Summary

Gating of the muscle-type acetylcholine receptor (AChR) channel depends on communication between the ACh-binding site and the remote ion channel. A key region for this communication is located within the structural transition zone between the ligand-binding and pore domains. Here, stemming from β-strand 10 of the binding domain, the invariant αArg209 lodges within the hydrophobic interior of the subunit and is essential for rapid and efficient channel gating. Previous charge-reversal experiments showed that the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating depends strongly on αGlu45, also within this region. Here we determine whether the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating depends on additional anionic or electron-rich residues in this region. Also, to reconcile diverging findings in the literature, we compare the dependence of αArg209 on αGlu45 in AChRs from different species, and compare the full agonist ACh with the weak agonist choline. Our findings reveal that the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating depends on additional nearby electron-rich residues, consistent with both electrostatic and steric contributions. Furthermore, αArg209 and αGlu45 show a strong interdependence in both human and mouse AChRs, whereas the functional consequences of the mutation αE45R depend on the agonist. The emerging picture shows a multifaceted network of interdependent residues that are required for communication between the ligand-binding and pore domains.

Introduction

At the vertebrate motor synapse, nerve-released acetylcholine (ACh) binds to and opens postsynaptic ACh receptor (AChR) channels in the final step of synaptic transmission. The sites to which ACh bind are readily accessible from the synaptic cleft, but the channel gate lies deep within the membrane, remote from the binding sites. An enduring quest is to identify substructures within the AChR that communicate structural changes from the ACh binding site to the channel gate.

Within the AChR pentamer, the two ACh-binding sites are formed at interfaces between each of two α-subunits and either the ε- or δ-subunit (1,2). Structure determination and molecular-dynamics simulations showed that when the agonist binds, the sites contract around and envelop the agonist (3–7). In particular, loop C from the α-subunit changes from an opened-up to a closed-in conformation. When loop C closes in upon the agonist, a key interaction is established between αTyr190 from the first half of loop C and αLys145 of β-strand 7, and a second interaction between αAsp200 from the second half of loop C and αLys145 is maintained in both conformations. Mutagenesis studies showed that both interactions are required to couple agonist binding to channel gating efficiently, and thus they contribute to early steps in signal transduction (8). In support of these findings, rate-equilibrium, free-energy analyses applied to residues at the agonist-binding site showed that the free energy of the channel-opening transition changed in direct proportion with that of the channel-gating equilibrium, suggesting that residues at the binding site are among the first to change their conformation during the transition from a closed- to open-channel state (9).

β-strands 7, 9, and 10 extend from the ligand-binding site to the junction with the pore domain, where they give rise to the Cys loop, β8-β9 loop, and pre-M1 region, respectively. At this junction, these three structures coalesce with the β1-β2 loop from the binding domain and the M2-M3 loop from the pore domain. Within this assembly of interdomain loops, the invariant αArg209 from β-strand 10 forms a salt bridge with the conserved αGlu45 from the β1-β2 loop (Fig. 1). This salt bridge was initially observed in the cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structural model of the Torpedo AChR (10), and subsequently in x-ray structures of the mouse α1 extracellular domain with bound α-bungarotoxin (11) and in the pentameric bacterial ion channel GLIC (12,13). Studies of charge reversal of this salt bridge showed that it contributed to rapid and efficient coupling of agonist binding to channel gating (14). Subsequent studies, however, showed that hydrophobic substitutions for αGlu45 enabled relatively efficient channel gating (15,16), suggesting that the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating may depend on additional structures in this region. In support of this possibility, structural data revealed additional negatively charged residues near αArg209 (10,11), suggesting that one or more of these residues could have compensated for loss of the negative charge following hydrophobic substitutions for αGlu45.

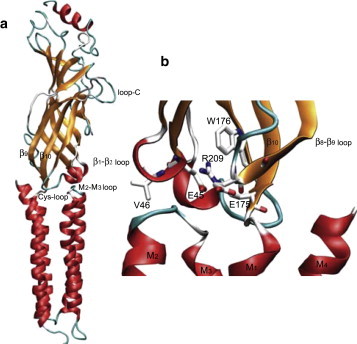

Figure 1.

(a) Structural model of the α-subunit from the Torpedo AChR (PDB code 2BG9). (b) Close-up view of the region between the ligand-binding and pore domains. Key residues are highlighted in stick representation and colored according to electronic charge (blue, positive; red, negative; and gray, neutral).

Herein, we further examine interresidue coupling in the region between the ligand-binding and pore domains of the muscle-type AChR, and test whether the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating depends on additional anionic or electron-rich residues in this region. To evaluate whether differences in the AChR species or type of agonist account for the divergent findings regarding coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45 (14,16), we compare interresidue coupling in human and mouse AChRs, and also compare the full agonist ACh with the weak agonist choline (Ch). Our findings reveal that αArg209 couples to additional nearby electron-rich residues in a manner consistent with both electrostatic and steric contributions, that αArg209 and αGlu45 are strongly coupled in both species of AChR, and that the functional consequences of the mutation αE45R depend on the agonist.

Materials and Methods

Construction of wild-type and mutant AChRs

Human and mouse α, β, δ, and ε-subunit complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were subcloned in the cytomegalovirus-based mammalian expression vector pRBG4 (17) as previously described (18). Site-directed mutations were made using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The presence of each mutation and the absence of unwanted mutations were confirmed by sequencing the entire cDNA insert.

Mammalian cell expression

All experiments were performed using the BOSC 23 cell line (CRL-11270; ATCC, VA), a variant of the HEK 293 cell line. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing fetal bovine serum (10% vol/vol) at 37°C until they reached ∼50–70% confluence. Wild-type (WT) or mutant AChR cDNAs, plus the cDNA encoding green fluorescent protein, were transfected by calcium-phosphate precipitation, with final concentrations of each cDNA of 0.68 μg/ml. Patch-clamp recordings were performed 24–48 h after transfection.

Patch-clamp single-channel recordings

To record single-channel currents, cells transfected with WT or mutant AChR cDNAs were rinsed with and maintained in the following bath solution (in mM): KCl 142, NaCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.7, and HEPES 10 (pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). The same solution was used to fill patch pipettes. The agonists ACh and Ch (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were stored as 100 mM stocks in bath solution at −80°C. Glass micropipettes (type 7052; King Precision Glass, Claremont, CA) were coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning Co., Elizabethtown, KY.) and heat polished to yield resistances of 5–8 MΩ. Single-channel currents were recorded in the cell-attached configuration using the Axopatch 200B (Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA) at a holding potential of −70 mV in experiments in which ACh was the agonist, and −100 mV in experiments in which Ch was the agonist (the greater potential used in recordings with Ch as the agonist was chosen to enable comparison with previous studies using Ch (16)). The temperature was 22°C. Data were collected from two to four different patches for each agonist concentration. Recordings were accepted only if channel activity was low enough to allow identification of activation episodes resulting from a single AChR channel. The current signal was low-pass filtered at 100 kHz and recorded to hard disk at 500 kHz using the program Acquire (Bruxton, Seattle, WA).

