Abstract

We sought novel strategies to reduce levels of the polyglutamine androgen receptor (polyQ AR) and achieve therapeutic benefits in models of spinobulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), a protein aggregation neurodegenerative disorder. Proteostasis of the polyQ AR is controlled by the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery, but mechanisms regulating the protein’s turnover are incompletely understood. We demonstrate that overexpression of Hip, a co-chaperone that enhances binding of Hsp70 to its substrates, promotes client protein ubiquitination and polyQ AR clearance. Furthermore, we identify a small molecule that acts similarly to Hip by allosterically promoting Hsp70 binding to unfolded substrates. Like Hip, this synthetic co-chaperone enhances client protein ubiquitination and polyQ AR degradation. Both genetic and pharmacologic approaches targeting Hsp70 alleviate toxicity in a Drosophila model of SBMA. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of allosteric regulators of Hsp70, and provide new insights into the role of the chaperone machinery in protein quality control.

INTRODUCTION

The CAG/polyglutamine disorders are a family of nine neurodegenerative diseases caused by similar microsatellite expansions in coding regions of unrelated genes 1. These disorders are currently untreatable, with symptom onset typically in midlife and death 15 to 20 years later. Among these diseases is spinobulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), a progressive neuromuscular disorder that affects only men and is characterized by proximal limb and bulbar muscle weakness, atrophy and fasciculations 2. The clinical features of SBMA correlate with a loss of lower motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, and with marked myopathic and neurogenic changes in skeletal muscle 2,3. The causative mutation in SBMA is an expansion of a CAG repeat in the first exon of the androgen receptor (AR) gene. The expanded glutamine tract promotes hormone-dependent AR unfolding and oligomerization, steps that are critical to toxicity. In SBMA, as in other CAG/polyglutamine disorders, the mutant protein disrupts multiple downstream pathways, and toxicity likely results from the cumulative effects of altering a diverse array of cellular processes including transcription, RNA splicing, axonal transport and mitochondrial function 4–9. The existence of divergent mechanisms of toxicity suggests that potential treatments targeting a single downstream pathway are likely to be incomplete and unsuccessful.

These observations prompted us to focus instead on understanding the proximal mechanisms that regulate degradation of the polyQ AR, with the goal of harnessing these pathways to diminish levels of the toxic protein and ameliorate the disease phenotype. The cellular machinery that plays the dominant role in regulating proteostasis of the AR is the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery, in which heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), Hsp70 and their co-chaperones function together as a multiprotein complex 10,11. In contrast to the classic model of free chaperones such as Hsp70 interacting with unfolded proteins to facilitate their refolding, the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery instead acts on prefolded proteins in their native or near native conformations to assist in the opening and stabilization of ligand binding clefts, an action that may form a basis for the role of the chaperone machinery in the triage of damaged proteins for degradation 11,12. Access of ligand to the steroid binding clefts of nuclear receptors, including the AR, is dependent upon the Hsp90/Hsp70 chaperone machinery 10,12. Furthermore, as a client of the chaperone machinery, the polyQ AR is stabilized by its interaction with Hsp90.

Key insights into the mechanism by which the chaperone machinery regulates the triage of damaged or unfolded proteins have come from experiments performed using chemical inhibitors of Hsp90. In SBMA models, when Hsp90 is chemically inhibited, the polyQ AR no longer associates with Hsp90 and is rapidly degraded 13,14. Through this mechanism, Hsp90 inhibitors ameliorate the phenotype of SBMA transgenic mice 14,15. However, these Hsp90 inhibitors concurrently induce a stress response. Although this response can be experimentally dissociated from effects on protein triage 13, it nonetheless complicates studies on potential therapeutic benefits. Thus, the chaperone machinery plays a central role in the triage of unfolded proteins, yet the mechanism by which this is accomplished is incompletely understood.

Genetic evidence indicates that Hsp70 plays a central role in promoting clearance of the polyQ AR. Overexpression of Hsp70 or its co-chaperone Hsp40, promotes polyQ AR degradation and diminishes toxicity in cellular models of SBMA 16,17. Similarly, transgenic overexpression of Hsp70 18 or the Hsp70-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP (C-terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein) 19 rescues the phenotype of SBMA mice. While providing a strong rationale for targeting Hsp70, these genetic studies have not yet revealed how this chaperone should be pharmacologically manipulated to favor polyQ AR degradation.

What activity of Hsp70 dictates whether bound substrates will be degraded? Here, we explored the relationship between Hsp70’s nucleotide binding status and its effects on polyQ AR stability. Our strategy is based, in part, on the observation that overexpression of Hip (Hsp70 interacting protein) prevents the accumulation of polyglutamine inclusions in a cellular model 20. Hip is an Hsp70 co-chaperone that stabilizes this ATP hydrolyzing chaperone in its ADP-bound conformation 21,22. The ADP-bound state of Hsp70 has tight affinity for its substrates and a greatly reduced off-rate compared to the ATP-bound conformation 23. Although it was suggested that Hip might act by promoting the Hsp70 refolding cycle, we demonstrate that Hip facilitates the CHIP-mediated ubiquitination of a model Hsp90 client protein and promotes proteasomal degradation of the polyQ AR. These studies suggested that favoring the Hsp70-substrate complex promotes degradation of unfolded or damaged proteins. To further evaluate this model, we identified a small molecule that promotes tight binding of Hsp70 to substrates in vitro. Like Hip, this compound facilitates the ubiquitination and degradation of polyQ AR. Furthermore, we show that both Hip over-expression and the synthetic co-chaperone alleviate toxicity in a Drosophila model of SBMA. Our findings suggest that allosterically favoring the formation of the Hsp70-substrate complex ameliorates the phenotype in models of this protein aggregation neurodegenerative disorder. Moreover, these results provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of protein triage during chaperone-mediated quality control.

RESULTS

Hip promotes ubiquitination and degradation of clients

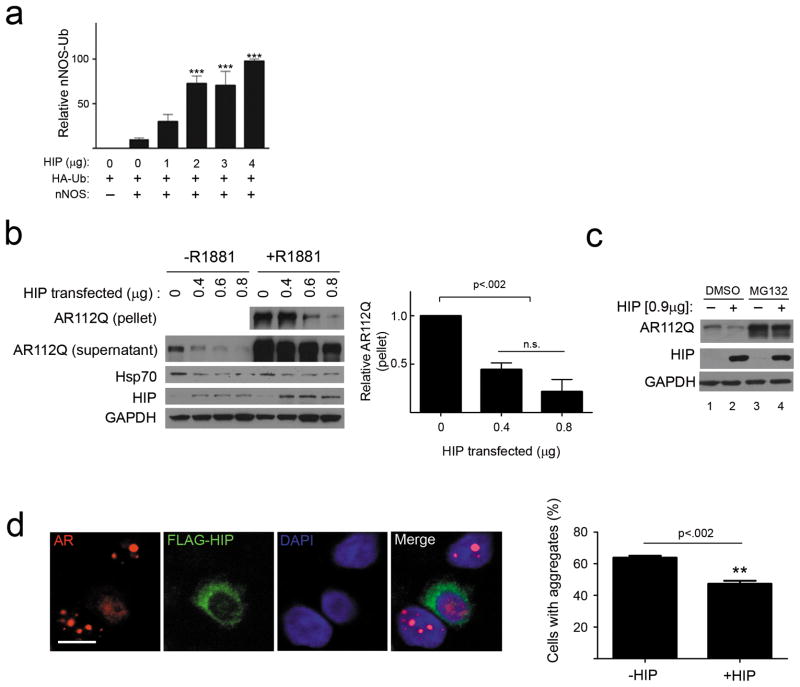

The co-chaperone Hip is known to stabilize Hsp70 in its ADP-dependent conformation 21. As ADP-bound Hsp70 recognizes denatured or damaged substrates with high affinity 22, we hypothesized that Hip overexpression would facilitate Hsp70-dependent ubiquitination and client protein degradation. To test this notion, we first studied a well-characterized Hsp90 client protein, neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). nNOS ubiquitination is dependent upon Hsp70 24 and is mediated by CHIP 24–26. Using an established system to study nNOS ubiquitination 27, we found that Hip overexpression yielded a significant, dose-dependent increase in the accumulation of ubiquitinated nNOS species in cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin (Fig. 1a, and Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig 1). This observation suggested that a similar strategy could also promote clearance of toxic proteins that are clients of the Hsp90/Hsp70 chaperone machinery. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed Hip with the polyQ AR, an Hsp90 client that causes neuromuscular toxicity in SBMA. In this model, unfolding and aggregation of AR containing 112 glutamines (AR112Q) is dependent upon the addition of AR ligands. Hip overexpression promoted clearance of soluble and RIPA-insoluble AR112Q that formed after addition of the synthetic ligand R1881 (Fig. 1b). As these effects were blocked by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 1c), we conclude that Hip overexpression enhanced client protein degradation. Consistent with this interpretation, this co-chaperone diminished the frequency of androgen-dependent intranuclear inclusions in cells stably expressing tetracycline (tet)-inducible AR112Q (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Hip increases client protein ubiquitination and promotes AR112Q clearance.

