Summary

Cytokine-activated STAT proteins dimerize and bind to high-affinity motifs, and N-terminal domain-mediated oligomerization of dimers allows tetramer formation and binding to low-affinity tandem motifs, but the functions of dimers versus tetramers are unknown. We generated Stat5a-Stat5b double knock-in (DKI) N-domain mutant mice that form dimers but not tetramers, identified cytokine-regulated genes whose expression required STAT5 tetramers, and defined dimer versus tetramer consensus motifs. Whereas Stat5- deficient mice exhibited perinatal lethality, DKI mice were viable; thus, STAT5 dimers were sufficient for survival. Nevertheless, STAT5 DKI mice had fewer CD4+CD25+ T cells, NK cells, and CD8+ T cells, with impaired cytokine-induced and homeostatic proliferation of CD8+ T cells. DKI CD8+ T cell proliferation following viral infection was diminished and DKI Treg cells did not efficiently control colitis. Thus, tetramerization of STAT5 is dispensable for survival but is critical for cytokine responses and normal immune function, establishing a critical role for tetramerization in vivo.

Introduction

Signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT proteins) play vital roles in modulating gene expression in response to cytokines, interferons, and various growth factors and are critical for development and cellular function (Leonard and O'Shea, 1998; Levy and Darnell, 2002). Cytokines and interferons activate JAK kinases, which in turn phosphorylate key tyrosines on their receptors, allowing the binding of STAT proteins via their SH2 domains to these phosphotyrosine docking sites. The STAT proteins in turn are then tyrosine phosphorylated, allowing their dimerization (Leonard and O'Shea, 1998; Levy and Darnell, 2002). Additionally, at least some STAT proteins can form tetramers via N-terminal domain-mediated interactions, with binding to tandem binding sites (Vinkemeier et al., 1996; Xu et al., 1996), but the role of STAT tetramerization in vivo is poorly understood. Here, we have investigated the role of STAT5A and STAT5B tetramerization in vivo.

Of the seven mammalian STAT proteins: STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6, STAT5A and STAT5B are particularly similar, with ~91% amino acid identity in humans and mice. STAT5A and STAT5B are encoded by head-to-head genes on human chromosome 17q11.2 (Lin et al., 1996) and mouse chromosome 11 (Copeland et al., 1995) and can be activated by prolactin, growth hormone, IL-2, IL-3, IL-5, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, IL-21, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (Leonard and O'Shea, 1998; Rochman et al., 2009). Stat5a−/− mice have defective mammary gland development and lactogenesis due to defective prolactin signaling (Liu et al., 1997), whereas Stat5b−/− mice have a loss of sexually dimorphic growth due to defective growth hormone signaling (Udy et al., 1997). Mice with hypomorphic expression of truncated forms of both STAT5A and STAT5B exhibit more severe defects in prolactin and growth hormone signaling (Teglund et al., 1998), as well as defective erythropoiesis (Socolovsky et al., 1999), and complete deletion of both Stat5a and Stat5b results in >99% perinatal lethality due to severe anemia and potentially other defects (Cui et al., 2004).

In the immune system, both Stat5a−/− (Nakajima et al., 1997) and Stat5b−/− (Imada et al., 1998) mice exhibit decreased IL-2-induced IL-2 receptor α chain (IL-2Rα) expression. STAT5A and STAT5B have both overlapping and distinctive functions, with STAT5B playing a more critical role for natural killer (NK) cell development and function (Imada et al., 1998; Moriggl et al., 1999). The few Stat5a−/−Stat5b−/− mice that survive have defective development of CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, NK cells, and B cells (Yao et al., 2006).

Activated STAT1 STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, and STAT5B bind to TTCN3GAA γ-interferon-activated sequence (GAS) motifs as dimers, whereas STAT6 prefers TTCN4GAA motifs (Leonard and O'Shea, 1998). For at least STAT1, STAT4, and STAT5, N-terminal interactions between STAT dimers allows binding to two or more tandem GAS motifs as higher order complexes (John et al., 1996; John et al., 1999; Meyer et al., 1997; Vinkemeier et al., 1996; Vinkemeier et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1996). Based on the structure of the STAT4 N-domain (Chen et al., 2003), we identified corresponding residues in STAT5 proteins and generated tetramer-deficient knock-in (KI) mice for Stat5a and/or Stat5b. In contrast to perinatal lethality in Stat5a−/−Stat5b−/− mice, DKI mice were viable, underscoring the importance of STAT5 dimers and indicating that STAT5 tetramers are not required for survival. Nevertheless, gene expression analysis revealed defective expression of a subset of genes in IL-2-induced DKI T cells. We also used ChIP-Seq methodology to identify genome-wide STAT5A and STAT5B dimer and tetramer binding sites and established consensus binding motifs for STAT5A and STAT5B, including optimal spacing between tandemly-linked GAS motifs for tetramers. Correlating ChIP-Seq and gene expression data allowed us to identify genes whose expression is regulated by STAT5 tetramers but not dimers, clarifying the role of STAT5 tetramerization in vivo. Moreover, whereas STAT5 dimers but not tetramers were essential for viability and normal growth, tetramer-deficient mice had decreased CD4+CD25+ T cells and NK cells, diminished cytokine-induced proliferation of DKI CD8+ T cells, increased apoptosis of DKI CD8+ T cells upon IL-2-withdrawal, and impaired homeostatic proliferation of DKI CD8+ T cells in vivo. DKI mice also exhibited defective expansion of viral-specific DKI CD8+ T cells following infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) or adenovirus 5 and had diminished regulatory T (Treg) cell function as evaluated by suppression of colitis. These data underscore key roles of STAT5 tetramerization in normal immune function, with most of the STAT5 tetramer-regulated genes requiring STAT5 tetramers for their optimal expression. These findings have implications for other STAT proteins that can form tetramers, with potential implications for other transcription factors as well.

Results

Generating STAT5 tetramer-deficient mice

Our laboratory previously showed that STAT5A and STAT5B homodimers share core TTC(T/C)N(G/A)GAA GAS motifs and that STAT5A tetramers often bind to imperfect tandem GAS motifs not retaining a consensus TTCN3GAA motif (Soldaini et al., 2000). However, that study used a DNA binding site selection analysis with oligonucleotides containing only 26 nucleotides of random sequence, thus limiting information on optimal spacing between tandem motifs. Here, we sought to identify the range of STAT5 tetramer-regulated genes to characterize the basis for tetramer binding and moreover to elucidate the biological role of STAT5 tetramerization in vivo.