Single-channel kinetic analysis

Single-channel kinetic analyses were performed as previously described (19). Briefly, the digitized current signals were analyzed using a 10-kHz digital Gaussian filter, interpolated using a cubic spline function, and then detected using the half-amplitude threshold criterion with correction of the dwell times at threshold for the effects of the Gaussian filter (20). Given these parameters, the minimum detectable open or closed interval was 18 μs. Open- and closed-time histograms were fitted by the sum of exponentials by maximum likelihood using the program TACFit (Bruxton). Openings corresponding to a single receptor channel were identified by assigning a critical closed time, defined as the point of intersection of the closed-time component that depended on agonist concentration with the succeeding concentration-independent component (18), presumably due to desensitization. Clusters of events with five or more openings and mean open probabilities and mean closed times within 2 standard deviations of the respective means were accepted for further analysis; >90% of clusters met these criteria. For the αR209Q mutant in human and mouse AChRs, all openings, except for single isolated openings, were accepted for analysis. A dead time of 22 μs was imposed on all data sets prior to fitting. Kinetic fitting according to Scheme 1 (see results) was conducted simultaneously for data obtained across a range of agonist concentrations (termed global analysis) using MIL software (Qub suite, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY), which corrects for missed events, obtains fitted parameters by maximum likelihood, and gives standard errors (SEs) of the fitted parameters (21). For the WT and mutant receptors studied, the global analysis included data from two to four patches for each agonist concentration (see Fig. S1, Fig. S2, Fig. S3, Fig. S4, and Fig. S5 in the Supporting Material for agonist concentrations). For the triple mutant αE45R+αE175L+αW176L, kinetic modes were identified as previously described (8).

Mutant cycle analysis

To detect interresidue energetic coupling and estimate its magnitude, we applied mutant cycle analysis (22) to the channel gating equilibrium constant Θ2 computed from the ratio of apparent channel gating rate constants β2/α2 (19). For each mutant cycle, the interresidue coupling free energy is given by , where R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, and m1 and m2 are the pair of mutations. To compute the SE for ΔΔG, the likelihood surfaces for each fitted β2 or α2 are assumed to be symmetrical about the maximum. The SE of ΔΔG is then computed from the SE for each rate constant (i.e., SE β2,x) as follows:

where .

Results

Previous studies examined energetic coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45 in either the human AChR with ACh as the agonist (14) or the mouse AChR with a combination of ACh and the weak agonist Ch (16). The study with human AChR and ACh indicated a coupling free energy of −3.1 kcal/mol, whereas the study with mouse AChR and a combination of ACh and Ch indicated a coupling free energy of −1.2 kcal/mol. To determine whether differences in the species of AChR could have accounted for this divergence, we recorded single-channel currents from both human and mouse AChRs activated by the same agonist, ACh. To ensure that the data for the two species were comparable, we obtained new recordings for the human WT and mutant AChRs in parallel with those for the mouse AChR. Single-channel currents were elicited by a range of ACh concentrations. The minimum concentration was 3 μM because this was the lowest concentration that produced clearly identifiable clusters of openings from the same AChR channel, a requirement for kinetic fitting, and the maximum concentration was 1 mM because higher concentrations reduced the single-channel current amplitude due to unresolved channel block.

Channel openings and closings, recorded at a bandwidth of 10 kHz, were detected using the half-amplitude threshold criterion, and the resulting global set of open and closed dwell times was analyzed according to the extended del Castillo and Katz scheme:

| Scheme 1 |

In Scheme 1, A is ACh, R is the receptor, k+n is the agonist association rate constant, k−n is the agonist dissociation rate constant, β2 is the channel opening rate constant, α2 is the channel closing rate constant, and k+b and k−b are the channel blocking and unblocking rate constants, respectively. The rate constants k+1 and k−2 are effective rate constants, which in the case of equivalent binding sites are the product of the number of binding sites and the intrinsic rate constant. To facilitate comparison with previous analyses (14), and because it could not be defined for many mutants owing to limited time resolution, we did not include the recently described brief closed state between the A2R and A2O states (23,24). Thus, the fitted channel gating rate and equilibrium constants are apparent rate and equilibrium constants. The implications of a brief pre-open closed state are outlined in the Discussion. In the following sections, the apparent channel gating equilibrium constant, Θ2, given by the ratio β2/α2, is used to compute coupling free energies between pairs of residues subjected to mutations.

For WT human and mouse AChRs at a membrane potential of −70 mV, channel openings elicited by 100 μM ACh were resolved with a good signal/noise ratio at a bandwidth of 10 kHz (Fig. 2 a). The corresponding open- and closed-time histograms are shown along with the fitted probability density functions (PDFs) from Scheme 1. For human (but not mouse) AChRs, an improved fit was obtained with the addition of a singly liganded open state linked to the singly liganded closed state, AR; addition of this state had little effect on the fitted rate constants β2 and α2. The fitted PDFs, generated from simultaneous fitting of all the data from 3 μM to 1 mM ACh, overlay the dwell-time histograms for both mouse and human AChRs (Fig. 2 a and Fig. S1). The fitted rate constants are well defined and yield estimates of Θ2, K2, and Kb that are very similar between human and mouse AChRs (Table 1). Quantitative differences between the two species include detectable singly liganded openings in human but not mouse AChRs, and moderate increases in β2, k−1, and k−2 in mouse AChRs compared human AChRs.

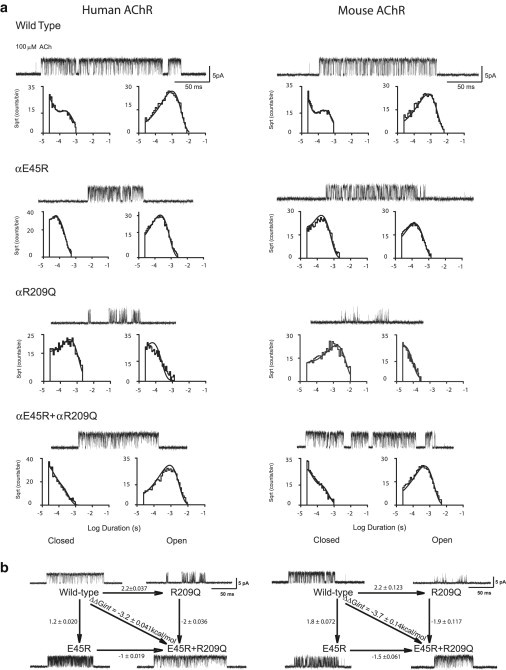

Figure 2.

(a) Kinetics of activation of human and mouse AChRs and the indicated mutants. Currents elicited by 100 μM ACh are shown at a bandwidth of 10 kHz, with channel openings shown as upward deflections. Histograms of closed and open dwell times within identified clusters are shown on logarithmic time axes with PDFs generated from global kinetic fitting overlaid (see Materials and Methods; fitted rate constants are given in Table 1). (b) Energetic coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45. In each two-dimensional mutant cycle, the diagonal line indicates interresidue coupling free energy, and the horizontal and vertical lines indicate free-energy changes due to mutation. SEs of ΔΔG were computed as described in Materials and Methods. The 95% confidence limit, or twice the SE, indicates a coupling energy significantly different from zero.

