Abstract

Personality traits are known to be associated with a host of important life outcomes, including interpersonal dysfunction. The interpersonal circumplex offers a comprehensive system for articulating the kinds of interpersonal problems associated with personality traits. In the current study, traits as measured by the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) in a sample of 124 young women were correlated with interpersonal dysfunction as measured by the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex. Results suggest that MPQ traits vary in their associations with interpersonal distress and in their coverage of specific kinds of interpersonal difficulties among women undergoing the transition to adulthood.

It is well-known that personality traits promote or inhibit adaptive outcomes in general and relational success in particular (Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006). Less is known about the specific associations of certain personality traits with particular kinds of interpersonal dysfunction. It is also unclear how the link between traits and interpersonal functioning might be affected by demographic variables such as age and gender. Developmental research implicates the transition to adulthood (Arnett, 2000) as a particularly salient period in that it is associated both with the consolidation of traits and socialization processes (Hopwood et al., 2010). Socialization processes during this time might be particularly prescient for young women (Mezulis et al., 2010). Given that little is known about the specific associations between personality traits and interpersonal dysfunction among women during the transition to adulthood, the purpose of this study is to examine the links between normative personality and interpersonal problems in a sample of young women.

Measuring Personality Traits

Personality research suggests that various personality trait models can be integrated in a consensual hierarchical model (Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005; Watson, Clark, & Harkness, 1994) and that widely used normal personality measures tend to predict similar levels of variance in substantial life outcomes (Grucza & Goldberg, 2007). These findings suggest that most contemporary broadband personality inventories measure similar variance in personality, even if they organize that variance differently, for instance by having varying numbers of higher order traits. One particularly important level involves the three traits that are thought to reflect underlying temperamental dispositions for variability in affective experiences, often referred to as positive emotionality (PEM), negative emotionality (NEM), and constraint (CON). The Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen & Waller, 1994) is a widely used and well-validated measure that is structured by these higher order traits. Lower order MPQ scales depict individual differences related to each of these higher order traits. PEM has four lower order scales called well-being, social potency, achievement, and social closeness, NEM has three traits called stress reaction, alienation, and aggression, and CON has three traits labeled control, harm avoidance, and traditionalism. There is also an absorption scale that does not fit neatly under any of the ‘big three’ factors, and which indicates responsiveness to evocative sensory stimuli and the tendency to become engrossed. It is particularly interesting to examine the relations between the MPQ and interpersonal functioning given that the explicit focus of the MPQ is on affect, yet predictions can be made about how various affective dispositions might lead to certain interpersonal styles or problems (Tellegen & Waller, 1994, p. 270).

Measuring Interpersonal Problems

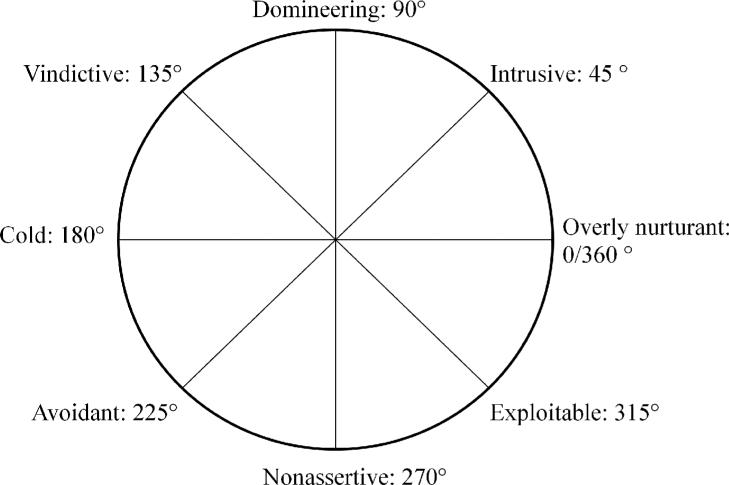

The interpersonal circumplex (IPC) offers a nomological net (Gurtman, 1992) with which to conceptualize the relations between criterion measures and interpersonal variables. The IPC assesses interpersonal functioning in the form of a circle structured by two orthogonal dimensions, agency (dominance to submissiveness) and communion (warmth to coldness). This broad yet efficient sampling of interpersonal behaviors permits researchers to ‘map’ personality traits onto the IPC so that more precise inferences can be made about the interpersonal consequences of particular dispositions. Available IPC measures provide indications of different kinds of interpersonal functioning, including traits, values, efficacies, and sensitivities. The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex (IIP-C; Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 1990) is particularly useful when research questions involve adaptivity, as it assesses difficulties and distress associated with interpersonal functioning. Figure 1 displays the octant labels of the IIP-C.

