Abstract

Cognitive operations requiring working memory rely on the activity of neurons in areas of the association cortex, most prominently the lateral prefrontal cortex. Human imaging and animal neurophysiological studies indicate that this activity is shaped by learning, though much is unknown about how much training alters neural activity and cortical organization. Results from non-human primates demonstrate that prior to any training in cognitive tasks, prefrontal neurons respond to stimuli, exhibit persistent activity after their offset, and differentiate between matching and non-matching stimuli presented in sequence. A number of important changes also occur after training in a working memory task. More neurons are recruited by the stimuli and exhibit higher firing rates, particularly during the delay period. Operant stimuli that need to be recognized in order to perform the task elicit higher overall rates of responses, while the variability of individual discharges and correlation of discharges between neurons decrease after training. New information is incorporated in the activity of a small population of neurons highly specialized for the task and in a larger population of neurons that exhibit modest task related information, while information about other aspects of stimuli remains present in neuronal activity. Despite such changes, the relative selectivity of the dorsal and ventral aspect of the lateral prefrontal cortex is not radically altered with regard to spatial and non-spatial stimuli after training. Collectively, these results provide insights on the nature and limits of cortical plasticity mediating cognitive tasks.

Keywords: prefrontal cortex, cognitive training, monkey, neurophysiology, neuron

1. INTRODUCTION

Working memory and higher cognitive functions that depend on it, such as planning and abstract thought, rely on the activity of cortical neurons in the lateral prefrontal cortex [1]. Individual prefrontal neurons exhibit neural correlates of working memory in the form of sustained discharges that represent the properties of remembered stimuli [2–4]. Neuronal responses vary depending on the context of the task subjects have been trained to perform, so that identical stimuli may elicit very different responses [5–8]. The influence of the task itself is often unclear and it cannot be easily determined if activity exhibited in the context of various tasks was always present in the prefrontal cortex or emerged as a result of learning. Even in studies where highly specific activity for the demands of the task has been found [9, 10], how this new information interacts with pre-existing information is not immediately apparent.

In recent years, imaging and neurophysiological studies have offered insights about the effects of training on the prefrontal cortex [11, 12]. Experiments have investigated how the prefrontal cortex responds to stimuli prior to and after training to perform a task, and how new information is integrated in neural circuits while simultaneously maintaining the ability to perform previously learned behaviors. The ability to adapt to new demands is a foundation of intelligent behavior and understanding the effects of training is of obvious value. At the same time, it has become apparent that training in working memory can generalize across tasks and can confer tangible benefits as a means of cognitive rehabilitation or clinical treatment [13, 14].

This article reviews the effects of training on cortical activity. Human imaging studies provide a macroscopic view of changes elicited by training and their applications. Recordings in non-human primates (which will be the main focus of this review) allow for a deeper understanding of the properties and organization of the prefrontal cortex and how these are altered by working memory training. Specific effects on neuronal firing rate, discharge variability, stimulus selectivity, and decoding of information will be discussed.

2. IMAGING STUDIES

A number of human fMRI studies have examined the effects of training on various tasks. An increase in BOLD activation has been most commonly observed in the prefrontal cortex after training to perform working memory tasks, such as n-back, and span-board tasks, that require the maintenance of multiple items in memory [11, 15–18]. Increased prefrontal activation has also been observed after training in other cognitive tasks [19, 20]. However some human fMRI studies have reported decreased BOLD activation after training in tasks that require object, visuospatial, and verbal working memory [21–25]. A possible interpretation for this apparent discrepancy is that reduced activation is seen in tasks where training allows for improved strategies that increase efficiency and take advantage of priming, or otherwise automating performance without the need to explicitly consider the task rules, consequently reducing demands for prefrontal activation [26]. On the other hand, increased prefrontal activation is observed in tasks where training involves improvement in the duration or capacity of working memory. Enhanced BOLD activation has been further associated with increased density of dopamine D1 receptors [15].

The impact of training on brain activation has received increased attention in recent years because some training in working memory appears to generalize across tasks, offering the potential for remediation in a host of conditions that compromise cognitive function. In particular, computerized training in working memory tasks has shown promise as a rehabilitation strategy after stroke [14], in children with ADHD [27] and intellectual disabilities [28], and in schizophrenic patients [13, 29–31]. Considering the potential impact of working memory training, it is important to understand the neural substrates of changes that occur in the prefrontal cortex. Neurophysiological evidence from nonhuman primates has been particularly revealing in that respect.

3. NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

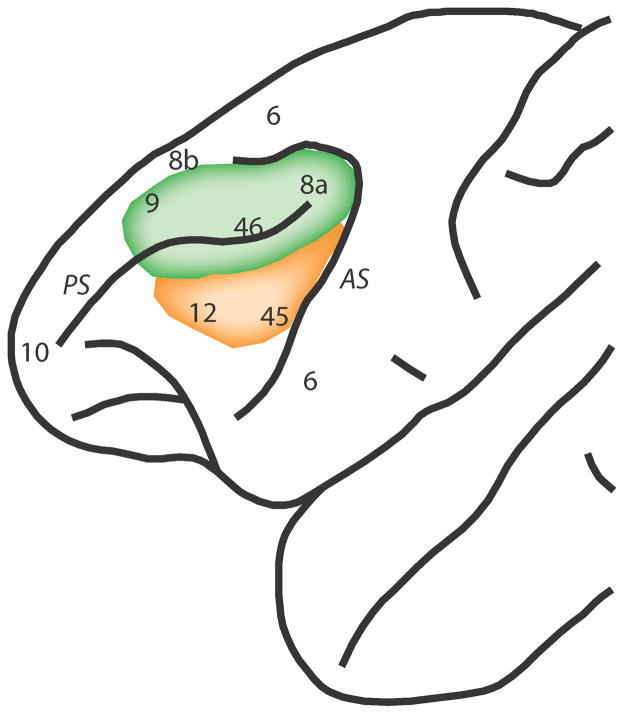

A series of recent studies [12, 32] investigated the effects of training in a working memory task at the level of single neurons, in the lateral prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1). Monkeys were trained to remember two stimuli presented in sequence with intervening delay periods, then decide if the two stimuli were identical in shape and spatial location or not (Fig. 2). Neurophysiological recordings were initially obtained from the monkeys before they had received any training in the task, when the stimuli were presented passively and the monkeys were only required to maintain fixation. A second round of recordings was obtained from the same animals after they were fully trained in task, using the same stimuli, which now were incorporated in the working memory task. Neurons were sampled in an unbiased manner at both rounds of recording, making it possible to determine the nature of neural changes that occur with training. It has been previously known that prefrontal neurons of monkeys only trained to fixate respond to visual stimuli [33]; responses are evident even in anesthetized preparations [34]. The recent experiments examined in depth the properties of neuronal activity in naïve animals and the changes observed after training.

