Abstract

Introduction

Psychiatric co-morbidity, in particular major depression and anxiety is common in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Prior studies examining this may be confounded by the co-existence of functional bowel symptoms. Limited data exists examining an association between depression or anxiety and disease-specific endpoints such as bowel surgery.

Methods

Using a multi-institution cohort of patients with CD and UC, we identified those who also had co-existing psychiatric co-morbidity (major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety). After excluding those diagnosed with such co-morbidity for the first time following surgery, we used multivariate logistic regression to examine the independent effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on IBD-related surgery and hospitalization. To account for confounding by disease severity, we adjusted for a propensity score estimating likelihood of psychiatric co-morbidity influenced by severity of disease in our models.

Results

A total of 5,405 CD and 5,429 UC patients were included in this study; one-fifth had either major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety. In multivariate analysis, adjusting for potential confounders and the propensity score, presence of mood or anxiety co-morbidity was associated with a 28% increase in risk of surgery in CD (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.03 – 1.57) but not UC (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.80 – 1.28). Psychiatric co-morbidity was associated with increased healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

Depressive disorder or generalized anxiety is associated with a modestly increased risk of surgery in patients with CD. Interventions addressing this may improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, depression, surgery, hospitalization

INTRODUCTION

Depression and anxiety are common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)1–3. Perceived stress, major life events, and severity of depressive symptoms increase risk of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)4–6. While active disease itself is associated with both depression and anxiety, evidence supports a potential independent effect of stress on influencing risk of relapse5–12. As well, the effect of perceived stress appears to be mainly exerted through the mood components, suggesting that psychiatric co-morbidity may influence natural history of CD and UC13. In mouse models of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) induced colitis, induction of depression through intraventricular injection of reserpine resulted in reactivation of quiescent colitis which could be prevented by administering desmethylimipramine, an antidepressant14.

Psychiatric co-morbidity has been mostly examined in the context of its effect on health-related quality of life in CD and UC15, 16. However, the few studies that have previously examined the effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on disease activity, in particular, on the subsequent course of CD and UC, have several limitations including reliance on symptom-based disease activity indices that often correlate poorly with objective disease activity and short duration of follow-up2, 6, 7, 17–20. In addition, while a wealth of literature exists regarding the healthcare costs associated with anxiety and depression in a primary care population or in other chronic diseases including asthma, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, limited data exists for IBD patients11, 21–28.

The aims of our study were as follows - (1) to examine the frequency of depression and anxiety (prior to surgery or hospitalization) in a large multi-institution electronic medical record (EMR) based cohort of CD and UC patients; (2) to define the independent effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on risk of subsequent surgery or hospitalization in CD and UC; and (3) to identify the effect of depression and anxiety on healthcare utilization in our cohort. We hypothesize that psychiatric co-morbidity is an independent risk factor for more aggressive disease behavior in CD and UC.

METHODS

Study Population

Our study consisted of an EMR based cohort of patients with CD or UC seen at two large tertiary referral hospitals in metropolitan Boston serving over 4 million patients. The details regarding the creation of our cohort have been described previously29. In brief, we first captured all patients with at least one International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) diagnosis code for CD or UC (n = 24,182) (dates ranging from March 1988 – June 2010). From this cohort, using a combination of ICD-9 codes and free text terms identified through natural language processing, we developed an algorithm with a 97% positive predictive value (PPV) in accurately identifying patients with CD or UC. The PPV of this algorithm was confirmed through further chart review by a board certified gastroenterologist (A.N.A) and resulted in a cohort of 5,506 patients with CD and 5,522 patients with UC.

For this study, we first identified patients with co-existing diagnosis codes for depressive disorders (ICD-9 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0x, 311) or generalized anxiety (ICD-9 293.84, 300.0x, 313.0x) using both the presence of such codes as well as the date of first occurrence of the above codes1, 30. To validate the accuracy of the ICD-9 codes for depression and anxiety in our cohort, we selected a random subset of 100 patients with each of these codes and reviewed the medical records. We found the PPV for a diagnosis of depression or anxiety to be 92% and 90% respectively. Next, we identified patients who had undergone any bowel resection identified using appropriate ICD-9 codes (Supplementary Table 1), and the date of occurrence of such resections (n = 1,334). We excluded patients who had their first date of diagnosis code for anxiety or depression following the date of first surgery resulting in 2,040 patients (19%) with CD or UC who had either anxiety or depression prior to their surgery. Our primary predictor variable was a composite of the presence of either depression or anxiety prior to surgery for CD or UC13. In addition, we analyzed depression and anxiety separately.