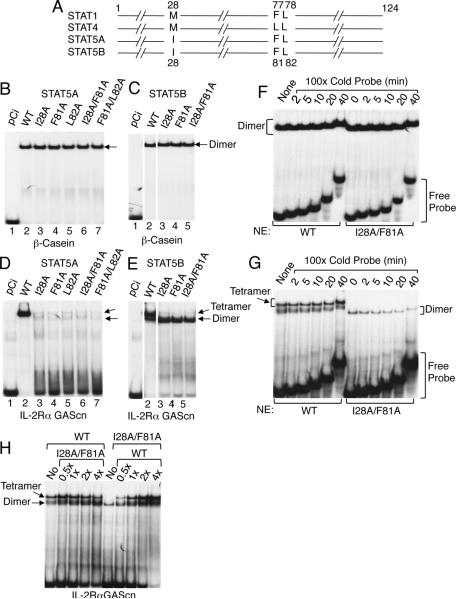

Analysis of the STAT1 and STAT4 N-domain crystal structures revealed that M28, F77, and L78 (STAT1) and M28, L77, and L78 (STAT4) were required for tetramer formation (Chen et al., 2003). We aligned the N-domains of all mouse STAT proteins except STAT2 and identified I28, F81, and L82 as the corresponding residues in STAT5A and STAT5B (Figure 1A and Figure S1A). Mutation of these residues to alanines, alone or in combination, did not affect binding to the β-casein probe (Figure 1B for STAT5A and Figure 1C for STAT5B), which contains a single GAS motif and binds only STAT5 dimers, but it abrogated tetrameric binding to the IL-2Rα promoter PRRIII GAScn probe (Figure 1D for STAT5A and Figure 1E for STAT5B), which favors tetrameric binding (John et al., 1999). Interestingly, dimeric binding increased when tetrameric binding was prevented, particularly for STAT5B (Figure 1D and 1E). Thus, I28, F81, and L82 are required for STAT5 tetramer but not dimer formation. As expected, the tetramer-defective mutant STAT5 proteins exhibited similar off-rates to those observed for WT STAT5 protein with the β-casein probe (Figure 1F), which only binds dimers. Interestingly, the off-rate of mutant STAT5 was slightly increased for dimer binding to the IL-2Rα GAScn probe (Figure 1G), which can bind tetramers as well as dimers. As anticipated, when an increasing amount of tetramer-defective STATB protein was mixed with a fixed amount of WT STAT5B and added to a constant amount of probe, the amount of dimer binding increased, as would be expected by the addition of more dimer protein. Conversely, the amount of both tetramer and dimer increased when an increasing amount of WT STATB was mixed with a fixed amount of the mutant STAT5B protein, as would be expected by the addition of more tetramer and dimer. (Figure 1H).

Figure 1. I28, F81, and L82 in the N-domains of STAT5A and STAT5B are required for tetramer formation.

(A) Schematic of conserved amino acids required for tetramer binding in STAT1, STAT4, STAT5A, and STAT5B, based on data for STAT1 and STAT4 (Chen et al., 2003). The numbers above (for STAT1 and STAT4) or below (for STAT5A and STAT5B) indicate the amino acid positions. (B through E) EMSAs were performed using [32P]-labeled β-casein (B and C) or IL-2Rα GAScn (D and E) probes and nuclear extracts from 293T+ cells transfected with plasmids directing expression of IL-2Rβ, γc, and JAK3 as well as pCi (B to E, lane 1), pCi-Stat5a (B and D, lanes 2 to 7), or pCi-Stat5b (C and E, lanes 2 to 5), as indicated. Arrows indicate dimer or tetramer binding. (F and G) Off-rates of WT and mutant STAT5 proteins from a site from the bcasein gene, which binds as dimers (F) or a site from IL-2Rα gene, which binds both STAT5 tetramers and dimers (G). (H) Titration of binding WT and mutant STAT5B proteins. The experiments in panel B-H were performed twice.

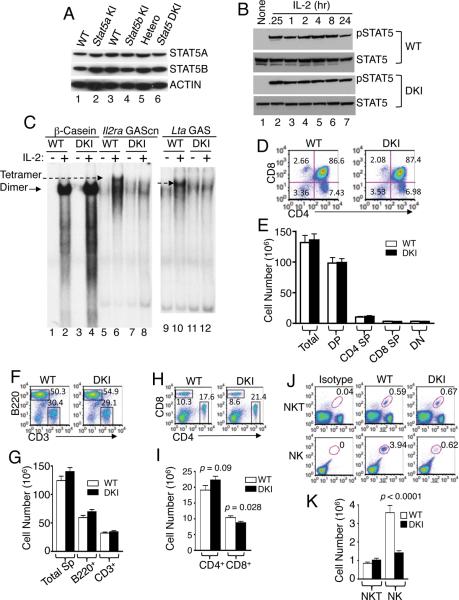

To study the role of STAT5 tetramerization in vivo, we targeted the I28 and F81 codons in Stat5a (Figure S2A) and Stat5b (Figure S2B) and generated single and double knockin (DKI) ES cells (Figure S2C for Stat5a, Figure S2D for Stat5b, and Figure S2E for targeting of both Stat5 genes), which we used to generate KI mice. Expression of WT and mutant Stat5 alleles was similar (Figure 2A), and IL-2 induced rapid and sustained tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 proteins with similar kinetics in WT and DKI T cells (Figure 2B). Thus, disrupting STAT5 tetramer formation did not affect STAT5 protein levels or the kinetics of IL-2-induced phosphorylation. We isolated nuclear extracts and used EMSAs to confirm that the DKI T cells had normal IL-2-induced STAT5 binding to a probe that selectively binds dimers but not to a probe that selectively binds tetramers (Figure 2C). Moreover, Stat5a KI, Stat5b KI, and Stat5a and Stat5b DKI mice were viable, normal in weight (Figure S2F), and had normal peripheral leukocyte numbers (Figure S2G). STAT5 tetramer-deficient neonates had mild decreases in hematocrit, red blood cell numbers, and hemoglobin levels, but levels normalized by adulthood (Figure S2H).

Figure 2. Normal expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 proteins but decreased peripheral NK and CD8+ T cells in DKI mice.

(A). Western blots of STAT5A and STAT5B expression in splenic T cells from Stat5a KI (lane 2), Stat5b KI (lane 4), and Stat5a/Stat5b DKI (lane 6) mice versus WT mice (lanes 1, 3, 5). Actin levels are also shown as a loading control. (B). Representative western blots of two experiments showing tyrosine phosphorylated and total STAT5 protein in WT (upper panels) and DKI (lower panels) splenic T cells stimulated by IL-2 (100 U/ml) for the indicated times. Prior to IL-2 stimulation, cells were preactivated by plate-bound anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) for two days and rested overnight. This experiment was performed two times. (C). EMSA for dimeric STAT5 binding (β-casein probe, lanes 2 and 4) and tetrameric STAT5 binding (for Il2ra GAScn, lanes 6 and 8 and Lta GAS, lanes 10 and 12) using nuclear extracts from IL-2-treated WT and DKI T cells. Dimer (arrow with solid line) and tetramer (arrow with dash line) complexes are indicated. This experiment was performed three times. (D and E) CD4 and CD8 flow cytometric profile of thymocytes from WT and DKI mice (n = 8) (D) with cell numbers indicated (E). (F–K) Flow cytometric profiles and cellularity of spleens from WT and DKI mice. (F–I) WT and DKI splenocytes were isolated and stained with anti-CD3 versus anti-B220 (F and G) or anti-CD4 vs. anti-CD8 (H and I) (n = 20). (J and K) Splenocytes from WT and DKI mice (n = 16) were stained as TCRβ+CD1d-PBS57+ NKT cells or CD3−NK1.1+CD122+ NK cells.

Decreased peripheral CD8+, and NK cells in DKI mice

In contrast to the severely impaired T-cell development in mice lacking Stat5a and Stat5b (Yao et al., 2006), DKI mice had normal numbers of thymocytes, including double positive (DP), double negative (DN), and CD4+ and CD8+ single positive (SP) subpopulations (Figure 2D and 2E). Interestingly, the DKI mice had a slightly increased splenic B:T cell ratio (Figure 2F) but total numbers of splenic B and T cells were similar to WT (Figure 2G). The CD4:CD8 ratio was modestly increased (Figure 2H), with slightly decreased CD8+ T cells (p < 0.05) and a trend towards slightly increased CD4+ T cells (Figure 2I). NKT cell numbers were normal, but NK cells were significantly decreased (Figure 2J and 2K), indicating a requirement for STAT5 tetramers for NK development. As expected, development of Mac-1+, Gr.1+ and Ter119+ cells was normal (Figure S2I). Thus, STAT5A and STAT5B dimers are sufficient for normal thymic development, whereas tetramers are required for normal numbers of peripheral CD8+ T and NK cells.

