Abstract

The objectives of this study were to assess the rates of comorbid anxiety disorders other than PTSD in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and axis II comparison subjects over ten years of prospective follow-up and to determine time-to-remission, recurrence, and new onset of these disorders. The SCID I was administered to 290 borderline patients and 72 axis II comparison subjects at baseline and at five contiguous two-year follow-up waves. The rates of anxiety disorders for those in both groups declined significantly over time, although they remained significantly higher among borderline patients. By ten-year follow-up, the rates of remission for borderline patients who met criteria for these disorders at baseline were high, while the rates of recurrences and new onsets were moderate. These results suggest that anxiety disorders are very common over time among borderline patients. They also suggest that these disorders have an intermittent course among those with BPD.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, borderline personality disorder, remission, recurrence, new onset

1. Introduction

Clinical experience suggests that anxiety disorders are common among patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Despite this, only three cross-sectional studies have been published which detail rates of specific anxiety disorders in patients with BPD (Zanarini et al., 1998; McGlashan et al., 2000; Zimmerman & Mattia, 1999). In these studies, rates of panic disorder among borderline patients ranged from 30.5%–47.8% (median=33.7), while rates of agoraphobia ranged from 0.6%–12.1% (median=1.7%). Rates of social phobia ranged from 19.4%–45.9% (median=42.4%) and rates of simple phobia ranged from 20.3%–31.7% (median=26.0%). Rates of OCD ranged from 15.6% to 20.3% (median=16.0%), while rates of GAD ranged from 13.5%–21.7% (median=13.6%).

Longitudinally, the prevalence of anxiety disorders in borderline patients was studied over six years of prospective follow-up in the McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD) (Zanarini et al., 2004). It was found that the prevalence of anxiety disorders among BPD patients and a comparison group of patients with other personality disorders declined significantly over time. Among the borderline patients, the rate of any anxiety disorder was 89.0% at baseline and decreased to 60.2% after six-years of follow-up. In the comparison group of patients with other personality disorders, the rate of any anxiety disorder was 56.9% at baseline and decreased to 23.8% after six-years of follow-up. Though the rates declined among both groups, the prevalence of anxiety disorders remained significantly higher among borderline patients than axis II comparison subjects after six-years of follow-up.

A report from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS) assessed the rates of remission, relapse and new onsets of anxiety disorders in a combined group of axis II patients, including borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive PD patients, over a prospective period of seven years (Ansell et al., 2010). This report found that BPD was associated with an increased risk of relapse for OCD and an increased risk for new onsets of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder.

A report from the Children in the Community Study (CIC), a prospective longitudinal study assessed the risk of developing anxiety disorders in middle adulthood among people who had exhibited personality disorder traits in early adulthood (Johnson et al., 2006). The study found that people without a history of anxiety disorders who evidenced traits of borderline personality disorder in early adulthood were at a higher risk of developing anxiety disorders in middle adulthood.

The current study, which is an extension of the MSAD study mentioned above, is the first longitudinal study to assess the prevalence of anxiety disorders other than PTSD (see Zanarini et al., 2011 Epub ahead of print for results pertaining to PTSD) over 10 years of prospective follow-up in a large and well-defined sample of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. It is also the first study to assess time-to-remission, time-to-recurrence, and time-to-new onset of each of these anxiety disorders in borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects.

2. Method

2.1. Procedures

The methodology of this study has been described in detail elsewhere (Zanarini et al., 2003). Briefly, all subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she: 1) was between the ages of 18–35; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then met with a masters-level interviewer blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough diagnostic assessment. Three semi-structured diagnostic interviews were administered. These diagnostic interviews were: 1) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (Spitzer et al., 1992), 2) the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) (Zanarini et al., 1989) and 3) the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (DIPD-R) (Zanarini et al., 1987). The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of all three of these measures have been found to be good-excellent (Zanarini & Frankenburg, 2001; Zanarini et al., 2002).

At each of five follow-up assessments, separated by 24 months, axis I and II psychopathology was reassessed via interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by different staff members at each follow-up blind to baseline and follow-up diagnoses. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered (with the SCID I focusing on the past two years and not as at baseline, lifetime axis I psychopathology). The follow-up interrater reliability (within one generation of follow-up raters) and follow-up longitudinal reliability (from one generation of raters to the next) of these three measures have also been found to be good-excellent (Zanarini & Frankenburg, 2001; Zanarini et al., 2002).

