Abstract

Study Objective

To examine whether the known association between early pubertal breast maturation and insulin sensitivity (SI) is mediated by adiposity.

Design

Cross-sectional analyses, Setting: Observational study examining the roles of environment, diet, and obesity on puberty

Participants

379 girls with a mean age, 7.03 years; 62% were white and 29% black

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Pubertal development was assessed via physical examination and adiposity by body mass index Z score (BMI Z) and waist-to-height ratio. Fasting blood samples were obtained for insulin and glucose concentrations. SI was calculated with the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI). Analysis of variance and Sobel’s test was used to assess mediation.

Results

Fifty-five girls were pubertal (Tanner 2 breast). Breast maturation was inversely associated with SI (p=.005) and positively associated with BMI Z (p<.001) and waist-to-height ratio (p<.001). The effect of breast maturation on SI was no longer significant (p=.41) after adjusting for the effect of BMI Z, which remained significant (p<.001). Similar results were obtained when waist-to-height ratio replaced BMI Z in the models. Mediation analyses demonstrated that 75% of the association between breast maturation and SI is mediated by adiposity.

Conclusions

In girls, decreased SI during early puberty is largely mediated by total and visceral adiposity.

Keywords: puberty, insulin resistance, obesity

INTRODUCTION

The peripubertal period is a time of change in body composition and sensitivity to insulin. Higher body fat content is associated with earlier pubertal maturation in girls, and earlier puberty is associated with higher body fat content later in life (1). Pubertal maturation is also associated with a decrease in insulin sensitivity (SI) (2, 3). Obesity is widely recognized as a risk factor for insulin resistance (i.e., decreased SI) as well as for development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Changes in SI during pubertal maturation have been previously studied (2–5). SI peaks just before the onset of puberty, reaches a nadir at mid-puberty, and approaches prepubertal levels near the end of maturation (3, 4). Mechanisms for puberty-related changes in SI remain unknown; hypotheses include changes in growth hormone, sex-steroid hormones, and body composition. Some propose that the decrease in SI is not related to adrenal or gonadal steroids because these hormones rise and remain elevated, while SI improves only later in puberty (3, 4, 6). Changes in total body fat and fat distribution have also been refuted based on similar arguments that the increase in fat accumulation persists or increases further.

Adiposity, in particular central adiposity, is associated with decreased SI among women (7). The relationship between adiposity and SI is also present in prepubertal children (8). Mechanisms by which adipose tissue impacts SI are likely multifactorial, involving communication between various endocrine axes including growth hormone, steroid hormones, and adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin.

It is unclear to what extent changes in SI can be attributed solely to increased adiposity during development. This is an important concept given the rise in obesity in pediatric populations. The increased prevalence of obesity is considered the cause for the upsurge of T2DM in the United States. Greater degrees of adipose accumulation during the pubertal transition may cause an even greater decrease in SI and a heightened risk of developing impaired glucose tolerance or T2DM. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the mediating role of adiposity on the association between early pubertal maturation and SI among school-aged girls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The study sample included 379 school-aged girls enrolled in a longitudinal study evaluating the roles of environment, diet, and obesity on puberty. This cross-sectional analysis presents data from the initial study visit only. Participants were recruited from elementary schools in Cincinnati, Ohio. Girls entered the study at age 6–7 years and were assessed every 6 months, either at their school or at the Clinical Translational Research Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Girls were instructed to fast after 22:00 the night prior to their visit and arrived the following morning between 07:30 and 09:30. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained. Race and ethnicity were self-reported by the child’s parents.

Measures

Anthropometry

Height was obtained by a stadiometer (Shorr Productions, Olney, MD) and weight by a digital scale (Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), with the participant wearing standardized clothing and no shoes. Waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus with a fiberglass measuring tape by trained staff. Body mass index (BMI) Z score was calculated using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth curve reference data (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/data_tables.htm) and is a measure of total adiposity. Waist-to-height ratio (central adiposity) was calculated as waist circumference (cm) divided by height (cm) (9).