Variables and Outcomes

Information was obtained on patient age, age at first diagnosis code for CD or UC, gender, non-IBD co-morbidity measured using the Deyo modification of the Charlson score based on ICD-9 codes31 (excluding variables related to psychiatric co-morbidity), and duration of follow-up within our healthcare system. Information was also obtained on the presence of disease-related complications prior to surgery including fistulizing or stricturing disease, and perianal disease using ICD-9 codes (Supplementary Table 1). Use of medications including immunomodulators (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate), anti-tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNF) therapies (infliximab, adalimumab), and corticosteroids (prednisone, budesonide) was ascertained as codified data using the electronic prescription function of our EMR. Similar to disease complication, medication use was ascertained prior to surgery. To adjust for intensity of healthcare utilization, we summed the ‘number of facts’ with each ‘fact’ representing a distinct medical encounter that may include office visits, laboratory test, radiology studies, and inpatient or outpatient procedures. Dividing this by duration of follow-up yielded a ‘fact density’ which served as a measure of healthcare utilization per unit time of follow-up. Since increased healthcare utilization prior to surgery in those with severe disease could result in a greater number of diagnosis codes overall, our multivariate models adjusted for fact density.

Our primary outcome variables were occurrence of one or more IBD-related surgeries, IBD-related hospitalizations (primary discharge diagnosis of CD or UC), and all-cause hospitalizations. IBD-related surgeries were identified through the appropriate ICD-9 codes (Supplementary Table 1) while IBD-related hospitalizations were those with a primary discharge diagnosis of CD or UC. For examination of the association of pre-existing depression and anxiety on hospitalizations, we excluded patients who were noted to have the above co-morbidities after their date of first hospitalization. Our secondary outcomes included number of outpatient visits, number of visits to gastroenterologists, number of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans, and lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies. Radiologic and endoscopic studies were identified using the relevant current procedural terminology (CPT) codes.

Statistical Analysis

All data was analyzed using Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations while categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The t-test was used to compare continuous variables with the chi-square test being used for comparison of categorical variables. To address confounding by disease severity, we developed a propensity score. Propensity scores are used to adjust for non-random distribution of variable of interest in observational studies to reduce the effect of known potential confounders that may be associated both with the exposure and outcome. As disease severity could be an important risk factor for both psychiatric comorbidity (exposure) and surgery or hospitalizations (outcome), we developed a propensity score to estimate an individual’s likelihood of developing depression or anxiety given known or potential risk factors for such psychiatric co-morbidity. These was developed using a logistic regression model with the predictors being demographic (age, gender, Charlson co-morbidity), disease (IBD type, presence of fistulae, stricture, perianal disease), and treatment (need for anti-tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNF) or immunomodulator therapies) factors. We further confirmed that our propensity score was adequately able to predict psychiatric co-morbidity such that the difference between the propensity scores between patients with and without depression or anxiety was significantly different statistically at p < 0.0001 for both the CD and UC. We adjusted for this propensity score in all our multivariate models to account for non-random occurrence of anxiety and depression, to arrive at a more accurate estimate of the independent effect of psychiatric comorbidity on our outcome of interest. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the independent effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on likelihood of subsequently undergoing IBD-related surgery, all-cause, or IBD-related hospitalizations while controlling for potential confounders. For outcomes that were on the continuous scale, multivariate linear regression analysis was used. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was indicative of statistical significance. Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners Healthcare.

