Abstract

Objective

Mast cells (MC) reside in the mucosa of the digestive tract as the first line against bacteria and toxins. Clinical evidence has implied that the infiltration of mast cells in colorectal cancers is related to malignant phenotypes and a poor prognosis. This study compared the role of mast cells in adjacent normal colon mucosa and in the invasive margin during the progression of colon cancer.

Methods

Specimens were obtained from 39 patients with colon adenomas and 155 patients with colon cancers treated at the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center between January 1999 and July 2004. The density of mast cells was scored by an immunohistochemical assay. The pattern of mast cell distribution and its relationship with clinicopathologic parameters and 5-year survival were analyzed.

Results

The majority of mast cells were located in the adjacent normal colon mucosa, followed by the invasive margin and least in the cancer stroma. Mast cell count in adjacent normal colon mucosa (MCCadjacent) was associated with pathologic classification, distant metastases and hepatic metastases, although it was not a prognostic factor. In contrast, mast cell count in the invasive margin (MCCinvasive) was associated with neither the clinicopathlogic parameters nor overall survival.

Conclusion

Mast cells in the adjacent normal colon mucosa were related to the progression of colon cancer, suggesting that mast cells might modulate tumor progression via a long-distance mechanism.

Key words: Mast cell, Colon cancer, Mucosa, Invasive margin, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

In addition to genetic alterations of cancer cells, the infiltration of immune cells, such as dendritic cells, T cells, macrophages, and mast cells (MC) is believed to be involved in tumor progression[1-3]. For example, mast cells might impact tumor progression by induction of angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and immune cell recruitment[4]. Although the experimental data support the notion that infiltration of mast cells in tumor tissue plays an important role in tumor progression, the relevant clinical evidence is complicated; the infiltrated mast cells might positively, negatively, or irrespectively impact tumor progression[5-7]. With respect to colorectal cancers, the relationship between the infiltration of mast cells and tumor progression is also controversial[8-17]. As the function of mast cells may be related to its phenotype and location in cancer tissue[18], the current study examined the role of mast cells in the adjacent normal colon mucosa and in the invasive margin during the progression of colon cancer.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Paraffin-embedded specimens, including tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues, were obtained from 39 patients with pathologic evaluation-confirmed colon adenomas and 155 patients with colon cancers who underwent radical resection or biopsy between January 1999 and July 2004 at the SunYat-senUniversityCancerCenter in Guangzhou, China (Table 1). The TNM classification system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (edition 6) was used for clinical staging, and the World Health Organization classification of tumors (2000 version) was used for histological tumor grading. Patients did not receive chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery.

Table 1. The count of mast cells in colon adenomas and colon cancers.

| Tumor | n | MCCadjacent(median±interquartile range) | MCCinvasive(median±interquartile range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoma | 39 | 7.20±2.72 | --- |

| Colon Cancer Stage I | 38 | 6.60±3.31 | 3.80±2.36 |

| Colon Cancer Stage II | 38 | 7.70±3.48 | 4.80±2.47 |

| Colon Cancer Stage III | 38 | 7.70±3.17 | 3.80±2.73 |

| Colon Cancer Stage IV | 41 | 9.00±2.83 | 3.70±1.89 |

| P | a0.003** | 0.092** |

**Kruskal-Wallis test. aP<0.05, statistically significant.

Follow-up

Follow-up was provided to stage I–IV colon cancer patients. Patients were observed on an every-3-month basis during the 1st year, once every 6 months in the 2nd year, and by telephone or mail communication once every year thereafter, for a total of 5 years. Patients received adjuvant or palliative 5-FU-based chemotherapy according to the NCCN guidelines. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to death or was censored at the last known alive data.

Immunohistochemical Assay

Tissue sections (5 μm thickness) were cut, dried, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in graded alcohol and xylene before antigen retrieval by pressure cooker treatment in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 3 min. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide incubation. Mouse anti-human mast cell tryptase monoclonal antibody (1:160,000 dilution, Serotec, Oxford, UK), mouse anti-human mast cellchymase monoclonal antibody (1:8,000 dilution, Serotec, Oxford, UK), and mouse anti-human CD31 monoclonal antibody (working solution, catalog number: ZM-0044, ZhongshanGoldenbridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) were used. Immunostaining was performed using the EnVision+ Dual Link Kit (DakoCytomation, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The development was performed with a substrate-chromogen solution (3,3’- diaminobenzidinedihydrochloride [DAB]) for 3-5 min. Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted in non-aqueous mounting medium.

