Abstract

Background

Intravenous (i.v.) iron can improve anaemia of chronic disease and response to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), but data on its use in practice and without ESAs are limited. This study evaluated effectiveness and tolerability of ferric carboxymaltose (FCM) in routine treatment of anaemic cancer patients.

Patients and methods

Of 639 patients enrolled in 68 haematology/oncology practices in Germany, 619 received FCM at the oncologist's discretion, 420 had eligible baseline haemoglobin (Hb) measurements, and 364 at least one follow-up Hb measurement. Data of transfused patients were censored from analysis before transfusion.

Results

The median total iron dose was 1000 mg per patient (interquartile range 600–1500 mg). The median Hb increase was comparable in patients receiving FCM alone (1.4 g/dl [0.2–2.3 g/dl; N = 233]) or FCM + ESA (1.6 g/dl [0.7–2.4 g/dl; N = 46]). Patients with baseline Hb up to 11.0 g/dl and serum ferritin up to 500 ng/ml benefited from FCM treatment (stable Hb ≥11.0 g/dl). Also patients with ferritin >500 ng/ml but low transferrin saturation benefited from FCM treatment. FCM was well tolerated, 2.3% of patients reported putative drug-related adverse events.

Conclusions

The substantial Hb increase and stabilisation at 11–12 g/dl in FCM-treated patients suggest a role for i.v. iron alone in anaemia correction in cancer patients.

Keywords: anaemia, cancer-induced anaemia, chemotherapy-induced anaemia, ferric carboxymaltose, intravenous iron, iron deficiency

introduction

Iron deficiency (ID) and anaemia are frequent comorbidities in patients with a variety of cancers, particularly when receiving chemotherapy [1–3]. The negative impact of anaemia on physical performance and anti-tumour therapy is well known [2, 4, 5]. ID, even in the absence of anaemia and other medical conditions, is associated with impaired physical function, weakness and fatigue; symptoms which can be improved with iron supplementation [6–8]. Factors contributing to the development of anaemia in cancer patients include chronic bleeding, nutritional deficiencies, anaemia of chronic disease, myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and metastatic infiltration of the bone marrow [9]. Notably, ID may not only be defined by depleted iron stores (serum ferritin <100 ng/ml, absolute ID) [10], but also by limited mobilisation of iron from adequately filled stores (transferrin saturation [TSAT] <20%, and ferritin ≥100 ng/ml, functional iron deficiency [FID]) [10, 11]; particularly, if ferritin is upregulated by inflammation, which often occurs in tumour patients. Other markers of reduced iron availability include the ferritin index (soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR)/log ferritin) and the haemoglobin content of reticulocytes (CHr) [12].

In medical practice, chemotherapy-induced anaemia is frequently treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) and/or blood transfusions. However, many patients do not respond to ESA treatment, while the addition of intravenous (i.v.) but not oral iron can substantially improve the response to ESAs [13–18]. Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that transfusions and aggressive ESA treatment may increase mortality [19–21]. Therefore, anaemia treatment guidelines aim to prevent transfusions and to minimise ESA dosages [11, 22, 23]. Studies showing that i.v. iron without concomitant ESA therapy can improve Hb levels [12] and reduce transfusion requirements in cancer patients [24, 25] support these goals.

The study reported here aimed to collect data on the effectiveness and tolerability of ferric carboxymaltose (ferinject® [FCM], Vifor Pharma), a non-dextran parenteral iron preparation, in routine treatment of an unselected anaemic and iron-deficient cancer patient population. This observational study provides the first, large database on the use of FCM in an oncological setting. In other therapeutic areas, FCM has already shown its effectiveness in correcting ID anaemia [26–28].

methods

patients and study design

Adult anaemic cancer patients with active malignancy and absolute or functional ID (indicated by laboratory values or symptoms such as fatigue and impaired physical function) who received FCM as i.v. iron treatment in haematology and oncology practices across Germany and provided informed consent were registered to this prospective, non-interventional study. The study was registered at the Association of Research-based Pharmaceutical Companies in Germany (Study no: 27-10-08; http://www.vfa.de) and conducted following Good Clinical Practice criteria and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Total and individual iron doses, dosing frequency, use of ESAs or blood transfusions, and the frequency of study visits were left to the investigator's discretion following their routine practice. The first day of FCM treatment was defined as baseline, and the observation period was scheduled for 12 weeks.