RESULTS

Study Population

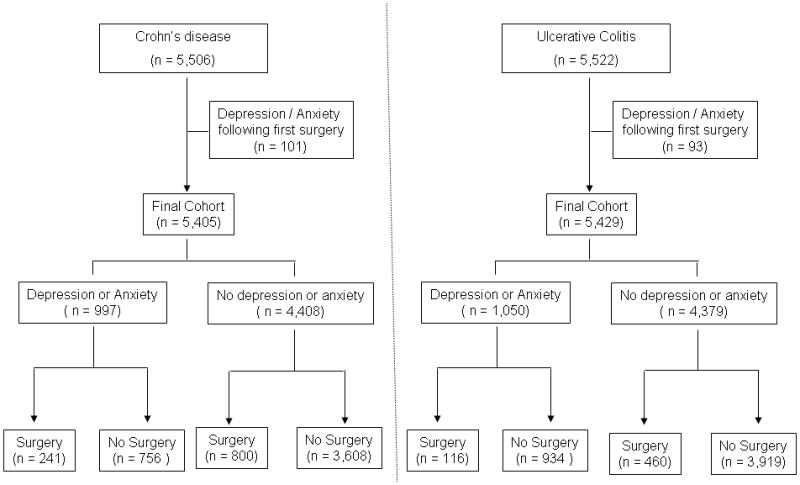

There were 5,405 patients with CD included in the study among whom 997 (18%) were noted to have diagnosis codes for depression or anxiety prior to their first surgery (Figure 1). Similarly, 1,050 (19%) out of 5,429 UC patients had depression or anxiety prior to their first surgery. Approximately 40% of patients with a diagnosis of depression also had a diagnosis of anxiety disorders. The mean interval between the date of first diagnosis code for anxiety or depression and surgery among CD patients was 19 months while that for UC was 17 months. CD patients with psychiatric co-morbidity were likely to be older at the time of their first encounter for CD (42 vs. 39 years), had a greater modified Charlson score (2.7 vs. 1.1) and were more likely to be women (62% vs. 52%) than those without such psychiatric co-morbidity (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) (Table 1). As well in the UC cohort, patients with psychiatric co-morbidity were more likely to be older, female, and have a greater non-IBD co-morbidity burden that those without psychiatric diagnoses.

Figure 1.

Flowchart demonstrating development of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis cohorts

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Characteristic | With psychiatric co- morbidity | Without psychiatric co-morbidity | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease | (n = 997) | (n = 4,408) | |

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 49.5 (17.7) | 44.7 (19.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age at first IBD diagnosis code (mean (SD)) | 42.0 (17.7) | 38.5 (18.8) | < 0.001 |

| Female (%) | 62 | 52 | < 0.001 |

| Modified Charlson score (mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.5) | 1.1 (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of follow-up in years (mean (SD)) | 11.5 (6.8) | 7.7 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| Penetrating disease | 7% | 6% | 0.10 |

| Stricturing disease | 12% | 8% | < 0.001 |

| Perianal disease | 16% | 12% | 0.001 |

| Ulcerative colitis | (n = 1,050) | (n = 4,379) | |

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 52.7 (18.3) | 47.9 (18.5) | < 0.001 |

| Age at first IBD diagnosis code (mean (SD)) | 45.2 (17.8) | 41.1 (18.1) | < 0.001 |

| Female (%) | 66 | 50 | < 0.001 |

| Modified Charlson score (mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.5) | 1.1 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of follow-up in years (mean (SD)) | 12.5 (6.7) | 9.1 (6.8) | < 0.001 |

IBD – Inflammatory bowel diseases; SD – standard deviation

Risk of surgery

CD patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety were significantly more likely to require surgery than those without such co-morbidity (24% vs. 18%, p < 0.001, univariate OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.22 – 1.69) (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, adjusting for current age, age at first diagnosis code for IBD, gender, Charlson co-morbidity score, duration of follow-up, and propensity score, presence of psychiatric co-morbidity prior to surgery was associated with a 28% increase in risk of surgery (Adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 – 1.57)) (Table 2). Further adjustment for use of anti-TNF or immunomodulator therapy prior to surgery did not attenuate the effect of psychiatric co-morbidity (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01 – 1.47). In contrast, there was no effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on risk of surgery in UC (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.80 – 1.28). Stratifying by gender, the effect of depression or anxiety on CD-related surgery was more prominent in women (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.02 – 1.62) than men (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.85 – 1.47), and in those who were older than the median of 44 years at first encounter for IBD (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.08 – 1.85) than those younger than this age (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.80 – 1.29). The effect of anxiety on risk of surgery in CD (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.05 – 1.75) was numerically greater than that of depression than that of depression (OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.95 – 1.53) but this difference was not statistically significant. Neither diagnosis individually affected risk of surgery in UC. Adjusting for occurrence of outpatient or gastroenterologist office visits did not alter the odds ratios.

Table 2.

