Abstract

Understanding the evolution of virulence is key to appreciating the role specific loci play in pathogenicity. Streptomyces species are generally non-pathogenic soil saprophytes, yet within their genome we can find homologues of virulence loci. One example of this is the mammalian cell entry (mce) locus, which has been characterised in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. To investigate the role in Streptomyces we deleted the mce locus and studied its impact on cell survival, morphology and interaction with other soil organisms. Disruption of the mce cluster resulted in virulence towards amoebae (Acanthamoeba polyphaga) and reduced colonization of plant (Arabidopsis) models, indicating these genes may play an important role in Streptomyces survival in the environment. Our data suggest that loss of mce in Streptomyces spp. may have profound effects on survival in a competitive soil environment, and provides insight in to the evolution and selection of these genes as virulence factors in related pathogenic organisms.

Soil is a highly complex and competitive environment, in which interactions between multitudes of taxonomically diverse organisms occur. Evolutionary pressures in soil are high due to competition for resources, predation and continuously changing environments. Organisms with an ability to cope with these features have significant selective advantages over competitors. Gram-positive saprophytic soil bacteria from the genus Streptomyces have evolved many mechanisms that appear to offer competitive advantages in soil including the production of various small molecules, such as antibacterials, antifungals, and anti-helminthics1,2,3,4, restriction-modification systems to cope with viral attack5.

What is less clear is how streptomycetes cope with predation by eukaryotic soil organisms such as amoebae. However, the intrinsic mechanisms that allow soil organisms to interact with each other at the cellular and intracellular level are still poorly understood4. It is these mechanisms that may have led to the evolution of virulence traits in bacteria6. There has been much interest in the evolution of pathogenicity and how virulence factors in modern pathogens may have evolved through ancient interactions between bacteria and early eukaryotes. It seems likely that virulence mechanisms observed in pathogens are a coincidental product of selection in an unrelated host, with examples such as Legionella and Mycobacterium replicating in non-human environmental reservoirs7,8,9. It has also been suggested that because the evolution of true biological novelty is rare, virulence mechanisms have most likely evolved from the existing pool of genetic diversity. The main evidence supporting this hypothesis is the presence of virulence gene homologues in non-pathogens. One such locus is the mammalian cell entry (mce) gene cluster from Mycobacterium tuberculosis which is found in a variety of non-pathogenic actinomycetes10.

The mce operon was first identified in M. tuberculosis when a whole genome library was cloned into a non-invasive strain of Escherichia coli and a clone was found to confer the ability to invade non-phagocytic HeLa cells11. In addition, E. coli transformed with this clone were preferentially taken up and able to persist in macrophages11. Subsequent investigation of the M. tuberculosis genome revealed that there were four mce operons12. Mutational studies of the mce operons showed that knockouts are attenuated in mouse infection models13 yet hypervirulent in macrophage models14, presumably due to the presence of the complete immune system in whole animals15. The mce operons are expressed at different stages of infection, with mce1 expressed early during infection while mce4 is expressed more strongly after a number of weeks16,17.

Each mce operon encodes a core of two integral membrane proteins (YrbE1AB) and six putative secreted proteins (Mce1ABCDEF), which bear homology to ABC transporters and their substrate binding proteins10. The role of the mce4 locus was conclusively determined by Mohn et al., (2008), when it was shown that in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1, mce4 encodes an ATP-dependant steroid transporter providing the first direct evidence of transport activity. These authors also showed that mce4 activity was essential for growth on media containing a range of sterols as the sole carbon source. This suggests that the homologue of mce4 in Mycobacterium spp. may facilitate uptake and utilisation of cholesterol from host cells during infection, a function which is known to be essential for successful cellular invasion and persistence18,19 however there is significant divergence in amino acid sequence across the actinomycetes in the non-mce domains of the proteins, perhaps reflecting diversity in the substrate specificity.

Here we report the characterisation of the mce locus in the non-pathogenic soil saprophyte Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and how it influences interaction with other soil organisms. We show that the disruption of the mce cluster and characterisation of the mutants in amoebae and plant models, indicate these genes are likely to play a role in soil survival. In addition we report the regulation of these genes by the conserved two-component regulatory system MtrAB. Taken together these data suggest that loss of mce in Streptomyces spp. may have profound effects on survival in the soil environment, and provides insight in to the evolution and selection of the mce gene clusters as virulence factors in related pathogenic organisms.