The safety population consisted of all patients who had received at least one FCM dose during the study. The effectiveness population included patients with an available baseline Hb value assessed between 7 days prior and 3 days after the first FCM administration to ensure that Hb levels were independent of iron administration and other influences. Normal Hb (≥12 g/dl [females], ≥13 g/dl [males] [29]), absence of active malignancy, or age <18 years at inclusion were considered major protocol deviations, and respective patients were excluded from the effectiveness population.

clinical parameters

At baseline, sex, age, body mass index, Karnofsky score, tumour history, anti-tumour treatment, time from diagnosis, and any anaemia treatment in the 4 weeks prior study inclusion were recorded. Serum levels of Hb, TSAT, ferritin, transferrin, sTfR, iron and C-reactive protein, haematocrit, whole blood count, CHr, and hypochromic erythrocytes were recorded at baseline and throughout the study. Due to the observational character of the study, not all parameters were available for all individual patients. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were recorded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria coding dictionary version 3.0.

objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate the Hb increase from baseline to the end of the study (EOS) or termination visit. Secondary objectives included the evaluation of absolute Hb as well as changes in Hb and iron status parameters from baseline to all study weeks, the proportion of patients receiving blood transfusions and/or ESAs during the study period, and the safety of FCM (frequency and severity of ADRs).

statistical analysis

The dependent t-test for paired samples was used for analyses of differences over time, independent two sample t-test for group comparisons, and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics comprised median, upper (Q3) and lower (Q1) quartiles, and mean ± standard deviation. Data are presented as median values (Q1 and Q3) unless otherwise stated.

As final visits often occurred later than 12 weeks after baseline, visits during weeks 12–14 were accounted for the EOS data point. If multiple visits were recorded during weeks 12–14, only data from the visit closest to week 12 were used for analysis. If EOS data were missing, the last data collected during weeks 4–11 were used and defined as termination visit.

Data collected during a study visit were assigned to a particular study week with a tolerance of ±3 days (e.g. measurements obtained during days 4–10 post-baseline were recorded under week 1). When several test results were available from a particular week, results closest to the predetermined day (i.e. day 7, day 14, day 21 etc.) post-baseline were used. Outliers were identified by Grubb's test and considered as missing if no plausible explanation for the deviation was available. No outliers were recorded for Hb, ferritin, and TSAT.

The administration of blood transfusions was recorded in 4-week periods. The Hb levels and iron status parameters of patients who received a transfusion were censored from analysis from the first day of the 4-week period when the transfusion was given.

results

patient characteristics

A total of 639 adult cancer patients were registered in 68 centres between December 2008 and October 2010. Of those, 619 had received at least one FCM dose and were included in the safety population (Supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The effectiveness population comprised 420 patients with a valid baseline Hb measurement, no major protocol deviations, and a median observation period of 11.0 (9.7–11.6) weeks. The median age in this population was 67 (58–73) years, and 45.2% were male (Table 1). The majority (91.2%, N = 383) presented with solid tumours, and of those, 61.0% (N = 256) had metastatic disease. Most patients received cytotoxic chemotherapy (74.3%), and 72 (17.1%) patients were not on anti-cancer treatment at study start. Patients who received concomitant FCM and ESA treatment (17.4%, N = 73) were more often on chemotherapy (84.9% versus 72.9%, P = 0.04) or had advanced disease (71.2% versus 58.8%, P < 0.07).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics (demographics and disease characteristics)

| Safety population (n = 619) | Effectiveness population (n = 420) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 272 (43.9) | 190 (45.2) |

| Age (years, median [Q1–Q3]) | 66 (57–73) | 67 (58–73) |

| Median Karnofsky score | 90 (80–90) | 90 (80–90) |

| Cancer typea, n (%) | ||

| Breast | 133 (21.2) | 106 (25.2) |

| Gastrointestinal | 232 (37.5) | 155 (36.9) |

| Colorectal | 130 (21.0) | 84 (20.0) |

| Gastric | 65 (10.5) | 43 (10.2) |

| Pancreatic | 36 (5.8) | 27 (6.4) |

| Intestinal | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Haematological | 54 (8.7) | 37 (8.8) |

| Lung | 37 (6.0) | 24 (5.7) |

| Gynaecological | 36 (5.8) | 25 (6.0) |

| Prostate | 34 (5.5) | 25 (6.0) |

| Urogenital | 20 (3.2) | 12 (2.9) |

| Other | 73 (11.8) | 36 (8.6) |

| Solid tumours | 565 (91.3) | 383 (91.2) |

| Metastasised | 363 (58.6) | 256 (61.0) |

| Cancer therapy (%)b | ||

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | 424 (68.5) | 312 (74.3) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 60 (9.7) | 47 (11.2) |

| Hormone therapy | 39 (6.3) | 24 (5.7) |

| Radiotherapy | 15 (2.4) | 10 (2.4) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | 17 (2.7) | 8 (1.9) |

