Abstract

Background

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) expansion is common during the first 24 hours after onset, but the pattern and pace of hyperacute hemorrhage growth have not been described because serial imaging is typically performed over the course of hours and days, not minutes. The purpose of this study is to elucidate the spatial and temporal characteristics of hyperacute hemorrhage expansion within minutes of ICH onset.

Methods

An 86-year-old man with probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy developed an ICH while in the MRI scanner. Hyperacute hemorrhage growth was captured at three time points over a 14-minute interval of MRI data acquisition and at a fourth time point with CT 22 hours later. MRI and CT datasets were spatially coregistered, and three-dimensional models of ICH expansion were generated.

Results

Longitudinal analysis revealed that the spatial pattern of ICH growth was asymmetric at each time point. Maximal expansion occurred along the anterior-posterior plane during the first four minutes but along the superior-inferior plane during the next 10 minutes. The temporal pace of ICH expansion was also non-uniform, as growth along the anterior-posterior plane outpaced medial-lateral growth during the first 4 minutes (2.8 cm vs. 2.5 cm), but medial-lateral growth outpaced anterior-posterior growth over the next 10 minutes (1.0 cm vs. 0.2 cm).

Conclusions

We provide evidence for asymmetric, non-uniform expansion of a hyperacute hemorrhage. These serial imaging observations suggest that hemorrhage expansion may be caused by local cascades of secondary vessel rupture as opposed to ongoing bleeding from a single ruptured vessel.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, MRI, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral microbleed

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) expansion is common during the first 24 hours after onset and is associated with clinical deterioration and increased risk of death [1-3]. The pathophysiological basis of ICH expansion is unknown. ICH growth may result directly from continued bleeding by the initially ruptured vessel. An alternative possibility is that expansion occurs via secondary mechanical disruption of arterioles near the site of primary vessel rupture, as described in C. Miller Fisher's classical histopathological analysis of hypertensive hemorrhage [4]. Current knowledge about in vivo ICH expansion is limited, however, coming from serial neuroimaging studies performed over hours to days [1]. Hyperacute ICH onset and evolution have only rarely been captured with neuroimaging within minutes of ictus in humans [5]. In this report, we analyzed the spatial and temporal characteristics of hyperacute hemorrhage growth with sequential MRI data obtained over a span of 14 minutes, providing new insights into the pattern and pace of hyperacute ICH expansion.

Methods

Case Presentation

An 86-year-old left-handed man with prior right temporoparietal hemorrhage and multiple cerebral microbleeds, meeting clinical criteria for probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) [6], was brought to the hospital by his family because of 48 hours of progressive confusion, word-finding difficulty, and headache. He had a history of mild memory difficulties but performed all activities of daily living and could complete crossword puzzles. He was on no antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications. At the time of admission, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Neurological examination was notable for inattention, perseveration, non-fluent speech and difficulty following multistep commands. Laboratory evaluation of serum and urine was normal. Initial head CT scan showed encephalomalacia in the right temporoparietal region from the prior hemorrhage and generalized cortical atrophy with a parietal predominance, but no acute abnormality. Electroencephalography (EEG) demonstrated no evidence of epileptiform activity, generalized encephalopathy, or post-ictal state.

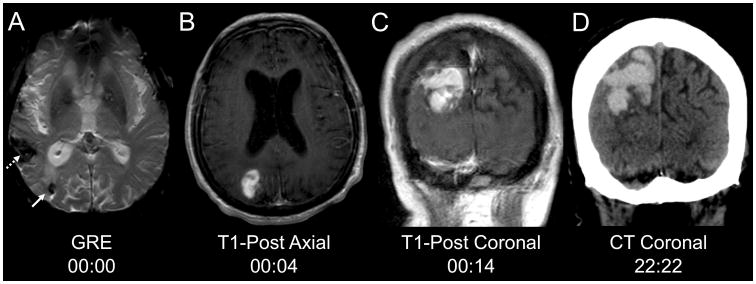

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on hospital day 2, and an evolution of signal changes was noted on consecutive sequences. The gradient-recalled echo (GRE) sequence performed at the beginning of the scan revealed a right parietal cerebral microbleed (CMB) that was new since an MRI performed two years prior (Fig. 1a). Two minutes after the GRE sequence, a T1 pre-contrast (T1-pre) sequence demonstrated no evidence of macrohemorrhage in the region of this CMB. Two minutes later, gadolinium was administered and a T1 post-contrast axial sequence (T1-post axial) revealed an 8.8 cc enhancing lesion in the right parietal lobe, adjacent to the CMB (Fig. 1b). Ten minutes later, a T1 post-contrast coronal sequence (T1-post coronal) revealed expansion of this enhancing lesion to 20.5 cc (Fig. 1c). After the MRI scan, the patient's neurological examination was notable for new left-sided hemineglect. Repeat head CT 22 hours and 22 minutes after the MRI demonstrated a large right parietal hyperdensity (Fig. 1d), representing further hemorrhage expansion to 43.5 cc despite aggressive blood pressure control in a neurological intensive care unit. The patient was eventually discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility, with mild improvement in his non-fluent aphasia and neglect. Of note, hemorrhage volume was calculated at each time point using the “ABC/2” method [7].