(a) Hip promotes nNOS ubiquitination. HEK293T cells transiently expressing nNOS, HA-ubiquitin (HA-Ub) and increasing amounts of Hip were treated with lactacystin (24 hr). nNOS was immunoprecipitated from cytosolic lysates, and Ub-nNOS from three separate experiments was quantified (mean ± SEM). ***P<0.001. (b, c) Hip decreases AR112Q levels. (b) HeLa cells transiently expressing AR112Q and increasing amounts of Hip were treated with R1881 (10 nM) for 24 hr. Lysates were separated into supernatant and 15,000 g pellet fractions, then analyzed by western blot (left) (For uncropped gel images, see Supplementary Figure 12). At right, pelleted AR from three experiments was quantified. n.s. = not significant.(c) HeLa cells were cotransfected with AR112Q and Hip, then treated with R1881 (10 nM) for 24 hrs prior to 8 hr treatment with MG132 (10 μM). (d) Hip diminishes AR112Q aggregates. PC12 cells expressing tet- regulated AR112Q were transfected with FLAG-Hip, then treated with doxycycline and R1881 (10 nM) for 24 hr. AR and FLAG-Hip were visualized by confocal microscopy (left). Scale bar, 10 μm. The expression of Hip significantly decreased the frequency of polyQ AR intranuclear inclusions (right, mean ± SEM).

YM-1 activates binding of Hsp70 to unfolded substrates

These results support a model in which increased affinity of Hsp70 for substrate proteins promotes their ubiquitination and degradation. To further test this notion, we sought an independent means of promoting the ADP-bound form of Hsp70. We focused on a class of small molecules based on the rhodocyanine MKT-077, as this compound selectively pulls down Hsp70s from cell lysates 28,29. Recent NMR studies established that MKT-077 binds with low micromolar affinity to the nucleotide-binding domain of ADP- but not ATP-bound Hsp70 30. Consistent with these NMR findings, MKT-077 was shown to preferentially favor the ADP-bound conformation of Hsp70s 30. Additionally, we recently found that both MKT-077 and a close derivative, YM-1, promotes Hsp70-dependent steps in nNOS maturation 31. These observations suggested that MKT-077 derivatives may be promising probes for pharmacologically favoring the tight binding form of Hsp70, thereby providing a means to test our model of chaperone function in protein triage.

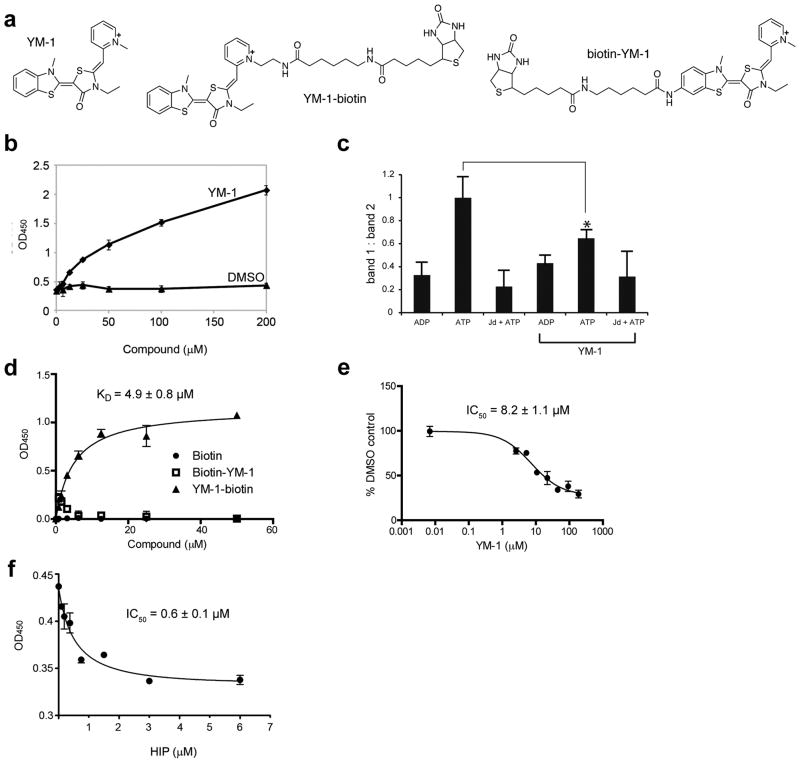

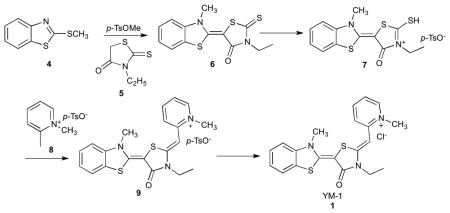

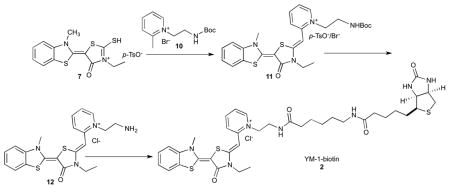

To accomplish this, we synthesized YM-1 (Online Methods; 1), a stable and soluble MKT-077 analog (Fig. 2a). Like MKT-077, YM-1 selectively pulls down Hsp70 from cell lysates (Supplementary Fig. 2). To test whether this compound impacts the apparent binding affinity of Hsp70s, we used an ELISA-like assay to measure binding to denatured luciferase. We found that YM-1 potently stimulated purified Hsp70 binding to its unfolded substrate (Fig. 2b). Next, we performed partial trypsin proteolysis on human Hsp70 after YM-1 treatment. The ATP-bound form of Hsp70 has a characteristic pattern after proteolysis that is distinct from the ADP-bound form (Supplementary Fig. 3). Addition of a J domain, which stimulates ATPase activity, converts the ATP-like digestion pattern to one that resembles the ADP-bound form. Addition of YM-1 (200 μM) partially blocked formation of the ATP-bound form, identical to what was previously observed for MKT-077 30 (Fig. 2c). Together, these studies suggest that YM-1, like MKT-077, converts Hsp70 to its tight affinity conformation. To further explore the binding of YM-1 to Hsp70, we synthesized two biotinylated probes (Fig. 2a). The orientation of MKT-077 bound to Hsp70, as determined by NMR, suggests that the pyridine ring should be solvent exposed 30. To test this idea, we appended a biotin tag to either the pyridine side of the YM-1 (termed YM-1-biotin, 2; Online Methods and Fig. 2a) or the opposite benzothiazole side (biotin-YM-1, 3; Online Methods), which, based on NMR, is expected to be buried. In an ELISA-like format, we found that only 2 had affinity for human Hsp70 (Fig. 2d), with an apparent KD of 4.9 ± 0.8 μM. This interaction appeared to be specific, as unlabelled YM-1 could compete for binding (Fig. 2e). This platform not only provided insight into YM-1 binding to Hsp70, but also allowed us to test whether the co-chaperone Hip could compete with YM-1. Using purified Hip, we found that it could indeed block binding of the YM-1-biotin probe (Fig. 2f), suggesting that these natural and synthetic co-chaperones utilize a similar contact surface. Based on these data, we propose that YM-1 acts similarly to Hip, favoring accumulation of the ADP-bound form of Hsp70 and increasing its apparent affinity for substrates. In an effort to gain further support for this notion, we attempted to generate a number of Hsp70 point mutants that were predicted to disrupt YM-1 binding based on NMR data defining contact sites with MKT-077 30. Unfortunately, we found that these mutants were unstable and degraded, consistent with the observation that the amino acids that contact this small molecule are invariant or highly conserved (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. YM-1 increases Hsp70 binding to a denatured substrate and competes with Hip for binding.