Figure 1.

The Interpersonal Problems Circumplex.

Because the IIP-C is a circumplex instrument its scales have a specific structure and expected pattern of inter-correlations. One consequence of this pattern is that it would be inefficient and psychometrically inappropriate to examine bivariate correlations between MPQ traits and each IIP-C scale in isolation. It is more informative to interpret the relations between MPQ traits and the IIP-C using interpersonal structural summary parameters that account for the circumplexity of the IIP-C (Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998). Structural summary parameters indicate the shape of the waveform that is created when the correlations between a criterion measure and IIP-C octant scores are plotted such that the octants are arrayed across the X-axis and the magnitude of correlations are indicated on the Y-Axis. In a circumplex, these correlations would be expected to take the shape of a sine wave.

There are three such parameters. Elevation is the average correlation between a given trait and non-specific problems, and is typically interpreted as an indicator of interpersonal distress, since a variable with a strong average correlation would indicate more interpersonal problems across the octants. Amplitude is the difference between the peak of a wave form and elevation, and is a measure of discriminability among criterion correlations, or alternatively the degree of structured patterning of criterion correlations across the octants. High amplitudes suggest a differentiated pattern, with some strong and some weak correlations, whereas low amplitudes would suggest that the correlations tended to be similar across the octants. Displacement indicates the area of the IIP-C onto which the wave form peaks, assuming the pattern of correlations is wavelike, as predicted. It suggests the interpersonal theme of the criterion variable, and is expressed in degrees where overly-nurturant (warmth) is 0°, domineering (dominance) is 90°, coldness is 180°, and nonassertiveness (submissiveness) is 270° (see Figure 1). Finally, an R2 coefficient can be computed to indicate the overall goodness of fit of the observed pattern of correlations between traits and IIP-C scales to a perfect sine wave, as would be expected for a circumplex measure. High R2 values suggest that the three parameter model is valid and interpretable, whereas lower R2 values (e.g., < .70) render the three parameter summary less effective in describing the pattern of correlations.

Associations between Personality Traits and Interpersonal Problems

A number of normative personality traits have been mapped onto IPC instruments that measure normative interpersonal styles (e.g., Wiggins & Broughton, 1991). For instance, among five-factor model personality traits, the agentic dimension of the IPC represents a slightly rotated variant of extraversion, whereas the communal dimension is a slightly rotated version of agreeableness. Specifically, extraversion is slightly more communal than dominance and agreeableness is slightly more submissive than warmth (McCrae & Costa, 1989; Trapnell & Wiggins, 1990; note that some research also suggests that other five-factor traits systematically relate to the IPC as well, c.f. Ansell & Pincus, 2004).

Researchers interested in mapping personality traits onto the interpersonal problems circumplex have tended to focus on traits with a clinical valence, such as personality disorders (Wiggins & Pincus, 1989) or empathy (Gurtman, 1992). Several reliable associations have been observed between personality disorder constructs and the IIP-C, such as the consistent finding that histrionic traits are associated with intrusiveness problems (Monsen et al., 2006; Pincus & Wiggins, 1989). Pathological trait models also evince predictable correlations with the IIP-C (Hopwood, Koonce, & Morey, 2009). For example, Simonsen and Simonsen (2009) showed that, among the higher order scales of the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology (DAPP), emotional dysregulation was associated with interpersonal distress, dissocial behavior was associated with domineering tendencies, inhibitedness with interpersonal avoidance, and compulsivity did not show strong interpersonal problem correlates.

In one of the few studies to evaluate the relations between a normal personality measure and the IIP-C, Nysaeter et al. (2009) found in a non-clinical sample of adults that NEO-FFI neuroticism was associated with interpersonal distress, extraversion and openness were negatively associated with avoidance, agreeableness was negatively associated with vindictiveness, and conscientious had limited specific relations with the IIP-C. Overall, these results suggest that trait dispositions are informative for understanding specific kinds of interpersonal difficulties. However, no study has tested such relations among young women specifically, used other popular trait measures such as the MPQ, or investigated the relations between lower order personality facets and interpersonal problems.

