut separation from the body wall.

Loss of Robo impedes repulsion of foregut cells away from Slit source.

The foregut separation defect precedes and may contribute to CDH-like pathologies.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Sun and Ikeda labs for helpful discussions and insights, Amber Lashua and Julie Harvey for expert technical assistance. We thank Drs. David Ornitz, Brian Harfe and Vasi Sundaresan for sharing mouse strains. E.D. was supported by NSF graduate research fellowship 2008044659. This work was supported by a Wright Foundation research grant and NINDS NS062047 (to L.M), and a Burroughs-Wellcome career award #1002361, American Heart grant #0950041G, March of Dimes grant 6-FY10-339 and NHLBI HL113870 (to X.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abler LL, Mehta V, Keil KP, Joshi PS, Flucus CL, Hardin HA, Schmitz CT, Vezina CM. A High Throughput in Situ Hybridization Method to Characterize mRNA Expression Patterns in the Fetal Mouse Lower Urogenital Tract. J Vis Exp. 2011;54:2912. doi: 10.3791/2912. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman KG, Greer JJ. Development of the Diaphragm and Genetic Mouse Models of Diaphragmatic Defects. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145C:109–116. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman KG, Herron BJ, Vargas SO, Huang H, Tevosian SG, Kochilas L, Rao C, Pober BR, Babiuk RP, Epstein JA, et al. Fog2 is Required for Normal Diaphragm and Lung Development in Mice and Humans. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:58–65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmo MA, Dalvin S, Prodhan P, Komatsuzaki K, Aidlen JT, Schnitzer JJ, Wu JY, Kinane TB. Slit and Robo: Expression Patterns in Lung Development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S, Cordelieres FP. A Guided Tour into Subcellular Colocalization Analysis in Light Microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose K, Bland KS, Wang KH, Arnott D, Henzel W, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kidd T. Slit Proteins Bind Robo Receptors and have an Evolutionarily Conserved Role in Repulsive Axon Guidance. Cell. 1999;96:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellard ME, Rao Y, Bronner-Fraser M. Dual Function of Slit2 in Repulsion and Enhanced Migration of Trunk, but Not Vagal, Neural Crest Cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domyan ET, Sun X. Patterning and Plasticity in Development of the Respiratory Lineage. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:477–485. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Steneberg P, Fallileeva L, Xylourgidis N, Samakovlis C. Attractive and Repulsive Functions of Slit are Mediated by Different Receptors in the Drosophila Trachea. Development. 2002;129:4941–4951. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JM, Thompson FY, Brooks SK, Shannon JM, Akeson AL. Slit and Robo Expression in the Developing Mouse Lung. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:350–360. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U, Le M, Plump AS, Wang F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Martin GR. SLIT2-Mediated ROBO2 Signaling Restricts Kidney Induction to a Single Site. Dev Cell. 2004;6:709–717. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, Scherz PJ, Nissim S, Tian H, McMahon AP, Tabin CJ. Evidence for an Expansion-based Temporal Shh Gradient in Specifying Vertebrate Digit Identities. Cell. 2004;188:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KS, Zhang Z, McManus MT, Harfe BD, Sun X. Dicer Function is Essential for Lung Epithelium Morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510839103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Johnson KS, Domyan ET, Vezina CM, Sun X. -catenin Promotes Respiratory Progenitor Identity in Mouse Foregut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16287–16292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902274106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta K, Takagi S, Fujisawa H, Takeichi M. Spatial and Temporal Expression Pattern of N-Cadherin Cell Adhesion Molecules Correlated with Morphogenetic Processes of Chicken Embryos. Dev Biol. 1987;120:215–227. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hivert B, Liu Z, Chuang CY, Doherty P, Sundaresan V. Robo1 and Robo2 are Homophilic Binding Molecules that Promote Axonal Growth. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:534–545. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder AM, Klaassens M, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Lee B, Scott DA. Genetic Factors in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:825–845. doi: 10.1086/513442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski A, Long H, Tessier-Lavigne M. Collaborative and Specialized Functions of Robo1 and Robo2 in Spinal Commissural Axon Guidance. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9445–9453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6290-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the Midline Repellent for the Robo Receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96:785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Brose K, Mitchell KJ, Fetter RD, Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS, Tear G. Roundabout Controls Axon Crossing of the CNS Midline and Defines a Novel Subfamily of Evolutionarily Conserved Guidance Receptors. Cell. 1998;92:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Litingtung Y, Ten Dijke P, Chiang C. Aberrant Bmp Signaling and Notochord Delamination in the Pathogenesis of Esophageal Atresia. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:746–754. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang L, Wang D, Shen H, Jiang M, Mei P, Hayden PS, Sedor JR, Hu H. Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia, Kidney Agenesis and Cardiac Defects Associated with Slit3-Deficiency in Mice. Mech Dev. 2003;120:1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H, Sabatier C, Ma L, Plump A, Yuan W, Ornitz DM, Tamada A, Murakami F, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Conserved Roles for Slit and Robo Proteins in Midline Commissural Axon Guidance. Neuron. 