(a) Chemical structures of YM-1 and the two biotinylated probes, 2 and 3. (b) YM-1 promotes binding of Hsp70 to denatured luciferase. Binding of purified Hsp70 to denatured luciferase was measured using an HRP-coupled, anti-Hsp70 antibody. A solvent control is shown for comparison. Data are mean± SEM.(c) Partial trypsin proteolysis shows that YM-1 favors an ADP-like conformation. Full length human Hsp70 was treated with ADP, ATP or ATP and a J domain (Jd). While proteolysis of the ADP-treated sample produces a single characteristic band (band 2), addition of ATP yields an additional fragment (band 1). The ratio of bands 1 and 2 are quantified and the error of duplicate experiments is shown. *P<0.005.(d) Binding of the biotinylated probes to Hsp70 confirms that the pyridine ring of YM-1 is solvent exposed. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. Data are mean ± SEM. (e) Binding of 2 to Hsp70 is specific and can be competed with unlabelled YM-1. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. Data are mean ± SEM.(f) YM-1 and Hip bind competitively to Hsp70. Binding of 2 to immobilized Hsp70 is diminished by pre-incubation with increasing amounts of Hip. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. Data are mean ± SEM.

YM-1 increases ubiquitination and degradation of clients

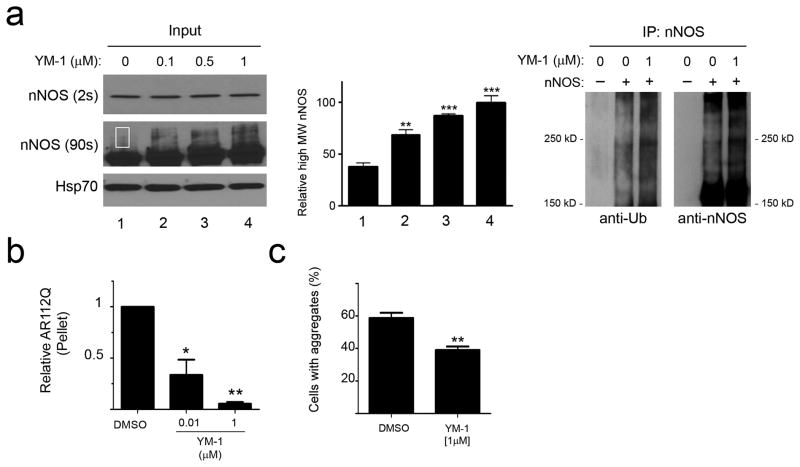

As a first test of the effects of YM-1 on ubiquitination, we treated cells stably expressing nNOS with increasing concentrations of YM-1 in the presence of lactacystin (Fig. 3a). Similar to the effects of Hip overexpression, YM-1 treatment led to a dose-dependent accumulation of high molecular weight, ubiquitinated nNOS species. Additionally, YM-1 diminished polyQ AR levels in tet-inducible PC12 cells, reminiscent of the effects mediated by Hip overexpression (Fig. 3b, c). To explore whether both soluble and insoluble forms of AR112Q were sensitive to this treatment, we added YM-1 and separated these fractions. We found that YM-1 significantly decreased the accumulation of RIPA-insoluble AR112Q (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 4) and diminished the occurrence of AR intranuclear inclusions in the presence of ligand (Fig. 3c). In contrast to this decrease of insoluble and aggregated polyQ AR species, treatment with YM-1 only slightly diminished levels of soluble AR112Q (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that unfolded AR species were most sensitive to its action in this system. We note that Hip may also promote Hsp70 binding to some client proteins in their native conformations, but this effect is less well characterized. Indeed, we found that neither exogenous Hip nor YM-1 promotes association of the glucocorticoid receptor with the Hsp90 chaperone machinery or influences ligand binding by the receptor (Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting that they exert their greatest effects on the interaction of Hsp70 with unfolded proteins.

Figure 3. YM-1 increases client protein ubiquitination and diminishes AR112Q aggregation.

(a) YM-1 promotes nNOS ubiquitination. HEK293 cells stably expressing nNOS were treated with increasing amounts of YM-1 and lactacystin for 24 hours. Short exposure of input (on left) shows unmodified nNOS, while longer exposure shows an accumulation of a higher molecular weight (MW) species representing mono-ubiquitinated nNOS 25 (highlighted in rectangle). (For uncropped gel images, see Supplementary Figure 12) Quantification of mono-ubiquitinated nNOS from four separate experiments is shown in the middle, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Immunoprecipitation (on right) shows increased nNOS poly-ubiquitination in the presence of YM-1. (b) YM-1 decreases insoluble AR112Q. PC12 cells expressing tet-regulated AR112 were treated with R1881 (10 nM) and YM-1 for 16 hours. Pelleted (15,000 g) AR112Q was visualized by immunoblot analysis and data from three separate experiments was quantified (mean ± SEM). *P<0.05, **P<0.01(c) PC12 cells were treated as in (b). AR was visualized by fluorescence microscopy and cells with nuclear inclusions quantified. Data are mean ± SEM. **P<0.01.

