Abstract

Purpose

Diabetic retinopathy is a leading cause of blindness due to a progressive damage of the retina by neovascularization and other related ocular complications. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the development of diabetic retinopathy is not well understood. An increase in estrogen levels during puberty is associated with an accelerated development of diabetic retinopathy. Previously, we have introduced 17β-estradiol (E2) to rhesus retinal capillary endothelial cells (RhRECs) in culture and observed a dose- and time-dependent increase in the number of viable cells. The purpose of this present study was to investigate the molecular signaling pathway associated with this estrogen-induced proliferation of RhRECs.

Methods

Estrogen receptor (ER) ERα and ERβ mRNA expression, and protein synthesis were measured at 0, 3, 6, and 12 h using nested polymerase chain reaction and Western blots. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway inhibitors were introduced into culture media to study their effects on E2-induced cell proliferation and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) synthesis. The levels of PEDF in the conditioned media were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

Exogenous E2 induced a significant increase in the expression of ERβ along with an increase in the number of viable RhRECs. Cotreatment of E2 with PI3K and MAPK inhibitors significantly reduced the E2-induced effect on cell proliferation and PEDF production in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusion

Results from the present study suggest that an E2-induced increase in the proliferation of RhRECs may be mediated by the action of ERβ. Both PI3K and MAPK signaling pathways are involved in this E2-induced cell proliferation, which may follow changes in PEDF levels controlled by these pathways. Further studies will provide additional details on the interaction between these pathways to control changes in PEDF levels and cell proliferation.

Introduction

Proliferation of the retinal microvascular endothelium is an integral component in the development of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), a major cause of blindness worldwide.1 Major stimuli for the development of PDR are hypoxia and the overproduction of growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).2 Clinical intervention using laser photocoagulation may reduce this PDR-associated angiogenesis, but in the process creates its own set of problems. Also, VEGF blockers may temporarily halt the development of angiogenesis, but do not address the underlying hypoxia. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) has also been shown to be a potent cytokine, which inhibits angiogenesis in the mammalian eye.3 PEDF levels have been found to be positively linked to retinal oxygen concentrations and are inversely related to VEGF concentrations in a balance controlling angiogenesis.4

Sex hormones, such as estrogen, have long been investigated as a contributing factor in diseases, such as breast cancer and retinopathy.5–8 Estrogens are steroid hormones that regulate growth, differentiation, and function diversely in tissues both within and outside the reproductive system. Estrogen can regulate gene expression through genomic or nongenomic pathways.9 The effects of estrogen are mediated by specific nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor (ER)α and β, that act as hormone-inducible transcription factors.10,11 ERs are highly conserved between ERα and ERβ, with >95% homology for the DNA-binding domain and ≈50% homology for the ligand-binding domain. Less homology is observed for the trans-activational domain between ERα and ERβ. Wu et al. showed a 97% sequence homology between the Rhesus monkey ERβ and human ERβ cDNA.12 Nongenomic effects of estrogen are also mediated by ERs, but they occur relatively rapidly and do not involve alterations in gene expression. ERs may also associate with plasma membrane by attachment to caveolin-1 and form complexes with G-proteins, striatin, tyrosine receptor kinases, and nontyrosine receptor kinases.13,14 Through striatin, some of these membrane-bound ERs may lead to increased levels of Ca2+ and nitric oxide.15 The receptor tyrosine kinase signals are sent to the nucleus through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K/AKT) pathway.16 Nontranscriptional signaling mechanisms play a primary role in generating steroid effects on endothelial cells.9 MAPK/ER cross talk enhances ER-mediated signaling and accelerates estrogen-dependent tumor growth without diminishing sensitivity to the inhibitory effects of antiestrogens in MCF-7 cells.17 ERs are an important upstream regulator of PEDF gene expression in human ovarian surface epithelial cells and addition of an ER blocker reduces PEDF expression.18