Pubertal maturation (breast)

Maturation assessment was completed by trained clinicians using both observation and palpation of the breasts for breast maturation. Pubic hair was assessed as well. For these analyses, pubertal maturation of the breast is used as it is typically the first sign of puberty in girls (10). Methods for the maturation assessment are described in further detail elsewhere (11). Absence (prepubertal) or presence (pubertal) of breast maturation defined pubertal status.

Insulin sensitivity

Glucose and insulin concentrations were measured in serum. The qualitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) was used to calculate SI (QUICKI = 1/[log(I0) + log(G0)], where I0= fasting insulin and G0= fasting glucose) (12, 13). QUICKI is a simple and robust method to assess SI and is highly correlated with SI as measured by the glucose clamp, which is the gold standard (12). Fasting insulin and glucose are thought to be highly reflective of SI for girls in early stages of pubertal development (14).

Statistical analyses

Distributions of QUICKI, BMI Z and WHR were assessed and found to be normal. Three hundred thirty girls (87%) had complete laboratory data. Imputation of missing data for SI was done by multiple imputation technique using Solars®, and five sets of imputed data for the insulin and glucose concentrations were generated. Imputation was done to maximize efficiency and minimize potential bias. Analysis of variance was applied to each imputed data set to assess the overall association between pubertal maturation and SI. Final results were summarized from estimates of the five imputed data sets by accounting for between-imputation variations using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Separate models were used to test for mediation using total and central adiposity with Sobel’s test (15). The directionality between the variables in the models was formulated based on biological plausibility and prior literature.

RESULTS

The majority of girls were non-Hispanic white (61.5%) and prepubertal (85.5%), and all had normal glucose concentrations. A range of adiposity was evident, with a mean BMI of 16.33 (± 2.70). Additional descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics for participants (N=379) and descriptive statistics of the key variables

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Age (y) | 7.03 (0.63) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 233 (61.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 130 (34.3) | |

| Hispanic | 12 (3.2) | |

| Asian | 3 (0.8) | |

| Tanner breast stage | ||

| 1 | 324 (85.5) | |

| 2 | 55 (14.5) | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 84.75 (8.01) | |

| Fasting insulin (μU/mL) | 12.39 (9.36) | |

| Insulin sensitivity (QUICKI) | 0.15 (0.01) | |

| Weight (kg) | 25.84 (6.02) | |

| Height (cm) | 123.50 (7.09) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 55.52 (2.70) | |

| BMI | 16.33 (2.70) | |

| BMI Z score | 0.34 (1.10) | |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.45 (0.04) | |

Note: BMI = body mass index (kg/meters2); QUICKI = quantitative insulin sensitivity check index.