2.2 Participants

Two hundred and ninety patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for BPD and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one non-borderline axis II disorder (and neither criteria set for BPD). Of these 72 comparison subjects, 4% met DSM-III-R criteria for an odd cluster personality disorder, 33% met DSM-III-R criteria for an anxious cluster personality disorder, 18% met DSM-III-R criteria for a non-borderline dramatic cluster personality disorder, and 53% met DSM-III-R criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which was operationally defined in the DIPD-R as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 Axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

Baseline demographic data have been reported elsewhere (Zanarini et al., 2003). Briefly, 279 participants (77%) were female, and 315 (87%) were white. The mean age of the participants was 27.0 (SD=6.3) years, the mean socioeconomic status was 3.3 (SD=1.5) (range of 1 to 5, with 5 indicating the lowest status) (Hollingshead, 1957), and the mean Global Assessment of Functioning score was 39.8 (SD=7.8) (indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood).

In terms of continuing participation, 275 borderline patients were reinterviewed at 2 years, 269 at 4 years, 264 at 6 years, 255 at 8 years, and 249 at 10 years. In terms of axis II comparison subjects, 67 were reinterviewed at 2 years, 64 at 4 years, 63 at 6 years, 61 at 8 years, and 60 at 10 years. At the 10-year assessment, 41 borderline patients were no longer in the study: 12 had committed suicide, seven died of other causes, nine discontinued their participation, and 13 were lost to follow-up. By this time, 12 axis II subjects were no longer participating in the study: one had committed suicide, four discontinued their participation, and seven were lost to follow-up. Overall, 91.9% of surviving borderline patients (249/271) and 84.5% of surviving axis II comparison subjects (60/71) were evaluated six times (baseline and five follow-up periods).

2.3. Definition of Remissions, Recurrences and New Onsets

We defined remission as any 2-year period (any follow-up period) in which the criteria for an anxiety disorder were no longer met. We chose this length of time at the start of the study to mirror our definitions of remission of BPD and its constituent symptoms (Zanarini et al., 2010). In addition, a recurrence or new onset was defined as any 1-month period during the entire 2-year follow-up in which the criteria for an anxiety disorder were met.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Generalized estimating equations (GEE), with diagnosis and time as main effects, were used in longitudinal analyses of prevalence data. Tests of diagnosis by time interactions were conducted. These analyses modeled the log prevalence and controlled for gender, yielding an adjusted relative risk ratio (RRR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for diagnosis and time. Gender was included in these analyses as a covariate as borderline patients were significantly more likely than axis II comparison subjects to be female. Type I error was set at the α=0.05 level, two-tailed, for the analysis of any anxiety disorder; to control to multiplicity, we set α=0.01 level, two-tailed, for analyses of specific disorders. The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator (of the survival function) was used to assess time-to-remission of anxiety disorders other than PTSD, time-to-recurrence of these disorders, and time-to-new onsets. We defined time-to-remission of each of the anxiety disorders studied as the follow-up period at which a two-year remission was first achieved. Thus, possible values for this time-to-remission measure were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=2 years for persons first achieving a remission of the disorders studied during the first follow-up period, time=4 years for persons first achieving such a remission during the second follow-up period, etc. We defined time-to-new onset in a like manner. We defined time-to-recurrence in a somewhat different manner (i.e., the number of years after a remission had been achieved that recurrence first occurred). Thus, time-to-recurrences were 2, 4, 6, or 8 years after first remission.

3. Results

Table 1 details the prevalence of anxiety disorders reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects over 10 years of prospective follow-up. As can be seen, a significantly higher percentage of borderline patients than axis II comparison subjects reported experiencing any anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, OCD, and GAD. For both borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects, the rates of anxiety disorders, with the exception of OCD and GAD, declined significantly over time. No interaction between diagnosis and time was found to be significant, indicating that the rates of decline were similar for both groups of patients.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders among Borderline Patients and Axis II Comparison Subjects Over Ten Years of Prospective Follow-up

| Borderline Patients | Axis II Comparison Subjects | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (N=290) | 2 Yr FU (N=275) | 4 Yr FU (N=269) | 6 Yr FU (N=264) | 8 Yr FU (N=255) | 10 Yr FU (N=249) | BL (N=72) | 2 Yr FU (N=67) | 4 Yr FU (N=64) | 6 Yr FU (N=63) | 8 Yr FU (N=61) | 10 Yr FU (N=60) | RRR Diagnosis a Time b | 95 % CI Diagnosis Time Interaction | |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 80.3 (N= 233) | 63.6 (N=175) | 57.3 (N=154) | 50.8 (N=134) | 45.9 (N=117) | 37.8 (N= 94) | 48.6 (N= 35) | 32.8 (N=22) | 25.0 (N=16) | 20.6 (N= 13) | 18.3 (N=11) | 18.3 (N=11) | 1.93 0.47 |