| Other therapy | 52 (8.4) | 34 (8.1) |

| (Neo)adjuvant therapy | 125 (20.2) | 93 (22.1) |

| First-line therapy | 186 (30.0) | 127 (30.2) |

| Second—fifth-line therapy | 173 (27.9) | 128 (30.5) |

| No current therapy | 135 (21.8) | 72 (17.1) |

| Prior anti-anaemia therapy (%) | ||

| At least one during the 4 weeks before study begin | 143 (23.1) | 102 (24.3) |

| Transfusion | 78 (12.6) | 55 (13.1) |

| ESA | 42 (6.8) | 35 (8.3) |

| Iron (i.v., p.o.) | 29 (4.7) | 17 (4.0) |

In the safety population, some patients had no tumour type recorded (e.g. anaemia or von Willebrand disease).

aSome patients had more than one tumour entity.

bMultiple treatments possible.

ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; i.v., intravenous; p.o., per os.

Baseline haematological parameters (Table 2) were typical for a cancer patient population. Iron status parameters were assessed in 74% (serum ferritin) and 54% (TSAT) of patients. Within the 4 weeks before study inclusion, 24.3% had received at least one anti-anaemic pre-treatment, most commonly blood transfusions (13.1%) followed by ESAs (8.3%). During the study, the majority of patients (347 [83%]) received FCM without an additional ESA.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics (haematological parameters)

| Effectiveness population (n = 420) |

||

|---|---|---|

| n | Median (Q1–Q3) | |

| Hb (g/dl) | 420 | 10.0 (9.1–10.6) |

| Thrombocytes (×10³/µl) | 417 | 230 (131–318) |

| Leukocytes (×10³/µl) | 411 | 5.7 (3.9–7.4) |

| Erythrocytes (×103/µl) | 408 | 3.5 (3.2–4.0) |

| Haematocrit (%) | 397 | 30.6 (28.1–33.0) |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 312 | 188 (32–509) |

| Serum iron (µg/dl) | 274 | 33.8 (25.7–51.0) |

| Transferrin (mg/dl) | 247 | 210 (171–258) |

| TSAT (%) | 225 | 12.1 (7.7–18.7) |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 210 | 1.3 (0.5–4.6) |

| Reticulocytes (%) | 114 | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) |

| sTfR (mg/l) | 58 | 2.5 (1.9–4.3) |

| CHr (pg) | 37 | 29.2 (26.0–30.6) |

Hb, haemoglobin; TSAT, transferrin saturation; CRP, C-reactive protein; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; CHr, haemoglobin content of reticulocytes.

After censoring for transfusions, data from 328 patients could be analysed for baseline Hb and iron status parameters. The median baseline levels of Hb, ferritin, and TSAT were 10.0 (9.3–10.6) g/dl, 169 (27–480) ng/ml, and 12.2% (7.9%–18.2%), respectively. Patients who received an ESA during the study had lower baseline Hb (9.6 versus 10.0 g/dl; P = 0.009) compared with those treated with FCM alone. Baseline TSAT was higher (16.8% versus 11.0%; P = 0.004) but still below recommendations for ESA-treated patients.

effectiveness

The median Hb increase versus baseline ranged from 1.4 to 1.6 g/dl (Table 3) and was statistically significant in all groups (P < 0.0001). Hb increases in FCM-treated patients receiving or not receiving additional ESAs were not substantially different. Only minor differences in baseline Hb or Hb increase were seen between data censored for transfusions (‘All, censored’) versus uncensored data (‘All, uncensored’). The Hb increase was also comparable for patients who received no or at least one anti-anaemia pre-treatment such as transfusion, ESA, or iron (1.4 [0.3–2.3] versus 1.2 [0–2.4] g/dl; uncensored effectiveness population).

Table 3.

Baseline Hb and increase in Hb from baseline until end of the study or termination visit

| All, uncensored | All, censoreda | FCM onlya | FCM + ESAa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Hb (g/dl) | ||||

| Patients (n) | 420 | 328 | 277 | 51 |

| Mean Hb ± SD | 9.9 ± 1.1 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 10.1 ± 1.0 | 9.6 ± 1.1 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 10.0 (9.1–10.6) | 10.0 (9.3–10.6) | 10.0 (9.4–10.7) | 9.6 (8.9–10.4) |

| Hb increase (g/dl)b,c | ||||

| Patients (n) | 364 | 279 | 233 | 46 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.5 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.4 (0.2–2.3) | 1.4 (0.3–2.3) | 1.4 (0.2–2.3) | 1.6 (0.7–2.4) |

| Baseline ferritin (ng/ml) | ||||

| Patients (n) | 312 | 246 | 204 | 42 |

| Mean ferritin ± SD | 399 ± 566 | 356 ± 500 | 334 ± 500 | 461 ± 491 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 188 (32–509) | 169 (27–480) | 150 (21–444) | 309 (102–645) |