Results

The Streptomyces coelicolor mce cluster

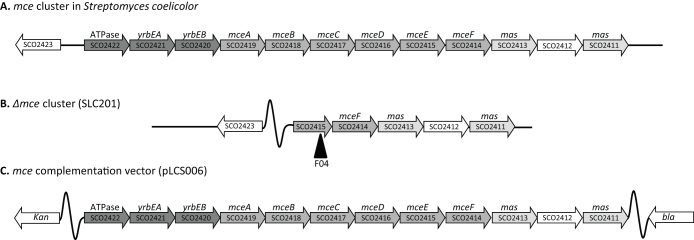

Analysis and annotation of the S. coelicolor genome identified a cluster of genes homologous to the mce (mammalian cell entry) cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis11,20. The cluster is 13.4 kb long and consists of nine core conserved genes, with two conserved mas (mce associated) genes in the downstream region, and one additional gene of unknown function10 (Fig. 1). In S. coelicolor the core ABC transporter ATP-binding domain-containing protein (SCO2422) and the putative ABC transporter integral membrane proteins (SCO2421 and SCO2420; 50.8 and 55.4% identity respectively with their M. tuberculosis homologues) correspond to products of the genes in M. tuberculosis annotated as yrbEA and yrbEB. The next six genes in the operon (SCO2419-SCO2414) encode proteins containing the Mce motif (Pfam family: PF02470; 33–37% identity with their M. tuberculosis homologues) and are annotated as mceABCDEF. The gene products contain a putative substrate-binding domain and are predicted to deliver substrates to the membrane component of the ABC transporter10. Comparison of the S. coelicolor cluster amongst published complete genomes of Streptomyces (4) indicates conservation of a single copy of the mce operon20,21,22. The exception to this is the plant pathogen S. scabies, which lacks the mce cluster (www.sanger.ac.uk; strepdb.streptomyces.org.uk/), whilst the genome of M. tuberculosis has four copies of the operon and the decayed genome of M. leprae has only a single copy12,23.

Figure 1.

(A) Organisation of the mce locus in Streptomyces coelicolor, including the SCO number designations (B) The genetic organisation of the Δmce strain (SLC201) and the Tn5062 (F04) insertion site (See materials and Methods) and (C) the organization of the complementation vector fragment in pLCS006.

The mce locus is constitutively expressed throughout growth on solid medium

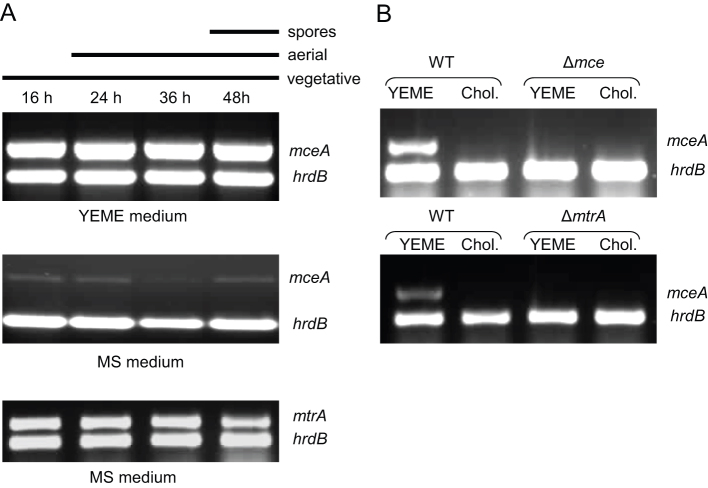

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR of the mce operon in S. coelicolor on solid YEME medium showed that the mce operon is highly expressed throughout the whole developmental life cycle relative to the multiplexed vegetative sigma factor hrdB, with no apparent developmentally linked transcriptional changes (Fig. 2.). The transcription of several mce genes was analysed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and the level of transcription was comparable to mceA, therefore mceA was considered to be representative of the operon. On MS medium, the mce operon is repressed relative to the multiplexed hrdB control (Fig. 2). Interestingly, soya flour contains high levels of sterols24, which suggests that high levels may repress expression of the mce genes. To test this hypothesis, RNA was isolated from S. coelicolor M145 and the mce null mutant grown for 36 hours on YEME medium and YEME medium supplemented with cholesterol (0.02 mg/ml). The addition of cholesterol to YEME medium repressed transcription of mceA (Fig. 2), suggesting that the mce cluster is only transcribed when low levels of sterols are available.

Figure 2.

(A) Transcriptional analysis of mce in Streptomyces coelicolor.RT-PCR of mceA, hrdB and mtrA during a developmental time course of S. coelicolor (M145) on solid YEME and MS media. The time points at which mycelium were harvested for RNA and the developmental stage of the culture was judged by microscopic examination and is indicated above. (B) Transcriptional analysis of mceA and hrdB on solid YEME with and without cholesterol in the wild-type (M145) and the ΔmtrA (SLC201) backgrounds.

mce in S. coelicolor is expressed in an mtrAB dependent manner

Nothing is known about the regulation of the mce gene cluster in Streptomyces spp. In Mycobacterium spp., the proximity of genes encoding GntR-like (mce1 and mce2) and TetR-like (mce3) regulators to the mce gene clusters gives some clues to their regulation25,26. In Streptomyces spp., however, there is no obvious regulatory gene adjacent to the mce gene cluster. In M. avium the mce genes are down regulated in an mtrB mutant (mtrB encodes the sensor kinase in the MtrAB two-component system27. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed transcription of mtrA in S. coelicolor is constitutive throughout growth relative to the vegetative sigma factor hrdB (Fig. 2). A mtrA null mutant was generated in order to determine whether MtrA modulates the transcription of the mce locus in S. coelicolor. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR showed that transcription of the mce locus was abolished in the ΔmtrA mutant, even in the absence of cholesterol, conditions which stimulated relatively strong transcription of the mceA in the WT strain (Fig. 2), suggesting that MtrA is required for expression of the mce genes in S. coelicolor.