Figure 1.

Lateral view of the monkey brain with the dorsolateral (green) and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (orange) highlighted in relation to anatomical areas. Abbreviations, AS: arcuate sulcus, PS: principal sulcus.

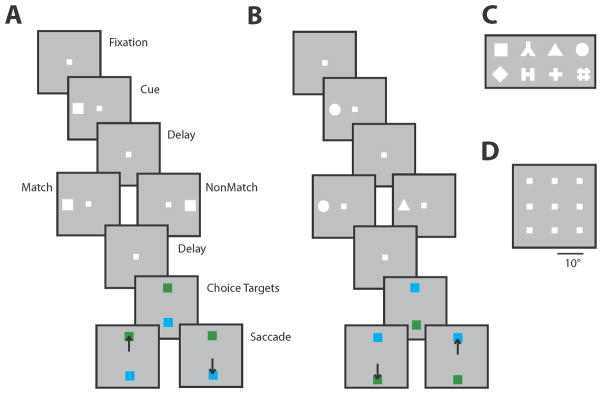

Figure 2.

Behavioral task used to test working memory in monkeys. A. Successive frames illustrate the sequence of presentations on the screen, during the spatial working memory task. Monkeys were required to remember the spatial location of two stimuli presented in sequence and make an eye movement to a green target if the two stimuli matched each other, and the blue target if the did not match. The same stimuli were presented prior to training, without the choice targets. B. Sequence of events in the feature working memory task. C. Set of geometric shapes used in the feature working memory task. D. Set of locations used in the spatial working memory task.

3.1 Properties present prior to training

3.1.1 Persistent Activity

Prefrontal neurons are active in the delay periods of working memory tasks that require animals to remember the properties of transient stimuli [2, 3]. This persistent activity is tuned for the location and shape of the remembered stimulus, thus providing a neural correlate of working memory [35, 36]. This is not an exclusive property of the prefrontal cortex but sustained activity is also present in a network of cortical and subcortical areas [37, 38]. Recent findings demonstrate that persistent activity is not an explicit effect of performing working memory tasks, either. Neurophysiological recordings obtained from naïve animals, required only to fixate revealed that a population of prefrontal neurons continued to be active after the offset of visual stimuli [39].

Persistent discharges in naïve monkeys resembled the responses recorded in animals performing working memory tasks (Fig. 3). Discharges exhibited selectivity for the location and features of the preceding stimulus, indicating that persistent activity represented stimulus properties rather than non-specific factors such as anticipation of the end of the trial or expectation of reward [12, 39]. Approximately 20% of the neurons (22% in the dorsolateral prefrontal and 14% in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex) exhibited significantly elevated activity in the delay period compared to baseline fixation [12]. Activity did not decay shortly after the offset of the stimulus but persisted throughout the entire delay period [39]. When two stimuli were presented in sequence, location-specific persistent activity was also observed after both the first and second stimulus [39]. Information about the identity of a stimulus generally did not survive a second stimulus presentation but successive presentations were followed by persistent activity related to the most recent stimulus. Two types of temporal activation profile were observed, involving either an increase in activity during the delay period or a slight decrease relative to the stimulus presentation, similar to what has been reported during the execution of working memory tasks [4, 40, 41]. Persistent discharges in animals passively viewing stimuli were also observed in the posterior parietal cortex, at least for delay periods lasting for 0.5 s [42]. This activity does not appear to be limited to the simple geometric shapes used as visual stimuli in the aforementioned studies. Anecdotal evidence has been reported for the persistent discharge of facially selective neurons in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex of a monkey trained to only to fixate [43].

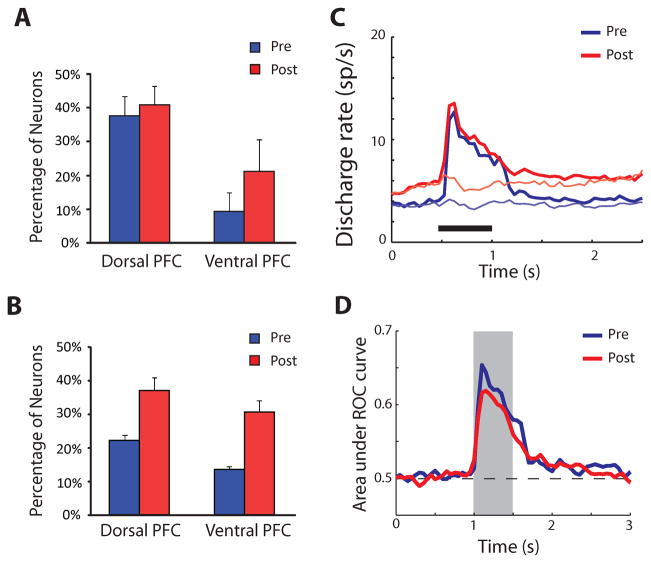

Figure 3.

Summary of changes in neural activity after training to perform a working memory task. A. Percentage of neurons activated by a visual stimulus of the spatial working memory set in the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, before and after training in a working memory task. B. Percentage of neurons active during the delay period. C. Average firing rate of dorsolateral prefrontal neurons to presentation of a stimulus of the spatial set at the best location in the receptive field (thick line) and its diametric location (thin line), before and after training. D. Average ROC value for the discriminability of the best stimulus compared to its diametric one, before and after training. Panels A, B, and D adapted from Qi et al., 2011; Panel C from Meyer et al., 2011.