In a previous study, we reported that exogenously added estrogen (E2) induced a significant increase in the number of viable rhesus retinal capillary endothelial cells (RhRECs) in culture.19 In addition, this E2-induced cell proliferation was associated with a significantly reduced level of PEDF in the conditioned media. LY294002 was selected in this study because Guo et al. reported that this inhibitor blocked the activating AKT in a dose-dependent manner and that 50 μM of LY294002 completely blocked the activation of AKT induced by E2.20 SB202190 is a specific inhibitor of the MAPK pathway and it was selected in this study to inhibit E2-induced cell proliferation. Using these 2 signaling pathway inhibitors, we provide experimental evidence to identify the involvement of an ER and 2 signaling pathways, which may be responsible for E2-induced changes in cell proliferation and PEDF synthesis.

Methods

Culture of retinal capillary endothelial cells

RhRECs were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC no. CRL-1780). These RhRECs (Macaca mulatta) were spontaneously transformed at an early passage and were received at passage 33. All experiments were done between passages 36 and 40. Once received from ATCC, the RhRECs were grown in a minimum essential medium alpha (Gibco, no. 1061029) without phenol red, containing 10% charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum (to remove hormones) (Gibco, no. 12676-011) and 0.5% antibiotic (ATCC, no. 30-2300), at a final concentration of 50 IU/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. They were incubated with 5% CO2 and at 37°C.

17β-Estradiol (E2) (CalBiochem; no. 3301), the PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) (Cell Signaling; no. 9901), and the MAPK inhibitor (SB202190) (Sigma; no. S7067) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). DMSO by itself did not have any effect on cell proliferation or PEDF levels (data not shown).

PEDF determination

Quantitative sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed and the cell media was used to quantify PEDF (Millipore), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Dynex plate reader and was analyzed using Revelation 4.25 software. Concentrations of PEDF were quantified by comparing absorbance with their respective standard curves.

Estrogen-induced ERα and ERβ mRNA expression in RhREC

RhRECs were introduced at a seeding density of 20,000 cells/mL and allowed to proliferate for 24 h and treated with or without E2 for 3, 6, and 12 h. Total RNA was isolated from RhRECs at 0, 3, 6, and 12 h, treated with 0.0 nM or 1.0 nM E2 in cell media. Following incubation, cells were washed with a 1×Hank's balanced salt solution and total RNA was extracted using 1 mL of Trizol® (Invitrogen, no. 15596-026). Five hundred nanograms of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, no. N8080234). Five microliters of cDNA template was amplified with designed primers using RedTaq PCR (Sigma, no. R2523).

ER sequence information for both α and β isoforms were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). M. mullata's ERα was a predicted sequence with 2 splice variants. ERα var-1 was a 595aa protein coded by 2,445 bp (XM_001097228). ERα var-2 was also 595aa protein coded by 7,566 bp (XM_002803858). ERβ var-1 was a 530aa protein coded by 1,796 bp (XM_001101433). ERβ var-2 was 502aa protein coded by 2,462 bp (XM_002805066). Three sets of primers were generated for performing nested polymerase chain reaction. As a loading control, M. mullata's β-actin housekeeping gene was also amplified.

ERα

Sense primer 1: CAG CAG CAA GCC CGC CGT GTA CAA CTA, Anti-sense primer 1: GTC AAA TCC ACA AAG CCT GGC ACC CTC, Sense primer 2: CCG CCG TGT ACA ACT ACC CCG AGG, Anti-sense primer 2: GCA CCC TCT TTG CCC AGT TGA TCA TGT G.

ERβ

Sense primer 1: TGA TGA ATT ACA GCA GTC CCA GCA ATG TCA C, Anti-sense primer 1: AAC CTT GAA GTA GTT GCC AGG AGC ATG TCA, Sense primer 2: CCA GCA ATG TCA CTA ACT TGG AAG GTG GG, Anti-sense primer 2: GTTGCCAGGAGCATGTCAAAG ATT TCC AGA AT.

β-actin

Sense primer: ACCCCAGCCATGTACGTGGCC ATCC, Anti-sense primer: GCCTCAGGGCAGCGGAACCG CTCA.