Mutational analysis of the mce cluster in Streptomyces coelicolor

Given the roles played by the mce genes during M. tuberculosis infection, a complete mce cluster deletion mutant was created to interrogate the function of the mce cluster in S. coelicolor. Screening the mutant on a range of carbon sources (glucose, sucrose, mannitol, glycerol, galactose, lactose, arabinose, sorbitol, Tween 20, steric acid, oleic acid, palmitic acid (all 10 g/L), cholesterol (0.02 mg/ml) and sitosterol (0.02 mg/ml)) showed no difference in growth between WT and the mce mutant strain (data not shown). S. coelicolor A3(2) is unusual among bacteria in that it produces an agarase (DagA) enabling the hydrolysis of agar28. To ensure that agar utilisation did not mask an inability for the mce mutant to utilise test substrates, we generated a ΔdagA-Δmce strain and reanalysed the role of the mce locus in normal growth and differentiation. The ΔdagA−Δmce strains grew equally well as the parental strain M145 on solid and in liquid cultures (data not shown).

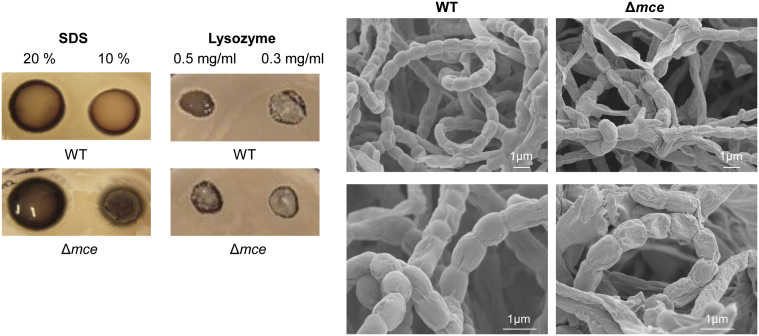

The response of these strains to various stress conditions was also investigated, including 2% ethanol, growth at 37°C and 40°C, 70°C, 1 M NaCl, beta-lactam (Carbenicillin 100 μg/ml) and aminoglycoside (Gentamicin and Neomycin, 20 μg/ml) antibiotics, however the mce mutants grew equally well as the WT strain under the conditions tested. Interestingly, the mce mutants were more tolerant to SDS (10% w/v) and lysozyme (0.5 mg/ml) than WT in plate spot assays (Fig. 3A), suggesting the cell envelope of the mce null mutant differed from that of the parental strain. To further investigate any possible defects in cell morphology, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed. SEM showed that spores produced by the mce mutant were wrinkled, more prone to collapsing and had abnormal appendages, indicative of spore germination on the spore chains (Fig. 3B). Analysis of the spore length also showed that the mean size of mutant spores was smaller (mean 0.7 μm +/− 0.05; n = 100) than WT (mean 0.9 μm +/− 0.05; n = 100).

Figure 3.

(A) Resistance of wild-type (M145) and Δmce mutant (SLC201) to SDS and lysozyme (concentrations indicated on figure).(B) Scanning Electron Microscopy of S. coelicolor wild-type (M145), and the Δmce mutant (SLC201). Bars indicate 1 μm.

A Streptomyces coelicolor mce mutant is virulent in an amoebae model

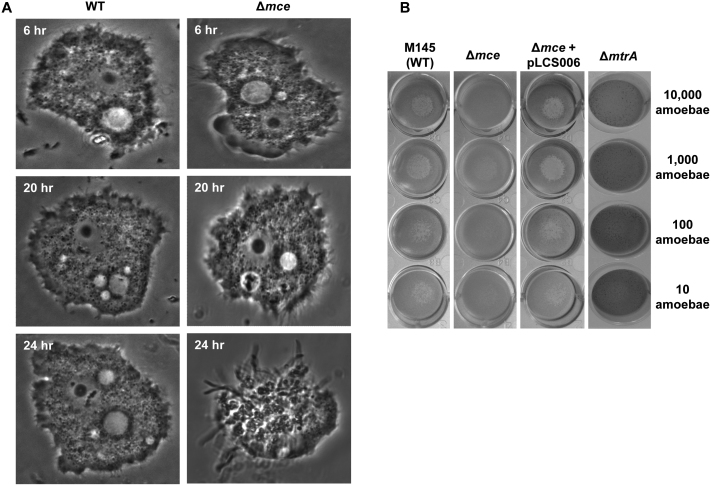

The mce cluster in Mycobacterium tuberculosis facilitates invasion and survival in macrophages11 and recently there has been significant interest in the use of amoebae as surrogate macrophages29. Amoebae are abundant soil microorganisms, which likely predate and feed on streptomycetes in the soil. Therefore we developed a co-culture and plaque assay for investigating the role of the mce gene cluster in S. coelicolor-amoebae interactions.

Introduction of S. coelicolor M145 spores to Acanthamoeba polyphaga in liquid co-culture experiments resulted in predation of the spores by A. polyphaga (Fig. 4A). Repeating the experiment with A. polyphaga and the mce null mutant resulted in rapid germination of the spores in the A. polyphaga vacuoles and death of the amoeba within 24 hrs (Fig. 4A). Using a trypan blue viability assay it was possible to assess the number of viable amoebae after 24 hours in co-culture with WT S. coelicolor as 78% +/− 5%, however in co-culture with the mce null mutant strain this was reduced to 52% +/− 3%. The virulence observed in an S. coelicolor mce mutant is not unprecedented, since an mce1 mutant of M. tuberculosis is hyper-virulent in a macrophage model14. Further screening of S. coelicolor-amoebae interactions was carried out using a modified plaque assay based on the method of Froquet et al.30, which allowed a range of strains and conditions to be tested in parallel. The results of the aqueous co-culture were replicated using the plaque assay. The mce mutant showed reduced plaque formation in comparison to the parent, indicating the amoebae were killed following predation of the mce mutant spores (Fig. 4B). The observed phenotype could be complemented by the addition of the complete mce cluster on the integrating vector pLCS006 (Fig. 1 & Fig. 4B). In support of these data, the mtrA mutant, which does not express the mce cluster, also displayed a virulence phenotype and behaved indistinguishably from the mce mutant (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, we tested several additional genes from S. coelicolor that are virulence related in actinomycete pathogens in the amoeba model (whiB31; and32; esxAB33; desD, as an example of a siderophore34, but no differences were observed when compared to the wild-type strain (Data not shown).