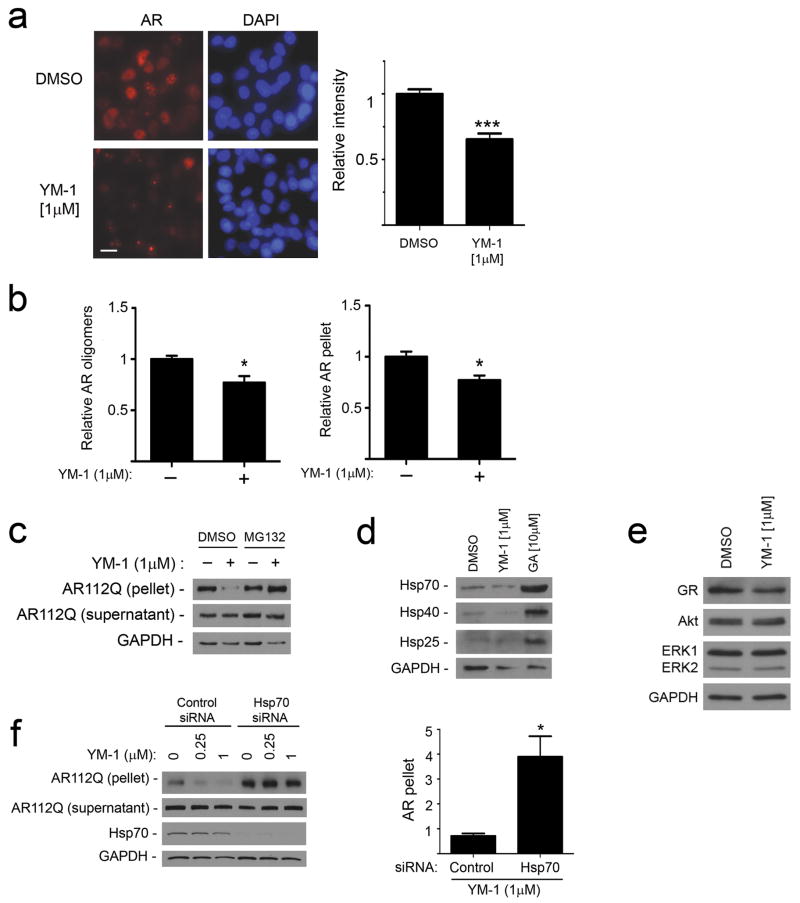

We postulated that YM-1 exerted these effects on polyQ AR levels by increasing protein degradation. To test this notion, we induced AR112Q expression in tet-regulated PC12 cells in the presence of R1881 for 48 hrs to allow for robust expression and ligand-dependent unfolding (Supplementary Fig. 6). This was associated with the formation of intranuclear inclusions that did not stain with the amyloid dye thioflavin S (Supplementary Fig. 7). Transgene expression was then shut off by washing out doxycycline, and cells were incubated for an additional 72 hrs with YM-1 or a solvent control. YM-1 promoted the clearance of AR112Q as reflected by the loss of immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 4a). Immunoblot analysis revealed that YM-1 promoted the clearance of both RIPA-insoluble AR112Q and high molecular weight species that remained in the soluble fraction after ultracentrifugation (Fig. 4b, Supplemenary Fig. 8). These oligomers formed in a hormone-dependent manner and were detected only in cells expressing the polyQ AR (Supplementary Fig. 9). The effects of YM-1 were blocked by MG132 (Fig. 4c), supporting the interpretation that YM-1 enhanced polyQ AR degradation through the proteasome. Unlike chemical inhibitors of Hsp90, such as geldanamycin, YM-1 exerted these effects without increasing the expression of the stress-responsive molecular chaperones Hsp70, Hsp40 or Hsp25 (Fig. 4d) and without markedly altering levels of other client proteins that are in their native conformation (Fig. 4e). Notably, siRNA knockdown of Hsp70 reduced the potency of YM-1, thus identifying Hsp70 as its critical cellular target for these effects (Fig. 4f). In contrast, knockdown of a constitutive form of Hsp110 did not alter the response to YM-1 (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Figure 4. YM-1 increases Hsp70-dependent degradation of AR112Q.

(a) PC12 cells were induced to express AR112Q in the presence of R1881 (10 nM) for 48 hr, washed to remove doxycycline to turn off the transgene, and then incubated in the presence or absence of YM-1. Cells were stained for AR (left). Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of field signal intensity from three experiments (right). Data are mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001 (b) YM-1 promotes clearance of insoluble and oligomeric AR112Q. Signal intensity of AR112Q monomer in the 15,000 g pellet and high MW oligomers in the soluble fraction after ultracentrifugation was quantified from triplicate experiments (mean ± SEM). *P<0.05 (c) Immunoblot of AR112Q in supernatant and pellet shows that effects of YM-1 are blocked by 24 hr treatment with MG132 (10 μM). (For uncropped gel images, see Supplementary Figure 12.)(d) HeLa cells treated with vehicle, YM-1 or geldanamycin (GA) for 24 hr were probed for expression of inducible Hsp70, Hsp40 and Hsp25. (e) Levels of Akt and ERK1/2 are unchanged and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) mildly decreased by treatment of PC12 cells with YM-1, using the lysates probed in panel b.(f) YM-1 effects are dependent upon Hsp70. PC12 cells expressing tet-regulated AR112Q were transfected with siRNAs targeted at inducible Hsp70 or nontargeted control. After 24 hrs, cells were treated with R1881 (10 nM) plus YM-1 or vehicle. Effects of YM-1 on pelleted AR112Q are shown on left and quantified from triplicate experiments on right. Data are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05.

Activating Hsp70 rescues polyQ toxicity in Drosophila

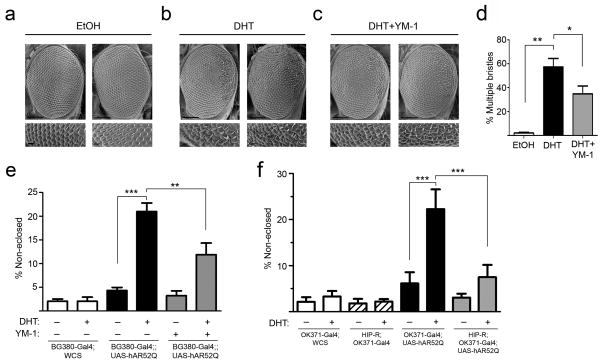

We next wondered whether the reduced accumulation of polyQ AR observed in cells would be associated with decreased proteotoxicity in more complex disease models. We turned to a Drosophila melanogaster model of SBMA in which the UAS/Gal4 system drives expression of the human polyQ AR (hAR52Q) to produce hormone and glutamine length dependent toxicity 32. When hAR52Q was expressed by the eye-specific GMR promoter, flies exhibited a dihydrotestosterone (DHT)-dependent rough eye phenotype characterized by ommatidial degeneration and extranumerary interommatidial bristles, particularly in the posterior aspects of the eye (Fig. 5a,b). We found that DHT-dependent eye degeneration in this line was relatively modest, and was partially rescued by rearing flies on YM-1 (Fig. 5c,d).

Figure 5. Hsp70 allosteric activators rescue toxicity in Drosophila expressing AR52Q.

(a-c) Representative scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) of eyes from GMR-Gal4;UAS-hAR52Q flies reared at 29° C. Lower panels show high magnification images from posterior aspects of eyes. Scale bars: upper panels, 100 μm; lower panels 10 μm. (a) Flies reared on food supplemented with vehicle control. (b) Flies reared on food containing dihydrotestosterone (1 mM DHT). (c) Flies reared on food containing DHT plus YM-1 (1 mM). (d) SEMs were scored for the presence of more than 1 bristle at inter-ommatidial junctions (mean ± SEM, n = 150-200 junctions/condition). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (e) DHT-dependent toxicity is rescued by YM-1. Reported are the percent of pupae that fail to eclose (mean ± SEM, n = 200-800/condition) when reared on DHT or vehicle. Flies compared are BG380-Gal4;;WCS (white bars), BG380-Gal4;;UAS-hAR52Q (black bars), and BG380-Gal4;;UAS-hAR52Q reared on YM-1 (gray bars). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (f) Overexpression of HIP-R suppresses toxicity. Reported are the percent of pupae that fail to eclose (mean ± SEM, n = 200-800/condition) when reared on DHT or vehicle. Flies compared are OK371-Gal4;WCS (white bars), HIP- R;OK371-Gal4 (striped bars), OK371-Gal4;UAS-hAR52Q (black bars), and HIP- R;OK371-Gal4;UAS-hAR52Q (gray bars). ***P<0.001.

While this result was promising, we next sought a more robust phenotype that was mediated by polyQ AR expression in motor neurons to test the effects of targeting Hsp70. Eclosion is the final stage of Drosophila development in which adult flies escape from their pupal case. When hAR52Q was expressed in motor neurons by the BG380 or OK371 promoters, we found that a significant percentage of flies failed to eclose in a DHT-dependent manner (Fig. 5e,f). In contrast, flies expressing the wild-type AR in motor neurons exhibited no hormone-dependent toxicity in this assay (P>0.05, data not shown). Strikingly, DHT-dependent pupal toxicity of the polyQ AR was significantly rescued by rearing flies on YM-1 (Fig. 5e). Finally, we sought to determine whether genetic and chemical manipulation of Hsp70 were similarly effective in this Drosophila model. We found that, as with YM-1 treatment, polyQ AR toxicity was rescued by the presence of a UAS-responsive enhancer element just upstream of the coding sequence of HIP-R (Fig. 5f), a Drosophila ortholog of Hip. Although we considered the possibility that a second UAS might confound this analysis by diminishing polyQ AR expression in these double transgenics, we found that this was not the case (Supplementary Fig. 11). Together, we conclude that allosteric activation of client binding by Hsp70, using either a small molecule or genetic manipulation, rescued toxicity in a Drosophila model of SBMA.