Effect of psychological co-morbidity on outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Outcome | With psychiatric co-morbidity % | Without psychiatric co-morbidity % | Adjusted odds ratio† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease | |||

| Surgery | 24 | 18 | 1.27 (1.03 – 1.58) |

| IBD-related hospitalization | 54 | 33 | 1.05 (0.88 – 1.26) |

| All-cause hospitalization | 83 | 54 | 1.48 (1.19 – 1.83) |

| Corticosteroids use | 56 | 34 | 1.83 (1.57 – 2.13) |

| Immunomodulator use | 37 | 28 | 1.43 (1.21 – 1.67) |

| Anti-TNF agent use | 19 | 16 | 1.17 (0.96 – 1.43) |

| Ulcerative colitis | |||

| Surgery | 11 | 10 | 1.01 (0.80 – 1.29) |

| IBD-related hospitalization | 28 | 22 | 0.77 (0.63 – 0.93) |

| All-cause hospitalization | 74 | 49 | 1.28 (1.07 – 1.52) |

| Corticosteroids use | 44 | 31 | 1.42 (1.22 – 1.64) |

| Immunomodulator use | 20 | 18 | 1.16 (0.97 – 1.39) |

| Anti-TNF agent use | 7 | 6 | 1.15 (0.86 – 1.53) |

IBD – Inflammatory bowel diseases; TNF – tumor necrosis factor

Adjusted for age, age at first diagnosis code for IBD, gender, modified Charlson co-morbidity index, duration of follow-up, and propensity score

Hospitalizations and medication use

Depression or anxiety did not increase likelihood of IBD-related hospitalizations in CD (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.88 – 1.26) and indeed modestly reduced likelihood of UC-related hospitalizations (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63 – 0.93). However, all-cause hospitalizations were increased in the presence of psychiatric co-morbidity for both CD (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.19 – 1.83) and UC (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.07 – 1.52). In CD, presence of depression or anxiety was associated with an increased likelihood of anti-TNF therapy (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.96 – 1.43), immunomodulators (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.21 – 1.67), and corticosteroids (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.58 – 2.13). In UC, psychiatric co-morbidity was associated with steroid use (OR 1.42, 95% CI 122 – 1.64) but not immunomodulators (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.97 – 1.39) or anti-TNF agents (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.87 – 1.53).

Healthcare utilization

A greater proportion of CD patients with underlying anxiety and depression underwent an abdominal CT scan (66% vs. 41%, p < 0.001) or colonoscopic evaluation (58% s. 47%, p < 0.001) than those without psychiatric co-morbidity. The mean number of CT scans per patient was greater in those with depression or anxiety than those without (2.1 vs. 0.9, p < 0.001) as were the mean number of colonoscopies (2.5 vs. 1.9, p < 0.001) (Table 3), a difference that persisted after adjusting for duration of follow-up. Patients with psychiatric co-morbidity also had significantly greater number of total outpatient visits with an IBD diagnosis, as well as visits to gastroenterologists compared to those without psychiatric co-morbidity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of psychological co-morbidity on Healthcare utilization of patients with Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative colitis

| Outcome | With psychiatric co- morbidity Mean (SD) | Without psychiatric co- morbidity Mean (SD) | Adjusted regression co- efficient† (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease | |||

| Number of outpatient visits with CD diagnosis | 19 (25) | 11 (18) | 2.80 (1.54 – 4.06) |

| Number of gastroenterologist visits with CD diagnosis | 9 (14) | 6 (10) | 1.54 (0.84 – 2.25) |

| Number of abdominal CT or MRI scans | 4 (6) | 2 (4) | 1.06 (0.77 – 1.34) |

| Number of lower GI endoscopies | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 0.56 (0.33 – 0.79) |

| Ulcerative colitis | |||

| Number of outpatient visits with UC diagnosis | 10 (13) | 7 (10) | 1.43 (0.73 – 2.14) |

| Number of gastroenterologist visits with UC diagnosis | 5 (8) | 4 (7) | 0.72 (0.24 – 1.20) |

| Number of abdominal CT or MRI scans | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 0.69 (0.40 – 0.90) |

| Number of lower GI endoscopies | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 0.50 (0.24 – 0.75) |

CD – Crohn’s disease, UC – ulcerative colitis, CT – computed tomography, MRI – magnetic resonance imaging

Adjusted for age, age at first diagnosis code for IBD, gender, modified Charlson co-morbidity index, duration of follow-up, and propensity score

DISCUSSION

Depression and anxiety occur in a significant proportion of patients with CD and UC1–3. Prior studies have mostly examined the effect of such psychiatric co-morbidity on symptom-based activity indices and health-related quality of life15, 16, both of which may be confounded by the co-existence of functional symptoms32–34. Using disease-specific hard endpoints, we demonstrate that co-existing psychiatric co-morbidity was independently associated with a modestly increased risk of surgery in CD with a stronger effect for anxiety. In addition, such psychiatric co-morbidity was also associated with several measures of increased healthcare utilization.

The prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity in our cohort was greater than that identified among younger CD patients, and was only slightly lower than that identified through structured questionnaires in two Canadian studies1, 2, 35. However, studies utilizing detailed psychiatric interview have found the prevalence to be as high as 60% reflecting variations in methods used to ascertain these diagnoses, populations studied (tertiary referral center vs. population-based cohorts), severity of disease in the underlying population, and time frame of study.

There is considerable interest in the role of stress and psychiatric co-morbidity in triggering relapses in CD and UC5–8, 10, 11, 36, 37. In mice models of colitis, induction of depression is associated with reactivation of quiescent inflammation14. Epidemiologically, this hypothesis has been examined using cross-sectional and prospective studies. However, there exists significant heterogeneity in ascertainment of exposure and outcomes. In a prospective study of 101 CD patients with a 1 year follow-up, Bitton et al. demonstrated that patients with lower stress and lower scores on avoidance coping were less likely to relapse than those with higher perceived stress17. As subsequently demonstrated by Camara et al., the association between perceived stress and exacerbation of CD may be influenced more by mood (depression and anxiety) than non-mood components, making it important to examine whether depression or anxiety are independent risk factors for more severe disease13.

In the present study, we demonstrate that a diagnosis of depression or anxiety prior to surgery was independently associated with a modestly increased risk for subsequent surgery in CD after adjusting for potential confounders in a propensity-score adjusted model. By excluding patients who had their first diagnosis code for depression or anxiety following their surgery, we minimized the possibility of ‘reverse causality’ whereby having surgery or hospitalization increases risk of depression or anxiety. In addition, adjusting for medication use prior to surgery as a marker of disease severity, we found our estimates of the association between psychiatric co-morbidity and surgery remained unchanged, further supporting the independent effect of such factors. Finally, consistent with this direction of effect, we also found an association with increased use of corticosteroids, immunosuppressive or anti-TNF biologic therapy in CD patients with coexisting depression or anxiety, and corticosteroid use in UC patients.

There have been only a few prior studies that have examined the effect of depression on disease course prospectively. Mardini et al. demonstrated that depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with increased disease activity in CD over a 2-year follow-up38. Similarly, Mittermaier et al., in a mixed cohort of UC and CD patients identified a correlation between depression scores at baseline and number of relapses over an 18 month follow-up39. Thus, our findings are consistent with this prior literature. In contrast, in a cohort comprising 59 IBD patients (32 CD) followed over 1 year, baseline depression or anxiety was not associated with number of relapses though arguably the power to detect a significant association in such a small sample is limited40. One challenge in interpreting prior studies has been the reliance on symptom-based measures of disease activity which may correlate poorly with objective markers of inflammation and could be influenced by the co-existence of functional symptoms32–34. Indeed, disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may be common in patients with CD and UC, and could influence interpretation of symptom-based disease activity scores, particularly in the setting of depression. Thus, facilitated by our longer duration of follow-up, our findings extend the results of the prior studies that were restricted to symptomatic flares to include disease-specific hard endpoints such as the need for IBD-related surgery.

We also observed some potential heterogeneity in effects with a stronger effect among women and older patients, although neither interaction met statistical significance. The gender difference could relate to genetic susceptibility to depression among women including estrogen receptor polymorphisms, impact of fluctuating hormone levels, and differences in coping. Older patients tend to have greater co-morbidity, an increased risk of depression, and lower reserve with respect to changes in their health status and its impact on functioning. The reason behind the difference in effect between CD and UC is unclear. Despite a majority of the risk loci being shared between CD and UC, considerable differences exist in the effect of environmental factors on the two diseases. While most notably observed are the divergent effects of smoking and appendectomy on disease risk, prior work including ours examining the effect of depressive symptoms on disease risk has demonstrated a stronger effect on CD. Whether this is because of different dominant pathways of influence in CD (innate immunity, autophagy) compared to UC (epithelial barrier function) merits further exploration as depressive and psychosocial stress may not have a uniform impact on all components of the immune system.