Figure 4.

(A) Co-culture experiments of S. coelicolor wild-type (M145) and Δmce mutant with Acanthamoeba polyphaga over 24 h.(B) Amoeba plaque assay of wild-type S. coelicolor (M145), the Δmce mutant (SLC201), the complemented Δmce mutant (SLC201 + pLCS006), and the ΔmtrA mutant. The figure shows the number of amoebae (right hand side of the figure) seeded on to lawns of S. coelicolor strains on a 50% dilution of nutrient agar to equalize the growth of the bacteria and amoebae (optimised according to the method of Froquet et al., 20083).

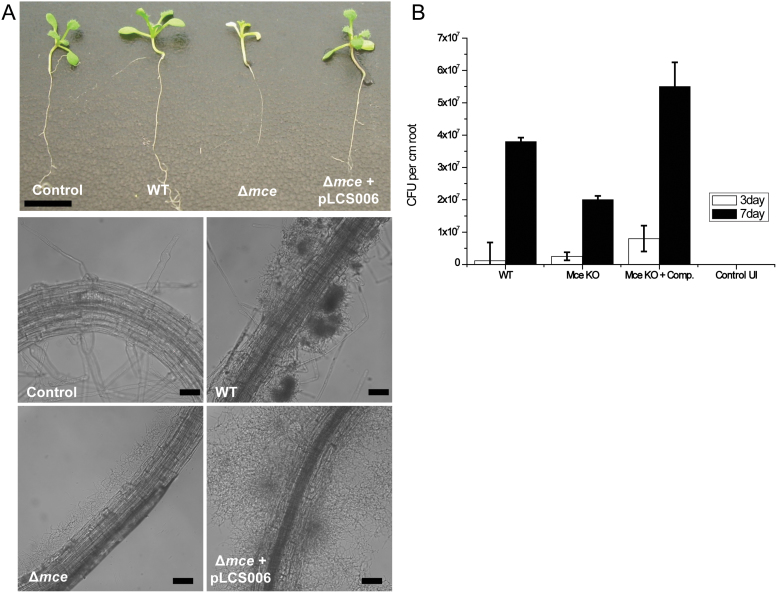

The Mce gene cluster is required for plant root colonisation

The likely substrate for the Rhodococcus and mycobacterial Mce proteins to import is sterols35. It is known that plants are a rich source of sterols such as sitosterol, stigmasterol and campersterol36. Given this rich source of phytosterols and the abundance of Streptomyces spp. in the soil37, it is possible that the mce cluster aides the survival of streptomycetes in the rhizosphere by increasing access to soil resources. The role of the Mce importer was investigated in root colonisation assays using Arabidopsis thaliana Ecovar Columbia CL295 as a model. Plants inoculated with spores of S. coelicolor M145 grew normally, with uniform colonisation of the roots and bacterial numbers increased over a 7 day period (Fig. 5A & B). Plants inoculated with spores of the mce null mutant SLC201 showed reduced growth compared to WT inoculated plants and colonisation levels of the roots was also reduced (Fig. 5A & B). This phenotype could be recovered by complementation of the mce mutant with pLCS006 (Fig. 5A & B).

Figure 5. Colonisation of Arabidopsis roots by wild-type S. coelicolor (M145), the Δmce mutant (SLC201), the complemented mce mutant (Δmce + pLCS006) showing whole plants and microscopy of roots (A) and colony counts of colonised roots at 3 and 7 days post inoculation.

Error bars represent the standard deviation of 3 replicates from 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

This study investigated the function of a known pathogenicity locus in the non-pathogenic soil actinomycete S. coelicolor through mutagenesis and screening under a range of conditions. The mce locus was not required for growth on a range of carbon substrates and mce mutants were not altered in a range of tests against deleterious agents, except for an increased resistance to lysozyme and SDS in the mce null mutant compared to wild-type S. coelicolor. It has recently been shown in some Rhodococcus spp. that the mce loci encode ABC-like importer systems10,35, and it is possible that the reduction in the number of transporters/porins may stabilise the cell envelope and result in increased resistance to SDS (membrane) and lysozyme (cell wall) stressors. Scanning electron microscopy also indicated changes to the spore surface in the mce mutant, as its spores were more wrinkled in appearance than those of the parent and in addition showed premature germination. Interestingly, such precocious germination has also been observed in mutants lacking the chitobiose transporter sugar binding protein DasA38, as well as in other S. coelicolor mutants with defective cell envelopes, including an lsp (lipoprotein signal peptidase) mutant which is defective in lipoprotein biogenesis39. In mycobacteria, Cangelosi et al.27, noted that the mtrA mutants of M. avium have defective cell walls and given that the mce gene clusters in both S. coelicolor and Mycobacterium spp. are down regulated in mtrAB mutants, this indicates some commonality in the regulons of the MtrAB two-component system within the actinomycetes, which is not surprising because the MtrAB two-component system, and its accessory lipoprotein LpqB, are highly conserved in actinomycetes40.

