Abstract

Hairs are known as a sensory apparatus for touch. Their follicles are innervated predominantly by palisade endings composed of longitudinal and circumferential lanceolate endings. However, little is known as to how their original primary neurons make up a part of the ending. In this study, innervation of the palisade endings was investigated in the auricular skin of thy1-YFP transgenic mouse. Major observations were 1) Only a small portion of PGP9.5-immunopositive axons showed YFP-positivity, 2) All of thy1-YFP-positive sensory axons were thick and myelinated, 3) Individual thy1-YFP-positive trunk axons innervated 4–54 hair follicles, 4) Most palisade endings had a gap of lanceolate ending arrangement, 5) PGP9.5-immunopositive 10–32 longitudinal lanceolate endings were closely arranged. Only a part of them were thy1-YFP-positive axons that originated from 1–3 afferents, and 6) Single nerve bundles of the dermal nerve network included both bidirectional afferents. Palisade endings innervated by multiple sensory neurons might be highly sensitive to hair movement.

Keywords: hair follicle, lanceolate ending, touch sense, single afferent, three dimensional analysis, thy1-YFP transgenic mouse

Introduction

Hairy skin is an essential sensory apparatus in mammals.1–6) Body surface of most fur-bearing mammals is densely covered by both guard and vellus hairs. In addition, a certain number of vibrissa hairs are provided to their facial hairy skin and the wrist.7,8) Vibrissa follicles are well known as an important tactile sensory organ. Over the years, a great deal of effort has been spent in anatomical and physiological investigations on their innervation.7–14) Several types of mechanoreceptors, such as the Merkel endings, the lanceolate endings, the Ruffini-like endings and the lamellated endings, were identified in the vibrissa follicles. Dense and well arranged distribution of all endings can be observed in each follicle.14)

On the other hand, the follicles of common guard and vellus hairs are small in size compared to the vibrissa follicles, however, they are well-innervated by palisade endings.1–6) Each follicle has a palisade ending which is distributed around the outer root sheath at the level of just below the sebaceous gland.4–6,13) It is composed of a certain number of longitudinal lanceolate endings and a few circumferential lanceolate endings.2,9) The former is thought to be supplied by myelinated nerve fibers and the latter by a mixture of myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers.2) The circumferential lanceolate endings are sparsely distributed in vellus hairs.12) In these days, they call cluster of only longitudinal lanceolate endings as a palisade ending. It is known that the innervation of guard and vellus hairs is derived from afferents of the nerve plexus in deep dermis.12) And the longitudinal lanceolate endings are physiologically known as rapidly adapting (RA) receptors15,16) and the circumferential lanceolate endings as slowly adapting (SA) receptors.17) However, little is known about their precise innervation in the complicatedly distributed skin nerve plexus and about original primary sensory neurons.

The aim of this study was to clarify how single sensory afferents individually make their receptive fields. We focused our attention to the palisade endings in the murine auricular skin. The auricle is composed of two skin layers and cartilage in between them. Since the auricular skin contains thinner dermis, less hair follicle and less adipose tissue compared to any other body parts, the skin tissue is suitable for analysis of innervation. In previous studies, number of hair follicles, hair types, nerve bundle distribution and afferents innervating hair follicles were demonstrated in the rabbit auricles.18,19) Distribution of lamellated corpuscles and their afferents in the murine auricular skin were evaluated by means of acetylcholinesterase enzyme histochemistry and silver impregnation staining.20) Several studies precisely described the ultrastructures of the palisade endings and turnover of the endings.5,6,8) However, little is known about their receptive fields and the precise three-dimensional architectures of the palisade endings.

No matter how specific neuronal markers well discriminate nerve characteristics, dense nerve distribution in the skin tissue was the biggest barrier to analyze individual afferent throughout from trunk afferent to the axon terminals. Then, we found availability of thy-1 gene-expressing YFP transgenic mouse for tracing particular axons. The mouse model has been demonstrated that only a part of specific types of peripheral nerves including DRG neurons and palisade endings were clearly labelled.21–24) It was useful to trace those individual labelled axons.

We hope that these morphological observations will contribute to understand physiological response profiles of the hairy skin as a tactile sensory organ.

Materials and methods

Six normal mice (C57BL6, 4–7 weeks old, both sexes) and two thy-1 gene targeted YFP transgenic mice (Background; C57BL6, 4 and 7 weeks old respectively, female, fixed specimens were kindly provided by Prof. Raya Eilam (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel)) were used.24) All procedures used in the present studies were approved by the Meiji University of Integrative Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee (No. 22–26).

Under deep anaesthesia (sodium pentobarbital, 40 mg/kg, i.p.), animals were transcardially perfused by fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) at room temperature (RT), 30–40 ml) following 10 ml 0.1 M PB perfusion at RT. After fixation, auricles were removed and both sides of the auricular skin were slipped off from the cartilage with tweezers under a stereomicroscope. Excessive adipose tissues were removed and still thick and winding parts or most of densely hairy parts at the base of the auricles were removed. The flat and thin skin tissues were dealt as pieces of whole-mount tissues with 150–200 µm-thick (Fig. 1). They were processed after incubation in 0.1 M PB containing 0.3% triton-X100 (T-PBS) at 4 ℃ for 1–2 weeks. A long immersion in T-PBS, if necessary with under reduced pressure (reduced-pressure incubator, Taitec), was necessary at several steps of the following procedures to get good staining results.