Working memory is often assumed to be an active process requiring conscious effort [44, 45]. The definition of working memory used widely today emphasizes its dynamic nature and its role in the integration and manipulation of information for the guidance of behavior as opposed to passive storage [46–48]. However the results from naïve monkeys suggest that the neural systems implicated in working memory may also be active during passive presentation of stimuli. Such a definition is consistent with our intuition, as we are able to recall stimuli even when we are not explicitly prompted to remember them. Therefore, activity present during the active maintenance of working memory is generated in an automatic fashion during passive exposure to sensory stimuli which may have no behavioral relevance. Neither training nor effortful execution of a behavioral task are necessary for neural activity. Rather, it seems that even task-irrelevant stimuli presented in a passive manner generate neuronal responses that outlast the physical stimulation and could provide a buffer for working memory available for a number of possible operations.

3.1.2 Match and nonmatch responses

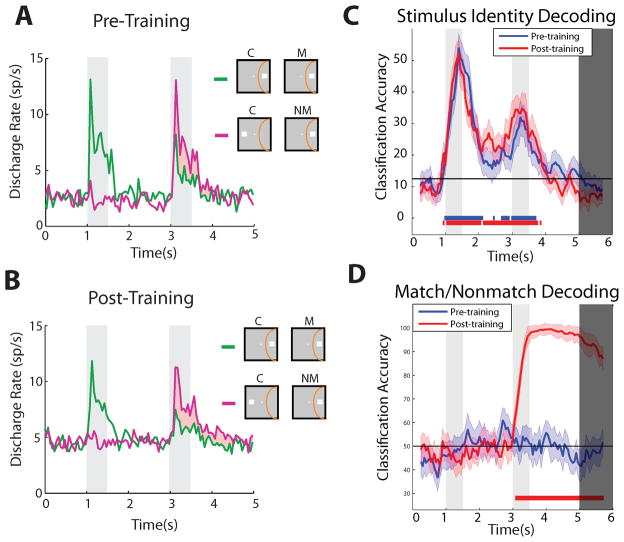

In addition to persistent activity, prefrontal neurons (in trained subjects) exhibit modulation of firing rate in the context of tasks that require comparisons of stimuli or choices between alternatives [49–52]. For example, when subjects are required to compare two stimuli presented in sequence, prefrontal neurons respond differently to the second stimulus depending on its relation to the first [53, 54]. Such modulation of responses can be viewed as a neural correlate of the remembered stimulus, as well as a correlate of the comparison judgment [55]. In fact, the magnitude of response difference to match and nonmatch stimuli differs systematically in correct and error trials, consistent with the idea that this activity guides the subject’s decision [52]. This difference between match and nonmatch responses was observed in monkeys after they were trained in the working memory task of Fig. 2 and made it possible to compare activity in the same animals prior to training [56]. A population of lateral prefrontal neurons was found to signal if two stimuli matched, even before the monkeys were trained to make such a judgment [56]. Approximately 20% of prefrontal neurons responding to visual stimuli exhibited firing rate modulation based on the match or nonmatch stimulus (an overall preference for one of the two or an interaction between spatial preference and match/nonmatch status – Fig. 4). Equal percentages of neurons (50%) had an overall preference for match or nonmatch stimuli, although across the population of neurons, average responses for a match were reduced overall compared to those for a nonmatch. In this case too, it appears that the prefrontal cortex automatically encodes some stimulus relationships even when there is no explicit requirement for comparison, providing relational information that may be drawn upon to guide decision making.

Figure 4.

Responses to matching and non-matching stimuli before and after training. A. Average firing rate from prefrontal neurons with an overall preference for a match stimulus over a nonmatch stimulus, in monkeys naïve to training. Stimuli differed in terms of their spatial location. Shaded area represents the difference in responses for the identical stimulus, when it was presented as match vs. as a nonmatch. Insets represent schematic sequence of stimuli with respect to the receptive field (yellow arc), which differed for each neuron; titles over labels indicate cue (C), match (M) and nonmatch (NM) stimuli. B. Average firing rate from neurons with preference for a spatial match stimulus, after training. C. Classification accuracy achieved by a decoder for different feature stimuli, before and after training. D. Classification accuracy for the matching or non-matching status of feature stimuli, before and after training. Accurate decoding was possible only after training for this stimulus set. Panels A and B adapted from Qi et al., 2012; panels C and D from Meyers et al., 2012.

Activity observed for the repeated presentation of a stimulus in various tasks is typically reduced, a phenomenon termed repetition suppression [57]. It is unclear whether repetition suppression is a result of mechanisms acting at the level of the neurons excited by the stimulus, such as fatigue or sharpening of neuronal responses [58, 59], or an effect of top-down influences [60–62]. The effect observed in naïve animals goes beyond repetition suppression; neurons with preference for the match and neurons with interaction between stimulus location and match/nonmatch status were also observed. If differential activity to match and nonmatch stimuli constitutes a top-down signal to other areas, these results indicate that it is present prior to training that requires judgment or comparison.

3.2 Effects of training on neuronal discharge rate

The influence of training on prefrontal activity has been investigated for several decades. Early experiments addressing the effects of training on delayed response tasks detected increases in electrocorticogram signals from the prefrontal cortex over the time course of training [63, 64]. Subsequent single-neuron recordings using a go/no-go task revealed that more prefrontal neurons are activated in animals that perform the task more accurately, presumably during a more advanced stage of learning, compared to neurons in animals exhibiting poor command of the task [65]. The activity of individual prefrontal neurons can also rapidly increase within the course of a single behavioral session of an associative learning task, when novel stimuli acquire meaning and are associated with a rewarded response [66, 67].

Comparison of neuronal recordings to identical stimuli before and after training revealed a number of changes in neuronal firing related to learning and execution of the task (Fig. 3A–B). After training, a larger number of neurons were activated by the same stimuli [12, 32]. The difference was particularly pronounced in the delay period where approximately 35% of all neurons sampled were active during execution of either the spatial or feature working memory task compared to 20% prior to training (pooled across areas). The percentage of activated neurons doubled for the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, where approximately 40% of neurons were activated after training compared to 20% before (pooled across tasks and task periods). In contrast, only a minor effect of training was observed during the stimulus presentation period in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, where 38% and 41% of neurons were activated before and after training [32]. Importantly, in animals trained only to perform a spatial working memory task, no effect of increased firing rate was observed during the delay period for shape stimuli, which continued to be presented passively [12]. The result suggests that the increased activation was specifically related to the working memory task.