Amoebae are often used as surrogate macrophages for infection studies29 and streptomycetes are likely to encounter and be predated by amoebae in their natural soil environment. The mce locus is required for intracellular survival in macrophages in M. tuberculosis11, therefore we hypothesised that wild-type and mce mutant strains of S. coelicolor might behave differently in an amoeba model. We were able to observed predation of Streptomyces coelicolor spores by A. polyphaga in both the plaque assay and co-culture experiments. Intriguingly, this study shows that a S. coelicolor mce mutant has a virulent phenotype against A. polyphaga, with the spores germinating and resulting in the death of amoebae. This is in stark contrast to WT S. coelicolor, which is predated successfully by A. polyphaga (Fig. 4A). The virulence phenotype observed in S. coelicolor mce is not unprecedented since an mce1 mutant of M. tuberculosis is hypervirulent in a range of models, most likely due to more rapid growth in the host14,15. The reason for S. coelicolor mce null mutant virulence is not yet fully understood, but they clearly survived predation better than wild-type strains when tested in two separate amoeba models. Two key phenotypic differences may contribute to this; the precocious germination phenotype and increased survival in the phagosome due to increased lysozyme resistance. Growth of the S. coelicolor Δmce mutant was impaired, however, in plant root colonisation assays, suggesting that the ability to utilise the multitude of nutrient sources from plant root exudates is a selective advantage in the rhizosphere, perhaps representing two conflicting selective pressures for streptomycetes in soil. Streptomyces spp. are well established as rhizosphere bacteria, where they likely offer protection to plant roots against fungal infection4,37. Plants are known to be a major source of sterols, sugars, polysaccharides, amino acids, and fatty acids in the environment41,42 and offer a significant resource in the rhizosphere, suggesting they may form a mutually beneficial protective symbiosis with plant roots. Whilst the only known substrate for the Mce transporters is sterols, from the work of Mohn et al.35, the duplication and diversification of these mce clusters in certain actinomycetes (such as rhodococci and mycobacteria) may have lead to the organisms increasing the repertoire and diversity of substrates transported by Mce. In pathogens the ability to utilise abundant host carbon sources such as sterols for intracellular growth during infection or persistence would be a significant selective trait35. In Streptomyces spp. we do not know the nature of the substrates transported by the mce cluster, however based on homology we predict that its substrates would be similar to the sterols transported by the mycobacterial Mce transporters. Transcription of the mce was reduced in medium containing sterol, suggesting that higher levels of sterols repress mce gene expression. However it is possible that with six substrate-binding proteins (encoded by mceABCDEF) the Mce transporter may be responsible for transporting multiple substrates, perhaps of a related chemical nature.

Examining regulation of the mce genes in S. coelicolor revealed that it is part of the MtrAB regulon, indicating that there is at least some overlap in the genes regulated by MtrA in different actinomycete genera. This two-component system is relatively poorly understood, but appears to regulate some essential processes in actinomycete growth (cell wall remodelling and cell division), survival and pathogenicity27,40,43,44. Intriguingly the mce cluster has been lost from the plant pathogen, S. scabies, which maybe due to the presence of additional plant specific virulence factors, providing a route to plant derived nutrients45.

The evolution of virulence almost certainly draws on existing pools of genetic diversity and novel functions are achieved through selection and alterations in regulation, leading to the co-option of genes for roles in pathogenicity. Here we have shown that the mce locus in the non-pathogenic S. coelicolor has functions that mediate interaction of these organisms with plants and amoebae, suggesting that these genes are important in the soil environment. This locus however is a known virulence factor for the human pathogen, M. tuberculosis. The evolution of this locus, through duplication and divergence (M. tuberculosis has four copies of the mce operon) has almost certainly contributed to virulence in mycobacteria. The presence of these genes across the actinomycete lineage10 and the standard G+C content of the mce genes in each organism (Clark and Hoskisson, unpublished) suggest that this locus is ancient in the actinomycete lineage. We therefore hypothesise that the mce locus was present in the ancient actinomycete lineage (streptomycetes split from the main lineage approximately 440 million years ago)46; and niche specialization (soil in Streptomyces spp., or soil and ultimately eukaryotic hosts in mycobacteria) has lead to divergence of the respective clusters in each actinomycete genus throughout evolution. Understanding the selection that leads to these changes in function are key to our appreciation of the evolution of virulence in bacteria and could have a profound impact on our understanding of the emergence of pathogenic strains.

Methods

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

The strains of S. coelicolor A3(2) and its derivatives used are summarised in Table 1. All strains were cultivated at 30°C on mannitol-soya flour (MS) agar47 or solid YEME medium containing 0.02 mg/ml cholesterol as indicated28. Conjugation of plasmids from the E. coli strain ET12567 (dam− dcm− hsdS), which contained the plasmid pUZ8002 as a driver for transfer48. Acanthamoeba polyphaga was maintained on peptone yeast glucose (PYG) medium in 25 ml tissue culture flasks at 20°C49.