DISCUSSION

Here we sought to manipulate an endogenous cellular protein quality control system that regulates polyQ AR degradation to alleviate the toxicity that underlies a protein aggregation neurodegenerative disorder. For the AR, the major chaperones involved in protein triage decisions are Hsp90 and Hsp70, which act together in a multichaperone machinery to regulate its function, trafficking and turnover 10,12. Prior attempts at targeting this pathway for potential therapeutic benefits have focused primarily on inhibitors of Hsp90 ATPase activity, using compounds such as geldanamycin and its derivatives. Although promising in certain settings, these N-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors activate a stress response and, moreover, lead to the degradation of a number of other Hsp90 clients. More recently described C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors do not induce a stress response 33 and their effects on the polyQ AR have not been explored. In contrast, Hsp70 is less well characterized as a potential drug target 34,35, though this chaperone is appealing because it is poised to recognize the damaged products of Hsp90’s failed attempts at stabilization. Thus, we suggest that targeting Hsp70 might preferentially promote the degradation of substrates that are already misfolded and/or damaged, with less dramatic effects on substrates in native conformations.

Consistent with this notion, the Hsp70 co-chaperone Hip is known to interact with the ATPase domain of Hsp70 and stabilize it in its ADP-bound state 21 to promote binding to unfolded substrates 22. The potential benefit of elevating Hip to influence triage of unfolded proteins was suggested by prior studies showing that its overexpression in cell culture diminishes aggregation of a long glutamine tract 20. Hip overexpression also decreases the formation of fibrils by another Hsp90 client protein, α-synuclein, and its knockdown in C. elegans increases α-synuclein aggregation 36. Here we extended these observations to SBMA. We show that both Hip and YM-1 enhance client protein ubiquitination, stimulate clearance of the polyQ AR, and rescue toxicity in a Drosophila model of SBMA. While Hip overexpression may invoke effects independent of its activity on Hsp70 and, likewise, YM-1 may have yet uncharacterized off-target partners in the cell, the combination of these two probes provides strong, complementary evidence for the idea that the high affinity, ADP-bound form of Hsp70 favors degradation of misfolded substrates. Although we have discussed polyQ AR degradation solely with respect to Hsp70, CHIP and Hip, for ubiquitination of polyQ AR that is already in insoluble aggregates, a disaggregase function of Hsp70 may be required before CHIP and Hip come into play 37.

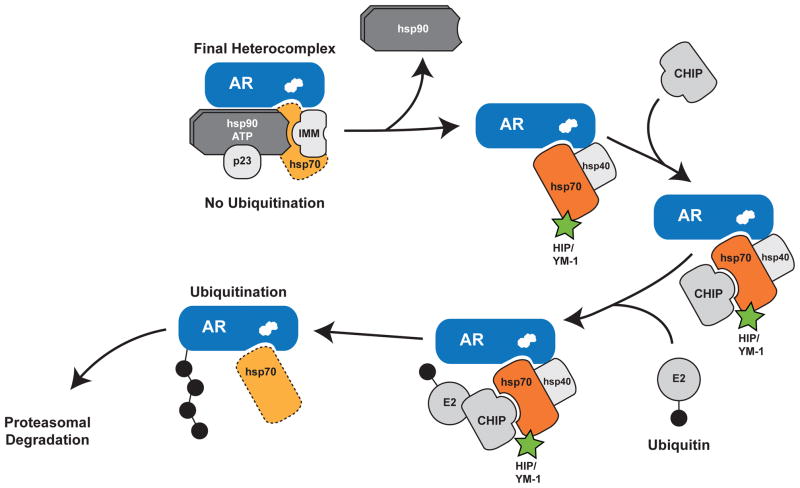

Our findings support a model of chaperone machinery function in quality control whereby Hsp90 and Hsp70 have essentially opposing roles in the triage of unfolded proteins 11,38, in that Hsp70 promotes substrate ubiquitination whereas Hsp90 inhibits ubiquitination (Fig. 6). We envision that as the mutant AR undergoes ligand- and polyQ length-dependent conformational changes, Hsp90 can no longer interact with these unfolded species to inhibit ubiquitination. E3 ligases interacting with substrate-bound Hsp70, such as CHIP, then target ubiquitin-charged E2 enzymes to the unfolded substrate. In this way the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery can function as a comprehensive protein management system for quality control of damaged proteins. Support for this model is provided by the observation that stabilizing the Hsp90-polyQ AR complex by overexpressing the co-chaperone p23 decreases ligand-dependent unfolding and aggregation 13. Furthermore, reducing functional Hsp90 tips this balance, enhancing recruitment of Hsp70-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligases to promote degradation 39. Consistent with this model, we found that levels of the Hsp90 clients Akt and ERK1/2 were unchanged by YM-1 and that the glucocorticoid receptor was only mildly affected by YM-1, indicating that proteins which are in their native conformations and are stabilized by Hsp90 are relatively protected from allosteric activation of Hsp70 binding. In contrast, we demonstrated previously that methylene blue, a compound that inhibits Hsp70 dependent ubiquitination, impairs polyQ AR degradation 24. Together, these findings and the current work suggest that allosteric conversion of Hsp70 to its high affinity, ADP-bound form promotes client protein ubiquitination, enhances clearance of the polyQ AR and alleviates toxicity in SBMA models. Importantly, this suggests new and previously under-appreciated SBMA drug targets in the chaperone system. We suggest that capturing the Hsp70 ADP-bound state could be a promising therapeutic objective. However, many questions remain. For example, what is the toxicity associated with targeting Hsp70s? Neither Hip overexpression nor YM-1 treatment produced gross abnormalities or toxicity in flies, perhaps because the Hsp70-substrate complex fates only previously unfolded substrates for turnover. Yet, the safety of this approach remains to be firmly tested and established.

Figure 6. Model of the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery and regulation of polyQ AR degradation.

Hsp90 and Hsp70 form a heterocomplex to stabilize the polyQ AR, enable ligand binding (depicted as white steroid within AR) and guide intracellular localization (top left). Dissociation of Hsp90 following the addition of small-molecule inhibitors or ligand-dependent conformation change of the polyQ AR permits unfolding of the mutant protein. Substrate-bound Hsp70 then recruits chaperone dependent ubiquitin ligases such as CHIP to promote degradation through the proteasome. We note that CHIP and Hip both bind Hsp70 via tetratricopeptide repeat domains, although it is unknown whether this binding occurs simultaneously. Furthermore, we note that other chaperone dependent ubiquitin ligases may function redundantly with CHIP. We demonstrate here that allosteric activators of Hsp70, including Hip and YM-1 (in green), increase substrate binding affinity, facilitate client protein ubiquitination and promote polyQ AR clearance by the proteasome. This strategy alleviates polyglutamine toxicity by facilitating degradation of the mutant protein. The broken line for Hsp70 in the final heterocomplex indicates that it is present in substoichiometric levels with respect to the receptor. IMM, immunophilin.

In addition to the polyQ AR, other proteins that unfold and aggregate in age- dependent neurodegenerative disorders are also clients of the Hsp90/Hsp70 chaperone machinery. Along with α-synuclein, evidence indicates that huntingtin and tau are also Hsp90 clients 40–42. Accumulation of these unfolded proteins causes a variety of disorders, for which available treatment options are few and limited to measures that are largely supportive. Our model of chaperone machinery function in protein quality control suggests that the strategies identified here for SBMA may have far-reaching applicability. We suggest that, like the use of Hsp90 inhibitors, targeting Hsp70 with allosteric activators of substrate binding may lead to new therapeutic approaches for many of the protein aggregation disorders that occur in the aging population.

ONLINE METHODS

Materials

HeLa cells were from the American Type Culture Collection. PC12 cells expressing tet-inducible forms of the AR were characterized previously 43. Phenol red-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), charcoal-stripped calf serum was from Thermo Scientific Hyclone Products (Waltham, MA) and horse serum was from Invitrogen. Fugene 6 was from Roche (Indianapolis, IN), and DHT and MG132 were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Geldanamycin and the anti-72/73-kDa Hsp70 (N27F3-4), stress-inducible Hsp70, Hsp40, Hsp25 and Hip antibodies were from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The AR (N-20), FLAG, and GAPDH antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), Sigma, and Abcam (Cambridge, MA) respectively. The HRP-tagged secondary antibodies were from Biorad, and the Alexa Flour 594 and 488 conjugated secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. Plasmid encoding Hip was from GeneCopoeia and modified by the addition of a triple FLAG tag. Hsp70 siRNAs were ON-TARGETplus SMART pool rat HSPA1A or non-targeting control (Dharmacon).