| Ferritin increase (ng/ml)b | ||||

| Patients (n) | 193 | 150 | 125 | 25 |

| Mean ± SD | 581 ± 1077 | 585 ± 1148 | 481 ± 675 | 1105 ± 2344 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 306 (64–767) | 302 (57–767) | 291 (46–711) | 386 (213–839) |

| Baseline TSAT (%) | ||||

| Patients (n) | 225 | 170 | 140 | 30 |

| Mean TSAT ± SD | 18.0 ± 20.3 | 17.3 ± 19.8 | 15.3 ± 16.4 | 26.8 ± 29.9 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 12.1 (7.7–18.7) | 12.2 (7.9–18.2) | 11.0 (7.5–16.8) | 16.8 (11.6–24.7) |

| TSAT increase (%)b | ||||

| Patients (n) | 128 | 94 | 74 | 20 |

| Mean ± SD | 11.0 ± 26.9 | 10.8 ± 22.3 | 14.0 ± 20.2 | −1.0 ± 26.3 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 9.9 (1.4–20.1) | 9.9 (1.4–19.9) | 10.8 (3.0–20.5) | 0.9 (−8.3–5.5) |

aData from patients who received blood transfusions were censored from analysis before the transfusion. bOnly patients who had Hb data available from baseline and at least one follow-up visit during week 4 to end of the study were included.

cP for Hb increase <0.0001 in all groups.

SD, standard deviation; Q1, lower quartile; Q3, upper quartile; Hb, haemoglobin; FCM, ferric carboxymaltose; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

The median total iron dose per patient was 1000 (600–1500) mg and comparable for patients that had been treated with FCM only (1000 [600–1400] mg) or concomitantly with an ESA (1000 [700–1500] mg). Median Hb differences were comparable in subpopulations stratified by the total iron dose and infusion frequency (range 1.3–1.8 g/dl). Heterogeneity of the subpopulations did not allow for a more detailed statistical analysis or interpretation.