Purpose of the Present Study

The potential for valid inferences regarding implications of MPQ trait scores and profiles for indicating the extent and nature of interpersonal distress in general and among young women in particular is constrained by this lack of research. This study was designed to address these limitations by relating MPQ higher and lower order traits onto the IIP-C in a sample of women during the transition to adulthood.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 124 young women drawn from the community via the Michigan State University Twin Study (MSUTR). The MSUTR is a population-based twin registry examining genetic, environmental, and neurobiological risk factors for psychopathology across development among monozygotic and dizygotic twins (for more information on the MSUTR, including subject recruitment, see Klump & Burt, 2006). The MSUTR includes several different twin projects, but participants in the current study were sampled from the Twin Study of Hormones and Behavior across the Menstrual Cycle, a project whose primary goals focused on understanding hormonal mechanisms of eating pathology during the transition to adulthood. The average age of study participants was 18.02 years (range = 16 – 22 years; S.D. = 1.79) and 81% of participants were Caucasian.

Measures

Participants completed the MPQ-brief form (Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002). This 155-item measure has a true-false response format and scales measuring the three higher order traits in Tellegen's affective temperament model of personality (Positive Emotionality, Negative Emotionality, and Constraint), their lower-order traits as described above, and Absorption, which tends to split off as somewhat independent of the other scales in factor analyses of the MPQ (e.g., Tellegen & Waller, 1994). All MPQ scales had internal consistency coefficients > .70.

Participants also completed the 64-item IIP-C (Alden et al., 1990). IIP-C items have a 5-point response format. The 64 items are arrayed evenly across the eight octant scales: overly nurturant (i.e., warm, 0/360°), intrusive (warm-dominant, 45°), domineering (dominant, 90°), vindictive (cold-dominant, 135°), cold (DE, cold, 180°), avoidant (cold-submissive, 225°), nonassertive (submissive, 270°), and exploitable (warm-submissive, 315°). All IIP-C scales had internal consistency coefficients > .70.

Analyses

Correlations between the IIP-C octant scales and criterion measures, in this case MPQ trait scales, are the basis for computing structural summary parameters. However, because we sampled twins there are dependencies in the data such that relationships among subjects (i.e., twins) could affect these correlations. Correlations between MPQ traits and IIP-C octant scales were therefore estimated in AMOS 19.0 using a path modeling approach designed to address potential issues with data dependency. In each model the MPQ trait for each twin and the IIP-C octant scale represented measured variables. Zygosity was not modeled. Variable means and variances were constrained to be equal across twins. Cross-trait, cross-twin covariances (e.g., from twin 1's MPQ trait to twin 2's IIP-C octant scale) were also constrained to be equal. Cross-twin within-trait covariances (e.g., between twin 1 and twin 2 MPQ trait score) were estimated freely. Most relevant to this study, correlations (the standardized covariance of MPQ trait with IIP-C octant scale) were constrained to be equal as well; this coefficient served as the estimate of association between MPQ trait and IIP-C octant for each model. These estimates were then used to compute the structural summary parameters for each trait as described above.

Results

Table 1 shows the IIP-C structural summary parameters for the higher and lower order MPQ traits. Elevation values depict whether each trait is positively or negatively associated with interpersonal distress. NEM (.30) and stress reaction (.34) were unique in that they had elevation values > .20, suggesting that higher levels of these traits are associated with more interpersonal distress. No trait had an elevation value < -.20. For the purposes of this study, we regarded a goodness of fit value > .70 as sufficient for meaningfully interpreting displacement values. NEM, PEM, and seven lower order traits met this criterion. Given reasonable specificity in terms of relations with IIP-C octants and consistency of the pattern of correlations to circumplex expectations, inferences can be made based on displacement and amplitude values about the nature of interpersonal problems connoted by these traits. In general, NEM projects towards vindictiveness on the IIP-C, as do lower order scales stress reaction, alienation, and aggression. PEM, well-being, and social closeness project in the direction of nurturance. Achievement projects to exploitability and social potency projects towards the domineering octant.

Table 1.