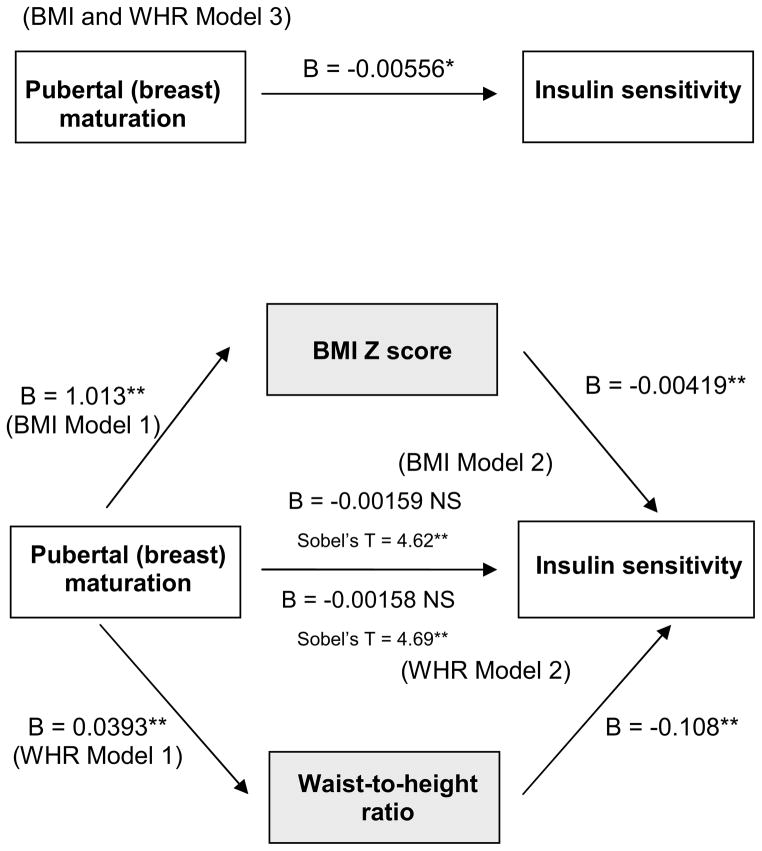

Controlling for age, race, and ethnicity, early pubertal maturation (breast development) was inversely associated with SI (B= −0.0056, p<.01). After adding total adiposity (BMI Z) to the model, the association between pubertal maturation and SI was no longer significant; similar results were achieved after adding central adiposity (waist-to-height ratio) to the model (Table 2, Figure 2). Mediation analyses revealed that BMI Z and waist-to-height ratio were significant mediators (>75%) of the association between early pubertal breast maturation and SI (Sobel’s T = 4.62 and 4.69, respectively). Race did not moderate either the association between early pubertal maturation and SI or the mediational relationships.

Table 2.

Mediation analyses

| Mediation Analyses with BMI Z (total adiposity) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Beta | SD | T Value | P Value | ||

| Model 1 | BMI Z | ||||

|

| |||||

| Breast maturation | 1.013 | 0.166 | −6.09 | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Model 2 | Insulin sensitivity (includes effects from BMI Z) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Breast maturation | −0.00159 | 0.00192 | 0.83 | 0.41 | |

| BMI Z | −0.00419 | 0.000592 | −7.08 | <.0001 | |

| Sobel | 4.62 | <.0001 | |||

|

| |||||

| Model 3 | Insulin sensitivity (QUICKI) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Breast maturation | −0.00556 | 0.00197 | 2.81 | 0.0052 | |

|

| |||||

| Mediation Analyses with WHR (central adiposity) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Beta | SD | T Value | P Value | ||

|

| |||||

| Model 1 | WHR | ||||

|

| |||||

| Breast maturation | 0.0393 | 0.006 | −6.57 | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Model 2 | Insulin sensitivity (includes effects from WHR) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Breast maturation | −0.00158 | 0.00194 | 0.81 | 0.42 | |

| WHR | −0.108 | 0.0162 | −6.69 | <.0001 | |

| Sobel | 4.69 | <.0001 | |||

|

| |||||

| Model 3 | Insulin sensitivity (QUICKI) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Breast maturation | −0.00556 | 0.00197 | 2.81 | 0.0052 | |

Note: BMI Z = body mass index Z score; QUICKI = Qualitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index; WHR = waist-to-height ratio

Figure 2.

Results of Analysis of variance

All models adjusted for age, race, and ethnicity.

*p<.01, **p<.0001

Note: NS= nonsignificant; B = Beta; BMI = body mass index, WHR = waist to height ratio

DISCUSSION

In these cross-sectional analyses, we demonstrated that total and central adiposity explain a majority (>75%) of changes in SI during early pubertal maturation. This important finding provides a clear link between early pubertal maturation, adiposity, and SI and exemplifies how pubertal development encompasses more than changes in secondary sexual characteristics. Race was not found to be a moderator.