1.53, 2.42 0.41, 0.54 |

| Panic Disorder | 45.2 (N=131) | 31.6 (N=87) | 33.5 (N=90) | 29.2 (N=77) | 29.4 (N=75) | 22.9 (N=57) | 20.8 (N=15) | 9.0 (N=6) | 3.1 (N=2) | 11.1 (N=7) | 8.2 (N=5) | 10.0 (N=6) | 3.09 0.57 |

2.09, 4.57 0.46, 0.71 |

| Agoraphobia | 12.1 (N=35) | 2.18 (N=6) | 2.97 (N=8) | 4.55 (N=12) | 3.53 (N=9) | 4.02 (N=10) | 2.78 (N=2) | 1.49 (N=1) | 0.0 (N=0) | 1.59 (N=1) | 0.0 (N=0) | 1.67 (N=0) | 3.70 0.32 |

1.28, 10.7 0.15, 0.71 |

| Social Phobia | 49.7 (N=144) | 22.6 (N=62) | 19.0 (N=51) | 17.4 (N=46) | 11.8 (N=30) | 7.2 (N=18) | 22.2 (N=16) | 6.0 (N=4) | 6.3 (N=4) | 6.4 (N=4) | 0.0 (N=0) | 1.7 (N=1) | 2.58 0.14 |

1.70, 3.92 0.10, 0.21 |

| Simple Phobia | 35.2 (N=102) | 33.8 (N=93) | 23.4 (N=63) | 17.8 (N=47) | 10.2 (N=26) | 10.0 (N=25) | 20.8 (N=15) | 22.4 (N=15) | 18.8 (N=12) | 11.1 (N=7) | 6.56 (N=4) | 5.00 (N=3) | 1.49 0.26 |

1.03, 2.15 0.20, 0.35 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 14.5 (N=42) | 8.0 (N=22) | 9.3 (N=25) | 6.4 (N=17) | 11.0 (N=28) | 10.0 (N=27) | 2.8 (N=2) | 4.5 (N=3) | 1.6 (N=1) | 4.8 (N=3) | 1.6 (N=1) | 1.7 (N=1) | 3.62 0.80 |

1.46, 8.98 0.53, 1.21 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 11.0 (N=32) | 8.7 (N=24) | 6.3 (N=17) | 7.2 (N=19) | 10.2 (N=26) | 4.4 (N=11) | 2.8 (N=2) | 1.5 (N=1) | 0.0 (N=0) | 3.2 (N=2) | 3.3 (N=2) | 1.7 (N=1) | 4.27 0.63 |

1.83, 9.96 0.38, 1.04 |

P-level results for Dx were: any anxiety disorder, <0.001; panic, <0.001; Agor., 0.016; social, <0.001; simple, 0.032; OCD, 0.005; and GAD, 0.001.

P-level results for time were all < 0.001 except ; OCD, NS; GAD, 0.070. Agor, 0.005.

P-level results for interaction were all not significant.

As the relative risk ratios (RRRs) for diagnosis and time in Table 1 contain more fine grained information, we believe that an example would be useful. As can be seen, about 80% of borderline patients (and about 49% of axis II comparison subjects) had a history of any anxiety disorder at the time of their index admission. By the time of their 10-year follow-up, these prevalence rates had declined to about 38% and 18% respectively. The RRR of 1.93 for diagnosis indicates that borderline patients were nearly 2 times more likely to report experiencing any anxiety disorder as axis II comparison subjects. The RRR of 0.47 for time indicates that the chance of experiencing any anxiety disorder over the course of the study for those in both groups decreased by 53% ([1−0.47] × 100%).