Previously, STAT5 tetramers were shown to be important for IL-2-induced IL-2Rα (CD25) promoter activity (John et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2001). Consistent with this, IL-2-induced IL-2Rα expression was abrogated in CD4+ and CD8+ splenic T cells from DKI mice and slightly decreased in Stat5a KI and Stat5b KI T cells (Figure 3A). The defect tended to be greater in Stat5b KI mice, consistent with greater lymphoid abnormalities in Stat5b−/− (Imada et al., 1998) than in Stat5a−/− (Nakajima et al., 1997) mice.

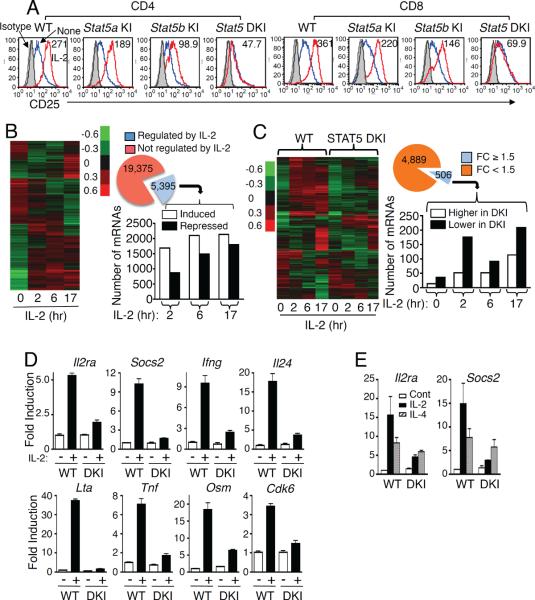

Figure 3. Altered gene expression in DKI T cells.

(A) Preactivated splenic T cells were rested overnight and re-stimulated with IL-2 for 1 day prior to determining CD25 expression in CD4+ (top row) and CD8+ (bottom row) T cells. IL-2-induced CD25 expression levels are indicated as mean fluorescence (MFI). Isotype control (IgG), IL-2, and untreated samples are shown in gray, red, and blue, respectively. This experiment was performed three times. (B) On the left is a hierarchical clustering analysis of gene expression profiles regulated by IL-2 in WT T cells. Also shown is a pie graph of the number of mRNAs not regulated (red) or regulated (blue) by IL-2. For IL-2-regulated mRNAs, the linked bar graph indicates the number of mRNAs whose expression was induced (open bars) or repressed (solid bars) at each time point. (C) Shown on the left is the hierarchical clustering analysis of IL-2-regulated mRNAs in DKI as compared with WT T cells. Also shown is a pie graph of the number of IL-2-regulated mRNAs whose expression was not affected (orange) or affected (blue) in DKI T cells. For the 506 mRNAs whose expression was affected, the linked bar graph indicates the number of genes whose expression was higher (open bars) or lower (solid bars) in the DKI T cells. For the experiments in panels B and C, 5 replicates of WT and DKI splenic T cells were analyzed for each treatment. (D and E) Validation of (D) STAT5 tetramer-dependent IL-2-induced gene expression and (E) STAT5 tetramer-independent IL-4-induced gene expression. The experiments described in panel D were performed 4 times and in panel E were performed twice. The cDNA inputs were normalized after RT-PCR based on the cycle number for Rpl7 primers, as Rpl7 expression was constant under our experimental conditions. Shown are the relative expression of triplicate samples of a representative experiment.

IL-2-regulated genes whose expression requires STAT5 tetramers

Using Affymetrix arrays, we next compared gene expression profiles in WT and DKI splenic T cells that were pre-activated, rested, and re-stimulated with IL-2. In WT T cells, we identified 5395 mRNAs whose expression had a fold change (FC) >1.5 fold, with <20% false discovery rate (FDR) (Figure 3B), with 1690, 2102, and 2137 mRNAs induced and 875, 1489, and 1796 mRNAs suppressed at 2, 6, and 17 hr by IL-2, respectively (Figure 3B, bar graph; Table S1). Among the 5395 IL-2 regulated mRNAs, 506 (9.4%) were significantly altered (FC ≥ 1.5) in Stat5a-Stat5b DKI T cells relative to WT cells (Figure 3C and Table S2), with more repressed than induced genes in the DKI T cells (Figure 3C, bar graph). These included genes encoding cytokines and molecules that regulate cytokine signaling and functions (e.g., Il24, Il2ra, Ifng, Lif, Lta, Osm, Tnf, Fyn, Fes, Rgs1, Cish, Socs1, Socs2, Socs3, Myc, Mix1,Bcl2, Cdk6, Fasl, Irf4, Irf8, Foxo3a, Foxp1, and Nfkb1) (Table S3). For some of these genes, we used RT-PCR to confirm that IL-2-induced expression was essentially abolished (e.g., Socs2 and Lta) or greatly diminished (e.g., Il2ra, Ifng, Il24, Tnf, Osm, and Cdk6) in DKI T cells (Figure 3D). IL-4 can also induce Il2ra and Socs2 mRNA in WT T cells, but as expected given that IL-4 primarily activates STAT6 rather than STAT5, the induction of these genes by IL-4 was not significantly affected in DKI T cells (Figure 3E), indicating the specificity of the defect. Interestingly, in WT T cells, IL-2-induced genes tended to have more significant p values than IL-2 suppressed genes, but in DKI cells, the repressed genes had lower p values (Figure S3), suggesting a dominant role for STAT5 tetramers in gene induction rather than repression in T cells, particularly for genes involved in gene regulation (Figure S3 and Tables S1 and S2). Thus, a subset of IL-2-regulated genes is specifically regulated by STAT5 tetramers in T cells, and these genes are preferentially induced rather than repressed by IL-2.

STAT5 dimer and tetramer consensus-binding sites

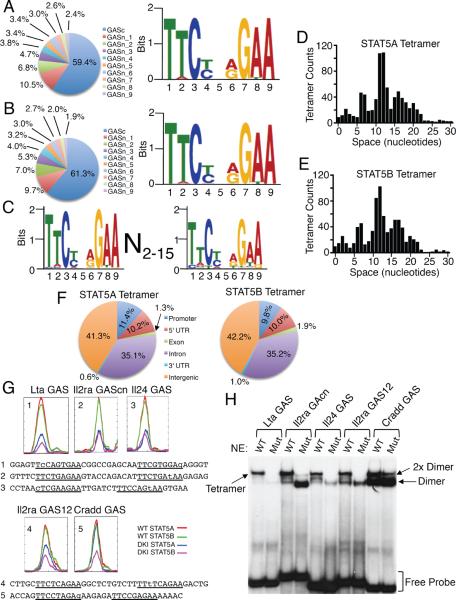

To identify motifs for STAT5A and STAT5B dimer and tetramer binding, we used ChIP-Seq and WT and DKI T cells cultured with or without IL-2 for 1 hr. Using MACS (Model-based Analysis for ChIP-Seq (Zhang et al., 2008)), we compared untreated vs. IL-2-induced WT samples after subtracting background IgG control levels (see Methods and Figure S4A) and identified 16,957 STAT5A and 17,418 STAT5B sites (Table S4), including those binding to both dimers and tetramers. The genome-wide distributions of STAT5A and STAT5B binding sites were similar (Figure S4B). Analysis of STAT DKI ChIP-Seq data revealed 14,770 STAT5A and 12,568 STAT5B sites that presumptively only bind to dimers (Table S4). Interestingly, as compared to the distribution of all STAT5A and STAT5B sites (Figure S4B), dimers somewhat preferentially bound in promoter and 5' UTR regions, with slightly decreased frequency in intergenic and 3' UTR regions and exons (Figure S4C). To de novo discover motifs recognized by STAT5A and STAT5B dimers, we analyzed the 10% top sites in DKI data sets based on the most significant p values using MEME (Bailey and Elkan, 1994). As expected, we defined almost identical motifs for STAT5A (Figure 4A and Figure S4D) and STAT5B (Figure 4B and Figure S4E), with favored binding to canonical TTCN3GAA GAS motifs; nucleotides at positions 1, 3, 7, and 9 were the most conserved.