Mast Cell Evaluation

The mast cell count in the invasive margin (MCCinvasive) was defined as the number of tryptase-positive mast cells localized in the invasive margin of the colon cancer, as tryptase expression occurs universally in mast cells. The stained sections were first screened under a low power objective (100×) to identify the areas with the highest number of mast cells in the invasive margin. The MCCinvasive was then recorded under 400× magnification [1 mm2 per high power field (HP)] in 5 fields of vision with an ocular micrometer. The number of mast cells in every field was expressed as MC/HP, and for each case, the mean MCCinvasive was noted. The mean MCCinvasive= the total number of mast cells in the five fields divided by five. The mast cell count in adjacent normal colon mucosa (MCCadjacent) was also evaluated in five consecutive fields, similarly to MCCinvasive. The mast cell count (MCC) in each section was scored separately by two independent observers with no prior knowledge of clinicopathologic parameters. The inter-observer agreement for the MCC was 81%. Disagreements were re-evaluated until a consensus was reached.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The descriptive statistical tests, including the mean, standard deviation, and median were calculated according to the standard methods. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilks’ W-test were used to analyze the normality of the distribution. The relationship between the various clinicopathologic characteristics and the MCC parameters were compared and analyzed using Chi-square tests, likelihood ratio, and linear-by-linear association, as appropriate. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to evaluate the significance of the differences of the mean ranks. Cumulative survival curves were drawn by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference between the curves was analyzed by the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses were based on the Cox proportional hazards regression model. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Phenotypes and Distribution of Mast Cells

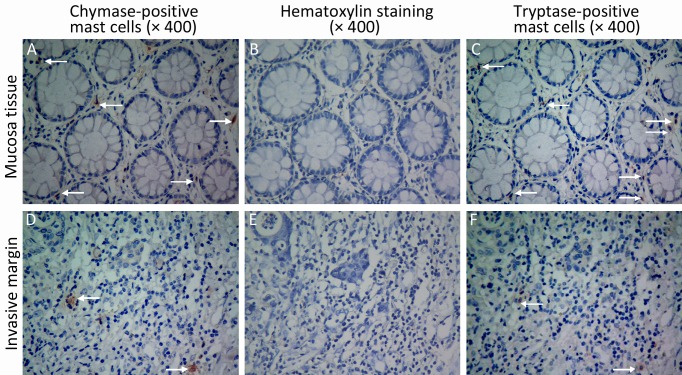

Tryptase and chymase staining were used to define the phenotypes of mast cells. Most of the mast cells in the mucosa and invasive margin showed similar tryptase and chymase staining, indicating that these cells display an MCTCphenotype (Figure 1). The density of mast cells was counted; the majority of the cells were located in adjacent normal colon mucosa, followed by the invasive margin, and least in the cancer stroma (Figure 2). MCCadjacent significantly increased when tumors developed from adenomas to advanced colon cancers (7.20±2.72 vs. 6.60±3.31 vs. 7.70±3.48 vs. 7.70±3.17 vs. 9.00±2.83, P<0.05), whereas no statistically significant difference existed for MCCinvasive among patients with stages I-IV colon cancer (Table 1). Finally, the relationship between mast cells and tumor microvessels was examined. It failed to show the related distribution of mast cells and microvessels in consecutive sections (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The phenotypes of mast cells. Mast cells were stained with chymase monoclonal antibody (×400 A and D), and tryptase monoclonal antibody (×400 C and F). B and E are negative controls (×400). Arrows indicate chymase-positive mast cells (A and D) and tryptase-postive mast cells (C and F).

Figure 2.

The distribution of mast cells in adenomas and cancers of the colon. The tryptase-positive mast cells were stained with an immunohistochemical assay (×400). MCCadjacent increased when tumors developed from adenomas to advanced colon cancer (A-E). Whereas no significant difference for MCCinvasive among patients with stages I-IV was observed (F-I). Rare mast cells were observed in the tumor stroma (J-N).

Figure 3.

The relationship between mast cells and blood vessels. Blood vessels were stained with CD31 monoclonal antibody (×400 A and C). Mast cells were stained with tryptase monoclonal antibody (×400 B and D). Tryptase-positive mast cell count was not positively related with CD-31 positive blood vessel count. Neither was the distribution. Arrows indicate CD-31 positive blood vessels (A and C), and tryptase-positive mast cells (B and D).