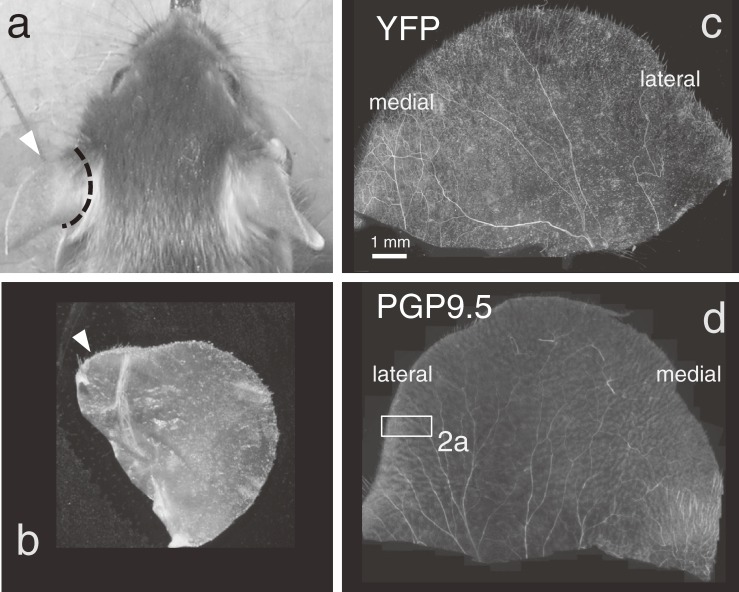

Figure 1.

Whole-mount tissue of the mouse auricular skin. a; Both left and right auricles were cut off at the dashed line and processed. Marginal edge of auricle indicates a prominent angle at the medial part (arrowhead, also seen in b). b; A piece of whole-mount tissue of the auricle. c; PGP9.5-immunopositive innervation. Rectangular; See higher magnification indicated in Fig. 2a. d; thy1-YFP-positive innervation.

Immunohistochemistry.

After one-day-long immersion in normal goat serum (1:10 in T-PBS) at 4 ℃, the tissues were stained for 1–2 weeks at 4 ℃ with appropriate combinations of primary antibodies as mixture, anti-PGP9.5 as a pan-neuronal marker, anti-NF200 for Aβ-thick axons and anti-MBP for myelin sheath. The sections were placed on a shaker once a day for 1–2 hours at RT during the incubation period. After washing off excessive primary antibodies by rinsing in T-PBS, the sections were incubated within appropriate combinations of fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies. All primary and secondary antibodies were commercial products derived from rabbit, rat or goat (see Table 1). After rinsing in 70% glycerol in T-PBS for several hours at RT following washing out of excessive secondary antibodies, the sections were mounted between two coverslips using a hydrophilic mounting medium containing DAPI for nuclear staining (Vectashieled H-1200, Vector).

Table 1.

| primary antibody | dilution | company |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-PGP 9.5 | 1:10,000 | UltraClone |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-NF 200 | 1:6,000 | Chemicon |

| Rat monoclonal anti-MBP | 1:300 | Chemicon |

| secondary antibody | dilution | company |

| Alexa488/568/633 conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit IgG | 1:500 | Invitrogen |

| Alexa488/555/633 conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG | 1:500 | Invitrogen |

Observation.

The skin tissues were observed from two sides using a spacer on stage of microscopes.25) High resolution photomicrographs were taken by means of a software (NIS-Element D, Nikon). One of its modules, Extended Depth of Focus (EDF) option, was available to allow images from different Z-axes captured by a digital camera (DXM1200, Nikon) equipped on a standard fluorescent microscope (Nikon E-800, objective lens; CFI Plan Apo 4X, 10X, VC 20X, 40X, VC 60X oil, 100X oil, numerical aperture respectively; 0.2, 0.45, 0.75, 0.95, 1.4, 1.4) to be combined into a single all-in-focus image. Photomontages to take overview of whole auricular tissues were synthesized from those focused images.

Three-dimensional analysis.

For image capture and 3D-analyses, the detailed procedure was described previously (Ebara et al., 2002, 200814,25)). Briefly, for three-dimensional analysis, confocal stack images of appropriate sites on the skin tissues were captured by confocal laser microscope systems (BioRad LaserSharp-2000 equipped on a Nikon E-800, and Nikon C1 equipped on a Nikon Eclipse 90i, objective lens were the same as the above, z-step between adjacent optical images; 1.0–0.2 µm). All images were reconstructed by using a volume rendering software (VGStudio Max 2.0, VolumeGraphics, Heiderberg, Germany). Three-dimensional volume images were consistently made along the focused axon to avoid scrambling. And the axons were traced using photo montages of the images. Several reconstructed structure were observed from every possible angle by using the reconstruction software. Removals of distractions around focused labelled axons were often made in order to discriminate continuities of the ramifications. Commonly-used photo-retouched and presentation softwares (Adobe PhotoShop CS and Microsoft PowerPoint 2007) were appropriately used to add pseudo-colours or to make photo montages.

Arbitrarily-selected 8 large palisade endings labelled by anti-PGP9.5 in the normal mouse auricular skin were three-dimensionally analyzed and the number of all lanceolate endings that constituted each palisade ending were counted. In the biggest one of those, every axon terminal of all longitudinal lanceolate endings was traced to the deep dermal nerve plexus. All ten thy1-YFP-positive afferents (trunk axons), that were recognized in a thick nerve bundle at the basal middle part of the cut edge of a posterior auricular skin, were three-dimensionally traced throughout to the nerve endings. The terminal structure of the endings, the number of innervated hair follicles, the distributional area of trunk axons and their branching pattern, derived from specified single trunk afferent, were analyzed and mapped on the focused photomontage of the auricular skin.

Results

Innervation in the auricular skin was well observed in our whole-mount preparations with two-side observations (Fig. 1).

Murine auricular hairy skin.

Hairs distributed in both sides of auricular skin were mostly thick vellus hairs that mostly had short hair shaft in outside of the skin surface in addition to scattered guard hairs. Vellus hairs were individually distributed evenly across each other without showing any compact cluster of hair follicles and any eccentric distribution density of follicles throughout the auricular surface (Fig. 2a). No differences were recognized between inferior and posterior skin of the auricles in the hair distribution patterns.