Figure 4. Distribution of STAT5 binding sites and STAT5 dimer and tetramer motifs.

(A and B) Consensus dimer motifs for STAT5A (A) and STAT5B (B). The pie graphs show the top 10 binding motifs for STAT5A (A) and STAT5B (B), as detailed in Supplemental Figure S4D and S4E. (C) Consensus tetramer motif for STAT5A and STAT5B. (D and E) Spacing distribution between tandemly-linked GAS or GAS-like motifs for STAT5A (D) and STAT5B (E). (F) Genome-wide distributions of STAT5A (top) and STAT5B (bottom) tetramer binding sites. 5' UTR, 3' UTR, promoter, and intergenic regions were defined according to Ref Seq data base (February 2006 assembly), and promoters defined as 5 kb upstream of TSS. (G) STAT5 binding motifs for Lta GAS, Il2ra GAScn, Il24 GAS, Il2ra GAS12, and Cradd GAS identified by ChIP-Seq analysis. Color-coded lines indicate chromatin from WT (red and green) or DKI (blue and magenta) T cells immunoprecipitated with anti-STAT5A (red and blue) and STAT5B (green and magenta). Below the graphs are the sequences of the probes for Lta GAS (1), Il2ra GAScn (2) Il24 GAS (3), Il2ra GAS12 (4), and Cradd GAS (5); the GAS and GAS-like motifs are underlined and mismatches are in lower case. (H) EMSA using WT or tetramer-defective mutant STAT5B proteins and GAS motifs from Lta, Il24, Il2ra, and Cradd, based on ChIP-Seq analysis. Tetramer, 2× dimer, dimers, and free probes are indicated based on mobility and whether or not a given probe binds to mutant STAT5B protein. The experiment in panel H was performed 3 times.

To identify motifs for STAT5 tetramers, we analyzed sites present in IL-2-induced WT samples that were absent or greatly diminished in IL-2-induced DKI samples (Figure S4A). We selected sequences with canonical GAS or GAS-like motifs with only single mismatches (Figure S4F–S4H). ~50% of these sites had a second GAS-motif, and we defined the consensus STAT5 tetramer motif as T(T/A)C(T/C)N(A/G)G(A/T)AN2–15(T/C)(T/A)(C/T)(T/C)N(A/G/T)G(A/T)A (Figure 4C), with similar spacing between the GAS and/or GAS-like motifs for STAT5A (Figure 4D) and STAT5B (Figure 4E). As expected, the second (more 3') GAS motif was typically more degenerate than the first (Figure 4C) and more degenerate than the motifs for binding STAT5A and STAT5B dimers (Figs. 4A and 4B). Tetramer binding was facilitated with a spacing of 6–7 bp, decreased at 8–9 bp, and most favored at 11–12 bp; another slight increase occurred at ~15–16 bp, followed by a decline, with essentially undetectable tetramer binding at spacing >22 bp. More than 76% of the sites had a spacing of 6–17 bp between the GAS or GAS-like motifs, with 11.8% of motifs having spacing of 6–7 bp, 30.1% spacing of 11–12 bp, and 11.5% spacing of 16–17 bp. Our earlier DNA binding selection assay revealed a peak at 6–7 bp (Soldaini et al., 2000), but the short random oligonucleotides used in that analysis did not allow the identification of the optimal spacing of 11–12 bp. Interestingly, as compared to dimer binding sites (Figure S4C), STAT5 tetramer binding sites were relatively enriched in introns and decreased in the promoter regions (Figure 4F).

Comparing gene expression and ChIP-Seq data from WT and DKI cells revealed that 2,266 of the IL-2 regulated genes contained STAT5 dimer or tetramer binding sites. More of these were induced (1413) than repressed (859) by IL-2 in WT T cells. Genes whose IL-2-induced expression was significantly altered in Stat5a-Stat5b DKI T cells and that exhibited lower ChIP-Seq binding than in WT T cells presumptively were directly regulated by STAT5 tetramers. Of the 506 genes whose regulation by IL-2 was significantly increased or decreased in DKI T cells, 417 corresponded to genes in RefSeq and could be analyzed for tetramer binding sites. Of these, 105 had STAT5 tetramer motifs within 5 kb 5' of the TSS or within the gene body. These genes were all expressed at lower levels in DKI than in WT T cells, whereas genes whose expression was significantly higher in DKI T cells did not contain STAT5 tetramer binding sites. Thus, STAT5 tetramers preferentially mediate gene induction rather than repression.

Based on ChIP-Seq analysis (Figure 4G), we further evaluated in vitro binding by EMSA (Figure 4H) to probes containing tandemly-linked GAS and GAS-like motifs and corresponding to sites that appear to exhibit “good”, “moderate”, or “weak” binding as tetramers. By ChIP-Seq, the Lta gene preferentially bound tetramers, and correspondingly, a probe from this gene predominantly bound tetramers and exhibited only weak binding to tetramer-defective STAT5 proteins. Similar results were observed with probes corresponding to the Il2ra GAScn, Il24 GAS, and a newly identified tetramer binding site in the 1st intron of Il2ra gene that we denote as Il2ra GAS12, but these probes also bound dimers, as was especially apparent when tetramer-defective STAT5 proteins were used. The Cradd GAS probe mainly bound dimers, to a lesser extent “2× dimers” (two dimers that simultaneously yet independently bind without requiring an N-domain interaction between them), and exhibited least binding to tetramers. Therefore, it is likely that both the nucleotide composition of the GAS and GAS-like motifs and the spacing between GAS and GAS-like motifs influences whether a given sequence binds tetramers and/or 2× dimers or just dimers. Thus, we not only discovered a vital role for tetramers in regulating a set of IL-2-induced genes but also defined the motifs that mediate STAT5 dimer and tetramer binding.

STAT5 tetramers are required for CD8+ T cell survival and proliferation

Because many genes regulated by STAT5 tetramers control proliferation and cell cycle progression (Table S3), we hypothesized that DKI cells would have diminished cytokine-mediated proliferation. Indeed, IL-2-induced [3H]-thymidine incorporation was decreased (Figure 5A). High dose IL-2 (100 U/ml, 2 nM), which titrates most IL-2Rβ/γc intermediate affinity IL-2 receptors, or even 500 U/ml (10 nM), could not correct this defect (Figure 5A), indicating that it was not solely due to decreased IL-2Rα expression and that other STAT5 tetramer-dependent genes must be involved. Anti-CD3 + anti-CD28-induced proliferation of DKI cells was almost normal (Figure 5B), indicating that there is no intrinsic proliferative defect in these cells.

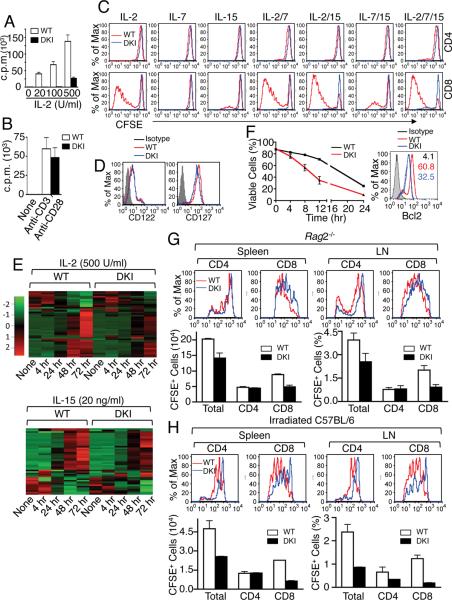

Figure 5. STAT5 tetramers are required for cytokine-dependent CD8+ T cell proliferation, survival, and homeostatic proliferation.