Relationship between MCC and Clinicopathologic Characteristics

The relationship between MCC and clinicopathologic parameters was analyzed. The results showed that MCCinvasive was not related to the conventional clinicopathologic parameters, such as TNM classification characteristics and hepatic metastases (Table 2). However, MCCadjacent was associated with pathologic classification, distant metastases, and the synchronous and meta- chronous hepatic metastases of colon cancer (Table 2).

Table 2. The association between MCC and clinicopathologic characteristics.

| Variable | n | MCCinvasive |

P | MCCadjacent |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤4 | >4 | ≤8 | >8 | ||||

| Age(year) | 0.093 | 0.389 | |||||

| ≤59 | 80 | 46 | 34 | 35 | 45 | ||

| >59 | 75 | 33 | 42 | 38 | 37 | ||

| Gender | 0.153 | 0.484 | |||||

| Male | 91 | 42 | 49 | 45 | 46 | ||

| Female | 64 | 37 | 27 | 28 | 36 | ||

| Location of primary tumor | 0.536 | 0.663 | |||||

| Left | 92 | 45 | 47 | 42 | 50 | ||

| Right | 63 | 34 | 29 | 31 | 32 | ||

| Pathologic classification | 0.436 | a0.029 | |||||

| Papillary + tubular | 132 | 69 | 63 | 67 | 65 | ||

| Other | 23 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 17 | ||

| Grade | 0.847 | 0.726 | |||||

| G1 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | ||

| G2 | 109 | 56 | 53 | 53 | 56 | ||

| G3 | 25 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 15 | ||

| G4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Depth of penetration | 0.396 | 0.054 | |||||

| T1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| T2 | 32 | 20 | 12 | 21 | 11 | ||

| T3 | 92 | 46 | 46 | 41 | 51 | ||

| T4 | 25 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 | ||

| Lymph node involvement | 0.352 | 0.089 | |||||

| N0 | 76 | 35 | 41 | 42 | 34 | ||

| N1 | 62 | 36 | 26 | 26 | 36 | ||

| N2 | 17 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 12 | ||

| Distant metastases | 0.970 | a0.008 | |||||

| M0 | 114 | 58 | 56 | 61 | 53 | ||

| M1 | 41 | 21 | 20 | 12 | 29 | ||

| Hepatic metastases | 0.997 | a0.027 | |||||

| No | 100 | 51 | 49 | 54 | 46 | ||

| Metachronous | 14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Synchronous | 41 | 21 | 20 | 12 | 29 | ||

Chi-square tests, aP<0.05, statistically significant.

Relationship between MCC and OS

Among the 155 colon cancer patients, 93 patients were alive after the 5-year follow-up. Thus, the 5-year survival rate was 60%. The MCCadjacent ranged from 1.40 to 20.20 MC/HP, with a median of 8.00 MC/HP. The MCCinvasive ranged from 0.20 to 15.00 MC/HP with a median of 4.00 MC/HP. According to Gulubova’s method, patients were then divided into high and low MCCadjacent and MCCinvasive groups by median values (8.00 MC/HP and 4.00 MC/HP, respectively)[9]. Based on univariate and multivariate analyses, neither MCCadjacent nor MCCinvasive was related to OS (Figures 4, 5 and Tables 3, 4).

Figure 4.

The relationship between the MCCinvasive and OS. No statistical significance was observed between the patients with MCCinvasive>4.0 MC/HP and those with MCCinvasive≤4.0 MC/HP. MCCinvasive, the number of tryptase-positive mast cells localized in the invasive margin.

Figure 5.

The relationship between the MCCadjacent and OS. No statistical significance was observed between the patients with MCCadjacent>8.0 MC/HP and those with MCCadjacent≤8.0 MC/HP. MCCadjacent, the number of tryptase-positive mast cells localized in adjacent normal colon mucosa.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of factors associated with OS (n=155).

| Variable | OS |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR, (95% CI) | P | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.831 (0.496-1.391) | 0.481 | |

| Age (>59 y vs. ≤59 y) | 0.986 (0.599-1.624) | 0.956 | |

| Location of primary tumor (right vs. left) | 0.919 (0.551-1.532) | 0.746 | |

| Grade (G4+G3 vs. G2+G1) | 2.238 (1.303-3.844) | 0.004a | |

| Pathologic classification (papillary+tubular vs. other) | 1.759 (0.758-4.083) | 0.189 | |

| Stage (IV+III vs. II+I) | 12.904 (5.850-28.465) | 0.000b | |

| Hepatic metastases (no vs. yes) | 0.037 (0.018-0.076) | 0.000b | |

| MCCadjacent (high vs. low)A | 1.427 (0.862-2.364) | 0.167 | |

| MCCinvasive(high vs. low) B | 0.821 (0.498-1.355) | 0.441 | |

A, MCCadjacenthigh, MCCadjacent>8.0 MC/HP; MCCadjacentlow, MCCadjacent≤8.0 MC/HP. B, MCCinvasivehigh,MCCinvasive>4.0 MC/HP; MCCinvasive low, MCCinvasive≤4.0 MC/HP. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. aP<0.05, bP<0.001, statistically significant.