E2-induced ERα and ERβ receptor protein expression and synthesis

RhRECs were cultured at a seeding density of 20,000 cells/mL and allowed to proliferate with 1.0 or 0 nM E2 for 3, 6, and 12 h. Cells were lysed and total protein was collected using 200 μL of RIPA buffer. Total protein was resolved on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotting was done with rabbit anti-ERα (polyclonal antibody 1:500) and rabbit anti-ERβ (monoclonal antibody 1:1,000). Immunodetection was done with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine. Band intensity was measured using Adobe Photoshop CS4. Relative intensity in Fig. 1C was determined from the ratio between ERβ and β-actin at different treatment times. These ratios were then normalized to the ratio between ERβ and β-actin expression at time zero.

FIG. 1.

E2-induced ER expression and synthesis in RhRECs. (A) The agarose gel image of expressed ERα and ERβ mRNA are shown. ERβ mRNA was highly expressed after estrogen treatment for 3 and 6 h. (B) Quantification of gel images is represented by fold change of image intensity relative to β-actin expression (baseline). (C) Fifty micrograms of total protein from RhREC lysate collected at 0, 3, 6, and 12 h of 0.0 or 1.0 nM E2 were resolved on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed with antibodies to ERα and ERβ. No signal for ERα was observed (blot not shown). The relative image intensity for ERβ protein (ERβ/β-actin) was determined using Adobe Photoshop CS4. ER, estrogen receptor; RhRECs, rhesus retinal capillary endothelial cells.

LY294002 inhibition of E2-induced cell proliferation and PEDF release

RhRECs were cultured at a seeding density of 20,000 cells/mL and allowed to proliferate for 24 h in each of the treatment groups with 0.1, 1.0, or 10.0 nM LY294002 along with 1.0 nM E2 in the cell media. Cells were counted in a Neubauer hemocytometer with the trypan blue exclusion method to determine the total number of viable cells. Conditioned media were collected for ELISA determination of PEDF levels.

SB202190 inhibition of E2-induced cell proliferation and PEDF release

RhRECs were cultured at a seeding density of 20,000 cells/mL and allowed to proliferate for 24 h in each of the treatment groups with 0.1, 1.0, or 10.0 nM SB202190 along with 1.0 nM E2 in the cell media. Cells were counted in a Neubauer hemocytometer with the Trypan blue exclusion method to determine the total number of viable cells. Conditioned media were collected for ELISA determination of PEDF levels.

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and one-way analysis of variance. In the figures, we use *, **, and *** to indicate the level of significance (P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001). All experiments were repeated a minimum of 3 times with triplicates.

Results

E2-induced ER expression and synthesis in RhRECs

The agarose gel images show that ERα mRNA was expressed by cells treated with 1.0 nM E2 (Fig. 1A), but the protein was not detected by Western blots (data not shown). ERβ mRNA was highly expressed at the 3- and 6-h time point with E2 treatment (Fig. 1A, B). Western blots show that the ERβ protein was also present in cell lysates at the corresponding time points (Fig. 1C). Quantification of blot images showed that ERβ expression levels were significantly higher in cells treated with estrogen compared with those without estrogen at the 3- and 6-h time point (Fig. 1B, C).