Table 1.

Kinetics of activation by ACh of human and mouse AChRs expressed in BOSC 23 cells.

| Receptor | k+1 | k−1 | K1 (μM) | k+2 | k−2 | K2 (μM) | β1 | α1 | Θ1 | β2 | α2 | Θ2 | k+b | k−b | Kb (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H Wild type | 350 ± 40 | 3500 ± 440 | 10 | 90 ± 2 | 19000 ± 300 | 211 | 60 ± 6 | 3500 ± 300 | 0.02 | 43000 ± 1100 | 2100 ± 40 | 20 ± 0.67 | 30 ± 3 | 162000 ± 4000 | 5.0 |

| H αE45R | 210 ± 30 | 240 ± 70 | 1.1 | 450 ± 30 | 1300 ± 70 | 2.8 | 240 ± 50 | 9000 ± 110 | 0.03 | 21000 ± 150 | 7400 ± 50 | 2.8 ± 0.028 | 35 ± 2 | 116000 ± 23000 | 3.0 |

| H αR209Q | 270 ± 9 | 1900 ± 90 | 7.0 | 130 ± 4 | 11000 ± 510 | 85 | 20 ± 3 | 3300 ± 310 | 0.006 | 10000 ± 460 | 19000 ± 470 | 0.5 ± 0.027 | 90 ± 20 | 90000 ± 10400 | 0.9 |

| H αE45R αR209Q | 360 ± 6 | 3800 ± 80 | 10 | 180 ± 3 | 7500 ± 140 | 42 | ND | ND | - | 30500 ± 800 | 1900 ± 30 | 16 ± 0.49 | 30 ± 1 | 107000 ± 1100 | 3.5 |

| M Wild-type | 400 ± 70 | 33000 ± 7600 | 82 | 170 ± 14 | 43000 ± 1400 | 250 | ND | ND | - | 77000 ± 6800 | 3700 ± 280 | 21 ± 2.4 | 22 ± 1 | 111000 ± 2500 | 5.0 |

| M αE45R | 400 ± 10 | 900 ± 20 | 2.2 | 200 ± 6 | 1800 ± 40 | 9.0 | 190 ± 20 | 26000 ±3000 | 0.007 | 8000 ± 250 | 8500 ± 53 | 0.9 ± 0.03 | 35 ± 3 | 104000 ± 38000 | 3.0 |

| M αR209Q | 200 ± 6 | 11000 ± 700 | 55 | 100 ± 3 | 23000 ± 1416 | 230 | ND | ND | - | 16000 ± 2600 | 34000 ± 1570 | 0.5 ± 0.08 | 710 ± 40 | 99000 ± 4000 | 0.1 |

| M αE45R αR209Q | 50 ± 3 | 430 ± 30 | 8.6 | 120 ± 4 | 15000 ± 300 | 125 | ND | ND | - | 50000 ± 1300 | 5100 ± 470 | 9.8 ± 0.95 | 20 ± 1 | 96000 ± 2000 | 5.0 |

Values are from global fits of Scheme 1 to data obtained over a range of ACh concentrations (see Figs. S1–S4), with standard errors given (Materials and Methods). Rate constants are in units of μM-1s-1 for association rate constants, and s-1 for all others. ND indicates parameters were not defined. H- indicates human receptor, M- indicates mouse receptor.

For the charge-reversal mutation αE45R, in both human and mouse AChRs, the single-channel current traces show briefer channel openings and fewer brief closings, indicating attenuated channel gating. The fitted PDFs from Scheme 1 superimpose on the closed-and open-time histograms (Fig. 2 a and Fig. S2), and the fitted rate constants reveal that the αE45R mutation decreases Θ2 by 7.5- and 20-fold for the human and mouse AChRs, respectively (Table 1), in general agreement with the 6.4-fold decrease previously observed for human AChR activated by ACh (14). The αE45R mutation also slows the rate constants for ACh dissociation by >10-fold, decreasing K1 and K2, indicating the mutation increases agonist affinity. Thus, in both human and mouse AChRs, substituting Arg for αGlu45 reduces the channel gating equilibrium constant.

For the mutation αR209Q, the single-channel current traces show a greater attenuation of channel gating compared with αE45R (Fig. 2 a). The fitted PDFs from Scheme 1 well describe the closed-time histograms from both species, as well as the open-time histogram for the mouse mutant AChR (Fig. 2 a and Fig. S3). On the other hand, the open-time histogram for the human mutant AChR shows a shortage of events near the peak and an excess of events near the tail, indicating a second doubly liganded open state. An alternative to Scheme 1, though warranted for human αR209Q, was not considered because the frame of reference, the WT AChR, shows a single doubly liganded open state. Notwithstanding the extended open-time distribution for human αR209Q, the fitted rate constants show 40–fold decreases of Θ2 for both mutant human and mouse AChRs (Table 1), which are similar to the decreases previously observed for mutant human and mouse AChRs activated by ACh (14,16). Unlike the mutation αE45R, αR209Q has little effect on the rate constants for ACh dissociation. Thus, in both human and mouse AChRs, substituting Gln for αArg209 markedly reduces the channel gating equilibrium constant.

Given that αArg209 and αGlu45 are near each other in the available structures, we combined mutations of both residues into a single α-subunit to determine whether the functional consequences of the single mutations change when the second residue is subjected to mutation. For the double-mutant human and mouse AChRs, the single-channel current traces show strikingly enhanced channel gating compared with either single mutant, approaching that for the corresponding WT AChR (Fig. 2 a). The fitted PDFs from Scheme 1 conform closely to the closed- and open-dwell-time histograms for the double-mutant AChRs from both species (Fig. 2 a and Fig. S4), and the fitted rate constants confirm that Θ2 increases compared with those for the single-mutant AChRs, approaching Θ2 for the corresponding WT AChR (Table 1). Thus, combining the mutations αR209Q and αE45R increases channel gating efficiency compared with the single mutant human and mouse AChRs. These findings indicate that the large decrease in channel gating caused by the mutation αR209Q depends on αGlu45, confirming previous observations (14).

Double-mutant-cycle analysis is a powerful means to quantify residue interdependence in proteins (22,25). It is based on the tenet that the change in free energy that occurs after mutation of a single residue depends on the surrounding residues. If mutation of a second residue affects the free-energy change caused by mutation of the first residue, the two residues will be interdependent and potentially can interact directly; however, evidence for direct interaction relies on independent structural information. For the data presented here, we computed the free-energy change produced by each mutation from estimates of Θ2 from kinetic fitting of single-channel dwell times. The double-mutant cycles for αR209Q and αE45R, shown in Fig. 2 b, demonstrate large interresidue coupling free energies of >3 kcal/mol for both the human and mouse AChRs activated by ACh. These coupling free energies are very similar to that obtained previously for human AChR activated by ACh (14), and are much greater than twice the SE, a convention used to indicate a significant coupling free energy (22). Thus, αArg209 and αGlu45 show strong energetic coupling in both human and mouse AChRs.