Table 1. Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype/comments | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | ||

| M145 | Prototrophic, SCP1− SCP2− | Kieser et al., 2000 |

| SLC201 | M145 derivative with a deletion of the mce operon (see Fig. 1.) | This work |

| ΔmtrA | M145 ΔmtrA::apr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ10702 | Cosmid backbone replacement integrating at phage φC31 attB site. | Foulston and Bibb, 2010 |

| pNRT4 | Kanamycin (aphII) containing E coli shuttle vector | Herron, University of Strathclyde, Unpublished |

| pLC006 | Cosmid 8A2 digested to 22 kbp, with the Supercos1 backbone swopped with pIJ10702 and pNRT4 ligated to confer kanamycin resistance for counter selection. | This work |

Construction of a mce cluster deletion mutant and complementation

A derivative of cosmid 8A250 carrying a Tn5062 insertion in SCO2415 (8A2.1.F04; provided by Dr Lorena Fernández-Martínez and Professor Paul Dyson) was used to generate an mce cluster deletion mutant based on the in vitro transposition method51. Construction of the mce cluster deletion mutant was achieved through partial digest of cosmid 8A2.1.F04 using BamHI to excise the region between and including SCO2422 and SCO2415, but retaining the Tn5062 insertion in SCO2415, resulting in the formation of cosmid pLCS001. This cosmid was subsequently introduced into S. coelicolor M145, by conjugation from E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002. Mutants exhibiting the double-crossover phenotype (apramycin resistant, kanamycin sensitive) were confirmed by Southern hybridisation, creating strain SLC201 (Δmce cluster).

The complementation vector pLCS006 was constructed using cosmid 8A2.2.G07, which contains a Tn5062 insertion in SCO2423 (a gene adjacent to the mce cluster). Partial digestion with KpnI, followed by partial digestion with EcoRI and self re-ligation, resulted in the excision of sections of the cosmid insert not containing the mce genes. The resulting cosmid was reduced from 50.1 kb to 22.3 kb while maintaining the supercos1 backbone and associated antibiotic resistance markers. To create an single copy integrating vector for complementation, this cosmid was then used to transform hyper-recombinant E. coli strain BW25113/pIJ790 along with a 5247 bp SspI fragment of plasmid pIJ10702 (a gift from Prof Mervyn Bibb and Dr Lucy Foulston, John Innes, UK) containing ϕC31 integrase and attP site52. The resulting recombinant plasmid was digested and ligated with plasmid pNRT4 (provided by P. R. Herron, University of Strathclyde) that contains a kanamycin resistance gene (aphII) to facilitate selection in apramycin resistant strains. The resulting cosmid derivative (pLCS006) was introduced into ET12567/pUZ8002 and introduced into S. coelicolor mce mutant strains by conjugation.

Generation of an mtrA mutant strain

The mtrA (SCO3013) null mutant was created by PCR-targeted mutagenesis53. A disruption cassette consisting of an oriT and the apramycin resistance gene, aac(3)IV from pIJ77353 was generated by PCR amplification with primers SCO3013KOF (5′-GTGCCAGGTCACGCCAGGTAACGATTAGCTAATGGGATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′) and SCO3013KOR (5′-GACCCGGGCGCCGAAGCGGCACTGTCCCTGGCCATGTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′) that included the start or stop codons of mtrA and 36 nt sequence homologous to the upstream or downstream sequence of the mtrA open reading frame. The resulting PCR product was used to mutagenize S. coelicolor cosmid StE33 as previously described53. Mutagenized cosmid was verified by restriction digest and introduced into E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 and conjugated into S. coelicolor M145 as previously described28. Transconjugants were selected for resistance to apramycin and sensitivity to kanamycin. The integrity of the mtrA mutant strain was verified by PCR using primers RFS16 (5′-GCTATCCGCTCGCGGTG-3′) and RFS17 (5′-GAAGAGACGGGAGCCGAC-3′).

Amoeba assays

Amoeba-bacteria co-culture assay

Acanthamoeba polyphaga cultures were grown to log phase (3–5 days) in PYG at 20°C and cells were harvested by centrifugation (500 × g for 3 minutes). Cells were re-suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and live cell titres (assessed by trypan blue exclusion) were adjusted to the required number of cells. The amoebae and spores of S. coelicolor were combined in a 24-well plate at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:1 or 1:10, with approximately 1 × 105 number of microorganisms per well. Plates were incubated at 21°C, with cells harvested for microscopy at the indicated time intervals.

Phagocytic plaque assay of amoebae killing

The method of Froquet et al.30, was adapted for analysing the interaction between A. polyphaga and S. coelicolor. Aliquots (0.75 ml) of nutrient agar in varying concentrations (Nutrient broth at 100–10% of the manufacturer's recommended concentration with 15 gl−1 bacteriological agar; which allows for equalisation of the growth of the bacteria with the amoebae) were placed in each well of a 24-well plate and dried in a laminar flow hood. S. coelicolor spores were diluted to 108 spores/ml with PBS and 50 μl the diluted suspensions were transferred to the surface of the agar and allowed to dry; this ensures a confluent lawn of bacterial growth. Amoebae cells were harvested as described above and diluted to a concentration of 200 × 104, 20 × 104, 2 × 104 or 0.2 × 104 live cells per ml with PBS. Amoebae suspension (5 μl) was dispensed into the centre of each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 2–5 days and observed daily for signs of plaque formation.