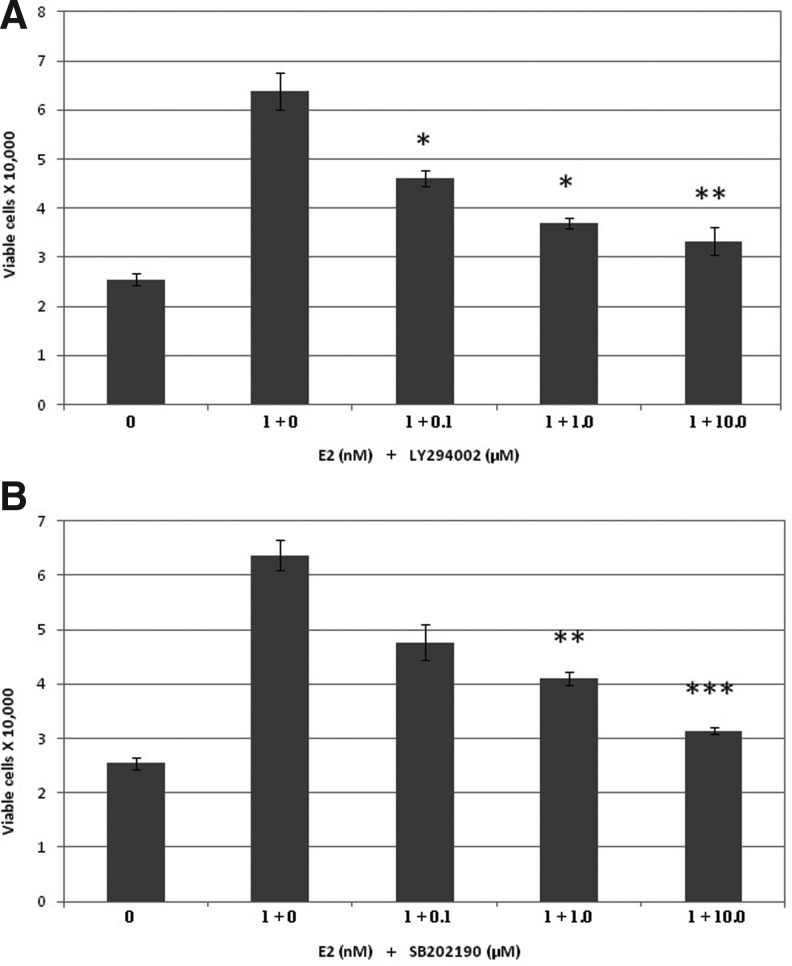

LY294002 and SB202190 inhibition of E2-induced RhREC proliferation

The addition of exogenous E2 induced a significant increase in the number of viable RhRECs (Fig. 2A). This E2-induced cell proliferation was significantly reduced by the cotreatment of E2 and LY294002. The cell number was reduced by 28% when cells were grown in 0.1 μM LY294002 and 1.0 nM E2, 42% when cells were grown in 1.0 μM LY294002 and 1.0 nM E2, and 48% when cells were grown in 10.0 μM LY294002 and 1.0 nM E2 compared to those grown in 1.0 nM E2 alone (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

LY294002 and SB202190 inhibition of E2-induced cell proliferation. RhRECs were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells/mL and cells were treated with 0.0 and 1.0 nM E2 and cotreated with 1.0 nM E2 and 0.1, 1.0, or 10.0 μM LY294002, or SB202190 for 24 h. (A) E2-enhanced cell proliferation was significantly inhibited by each increasing concentration of LY294002: 0.1 μM LY294002 (P<0.05), 1.0 μM LY294002 (P<0.05), and 10.0 μM LY294002 (P<0.01). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for dose–response effect among 3 concentrations of LY294002, F (3, 4)=77.16, P=0.00053. Inhibition of E2-induced proliferation was significant across the 3 concentrations of LY294002. (B) E2-enhanced cell proliferation was significantly inhibited by each increasing concentration of SB202190: 1.0 μM SB202190 (P<0.01) and 10.0 μM SB202190 (P<0.001). A one-way ANOVA was used to test for dose–response effect among 3 concentrations of SB202190, F (3, 4)=36.6, P=0.00228. Inhibition of E2-induced proliferation was significant across the 3 concentrations of SB202190. *, **, and *** to indicate the level of significance (P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001).

The addition of exogenous E2 induced a significant increase in the number of viable RhRECs (Fig. 2B). This E2-induced cell proliferation was significantly reduced by the cotreatment of E2 and SB202190. The cell number was reduced by 25% when cells were grown in 0.1 μM SB202190 and 1.0 nM E2, 36% when cells were grown in 1.0 μM SB202190 and 1.0 nM E2, and 51% when cells were grown in 10.0 μM SB202190 and 1.0 nM E2, compared to those grown in 1.0 nM E2 alone (Fig. 2B).