Firing rate increased after training even when limiting comparison among those neurons that were activated by the stimuli. This was most pronounced during the delay period, and in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex [12]. Interestingly, Regular Spiking (putative pyramidal) neurons accounted for most of the increase during the delay period, and Fast Spiking neurons (putative interneurons) exhibited the highest increase during the stimulus presentation period [32].

As was the case with persistent activity in the delay period, the percentage of neurons with significant preference for match and nonmatch stimuli doubled after training (Fig. 4B), increasing from approximately 20% to 40% [56]. An overall preference for nonmatch over match stimuli (match suppression) was also apparent after training [56]. On the other hand, no significant differences were observed for activity that could mediate other comparisons about the stimuli that the monkeys were not explicitly trained for, e.g. the percentage of neurons representing simultaneously the location of the first and second stimulus [56].

Despite the increased activation, the average selectivity of individual neurons for stimuli declined after training (Fig. 3D). This was an unexpected finding considering that the animals were specifically trained to recognize and discriminate between these stimuli [12, 32]. Compared with being trained to perform a fine discrimination between stimuli, this is a very different training effect; an increase in stimulus selectivity has been observed in the prefrontal cortex after perceptual training involving recognition of degraded objects [68]. The decrease in selectivity after task training was apparent when considering the percentage of neurons with significant selectivity for spatial or shape stimuli [12] and the average discriminability for different stimuli among all neurons [32]. The decrease was mostly attributed to Regular Spiking (putative pyramidal) neurons. Examining the quality of spatial information specifically during the delay period also revealed a relative decrease in selectivity. Although the delay period activity increased considerably (e.g. from an average of 5.4 spikes/s prior to training to 8.5 spikes/s after training among all dorsolateral neurons with visual responses), the percentage of neurons with significant selectivity for the stimuli declined equally appreciably, from 37% to 27% [12]. A likely explanation of this phenomenon is that neuronal activity after training represents factors non-specific to the stimuli, related to the rules and execution of the task so that selectivity to stimuli themselves declined as a percentage of total neuronal activity [32].

3.3 Effects of training on discharge variability and correlation between neurons

In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that cognitive factors such as attention and working memory do not affect only the mean firing rate of neurons, but the variability of discharge rates and the correlation between neuronal discharges, as well [69–73]. Therefore it is interesting to consider the effects of task learning on discharge variability and correlation.

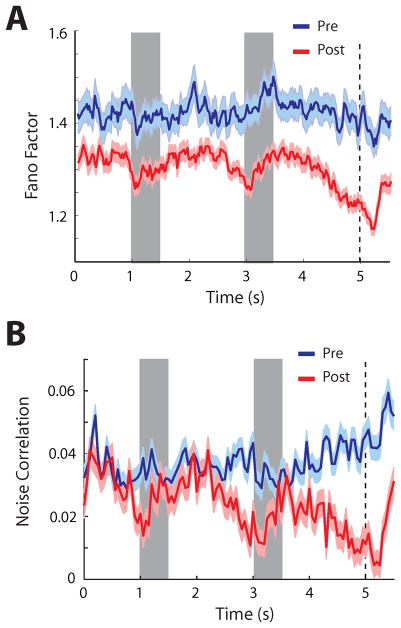

Analysis of prefrontal recordings obtained before and after training revealed an overall decrease in both discharge variability and trial-to-trial correlation (noise correlation) between neurons [74, 75]. Discharge variability, as quantified by the Fano Factor (variance over mean of neuronal responses – Fig. 5A), exhibited an overall decrease of approximately 7.5% after training [74]. This was comparable to effects of attention previously described in the context of behavioral tasks [70, 76]. The decrease after training was apparent not only during the stimulus presentation period but during the baseline fixation period as well [74]. At the same time, the Fano Factor decreased during the stimulus presentation relative to the baseline fixation period both before and after training, suggesting that the reduction in discharge variability after training interacts in an additive way with the effect of the stimulus presentation. After training, changes in neuronal variability depended on the properties of neurons analyzed. The largest decrease was observed for the group of neurons that responded to stimuli after training compared to equivalent neurons, prior to training [74].

Figure 5.

Changes in discharge variability and correlation after training. A. Average Fano Factor, a measure of firing rate variability, is plotted as a function of time across all neurons and stimulus presentations, before and after training. B. Average noise correlation in the firing rate of pairs of neurons recorded simultaneously from separate electrodes, plotted as a function of time. Panel A, from Qi and Constantinidis 2012a; panel B from Qi and Constantinidis, 2012b.

Changes in correlations between prefrontal neurons after training mirrored changes in neuronal discharge variability (Fig. 5B). Noise correlation, the trial-to-trial correlation of neuronal discharges around their respective means (also known as spike-count correlation) demonstrated an approximately 50% overall decrease after training [75]. The changes in noise correlation were also not uniform but varied across task epochs and neuronal populations. The greatest decrease was observed for pairs of neurons with most similar tuning for stimulus properties and for pairs of Fast Spiking – Regular Spiking neurons compared with Regular Spiking – Regular Spiking (putative pyramidal) neurons.

Collectively, the effects of reduced variability and correlation suggest improved representation of stimulus properties in the population of prefrontal neurons after training. A paradoxical effect of training was reduced selectivity for stimuli at the level of single neuron firing rate. Decreased variability can improve the efficiency of neural coding by increasing the information encoded in neuronal firing [77]. In fact, despite the decrease in average stimulus selectivity it was possible to decode shape information (Fig. 4C) as well as spatial information [78] with equivalent accuracy before and after training. Similarly, reduced correlation can increase the information that can be extracted by pooling activity from multiple neurons [79]. Stimulus representation is therefore improved across the population of neurons in conditions when variability and correlation decrease [76], and these changes counteract the effects of decreased stimulus selectivity.