IIP-SC Structural Summary Parameters for MPQ higher order and lower order scales.

| Elevation | Amplitude | Displacement | Octant | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emotionality | -0.08 | 0.23 | 20.86° | warm | 0.89 |

| Negative Emotionality | 0.30 | 0.22 | 125.03° | cold dominant | 0.93 |

| Constraint | -0.14 | 0.03 | (255.32°) | 0.05 | |

| Well Being | -0.05 | 0.20 | 359.17° | warm | 0.89 |

| Social Potency | -0.02 | 0.24 | 93.37° | dominant | 0.95 |

| Achievement | -0.06 | 0.15 | 335.81° | warm submissive | 0.76 |

| Social Closeness | -0.11 | 0.28 | 4.86° | warm | 0.93 |

| Stress Reaction | 0.34 | 0.13 | 129.89° | cold dominant | 0.85 |

| Alienation | 0.15 | 0.14 | 133.24° | cold dominant | 0.89 |

| Aggression | 0.17 | 0.24 | 125.50° | cold dominant | 0.88 |

| Control | -0.08 | 0.11 | (288.58°) | 0.52 | |

| Harm Avoidance | -0.14 | 0.05 | (162.20°) | 0.29 | |

| Traditionalism | -0.09 | 0.02 | (128.65°) | 0.04 | |

| Absorption | 0.19 | 0.02 | (221.51°) | 0.14 | |

Note. Parentheses indicate that, based on low R2 values, the interpretation of displacement is questionable. Octant descriptions are not given for parenthesized displacement values.

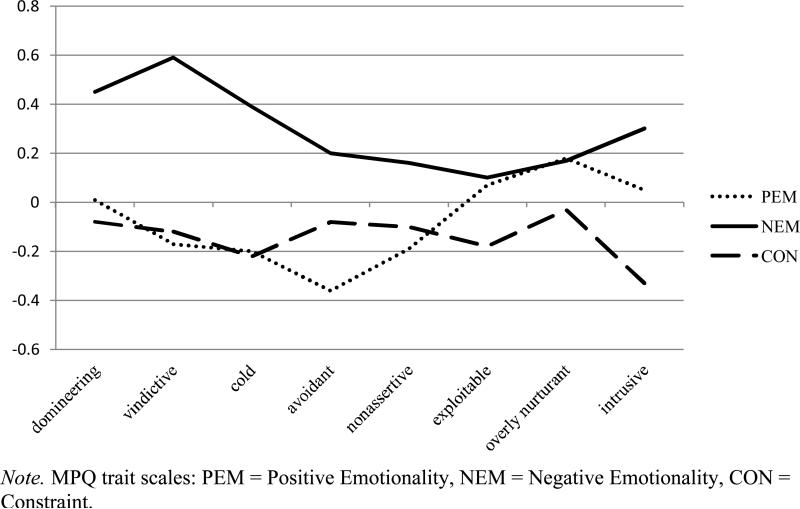

Plots of the actual correlations permit a more specific analysis of the relations of MPQ traits with IIP-C octants. These plots are given in Figures 2-5. Figure 2 depicts higher order MPQ traits. The higher elevation for NEM is seen in its curve being above those of PEM or CON on all octants except overly nurturant. It can also be observed that the curve for CON is flatter overall, which is indicated by its relatively lower amplitude value. Finally, the various displacement parameters are indicated by the peaks in the curves for each trait – NEM's peak is around vindictiveness, PEM's peak is around overly nurturant, as is CON's (but this peak is not interpretable because of the very low R2 value).

Figure 2.

Correlations of MPQ higher order traits with IIP-C octant scales.

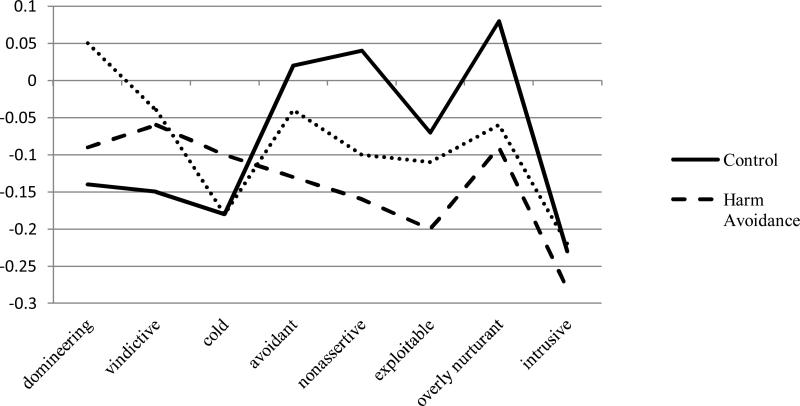

Figure 5.