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells were grown in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% charcoal/dextran-stripped fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected with 3 μl Fugene 6 and 1 μg DNA. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were pooled and replated, then treated as indicated. PC12 cells were grown in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal/dextran-stripped fetal calf serum, 10% charcoal-stripped horse serum, G418 (Gibco) and hygromycin B (Invitrogen). AR expression was induced with 0.5 μg/mL doxycycline (Clontech). PC12 cells were transfected by electroporation with the Lonza Nucleofector kit. HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM and transfected using Ca2+-phosphate.

Analysis of protein expression

Cells were washed with PBS, harvested, and lysed by sonication in RIPA buffer containing phosphatase and proteinase inhibitors. For analysis of oligomers, cells were lysed in high salt lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 400mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40). Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 15,000 g and protein concentration was determined by a BCA protein assay. Samples for oligomer analysis were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein samples were electrophoresed through 10% SDS-polyacrylamide or 4%–20% gradient gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a semi-dry transfer apparatus. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by chemiluminescence. Signal intensity was normalized to GAPDH, and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH).

nNOS ubiquitination

HEK293T cells were transfected with cDNAs for HA-ubiquitin, nNOS, Hip or vector plasmid. Lysates were collected after 48 hrs for western blot and immunoprecipitation. HEK293 cells stably expressing nNOS were treated with increasing amounts of YM-1 for 24 hrs in the presence of 10 μM lactacystin prior to western blot and immunoprecipitation. Immunoblots were probed as indicated and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ.

Immunofluorescence

PC12 cells were transfected with 3xFLAG-Hip as indicated. Following induction and small molecule treatment, cells were fixed, stained and mounted using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z1 microscope, and nuclear signal intensity was quantified by ImageJ (NIH). Data are from at least 3 fields per condition in 3 experiments. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Zeiss LSM 510-META Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy system.

Chemical Synthesis

Reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Acros and used without purification. Purity of the starting materials was greater than 90% (by 1H NMR) in all instances. All reactions were performed under inert gas in flame-dried glassware. 1H and 13C spectra were obtained at room temperature on a Varian 400-MR instrument operating at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C. Chemical shifts were referenced to solvent peaks: d-H 2.50 and d-C 39.51. Mass spectrometry was obtained on a Micromass LCT time-of-flight mass spectrometer in the ES+ mode. These syntheses were performed as previously described and the characterization of compound 1 and the intermediates (4-9) matched literature precedent 51.

Synthesis of YM-1 (1)

Synthesis of (E)-3-ethyl-5-(3-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one (6)

To 55.2 mmol of 2-(methylthio)-benzothiazole (4) dissolved in 14 mL of anisole was added 81.7 mmol of methyl-p-toluenesulfonic acid. The reaction mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 4 hours. The reaction was cooled down to room temperature and was added 55.2 mmol of 3-ethylrhodanine (5) dissolved in 200 mL of acetonitrile. To the reaction mixture was added dropwise 90.5 mmol of triethylamine and the reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight. The precipitate was filtered, washed with acetonitrile and dried in vacuo to afford 6 as a yellow solid. Yield: 95%

Synthesis of (E)-3-ethyl-5-(3-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)-2-(methylthio)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-3-ium p-toluene sulfonate (7)

To 3.2 mmol of 6 dissolved in 1 mL of dimethylformaide (dry) was added 9.6 mmol of methyl-p-toluenesulfonic acid. The reaction mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 3 hours and the precipitate was filtered and washed with acetone to afford 7 as an orange solid. Yield: 79%

Synthesis of 2-((Z)-((E)-3-ethyl-5-(3-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)-4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)methyl)-1-methylpyridin-1-ium p-toluene sulfonate (9)

2 mmol of compound 7 and 2 mmol of 1,2-dimethylpyridin-1-ium p-toluenesulfonate (8) were dissolved in 10 mL of acetonitrile and warmed to 50 °C. To the reaction mixture was added dropwise 2.8 mmol of triethylamine and the reaction was stirred at 50 °C for 3 hours. The reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature and ethyl acetate was poured in to the mixture. The precipitate was filtered and washed with ethyl acetate to give 9 as a red solid. Yield: 50%

Synthesis of 2-((Z)-((E)-3-ethyl-5-(3-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)-4- oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)methyl)-1-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride (1; YM-1)

Compound 9 was dissolved in a mixture of dichloromethane and methanol (1:1) and passed through Amberlite IRA-400 anion exchange resin (chloride form). The solution was concentrated and dried in vacuo to afford 7 as a red solid. 1H d6-DMSO 8.67 (1H, d, J = 6.3 Hz), 8.26 (1H, t, J = 8.2 Hz), 8.04 (1H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.87 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.49 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.42 (1H, t, J =7.4 Hz), 7.30 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 5.96 (1H, t), 4.14 (3H, s), 4.10, (2H, q, J = 7.4, 6.7 Hz), 4.04 (3H, s), 1.26 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz). 13C d6-DMSO 163.80, 154.42, 150.60, 150.51, 145.33, 142.67, 140.33, 127.01, 125.61, 123.53, 122.80, 122.06, 118.69, 111.72, 84.19, 78.26, 45.18, 38.23, 34.48, 11.87. MS (ESI): calculated for C20H20N3OS2+ [M-Cl−]+ m/z 382.1, found 382.1. Purity: >95 % (determined by 1H NMR).

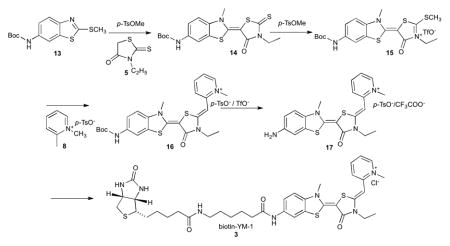

Synthesis of YM-1-biotin (2)

YM-1-biotin was synthesized in a similar manner. Briefly, Boc protected 1-(2-aminoethyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium bromide (10) was coupled with 7 to give 1-(2-aminoethyl)-2-((Z)-((E)-3-ethyl-5-(3-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)-4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)methyl)pyridin-1-ium (11) as a mixture of bromide and tosylate salt. Following Boc deprotection and ion exchange, the compound (12) was conjugated to 6-((biotinoyl)amino)hexanoic acid using standard peptide coupling methods to yield the desired YM-1-biotin (2; YM-1-biotin) as a dark red solid.

Compound 11

1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 8.53 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50-7.40 (m, 2.4H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 0.4H), 6.13 (s, 1H), 4.59 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (s, 3H), 3.46-3.38 (m, 2H), 2.28 (s, 0.6H), 1.30 (s, 9H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). MS (ESI): calculated for C26H31N4O3S2+ [M-Br−/p-TsO−]+ m/z 511.2, found 511.0.

Compound 12

1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 8.84 (s, 2H), 8.77 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50-7.44 (m, 2H), 7.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.00 (s, 1H), 5.00 (m, 2H), 4.23 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.04 (s, 3H), 3.42 (m, 2H), 1.19 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). MS (ESI): calculated for C21H23N4OS2+ [M-Cl−]+ m/z 411.1, found 411.0.

Compound 2

1H d6-DMSO 8.57 (1H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 8.27 (2H, m), 8.06 (1H, d, J = 9.5 Hz), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.77 (1H, m), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.48 (1H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 7.43 (1H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.29 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 6.42 (1H, s), 6.37 (1H, s), 6.18 (1H, s), 4.60 (2H, m), 4.29 (1H, t, J = 5.4 Hz), 4.17 (2H, m), 4.11 (1H, m), 4.04 (3H, s), 3.53 (2H, m), 3.08 (1H, m), 2.97 (2H, dd, J = 6.1, 5.4 Hz), 2.80 (1H, d, J = 4.7, 12.0 Hz), 2.03 (4H, m), 1.59–1.23 (16H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 173.2, 171.8, 163.9, 162.7, 154.3, 150.9, 150.5, 145.3, 143.0, 140.4, 138.9, 127.0, 125.6, 123.5, 122.1, 118.8, 111.7, 106.9, 84.0, 78.3, 61.0, 59.2, 55.4, 39.8, 39.6, 38.2, 38.1, 37.0, 35.4, 35.1, 28.9, 28.2, 28.0, 26.1, 25.3, 24.8, 12.3. MS (ESI): calculated for C37H48N7O4S3+ [M-Cl−]+ m/z 750.3, found 750.1. Purity > 95% by NMR.