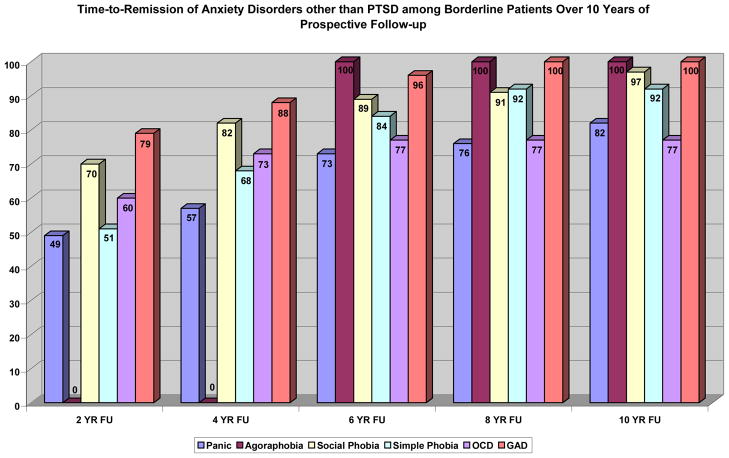

3.1. Remission

Figure 1 details the rates of remission of panic, agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, OCD, and GAD for borderline patients who met criteria for these disorders at baseline. All six disorders had high rates of remission at 10-year of follow-up. The rates of remission for patients who met criteria for anxiety disorders at baseline were as follows: 77% for OCD, 82% for panic disorder, 92% for simple phobia, 97% for social phobia, and 100% for GAD and agoraphobia. (Note that the estimated rates of remission, recurrence, and new onsets presented in Figures 1–3 cannot be directly determined using the numbers presented above and below because of censoring [i.e., subjects lost to follow-up].)

Figure 1.

Figure 3.

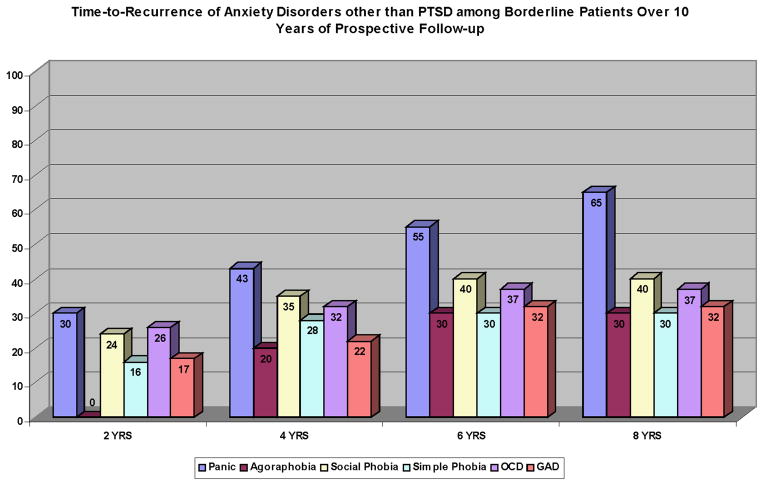

3.2. Recurrence

Figure 2 details the rates of recurrence of panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, OCD, and GAD for borderline patients who met criteria for these disorders at baseline and who experienced a remission of these disorders at an earlier follow-up period. By the time of the 10-year follow-up, 65% of the borderline patients who had remitted from panic disorder and 40% who had remitted from social phobia reported meeting criteria for a recurrence. As can also be seen, less than 40% of borderline patients who reported a remission of agoraphobia, simple phobia, OCD, or GAD, later reported a recurrence of these disorders.

Figure 2.

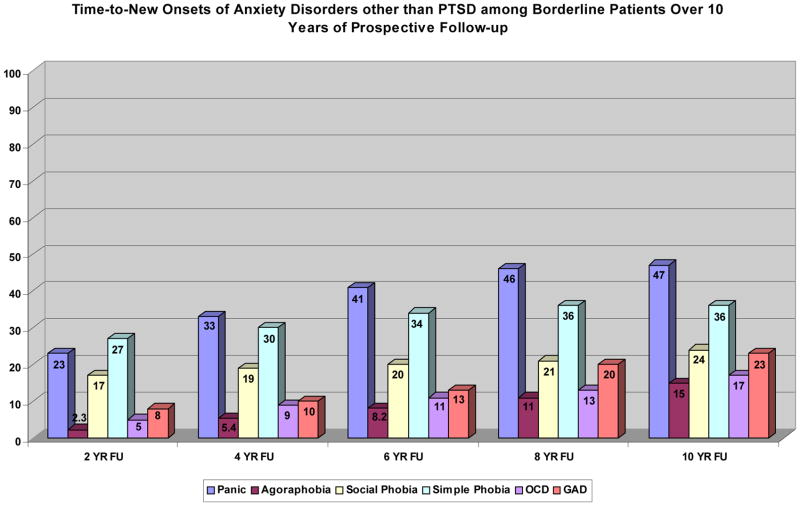

3.3. New Onsets

Figure 3 details the rates of new onsets of panic, agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, OCD, and GAD among borderline patients who had not met criteria for these disorders at baseline. The rates of new onsets of the studied anxiety disorders among borderline patients who had not reported meeting criteria for them at baseline are as follows: 15% for agoraphobia, 17% for OCD, 23% for GAD, 24% for social phobia, 36% for simple phobia, and over 45% for panic disorder.