The second key aspect of our study is the examination of healthcare utilization among the cohort of IBD patients with psychiatric co-morbidity. Adjusting for potential confounders and duration of follow-up, we identified that depression or anxiety is associated with significantly greater rates of all-cause hospitalization and outpatient visits including to gastroenterologists. Also concerning is our finding of the independent effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on undergoing abdominal imaging studies, primarily CT scans. We were not able to ascertain whether the imaging studies obtained were appropriate, but several recent studies have highlighted the high frequency of radiographic studies in CD patients41–43. Thus, it is important for treating physicians to recognize underlying psychiatric co-morbidity could be a potential risk factor for multiple radiologic studies, to practice judicious use of imaging studies and use alternate imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies wherever indicated and possible in such patients. While the excess healthcare utilization associated with depression or anxiety has not been specifically examined in the context of IBD, our findings are consistent with studies in the primary care population44 and other chronic diseases where depression and anxiety are associated with increased healthcare utilization23, 24, 28. Specifically, the higher odds ratios we identified for all-cause hospitalization (compared to primary IBD-related hospitalizations), and overall outpatient visits (compared to visits to gastroenterologists) highlights that in addition to its effect on IBD itself, the impact of depression or anxiety on overall healthcare utilization may be greater for non-IBD related measures as has been demonstrated previously for asthma26.

In addition to its effect on healthcare utilization, we also found that psychiatric comorbidity was associated with an increase in use of corticosteroids in both CD and UC, and immunomodulator use in UC. There are a few potential reasons for this association. First, it is possible that, as noted by prior studies, co-existing anxiety or depression may be associated with increased symptoms which may lead to initiation of systemic steroids. Secondly, use of systemic steroids itself is associated with significant neuropsychiatric side effects – euphoria and mania in the acute setting, and depression with long-term use45–47. As the timing of initiation or cessation of such episodic therapy is often incompletely captured in the EMR, we were not able to establish causal association between medication use and psychiatric co-morbidity, but this association is consistent with that identified with other disease specific measures such as office visits and need for surgery.

Our study has several implications. To our knowledge, ours is the first study examining the effect of co-existing depression or anxiety on IBD-related surgery over a prolonged follow-up. By excluding those who had first reported a diagnosis of psychiatric co-morbidity following surgery or hospitalization, and using propensity score adjustment, we minimized possibility of reverse causality or residual confounding by disease severity, and increased the robustness of our findings. While the strength of association remains fairly modest when adjusted for other potential confounders, depression or anxiety forms a potentially modifiable risk factor for subsequent disease relapses or surgical morbidity. In addition, both depression and anxiety are also associated with impairment in disease-specific as well as overall health related quality of life and psychosocial functioning. Thus, our results, in conjunction with prior studies in the literature, suggest a potential need for routine screening for psychiatric co-morbidity in IBD patients. In addition, there is continued need for research on interventions addressing depression and anxiety in IBD patients as the literature so far has been limited and conflicting22, 48, 49. Such interventions may improve mood and health-related quality of life as well as natural history of disease and IBD-related healthcare costs. There is also need for continued basic research on identification of the mechanisms how stress and psychologic factors influence IBD course, and whether there are genetic, environmental, or psycho-behavioral risk factors that increase susceptibility to the effect of stress.

There are a few limitations of our study. We relied on the use of administrative codes to identify the presence and date of diagnosis of depression and anxiety in our IBD cohort. Thus, there is the possibility of misclassification. However, this would likely bias the results towards the null, and would result in the true effect being larger than in our study. We also validated the accuracy of these codes in our data. However, we acknowledge that there may exist differences between studies that rely on established diagnoses compared to those using a structured psychiatric interview for cross-sectional assessment. We also accounted for the fact that the diagnosis code of depression or anxiety may be secondary to increased frequency of healthcare utilization by adjusting for the density of such utilization in our analysis and found no difference in our odds ratios. We acknowledge the possibility of residual confounding by disease severity or unmeasured confounders as exists in all observational studies. To minimize the effect of this, we used propensity score adjustment. However, propensity scores incorporate only known confounders and fail to completely account for unknown confounders including psycho-socioeconomic variables. Given the retrospective design of the study, we also did not have detailed information regarding the severity of psychological co-morbidity or the impact of treatment for anxiety or depression on healthcare utilization and need for surgery in IBD. In particular, the use of antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications is inadequately captured within our electronic medical record system; thus the impact of such interventions on disease course merit exploration in future studies. We also did not have prospectively collected disease activity indices, endoscopic or other biomarkers of ongoing inflammation. Finally, because ours are referral institutions, we may not have identified exposures or outcomes that were predominantly documented outside our healthcare system. However, the consistency of our results adjusting for healthcare utilization density (as a measure of comprehensiveness of care within our health system) increases our confidence in our findings. We were also not able to examine the effect of psychiatric co-morbidity on medication nonadherence.