Changes in SI during pubertal maturation have been described previously. Several studies have demonstrated that girls experience an increase in adiposity during pubertal maturation (17, 18). The biologic mechanisms and functional etiology for decreased SI are unclear. Hypotheses suggest that decreased SI (i.e., relatively higher insulin concentrations) may facilitate maximal linear growth through the effects of insulin on growth during puberty and that decreased SI may be protective against hypoglycemia during puberty, a period of high metabolic demands. Regardless, the findings indicate potential communication between gonadal hormones, adipose tissue, and glucose homeostasis mechanisms. Metabolic regulation of puberty, adiposity, and glucose metabolism may occur through adipokines, glucocorticoids, growth hormone, or other neuroendocrine mechanisms. For example, Bouhours-Nouet demonstrated that obese prepubertal children have a greater insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) response to growth hormone, with IGF-1 reflecting how adiposity interacts with other hormones to impact metabolism (19). The multifactorial hormonal influence on SI is also evident in leptin and adiponectin concentrations, which are further impacted by gonadal steroid hormones (20); the ratio of these adipokines is strongly associated with SI (21).

Although the current study found that the majority of the association between SI and early pubertal maturation is explained by adiposity, there are other studies that have alternative viewpoints. Adam and colleagues noted that SI at an early age is an important independent predictor for fat mass gain later in life among Hispanic adolescents (16). In other words, SI predicted adiposity in their study, rather than adiposity predicting SI as we have proposed. In addition, Moran studied 357 healthy children at varying stages of puberty and noted that insulin resistance was related to BMI, triceps skinfold thickness, and waist circumference, but concluded that these factors did not completely explain the changes in SI that throughout the different stages of puberty (3). In a longitudinal analysis of changes in SI among black and white youth during puberty, Ball and colleagues noted that the change in SI across Tanner stages as a quadratic effect remained significant after adjusting for fat mass (from Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry), sex, and baseline age. These data suggest that something beyond fat mass, or in addition to fat mass, may explain the changes in SI during puberty (4). The current study provides a glimpse only into the early stage of pubertal development (Tanner 1 to 2) so the findings cannot be directly compared to those studies evaluating changes in SI across all stages of puberty. It may be that during this early stage of development, adiposity plays a greater role in the changes in SI, compared to later stages in development.

The association of changes in adiposity during early pubertal maturation with a decrease in SI remains provocative. Of note, the girls in this cohort were observed after the obesity epidemic in the United States, and it is uncertain whether any subsequent metabolic consequences may be found. Prepubertal obesity may be an additional risk factor for impaired glucose tolerance or T2DM in mid- to late puberty (22). Decreasing SI exposes the body to higher insulin concentrations. Insulin stimulates ovarian stromal production of gonadal hormones, including estradiol and testosterone. The result of a potentially greater exposure to insulin before and during puberty in terms of ovarian stimulation is unclear, but there may be implications for adverse reproductive health outcomes, such as polycystic ovary syndrome. Further, because insulin receptors exist in many tissues in the body, the impact of decreased SI during pubertal maturation can be extensive.

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design because causality cannot be established. The limited race and ethnic representation may impact the power to detect differences by race/ethnicity and ultimately the generalizability of findings. Finally, use of BMI and waist-to-height ratio as measures of adiposity rather than more precise measures of fat mass may have resulted in limited precision needed to clarify the relationships among the variables studied.

It is unclear whether the change in SI during early pubertal maturation results from an increase in adiposity or whether an increase in adiposity results from insulin resistance. Based on the current study’s findings, girls with increasing adiposity and decreasing SI early in puberty are likely to continue to accumulate additional fat mass. As delineated in our study, relationships between early pubertal maturation, adiposity, and SI at a mean age of 7 years may forecast significant long-term effects of increasing adiposity and risk for T2DM in young women.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U 01ES016003 from the NIH, UL1 RR026314 from the National Center for Research Resources, and K12 HD051953 from NIH/Office for Research on Women’s Health (Dr. Hillman).