3.4. Axis II Comparison Subjects

As for axis II comparison subjects, we found remission rates of 100% for all anxiety disorders studied. In addition, the following cumulative percentages were found for recurrence of the studied anxiety disorders: simple phobia (21%), social phobia (36%), panic (56%), agoraphobia (100%), and OCD (100%). No axis II comparison subjects reported meeting criteria for GAD at baseline. Finally, the following cumulative percentages were found for new onsets of the studied anxiety disorders: agoraphobia (5%), OCD (6%), GAD (6%), social phobia (8%), simple phobia (22%), and panic (34%). However, these rates of remission, recurrence, and new onsets need to be interpreted with caution due to the small number of subjects in each risk set.

In terms of between-group differences, rates of recurrence were about the same for both groups of subjects for all disorders (panic disorder: HR=0.71, 95%CI=0.28, 1.80; social phobia: 1.06, 95%CI=0.34, 3.31; simple phobia: HR=1.37, 95%CI=0.30, 6.38). For agoraphobia, OCD, and GAD, the number of subjects was too small for statistical comparisons. However, borderline patients had a significantly lower rate of remission from panic disorder than axis II comparison subjects (HR=0.16, 95%CI=0.03, 0.81). In contrast, borderline patients had significantly higher rates of new onsets of panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, and GAD (panic disorder: HR=2.25, 95%CI=1.27, 3.98; agoraphobia: HR=4.28, 95%CI=1.02, 17.9; social phobia: HR=3.44, 95%CI=1.19, 9.96; GAD: HR=2.46, 95%CI=1.27, 3.98).

4. Discussion

Four important findings have emerged from this study. The first of these findings is that the prevalence of these disorders, which in aggregate were three times as common at baseline as the rate found in the general US population (Kessler et al., 1994), declined significantly over time for those with BPD (and also for axis II comparison subjects). These findings are consistent with and extend the findings of our six-year follow-up study of this sample (Zanarini et al., 2004).

The second of these findings is that remissions were very common among both of our study groups. For those with BPD, remission rates ranged from a low of 77% (OCD) to a high of 100% (agoraphobia and GAD). In a like manner, all comparison subjects with one of these anxiety disorders at baseline experienced a remission at a later time period. Our results for borderline patients followed for a decade are consistent with the findings of the HARP study for panic disorder, particularly for women, after eight years of follow-up (Yonkers et al., 2003). However, our rates of remission for social phobia, GAD, and OCD are substantially higher than those found in the HARP study at eight and at 15-year follow-up. The reasons for these differences are not clear but may be due to the fact that the HARP study was following participants with primary anxiety disorders (Yonkers et al., 2003; Marcks et al., 2011), while MSAD participants primarily suffered from secondary anxiety disorders. Additionally, these differences are particularly notable as the HARP study required an eight-week period of remission (Massion et al., 2002), while MSAD required a two-year period.

The third of these findings is that recurrences of these disorders were also quite common. More specifically, about a third of borderline patients with a remission of agoraphobia, simple phobia, and GAD experienced a recurrence. In a like manner, about 40% of borderline patients with a remission of social phobia and OCD experienced a recurrence. In contrast, a recurrence of panic disorder was experienced by 65% of borderline patients with a prior remission of this disorder. These rates of recurrence are consistent with those found in the HARP study at eight-15-year follow-up (Marcks et al., 2011).

The fourth major finding is that rates of new onsets of these disorders varied considerably. By ten years of follow-up, less than 20% of borderline patients experienced new onsets of agoraphobia and OCD and less than 25% of borderline patients experienced new onsets of social phobia and GAD. In contrast, 36% of borderline patients had experienced a new onset of simple phobia and 47% had experienced a new onset of panic disorder.

These findings have several clinical implications. The first is that anxiety is an intermittent and serious problem for many borderline patients. This finding, in turn, suggests that clinicians might want to assess for the severity of anxiety symptoms in general and the presence of co-occurring anxiety disorders specifically. This finding also suggests that clinicians might expect fluctuations in the severity of symptoms of anxiety over time.