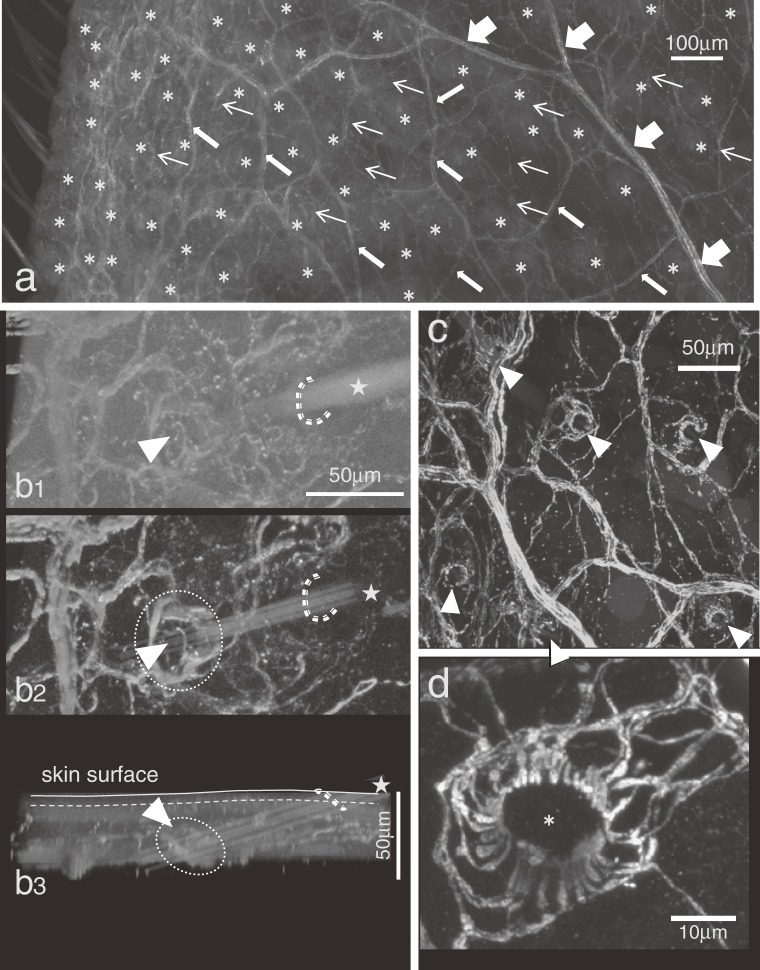

Figure 2.

PGP9.5-immunopositive dense nerve distribution in an auricular whole-mount tissue. a; Thick, middle and fine arrows; trunk, small and fine axon bundles. asterisks; all palisade endings in this rectangular area. b1; a view from the skin surface. A hair shaft comes out from the mouth of the follicle (dashed line) to the skin surface. b2; the same view as b1 but the surface layer was removed on the 3D-image. A palisade ending (circle) with a gap at a direction to the skin surface (arrowhead) could be seen. b3; a side view of b1. c; A view from subcutaneous side. Most palisade endings showed a gap respectively (arrowhead). All gaps were arranged to the same orientation. d; A palisade ending with entirely arranged lanceolate endings. A hair shaft should insert inside the circle (asterisk). The far side of this picture towards skin surface.

Innervation: General observation.

All axons from thick fibers in the nerve bundles to thin varicose fibers in the epidermis were well labelled by anti-PGP9.5 antibody and they showed a dense distribution in the auricular skin (Figs. 1d, 2a). A part of the axons were MBP-positive, thus they were myelinated (Fig. 4). Myelinated thick bundles came into at the basal cut end of the auricles and extended radially to the marginal area of the auricles showing several branching. Small nerve bundles firstly developed a rough network in the subcutaneous tissue, and then established a dense network, i.e., the dermal plexus, in which each of several hair follicles was surrounded by a network of nerve bundles (Fig. 2a). Finally, finer bundles originated from the plexus formed a finer network and then some single axons approached to the follicle to make a palisade ending (Fig. 2). All hair follicles without an exception had a palisade ending in the present studies. Merkel endings and lamellated corpuscles were scattered in the auricular skin (data not shown).

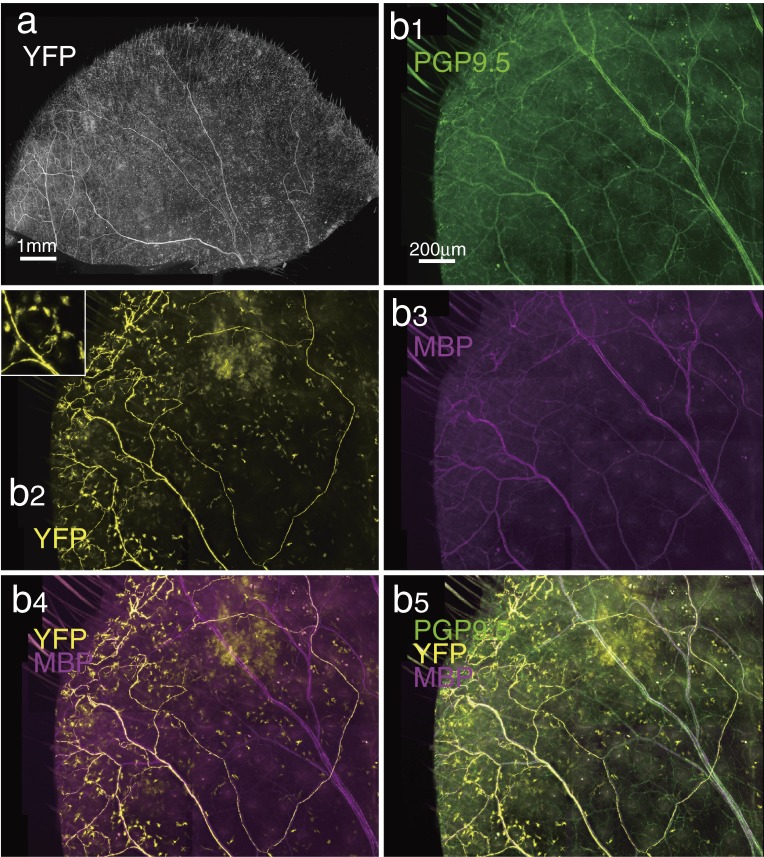

Figure 4.

Thy1-YFP-positive nerve distribution in auricular whole-mount tissue. a; A few axons and their terminals could be observed. (See Figs. 1 and 5.) b; Higher magnification of another auricule of the thy1-YFP transgenic mouse. b1, 2, 3; PGP9.5-, thy1-YFP- and MBP-positive nerve distribution, respectively. In addition to axons, a number of thy1-YFP-positive dendritic cells were distributed (insertion in b2). They were easily distinguished from axons. b4; All thy1-YFP-positive axons were MBP immunopositive. Only a part of MBP-immunopositive axons were thy1-YFP-positive. b5; PGP9.5-immunopositive nerve distribution covered all thy1-YFP-positive and/or MBP-immunopositive fibers and nerve endings.