Synthesis of biotin-YM-1 (3)

Synthesis of biotin-YM-1 was performed in a similar manner using Boc protected 2-(methylthio)benzo[d]thiazol-6-amine (13) as a starting material. Briefly, coupling of 13 with ethylrhodanine (5) and subsequent conjugation with 1,2-dimethylpyridin-1-ium p-toluenesulfonate (8) gave Boc protected 2-((Z)-((E)-5-(6-amino-3-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)-3-ethyl-4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)methyl)-1-methylpyridin-1-ium (16) as a mixture of tosylate and TFA salt. Following Boc deprotection, 17 was coupled with 6-((biotinoyl)amino)hexanoic acid using standard peptide coupling methods to yield the desired biotin-YM-1 as a mixture of tosylate and TFA salt. The counter ion was exchanged with chloride to afford the final product (3; biotin-YM-1) as a dark red solid.

Compound 13

1H NMR (400 MHz, d-chloroform): δ 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (s, 1H), 3.73 (s, 2H), 2.73 (s, 3H), 1.49 (s, 9H). MS (ESI): calculated for C13H17N2O2S2+ [M+H+]+ m/z 297.1, found 297.0.

Compound 14

1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 1.49 (s, 9H), 1.18 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H). MS (ESI): calculated for C18H22N3O3S3+ [M+H+]+ m/z 424.1, found 424.0.

Compound 15

1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 9.80 (s, 1H), 8.32 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (s, 3H), 4.14 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.04 (s, 3H), 1.50 (s, 9H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). MS (ESI): calculated for C19H24N3O3S3+ [M-TfO−]+ m/z 438.1, found 438.1.

Compound 16

1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 9.60 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.05-7.99 (m, 1H), 7.55-7.40 (m, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (s, 1H), 4.12 (s, 3H), 4.08 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.99 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 9H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). MS (ESI): calculated for C25H29N4O3S2+ [M-TfO−/p-TsO−]+ m/z 497.2, found 497.1.

Compound 17

1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 8.62 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.05-7.99 (m, 1H), 7.60-7.25 (m, 4H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (s, 1H), 4.08 (s, 3H), 4.04 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.99 (s, 3H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). MS (ESI): calculated for C20H21N4OS2+ [M-CF3COO−/TfO−/p-TsO−]+ m/z 397.1, found 397.0.

Compound 3

1H d6-DMSO 8.65 (1H, d, J = 6.4 Hz), 8.24 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 8.15 (1H, s), 8.02 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.76 (2H, m), 7.57 (2H, m), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 5.9 Hz), 6.42 (1H, s), 6.36 (1H, s), 5.94 (1H, s), 4.29 (1H, m), 4.18–4.06 (6H, m), 4.01 (3H, s), 3.08 (1H, m), 3.02 (2H, m), 2.81 (1H, dd, J = 4.9, 11.7 Hz), 2.31 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.03 (2H, t, J =7.3 Hz), 1.65–1.18 (16H, m). 13C NMR (150 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 174.4, 171.8, 163.7, 162.7, 154.2, 150.7, 150.6, 145.2, 142.6, 140.0, 126.0, 123.4, 122.7, 118.5, 112.1, 111.8, 109.5, 84.0, 78.4, 61.0, 59.4, 59.1, 55.4, 46.0, 38.3, 38.2, 36.2, 35.2, 33.6, 29.0, 28.2, 28.0, 26.1, 25.3, 24.8, 14.1. MS (ESI): calculated for C36H46N7O4S3+ [M-Cl−]+ m/z 736.3, found 736.0. Purity > 95% by NMR.

Pulldown of Hsp70 from lysates

HeLa cell lysates (80 μg) were pre-cleared with blank streptavidin agarose resin for 10 minutes and then incubated with YM-1-biotin (500 μM) or biocytin at 4°C overnight in binding buffer (20 mM Tris, 20 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM ADP, 0.01% Tween-20, pH 7.5). These mixtures were subsequently incubated with 200 μL streptavidin agarose beads (Novagen) for 2 hrs at 4°C in a centrifuge column. The flow through was collected by centrifuging the column at 1000 rpm for 1 min. The beads were subsequently washed with 100 μL binding buffer six times (W1-W6). The beads were then boiled for 15 min in SDS loading buffer to remove any remaining proteins (Bds) and the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and silver staining.

Luciferase Binding Assay

Binding of Hsp70 to immobilized firefly luciferase was performed as previously described 44. YM-1 was added from a stock solution of 2.5 mM and diluted to a final DMSO concentration of 4%. YM-1 and an enzyme mix (0.4 μM DnaK, 0.7 μM DnaJ and 1 mM ATP) were pre-incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to incubation with immobilized luciferase. All results were compared to an appropriate solvent control. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Hip competition binding assay

Human Hsp70 and Hip were purified as previously described 45,46 and the Hsp70-binding assay was carried out using an adaptation of a previously described assay 47. Briefly, Hsp70 (2.3 μM, with ADP) was immobilized on ELISA plates (ThermoFisher brand, clear, non-sterile, flat bottom). The treated wells were pre-incubated with Hip (0 – 6 μM) for 5 min prior to addition of biotin-labeled MKT, a probe of the YM-1 binding site 30. The labeled probe was incubated in binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2 and 0.05% Triton X-100) in the wells for 2 hrs at room temperature, followed by three washes with 150 μL Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) and incubation with 100 mL 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST for 5 min. The BSA solution was discarded and the wells were incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase for 1 hr. Following three additional washes with TBST, the wells were incubated with 100 μL 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 30 min. After addition of stop solution, the absorbance was read in a SpectraMax M5 plate reader at 450 nm. Results were compared to control wells lacking Hsp70. Experiments were performed in triplicate and at least two independent trials were performed for each condition.

Partial proteolysis

Proteolysis of human Hsp70 was carried out as described 30 using 200 μM of YM1.

Drosophila stocks and phenotypes

The following strains were used in this study: White Canton-S (wild type), BG380-Gal4 48, GMR-Gal4 49, OK371-Gal4 50, HIPEY14563 (Bloomington), HIP-REY01382 (Bloomington). UAS-hAR52Q flies were provided by Ken-ichi Takeyama 32.

Drosophila stocks were maintained on yeast glucose media at 25°C and experimental flies were kept on Jazz-Mix food at 29°C. Food was cooled to <50°C, then supplemented with 1 mM DHT, 1 mM YM-1, or vehicle (ethanol) control. The eclosion phenotype was scored by marking existing pupal cases at 10 days post addition of parents. Following 7 days at 29°C, the percentage of marked pupal cases that failed to eclose was determined for 200-800 flies of each condition. Scanning electron micrographs were captured by the University of Michigan Microscopy & Image Analysis Core on 1 - 2 day old GMR-Gal4;UAS-hAR52Q adult female flies reared on food supplemented as indicated. Quantification was performed on SEMs from 3 flies for each condition by determining the percentage of inter-ommatidial junctions with more than 1 bristle.

Statistics

Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test, or unpaired Student’s t- test using the software package Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Satya Reddy, Jennifer Diep and Travis Washington for technical assistance, and Ken-ichi Takeyama and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly strains. This work was initiated under a grant from the McKnight Foundation (to APL) and was supported by the N.I.H. (NS055746, NS055746-04S1 to APL; NS059690 to JEG; GM077430 to YO; NS069844 to CAC; NS32214 to DEM; NS076189 to JPC), the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA238924 to APL) and the National Science Foundation (IOS-0842701 to CAC).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AMW, SK, YM, HMP, JCC, WBP, YO, CAC, JEG and APL designed the experiments. AMW, SK, YM, HMP, JPC, TK, XL and YM performed the experiments. AMW, SK, YM, HMP, JPC, TK, WBP, YO, CAC, JEG and APL interpreted the data.