Correlations of MPQ lower order Constraint traits with IIP-C octant scales.

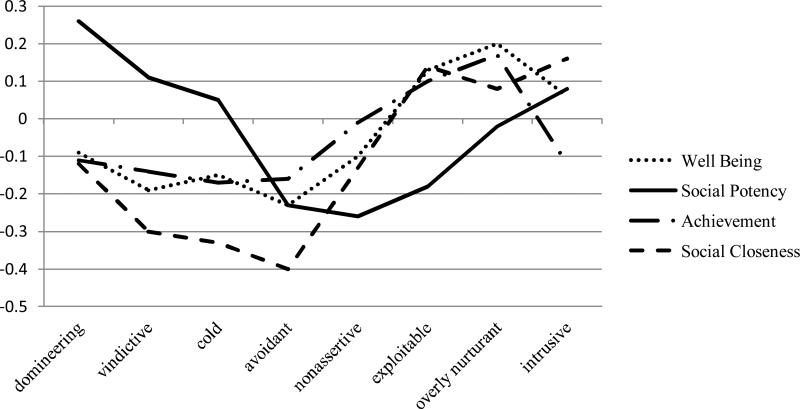

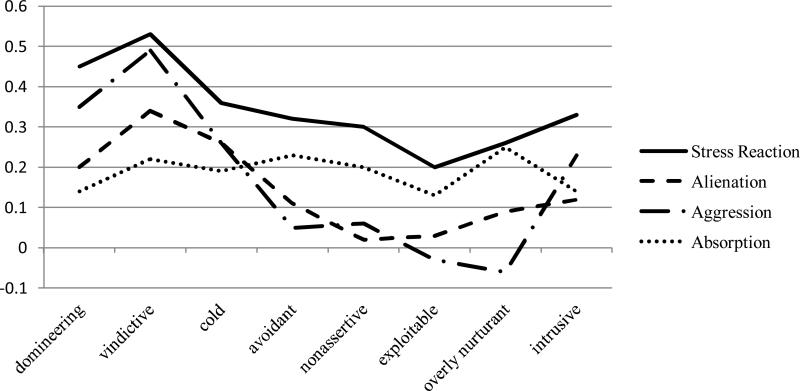

Figure 3 depicts correlations between lower order PEM traits and IIP-C octants. All of these traits had interpretable curves and appreciable amplitudes. They also had similar elevations, indicating that positive emotionality is negatively related to interpersonal distress. These traits were distinguished by their displacement values. In particular, the peak for social potency was in the direction of domineering whereas the peaks for the other three traits were near exploitable or overly nurturant. Figure 4 depicts correlations between lower order NEM traits and absorption with the IIP-C octants. The NEM traits all had more distinct waves than absorption, which had low amplitude and R2 values. Each of the NEM traits had similar displacements, with all waves peaking near vindictiveness, although the wave for aggression was the most distinct, as also indicated by its relatively higher amplitude value.

Figure 3.

Correlations of MPQ lower order Positive Emotionality traits with IIP-C octant scales.

Figure 4.

Correlations of MPQ lower order Negative Emotionality traits and Absorption with IIP-C octant scales.

Finally, Figure 5 depicts the correlations between MPQ Constraint traits and the IIP-C octants. All of these patterns need to be interpreted with the negative elevation parameters, which indicate that in general higher constraint is associated with lower interpersonal distress, in mind. Furthermore, each of these traits had low R2 values, but this was not because of flat profiles. Instead, each trait shows a somewhat complicated and idiosyncratic pattern of correlations with the IIP-C scales. Control has peaks at both overly nurturant and nonassertive, indicating people with greater control over their impulses (i.e., self-control rather than interpersonal control) tend to be warm and submissive (but not necessarily warm-submissive, or JK). The strongest absolute correlate with control was the cold octant, indicating young women with higher control are least likely to be cold. Harm avoidance has negative peaks at both intrusive and exploitable, but a relatively small negative correlation with overly nurturant, indicating that while young women who avoid sensation-seeking would be unlikely to be either intrusive or dependent, this tendency is not necessarily related to warmth. Traditionalism has a positive peak at domineering, but strong negative peaks at intrusive and cold, suggesting that more traditional young women may tend to have some problems being domineering, but they are quite unlikely to be intrusive or cold.