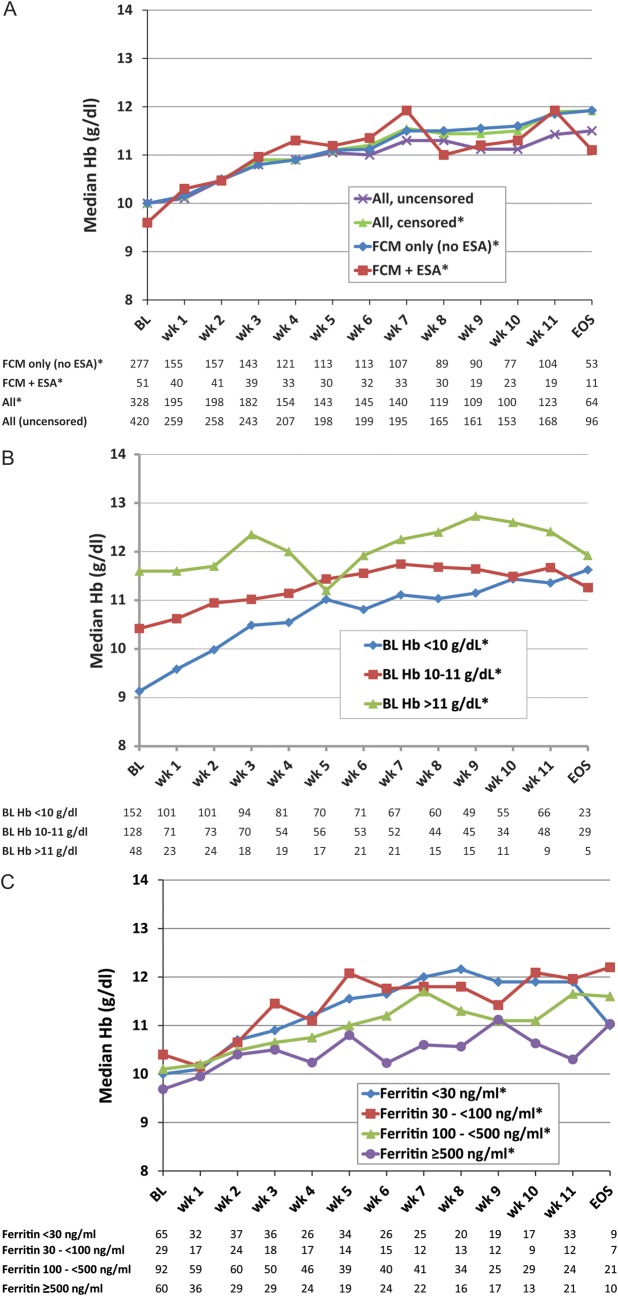

Hb levels improved steadily after the first FCM administration until the EOS (Figure 1A–C). From week 5 onwards, median Hb levels remained stable in the range of 11–12 g/dl and were comparable between patients treated with FCM alone and those also receiving an ESA (Figure 1A). Increase in median Hb levels was more pronounced in patients with moderate-to-severe anaemia (baseline Hb <10 g/dl) than in those with mild anaemia (baseline Hb 10–11 g/dl). Thus, both groups had achieved similar median Hb levels by the EOS (Figure 1B). Overall, 64% of patients achieved final Hb levels ≥11 g/dl and 38% achieved Hb levels ≥12 g/dl.

Figure 1.

Median Hb levels over the course of the study period and stratified by different patient characteristics. *Data were censored for transfusion use. (A) Median Hb stratified by concurrent ESA use and censorship of data following a blood transfusion. (B) Median Hb levels stratified by baseline Hb. (C) Median Hb levels stratified by baseline serum ferritin (cut-offs <30 and ≥100 ng/ml according to thresholds for absolute and functional iron deficiency by NCCN [11]). Hb, haemoglobin; BL, baseline; EOS, end of the study (weeks 12–14); ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent.

Baseline serum ferritin was available in 312 patients. Patients with baseline ferritin levels <100 ng/ml showed a trend to achieve a median Hb ≥11 g/dl earlier (week 4) than those with baseline ferritin ≥100 ng/ml, who achieved Hb ≥11 g/dl by week 6 (Figure 1C).

Patients with the highest baseline ferritin levels (≥500 ng/ml) reached a median Hb of ≥11 g/dl later (9 versus 4–5 weeks), despite receiving a slightly higher median total iron dose per patient (1200 [950–1750] versus 1000 [600–1500] mg) compared with those with ferritin <500 ng/ml. More of these patients had advanced cancers (84% versus 58%, P < 0.001) and received chemotherapy (86% versus 72%, P = 0.01), median Karnofsky score was lower (80 versus 90, P < 0.001), and mean baseline TSAT was higher (28.8% ± 27.5% versus 14.2% ± 15.2%, P < 0.001). Patients with baseline ferritin levels ≥500 ng/ml who achieved an Hb increase ≥1 g/dl had a lower mean baseline TSAT (20.9% ± 7.0%) than those with an Hb increase <1 g/dl (TSAT 31.8% ± 27.6%). In the overall population, Hb increase was independent of baseline TSAT (cut-off 20%).

Median ferritin levels were elevated at baseline and increased until EOS or termination visit without substantial differences between the investigated groups (Table 3). Median ferritin levels among censored patients raised up to 893 ng/ml (week 3). Patients with available TSAT values presented with low median TSAT at baseline. Notably, median TSAT was very low at baseline (11.0%) but almost doubled (+10.8%) in patients treated with FCM alone. Median TSAT of patients treated with FCM plus ESA was only slightly below normal at baseline (16.8%) and showed only a modest median increase (+0.86%) over the study period.

A total of 119 patients in the effectiveness population (28.3%) received ≥1 transfusion at any time during the study or within 4 weeks before the study (median 3, range 1–22). The proportion of patients receiving their first transfusion after the initiation of FCM decreased from 13.8% during weeks 1–4 to 9.1% after week 4 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of patients receiving blood transfusions before and after the initiation of FCM

| FCM | FCM + ESA | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Four weeks before first FCM dose | 12.1 (347) | 17.8 (73) | 13.1 (420) |

| Weeks 1–4 post first FCM dosea | 11.8 (347) | 23.3 (73) | 13.8 (420) |

| After week 4 post first FCM dosea | 8.2 (306) | 14.3 (56) | 9.1 (362) |

Data shown as % (patients at risk). aPercent patients receiving their first blood transfusion after the initiation of FCM.

FCM, ferric carboxymaltose; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent.

tolerability

A total of 354 (60.2%) patients in the safety population completed the 12-week observation period. Forty-three (7.3%) patients were lost to follow-up, 42 (7.1%) died, and 31 (5.3%) withdrew consent. For 118 (20.1%) patients, no or other reasons for termination were recorded (e.g. some physicians stopped data collection after 6 weeks without recording a reason, if a patient experienced a satisfactory Hb response).