The second of these implications is the need for effective treatments for these anxiety symptoms and disorders in borderline patients. Currently there are six empirically validated, manual-based forms of psychotherapy for BPD: dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) (Linehan et al. 1991); mentalization-based treatment (MBT) (Bateman & Fonagy, 1999); schema-focused therapy (SFT) (Giesen-Bloo et al. 2006); transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) (Clarkin et al. 2007); Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) (Blum et al. 2008); and General Psychiatric Management (GPM) (McMain et al. 2009). However, none of these treatments, two of which have been assessed in multiple studies (DBT and MBT), primarily focuses on anxiety as a symptom of BPD. Therefore, new treatments that primarily focus on these symptoms and disorders in those with BPD would be useful. Anxiolytics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics are all commonly used to treat the anxiety of borderline patients. However, there is no evidence that they are particularly effective for treating these troubling symptoms.

This study has two main limitations. The first is that all of the patients were seriously ill inpatients at the start of the study. A second limitation is that about 90% of those in both patient groups were in individual therapy and taking psychotropic medications at baseline and about 70% were participating in each of these outpatient modalities during each follow-up period (Hörz et al. 2010). Thus, it is difficult to know if these results would generalize to a less disturbed group of patients or people meeting criteria for BPD who are not in treatment.

It is also important to note that the 2-year time period to assess a remission differs from the DSM-III-R conception of a remission for anxiety disorders. The longer time period, though, serves to strengthen the robustness of our finding on remissions and gives it more clinical relevance.

Our findings suggest that anxiety is a core feature of BPD. Current research has shown that anxiety sensitivity (i.e., anxiety sensitivity refers to a person’s tendency to fear anxiety-related symptoms due to the belief that there will be some negative physical, social, or emotional outcome as a result of having those symptoms) serves as a vulnerability factor for both anxiety disorders and BPD, providing evidence that the two might be fundamentally related (Gratz et al., 2008). More specifically, this research has found that experiential avoidance (i.e., an unwillingness to endure upsetting emotions, thoughts, and memories) may serve as the mediating factor between anxiety sensitivity and BPD. Further research into the mediating factors of anxiety disorders and BPD might be useful in determining key targets for therapy.

5. Conclusions/Implications

The results of this study suggest that anxiety disorders are intermittent conditions for those with BPD as remissions and recurrences are common. These results also suggest that anxiety disorders are almost ubiquitous as new onsets add to already high baseline prevalence rates.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH grants MH47588 and MH62169.

References

- Ansell EB, Pinto A, Edelen MO, Markowitz JC, Sanislow CA, Yen S, Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM. The association of personality disorders with the prospective 7-year course of anxiety disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;14:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum N, St John D, Pfohl B, Stuart S, McCormick B, Allen J, Arndt S, Black DW. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:468–478. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality: a multiwave study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:922–928. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, van Tilburg W, Dirksen C, van Asselt T, Kremers I, Nadort M, Arntz A. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:649–658. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Gunderson JG. Preliminary data on the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and borderline personality disorder: The role of experiential avoidance. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hörz S, Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. Ten-year use of mental health services by patients with borderline personality disorder and with other axis II disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:612–616. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.6.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Personality disorders evident by early adulthood and risk for anxiety disorders during middle adulthood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:408–426. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcks BA, Weisberg RB, Dyck IR, Keller MB. Longitudinal course of obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with anxiety disorders: a 15-year prospective follow-up study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;22 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.01.001. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion AO, Dyck IR, Shea T, Phillips KA, Warshaw MG, Keller MB. Personality disorders and time to remission in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:434–440. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, Guimond T, Cardish RJ, Korman L, Streiner DL. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1365–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rational, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Bruce SE, Dyck IR, Keller MB. Chronicity, relapse, and illness—course of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder: Findings in men and women from 8 years of follow-up. Depression and Anxiety. 2003;17:173–179. doi: 10.1002/da.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG. The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: Interrater and test-retest reliability. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo E, Sickel MA, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1733–1739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. Mental health service utilization of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:28–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Axis I comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder: 6-year follow-up and prediction of time to remission. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2108–2114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. Time to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder and stability of recovery: A 10-year prospective follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:663–667. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. The interrater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The revised diagnostic interview for borderlines: Discriminating BPD from other axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Hörz S, Frankenburg FR, Weingeroff J, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. The 10-year course of PTSD in borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011 May; doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01717.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]