Discussion

No previous study has mapped normal traits as assessed by the MPQ onto interpersonal problems as assessed by the IIP-C in a sample of women during the transition to adulthood. Results are informative for depicting the kinds of interpersonal dysfunction that can be expected among young women based on trait dispositions. In general, women with more negative emotions (NEM) experience more interpersonal distress. Although there were modest relations suggesting higher PEM and CON are associated with fewer interpersonal problems, these effects were weaker than that of NEM. Stress reaction, in particular, was associated with a greater propensity for interpersonal distress.

A handful of MPQ traits showed specific relations to interpersonal problems. PEM traits generally indicated the potential for individuals to be domineering, intrusive, or overly nurturant. Three traits peaked in the direction of nurturance, indicating that greater positive emotionality and well-being in general and need for social closeness in particular indicate a warm interpersonal style. Although this might suggest that, when they have problems, people high on these traits may tend to sacrifice their personal needs for the benefit of others, we note that these traits also have negative elevations, suggesting that they are associated with a lack of interpersonal distress and dysfunction in general. Achievement-striving peaked at exploitability, which is surprising as we might have predicted this trait to associate with interpersonal dominance. One possibility is that this effect related to our sampling women and that gendered expectations for success in women require more subversion of personal relative to others’ needs. This hypothesis should be tested in mixed-sex adolescent samples. Social potency projected towards domineering, which is consistent with Tellegen and Waller's (1994) suggestion that elements of PEM capture both communal (i.e., social closeness, well-being) and agentic (i.e., social potency) strivings and associated problems.

NEM and associated traits stress reaction, aggression, and alienation were correlated with problems involving vindictiveness. Overall, both the specificity and the lack of differentiation in this pattern is somewhat surprising, as we had expected NEM to show a strong elevation but non-specific displacement, and one might expect the interpersonal themes of the three NEM facets to vary. For example, although more aggressive manifestations of negative emotionality might be expected to associate with vindictiveness, one might also predict that more internalizing NEM dimensions such as stress reaction and alienation should be more linked to coldness or avoidance.

No traits were specifically associated with problems involving intrusiveness, nonassertiveness, avoidance, or coldness This suggests that, while MPQ traits do permit valid predictions about interpersonal dysfunction among women during the transition to adulthood involving being too dependent, self-sacrificing, domineering, and vindictive, they are not sufficient for fully understanding the variations of interpersonal problems women might experience. Furthermore, while traits related to PEM, and social closeness in particular, had displacement values in the direction of nurturance, none of these had positive elevations, meaning that they do not measure warm problems per se. Although there was a slight positive correlation between control and the overly nurturant scale, overall results suggest that, as with other trait measures (Hopwood et al., 2009), the MPQ may be limited in its assessment of warm problems.

From an applied perspective, limitations in the MPQ for indicating certain types of interpersonal problems indicates that interpersonal trait measures (e.g., Markey & Markey, 2010; Wiggins, 1979) would provide incremental information over the MPQ in indicating the kinds of interpersonal dysfunction experienced by women during the transition to adulthood. This is particularly so because interpersonal trait measures tend to have positive correlations with their corresponding octant scores on the IIP-C (Alden et al., 1990). However, it is also possible that these results relate to the composition of the sample; thus the generalization to men and participants of different ages is an important issue for further research.

Another important direction for ongoing research involves the longitudinal associations between traits and interpersonal problems, particularly among young women during the transition to adulthood. One might expect that traits, which are thought to be rooted primarily in affective temperament characteristics that are strongly heritable (Tellegen & Waller, 1994), may be mostly dispositional, and thus interpersonal problems may be consequences of or characteristics adaptations to these trait dispositions. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study prohibits inferences regarding the directionality of relations between traits and interpersonal problems. It will be important for developmental research to test this hypothesis. Similarly, it might be expected that MPQ traits would be more strongly heritable than IIP-C dimensions, given the strong theoretical role of the environment in interpersonal functioning (e.g., Critchfield & Benjamin, 2010). Behavior genetic research in larger samples would be useful for testing this hypothesis. Non-twin research would also be informative, as although subsidiary analyses suggested that results were quite similar across samples of randomly selected twins, it is an open question how well these results would generalize to non-twins.