FCM at total iron doses of 600–1500 mg was well tolerated and blood counts (thrombocytes, leukocytes, erythrocytes) were comparable at baseline and EOS. ADRs were recorded for only 14 (2.3%) patients. These were mainly related to the gastrointestinal tract, and only nausea and diarrhoea were reported more than once (Table 5). One allergy/immunology reaction (flush) that was mild and resolved on the day of onset was reported. One possibly related serious adverse drug reaction was recorded for a 66-year-old male patient receiving third-line cytotoxic chemotherapy for a head/neck tumour with pulmonary metastasis and experienced hypoxia resulting in death. The patient received the second iron dose (200 mg, 6 days after the first dose) and died the same day.

Table 5.

Adverse drug reactions reported in the safety population (n = 619)

| ADR | SADR | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of ADRs | ||

| Patients with at least one ADR | 14 (2.3%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Number of ADRs recorded | 20 | 1 |

| Causal relationship with FCM | ||

| Probably | 3 | 0 |

| Possibly | 17 | 1 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Nausea | 6 | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 3 | 0 |

| Hypoxia | 1 | 1 |

| Constipation, obstruction, dry mouth, flush, rigors/chills, dizziness, musculoskeletal pain, thromboembolism | 1 each | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 0 |

ADRs were classified using the Common Terminology Criteria coding dictionary.

ADR, adverse drug reaction; SADR, serious adverse drug reaction; FCM, ferric carboxymaltose.

In a survey evaluating the satisfaction with FCM, a ‘very good’ or ‘good’ rating for efficacy and for tolerability was given by 97.4% and 81.0% of 390 responding investigators. Furthermore, 81.5% planned to use FCM again in these patients, if required.

discussion

This is the first published dataset that documents the use and outcomes of FCM treatment in cancer patients and complements available data in patients with chronic kidney disease [27, 30], inflammatory bowel disease [28, 31], chronic heart failure [32], preoperative anaemia correction [33], and heavy menstrual bleeding [34] or postpartum anaemia [35, 36]. In addition, this study, although of observational nature, presents the largest subset of data on cancer patients treated with i.v. iron as the primary anti-anaemia therapy.

Overall, median Hb levels of anaemic cancer patients receiving FCM treatment in routine clinical practice improved and stabilised >11 g/dl within 5 weeks of the first FCM administration. The extent of the final improvement in Hb was comparable in patient groups stratified by concomitant ESA use and different baseline characteristics such as Hb or serum ferritin levels. Detailed analysis of the Hb increase did not reveal an effect of anti-anaemia pre-treatments (e.g. ESAs or blood transfusions) on the study results. Most important, the effectiveness of FCM without an additional ESA in this large cancer patient population confirms former results of clinical studies showing higher Hb levels [12] and less transfusion requirements in cancer patients with i.v. iron as sole anaemia therapy [24, 25].

As expected, Hb increase was higher in patients with low initial Hb levels (<10 versus ≥10 g/dl), although they needed slightly longer to achieve sustained levels >11 g/dl. In more than one-third of patients, Hb levels remained <11 g/dl, suggesting that regular monitoring of the Hb status, ongoing (maintenance) anaemia treatment, and possibly addition of an ESA is required. Notably, median Hb levels remained stable between 11 and 13 g/dl in the group of patients who had already Hb levels >11 g/dl at baseline. These findings seem to confirm that i.v. iron has no major influence on the regulation of erythropoiesis and suggest that there is no risk of increasing Hb levels beyond recommended ranges as seen with ESAs and reflected in ESA dosing recommendations [11, 23].

Since patients with baseline serum ferritin levels <100 ng/ml achieved a more rapid Hb increase, low baseline ferritin is a good indicator of depleted iron stores and predicts rapid treatment response. These patients can benefit most from i.v. iron therapy. Furthermore, the observed Hb improvement in patients with low mean baseline TSAT (14.2%) and ferritin baseline levels up to 500 ng/ml confirms that cancer patients can experience a shortage in available iron despite elevated ferritin levels (FID). Accordingly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend the concomitant use of i.v. iron and ESAs in patients with ferritin up to 800 ng/ml, if TSAT is <20% [11]. Patients with FID can particularly benefit from i.v. iron treatment. Currently, only a small proportion of patients with chemotherapy-induced anaemia are treated with iron [37], and the majority of these receive oral iron, although this is less effective in patients with FID and associated with gastrointestinal intolerance and poor compliance [11].

Higher baseline TSAT levels (28.8%) and more advanced disease in patients with serum ferritin >500 ng/ml might be the reason why this subgroup of patients showed a slower response to iron treatment, although they received a higher total dose per patient. Notably, Hb responders in this population had a lower mean baseline TSAT than non-responders. However, the number of patients in this subpopulation is too low to draw conclusions on the predictive role of TSAT in patients with ongoing acute-phase reactions. Observed fluctuations in Hb levels may be a consequence of the small patient numbers in this group.