3.4 Properties of ventral and dorsal prefrontal cortex

The organization of the prefrontal cortex with respect to the representation of different stimuli and cognitive functions remains a matter of debate. Anatomical evidence suggests a relative segregation of projections from the posterior parietal cortex, which terminate mostly to the dorsalprefrontal cortex (areas 8 and 46), and from the inferior temporal cortex, which terminate on areas 12 and 45 of the ventral prefrontal cortex [38, 80–83]. By some physiological accounts, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex represents primarily spatial information whereas the ventrolateral aspect is specialized for object identity information [84, 85]. The domain-specific organization can be thought of as an extension of the dorsal and ventral visual streams [86, 87]. On the other hand, other physiological studies have reported the existence of prefrontal neurons selective for both types of information throughout the prefrontal cortex, particularly after monkeys have been trained in tasks that required them to remember both the location and identity of a stimulus [88, 89]. The implication is that functional specialization observed in some studies is the result of task requirements [88, 89]. This integrative model suggests a plastic prefrontal organization that is shaped by cognitive demands imposed by the task. Strong evidence exists that prior experience is capable of shaping neuronal preferences across the cortical surface; areas as early as the primary sensory cortex have been shown to reorganize after training [90–92]. Human imaging studies have also been equivocal about the functional organization of the prefrontal cortex, with some studies lending support to the idea that specialized processing occurs within the two prefrontal subdivisions [93–96], whereas other favour an organization in terms of cognitive operations rather than type of information [97–99]. Recordings from the lateral prefrontal cortex before and after training in working memory tasks provided the opportunity to examine directly the innate organization of the prefrontal cortex with regards to stimulus selectivity and the effects of training to perform spatial, non-spatial, and integrative working memory tasks [12].

Prior to training, neurons in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex exhibited a higher percentage of neurons selective for spatial location and a higher magnitude of spatial selectivity. Conversely, a higher magnitude of selectivity for shapes of stimuli was observed in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, supporting a domain-specific organization [12]. Ventrolateral prefrontal neurons were also less likely to be driven by any stimulus (among the set of geometric shapes used in these experiments), consistent with a higher specialization for stimulus features such as that reported for inferior temporal neurons [100–103]. After monkeys were trained to perform working memory tasks, dorsolateral prefrontal neurons maintained their advantage in terms of spatial selectivity [12]. A larger percentage of dorsolateral than ventrolateral prefrontal neurons exhibited significant selectivity for spatial stimuli, and with a higher magnitude of selectivity, consistent with a specialization of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for spatial information. It is worth noting that these experiments were conducted in the posterior half of the lateral prefrontal cortex and it is possible that more abstract information and task processes are represented in the anterior half of the prefrontal cortex [104]. The decrease in overall stimulus selectivity mentioned earlier was mostly localized in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, also resulting in a decrease in the percentage of neurons with combined selectivity for both spatial and shape information [12]. Within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, it was possible to further distinguish the effects of training between the principle sulcus region and the superior-lateral prefrontal cortex. The increase in firing rate among dorsal prefrontal neurons was localized in the zone around the principal sulcus. This result is consistent with lesion studies suggesting that the principal sulcus region in particular is critical for maintenance in memory of task-related information whereas lesions of the superior lateral prefrontal cortex produce essentially no deficit in that respect [105]. Dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal neurons also differed in the percentage of neurons differentiating between match and non match spatial stimuli with twice as many dorsolateral prefrontal neurons exhibiting such preference [56].

3.5 Incorporation of new information

The preceding sections of this review illustrated that many properties of prefrontal neurons that were previously observed in trained animals, such as persistent activity, selectivity for match and nonmatch stimuli, and dorsolateral and ventrolateral specialization, were in fact present prior to any training. This leaves the question open of how information about new tasks is incorporated in neuronal activity. This was addressed by examining the responses to different shapes before and after training, and quantifying the information that could be decoded using a classifier [78]. Information about the matching status of shape stimuli was essentially absent prior to training (although information about the shape itself could be reliably decoded with the classifier – Fig. 4C,D). After training, robust information about the match/nonmatch status of the shape stimuli could be decoded from the prefrontal cortex [78]. This information was encoded in a dynamic population code, with different neurons carrying information at different time intervals during the trial, consistent with recent reports of dynamic coding in the prefrontal cortex [106–108], and other cortical areas [109]. On the single neuron level, a small population of neurons highly selective for the match/nonmatch status of shape stimuli contained almost all the task-relevant information that was present after training [78]. At the same time, a larger population of neurons exhibited task relevant informationto a lesser degree. Furthermore, information about the task was present in the same neurons that were selective for shape information, often manifesting itself in relatively short time windows, in the midst of other large firing rate modulations that occurred throughout the trial. In essence, prefrontal neurons multiplexed different types of information, some of which were present prior to training and some that only appeared after training in the task [78].

4. DISCUSSION

The prefrontal cortex is activated in a wide range of cognitive functions. Recent neurophysiological studies in non-human primates have revealed neural correlates of attention, rules, decisions, categories, numerical quantities, conflicting choices, and sequences of actions [7, 10, 49, 50, 110–115] in prefrontal activity. Responses of prefrontal neurons clearly depend on the task a subject has been trained to perform [5–7], suggesting that patterns of prefrontal activation observed in the context of these tasks is likely to be influenced by the demands of the task themselves. The evidence reviewed in this article examined the properties of prefrontal neurons in naïve monkeys and how they were influenced after training in a task. Individual neurons exhibit at least some neural correlates of cognitive functions prior to any training and some of the changes induced by training and executing a working memory task appear to be quantitative rather than qualitative. Additionally, the lateral prefrontal cortex appears to be subdivided in a dorsolateral and ventrolateral aspect whose properties remain distinct before and after training. On the other hand, undeniably novel information is also reflected in the activity of prefrontal neurons after training. This appears to be achieved through the emergence of a small population of neurons that are highly specialized for the new information, while continuing to represent information about stimulus attributes that were present before training.