Because species differences do not account for the divergent estimates of energetic coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45, we evaluated a second difference in experimental conditions, the type of agonist, and compared the full agonist ACh with the partial agonist Ch. We initially examined the functional consequences of the αE45R mutation with Ch because this combination of mutation and agonist showed enhanced rather than diminished channel gating (16). Channel openings were elicited by a range of Ch concentrations that produced clearly identifiable clusters but minimized channel block, and then Scheme 1 was fitted to each set of global closed and open dwell times. For WT human and mouse AChRs activated by Ch, channel openings within clusters were very infrequent even at a concentration of 6 mM Ch, the highest concentration tested (Fig. 3). For both species of AChR, the fitted PDFs overlay the set of global dwell time histograms (Fig. 3, Fig. S5, and Fig. S6), yielding channel gating equilibrium constants of 0.07 (Table 2), in good agreement with previous estimates (16,26). By contrast, in both human and mouse AChRs, the αE45R mutant activated by Ch shows a much greater frequency of openings within clusters compared with the WT AChR (Fig. 3). In addition, individual channel openings are briefer. For αE45R AChRs from both species, the fitted PDFs closely overlay the global set of dwell-time histograms (Fig. 3, Fig. S5, and Fig. S6), yielding channel gating equilibrium constants 3- to 7-fold greater than those for WT AChRs (Table 2). The increases in channel gating arise from marked increases in the channel opening rate constant β2, which are partially countered by increases in the channel closing rate constant α2. Thus, for ACh and Ch, the αE45R mutant produces opposite changes in channel gating, indicating that this mutation produces an energy landscape for gating that differs between the two agonists. Furthermore, the agonist dependence of αE45R suggests that ACh and Ch produce different structural changes within the ligand-binding domain that are realized as far away as αGlu45.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of activation of human and mouse AChRs and the αE45R mutant. Currents elicited by 3 mM Ch are shown at a bandwidth of 10 kHz, with channel openings shown as upward deflections. Histograms of closed and open dwell times within identified clusters of events are shown on logarithmic time axes with PDFs generated from global kinetic fitting overlaid (see Materials and Methods; fitted rate constants are given in Table 2).

Table 2.

Kinetics of activation by choline of human and mouse AChRs expressed in BOSC 23 cells.

| Receptor | k+1 | k−1 | K1(μM) | k+2 | k−2 | K2 (μM) | β1 | α1 | Θ1 | β2 | α2 | Θ2 | k+b | k−b | Kb(mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H Wild-type | 7 ± 2 | 4500 ± 1200 | 640 | 3 ± 1 | 9000 ± 2300 | 3000 | ND | ND | - | 110 ± 6 | 1700 ± 600 | 0.065 ± 0.021 | 1 ± 0.2 | 110000 ± 7100 | 110 |

| H αE45R | 20 ± 1 | 8100 ± 320 | 400 | 10 ± 1 | 1600 ± 4000 | 160 | ND | ND | - | 1000 ± 20 | 5000 ± 500 | 0.2 ± 0.019 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 160000 ± 23000 | 80 |

| H αE45R αR209Q | ND | ND | - | ND | ND | - | ND | ND | - | 90 ± 2 | 3000 ± 30 | 0.026 ± 0.0006 | 21.3 ± 5.8 | 240000 ± 6300 | 11 |

| M Wild-type | ND | ND | - | ND | ND | - | ND | ND | - | 70 ± 1 | 1007 ± 20 | 0.069 ± 0.0016 | 1 ± 0.07 | 150000 ± 2500 | 150 |

| M αE45R | 3 ± 0.3 | 9200 ± 2300 | 3100 | 40 ± 8 | 75000 ± 7000 | 1900 | ND | ND | - | 3800 ± 400 | 7600 ± 100 | 0.5 ± 0.052 | 1.6 ± 0.14 | 140000 ± 1600 | 140 |

| M αE45R αR209Q | 10 ± 2 | 48000 ± 8700 | 4800 | 5 ± 0.8 | 24000 ± 350 | 4800 | ND | ND | - | 500 ± 10 | 5200 ± 250 | 0.097 ± 0.023 | 1 ± 0.2 | 130000 ± 5600 | 130 |

Values are from global fits of Scheme 1 to data obtained over a range of choline concentrations (see Figs. S5 and S6), with standard errors given (Materials and Methods). Rate constants are in units of μM-1s-1 for association rate constants, and s-1 for all others. ND indicates parameters were not defined. H- indicates human receptor, M- indicates mouse receptor.

The question remains, however, of whether αArg209 and αGlu45 show energetic coupling with Ch as the agonist. We could not address this question quantitatively because the mutation αR209Q reduced the frequency of channel openings so that clusters of openings from the same AChR channel were not apparent (data not shown). Nevertheless, the marked reduction in channel opening frequency suggests that αR209Q decreases the efficiency of channel gating elicited by Ch, although the extent of the decrease cannot be quantified. On the other hand, we asked whether the double mutation αE45R/αR209Q counteracted the increase in channel gating produced by αE45R alone. When tested in both mouse and human AChRs, the double mutation decreased the channel gating equilibrium constant for Ch compared with αE45R alone (Table 2), and approached that for the WT AChR. Thus, although energetic coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45 cannot be quantified with Ch as the agonist, simultaneous mutation of both residues restores channel gating to normal.

Previous studies showed that hydrophobic substitutions for αGlu45 enabled a rapid rate of channel opening accompanied by efficient channel gating (15,16). Because αGlu45 and αArg209 are physically associated and functionally coupled, a potential explanation is that charge neutralization of αGlu45 is compensated for by another local negative charge. In the cryo-EM structure of the Torpedo AChR (10), and in x-ray structures of the α1 extracellular domain (11) and the prokaryotic channel ELIC (13), a second negative charge, at a position equivalent to αGlu175 in the β8-β9 loop, is near the Arg equivalent to αArg209 (Fig. 1 b). To determine whether αGlu175 contributes to channel gating, we generated the charge-reversal mutation αE175R and recorded single-channel currents activated by ACh. The single-channel current traces show brief channel openings with long intervening closings, indicating that αE175R attenuates channel gating (Fig. 4 a). The fitted PDFs for Scheme 1 describe the closed- and open-dwell-time distributions, and the fitted rate constants show that β2 decreases and α2 increases compared with the human WT AChR, resulting in a 67-fold reduction in Θ2 (Table 3). Thus, αGlu175, located near αArg209, is required for rapid and efficient channel gating, suggesting that the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating also depends on αGlu175.

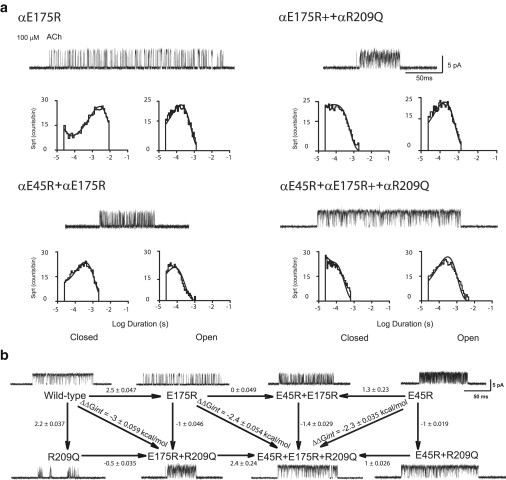

Figure 4.