In general, FCM at total iron doses of 600–1500 mg was well tolerated. ADRs were recorded for only 14 (2.3%) patients, and the mortality and completion rate are in line with a population of cancer patients in which 27.9% were receiving second-line or higher anti-tumour therapy, and 64.2% had metastatic disease. Serum ferritin values increased markedly from baseline to termination visit across all groups without any indications of iron overload or increased adverse reactions.

This observational study provided the opportunity to investigate the use of FCM in a routine clinical setting and documented the choice of diagnostic parameters routinely used for anaemia and iron status assessment. The non-interventional study design allowed for the evaluation of various treatment options as well as a broad range of underlying diseases and concurrent therapies that could affect the effectiveness and tolerability of the treatment.

Due to its observational nature, the study has some limitations, including the absence of a control arm, a less well defined patient population compared with a controlled clinical study, and a low proportion of patients having all critical haematological parameters (i.e. Hb, ferritin, and TSAT) assessed. The latter aspect, although limiting the characterisation of the patient population, illustrates the current uncertainty in selecting appropriate diagnostic parameters for cancer-related anaemia. Accordingly, awareness about iron homeostasis in cancer patients needs to be increased. Notably, the assessment of baseline ferritin and TSAT in 74% and 54% of patients in this study is already an improvement compared with findings of the German Cancer Anaemia Registry (2004–2005) or a survey on the management of chemotherapy-induced anaemia (2009–2010), where baseline ferritin was assessed in only 44% or 47% and TSAT in 33% or 14% of patients [37, 38].

Overall, the results of this observational study and the satisfaction of the physicians with FCM's effectiveness and tolerability suggest a role for i.v. iron alone in the correction of anaemia in cancer patients with ID and provide a rationale for further investigations on this topic.

funding

This work was supported by Vifor Pharma Deutschland GmbH who sponsored the study and supported the development of the study design. Medical writing support and the Oxford Open Access licence for publication were funded by Vifor Pharma Ltd. Interpretation of the data as well as the review and decision to submit the manuscript for publication have been carried out independently by all authors.

disclosures

TS disclosed membership in speaker bureaus and/or advisory boards of Vifor Pharma, Medice, Amgen, Ortho Biotech, and Roche; and conduct of research for Vifor Pharma Ltd., Amgen and Roche. BT disclosed consultancy for Vifor Pharma Ltd. OH and BK are employees of Vifor Pharma Ltd.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all investigators at all participating study sites. Medical writing support was provided by Walter Fürst (SFL Regulatory Affairs & Scientific Communication Ltd., Switzerland). The manuscript was reviewed and commented by Beate Rzychon and Marcel Felder (Vifor Pharma Ltd., Glattbrugg, Switzerland) and Garth Virgin (Vifor Pharma, Munich, Germany).