The neurophysiological results demonstrated an overall increase in prefrontal activity after initial training in tasks that required working memory. This result parallels the increased activation observed in some human studies after training in working memory tasks [11, 15–18]. The increase was observed even though the monkey working memory training did not involve increased capacity or duration over ~3 seconds and did not otherwise parallel the complexity of tasks used in the human literature. The result suggests that the initial learning of a working memory task already requires increased prefrontal activation, learning which is typically achieved in human studies very quickly. Additional activation might be expected if the monkeys were subsequently trained with tasks specifically designed to increase the duration or capacity of working memory.

Relatively little is known yet about the time scale of the changes discussed in this article. Individual neurons can alter their response properties when required to learn or alternate between rules of a task in the time scale of a behavioral session lasting less than an hour [6, 66]. Learning to perform the task itself requires training sessions spanning several months and it is unclear whether changes are incremental or abrupt, following acquisition of specific elements. It is also unknown what the effect of training are at the single neuron level during training increasing the capacity and duration of working memory, which have revealed increased activation in fMRI studies. These are questions that will need to be addressed by future studies. Understanding the nature of changes that characterize learning will be valuable in devising more effective programs of cognitive training in human populations as well.

Research Highlights.

Prior to training, prefrontal neurons exhibit persistent activity

After training more neurons are recruited by visual stimuli at higher firing rates

The variability of discharges and correlation between neurons decrease

New information is incorporated in the activity of a small population of neurons

Selectivity of dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex remain unchanged