Single palisade ending.

Each palisade ending was located beneath a sebaceous gland (Figs. 2, 3). Several myelinated fibers converged to the follicle from different directions. Beyond their myelin sheath, each fiber branched a few times and finally terminated as lanceolate endings in a fork-like shape. Individual lanceolate ending was a thickened and long axon terminal sandwiched mostly by two thin cell sheaths of the terminal Schwann cell (data not shown). A total of 10–32 lanceolate endings surrounded the hair shaft (n = 8) in a palisade arrangement. Occasionally a few circumferential lanceolate endings overlapped (Figs. 2, 3). Most palisade endings had only longitudinal lanceolate endings without circumferential lanceolate endings. On the other hand, a very few endings had only circumferential ones.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional reconstruction and axon-tracing analysis of one of popular palisade endings. PGP9.5-immunopositive innervation. a; A gap was one sixth of the palisade ending. This showed no circumferential lanceolate endings. Thick nerve bundles (thick arrows) surrounded each palisade ending and thinner bundles approached toward the ending (arrows). See higher magnification analysis of a square in b. b; Totally 32 individual lanceolate endings composed the palisade ending in irregular length. Vertical view made those lanceolate endings appear to be shorter than actual length. c; c1 is the same as b. Lanceolate endings were spread out into a flat plane in c2 and the number was counted. 32 lanceolate endings were converged to 28 axons but further centrally tracing was impossible because of intricate complexity of axons in a bundle in addition to low resolution of the image.

Most palisade endings had a gap in a circle of longitudinal lanceolate endings. The gap was 1/8–1/2 of the circle and usually faced to the epidermis, that is, superficial side of the hair root which canted over to the skin surface (Fig. 3). Thus, longitudinal lanceolate endings were generally distributed in the deeper side of the hair root at the resting position. These endings tended to form a population having those gaps in the similar direction on the dorsal auricular skin (Fig. 3).

Thy1-YFP-positive palisade endings.

Only a small portion of PGP9.5-immunopositive axons showed thy1-YFP-positivity in the skin (Fig. 4b). All of thy1-YFP-positive axons were MBP-positive, thus myelinated and NF200-immunopositive, thus Aβ-fibers. Only a part of MBP-immunopositive axons were thy1-YFP-positive.

Ten thy1-YFP-positive trunk axons were observed in a branch of the posterior auricular nerve at the basal middle edge of an auricular skin. All of them were fully traced to the endings individually by confocal three-dimensional analysis (Figs. 5, 6). Individual thy1-YFP-positive trunk axons innervated 4–54 hair follicles in each territory which showed different sizes of distribution area (Fig. 6). Only one of them showed a large isolated territory of terminals at the basal portion of the auricle. The others were distributed with overlaps with neighbouring territories in the marginal zone. All territories in the marginal zone included several follicles that were innervated by more than one afferents (Figs. 6, 7). One to 3 trunk axons were involved to form one palisade ending terminating as longitudinal lanceolate endings around hair follicles (Fig. 7f). Each terminal axon provided 1–5 lanceolate endings. They were distributed as a large-tooth combe. Lanceolate endings originated from different axon terminals infrequently showed crossover distribution (Figs. 5, 7f).

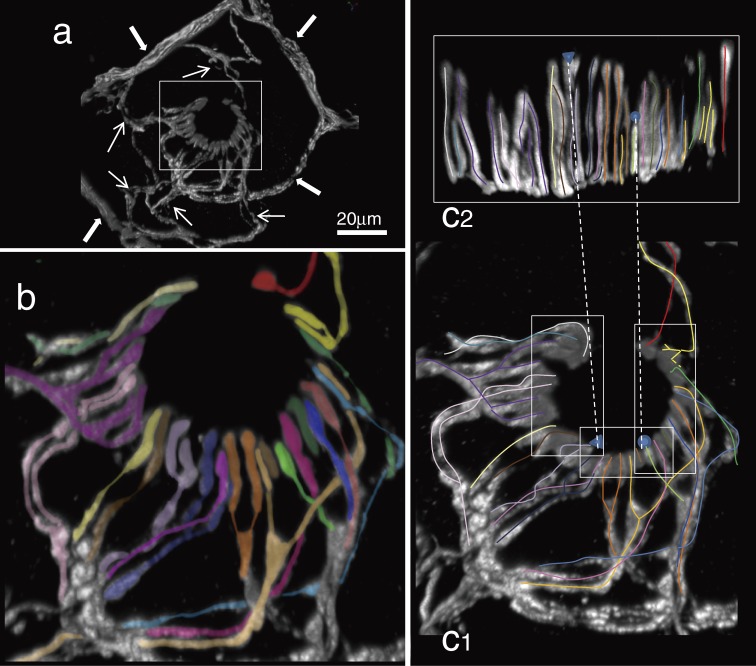

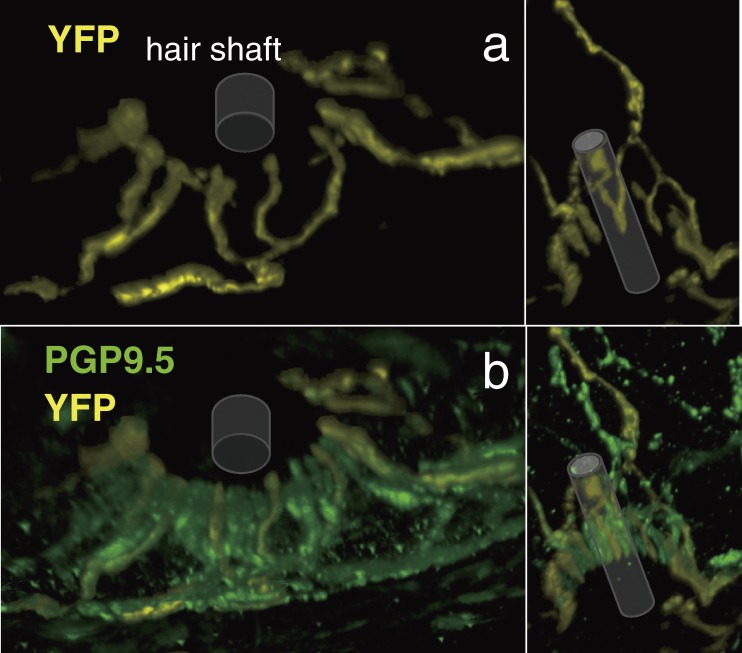

Figure 5.