(A and B) Proliferation of STAT5 DKI T cells in response to IL-2 (A) or TCR (B) stimulation. Shown is one of three (A) or two (B) experiments for [3H]-thymine incorporation assay of purified mouse splenic T cells from STAT5 DKI mice and WT littermates (n = 3) cultured with IL-2 (A) or of anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 (B). (C) Shown are CFSE dilution profiles of WT and DKI splenic CD8+ T cells in response to indicated cytokine stimulations on day 5. The numbers show the percentage of cells that have undergone cell division, based on CFSE dilution. This experiment was performed 4 times. (D) IL-2Rβ (CD122) and IL-7Rα (CD127) expression in DKI (blue lines) and WT (red lines) CD8+ T cells. This experiment was performed 3 times. (E) Heat map of IL-2- and IL-15-regulated genes that are involved in cell cycle and proliferation whose expression is significantly affected in DKI CD8+ T cells. The data were from pooled splenic CD8+ T cells from WT (n = 10) and from DKI (n = 10) mice. (F) Purified WT and DKI spleen T cells were cultured for 5 days with 500 U/ml of IL-2, viable CD8+ T cells (%) after IL-2 withdrawal were determined at indicated time points as CD8+Annexin V−7AAD− cells. The data shown were derived from two independent experiments. Right, BCL2 expression in WT (red) and DKI (blue) CD8+ T cells was determined by surface staining with anti-CD8 and intracellular staining with Ig control (gray) or anti-BCL2 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values indicate MFI. Shown is one of two independent experiments. (G and H) Defective homeostatic proliferation of DKI CD8+ T cells in lymphopenic hosts. CFSE dilution profiles are shown in the top portions of panels G (Rag2−/− recipients) and H (irradiated C57BL/6 recipients). The cell number (spleen) and percentage (lymph nodes) are shown in the lower portions of panels G and H. The experiments in panels F–H were performed 2 times.

We next compared the proliferative response of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to other γc family cytokines that use STAT5. As expected, WT CD4+ T cells only weakly proliferated in response to IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, or combinations of these cytokines, but no proliferation was observed in DKI CD4+ T cells (Figure 5C). In contrast to WT CD4+ T cells, strong proliferation of WT CD8+ T cells was seen with IL-2, IL-15, IL-2 + IL-7, IL-2 + IL-15, IL7 + IL-15, or a combination of all three cytokines. CFSE dilution was markedly decreased in DKI CD8+ T cells in response to all combinations of cytokines (Figure 5C). Thus, STAT5 tetramers are vital for proliferation in response to these cytokines. Differences in receptor expression could not explain these diminished responses, as IL-2Rβ and IL-7Rα expression was only minimally lower in the DKI CD8+ T cells (Figure 5D). Consistent with the in vitro proliferative defect of DKI CD8+ T cells to these cytokines, IL-2- and IL-15-induced expression of genes involved in cell cycle progression and proliferation was significantly lower in DKI than in WT CD8+ T cells (Figure 5E and Tables S5A–C). In addition, there was no apparent increase in cell death in freshly isolated DKI CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Figure S5A) or in response to IL-2, IL-7, and/or IL-15 (Figure S5B and Figure S5C), even though BCL2 expression was moderately lower in these cells (Figure S5D). However, DKI CD8+ T cells were more susceptible than WT cells to apoptosis after IL-2 withdrawal (Figure 5F, left panel) and had decreased BCL2 levels (Figure 5F, right panel), indicating that STAT5 tetramers are required for lymphocyte viability as well as proliferation.

We also examined the frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ memory phenotype CD44hiCD62hi T cells and found they were less abundant, whereas the frequency of naive phenotype CD44loCD62hi T cells was greater in DKI than in WT cells (Figure S5E). When cultured in medium alone, the kinetics of naïve CD4+ T cell death was relatively similar in WT and DKI mice, although the DKI cells reproducibly had a slightly faster decline in viability (Figure S5F). This was more evident in naïve DKI CD8+ T cells (Figure S5G), consistent with an increased apoptosis of DKI CD8+ T cell after IL-2 withdrawal (Figure 5F). In the presence of IL-7, however, both WT and DKI naïve CD4+ (Figure S5F) and CD8+ (Figure S5G) T cells were similarly resistant to cell death. This correlated with similar IL-7-induced BCL2 levels in WT and DKI CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, although the levels in DKI cells were slightly lower than in WT cells (Figure S5H).

Because of the in vitro proliferative defect in DKI cells (Figure 5C), we next evaluated homeostatic proliferation of CD8+ T cells after transfer into Rag2−/− lymphopenic hosts. In both spleen and lymph nodes, we found decreased cell division and lower accumulation of adoptively transferred DKI cells than WT T cells (Figure 5G); this was due to defective expansion of CD8+ T cells (Figure 5G). We also evaluated the ability of adoptively transferred WT or DKI cells to compete with re-populating endogenous cells in sublethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice. CFSE dilution was again slower in the DKI cells (upper half, Figure 5H) and repopulation of total T cells and CD8+ T cells was even more defective, with a suggestion of a CD4+ T cell defect in lymph nodes as well (lower half, Figure 5H). These results together underscore a critical role of STAT5 tetramers for CD8+ T cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in vivo.

STAT5 tetramers are required for normal LCMV-induced CD8+ T-cell expansion

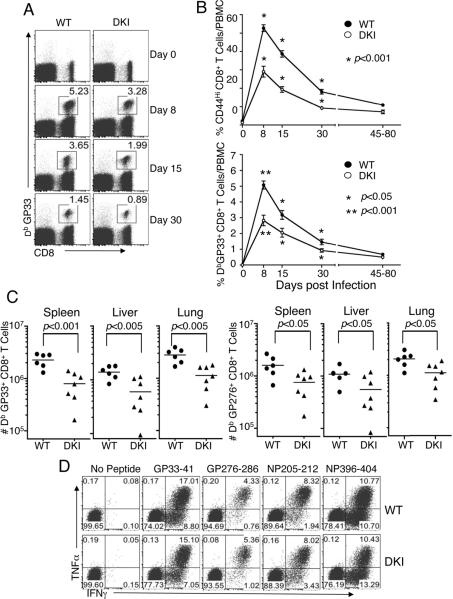

Having found key roles for STAT5 tetramers in CD8+ T cell proliferation, we next used LCMV (Armstrong strain) infection to investigate the CD8+ T-cell activation program in vivo (Kaech et al., 2002), evaluating early and late CD8+ T cell responses (days 8, 15, 30, 45, and 80). Both the frequency (Figure 6A and 6B) of CD44hi activated (Figure 6B, upper panel) and virus-specific (DbGP33+) (lower panel) CD8+ T cells were lower in DKI than in WT mice, especially early after infection, indicating that STAT5 tetramers are more important for the early CD8+ T cell activation and expansion phases than for the late memory development and maintenance phases. In addition, the number of LCMV-specific (DbGP33+ and DbGP276+) CD8+ T cells in lymphoid (spleen) and non-lymphoid (liver and lung) tissues of DKI mice were significantly lower than in WT mice at day 8 (Figure 6C). Despite this difference in the number of CD8+ T cells, both WT and DKI CD8+ T cells produced similar levels of TNFα and IFNγ in response to multiple LCMV epitopes (Figure 6D), indicating that STAT5 tetramers regulate their expansion but have little or no effect on their function. Similarly, DKI mice vaccinated with recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 encoding LCMV glycoprotein had fewer total and CD44hi activated (Figure S6A), as well as antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (Figure S6B). Thus, STAT5 tetramers are required for antigen-specific expansion of activated CD8+ T cells in two different in vivo viral model systems.