Plant Cultivation and root colonisation assays

Root colonisation assays were performed using Arabidopsis thaliana (Ecovar Columbia CL295). Seeds were surface sterilized (15% sodium hypochlorite solution for 15 minutes), washed in sterile distilled water and germinated on Murashige and Skoog agar medium supplemented with 2% sucrose in Petri dishes54. Plants were grown at 21°C with a 16-h photoperiod for seven days. Plants for colonization experiments were transferred to Magenta boxes (8 plants per box; Sigma), containing Murashige and Skoog agar medium as above and allowed to equilibrate for 24 hrs on the surface of the medium before inoculation. This allowed the plant roots to be separated more easily for colony counting. Plants roots were inoculated with S. coelicolor strains (1 × 106 spores) or mock-inoculated with sterile 20% glycerol. Plants were harvested 3 days and 7 days and colonization of plant roots was assessed by microscopy.

To enumerate bacterial colonization, 1 cm sections of root were removed under sterile conditions and homogenized in 500 μl sterile distilled water, serially diluted and counted by plating on to nutrient agar (Difco).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR of the mce and mtrA genes

RNA samples were isolated throughout the lifecycle of wild-type and mutant strains of S. coelicolor as previously described55. Aliquots (50 μg) of DNase-treated RNA were reverse transcribed and immediately subjected to 25 cycles of PCR amplification using the One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Control reactions in which reverse transcriptase was omitted were also performed. The following primers were used for amplification of mceA (forward 5′-TCCGACCCGGTGGTCGTCGAGA-3′; Reverse 5′-GTGAAGTCGGTGAGCGCCGTGA-3′), mtrA (forward 5′- GACACCGCACTGGCCGAGA -3′; Reverse 5′- GTAGCCCCAGACCTGCTCGA -3′) and the vegetative sigma factor hrdB was used as a control in a multiplex PCR for constitutive expression and amplification using the following primers (forward 5′-GAGGCGACCGAGGAGCCGAA-3′; Reverse 5′-GCGGAGGTTGGCCTCCAGCA-3′).

Microscopy

Light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy were performed as described previously56.

Author Contributions

L.C.C. and P.A.H. conceived the study and carried out experimental work with contributions from P.P., J.W., R.F.S., M.I.H., G.P.W.; L.C.C. and P.A.H. wrote the manuscript with contributions from P.P., J.W., R.F.S., M.I.H., G.P.W.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Supporting data showing the effect of dilution of nutrient agar on the equalization of growth of the amoebae and Streptomyces