In conclusion, using a large multi-institution cohort of IBD patients, we demonstrate that the presence of depression or anxiety is associated with a modestly increased risk of surgery in patients with CD. We did not identify a similar association in UC patients. In addition, psychiatric co-morbidity was associated with significantly greater disease- and non-disease related healthcare utilization in both CD and UC, suggesting a need for routine screening for depression and anxiety in IBD patients. Further establishment of the effectiveness of interventions to address this component of IBD care is important to improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The study was supported by NIH U54-LM008748. A.N.A is supported by funding from the American Gastroenterological Association and from the US National Institutes of Health (K23 DK097142). K.P.L. is supported by NIH K08 AR060257 and the Katherine Swan Ginsburg Fund. R.M.P. is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01-AR056768, U01-GM092691 and R01-AR059648) and holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. E.W.K is supported by grants from the NIH (K24 AR052403, P60 AR047782, R01 AR049880).

Footnotes

Authorship Statement

Guarantor of the article: Dr. Ananthakrishnan

Specific author contributions:

Guarantor of the article – Ananthakrishnan

Study concept – Ananthakrishnan

Study design – Ananthakrishnan, Cai, Karlson, Liao

Data Collection – Ananthakrishnan, Gainer, Guzman Perez, Cai, Cheng, Savova, Chen, Churchill, Kohane, Shaw, Xia, De Jager, Plenge, Liao, Szolovits, Murphy

Analysis – Ananthakrishnan, Cai, Cheng, Perlis

Preliminary draft of the manuscript – Ananthakrishnan

Approval of final version of the manuscript – Ananthakrishnan, Gainer, Cai, Guzman Perez, Cheng, Savova, Chen, Xia, De Jager, Shaw, Churchill, Karlson, Kohane, Perlis, Plenge, Murphy, Liao