A palisade ending in the thy1-YFP transgenic mouse. Views from an obliquely deep side (a) and a top side (b). Each cylinder indicates a part of the hair shaft (artificially input as about 3.5 µm-thick at the bottom). They are in front of the palisade endings in b. Only a few axon terminals were thy1-YFP-positive. PGP9.5-immunopositive but thy1-YFP-positive axon terminals could be observed between each of them.

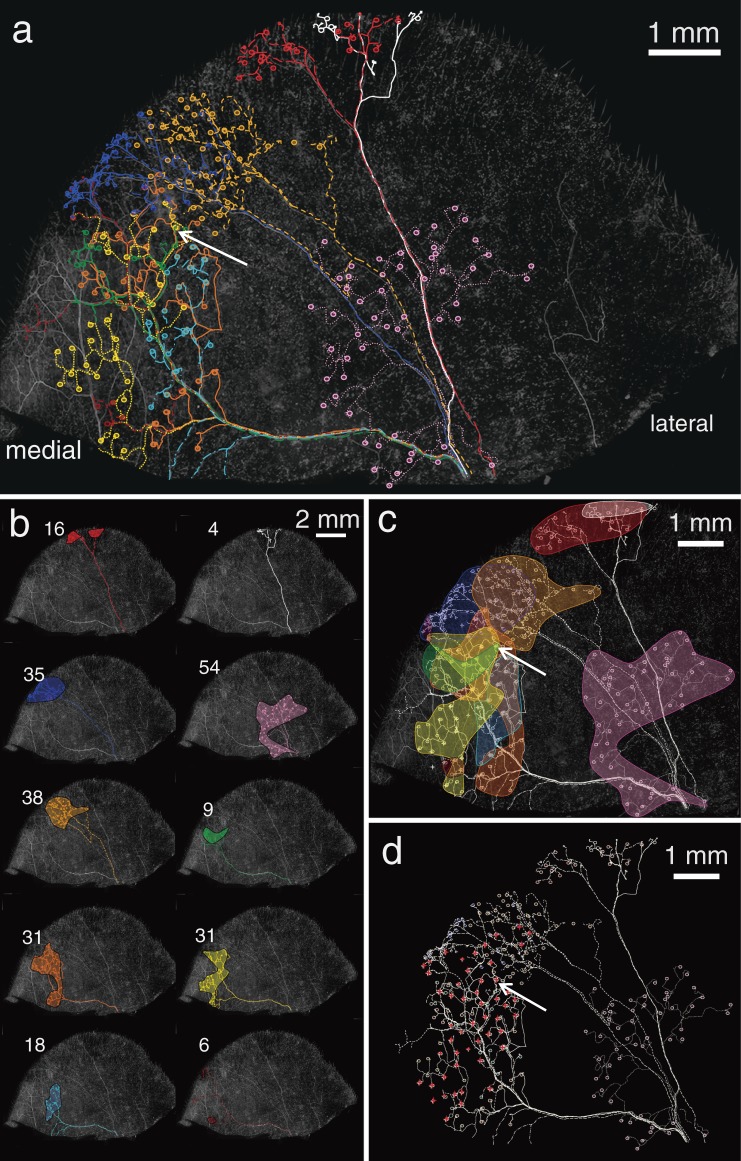

Figure 6.

Distribution of individual ten thy1-YFP-positive axons with endings. a; Different colour indicates different trunk axon (dashed line) with its endings (circles). A circle is one palisade ending in a follicle. b; Individual territories of those ten thy1-YFP-positive axons. Each number indicates individual number of palisade endings derived from the each axon. Some branches of them (red; 16, white; 4, green; 9, yellow; 31, sky blue; 18, dark red; 6) could not be traced to the end at the marginal zone of the auricle. c; Most areas except for one at the bottom (pink) overlapped each other. d; Palisade endings that were innervated more than one thy1-YFP-positive axons were highlighted (red stars). Arrows in a, c and d indicate a palisade ending which was innervated by three different trunk axons (see Fig. 7f).