(a) Kinetics of activation of charge-reversal mutations in human AChR. Currents elicited by 100 μM ACh are shown at a bandwidth of 10 kHz, with channel openings shown as upward deflections. Histograms of closed and open dwell times within identified clusters of events are shown on logarithmic time axes with probability density functions generated from global kinetic fitting overlaid (see Materials and Methods; fitted rate constants are given in Table 3). (b) Interresidue energetic coupling as in Fig. 2 b.

Table 3.

Kinetics of activation by ACh of human AChRs expressed in BOSC 23 cells.

| Receptor | k+1 | k−1 | K1 (μM) | k+2 | k−2 | K2 (μM) | β1 | α1 | Θ1 | β2 | α2 | Θ2 | k+b | k−b | Kb (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 350 ± 40 | 3500 ± 440 | 10 | 90 ± 2 | 19000 ± 300 | 211 | 60 ± 6 | 3500 ± 300 | 0.02 | 43000 ± 1100 | 2100 ± 40 | 20.4 ± 0.67 | 30 ± 3 | 162000 ± 4000 | 5.0 |

| αE45R | 210 ± 30 | 240 ± 70 | 1.1 | 450 ± 30 | 1300 ± 70 | 2.8 | 240 ± 50 | 9000 ± 110 | 0.03 | 21000 ± 150 | 7400 ± 50 | 2.8 ± 0.028 | 35 ± 2 | 116000 ± 23000 | 3.0 |

| αR209Q | 270 ± 9 | 1900 ± 90 | 7.0 | 130 ± 4 | 11000 ± 510 | 85 | 20 ± 3 | 3300 ± 310 | 0.006 | 10000 ± 460 | 19000 ± 470 | 0.5 ± 0.027 | 90 ± 20 | 90000 ± 10400 | 0.9 |

| αE175R | 240 ± 10 | 13000 ± 7000 | 54 | 120 ± 7 | 26000 ± 1300 | 220 | ND | ND | - | 2100 ± 150 | 6000 ± 60 | 0.34 ± 0.025 | 30 ± 3 | 120000 ± 9000 | 4.5 |

| αE45R αR209Q | 360 ± 6 | 3800 ± 80 | 10 | 180 ± 3 | 7500 ± 140 | 42 | ND | ND | - | 30500 ± 800 | 1900 ± 30 | 16 ± 0.49 | 30 ± 1 | 107000 ± 1100 | 3.5 |

| αE45R + αE175R | 570 ± 15 | 750 ± 20 | 1.3 | 290 ± 7 | 1500 ± 40 | 5.2 | ND | ND | - | 4600 ± 170 | 15000 ± 110 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 60 ± 3 | 120000 ± 4500 | 2.0 |

| αE175R + αR209Q | 320 ± 8 | 3400 ± 77 | 10.6 | 160 ± 4 | 6500 ± 170 | 40.6 | 270 ± 30 | 42000 ± 4500 | 0.006 | 18000 ± 420 | 15000 ± 500 | 1.2 ± 0.048 | 150 ± 5 | 90000 ± 20000 | 0.6 |

| αE45R + αE175R + αR209Q | 500 ± 10 | 3300 ± 60 | 6.0 | 260 ± 5 | 6700 ± 130 | 2.6 | 250 ± 6 | 19000 ± 130 | 0.013 | 17000 ± 500 | 4100 ± 40 | 4.2 ± 0.06 | 20 ± 1 | 105000 ± 20000 | 4.0 |

Values are from global fits of Scheme 1 to data obtained over a range of ACh concentrations (see Figs. S1–S4), with standard errors given (Materials and Methods). Rate constants are in units of μM-1s-1 for association rate constants, and s-1 for all others. ND indicates parameters were not defined.

To test this possibility, we combined mutations of αArg209 and αGlu175 into the same AChR and recorded single-channel currents activated by ACh. Recordings from the double mutant αR209Q/αE175R show enhanced channel gating compared with that of either single mutation, exhibiting brief channel openings flanked by brief closings (Fig. 4 a). The fitted PDFs describe the closed- and open-time distributions, and the fitted rate constants indicate increases in Θ2 compared with that obtained for either single mutant, although it remains 17-fold smaller than the Θ2 obtained for the WT AChR (Table 3). A limitation of these data is that both β2 and α2 are large and similar in magnitude, a situation in which both approximate and exact missed-event correction methods can underestimate the two rate constants. Nevertheless, the large decrease in channel gating produced by the mutation αR209Q is partially mitigated by the charge reversal of αGlu175.

The findings to this point show that both αGlu45 and αGlu175 contribute to channel gating. To determine whether αGlu45 and αGlu175 contribute jointly to channel gating, we substituted Arg for both αGlu45 and αGlu175 and recorded single-channel currents activated by ACh. For the double charge-reversal mutation αE175R/αE45R, the single-channel current traces show brief channel openings with long intervening closings (Fig. 4 a) similar to those observed for the αE175R mutation alone. The fitted PDFs describe the closed- and open-time distributions, and the fitted rate constants show that Θ2 is reduced by 67-fold compared with that for the WT AChR (Table 3). For the double mutant αE175R/αE45R, the change in Θ2 is the same as that for the single mutant αE175R, indicating the functional consequences of the two mutations are not additive; thus, αGlu45 and αGlu175 contribute to channel gating interdependently.

To determine whether the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating depends on αGlu45 and αGlu175, we generated the triple mutant αR209Q/αE45R/αE175R. Because both the αR209Q and αE45R/αE175R mutations markedly suppress channel gating, a further suppression of gating would be expected if their contributions were independent. However the triple-mutant AChR shows strikingly enhanced channel gating compared with either the single- or double-mutant AChRs (Fig. 4 a). The fitted rate constants reveal a Θ2 of 4.2, which is 14-fold greater than that of the double mutant αE45R/αE175R (Table 3). Thus, the contribution of αArg209 to channel gating depends on both αGlu45 and αGlu175.

Given our estimates of Θ2 for the single-, double-, and triple-mutant AChRs, we generated several mutant cycles to quantify interresidue coupling free energies within the triad αArg209, αGlu45, and αGlu175. For the combination αR209Q and αE175R, the double-mutant cycle (shown in the left box in Fig. 4 b) reveals a coupling free energy of −3 kcal/mol, which is similar to that for the αR209Q/αE45R mutant cycle (Fig. 2 b). For the cycle in which the mutation αE45R is present at all four vertices (right box in Fig. 4 b), αR209Q and αE175R remain strongly coupled, but the coupling free energy decreases by a third. This decrease may arise because in the context of αR209Q, the two positive charges, αE175R and αE45R, are mutually repulsive. Conversely, for the cycle in which the mutation αE175R is present at all four vertices (center box in Fig. 4 b), αR209Q and αE45R remain strongly coupled, as in Fig. 2 b, but the coupling free energy again decreases by almost a third. Thus, in contributing to channel gating, both αGlu175 and αGlu45 exhibit strong energetic coupling with αArg209, and charge reversal of either anionic residue reduces coupling between the remaining anionic residue and αArg209.