Figure 6. Significantly decreased virus-specific CD8+ T cell expansion in STAT5 DKI mice after acute LCMV infection.

(A) Representative FACS profiles. Gating was on total lymphocytes. Shown is the frequency of GP33+ CD8+ T cells in WT and DKI mice at indicated times after infection. (B) The frequency of CD44hi and LCMV GP33-specific CD8+ T cells in blood was analyzed by flow cytometry. The experiment was repeated twice and data pooled (error bars are SEM, with n = 14–18 for each group and at each time point). (C) The total number of GP33+ and GP276+ CD8+ T cells in spleen, liver, and lung was quantified by tetramer staining 8 days post infection. (D) TNFα and IFNγ production in virus-specific CD8+ T cells at day 8 post infection. FACS profiles of intracellular cytokine staining in CD8+ T cells are representative of 7 independent analyses performed after restimulation with the indicated LCMV peptides.

STAT5 tetramers are required for Treg cell suppression in a colitis model

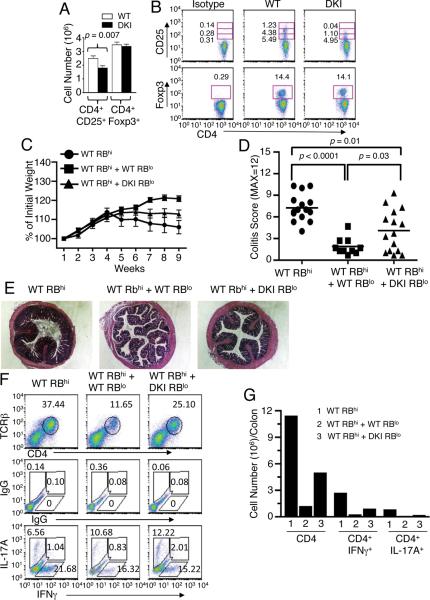

IL-2Rα expression is critical for development of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells and IL-2 promotes the expansion, maintenance, and immunosuppressive function of these cells in vivo (Campbell and Koch, 2011). As shown above, STAT5 tetramer formation is vital for IL-2-induced IL-2Rα expression, and indeed, there were fewer CD4+CD25+ T cells in DKI spleens (Figure 7A; top row of Figure 7B), but surprisingly, the numbers of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells were similar in WT and DKI spleens (Figure 7A; bottom row of Figure 7B). Strikingly, although the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing low levels of CD25 was similar in STAT5 DKI and WT littermates (4.95% vs. 5.49%), the DKI mice had essentially no CD4+ T cells with the highest expression of CD25 (0.04% vs. 1.23%) (Figure 7B, top row). We therefore investigated Treg cell function using an adoptive transfer colitis model (Powrie et al., 1994). Rag2−/− mice adoptively transferred with WT naïve CD4+ (CD45RBhiCD25−) cells alone stopped gaining weight at week 4, and those co-transferred with DKI Treg (CD45RBloCD25+) cells stopped gaining weight at week 5 post-transfer, whereas mice co-receiving WT Treg cells gained weight up to week 8 (Figure 7C). Correspondingly, the inflammation scores (Figure 7D), inflammatory infiltrates histologically (Figure 7E), and the frequency and number of total CD4+ T cells, CD4+IFNγ+, and CD4+IL-17+ cells (Figure 7F and 7G) in the colons of mice receiving WT Treg cells were lower than in mice receiving DKI Treg cells, showing that DKI Treg cells have defective function in vivo.

Figure 7. Decreased CD4+/CD25+ DKI T cells and Impaired immune suppressive function of DKI Treg cells.

(A and B) CD25 (IL-2Rα) and Foxp3 expression on splenic CD4+ T cells from WT and DKI mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are total cell numbers (A) and FACS profiles (B). The numbers indicate the % of CD4+ cells that were also CD25+ or Foxp3+. CD25 expressing cells are divided in low (bottom boxes), intermediate (middle boxes), and high (top boxes) levels. (C) Weight of mice during colitis development. (D) Colitis scores of H&E stained colon sections from two independent experiments. (E) Representative histological sections of colons with H&E staining. (F and G) Shown are FACS profiles (F) and graph (G) of the frequency and number of lamina propria total TCRβ+CD4+, TCRβ+CD4+IFNγ+, and TCRβ+CD4+IL-17A+ T cells from Rag2−/− mice adoptively transferred with WT RBhi, WTRBhi + WT RBlo, or WT RBhi + DKI RBlo cells.

Discussion

STAT protein dimer formation is necessary for mediating DNA binding and transcription of the target genes (Darnell, 1997), and STAT dimers can additionally oligomerize to form tetramers or higher order complexes via their N-domains, allowing binding to tandemly-linked GAS motifs that have been found in a range of genes, including, for example, those encoding IFNγ, IL-2Rα, perforin, CIS, and GlyCam1 (Hou et al., 2003; John et al., 1996; John et al., 1999; Meyer et al., 1997; Verdier et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1996; Yamamoto et al., 2002), but the relative importance of STAT dimers vs. tetramers heretofore has not been addressed in vivo.

In this study, we identified and mutated key residues required for STAT5 tetramerization and generated Stat5a-Stat5b tetramer-deficient DKI mice. In contrast to the perinatal lethality and severely defective lymphoid development in Stat5a−/−Stat5b−/− mice (Cui et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2006), our results establish that STAT5 tetramers are dispensable for survival of mice and thymic development. Nevertheless, STAT5 tetramers are critical for normal NK cell development and maintaining peripheral CD8+ T cell and CD4+CD25+ T cell numbers. Despite fairly normal T cell development in DKI mice, DKI T cells had profoundly diminished proliferation to IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 in vitro and decreased survival upon cytokine withdrawal. Moreover, in adoptive transfer experiments, there was a defect in homeostatic proliferation of CD8+ T cells, and correspondingly, there was defective in vivo expansion of antigen-specific DKI CD8+ T cells following LCMV or Ad5 infection, although memory CD8+ T cell development was similar in WT and DKI mice. We also found that STAT5 tetramers were required for IL-2-induced IL-2Rα expression. The frequency and number of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells were similar in DKI and WT mice, but the DKI Treg cells could not efficiently suppress the development of colitis. Collectively, these data establish a critical role of STAT5 tetramers in CD8+ T cell and CD4+ Treg cell biology.

We also defined binding motifs for STAT5A and STAT5B dimers and tetramers and identified the genes regulated by dimers and tetramers. STAT5A and STAT5B tetramers bind to divergent motifs with an optimal spacing of 11–12 between GAS or GAS-like motifs, but with secondary optimal spacing of 6–7 and 15–17, indicating that STAT5 tetramers can bind to sequences with a very broad range of spacing between tandem GAS motifs, presumably facilitated by the long linker region between the N-domain and DNA binding domain of STAT5 proteins (Leonard and O'Shea, 1998). Intriguingly, the preferred spacings result in two tandemly-linked GAS or GAS-like motifs being separated by approximately half a helical turn. It will be interesting to investigate if the spacing and motif rules for STAT5 also apply to other STAT proteins that can bind as tetramers. In this regard, in the c-fos promoter, STAT1 was observed to preferentially bind to tandemly-linked GAS motifs with a spacing of 5, 10, and 15 nucleotides (Vinkemeier et al., 1996), although genome-wide STAT1 tetramer sites are unknown. Given that GAS motifs are semi-panlindromic 9 bp sequences, which are slightly under a full helical turn in length, rotating a STAT5 dimer approximately half a helical turn along DNA could potentially reconstitute the same topological orientation to allow the N-domain interaction between two dimers, an area for further investigation.