Acknowledgments

LCC was funded by a PhD scholarship from University of Strathclyde. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Society for General Microbiology for a Presidents Fund grant to PAH to undertake work at the Instituto de Agricultura Sostenible, Córdoba, Spain. MIH acknowledges financial support from the Royal Society and the University of East Anglia to work on MtrAB and RFS is supported by MRC grant G0801721. We would also like to thank Dr Maria Sanchez-Contreras, Prof Paul Dyson, Prof Mark Buttner, Dr Paul Herron and Dr Paco Baron-Gomez for strains/plasmids. We would also like to thank Michael Ambrose, John Innes Centre, for contributing the Arabidopsis seeds. We thank Vartul Sangal for helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Challis G. L. & Hopwood D. A. Synergy and contingency as driving forces for the evolution of multiple secondary metabolite production by Streptomyces species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14555–14561 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater K. F., Biró S., Lee K. J., Palmer T. & Schrempf H. The complex extracellular biology of Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 34, 171–198 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel G. P. & McDowall K. J. The regulation of the secondary metabolism of Streptomyces: new links and experimental advances. Nat Prod Rep 28, 1311–1333 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipke R. F., Kaltenpoth M. & Hutchings M. I. Streptomyces as symbionts: an emerging and widespread theme? FEMS Microbiology Reviews 36, 862–876 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson P. A. & Smith M. C. M. Hypervariation and phase variation in the bacteriophage ‘resistome’. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 396–400 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, B. R. & Svanborg Eden, C. Selection and evolution of virulence in bacteria: an ecumenical excursion and modest suggestion. Parasitology 100, 1–13 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V. & Greub G. Amoeba/Amoebal Symbiont Genetic Transfers: Lessons from Giant Virus Neighbours. Intervirology 53, 254–267 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moliner C., Fournier P.-E. & Raoult D. Genome analysis of microorganisms living in amoebae reveals a melting pot of evolution. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 34, 281–294 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoth F. & Greub G. Amoebal pathogens as emerging causal agents of pneumonia. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 34, 260–280 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali N. & Riley L. W. A phylogenomic analysis of the Actinomycetales mce operons. BMC Genomics 8 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda S., Bomfim G., Knights R., Huima-Byron T. & Riley L. W. Cloning of an M. tuberculosis DNA fragment associated with entry and survival inside cells. Science 261, 1454–1457 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393, 537–544 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioffré A. et al. Mutation in mce operons attenuates Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Microbes and Infection 7, 325–334 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono N. et al. Hypervirulent mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resulting from disruption of the mce1 operon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15918–15923 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokum t. e. n., A M. C., Movahedzadeh F., Frita R., Bancroft G. J. & Stoker N. G. The case for hypervirulence through gene deletion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 16, 436–441 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S. M. et al. Characterization of mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11760–11765 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnappinger D. et al. Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights in to the phagosomal environment. The Journal of Experimental medicine 198, 693–704 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters J. & Gatfield J. Hijacking the host: survival of pathogenic mycobacteria inside macrophages. Trends Microbiol. 10, 142–146 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Chastellier C. & Thilo L. Cholesterol depletion in Mycobacterium avium-infected macrophages overcomes the block in phagosome maturation and leads to the reversible sequestration of viable mycobacteria in phagolysosome-derived autophagic vacuoles. Cell Microbiol 8, 242–256 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley S. D. et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417, 141–147 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura S. et al. Genome sequence of an industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis: deducing the ability of producing secondary metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12215–12220 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi Y. et al. Genome Sequence of the Streptomycin-Producing Microorganism Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350. J. Bacteriol. 190, 4050–4060 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T. et al. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409, 1007–1011 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agater I. B. & Llewellyn J. W. Determination of β-sitosterol in meats, soya and other protein products. Food Chemistry 8, 43–49 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- la Paz Santangelo d. e., M. et al. Mce2R from Mycobacterium tuberculosis represses the expression of the mce2 operon. Tuberculosis 89, 22–28 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo M. D. L. P. et al. Mce3R, a TetR-type transcriptional repressor, controls the expression of a regulon involved in lipid metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 155, 2245–2255 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi G. A. et al. The two-component regulatory system mtrAB is required for morphotypic multidrug resistance in Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 50, 461–468 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T., Bibb M. J., Buttner M. J., Chater K. F. & Hopwood D. A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. John Innes Foundation (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Cosson P. & Soldati T. Eat, kill or die: when amoeba meets bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 271–276 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froquet R., Lelong E., Marchetti A. & Cosson P. Dictyostelium discoideum: a model host to measure bacterial virulence. Nat Protoc 4, 25–30 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater K. F. & Chandra G. The evolution of development in Streptomyces analysed by genome comparisons. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 30, 651–672 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiman D. E., Raghunand T. R., Agarwal N. & Bishai W. R. Differential Gene Expression in Response to Exposure to Antimycobacterial Agents and Other Stress Conditions among Seven Mycobacterium tuberculosis whiB-Like Genes. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 50, 2836–2841 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akpe San Roman S. et al. A heterodimer of EsxA and EsxB is involved in sporulation and is secreted by a type VII secretion system in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology 156, 1719–1729 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barona-Gómez F., Wong U., Giannakopulos A. E., Derrick P. J. & Challis G. L. Identification of a Cluster of Genes that Directs Desferrioxamine Biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 16282–16283 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn W. W. et al. The actinobacterial mce4 locus encodes a steroid transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35368–35374 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlík M., Pavlíková D., Balík J. & Neuberg M. The contents of amino acids and sterols in maize plants growing under different nitrogen conditions. Plant Soil Environ 56, 125–132 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Tokala R. K. et al. Novel plant-microbe rhizosphere interaction involving Streptomyces lydicus WYEC108 and the pea plant (Pisum sativum). Applied and Environmental Microbiology 68, 2161–2171 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson S. et al. The chitobiose-binding protein, DasA, acts as a link between chitin utilization and morphogenesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology 154, 373–382 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. J. et al. Investigating lipoprotein biogenesis and function in the model Gram-positive bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor. Molecular Microbiology 77, 943–957 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson P. A. & Hutchings M. I. MtrAB–LpqB: a conserved three-component system in actinobacteria? Trends Microbiol. 14, 444–449 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin C., Yang X. & Weston L. The role of root exudates and allelochemicals in the rhizosphere. Plant Soil 256, 67–83 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Romheld V. & G N. Root-induced changes in the ability of nutrients in the rhizosphere. Plant Roots–the Hidden Half 617–649 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Moker N., Kramer J., Unden G., Kramer R. & Morbach S. In Vitro Analysis of the Two-Component System MtrB-MtrA from Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3645–3649 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fol M. et al. Modulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proliferation by MtrA, an essential two-component response regulator. Molecular Microbiology 60, 643–657 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loria R., Kers J. & Joshi M. Evolution of plant pathogenicity in Streptomyces. Ann Rev Phytopathol 44, 469–487 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman D. et al. Molecular evidence for the early colonization of land by fungi and plants. Science 293, 1129–1133 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs G., Frazer C., Gardner D. J., Cullum J. & Oliver S. Dispersed growth of Streptomyces in liquid culture. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 31 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Bierman M. et al. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116, 43–49 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterfield N. R. et al. Rapid Virulence Annotation (RVA): identification of virulence factors using a bacterial genome library and multiple invertebrate hosts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 15967–15972 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redenbach M. et al. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Molecular Microbiology 21, 77–96 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop A., Fielding S., Dyson P. & Herron P. Systematic insertional mutagenesis of a streptomycete genome: a link between osmoadaptation and antibiotic production. Genome Res. 14, 893–900 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulston L. C. & Bibb M. J. Microbisporicin gene cluster reveals unusual features of lantibiotic biosynthesis in actinomycetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 13461–13466 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust B., Challis G. L., Fowler K., Kieser T. & Chater K. F. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1541–1546 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T. & Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson P. A., Rigali S., Fowler K., Findlay K. C. & Buttner M. J. DevA, a GntR-like transcriptional regulator required for development in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5014–5023 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse J., Borst J. W., de Waal E., Bisseling T. & van Wezel G. P. Positive control of cell division: FtsZ is recruited by SsgB during sporulation of Streptomyces. Genes & Development 25, 89–99 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Supporting data showing the effect of dilution of nutrient agar on the equalization of growth of the amoebae and Streptomyces