One strength of this study is that it focused on a demographic group, young women, for whom trait-interpersonal problem relations might be particularly important, as traits tend to coalesce during young adulthood (Hopwood et al., 2010) and interpersonal problems may be particularly salient for young women (Mezulis et al., 2010). However, while it is useful to focus on a specific demographic group to highlight issues most relevant to that group, research on the relations between normal traits, particularly as measured with the MPQ, and interpersonal problems is generally limited and future research should continue to study these relations in other demographic groups and with other personality measures. This would permit more general inferences about how these instruments relate to one another as well as the comparison of effects across young women and other groups. Finally, research using other assessment methods such as informant reports would be useful to address any limitations associated with mono-method research in general or self-report questionnaires in particular.

These limitations aside, the current study provided new information about the associations of personality dispositions with interpersonal problems among women during a developmentally important period, and the results have significant implications for personality, social, developmental, assessment, and clinical psychology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brent Donnellan for his consultation on this project. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH0820-54) awarded to Drs. Klump, Boker, Burt, Keel, Neale, and Dr. Cheryl Sisk. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Christopher J. Hopwood, Michigan State University

S. Alexandra Burt, Michigan State University.

Pamela K. Keel, Florida State University

Michael C. Neale, Virginia Commonwealth University

Steven M. Boker, University of Virginia

Kelly L. Klump, Michigan State University

References

- Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL. Construction of circumplex scales for the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;55:521–536. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Pincus AL. Interpersonal perceptions of the five-factor model of personality: An examination using the structural summary method for circumplex data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:167–201. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield KL, Benjamin LS. Assessment of repeated relational patterns for individual cases using the SASB-based Intrex questionnaire. Journal of Assessment of Personality. 2010;92:480–489. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.513286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Goldberg LR. The comparative validity of 11 modern personality inventories: Predictions of behavioral acts, informant reports, and clinical indicators. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89:167–187. doi: 10.1080/00223890701468568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman MB. Construct validity of interpersonal personality measures: The interpersonal circumplex as a nomological net. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman M, Balakrishnan J. Circular measurement redux: the analysis and interpretation of interpersonal circle profiles. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:344–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Donnellan MB, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt SA. Genetic and environmental influences on personality trait stability and growth during the transition to adulthood: A three wave longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:545–556. doi: 10.1037/a0022409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Koonce EA, Morey LC. An exploratory study of integrative personality pathology systems and the interpersonal circumplex. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Markey PM, Markey CN. A brief assessment of the interpersonal circumplex: The IPIP-IPC. Assessment. 2009;16:352–361. doi: 10.1177/1073191109340382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr. The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggin's circumplex and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:586–595. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezulis AH, Funasaki KS, Charbonneau AM, Hyde JS. Gender differences in the cognitive vulnerability-stress model of depression in the transition to adolescence. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34:501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Monsen JT, Hagtvet KA, Havik OE, Eilertsen DE. Circumplex structure and personality disorder correlates of the interpersonal problems model (IIP-C): Construct validity and clinical implications. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:165–173. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Yen S, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH. Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:983–994. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nysaeter TE, Langvik E, Berthelsen M, Nordvik H. Interpersonal problems and personality traits: The relation between IIP64C and NEO-FFI. Nordic Psychology. 2009;61:82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer D, Benet-Martínez V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:401–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JC, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:150–163. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Wiggins JS. Interpersonal problems and conceptions of personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;4:342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen S, Simonsen E. The Danish DAPP-BQ: Reliability, factor structure, and convergence with the SCID-II and IIP-C. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:629–646. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Waller NG. Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. In: Briggs SR, Cheek JM, editors. Personality measures: Development and evaluation. Vol. 1. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell PD, Wiggins JS. Extension of the interpersonal adjective scales to include the big five dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:781–790. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Harkness AR. Structures of personality and their relevance for psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:18–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Broughton R. A geometric taxonomy of personality scales. European Journal of Personality. 1991;5:343–365. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Pincus AL. Conceptions of personality disorders and dimensions of personality. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;1:305–316. [Google Scholar]