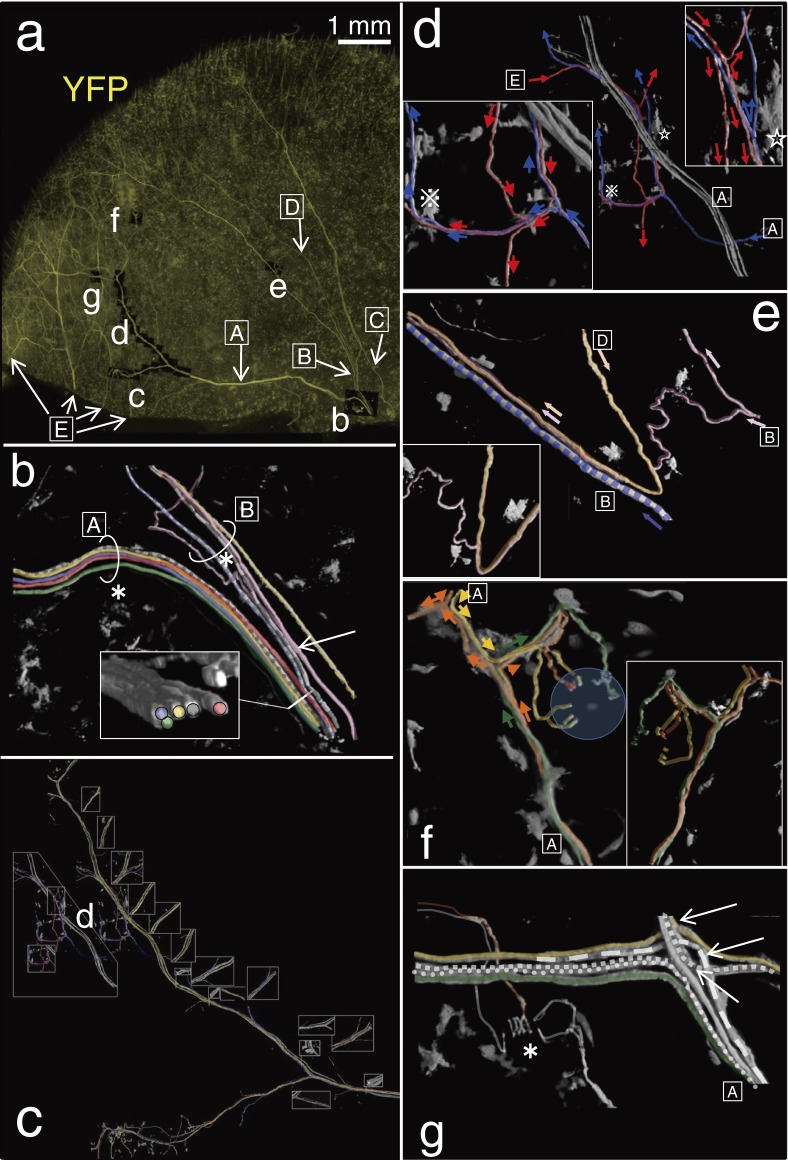

Figure 7.

Remarkable aspects on the tracing procedure of individual axons and endings. a; The same tissue as shown in Fig. 6. Overview of each cites of three-dimensional analysis in this figure (b–g). Squared capital letters (A–E) were nerve bundles. Bundle A and B were derived from a same bundle. Bundle C was immediately converged with a branch derived from B. Bundle D was a branch of bundle B. In addition to the bundles A–D, another thy1-YFP-positive nerve bundles (E) were observed at the medial bottom edge of the tissue. The bundle E was terminated showing overlaps with terminal areas mainly derived from bundle A. b; Different 9 thick thy1-YFP-positive axons were discriminated each other at the center bottom of the auricular skin. They were in a similar diameter. The bundle was divided into two bundles A and B. Immediately, an axon (pink) in bundle B showed the first division (arrow). After division of an axon (pink), bundle A and B included 5 and 6 trunk axons individually at the level of asterisks. c; Individual axons were properly traced at every pivotal point where axons often meandered and/or branched as shown in d–g. Every insertion indicates one of views from different aspects at the each point. See also one of those in higher magnification in d. d; Two different axons derived from bundle A (blue) and D (red) were traced. Arrows indicate distal directions. Both axons and their branches were intermingled with each other in small bundles. Thus, they included bidirectional afferents. Two different asterisks indicated thy1-YFP-positive dendritic cells as landmarks. e; Three different axons (orange, pink and purple arrows) that came from different directions but were derived from bundle B were finally packed into a bundle. Insertion is a back view without axon in purple. The axon in pink turned to distal direction at the back of the axon in orange at a hairpin curve. Thus, axons derived from the same bundle often showed breakaway after ramification, change directions and confluent of their courses. f; Different three axons (orange, yellow and green arrows) in bundle A supplied lanceolate endings of a palisade ending (circle). Lanceolate endings derived from each axon were distributed in small positions. A lanceolate ending derived from orange axon was between lanceolate endings from yellow axon. Insertion is a back view. g; Three axons showed ramifications at an intersection of nerve bundles (arrows). The other three axons went through. A palisade ending was innervated by different three axons. Asterisk indicates position of the hair shaft. Several dendritic cells surrounded the hair follicle.

Tracing of individual afferents made it clear that each of the small myelinated nerve bundles that comprise the network of the dermal nerve plexus included nerve fibers in both centrifugal and centripetal directions (Fig. 7d–g).

Discussion

One afferent is always connected to only one type of nerve ending.

In this study, we investigated detailed morphology of the palisade endings in the auricular skin by three-dimensional analysis and also with tracing methods using thy-1 gene-expressing YFP transgenic mouse. Only a part of myelinated innervation was thy1-YFP-positive in the transgenic mouse, and unmyelinated fibers were thy1-YFP-negative. A recent study demonstrated that 21–46% of innervation was thy1-YFP-positive.21) Such sparsely labelled neurons were useful to be traced as single axons in complicated skin innervation of the receptive field.

Although a certain number of myelinated afferents that originated from the dermal nerve plexus normally terminate as Merkel endings and lamellated corpuscles, while majority terminate as palisade endings, only palisade endings were thy1-YFP-positive in the auricular skin. Incidentally, Merkel endings at the level of the rete ridge collar in the mystacial vibrissa follicles of the same mice used in this study occasionally could be observed as well as a small part of the lanceolate endings at the level of the ring sinus and several palisade endings surrounding ordinal guard hairs distributed in the skin between vibrissae (data not shown). Those facts and the small proportion of thy1-YFP suggested that thy1-YFP positivity was specific to the lanceolate endings at least in the murine auricular skin. Furthermore, complete tracing of individual labelled axons in this study strongly suggested that one afferent is always connected to only one type of nerve ending.

Original afferents of a palisade ending.

In the murine skin, different layers of dense nerve plexus, subepidermal plexus/superficial dermal plexus, deep cutaneous plexus/dermal plexus and subcutaneous plexus, are distributed in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues, respectively.5) Axons originating from one of them come close to the final destination and terminate as different type of nerve endings. As for palisade endings, both longitudinal and circumferential lanceolate endings are generally said to be originated mainly from dermal plexus.2,12) In this study, clear discrimination could not be well pursued since subepidermal plexus was very close to the dermal plexus in such a thin tissue of the mouse auricle. Subepidermal plexus was mainly composed of unmyelinated fibers, so that we may just say that palisade endings were originated from dermal plexus. Our observations are consistent with previous studies.