Although STAT5A and STAT5B recognize nearly identical dimer and tetramer motifs, STAT5B tetramers appeared to be more important than STAT5A tetramers in regulating IL-2-induced gene expression, suggesting distinctive as well as overlapping functions for these closely related transcription factors. Although the STAT4 N-domain is required for cytokine-induced activation (Ota et al., 2004), tetramer-deficient mutants of STAT5A and STAT5B can still bind as dimers and drive expression of many genes. The critical role of STAT5 tetramers is underscored by our identification of a range of genes whose induction is abrogated or markedly decreased in the DKI T cells, including Lta, Il24, Socs2, Cdk6, and Bcl2, many of which were not known to be IL-2/STAT5 target genes. Recently, STAT5 tetramers were suggested to mediate repression of the Ig κ gene and other loci in pro-B cells, and it was further suggested that repression might be a preferential role for STAT5 tetramers (Mandal et al., 2011); however, our data indicate that STAT5 tetramers are preferentially associated with gene activation in T cells. The DKI mice we have generated will be valuable for clarifying the roles of STAT5 tetramers in other lineages as well, including B cells.

Our studies also have implications for other STAT proteins that can form tetramers. For example, analogous to STAT5, dimers and tetramers of STAT1 may also differentially control gene expression. Interestingly, multiple STAT5 binding sites, as identified by ChIP-Seq analysis, are often located in 5', proximal promoter, or intronic regulatory regions of STAT5 target genes. This raises the possibility that N-domain mediated tetramerization or higher order oligomerization of STAT5 could be a mechanism by which widely separated STAT5 binding sites could be juxtaposed to the regulatory regions by DNA looping to cooperatively control transcription, an area that warrants investigation. Beyond STAT proteins, it is well known that a range of eukaryotic transcription factors bind to semi-palindromic DNA sequences as dimers, but it is unknown whether they, like STAT proteins, can additionally form tetramers to bind to tandem lower affinity sites. If tetramerization of such other factor(s) indeed occurs, the lessons we have learned from STAT5 could be applicable.

The activation of STAT family proteins by cytokines and growth factors is vital in a broad range of innate and adaptive immune responses and inflammation (Leonard and O'Shea, 1998), and the dysregulation of STAT3 and STAT5 is associated with tumorigenesis (Bromberg et al., 1999; Chiarle et al., 2005; Kelly et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2009). The DKI mice we have generated will allow further evaluation of the roles of STAT5 tetramers in a range of pathological states. Our findings that the absence of tetramerization does not compromise viability and that only a minority of IL-2-modulated genes is regulated by STAT5 tetramers together suggest that selectively targeting tetramer formation will modulate only part of the actions of a cytokine or growth factor, potentially allowing the development of a new therapeutic approach to modulating immune responses, controlling inflammation, and inhibiting tumor growth.

Experimental Procedures

Detailed procedures for cell isolation and culture, plasmid constructs, mutagenesis, nuclear extract preparation, EMSAs, knock-in mouse generation, western blotting, RTPCR, FACS analysis, in vitro proliferation and cell survival, adoptive transfer experiments, Affymetrix GeneChip analysis, ChIP-Seq, RNA-Seq, induction of colitis in Rag2 KO mice, and Ad5 infection experiments are described in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Mice

All protocols were approved by the NHLBI Animal Care and Use Committee and followed NIH guidelines for using animals in intramural research. 6–12 week old gender matched mice were used.

Affymetrix GeneChip data analysis

Affymetrix GCOS version 1.4 was used to calculate the signal intensity and percent present calls. Signal intensity values were transformed using an adaptive variance-stabilizing, quantile-normalizing transformation termed “S10” (Munson, P.J., GeneLogic Workshop of Low Level Analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip Data, 2001; http://abs.cit.nih.gov/geneexpression.html.) and subjected to a principal component analysis (PCA) to detect outliers. One-way ANOVA with eight levels was applied to the transformed data and the Student's t-test was used to compare WT and DKI samples. Genes were selected with 1.5 fold change (FC) at a false discovery rate (FDR) of <20%. Analysis was performed using the JMP statistical software package (www.jmp.com, Cary, NC).

RNA-Seq data analysis

Sequence reads (single end 36 bp) were aligned against the RefSeq mouse gene database (mm8) using ELAND pipeline. Raw counts that fell on exons of each gene were calculated. Genes that were differentially expressed were identified with the statistical R package edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010). Genes were identified as differentially expressed if adjusted p value < 1e-5 and fold-change > 1.5. The expression heatmaps were generated using the gplots package in R.

STAT5A and STAT5B DNA binding motif discovery

Using Model-based Analysis for ChIP-Seq (MACS) (Zhang et al., 2008) to identify statistically significant ChIP-Seq peaks, we compared STAT5A and STAT5B data from WT and Stat5a-Stat5b DKI IgG controls and normalized tag counts based on the total ChIP-Seq tag count for each sample. Peaks were identified using MACS (see Supplemental Methods) and data sets and MACS results summarized in Table S4. Within the peaks, STAT5A and STAT5B binding sites were localized to a small region based on the highest fragment pileup, referred as the “summit” in MACS. We used Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation (MEME) (Bailey and Elkan, 1994) to “de novo” discover consensus motifs from the selected binding sites. Because of the computational complexity in MEME algorithms, we chose the top 10% (with lowest p-value) of IL-2 induced STAT5A-STAT5B binding sites in WT cells to define a consensus motif from a position specific probability matrix (PSPM) that show observed frequencies of each base at each position. The selected sequences were scanned using PSPM and those with scores greater than a given threshold were retained (Figure S5F and S5G). Assuming at most one mismatch from the GAS consensus, the threshold is the total score in all positions minus the highest score at an individual position. Similarly, for two mismatches, the threshold is the total score minus the two highest individual scores. In this fashion, 70 bp sequences containing GAS and/or GAS-like motifs were identified, and these motifs were centered within each sequence (Figure S5H). We normalized the total number of tags for WT and DKI data and compared the number of STAT5A and STAT5B ChIP-Seq tags in the 70 bp regions. We defined sites as candidates for tetrameric binding if the tag numbers in WT at a given location were >10 and the WT:DKI tag ratio was >1.5. Because MEME cannot detect tandemly-linked “gap-based” motifs, to discover STAT5 tetramer motifs, we first identified a GAS or GAS-like motif involved in tetramer binding, then “ignored” it, and then used MEME to search for a second motif within 35 bp on each side of the summit and determined the distance between the centered and second motifs.

Virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses

Mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 105 pfu of LCMV Armstrong strain (Wherry et al., 2003). Lymphocytes were isolated from spleen, liver, lung, and peripheral blood (Barber et al., 2006). MHC class I tetramers conjugated with APC were generated, and surface and intracellular cytokine staining was performed as described (Wherry et al., 2003). Cells were analyzed using an LSR II flow cytometer and FlowJo v.8.8 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Dead cells were removed by gating on Live/Dead Near IR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Inflammation score and cytokine production in LPMCs

At the end-point of the study (9 weeks after adoptive transfer), colonic inflammation was assessed by a modification of scoring systems (Jenkins et al., 1997) in which H&E stained cross-sections of colons are graded for crypt architecture abnormalities such as shortening and distortion (0–3), lamina propria cellularity (0–3), and epithelial abnormalities such as goblet cell loss, epithelial hyperplasia, erosions and ulceration (0–3). Changes were also scored as to the % area of involvement according to the scale 1=25%, 2=50%, and 3=75–100%.

Lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 50 ng/ml PMA, 500 ng/ml calcium ionophore, and 1 μg/ml GolgiStop (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 5 hr before staining with fluorescent-labeled antibodies to TCRβ, CD4, IFNγ, and IL-17A and flow cytometer analysis using FlowJo software.