2004;42:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, van Eerde AM, Fan X, Quintero-Rivera F, Kulkarni S, Ferguson H, Kim H, Fan Y, Xi Q, Li Q, et al. Disruption of ROBO2 is Associated with Urinary Tract Anomalies and Confers Risk of Vesicoureteral Reflux. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:616–632. doi: 10.1086/512735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom A, Gallio M, Englund C, Steneberg P, Hemphala J, Aspenstrom P, Keleman K, Falileeva L, Dickson BJ, Samakovlis C. Vilse, a Conserved Rac/Cdc42 GAP Mediating Robo Repulsion in Tracheal Cells and Axons. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2161–2171. doi: 10.1101/gad.310204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Tessier-Lavigne M. Dual Branch-Promoting and Branch-Repelling Actions of Slit/Robo Signaling on Peripheral and Central Branches of Developing Sensory Axons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6843–6851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1479-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias H, Moran A, Samara Y, Moreno M, Compton JE, Harburg G, Strickland P, Hinck L. SLIT/ROBO1 Signaling Suppresses Mammary Branching Morphogenesis by Limiting Basal Cell Number. Dev Cell. 2011;20:827–840. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiche LA, Arora R, Kania A, Lewandoski M, Papaioannou VE. Identity and Fate of Tbx4-Expressing Cells Reveal Developmental Cell Fate Decision in the Allantois, Limb, and External Genitalia. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:2290–2300. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Ba-Charvet KT, Brose K, Ma L, Wang KH, Marillat V, Sotelo C, Tessier-Lavigne M, Chedotal A. Diversity and Specificity of Actions of Slit2 Proteolytic Fragments in Axon Guidance. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4281–4289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04281.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer RA, Rauch A, Ulmer R, Beinder E, Trautmann U. Interstitial Deletion Del(3)(p12p21) in a Malformed Child Subsequent to Paternal Paracentric Insertion (Or Intraarm Shift) 46, XY, Ins(3)(p24.1p12.1p21.31) Ann Genet. 1998;41:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pober BR. Genetic Aspects of Human Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Clin Genet. 2008;74:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pober BR, Russell MK, Ackerman KG. Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Overview. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Que J, Choi M, Ziel JW, Klingensmith J, Hogan BL. Morphogenesis of the Trachea and Esophagus: Current Players and New Roles for Noggin and Bmps. Differentiation. 2006;74:422–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee J, Buchan T, Zukerberg L, Lilien J, Balsamo J. Cables Links Robo-Bound Abl Kinase to N-Cadherin-Bound Beta-Catenin to Mediate Slit-Induced Modulation of Adhesion and Transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:883–892. doi: 10.1038/ncb1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee J, Mahfooz NS, Arregui C, Lilien J, Balsamo J, VanBerkum MF. Activation of the Repulsive Receptor Roundabout Inhibits N-Cadherin-Mediated Cell Adhesion. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:798–805. doi: 10.1038/ncb858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg JM, Hartley DA, Walther Z, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Slit: An EGF-Homologous Locus of D. Melanogaster Involved in the Development of the Embryonic Central Nervous System. Cell. 1988;55:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau CE, Bronner-Fraser M. N-Cadherin Acts in Concert with Slit1-Robo2 Signaling in Regulating Aggregation of Placode-Derived Cranial Sensory Neurons. Development. 2009;136:4155–4164. doi: 10.1242/dev.034355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teillet MA, Lapointe F, Le Douarin NM. The Relationships between Notochord and Floor Plate in Vertebrate Development Revisited. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11733–11738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Xiao Y, Ding BB, Zhang N, Yuan X, Gui L, Qian KX, Duan S, Chen Z, Rao Y, Geng JG. Induction of Tumor Angiogenesis by Slit-Robo Signaling and Inhibition of Cancer Growth by Blocking Robo Activity. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KH, Brose K, Arnott D, Kidd T, Goodman CS, Henzel W, Tessier-Lavigne M. Biochemical Purification of a Mammalian Slit Protein as a Positive Regulator of Sensory Axon Elongation and Branching. Cell. 1999;96:771–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye BQ, Geng ZH, Ma L, Geng JG. Slit2 Regulates Attractive Eosinophil and Repulsive Neutrophil Chemotaxis through Differential srGAP1 Expression during Lung Inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;185:6294–6305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ypsilanti AR, Zagar Y, Chedotal A. Moving Away from the Midline: New Developments for Slit and Robo. Development. 2010;137:1939–1952. doi: 10.1242/dev.044511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, Towler DA, Ornitz DM. Conditional Inactivation of FGF Receptor 2 Reveals and Essential Role for FGF Signaling in the Regulation of Osteoblast Function and Bone Growth. Development. 2003;130:3063–3074. doi: 10.1242/dev.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Rao Y, Babiuk RP, Greer JJ, Wu JY, Ornitz DM. A Genetic Model for a Central (Septum Transversum) Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia in Mice Lacking Slit3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5217–5222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730709100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Zhou L, Chen JH, Wu JY, Rao Y, Ornitz DM. The Mouse SLIT Family: Secreted Ligands for ROBO Expressed in Patterns that Suggest a Role in Morphogenesis and Axon Guidance. Dev Biol. 1999;212:290–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.