YO, JEG and DEM contributed reagents or analytical tools. AMW, WBP, JEG and APL wrote the paper.

Competing Financial Interest Statement:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Zoghbi HY, Orr HT. Glutamine repeats and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:217–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy WR, Alter M, Sung JH. Progressive proximal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy of late onset. A sex-linked recessive trait. Neurology. 1968;18:671–680. doi: 10.1212/wnl.18.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobue G, et al. X-linked recessive bulbospinal neuronopathy. A clinicopathological study. Brain. 1989;112:209–232. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mhatre AN, et al. Reduced transcriptional regulatory competence of the androgen receptor in X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Nat Genet. 1993;5:184–188. doi: 10.1038/ng1093-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman AP, Harmison G, Strand AD, Olson JM, Fischbeck KH. Altered transcriptional regulation in cells expressing the expanded polyglutamine androgen receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1967–1976. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranganathan S, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:27–42. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCampbell A, et al. CREB-binding protein sequestration by expanded polyglutamine. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2197–2202. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.14.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Z, Wang AM, Robins DM, Lieberman AP. Altered RNA splicing contributes to skeletal muscle pathology in Kennedy disease knock-in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:500–507. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp MQ, et al. Impaired motoneuronal retrograde transport in two models of SBMA implicates two sites of androgen action. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4475–4490. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratt WB, Toft DO. Regulation of signaling protein function and trafficking by the hsp90/hsp70-based chaperone machinery. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:111–133. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratt WB, Morishima Y, Peng HM, Osawa Y. Proposal for a role of the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery in making triage decisions when proteins undergo oxidative and toxic damage. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:278–289. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratt WB, Morishima Y, Osawa Y. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery regulates signaling by modulating ligand binding clefts. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22885–22889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800023200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas M, et al. Pharmacologic and genetic inhibition of hsp90-dependent trafficking reduces aggregation and promotes degradation of the expanded glutamine androgen receptor without stress protein induction. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1876–1883. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokui K, et al. 17-DMAG ameliorates polyglutamine-mediated motor neuron degeneration through well-preserved proteasome function in a SBMA model mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;18:898–910. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waza M, et al. 17-AAG, an Hsp90 inhibitor, ameliorates polyglutamine-mediated motor neuron degeneration. Nat Med. 2005;11:1088–1095. doi: 10.1038/nm1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi Y, et al. Chaperones Hsp70 and Hsp40 suppress aggregate formation and apoptosis in cultured neuronal cells expressing truncated androgen receptor protein with expanded polyglutamine tract. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8772–8778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey CK, Andriola IF, Kampinga HH, Merry DE. Molecular chaperones enhance the degradation of expanded polyglutamine repeat androgen receptor in a cellular model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:515–523. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adachi H, et al. Heat shock protein 70 chaperone overexpression ameliorates phenotypes of the spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy transgenic mouse model by reducing nuclear-localized mutant androgen receptor protein. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2203–2211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02203.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adachi H, et al. CHIP overexpression reduces mutant androgen receptor protein and ameliorates phenotypes of the spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy transgenic mouse model. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5115–5126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1242-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howarth JL, Glover CP, Uney JB. HSP70 interacting protein prevents the accumulation of inclusions in polyglutamine disease. J Neurochem. 2009;108:945–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hohfeld J, Minami Y, Hartl FU. Hip, a novel cochaperone involved in the eukaryotic Hsc70/Hsp40 reaction cycle. Cell. 1995;83:589–598. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer MP, Brehmer D, Gassler CS, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperone machines. Adv Protein Chem. 2001;59:1–44. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)59001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchberger A, et al. Nucleotide-induced conformational changes in the ATPase and substrate binding domains of the DnaK chaperone provide evidence for interdomain communication. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16903–16910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang AM, et al. Inhibition of hsp70 by methylene blue affects signaling protein function and ubiquitination and modulates polyglutamine protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15714–15723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clapp KM, et al. C331A mutant of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase is labilized for Hsp70/CHIP (C terminus of HSC70-interacting protein)-dependent ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33642–33651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng HM, et al. Ubiquitylation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by CHIP, a chaperone-dependent E3 ligase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52970–52977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bender AT, Demady DR, Osawa Y. Ubiquitination of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17407–17411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadhwa R, et al. Selective toxicity of MKT-077 to cancer cells is mediated by its binding to the hsp70 family protein mot-2 and reactivation of p53 function. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6818–6821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tikoo A, et al. Treatment of ras-induced cancers by the F-actin-bundling drug MKT-077. Cancer J. 2000;6:162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rousaki A, et al. Allosteric drugs: the interaction of antitumor compound MKT-077 with human Hsp70 chaperones. J Mol Biol. 2011;411:614–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morishima Y, et al. Heme-dependent activation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by cytosol is due to an Hsp70-dependent, thioredoxin-mediated thiol-disulfide interchange in the heme/substrate binding cleft. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7146–7156. doi: 10.1021/bi200751t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeyama K, et al. Androgen-dependent neurodegeneration by polyglutamine-expanded human androgen receptor in Drosophila. Neuron. 2002;35:855–864. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00875-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burlison JA, Neckers L, Smith AB, Maxwell A, Blagg BS. Novobiocin: redesigning a DNA gyrase inhibitor for selective inhibition of hsp90. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15529–15536. doi: 10.1021/ja065793p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans CG, Chang L, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) as an emerging drug target. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4585–4602. doi: 10.1021/jm100054f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patury S, Miyata Y, Gestwicki JE. Pharmacological targeting of the Hsp70 chaperone. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:1337–1351. doi: 10.2174/156802609789895674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roodveldt C, et al. Chaperone proteostasis in Parkinson's disease: stabilization of the Hsp70/alpha-synuclein complex by Hip. EMBO J. 2009;28:3758–3770. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shorter J. The mammalian disaggregase machinery: Hsp110 synergizes with Hsp70 and Hsp40 to catalyze protein disaggregation and reactivation in a cell-free system. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng HM, Morishima Y, Pratt WB, Osawa Y. Modulation of the heme/substrate-binding cleft of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase regulates binding of Hsp90 and Hsp70 and nNOS ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1556–1565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morishima Y, et al. CHIP deletion reveals functional redundancy of E3 ligases in promoting degradation of both signaling proteins and expanded glutamine proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3942–3952. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldo B, et al. A screen for enhancers of clearance identifies huntingtin as an heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) client protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;287:1406–1414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrucelli L, et al. CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:703–714. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dou F, et al. Chaperones increase association of tau protein with microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:721–726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242720499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walcott JL, Merry DE. Ligand promotes intranuclear inclusions in a novel cell model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50855–50859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang L, et al. Chemical screens against a reconstituted multiprotein complex: myricetin blocks DnaJ regulation of DnaK through an allosteric mechanism. Chem Biol. 2011;18:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang L, Thompson AD, Ung P, Carlson HA, Gestwicki JE. Mutagenesis reveals the complex relationships between ATPase rate and the chaperone activities of Escherichia coli heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70/DnaK) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21282–21291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.124149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanelakis KC, et al. hsp70 interacting protein Hip does not affect glucocorticoid receptor folding by the hsp90-based chaperone machinery except to oppose the effect of BAG-1. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14314–14321. doi: 10.1021/bi001671c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyata Y, et al. High-throughput screen for Escherichia coli heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70/DnaK): ATPase assay in low volume by exploiting energy transfer. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:1211–1219. doi: 10.1177/1087057110380571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Budnik V, et al. Regulation of synapse structure and function by the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg. Neuron. 1996;17:627–640. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freeman M. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1996;87:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahr A, Aberle H. The expression pattern of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter: a marker protein for motoneurons and glutamatergic centers in the brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawakami, et al. Structure-activity of novel rhodacyanine dyes as antitumor agents. J Med Chem. 1998;41:130–142. doi: 10.1021/jm970590k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.