If the tripartite interaction between αGlu45, αGlu175, and αArg209 is purely electrostatic, substitution of a hydrophobic residue for either anionic residue might be expected to reduce the channel gating equilibrium constant. However, substitution of either Leu for αGlu45 or Val for αGlu175 results in long channel openings flanked by brief closings, indicating that channel gating remains efficient (Fig. 5). For both the αE45L and αE175V mutations, the fitted PDFs describe the closed- and open-time histograms, and the fitted rate constants show a slight slowing of the channel opening rate constants β2 and little change of the channel closing rate constants α2, yielding Θ2 estimates of 8 and 18, respectively, compared with 20 for the WT AChR (Table S1). Thus, hydrophobic substitutions for either αGlu45 or αGlu175 retain efficient channel gating, suggesting that the remaining anionic residue may compensate for loss of the negative charge produced by the substituted hydrophobic residue.

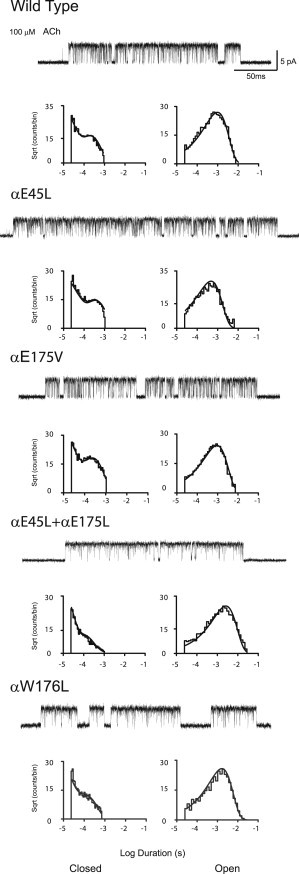

Figure 5.

Kinetics of activation of hydrophobic mutations in the human AChR Currents elicited by 100 μM ACh are shown at a bandwidth of 10 kHz, with channel openings shown as upward deflections. Histograms of closed and open dwell times are shown with PDFs computed from global kinetic fitting overlaid (Table S1).

To test the idea of charge compensation, we substituted Leu for both αGlu45 and αGlu175 and measured single-channel currents elicited by ACh. However, the double-mutant AChR exhibits long channel openings flanked by brief closings, indicating that channel gating remains efficient (Fig. 5). The fitted PDFs describe the closed- and open-time histograms, and the fitted rate constants reveal a slowing of the channel closing rate constant α2 resulting in an increase of Θ2 (Table S1). Thus, substituting Leu for both αGlu45 and αGlu175 enhances rather than diminishes channel gating. Loss of the two negative charges may have been compensated for by the steric bulk of the substituted Leu residues or yet another nearby anionic residue, or both.

A third, potentially compensating residue, the conserved αTrp176, is also near αArg209 (Fig. 1 b). To determine whether αTrp176 contributes to channel gating, we generated the mutation αW176L and recorded single-channel currents elicited by ACh. The resulting single-channel current traces exhibit long channel openings flanked by brief closings, indicating that channel gating remains efficient (Fig. 5). The fitted PDFs describe the closed- and open-time distributions, and the fitted rate constants show decreases in the channel gating rate constants β2 and α2 that together produce a slight increase of Θ2 (Table S1). A second mutation, αW176V, reduces Θ2 by more than half (Table S1), perhaps owing to the smaller size of Val. However, substituting αTrp176 with Ala or anionic or polar residues did not yield functional channels (data not shown). Thus, the functional consequences of αW176L and αW176V are reminiscent of those of the hydrophobic mutations αE175V, E45L, and αE45L/αE175L (Table S1).

To test whether retention of efficient channel gating by the double mutant αE45L/αE175L is compensated for by αTrp176, we substituted Leu for all three residues and recorded single currents activated by ACh. Recordings from the triple-mutant AChR showed kinetically heterogeneous channel openings and closings (Fig. 6 a), suggesting multiple gating modes, unlike the other mutant AChRs examined herein. Kinetic heterogeneity was evident as abrupt switches in the pattern of openings and closings within clusters, and also in the wide range of open probabilities among clusters that showed no abrupt switches. For the triple-mutant AChR, channel open probabilities within clusters were reduced overall and spanned a wide range, in contrast to the high open probability and narrow range observed for the WT AChR (Fig. 6 b). Thus, substituting Leu for all three electron-rich residues surrounding αArg209 suppresses channel gating and produces inhomogeneous kinetics. Therefore, although the triple mutation removes three electron-rich residues, the steric bulk of the three substituted Leu residues may partially compensate for this loss.

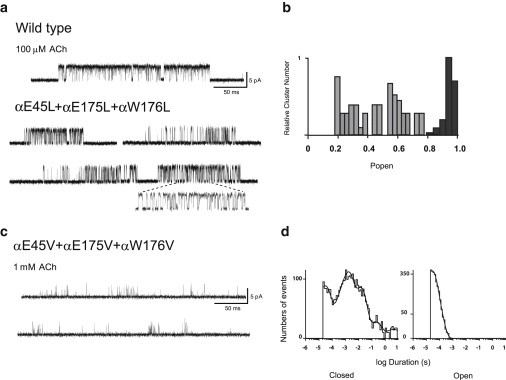

Figure 6.

(a) Single-channel currents elicited by 100 μM ACh from WT and the triple-Leu-substituted AChR at a bandwidth 10 kHz. (b) Histogram of cluster mean open probability (Popen) shows a broad distribution for the triple mutant (gray bars), indicating heterogeneous kinetics, but the distribution is narrow for the WT AChR (black bars). (c) Single-channel currents elicited by 1 mM ACh from the triple-Val-substituted AChR. Clusters could not be identified even at a concentration of 1 mM ACh. (d) Open and closed time histograms were fitted by sums of exponentials using the program TAC.

To test further for steric contributions of the three electron-rich residues, we substituted Val for αGlu45, αGlu175, and αTrp176, and recorded single-channel currents elicited by ACh. The recordings show profoundly attenuated channel gating marked by very brief channel openings flanked by prolonged closings (Fig. 6 c). Furthermore, to obtain sufficient numbers of channel openings for dwell-time analysis, we had to increase the ACh concentration to 1 mM. However, even at this high concentration, the frequency of openings was so low that clusters of channel openings were not apparent. Thus, although kinetic fitting was not possible (Fig. 6 d), substituting the smaller Val for αGlu45, αGlu175, and αTrp176 profoundly impairs channel gating, suggesting that the three substituted Val residues do not provide sufficient steric bulk surrounding αArg209.