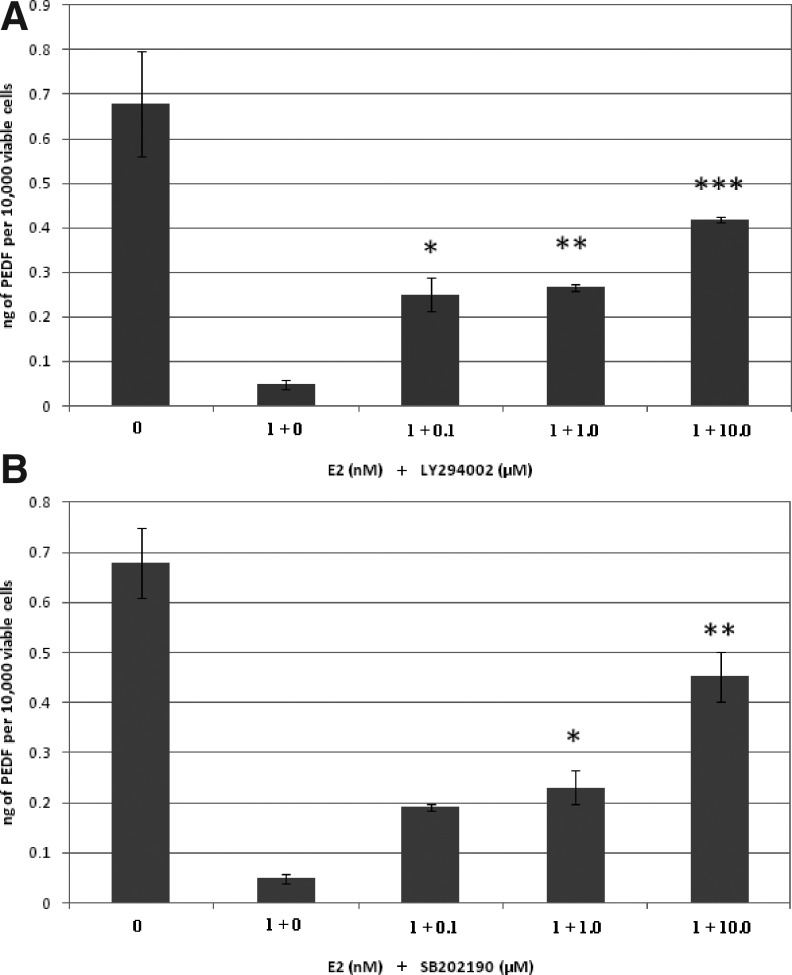

Effect of LY294002 and SB202190 on E2-induced decrease in PEDF

Exogenously added E2 significantly reduced the level of PEDF in the RhREC culture media (Fig. 3A). Cotreatment of E2 and LY294002 significantly increased PEDF levels by 5-fold when cells were grown in 0.1 μM LY294002+1.0 nM E2 and 1.0 μM LY294002+1.0 nM E2, and by 10-fold when cells were grown in 10.0 μM LY294002+1.0 nM E2, compared to those grown in 1.0 nM E2 alone (Fig. 3A). PEDF levels were increased by 4-fold when RhRECs were grown in growth media containing 0.1 μM SB202190+1.0 nM E2 and 1.0 μM SB202190+1.0 nM E2, and by 9-fold when cells were grown in 10.0 μM SB202190+1.0 nM E2, compared to those grown in 1.0 nM E2 alone (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Effect of LY294002 and SB202190 on E2-induced changes in pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) levels in cell media. RhRECs were grown for 24 h in a medium containing either 0.0 or 1.0 nM E2 alone or cotreated by 1.0 nM E2 and 0.1, 1.0, or 10.0 μM LY294002 (A) or SB202190 (B). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed on the cell medium to quantify PEDF. (A) PEDF levels were significantly greater in the 1.0 nM E2 group cotreated with 10.0 μM LY294002 group compared to the 1.0 nM E2 alone group (P<0.001). A one-way ANOVA was used to test for dose–response effect among 3 concentrations of LY294002. Inhibitor effect was significant across the 3 concentrations, F (3, 4)=30.46, P=0.00325. (B) PEDF levels were significantly increased in the 1.0 nM E2 cotreated with 10.0 μM SB202190 compared to the 1.0 nM E2 alone group (P<0.01). A one-way ANOVA was used to test for dose–response effect among 3 concentrations of SB202190. Inhibitor effect was significant across the 3 concentrations, F (3, 4)=8.72, P=0.0314. Mean±standard error (n=3) from 1 experiment is shown. Data are normalized based on the number of viable cells in the assay. PEDF concentrations/10,000 cells were determined by dividing the PEDF concentration in each individual well by the corresponding cell number to calculate PEDF concentration/10,000 viable cells. *, **, and *** to indicate the level of significance (P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we have observed that RhRECs expressed ERβ, but not the ERα protein. This is in agreement with Critchley et al.'s previous work with ER expression in the vascular endothelium of human and nonhuman primates.21