Abbreviations

- SI

insulin sensitivity

- BMI Z

body mass index Z score

- QUICKI

quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Author contributions: Drs. Hillman, Huang, Pinney and Biro designed and conducted the study. Dr. Huang completed the statistical analyses. All authors interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaplowitz PB. Link between body fat and the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):S208–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813F. Epub 2008/02/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goran MI, Gower BA. Longitudinal study on pubertal insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2001;50(11):2444–50. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2444. Epub 2001/10/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran A, Jacobs DR, Jr, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Prineas R, Luepker R, et al. Insulin resistance during puberty: results from clamp studies in 357 children. Diabetes. 1999;48(10):2039–44. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.2039. Epub 1999/10/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball GD, Huang TT, Gower BA, Cruz ML, Shaibi GQ, Weigensberg MJ, et al. Longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and beta-cell function during puberty. J Pediatr. 2006;148(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.059. Epub 2006/01/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caprio S, Plewe G, Diamond MP, Simonson DC, Boulware SD, Sherwin RS, et al. Increased insulin secretion in puberty: a compensatory response to reductions in insulin sensitivity. J Pediatr. 1989;114(6):963–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80438-x. Epub 1989/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch CA, Clemons P, Sperling MA. Puberty decreases insulin sensitivity. J Pediatr. 1987;110(3):481–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80522-x. Epub 1987/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Bjorntorp P. The quantitative relationship between “the metabolic syndrome” and abdominal obesity in women. Obes Res. 1994;2(4):372–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00077.x. Epub 1994/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arslanian S, Suprasongsin C. Insulin sensitivity, lipids, and body composition in childhood: is “syndrome X” present? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(3):1058–62. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772576. Epub 1996/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weili Y, He B, Yao H, Dai J, Cui J, Ge D, et al. Waist-to-height ratio is an accurate and easier index for evaluating obesity in children and adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(3):748–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.601. Epub 2007/03/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biro FM, Galvez MP, Greenspan LC, Succop PA, Vangeepuram N, Pinney SM, et al. Pubertal assessment method and baseline characteristics in a mixed longitudinal study of girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e583–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3079. Epub 2010/08/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron AD, Follmann DA, Sullivan G, et al. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2402–10. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6661. Epub 2000/07/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muniyappa R, Lee S, Chen H, Quon MJ. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(1):E15–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00645.2007. Epub 2007/10/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam TC, Hasson RE, Lane CJ, Davis JN, Weigensberg MJ, Spruijt-Metz D, et al. Fasting indicators of insulin sensitivity: effects of ethnicity and pubertal status. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):994–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1593. Epub 2011/03/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobel ME. In: Sociological Methodology. Leinhart S, editor. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam TC, Toledo-Corral C, Lane CJ, Weigensberg MJ, Spruijt-Metz D, Davies JN, et al. Insulin sensitivity as an independent predictor of fat mass gain in Hispanic adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2114–5. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0833. Epub 2009/08/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulding A, Taylor RW, Gold E, Lewis-Barned NJ. Regional body fat distribution in relation to pubertal stage: a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry study of New Zealand girls and young women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(4):546–51. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.4.546. Epub 1996/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vink EE, van Coeverden SC, van Mil EG, Felius BA, van Leerdam FJ, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Changes and Tracking of Fat Mass in Pubertal Girls. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.366. Epub 2009/10/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouhours-Nouet N, Gatelais F, Boux de Casson F, Rouleau S, Coutant R. The insulin-like growth factor-I response to growth hormone is increased in prepubertal children with obesity and tall stature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):629–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2631. Epub 2006/11/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horlick MB, Rosenbaum M, Nicolson M, Levine LS, Fedun B, Wang J, et al. Effect of puberty on the relationship between circulating leptin and body composition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2509–18. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6689. Epub 2000/07/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oda N, Imamura S, Fujita T, Uchida Y, Inagaki K, Kakizawa H, et al. The ratio of leptin to adiponectin can be used as an index of insulin resistance. Metabolism. 2008;57(2):268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.09.011. Epub 2008/01/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison JA, Glueck CJ, Horn PS, Schreiber GB, Wang P. Pre-teen insulin resistance predicts weight gain, impaired fasting glucose, and type 2 diabetes at age 18–19 y: a 10-y prospective study of black and white girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(3):778–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.3.778. Epub 2008/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]