Discussion

We examined the functional contributions of residues within the structural transition zone between the ligand-binding and pore domains of the muscle-type AChR. The starting point for this study was the profound attenuation of agonist-mediated channel gating produced by mutations of the invariant residue αArg209, together with restoration of efficient channel gating after charge reversal of both αArg209 and the nearby αGlu45 (14). Determination of interresidue energetic coupling, based on changes in channel gating after residue substitutions, revealed strong coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45. These observations are consistent with the available structural data suggesting that αArg209 and αGlu45 form a salt bridge within the hydrophobic interior of the subunit (10). Other studies, however, showed that hydrophobic substitutions of αGlu45 had small effects on agonist-mediated channel gating (14–16), contrary to expectations based on a single, functionally crucial salt bridge. Furthermore, the coupling free energy between αArg209 and αGlu45 was large when examined in human AChR with ACh as the agonist (14), but was significantly smaller when examined in mouse AChR with a combination of ACh and Ch (16). To clarify these issues, we evaluated whether other nearby electron-rich residues contribute to channel gating through interaction with αArg209, compared the coupling free energy between αArg209 and αGlu45 in human versus mouse AChRs, and compared the functional consequences of the mutation αE45R with either ACh or Ch as the agonist.

The coupling free energies presented here are computed from the channel gating equilibrium constant Θ2 obtained by fitting Scheme 1 to single-channel dwell times obtained over a range of ACh concentrations. However, Θ2 is a composite parameter, which can be understood by expanding Scheme 1 as follows:

| Scheme 2 |

The doubly occupied receptor A2R, rather than leading directly to the open state, first undergoes a priming step, defined by the priming rate constants p+ and p−, to form the primed closed state A2R″ from which the channel opens (24). In the original primed mechanism, priming occurred in two separate steps, but Scheme 2 contains only a single priming step, which is equivalent to the flip step in the initial work that justified expansion of Scheme 1 (23). Because the mean duration of the A2R″ state is briefer than 10 μs, an instrumentation dead time of 22 μs eliminates most of the corresponding closed dwell times. Thus Θ2, obtained by fitting Scheme 1 to the data, is given by (P/(1+P))ΘIntrinsic, where P = p+/p− and ΘIntrinsic = β2/α2 (23). As a consequence, an interpretive limitation is that mutations that alter Θ2 may alter the priming step or the gating step, or a combination of the two.

Analogous reasoning applies in principle to the binding dissociation constants, K1 and K2, obtained by fitting Scheme 1 to the data. Like the apparent gating equilibrium constant, K1 and K2 are apparent dissociation constants with contributions from both intrinsic binding and priming equilibrium constants. However, unlike the apparent gating equilibrium constant, relating the apparent K1 and K2 to the intrinsic binding and priming equilibrium constants depends on the sequence of the binding and priming steps, for which there are several possibilities according to the primed mechanism (24). Furthermore, by altering a subset of the rate constants, a mutant could conceivably alter the sequence of steps, making comparison problematic. Because gating is a terminal step immediately preceded by priming, the issue of the sequence of steps does not arise. Thus, this study focuses on energetic coupling based on the apparent gating equilibrium constants.

Recent studies showed that the priming step, or the equivalent flip step, is strongly agonist dependent, with P being large for full agonists but small for weak agonists, whereas the intrinsic channel gating step is similar for different agonists (23,27). This relationship among P, ΘIntrinsic, and the type of agonist may reconcile the difference in coupling free energies between αArg209 and αGlu45 for human AChRs activated by ACh versus mouse AChRs activated by a combination of ACh and Ch. For the mutant cycle with human AChR, ACh was the agonist for all four members of the cycle (14), as in Fig. 3, whereas for the mutant cycle with mouse AChR, Ch was the agonist for three members and ACh was the agonist for the fourth member (16). In comparing the two studies, the tacit assumption was that the relative changes in Θ2 produced by each mutation would be the same for ACh and Ch (16). However, we found that although the αE45R mutant activated by ACh showed a decrease in Θ2, αE45R activated by Ch showed an increase. Thus, the functional consequences of the αE45R mutant depend on the type of agonist. Because the priming step diverges between the two agonists, and the channel-gating step is agonist independent, a favored hypothesis is that the αE45R mutation affects the priming step differently for the two agonists but does not affect the intrinsic gating step, giving rise to agonist dependence of the apparent gating step. Furthermore, the low degree of coupling between αArg209 and αGlu45 observed in previous studies (16) likely originated from the agonist-dependent functional consequences of αE45R.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of an AChR mutation that alters the apparent channel-gating equilibrium constant in an agonist-dependent manner. However, AChR mutations that produce agonist-dependent functional consequences are likely uncommon. A recent study of several agonists and AChR mutations led to the conclusion that changes in the channel gating equilibrium constant are agonist independent (28). In fact, as shown in Tables 1 and 2, channel gating for the double mutation αE45R/αR209Q approaches that of the WT AChR for both ACh and Ch. Thus, whether the functional consequences of a mutation are agonist dependent likely depends on both the site of the mutation and the substituting residue. The underlying structural and mechanistic bases of the agonist dependence remain unclear and call for further studies using different agonists, sites of substitution, and substituting residues.

Structural determination of the AChR and other receptors from the Cys-loop family shows that αArg209 or the equivalent residue projects from β-strand 10 into the hydrophobic interior of the subunit (10–13,29). The positive charge on the guanidinium side chain is delocalized across the three nitrogen atoms, and the hydrocarbon portion of the side chain increases hydrophobicity. These unique properties of Arg may explain why it is stable within the hydrophobic interior of the subunit, and why it is the only side chain at an equivalent position in all eukaryotic and the vast majority of prokaryotic Cys-loop receptors. Residues surrounding αArg209 stem from multiple loops of the extracellular domain, are chemically compatible with Arg, and are conserved among all AChR α-subunits. These residues include αGlu45 from the β1-β2 loop, αGlu175 and αTrp176 from the β8-β9 loop, and αAsp138 from the Cys-loop. A high-resolution structure of a full-length AChR is needed to resolve the question of whether these electron-rich residues physically associate with αArg209.

In all four AChR subunits, a central cationic residue surrounded by multiple electron-rich residues is likely present. In the non-α-subunits, Arg is conserved at positions equivalent to αArg209, and the surrounding electron-rich residues are also conserved (except in the β-subunit, where the residue equivalent to αGlu175 is Gln). This raises the question of what distinguishes the α-subunit from the non-α-subunits in terms of signal transduction. The central cationic Arg is crucial in all of the subunits, because mutation of non-α-subunit residues equivalent to αArg209 attenuated channel gating to an extent similar to that observed for αR209Q (30). However, the surrounding electron-rich residues appear to be most important in the α-subunit, although not all residues have been examined. Mutations of residues near αArg209, αGlu45, αVal46, αSer269, and αPro272 produced large changes in channel gating, whereas mutations of equivalent residues in the non-α-subunits produced smaller or no changes (14). The subunit-selective contributions of these residues near αArg209 may be a consequence of the structural specialization of the α-subunits for agonist recognition. Thus, by virtue of forming the principal face of the AChR ligand-binding site, the α-subunit is the most decisive subunit in the transduction of agonist binding into rapid and efficient channel gating.