Statistical analysis

Statistics was performed using Prism4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. N Raghavachari (NHLBI) for Affymetrix Chip assay, Drs. R Spolski (NHLBI), RH Schwartz K–T Jeang (NIAID), K Zhao (NHLBI), and PJ Munson (CIT) for critical comments, Dr. PJ Munson (CIT) for his input in Affymetrix analysis, Drs. J Chen (Hematology Branch), R Spolski, W Liao, and Ms. C Robinson for experimental help, other members in the Leonard Lab for suggestions, and Ms. C Robinson for maintaining the mouse colony. We thank Drs. Carl Wu, Sankar Adhya, and Stoney Simmons for valuable discussions. This work was supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, NHLBI, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession Numbers. The data discussedin this publication are accessible through GEO SuperSeries accession number GSE36890 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cg?acc=GSE36890).

References

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, Darnell JE., Jr. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DJ, Koch MA. Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11:119–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Bhandari R, Vinkemeier U, Van Den Akker F, Darnell JE, Jr., Kuriyan J. A reinterpretation of the dimerization interface of the N-terminal domains of STATs. Protein Sci. 2003;12:361–365. doi: 10.1110/ps.0218903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarle R, Simmons WJ, Cai H, Dhall G, Zamo A, Raz R, Karras JG, Levy DE, Inghirami G. Stat3 is required for ALK-mediated lymphomagenesis and provides a possible therapeutic target. Nat Med. 2005;11:623–629. doi: 10.1038/nm1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Schindler C, Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE, Jr., Mui AL, Miyajima A, Quelle FW, Ihle JN, et al. Distribution of the mammalian Stat gene family in mouse chromosomes. Genomics. 1995;29:225–228. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Riedlinger G, Miyoshi K, Tang W, Li C, Deng CX, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Inactivation of Stat5 in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy reveals distinct functions in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8037–8047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8037-8047.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JE., Jr. STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, Srivastava S, Mistry MJ, Herbst MP, Bailey JP, Horseman ND. Two tandemly linked interferon-gamma-activated sequence elements in the promoter of glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule 1 gene synergistically respond to prolactin in mouse mammary epithelial cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1910–1920. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imada K, Bloom ET, Nakajima H, Horvath-Arcidiacono JA, Udy GB, Davey HW, Leonard WJ. Stat5b is essential for natural killer cell-mediated proliferation and cytolytic activity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2067–2074. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D, Balsitis M, Gallivan S, Dixon MF, Gilmour HM, Shepherd NA, Theodossi A, Williams GT. Guidelines for the initial biopsy diagnosis of suspected chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. The British Society of Gastroenterology Initiative. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:93–105. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Robbins CM, Leonard WJ. An IL-2 response element in the human IL-2 receptor alpha chain promoter is a composite element that binds Stat5, Elf-1, HMG-I(Y) and a GATA family protein. Embo J. 1996;15:5627–5635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Vinkemeier U, Soldaini E, Darnell JE, Jr., Leonard WJ. The significance of tetramerization in promoter recruitment by Stat5. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1910–1918. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nri778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Spolski R, Kovanen PE, Suzuki T, Bollenbacher J, Pise-Masison CA, Radonovich MF, Lee S, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, et al. Stat5 synergizes with T cell receptor/antigen stimulation in the development of lymphoblastic lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2003;198:79–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HP, Kelly J, Leonard WJ. The basis for IL-2-induced IL-2 receptor alpha chain gene regulation: importance of two widely separated IL-2 response elements. Immunity. 2001;15:159–172. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard WJ, O'Shea JJ. Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Darnell JE., Jr. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JX, Mietz J, Modi WS, John S, Leonard WJ. Cloning of human Stat5B. Reconstitution of interleukin-2-induced Stat5A and Stat5B DNA binding activity in COS-7 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10738–10744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Robinson GW, Wagner KU, Garrett L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hennighausen L. Stat5a is mandatory for adult mammary gland development and lactogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:179–186. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Powers SE, Maienschein-Cline M, Bartom ET, Hamel KM, Kee BL, Dinner AR, Clark MR. Epigenetic repression of the Igk locus by STAT5-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1212–1220. doi: 10.1038/ni.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer WK, Reichenbach P, Schindler U, Soldaini E, Nabholz M. Interaction of STAT5 dimers on two low affinity binding sites mediates interleukin 2 (IL-2) stimulation of IL-2 receptor alpha gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31821–31828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriggl R, Topham DJ, Teglund S, Sexl V, McKay C, Wang D, Hoffmeyer A, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, Bunting KD, et al. Stat5 is required for IL-2-induced cell cycle progression of peripheral T cells. Immunity. 1999;10:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Liu XW, Wynshaw-Boris A, Rosenthal LA, Imada K, Finbloom DS, Hennighausen L, Leonard WJ. An indirect effect of Stat5a in IL-2-induced proliferation: a critical role for Stat5a in IL-2-mediated IL-2 receptor alpha chain induction. Immunity. 1997;7:691–701. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota N, Brett TJ, Murphy TL, Fremont DH, Murphy KM. N-domain-dependent nonphosphorylated STAT4 dimers required for cytokine-driven activation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:208–215. doi: 10.1038/ni1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Menon S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–562. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat Rev Immuno. 2009;19:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolovsky M, Fallon AE, Wang S, Brugnara C, Lodish HF. Fetal anemia and apoptosis of red cell progenitors in Stat5a−/−5b−/− mice: a direct role for Stat5 in Bcl-X(L) induction. Cell. 1999;98:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldaini E, John S, Moro S, Bollenbacher J, Schindler U, Leonard WJ. DNA binding site selection of dimeric and tetrameric Stat5 proteins reveals a large repertoire of divergent tetrameric Stat5a binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:389–401. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.389-401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teglund S, McKay C, Schuetz E, van Deursen JM, Stravopodis D, Wang D, Brown M, Bodner S, Grosveld G, Ihle JN. Stat5a and Stat5b proteins have essential and nonessential, or redundant, roles in cytokine responses. Cell. 1998;93:841–850. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udy GB, Towers RP, Snell RG, Wilkins RJ, Park SH, Ram PA, Waxman DJ, Davey HW. Requirement of STAT5b for sexual dimorphism of body growth rates and liver gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7239–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier F, Rabionet R, Gouilleux F, Beisenherz-Huss C, Varlet P, Muller O, Mayeux P, Lacombe C, Gisselbrecht S, Chretien S. A sequence of the CIS gene promoter interacts preferentially with two associated STAT5A dimers: a distinct biochemical difference between STAT5A and STAT5B. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5852–5860. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkemeier U, Cohen SL, Moarefi I, Chait BT, Kuriyan J, Darnell JE., Jr. DNA binding of in vitro activated Stat1 alpha, Stat1 beta and truncated Stat1: interaction between NH2-terminal domains stabilizes binding of two dimers to tandem DNA sites. Embo J. 1996;15:5616–5626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkemeier U, Moarefi I, Darnell JE, Jr., Kuriyan J. Structure of the amino-terminal protein interaction domain of STAT-4. Science. 1998;279:1048–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. 2003;77:4911–4927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Sun YL, Hoey T. Cooperative DNA binding and sequence-selective recognition conferred by the STAT amino-terminal domain. Science. 1996;273:794–797. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Shibata F, Miyasaka N, Miura O. The human perforin gene is a direct target of STAT4 activated by IL-12 in NK cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1245–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Cui Y, Watford WT, Bream JH, Yamaoka K, Hissong BD, Li D, Durum SK, Jiang Q, Bhandoola A, et al. Stat5a/b are essential for normal lymphoid development and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1000–1005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507350103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nussbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.