references

- 1.Beale AL, Penney MD, Allison MC. The prevalence of iron deficiency among patients presenting with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:398–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00789.x. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludwig H, Van Belle S, Barrett-Lee P, et al. The European Cancer Anaemia Survey (ECAS): a large, multinational, prospective survey defining the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2293–2306. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.019. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludwig H, Müldür E, Endler G, et al. High prevalence of iron deficiency across different tumors correlates with anemia, increases during cancer treatment and is associated with poor performance status. Haematologica. 2011;96 409, Abstract 982. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser CM, Millesi W, Kornek GV, et al. Impact of hemoglobin level and use of recombinant erythropoietin on efficacy of preoperative chemoradiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01488-2. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas G. The effect of hemoglobin level on radiotherapy outcomes: the Canadian experience. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:60–65. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownlie T, Utermohlen V, Hinton PS, et al. Tissue iron deficiency without anemia impairs adaptation in endurance capacity after aerobic training in previously untrained women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:437–443. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krayenbuehl PA, Battegay E, Breymann C, et al. Intravenous iron for the treatment of fatigue in nonanemic, premenopausal women with low serum ferritin concentration. Blood. 2011;118:3222–3227. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346304. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-04-346304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdon F, Burnand B, Stubi CL, et al. Iron supplementation for unexplained fatigue in non-anaemic women: double blind randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:1124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1124. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grotto HZ. Anaemia of cancer: an overview of mechanisms involved in its pathogenesis. Med Oncol. 2008;25:12–21. doi: 10.1007/s12032-007-9000-8. doi:10.1007/s12032-007-9000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beguin Y. Prediction of response and other improvements on the limitations of recombinant human erythropoietin therapy in anemic cancer patients. Haematologica. 2002;87:1209–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Inc. NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology; Cancer and Chemotherapy-Induced Anemia–v.2.2012. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/anemia.pdf. (5 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinmetz HT, Tsamaloukas A, Schmitz S, et al. A new concept for the differential diagnosis and therapy of anaemia in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:261–269. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0812-2. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-0812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auerbach M, Ballard H, Trout JR, et al. Intravenous iron optimizes the response to recombinant human erythropoietin in cancer patients with chemotherapy-related anemia: a multicenter, open-label, randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1301–1307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.119. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.08.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auerbach M, Silberstein PT, Webb RT, et al. Darbepoetin alfa 300 or 500 ug once every 3 weeks with or without intravenous iron in patients with chemotherapy-induced anemia. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:655–663. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21779. doi:10.1002/ajh.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastit L, Vandebroek A, Altintas S, et al. Randomized, multicenter, controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of darbepoetin alpha administered every 3 weeks with or without intravenous iron in patients with chemotherapy-induced anemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1611–1618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4620. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedenus M, Nasman P, Liwing J. Economic evaluation in Sweden of epoetin beta with intravenous iron supplementation in anaemic patients with lymphoproliferative malignancies not receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33:365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00924.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry DH, Dahl NV, Auerbach M, et al. Intravenous ferric gluconate significantly improves response to epoetin alfa versus oral iron or no iron in anemic patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2007;12:231–242. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-2-231. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-2-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedrazzoli P, Farris A, Del PS, et al. Randomized trial of intravenous iron supplementation in patients with chemotherapy-related anemia without iron deficiency treated with darbepoetin alpha. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1619–1625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2051. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Brillant C, et al. Erythropoietin or darbepoetin for patients with cancer – meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD007303. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007303.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Blumberg N, et al. Blood transfusions, thrombosis, and mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2377–2381. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2377. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.21.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrijvers D. Management of anemia in cancer patients: transfusions. Oncologist. 2011;16(Suppl 3):12–18. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S3-12. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bokemeyer C, Aapro MS, Courdi A, et al. EORTC guidelines for the use of erythropoietic proteins in anaemic patients with cancer: 2006 update. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.10.014. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzo JD, Brouwers M, Hurley P, et al. American Society of Hematology/American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update on the use of epoetin and darbepoetin in adult patients with cancer. Blood. 2010;116:4045–4059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300541. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-08-300541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dangsuwan P, Manchana T. Blood transfusion reduction with intravenous iron in gynecologic cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:522–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YT, Kim SW, Yoon BS, et al. Effect of intravenously administered iron sucrose on the prevention of anemia in the cervical cancer patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.014. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyseng-Williamson KA, Keating GM. Ferric carboxymaltose: a review of its use in iron-deficiency anaemia. Drugs. 2009;69:739–756. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969060-00007. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qunibi WY. The efficacy and safety of current intravenous iron preparations for the management of iron-deficiency anaemia: a review. Arzneimittelforschung. 2010;60:399–412. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296304. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1296304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evstatiev R, Marteau P, Iqbal T, et al. FERGIcor, a randomized controlled trial on ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:846–853. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.005. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO. Iron deficiency anaemia – assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programme managers. NHD/01.3. 2001.

- 30.Covic A, Mircescu G. The safety and efficacy of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose in anaemic patients undergoing haemodialysis: a multi-centre, open-label, clinical study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2722–2730. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq069. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulnigg S, Stoinov S, Simanenkov V, et al. A novel intravenous iron formulation for treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: the ferric carboxymaltose (FERINJECT) randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1182–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01744.x. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anker SD, Comin CJ, Filippatos G, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2436–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908355. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisbe E, Garcia-Erce JA, Diez-Lobo AI, et al. A multicentre comparative study on the efficacy of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose and iron sucrose for correcting preoperative anaemia in patients undergoing major elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:477–478. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer242. doi:10.1093/bja/aer242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Wyck DB, Mangione A, Morrison J, et al. Large-dose intravenous ferric carboxymaltose injection for iron deficiency anemia in heavy uterine bleeding: a randomized, controlled trial. Transfusion. 2009;49:2719–2728. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02327.x. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Wyck DB, Martens MG, Seid MH, et al. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose compared with oral iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:267–278. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275286.03283.18. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000275286.03283.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seid MH, Derman RJ, Baker JB, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose injection in the treatment of postpartum iron deficiency anemia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:435–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludwig H, Aapro M, Beguin Y, et al. Frequent use of blood transfusions in current treatment practice for chemotherapy-induced anaemia counteracts treatment recommendations aiming for fewer transfusions. Haematologica. 2011;96 407, Abstract 978. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinmetz T, Totzke U, Schweigert M, et al. A prospective observational study of anaemia management in cancer patients – results from the German Cancer Anaemia Registry. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:493–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01230.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.