Longitudinal lanceolate endings have been well demonstrated to originate from myelinated afferents and terminate as fork-like axon terminals. Each axon terminal is sandwiched by two pieces of thin cell sheath of terminal Schwann cells.1,8,10) These cells also made networks in connecting with each other by gap junction in lanceolate endings in the rat vibrissae.26,27) Axon and Schwann cell complex may work for mechanoacceptation and mechanotransduction in most mechanoreceptors.

Circumferential lanceolate endings in all types of hair follicles except for lanceolate endings in vibrissa hairs have been considered to originate from unmyelinated afferents.28) However, our observation indicated that they also originate from myelinated fibers in auricular skin since they were positive to both thy1-YFP and MBP. In addition, PGP9.5-immunopositive innervations showed unmyelinated nerve distribution surrounding near palisade endings in both guard and vellus hairs and vibrissae.13,28) Most of unmyelinated nerves showed varicose appearance. PGP9.5-positive but Thy1-YFP-negative lanceolate endings might possibly originate from myelinated afferents that were incidentally negative thy1-YFP expression. Further tracing study will be required to clear it.

Numbers of palisade endings and lanceolate endings to a trunk afferent.

Ten to 32 PGP9.5-immunopositive thick lancet-like axon terminals and their myelinated afferents were counted in individual palisade endings. These observations are largely in agreement with earlier studies that showed 4–30 myelinated afferents in individual palisade endings.13,18,29,30) The difference in the number may depend on the size of follicle in different animals. On the other hand, our tracing analysis of individual thy1-YFP-positive afferents to their endings showed for the first time that individual palisade endings might be innervated by at least 2–4 different trunk afferents. The reason for this is that most palisade endings were innervated by 1–3 thy1-YFP-positive trunk afferents in addition to singly innervated by PGP9.5-immunopositive lanceolate endings.

Numbers and characteristics of neurons that innervate a palisade ending.

The hair type found in murine skin of the back is distinguished into four (guard, awl, auchene and zigzag) on the basis of the length of hair shaft, the number of medulla cells and the presence of kinks in the shaft.31) Zigzag hair follicles are innervated by both C- and Aδ-low-threshold mechanoreptors (LTMRs), awl/auchene hairs by Aβ-, Aδ- and C-LTMRs and guard hairs by Aβ-LTMRs.32) The longitudinal laceolate endings of the zigzag and awl/auchene hair follicle suggest innervations by different neurons. In this study, even a palisade ending of the guard hair was also always innervated by 1–3 thy1-YFP-positive different trunk axons. In addition, each of thy1-YFP-positive axons showed the first ramification close to the terminal area. Further investigations are needed to show if each thy1-YFP-positive axon originates from an individual neuron. If that is the case, each palisade ending would be innervated by at least 2–4 primary sensory neurons.

This study is the first clear demonstration of complete trajectories of individual Aβ-fibers that constitute a single palisade ending in non-vibrissal hairs. Although such multiple innervation was shown in mouse dorsal skin by Li et al. (2011),32) Aβ-fibers of different cell origin were not distinguishable from one another by their labeling technique. On the other hand, this study appears to lack information concerning interdigitation among C, Aδ- and Aβ-axon terminals as demonstrated by Li et al. (2011).32)

Morphology and function of palisade endings.

Such interdigitating manner of lanceolate endings may suggest not only innervations by multiple neurons on a follicle but also a possibility of responses to hair shaft movements in wider directions than a restricted distribution. The responsiveness may be facilitated by that single afferent innervating considerable number of hair follicles at the same time. A single thy1-YFP-positive axon terminated in various directions on the multiple palisade endings.

On the other hand, most of individual palisade endings in the murine auricular skin showed a gap in longitudinal lanceolate ending arrangements. This is consistent with previous studies in the murine body hairy skin.13) Palisade endings have been regarded to evoke nerve firings when the hairs were bristled up.33,34) According to our observations, lanceolate endings might ordinarily form a gap in the direction to which the hair goes forward during the hair protraction. Those gaps of lanceolate endings were found at the similar orientation in neighbouring hair follicles. In addition to the possibility of innervations by multiple sensory neurons on every palisade ending, these results may suggest that palisade endings would represent an ideal structure to be exquisitely sensitive to hair bristling/protraction although their directional discrimination may be poor.

A previous study showed that 150–579 corpuscles were distributed in the murine auricular skin and that at least 20 and at most 40–60 corpuscles might be innervated by a single myelinated afferent.20) Another study on the cat finger tip showed that more than 150 Merkel-nerve complexes of a touch dome converged to a single myelinated afferent.25) In this study, individual thy1-YFP-positive axons innervated 4–54 palisade endings. All of those observations confirmed previous neurophysiological studies that suggested each of single trunk afferents should have a restricted receptive field in which the afferent innervated only one kind of multiple nerve endings.33) However, in any cases, it is still uncertain whether each of trunk afferents in the tissue originated from a separate primary sensory neuron unless a single neuron is successfully traced from the cell body to the nerve ending.

Most palisade endings in the murine auricular skin showed complicated interdigitating distribution of lanceolate endings. And individual palisade endings may be innervated by multiple neurons. Most of small myelinated nerve bundles in the dermal plexus included both bidirectional afferents. Functions depend on those morphological characteristics of palisade endings are still uncertain. Further histological investigation supported by electrophysiology will required to well understand touch sense.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Dr. Kunihiko Suzuki for the occasion of his 80th birthday with sincere appreciation for his constant support and encouragement for many years. We express gratitude to Raya Eilam (Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel) for gift of the fixed transgenic animals. We express appreciation to Marie Takahashi and Daichi Kuroda for their excellent experimental assistance. This study was supported by a Grant-in Aid for Research of Meiji University of Integrative Medicine [Project II-2-1;2010 “Morphological analysis of “comfortable touch sensation””].