Our findings reveal multiple interresidue interactions between αArg209 and chemically compatible residues in the same region. Charge reversal of a second anionic residue, αGlu175, sharply reduces channel gating efficiency, and mutant cycle analyses show strong coupling between αGlu175 and αArg209. Furthermore, charge reversal of both αGlu45 and αGlu175 relieves suppression of channel gating caused by the mutation αR209Q, and mutant cycle analysis shows that αGlu45, αGlu175, and αArg209 contribute to channel gating interdependently. The interresidue interactions are not purely electrostatic, however, because substitution of bulky, hydrophobic residues for the two anionic residues enables efficient channel gating, suggesting that additional residues, such as αTrp176, interact with αArg209. Substituting Leu for αGlu45, αGlu175, and αTrp176 suppresses channel gating and produces heterogeneous kinetics, suggesting that the large Leu side chains compensate in part for loss of the three electron-rich residues. However, substituting the smaller Val for αGlu45, αGlu175, and αTrp176 results in barely detectable channel gating, suggesting that the smaller Val side chains do not supply enough steric bulk around αArg209. A fourth candidate partner of αArg209, αAsp138, was not evaluated because the double mutation αR209E/αD138R showed no channel activity (our own unpublished observations). The emerging picture is one in which the invariant αArg209 lodges within the hydrophobic interior of the subunit, where it is surrounded by multiple residues of sufficient electron density or size, or both. Residues surrounding αArg209 can vary, however. Among eukaryotic Cys-loop receptor subunits, the residue equivalent to αGlu45 is usually Glu but can also be Asp, the residue equivalent to αGlu175 is usually Glu but can also be Gln, and the residue equivalent to αTrp176 is always aromatic. However, in prokaryotic Cys-loop receptors, residues surrounding αArg209 show greater diversity. The residue equivalent to αGlu45 is usually Glu but can also be Asp, Ile, Ala, Pro, or Trp; the residue equivalent to αGlu175 is usually Glu but can also be Gly, Arg, Ser, or Asn; and the residue equivalent to αTrp176 is usually aromatic but can also be Thr or Asp (31). Thus, in the transition from prokaryotic to eukaryotic Cys-loop receptors, residues surrounding αArg209 became more conserved and electron rich, perhaps to increase the efficiency of signal transduction to meet physiological needs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Free for outstanding technical contributions, and T. Therneau for help with statistical analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NS31744 to S.M.S.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Sine S.M. The nicotinic receptor ligand binding domain. J. Neurobiol. 2002;53:431–446. doi: 10.1002/neu.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taly A., Corringer P.J., Changeux J.P. Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:733–750. doi: 10.1038/nrd2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celie P.H., van Rossum-Fikkert S.E., Sixma T.K. Nicotine and carbamylcholine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as studied in AChBP crystal structures. Neuron. 2004;41:907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao F., Bren N., Sine S.M. Agonist-mediated conformational changes in acetylcholine-binding protein revealed by simulation and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:8443–8451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen S.B., Sulzenbacher G., Bourne Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. EMBO J. 2005;24:3635–3646. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li S., Huang S., Chen L. Ligand-binding domain of an α7-nicotinic receptor chimera and its complex with agonist. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1253–1259. doi: 10.1038/nn.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H.L., Toghraee R., Sine S.M. Single-channel current through nicotinic receptor produced by closure of binding site C-loop. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3582–3590. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhtasimova N., Free C., Sine S.M. Initial coupling of binding to gating mediated by conserved residues in the muscle nicotinic receptor. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;126:23–39. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosman C., Zhou M., Auerbach A. Mapping the conformational wave of acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Nature. 2000;403:773–776. doi: 10.1038/35001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:967–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellisanti C.D., Yao Y., Chen L. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of nAChR alpha1 bound to alpha-bungarotoxin at 1.94 A resolution. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:953–962. doi: 10.1038/nn1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bocquet N., Nury H., Corringer P.J. X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009;457:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature07462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilf R.J., Dutzler R. Structure of a potentially open state of a proton-activated pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2009;457:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature07461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee W.Y., Sine S.M. Principal pathway coupling agonist binding to channel gating in nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2005;438:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature04156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee W.Y., Free C.R., Sine S.M. Binding to gating transduction in nicotinic receptors: Cys-loop energetically couples to pre-M1 and M2-M3 regions. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:3189–3199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6185-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purohit P., Auerbach A. Acetylcholine receptor gating at extracellular transmembrane domain interface: the “pre-M1” linker. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;130:559–568. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee B.S., Gunn R.B., Kopito R.R. Functional differences among nonerythroid anion exchangers expressed in a transfected human cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11448–11454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohno K., Wang H.L., Engel A.G. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by decreased agonist binding affinity due to a mutation in the acetylcholine receptor ε subunit. Neuron. 1996;17:157–170. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee W.Y., Sine S.M. Invariant aspartic Acid in muscle nicotinic receptor contributes selectively to the kinetics of agonist binding. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;124:555–567. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colquhoun D., Sigworth F. Fitting and statistical analysis of single channel records. In: Sakmann B., Neher E., editors. Single Channel Recording. Plenum Publishing; New York: 1983. pp. 191–264. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin F., Auerbach A., Sachs F. Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch-clamp data containing missed events. Biophys. J. 1996;70:264–280. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber G., Fersht A.R. Energetics of protein-protein interactions: analysis of the barnase-barstar interface by single mutations and double mutant cycles. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;248:478–486. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lape R., Colquhoun D., Sivilotti L.G. On the nature of partial agonism in the nicotinic receptor superfamily. Nature. 2008;454:722–727. doi: 10.1038/nature07139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukhtasimova N., Lee W.Y., Sine S.M. Detection and trapping of intermediate states priming nicotinic receptor channel opening. Nature. 2009;459:451–454. doi: 10.1038/nature07923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughan C.K., Harryson P., Fersht A.R. A structural double-mutant cycle: estimating the strength of a buried salt bridge in barnase. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:591–600. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902001567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen X.M., Deymeer F., Engel A.G. Slow-channel mutation in acetylcholine receptor alphaM4 domain and its efficient knockdown. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:128–136. doi: 10.1002/ana.20861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lape R., Krashia P., Sivilotti L.G. Agonist and blocking actions of choline and tetramethylammonium on human muscle acetylcholine receptors. J. Physiol. 2009;587:5045–5072. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purohit P., Bruhova I., Auerbach A. Sources of energy for gating by neurotransmitters in acetylcholine receptor channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:9384–9389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203633109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibbs R.E., Gouaux E. Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature. 2011;474:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature10139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruhova I., Auerbach A. Subunit symmetry at the extracellular domain-transmembrane domain interface in acetylcholine receptor channel gating. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:38898–38904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tasneem A., Iyer L.M., Aravind L. Identification of the prokaryotic ligand-gated ion channels and their implications for the mechanisms and origins of animal Cys-loop ion channels. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.