A typical question we ask about the molecular components of a cell is, how do they contribute to the cell’s physiological function? Another pertinent question, however, has to do with their simultaneous contribution to the cell’s structural properties. It is important to understand how the molecular components act together as a whole to give rise to cellular function, but is that whole structurally sound? The question of how the structural resilience of the cell vis à vis its specific environment can be affected by mutant enzymes or mislocalized components is a critical one for understanding cellular function and pathology. In this issue of Biophysical Journal, Haeri et al. (1) tackle this question in the case of the rod photoreceptor outer segment. The rod photoreceptors of the vertebrate retina are the cells that are responsible for dim light vision and have achieved the ultimate in sensitivity, being able to detect single photons (2). Phototransduction, the conversion of light to electrical signal, takes place in the outer segment of the rod photoreceptor. The outer segment is a cylindrically shaped, modified cilium that contains several hundred flattened membrane sacs, the disks, stacked on top of each other (see Fig. 1). The disk membranes are packed with the primary light detector, the visual pigment protein rhodopsin. The large membrane surface area provided by these hundreds of disks accommodates a large number of rhodopsin molecules, ensuring a high probability of absorption and detection of incident photons. Absorption of a photon activates rhodopsin and triggers a cascade of reactions that take place on the surface of the disk and result in a reduction in the concentration of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, the intracellular transmitter of phototransduction. Phototransduction is arguably the best-understood signal transduction process, and our detailed understanding of this process ranges from individual molecular components to the light response of the cell. This level of understanding is exemplified by the development of mathematical models that can quantify the contribution of outer-segment cytoarchitecture to the shaping of the light response (3,4).

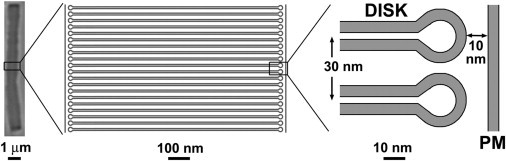

Figure 1.

Structure of the vertebrate rod outer segment. A mouse rod outer segment is shown on the left for illustrative purposes. The width of a disk, the spacing between disks, and the distance between disks and the plasma membrane (PM) are similar across species; the diameter and length of the outer segment vary widely.

Outer segments undergo a continuous process of renewal, with tens of new disks being added daily at their base. The addition of new disks at the base is balanced by the daily phagocytosis of disks at the tip of the outer segment by the adjacent retinal pigment epithelial cells, which maintains the outer-segment length (5). The formation of new disks depends on the trafficking of newly synthesized components, including rhodopsin, from the cell body into the outer segment (6). Proper trafficking and targeting of these components are critical for maintaining the integrity of outer-segment structure and function, and have been studied for many years (7,8). However, a quantitative model linking the structural properties of the outer segment to its composition has been lacking. This gap in our understanding is now being addressed by Haeri et al. (1), who have developed a novel (to our knowledge) tool for analyzing the relation between the axial composition and structural properties of outer segments. This tool consists of a model of the mechanical rigidity of the rod outer segment based on its axial density. With this tool in hand, and using high-resolution confocal imaging, they analyzed outer-segment flexing and disruption in living rods from transgenic Xenopus expressing a fluorescently tagged rhodopsin (rhodopsin-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)). The eGFP-rhodopsin provided the means to monitor variations in the axial density of the outer segment, variations that depend on the photoreceptor’s history of light exposure. Analyzing experimental observations with the model, they estimated a bending stiffness for the Xenopus rod outer segment on the order of 105 nN.μm2, which is several orders of magnitude larger than that reported for other cilia. An important insight provided by the model is the way in which the pattern of axial density variation affects the rigidity of the outer segment. The model makes interesting predictions that are readily testable experimentally; for example, outer segments are predicted to tend to break in regions of higher density, consistent with the observation of breaks mostly in regions with higher levels of eGFP-rhodopsin. Another prediction of the model is that thinner outer segments, such as those of mammals, are less fragile than the wider ones of amphibian species.

For photoreceptor cell biology, the model provides a new framework for thinking about long-standing observations of density variations along the length of the outer segment (9), and the banding expression of eGFP-rhodopsin in transgenic Xenopus (10). It provides a means of analyzing how defects in the trafficking of components from the cell body to the outer segment can result in axial inhomogeneities and structural weakening. Such analysis will be especially valuable because molecular defects can result in major outer-segment malformation, or even complete failure to form outer segments or their components (11,12). Beyond photoreceptors, this work raises a host of intriguing questions about the structural resilience of cilia and other rod-like organelles. Outer segments may lead a long and quiet life in the retina, but cilia in other cell types beat to generate sufficient force to propel mucus (13), and the stereocilia of the hair cells in the ear have to sustain and respond to the forces generated by sound waves (14). Cilia are found on almost all vertebrate cells and play an important role in normal cell function. Defects in their function are associated with ciliopathies, a diverse group of developmental and degenerative diseases (15).

References

- 1.Haeri M., Knox B.E., Ahmadi A. Modeling the flexural rigidity of rod photoreceptors. Biophys. J. 2013;104:300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arshavsky V.Y., Burns M.E. Photoreceptor signaling: supporting vision across a wide range of light intensities. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:1620–1626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.305243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreucci D., Bisegna P., DiBenedetto E. Mathematical model of the spatio-temporal dynamics of second messengers in visual transduction. Biophys. J. 2003;85:1358–1376. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74570-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisegna P., Caruso G., DiBenedetto E. Diffusion of the second messengers in the cytoplasm acts as a variability suppressor of the single photon response in vertebrate phototransduction. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3363–3383. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young R.W., Bok D. Participation of the retinal pigment epithelium in the rod outer segment renewal process. J. Cell Biol. 1969;42:392–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.2.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deretic D., Papermaster D.S. Polarized sorting of rhodopsin on post-Golgi membranes in frog retinal photoreceptor cells. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1281–1293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marszalek J.R., Liu X., Goldstein L.S. Genetic evidence for selective transport of opsin and arrestin by kinesin-II in mammalian photoreceptors. Cell. 2000;102:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pazour G.J., Baker S.A., Besharse J.C. The intraflagellar transport protein, IFT88, is essential for vertebrate photoreceptor assembly and maintenance. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corless J.M., Kaplan M.W. Structural interpretation of the birefringence gradient in retinal rod outer segments. Biophys. J. 1979;26:543–556. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85270-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moritz O.L., Tam B.M., Nakayama T. A functional rhodopsin-green fluorescent protein fusion protein localizes correctly in transgenic Xenopus laevis retinal rods and is expressed in a time-dependent pattern. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:28242–28251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilliam J.C., Chang J.T., Wensel T.G. Three-dimensional architecture of the rod sensory cilium and its disruption in retinal neurodegeneration. Cell. 2012;151:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung C.H., Chuang J.Z. The cell biology of vision. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:953–963. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teff Z., Priel Z., Gheber L.A. Forces applied by cilia measured on explants from mucociliary tissue. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1813–1823. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudspeth A.J., Corey D.P. Sensitivity, polarity, and conductance change in the response of vertebrate hair cells to controlled mechanical stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:2407–2411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hildebrandt F., Benzing T., Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1533–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]