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 EY017077, and by the Tab Williams Family Endowment Fund. We wish to thank Anthony Elworthy for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster JM, Alexander GE. Neuron activity related to short-term memory. Science. 1971;173:652–4. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3997.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funahashi S, Bruce CJ, Goldman-Rakic PS. Mnemonic coding of visual space in the monkey’s dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:331–49. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Constantinidis C, Franowicz MN, Goldman-Rakic PS. The sensory nature of mnemonic representation in the primate prefrontal cortex. Nature Neurosci. 2001;4:311–6. doi: 10.1038/85179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White IM, Wise SP. Rule-dependent neuronal activity in the prefrontal cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1999;126:315–35. doi: 10.1007/s002210050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asaad WF, Rainer G, Miller EK. Task-specific neural activity in the primate prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:451–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallis JD, Anderson KC, Miller EK. Single neurons in prefrontal cortex encode abstract rules. Nature. 2001;411:953–6. doi: 10.1038/35082081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshi E, Shima K, Tanji J. Task-dependent selectivity of movement-related neuronal activity in the primate prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:3392–7. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shima K, Isoda M, Mushiake H, Tanji J. Categorization of behavioural sequences in the prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2007;445:315–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman DJ, Riesenhuber M, Poggio T, Miller EK. Categorical representation of visual stimuli in the primate prefrontal cortex. Science. 2001;291:312–6. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olesen PJ, Westerberg H, Klingberg T. Increased prefrontal and parietal activity after training of working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:75–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer T, Qi XL, Stanford TR, Constantinidis C. Stimulus selectivity in dorsal and ventral prefrontal cortex after training in working memory tasks. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6266–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6798-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramaniam K, Luks TL, Fisher M, Simpson GV, Nagarajan S, Vinogradov S. Computerized cognitive training restores neural activity within the reality monitoring network in schizophrenia. Neuron. 2012;73:842–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westerberg H, Jacobaeus H, Hirvikoski T, Clevberger P, Ostensson ML, Bartfai A, et al. Computerized working memory training after stroke--a pilot study. Brain Inj. 2007;21:21–9. doi: 10.1080/02699050601148726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNab F, Varrone A, Farde L, Jucaite A, Bystritsky P, Forssberg H, et al. Changes in cortical dopamine D1 receptor binding associated with cognitive training. Science. 2009;323:800–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1166102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hempel A, Giesel FL, Garcia Caraballo NM, Amann M, Meyer H, Wustenberg T, et al. Plasticity of cortical activation related to working memory during training. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:745–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahlin E, Neely AS, Larsson A, Backman L, Nyberg L. Transfer of learning after updating training mediated by the striatum. Science. 2008;320:1510–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1155466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore CD, Cohen MX, Ranganath C. Neural mechanisms of expert skills in visual working memory. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11187–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1873-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fletcher P, Buchel C, Josephs O, Friston K, Dolan R. Learning-related neuronal responses in prefrontal cortex studied with functional neuroimaging. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:168–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyberg L, Sandblom J, Jones S, Neely AS, Petersson KM, Ingvar M, et al. Neural correlates of training-related memory improvement in adulthood and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13728–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735487100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garavan H, Kelley D, Rosen A, Rao SM, Stein EA. Practice-related functional activation changes in a working memory task. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;51:54–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001001)51:1<54::AID-JEMT6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milham MP, Banich MT, Claus ED, Cohen NJ. Practice-related effects demonstrate complementary roles of anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortices in attentional control. Neuroimage. 2003;18:483–93. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landau SM, Schumacher EH, Garavan H, Druzgal TJ, D’Esposito M. A functional MRI study of the influence of practice on component processes of working memory. Neuroimage. 2004;22:211–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansma JM, Ramsey NF, Slagter HA, Kahn RS. Functional anatomical correlates of controlled and automatic processing. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;13:730–43. doi: 10.1162/08989290152541403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayala S, Sala JB, Courtney SM. Increased neural efficiency with repeated performance of a working memory task is information-type dependent. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:609–17. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klingberg T. Training and plasticity of working memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klingberg T, Forssberg H, Westerberg H. Training of working memory in children with ADHD. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24:781–91. doi: 10.1076/jcen.24.6.781.8395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soderqvist S, Nutley SB, Ottersen J, Grill KM, Klingberg T. Computerized training of non-verbal reasoning and working memory in children with intellectual disability. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2012;6:271. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wexler BE, Anderson M, Fulbright RK, Gore JC. Preliminary evidence of improved verbal working memory performance and normalization of task-related frontal lobe activation in schizophrenia following cognitive exercises. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1694–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popov T, Jordanov T, Rockstroh B, Elbert T, Merzenich MM, Miller GA. Specific cognitive training normalizes auditory sensory gating in schizophrenia: a randomized trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:465–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haut KM, Lim KO, MacDonald A., 3rd Prefrontal cortical changes following cognitive training in patients with chronic schizophrenia: effects of practice, generalization, and specificity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1850–9. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi XL, Meyer T, Stanford TR, Constantinidis C. Changes in Prefrontal Neuronal Activity after Learning to Perform a Spatial Working Memory Task. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2722–32. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki H, Azuma M. Topographic studies on visual neurons in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1983;53:47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00239397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmolesky MT, Wang Y, Hanes DP, Thompson KG, Leutgeb S, Schall JD, et al. Signal timing across the macaque visual system. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3272–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldman-Rakic PS. Cellular basis of working memory. Neuron. 1995;14:477–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Constantinidis C, Wang XJ. A neural circuit basis for spatial working memory. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:553–65. doi: 10.1177/1073858404268742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldman-Rakic PS. Topography of cognition: parallel distributed networks in primate association cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:137–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constantinidis C, Procyk E. The primate working memory networks. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4:444–65. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer T, Qi XL, Constantinidis C. Persistent discharges in the prefrontal cortex of monkeys naive to working memory tasks. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17 (Suppl 1):i70–6. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quintana J, Fuster JM. Mnemonic and predictive functions of cortical neurons in a memory task. Neuroreport. 1992;3:721–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qi XL, Katsuki F, Meyer T, Rawley JB, Zhou X, Douglas KL, et al. Comparison of neural activity related to working memory in primate dorsolateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortex. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:12. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joelving FC, Compte A, Constantinidis C. Temporal properties of posterior parietal neuron discharges during working memory and passive viewing. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2254–66. doi: 10.1152/jn.00977.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scalaidhe SP, Wilson FA, Goldman-Rakic PS. Face-selective neurons during passive viewing and working memory performance of rhesus monkeys: evidence for intrinsic specialization of neuronal coding. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:459–75. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frith C, Dolan R. The role of the prefrontal cortex in higher cognitive functions. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 1996;5:175–81. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(96)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Postle BR. Working memory as an emergent property of the mind and brain. Neuroscience. 2006;139:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith EE, Kosslyn SM. Cognitive Psychology: mind and brain. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baddeley A. Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:829–39. doi: 10.1038/nrn1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Funahashi S. Prefrontal cortex and working memory processes. Neuroscience. 2006;139:251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JN, Shadlen MN. Neural correlates of a decision in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the macaque. Nature Neurosci. 1999;2:176–85. doi: 10.1038/5739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barraclough DJ, Conroy ML, Lee D. Prefrontal cortex and decision making in a mixed-strategy game. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:404–10. doi: 10.1038/nn1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumoto K, Suzuki W, Tanaka K. Neuronal correlates of goal-based motor selection in the prefrontal cortex. Science. 2003;301:229–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1084204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaksas D, Pasternak T. Directional signals in the prefrontal cortex and in area MT during a working memory for visual motion task. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11726–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3420-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romo R, Brody CD, Hernandez A, Lemus L. Neuronal correlates of parametric working memory in the prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1999;399:470–3. doi: 10.1038/20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romo R, Salinas E. Flutter discrimination: neural codes, perception, memory and decision making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:203–18. doi: 10.1038/nrn1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Constantinidis C. Posterior parietal mechanisms of visual attention. Rev Neurosci. 2006;17:415–27. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qi XL, Meyer T, Stanford TR, Constantinidis C. Neural correlates of a decision variable before learning to perform a Match/Nonmatch task. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6161–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6365-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grill-Spector K, Henson R, Martin A. Repetition and the brain: neural models of stimulus-specific effects. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaliukhovich DA, Vogels R. Stimulus repetition probability does not affect repetition suppression in macaque inferior temporal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1547–58. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grill-Spector K, Malach R. fMR-adaptation: a tool for studying the functional properties of human cortical neurons. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2001;107:293–321. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(01)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friston K. A theory of cortical responses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:815–36. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Summerfield C, Trittschuh EH, Monti JM, Mesulam MM, Egner T. Neural repetition suppression reflects fulfilled perceptual expectations. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1004–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Engel TA, Wang XJ. Same or different? A neural circuit mechanism of similarity-based pattern match decision making. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6982–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6150-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stamm JS, Gadotti A, Rosen SC. Interhemispheric functional differences in prefrontal cortex of monkeys. J Neurobiol. 1975;6:39–49. doi: 10.1002/neu.480060108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stamm JS, Rosen SC. Electrical stimulation and steady potential shifts in prefrontal cortex during delayed response performance by monkeys. Acta Biol Exp (Warsz) 1969;29:385–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kubota K, Komatsu H. Neuron activities of monkey prefrontal cortex during the learning of visual discrimination tasks with GO/NO-GO performances. Neurosci Res. 1985;3:106–29. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(85)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asaad WF, Rainer G, Miller EK. Neural activity in the primate prefrontal cortex during associative learning. Neuron. 1998;21:1399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puig MV, Miller EK. The role of prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors in the neural mechanisms of associative learning. Neuron. 2012;74:874–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rainer G, Miller EK. Effects of visual experience on the representation of objects in the prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2000;27:179–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell JF, Sundberg KA, Reynolds JH. Differential attention-dependent response modulation across cell classes in macaque visual area V4. Neuron. 2007;55:131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Churchland MM, Yu BM, Cunningham JP, Sugrue LP, Cohen MR, Corrado GS, et al. Stimulus onset quenches neural variability: a widespread cortical phenomenon. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:369–78. doi: 10.1038/nn.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Churchland AK, Kiani R, Chaudhuri R, Wang XJ, Pouget A, Shadlen MN. Variance as a signature of neural computations during decision making. Neuron. 2011;69:818–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohen MR, Newsome WT. Context-dependent changes in functional circuitry in visual area MT. Neuron. 2008;60:162–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen MR, Newsome WT. Estimates of the contribution of single neurons to perception depend on timescale and noise correlation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6635–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5179-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qi XL, Constantinidis C. Variability of prefrontal neuronal discharges before and after training in a working memory task. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qi XL, Constantinidis C. Correlated discharges in the primate prefrontal cortex before and after working memory training. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:3538–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cohen MR, Maunsell JH. Attention improves performance primarily by reducing interneuronal correlations. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1594–600. doi: 10.1038/nn.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oram MW. Visual stimulation decorrelates neuronal activity. J Neurophysiol. 2010;105:942–57. doi: 10.1152/jn.00711.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meyers EM, Qi XL, Constantinidis C. Incorporation of new information into prefrontal cortical activity after learning working memory tasks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4651–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201022109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zohary E, Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Correlated neuronal discharge rate and its implications for psychophysical performance. Nature. 1994;370:140–3. doi: 10.1038/370140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Common cortical and subcortical targets of the dorsolateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices in the rhesus monkey: evidence for a distributed neural network subserving spatially guided behavior. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4049–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04049.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cavada C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Posterior parietal cortex in rhesus monkey: II. Evidence for segregated corticocortical networks linking sensory and limbic areas with the frontal lobe. J Comp Neurol. 1989;287:422–45. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Petrides M, Pandya DN. Projections to the frontal cortex from the posterior parietal region in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1984;228:105–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.902280110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Romanski LM, Tian B, Fritz J, Mishkin M, Goldman-Rakic PS, Rauschecker JP. Dual streams of auditory afferents target multiple domains in the primate prefrontal cortex. Nature Neurosci. 1999;2:1131–6. doi: 10.1038/16056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O’Scalaidhe S, Wilson FA, Goldman-Rakic PS. Areal segregation of face-processing neurons in prefrontal cortex. Science. 1997;278:1135–8. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilson FA, Scalaidhe SP, Goldman-Rakic PS. Dissociation of object and spatial processing domains in primate prefrontal cortex. Science. 1993;260:1955–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8316836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ungerleider LG, Mishkin M. Two cortical visual systems. In: Ingle DJ, Goodale MA, Mansfield RJW, editors. Analysis of Visual Behavior. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1982. pp. 549–86. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:1–47. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rao SC, Rainer G, Miller EK. Integration of what and where in the primate prefrontal cortex. Science. 1997;276:821–4. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rainer G, Asaad WF, Miller EK. Memory fields of neurons in the primate prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15008–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory cortex following discrimination training in adult owl monkeys. J Neurosci. 1993;13:87–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00087.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Recanzone GH, Merzenich MM, Jenkins WM, Grajski KA, Dinse HR. Topographic reorganization of the hand representation in cortical area 3b owl monkeys trained in a frequency-discrimination task. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1031–56. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li W, Piech V, Gilbert CD. Perceptual learning and top-down influences in primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:651–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adcock RA, Constable RT, Gore JC, Goldman-Rakic PS. Functional neuroanatomy of executive processes involved in dual-task performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060588897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leung HC, Gore JC, Goldman-Rakic PS. Sustained mnemonic response in the human middle frontal gyrus during on-line storage of spatial memoranda. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:659–71. doi: 10.1162/08989290260045882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sala JB, Courtney SM. Binding of what and where during working memory maintenance. Cortex. 2007;43:5–21. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Volle E, Kinkingnehun S, Pochon JB, Mondon K, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Seassau M, et al. The functional architecture of the left posterior and lateral prefrontal cortex in humans. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2460–9. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Owen AM, Stern CE, Look RB, Tracey I, Rosen BR, Petrides M. Functional organization of spatial and nonspatial working memory processing within the human lateral frontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7721–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Owen AM, Doyon J, Petrides M, Evans AC. Planning and spatial working memory: a positron emission tomography study in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:353–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stern CE, Owen AM, Tracey I, Look RB, Rosen BR, Petrides M. Activity in ventrolateral and mid-dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during nonspatial visual working memory processing: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2000;11:392–9. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gross CG, Rocha-Miranda CE, Bender DB. Visual properties of neurons in inferotemporal cortex of the Macaque. J Neurophysiol. 1972;35:96–111. doi: 10.1152/jn.1972.35.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Desimone R, Albright TD, Gross CG, Bruce C. Stimulus-selective properties of inferior temporal neurons in the macaque. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2051–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-08-02051.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tanaka K, Saito H, Fukada Y, Moriya M. Coding visual images of objects in the inferotemporal cortex of the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:170–89. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fujita I, Tanaka K, Ito M, Cheng K. Columns for visual features of objects in monkey inferotemporal cortex. Nature. 1992;360:343–6. doi: 10.1038/360343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Badre D, D’Esposito M. Is the rostro-caudal axis of the frontal lobe hierarchical? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:659–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Buckley MJ, Mansouri FA, Hoda H, Mahboubi M, Browning PG, Kwok SC, et al. Dissociable components of rule-guided behavior depend on distinct medial and prefrontal regions. Science. 2009;325:52–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1172377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Machens CK, Romo R, Brody CD. Functional, But Not Anatomical, Separation of “What” and “When” in Prefrontal Cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:350–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3276-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Warden MR, Miller EK. The representation of multiple objects in prefrontal neuronal delay activity. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17 (Suppl 1):i41–50. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meyers EM, Freedman DJ, Kreiman G, Miller EK, Poggio T. Dynamic population coding of category information in inferior temporal and prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1407–19. doi: 10.1152/jn.90248.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Crowe DA, Averbeck BB, Chafee MV. Rapid sequences of population activity patterns dynamically encode task-critical spatial information in parietal cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11640–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0954-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nieder A, Freedman DJ, Miller EK. Representation of the quantity of visual items in the primate prefrontal cortex. Science. 2002;297:1708–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1072493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Averbeck BB, Chafee MV, Crowe DA, Georgopoulos AP. Parallel processing of serial movements in prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13172–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162485599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mansouri FA, Buckley MJ, Tanaka K. Mnemonic function of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in conflict-induced behavioral adjustment. Science. 2007;318:987–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1146384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sigala N, Kusunoki M, Nimmo-Smith I, Gaffan D, Duncan J. Hierarchical coding for sequential task events in the monkey prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11969–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802569105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Katsuki F, Constantinidis C. Early involvement of prefrontal cortex in visual bottom-up attention. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1160–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rainer G, Asaad WF, Miller EK. Selective representation of relevant information by neurons in the primate prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1998;393:577–9. doi: 10.1038/31235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]