Table 4. Multivariate Cox analysis of factors associated with OS (n=155).

| Variable | OS |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR, (95% CI) | P | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.054 (0.627-1.770) | 0.843 | |

| Age (>59 y vs. ≤59 y) | 1.142 (0.692-1.884) | 0.604 | |

| Location of primary tumor (right vs. left) | 1.368 (0.806-2.324) | 0.246 | |

| Grade (G4+G3 vs. G2+G1) | 1.680 (0.968-2.915) | 0.065 | |

| Pathologic classification (papillary+tubular vs. other) | 1.216 (0.518-2.853) | 0.653 | |

| Stage (IV+III vs. II+I) | 3.385 (1.372-8.348) | 0.000b | |

| Hepatic metastases (no vs. yes) | 0.069 (0.031-0.152) | 0.000b | |

| MCCadjacent (high vs. low) A | 0.985 (0.590-1.645) | 0.953 | |

| MCCinvasive(high vs. low) B | 0.639 (0.381-1.072) | 0.090 | |

A, MCCadjacenthigh, MCCadjacent>8.0 MC/HP; MCCadjacentlow, MCCadjacent≤8.0 MC/HP. B, MCCinvasivehigh, MCCinvasive>4.0 MC/HP; MCCinvasive low, MCCinvasive≤4.0 MC/HP. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. bP<0.001, statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Using immunohistochemistry, this study analyzed the distribution of mast cells in adenomas, colon cancers, and matched adjacent normal colon tissue. The results showed that MCCadjacent increased when tumors developed from adenomas to advanced colon cancers, although MCCadjacent was not a prognostic factor.

Most previous studies have shown that mast cell is an early and persistent infiltrating immune cell in colorectal cancers, acting before significant tumor growth and angiogenesis have occurred. After the switch to angiogenesis, mast cell assembles in the invasive margin or around the vessels, which is related to the malignant phenotypes or poor prognosis[8-17]. In contrast to those studies, this study showed that MCCinvasive was associated with neither the malignant phenotypes nor the survival of colon cancer patients. Additionally, in consecutive sections, the spatial relationship between mast cells and endothelial cells also failed to support the idea that mast cells could regulate angiogenesis. Both pieces of evidence supported the randomized distribution hypothesis of mast cells in tumor tissue, which had been observed in endometrial adenocarcinomas, non-small cell lung carcinomas, cutaneous mastocytomas, and melanomas[19,20].

Because the relationship between mast cells in the invasive margin and tumor progression was not observed, this study further analyzed the relationship between MCCadjacent and tumor progression. Mast cells reside in the mucosa in the digestive tract[21-23]. After activation, mast cells can produce and release mediators and cytokines, which are involved in the modulation of a wide variety of gastrointestinal, physiologic, and pathologic processes, such as the regulation of epithelial barriers, mucosal immune function, bacterial defense, motility, and visceral sensitivity[24-28]. As the role of mast cells in the adjacent normal colon mucosa in the progression of colon cancers had not been examined, this study examined the phenotypes of mast cells with tryptase and chymase staining. The results showed that mast cells in normal colon mucosa were mostly MCTC phenotype. Secondly, this study observed that the increased MCCadjacentwas associated with pathologic classification, distant metastases, and the synchronous and metachronous hepatic metastases of colon cancer. This suggested that mast cells in the adjacent normal colon mucosa have the potential for long-distance regulation, as peripheral mature mast cells ordinarily do not circulate in the blood. It remains unknown how mast cells in the mucosa interact with colon cancers. Therefore, it is important to analyze the underlying mechanism by which mast cells in adjacent normal colon mucosa affect colon cancer progression, especially with hepatic metastases. This mechanism may hold targets for new therapeutics to be developed in the future[29-31].