Abbreviations

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- NF200

neurofilament 200

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- PGP9.5

protein gene product 9.5

- thy1

thymus cell antigen 1

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

References

- 1).Andres, K.H. and von Düring, M. (1973) Morphology of cutaneous receptors. In Handbook of Sensory Physiology (eds. Autrum, H., Jung, R., Kiewebsteub, W.R. and MacKay, D.M.). Springer, Berlin, New York, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2).Rice F.L., Munger B.L. (1986) A comparative light microscopic analysis of the sensory innervation of the mystacial pad. II. The common fur between the vibrissae. J. Comp. Neurol. 252, 186–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Millard C.L., Woolf C.J. (1988) Sensory innervation of the hairs of the rat hind-limb: A light microscopic analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 277, 183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Fundin B.T., Arvidsson J., Aldskogius H., Johansson O., Rice S.N., Rice F.L. (1997) Comprehensive immunofluorescence and lectin binding analysis of intervibrissal fur innervation in the mystacial pad of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 385, 185–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Botchkarev V.A., Elechmuller S., Johansson O., Paus R. (1997) Hair cycle-dependent plasticity of skin and hair follicle innervations in normal murine skin. J. Comp. Neurol. 386, 379–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Peters E.M.J., Botchkarev V.A., Muller-Rover S., Moll I., Rice F.L., Paus R. (2002) Developmental timing of hair follicle and dorsal skin innervation in mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 488, 28–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Vincent S.B. (1913) The tactile hair of the white rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 23, 1–34 [Google Scholar]

- 8).Andres K.H. (1966) Über die Feinstruktur der Rezeptoren an Sinushaaren. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 75, 339–365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Gottschaldt K.M., Iggo A., Young D.W. (1973) Functional characteristics of mechanoreceptors in sinus hair follicles of the cat. J. Physiol. 235, 287–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Halata Z., Munger B.L. (1980) Sensory nerve endings in rhesus monkey sinus hairs. J. Comp. Neurol. 192, 645–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Munger B.L., Halata Z. (1983) The sensory innervation of primate facial skin. I. Hairy skin. Brain Res. 286, 45–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Halata Z. (1993) Sensory innervation of the hairy skin (light- and electronmicroscopic study). J. Invest. Dermatol. 101, 75S–81S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Rice F.L., Kinnman E., Aldskogius H., Johansson O., Arvidsson J. (1993) The innervation of the mystacial pad of the rat as revealed by PGP 9.5 immunofluorescence. J. Comp. Neurol. 337, 366–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Ebara S., Kumamoto K., Matsuura T., Mazurkiewicz J.E., Rice F.L. (2002) Similarities and differences in the innervation of mystacial vibrissal follicle-sinus complexes in the rat and cat: a confocal microscopic study. J. Comp. Neurol. 449, 103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Iggo A., Ogawa H. (1977) Correlative physiological and morphological studies of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors in cat's glabrous skin. J. Physiol. 66, 275–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Luo W., Enomoto H., Rice F.L., Milbrandt J., Ginty D.D. (2009) Molecular identification of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors and their developmental dependence on ret signalling. Neuron 64, 841–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Biemesderfer D., Munger B.L., Binck J., Dubner R. (1978) The pilo-Ruffini complex: a non-sinus hair and associated slowly-adapting mechanoreceptor in primate facial skin. Brain Res. 24, 197–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Weddell G., Pallie W. (1955) Studies on the innervation of skin. II. The number, size and distribution of hairs, hair follicles and orifices from which the hairs emerge in the rabbit ear. J. Anat. 89, 175–188 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Weddell G., Pallie W., Palmer E. (1955) Studies on the innervation of skin. I. The origin, course and number of sensory nerves supplying the rabbit ear. J. Anat. 89, 162–174 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).McLoughlin H., Fitzgerald M.J. (1989) Encapsulated nerve endings in murine dorsal ear skin. J. Anat. 167, 215–223 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Gordon J.W., Chesa P.G., Nishimura H., Rettig W.J., Maccari J.E., Endo T., Seravalli E., Seki T., Silver J. (1987) Regulation of Thy-1 gene expression in transgenic mice. Cell 50, 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Feng G., Mellor R.H., Bernstein M., Keller-Peck C., Nguyen Q.T., Wallace M., Nerbonne J.M., Lichtman J.W., Sanes J.R. (2000) Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 28, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Cheng C., Guo G.F., Martinez J.A., Singh V., Zochodne D.W. (2010) Dynamic plasticity of axons within a cutaneous milieu. J. Neurosci. 30, 14735–14744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Aharoni R., Arnon R., Eilam R. (2005) Neurogenesis and neuroprotection induced by peripheral immunomodulatory treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. 25, 8217–8228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Ebara S., Kumamoto K., Baumann K.I., Halata Z. (2008) Three-dimensional analyses of touch domes in the hairy skin of the cat paw reveal morphological substrates for complex sensory processing. Neurosci. Res. 61, 159–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Takahashi-Iwanaga H. (2000) Three-dimensional microanatomy of longitudinal lanceolate endings in rat vibrissae. J. Comp. Neurol. 426, 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Takahashi-Iwanaga H., Nio-Kobayashi J., Habara Y., Furuya K. (2008) A dual system of intercellular calcium signaling in glial nets associated with lanceolate sensory endings in rat vibrissae. J. Comp. Neurol. 510, 68–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Mosconi T.M., Rice F.L., Song M.J. (1993) Sensory innervation in the inner conical body of the vibrissal follicle-sinus complex of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 328, 232–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Fitzgerald M.J., Lavelle S.M. (1966) Response of murine cutaneous nerves to skin painting with methylcholanthrene. Anat. Rec. 154, 617–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Miller S., Weddell G. (1966) Mechanoreceptors in rabbit ear skin innervated by myelinated nerve fibres. J. Physiol. 187, 291–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Driskell R.R., Giangreco A., Jensen K.B., Mulder K.W., Watt F.M. (2009) Sox2-positive dermal papilla cells specify hair follicle type in mammalian epidermis. Development 136, 2815–2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Li L., Rutlin M., Abraira V.E., Cassidy C., Kus L., Gong S., Jankowski M.P., Luo W., Heintz N., Koerber H.R., Woodbury C.J., Ginty D.D. (2011) The functional organization of cutaneous low-threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell 147, 1615–1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Brown A.G., Iggo A. (1967) A quantitative study of cutaneous receptors and afferent fibres in the cat and rabbit. J. Physiol. 193, 707–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Adrian E.D. (1930) The effects of injury on mammalian nerve fibres. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B 106, 596–618 [Google Scholar]