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Loftus EV, Jr, Guerin A, Yu AP, Wu EQ, Yang M, Chao J, Mulani PM. Increased risks of developing anxiety and depression in young patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1670–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105–18. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, Colombel JF, Gendre JP. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ibd.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Pan A, Higuchi LM, ds PS, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Incidence of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis—Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Graff LA, Bernstein CN. Do NSAIDs, antibiotics, infections, or stress trigger flares in IBD? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1298–313. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.15. quiz 1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rampton D. Does stress influence inflammatory bowel disease? The clinical data. Dig Dis. 2009;27 (Suppl 1):76–9. doi: 10.1159/000268124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maunder RG. Evidence that stress contributes to inflammatory bowel disease: evaluation, synthesis, and future directions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:600–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000161919.42878.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. The role of psychological stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13:327–36. doi: 10.1159/000104861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1481–91. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North CS, Alpers DH, Helzer JE, Spitznagel EL, Clouse RE. Do life events or depression exacerbate inflammatory bowel disease? A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:381–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persoons P, Vermeire S, Demyttenaere K, Fischler B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, Pierik M, Hlavaty T, Van Assche G, Noman M, Rutgeerts P. The impact of major depressive disorder on the short- and long-term outcome of Crohn’s disease treatment with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:101–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winrow VR, Mojdehi GM, Ryder SD, Rhodes JM, Blake DR, Rampton DS. Stress proteins in colorectal mucosa. Enhanced expression in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1994–2000. doi: 10.1007/BF01297075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camara RJ, Schoepfer AM, Pittet V, Begre S, von Kanel R. Mood and nonmood components of perceived stress and exacerbation of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2358–65. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghia JE, Blennerhassett P, Deng Y, Verdu EF, Khan WI, Collins SM. Reactivation of inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model of depression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2280–2288. e1–4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mussell M, Bocker U, Nagel N, Singer MV. Predictors of disease-related concerns and other aspects of health-related quality of life in outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1273–80. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200412000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guthrie E, Jackson J, Shaffer J, Thompson D, Tomenson B, Creed F. Psychological disorder and severity of inflammatory bowel disease predict health-related quality of life in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1994–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bitton A, Dobkin PL, Edwardes MD, Sewitch MJ, Meddings JB, Rawal S, Cohen A, Vermeire S, Dufresne L, Franchimont D, Wild GE. Predicting relapse in Crohn’s disease: a biopsychosocial model. Gut. 2008;57:1386–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.134817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodhand JR, Wahed M, Rampton DS. Management of stress in inflammatory bowel disease: a therapeutic option? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:661–79. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowles SR, Wilson JL, Connell WR, Kamm MA. Preliminary examination of the relations between disease activity, illness perceptions, coping strategies, and psychological morbidity in Crohn’s disease guided by the common sense model of illness. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2551–7. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Andreoli A, Luzi C, Arca M, Berto E, Milite G, Marcheggiano A. Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1213–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deter HC, von Wietersheim J, Jantschek G, Burgdorf F, Blum B, Keller W. High-utilizing Crohn’s disease patients under psychosomatic therapy. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodhand JR, Greig FI, Koodun Y, McDermott A, Wahed M, Langmead L, Rampton DS. Do antidepressants influence the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease? A retrospective case-matched observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1232–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson TJ, Basu S, Pisani BA, Avery EF, Mendez JC, Calvin JE, Jr, Powell LH. Depression predicts repeated heart failure hospitalizations. J Card Fail. 2012;18:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng TP, Niti M, Fones C, Yap KB, Tan WC. Co-morbid association of depression and COPD: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2009;103:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, Cao Z, Ong KC, Eng P. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson LP, Russo JE, Lozano P, McCauley E, Katon W. The effect of comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders on health care utilization and costs among adolescents with asthma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:352–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu W, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Lin Y, Yang T, Platt RW, Wang C, Bourbeau J. Independent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:913–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-619OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ananthakrishnan AN, Cai T, Savova G, Chen P, Guzman Perez R, Gainer VS, Murphy SN, Szolovits P, Xia Z, Shaw S, Churchill S, Karlson EW, Kohane I, Plenge RM, Liao KP. Improving Case Definition of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Electronic Medical Records Using Natural Language Processing: A Novel Informatics Approach. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828133fd. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro VM, Gallagher PJ, Clements CC, Murphy SN, Gainer VS, Fava M, Weilburg JB, Churchill SE, Kohane IS, Iosifescu DV, Smoller JW, Perlis RH. Incident user cohort study of risk for gastrointestinal bleed and stroke in individuals with major depressive disorder treated with antidepressants. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000544. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryant RV, van Langenberg DR, Holtmann GJ, Andrews JM. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: impact on quality of life and psychological status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:916–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrokhyar F, Marshall JK, Easterbrook B, Irvine EJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and mood disorders in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and impact on health. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:38–46. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195391.49762.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piche T, Ducrotte P, Sabate JM, Coffin B, Zerbib F, Dapoigny M, Hua M, Marine-Barjoan E, Dainese R, Hebuterne X. Impact of functional bowel symptoms on quality of life and fatigue in quiescent Crohn disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:626–e174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker JR, Ediger JP, Graff LA, Greenfeld JM, Clara I, Lix L, Rawsthorne P, Miller N, Rogala L, McPhail CM, Bernstein CN. The Manitoba IBD cohort study: a population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1989–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mawdsley JE, Macey MG, Feakins RM, Langmead L, Rampton DS. The effect of acute psychologic stress on systemic and rectal mucosal measures of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:410–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rampton DS. The influence of stress on the development and severity of immune-mediated diseases. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;88:43–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mardini HE, Kip KE, Wilson JW. Crohn’s disease: a two-year prospective study of the association between psychological distress and disease activity. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:492–7. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000020509.23162.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mittermaier C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Oefferlbauer-Ernst A, Miehsler W, Beier M, Tillinger W, Gangl A, Moser G. Impact of depressive mood on relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective 18-month follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:79–84. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106907.24881.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Holtmann GJ, Andrews JM. Does psychological status influence clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other chronic gastroenterological diseases: an observational cohort prospective study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levi Z, Fraser E, Krongrad R, Hazazi R, benjaminov O, meyerovitch J, Tal OB, Choen A, Niv Y, Fraser G. Factors associated with radiation exposure in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1128–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer L, Herfarth H, Porter CQ, Fordham LA, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Diagnostic ionizing radiation exposure in a population-based sample of children with inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2816–23. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peloquin JM, Pardi DS, Sandborn WJ, Fletcher JG, McCollough CH, Schueler BA, Kofler JA, Enders FT, Achenbach SJ, Loftus EV., Jr Diagnostic ionizing radiation exposure in a population-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2015–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01920.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, Unutzer J. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:897–903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dubovsky AN, Arvikar S, Stern TA, Axelrod L. The neuropsychiatric complications of glucocorticoid use: steroid psychosis revisited. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patten SB, Neutel CI. Corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects: incidence, diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22:111–22. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200022020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1361–7. doi: 10.4065/81.10.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deter HC, Keller W, von Wietersheim J, Jantschek G, Duchmann R, Zeitz M. Psychological treatment may reduce the need for healthcare in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:745–52. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmer A, Preiss JC, Motschall E, Rucker G, Jantschek G, Moser G. Psychological interventions for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD006913. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006913.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.