This study showed that mast cells in the adjacent normal colon mucosa rather than mast cells in the invasive margin were associated with the progression of colon cancer, indicating that mast cells might be involved in tumor progression via a long-distance regulatory mechanism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Witz IP. The tumor microenvironment: the making of a paradigm. Cancer Microenviron 2009;2(Suppl 1):9-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Q, Peng RQ, Wu XJ, et al. The density of macrophages in the invasive front is inversely correlated to liver metastasis in colon cancer. J Transl Med 2010;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao YF, Peng RQ, Li J, et al. The paradoxical patterns of expression of indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase in colon cancer. J Transl Med 2009;7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maltby S, Khazaie K, McNagny KM. Mast cells in tumor growth: angiogenesis, tissue remodelling and immune-modulation. BiochimBiophysActa 2009;1796:19-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ribatti D, Crivellato E.The controversial role of mast cells in tumor growth. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2009;275:89-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galinsky DS, Nechushtan H. Mast cells and cancer--no longer just basic science. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2008;68:115-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng SH, Deng H, Yang JF, et al. Significance and relationship between infiltrating inflammatory cell and tumor angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:6521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naghshvar F, Torabizadeh Zh, Emadian O, et al. Correlation of cyclooxygenase 2 expression and inflammatory cells infiltration in colorectal cancer. Pak J Biol Sci 2009;12:98-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulubova M, Vlaykova T.Prognostic significance of mast cell number and microvascular density for the survival of patients with primary colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:1265-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashiwase Y, Inamura H, Morioka J, et al. Quantitative analysis of mast cells in benign and malignant colonic lesions: immunohistochemical study on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2008;36:271-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yodavudh S, Tangjitgamol S, Puangsa-art S.Prognostic significance of microvessel density and mast cell density for the survival of Thai patients with primary colorectal cancer. J Med Assoc Thai 2008;91:723-32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taweevisit M.The association of stromal mast cell response and tumor cell differentiation in colorectal cancer. J Med Assoc Thai 2006;89(Suppl 3):S69-73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acikalin MF, Oner U, Topcu I, et al. Tumor angiogenesis and mast cell density in the prognostic assessment of colorectal carcinomas. Dig Liver Dis 2005;37:162-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan SY, Fan Y, Luo HS, et al. Prognostic significance of cell infiltrations of immunosurveillance in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1210-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen HJ, Hansen U, Christensen IJ, et al. Independent prognostic value of eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in colorectal cancer tissue. J Pathol 1999;189:487-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lachter J, Stein M, Lichtig C, et al. Mast cells in colorectal neoplasias and premalignant disorders. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:290-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher ER, Paik SM, Rockette H, et al. Prognostic significance of eosinophils and mast cells in rectal cancer: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (protocol R-01). Hum Pathol 1989;20:159-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlini MJ, Dalurzo MC, Lastiri JM, et al. Mast cell phenotypes and microvessels in non-small cell lung cancer and its prognostic significance. Hum Pathol 2010;41:697-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidolin D, Nico B, Crivellato E, et al. Tumoral mast cells exhibit a common spatial distribution. Cancer Lett 2009;273: 80-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nechushtan H.The complexity of the complicity of mast cells in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010;42:551-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galli SJ, Tsai M. Mast cells: versatile regulators of inflammation, tissue remodeling, host defense and homeostasis. J Dermatol Sci 2008;49:7-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli SJ, Grimbaldeston M, Tsai M. Immunomodulatory mast cells: negative, as well as positive, regulators of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:478-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galli SJ, Kalesnikoff J, Grimbaldeston MA, et al. Mast cells as "tunable" effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:749-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metz M, Grimbaldeston MA, Nakae S, et al. Mast cells in the promotion and limitation of chronic inflammation. Immunol Rev 2007; 217:304−28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat Immunol 2008;9:1215-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metz M, Maurer M: Mast cells--key effector cells in immune responses. Trends Immunol 2007;28:234-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raithel M, Weidenhiller M, Abel R, et al. Colorectal mucosal histamine release by mucosa oxygenation in comparison with other established clinical tests in patients with gastrointestinally mediated allergy. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:4699-705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farhadi A, Fields JZ, Keshavarzian A. Mucosal mast cells are pivotal elements in inflammatory bowel disease that connect the dots: stress, intestinal hyperpermeability and inflammation . World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:3027-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groot Kormelink T, Abudukelimu A, Redegeld FA. Mast cells as target in cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Des 2009;15:1868-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zdolsek J, Eaton JW, Tang L. Histamine release and fibrinogen adsorption mediate acute inflammatory responses to biomaterial implants in humans. J Transl Med 2007;5:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasiuk A, de Vries VC, Hartmann K, et al. Mast cells as regulators of adaptive immunity to tumors. ClinExpImmunol 2009;155:140-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]