PEDF and VEGF are known to influence retinal angiogenesis.22 Their inverse relationship has been shown in many other cell types.23,24 In a previous report, we have already published data showing that E2 decreases the expression of PEDF in RhREC.19 In the present study, we provide strong experimental evidence to show that both PI3K and MAPK pathway inhibitors effectively blocked the action of E2-induced cell proliferation and inhibition of PEDF expression. This suggests both signaling pathways may be involved in the control of cell proliferation and PEDF synthesis. In a different study, Guo et al. reported that the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, blocked the activating AKT in a dose-dependent manner and 50 μM of LY294002 completely blocked the activation of AKT induced by E2.20 It is possible that E2, acting through ERβ, also activated membrane-bound receptor kinases leading to downstream signaling involving PI3K/AKT or MAPK.25,26 In fact our data suggest the E2, acts through ERβ, to activate membrane receptor kinases, leading to downstream signaling involving P13K/AKT or MAPK influencing cell proliferation and PEDF. Our results also show that estrogen increased the level of ERβ mRNA (Fig. 1A, B) and protein (Fig. 1C). It is possible that E2, acting through ERβ, also exerts its effects on proliferation and PEDF via transcriptional regulation in the nucleus, via the genomic pathway of estrogen action at target cells. Additional experiments will be needed to further elucidate the exact role of each of these 2 signaling pathways and the role of ERs on E2-induced PEDF synthesis and cell proliferation in RhRECs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jilani Chaudry, Dr. Ratna Vadlamudi, Dr. Willam Ramos, and Dr. Eileen Kotchan for their help in completion of this work. We also thank The Kronkosky Charitable Foundation, The San Antonio Neuroscience Alliance, The San Antonio Area Foundation, STTM, and CRSGP programs for their generous support of our work. This project was supported by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5G12RR013646-12) and the National Institutes of Minority Health and Health Disparities (G12MD007591) from the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Yan Q. Vernon R.B. Hendrickson A.E. Sage E.H. Primary culture and characterization of microvascular endothelial cells from Macaca monkey retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996;37:2185–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elayappan B. Ravinarayannan H. Sardar Pasha S.P. Lee K.J. Gurunathan S. PEDF inhibits VEGF- and EPO-induced angiogenesis in retinal endothelial cells through interruption of PI3K/Akt phosphorylation. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takenaka K. Yamagishi S. Jinnouchi Y. Nakamura K. Matsui T. Imaizumi T. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF)-induced apoptosis and inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in MG63 human osteosarcoma cells. Life Sci. 2005;77:3231–3241. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao G. Li Y. Zhang D. Gee S. Crosson C. Ma J. Unbalanced expression of VEGF and PEDF in ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. FEBS Lett. 2001;489:270–276. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Love R.R. Philips J. Oophorectomy for breast cancer: history revisited. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1433–1434. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beatson G.T. On the treatment of inoperable cases of carcinoma of the mamma: suggestions for a new method of treatment with illustrative cases. Lancet. 1896;1896:104–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacassagne A. Hormonal pathogenesis of adenocarcinoma of the breast. Am. J. Cancer. 1936;27:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grigsby J.G. Allen D.M. Culbert R., et al. The Role of Sex Hormones in Diabetic Retinopathy. Rijeka: InTech; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simoncini T. Mannella P. Fornari L. Caruso A. Varone G. Genazzani A.R. Genomic and non-genomic effects of estrogens on endothelial cells. Steroids. 2004;69:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller J.H., Jr. Gates R.E. Ong D.E. King L.E., Jr. A miniature molecular-sieving column assay for cytoplasmic vitamin A-binding proteins. Anal. Biochem. 1984;139:104–114. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar V. Green S. Stack G. Berry M. Jin J.R. Chambon P. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell. 1987;51:941–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu W.X. Ma X.H. Smith G.C. Nathanielsz P.W. Differential distribution of ERalpha and ERbeta mRNA in intrauterine tissues of the pregnant rhesus monkey. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C190–C198. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.1.C190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin E.R. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zivadinovic D. Gametchu B. Watson C.S. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha levels in MCF-7 breast cancer cells predict cAMP and proliferation responses. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R101–R112. doi: 10.1186/bcr958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Q. Pallas D.C. Surks H.K. Baur W.E. Mendelsohn M.E. Karas R.H. Striatin assembles a membrane signaling complex necessary for rapid, nongenomic activation of endothelial NO synthase by estrogen receptor alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:17126–17131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407492101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato S. Endoh H. Masuhiro Y., et al. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 1995;270:1491–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atanaskova N. Keshamouni V.G. Krueger J.S. Schwartz J.A. Miller F. Reddy K.B. MAP kinase/estrogen receptor cross-talk enhances estrogen-mediated signaling and tumor growth but does not confer tamoxifen resistance. Oncogene. 2002;21:4000–4008. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung L.W. Au S.C. Cheung A.N., et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor is estrogen sensitive and inhibits the growth of human ovarian cancer and ovarian surface epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4179–4191. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grigsby J.G. Parvathaneni K. Almanza M.A., et al. Effects of tamoxifen versus raloxifene on retinal capillary endothelial cell proliferation. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;27:225–233. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo R.X. Wei L.H. Tu Z., et al. 17 Beta-estradiol activates PI3K/Akt signaling pathway by estrogen receptor (ER)-dependent and ER-independent mechanisms in endometrial cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. 2006;99:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Critchley H.O.D. Brenner R.M. Henderson T.A., et al. Estrogen receptor beta, but not estrogen receptor alpha, is present in the vascular endothelium of the human and nonhuman primate endometrium. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2001;86:1370–1378. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noma H. Funatsu H. Mimura T. Harino S. Eguchi S. Hori S. Pigment epithelium-derived factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in branch retinal vein occlusion with macular edema. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010;248:1559–1565. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L.W. Zhang J.X. Zeng L., et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy with intramuscular injections of plasmid DNA enhances the survival of random pattern flaps in a rat model. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2005;58:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan M. Yam H.F. Su B., et al. Loss of pigment epithelium derived factor expression in glioma progression. J. Clin. Pathol. 2003;56:277–282. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.4.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bratton M.R. Duong B.N. Elliott S., et al. Regulation of ERalpha-mediated transcription of Bcl-2 by PI3K-AKT crosstalk: implications for breast cancer cell survival. Int. J. Oncol. 2010;37:541–550. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiff R. Massarweh S.A. Shou J. Bharwani L. Mohsin S.K. Osborne C.K. Cross-talk between estrogen receptor and growth factor pathways as a molecular target for overcoming endocrine resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10(1 Pt 2):331S–336S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-031212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]