Fig. 1.

Hyperacute hemorrhage onset and expansion. a The chronic right temporoparietal hemorrhage (dotted arrow) and a new (since an MRI two years prior) right parietal microbleed (solid arrow) are seen on MRI gradient-recalled echo (GRE) sequence. b Four minutes later, contrast extravasation is present on the T1-post axial sequence. c Ten minutes later, the region of contrast extravasation has expanded on the T1-post coronal sequence. d A computed tomography scan 22 hours and 22 minutes after the GRE sequence demonstrates a large right parietal hyperdense lesion, consistent with hemorrhage.

Image Processing and Analysis

Imaging data from the patient's MRI (GRE, T1-post axial, and T1-post coronal) and his follow-up CT were coregistered to anatomic images from the patient's T1-pre axial dataset using FMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT version 5.5) in the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) [8], with a rigid-body 3-dimensional transformation employing 6 degrees of freedom. Intramodality coregistrations of MRI data were performed using a correlation ratio cost function. The intermodality CT-to-MRI coregistration was performed using a mutual information cost function [9]. Neuroanatomic accuracy of all coregistration procedures was confirmed by co-localization of landmarks in the anterior, middle, and posterior fossae. To optimize the accuracy of the GRE-to-T1-pre coregistration, the brain was extracted from the skull in both datasets using the Brain Extraction Tool in FSL [8]. After coregistration, CMB and macrohemorrhage outlines were manually traced on each dataset using Trackvis version 5.2 [10]. All hemorrhage tracings were rendered in 3-dimensions and superimposed on the T1-pre axial dataset for longitudinal comparative analysis.

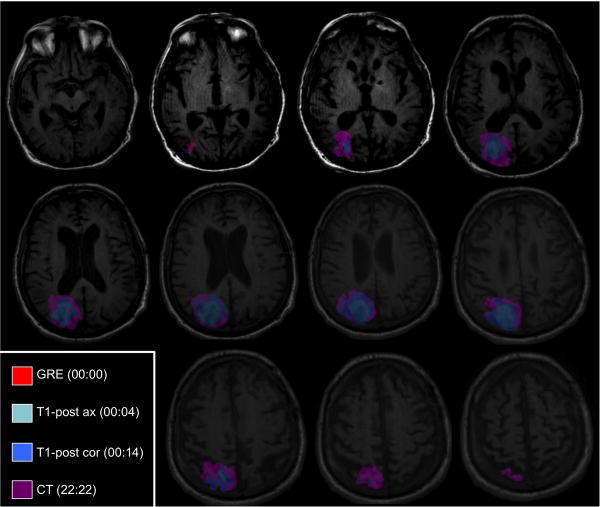

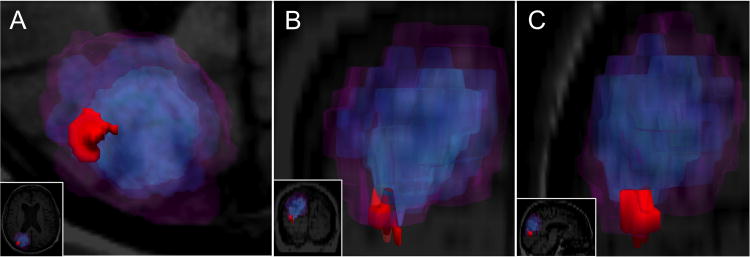

Results

Although the exact timing and spatial localization of hemorrhage onset cannot be definitively determined, we defined the timeline for hemorrhage expansion as starting at the GRE sequence (00:00 [hours:minutes]), because the CMB was new since a prior MRI scan and located at the macrobleed's inferolateral border. Hemorrhage volume expanded from 8.8 cc (00:04) to 20.5 cc (00:14) to 43.5 cc (22:22) (Table 1). At each time point, the hemorrhage was asymmetrically shaped, with finger-like projections that corresponded to the gyral topography of the posterior frontal and parietal lobes (Fig. 2). At the last time point (22:22), the hemorrhage appeared more spherically shaped (Fig. 3), although the superior and inferior margins of the hemorrhage conformed to the local gyral topography. The pace of hemorrhage expansion was larger in the anterior-posterior (A-P) plane than in the medial-lateral (M-L) and superior-inferior (S-I) planes over the first 4 minutes, but the rate of expansion in the superior-inferior (S-I) plane was then maximal at each subsequent time point (Table 1). Although the rate of expansion along the A-P axis slightly outpaced M-L growth in the first 4 minutes (2.8 cm vs. 2.5 cm), over the next 10 minutes M-L growth (1.0 cm; 40%) substantially exceeded A-P growth (0.2 cm; 7.1%). Similar variability was observed between 00:14 and 22:22, during which acceleration of ICH expansion in the A-P-plane (from 7.1% growth over the prior 10 minutes to 33.3% growth) was accompanied by deceleration of ICH expansion in the M-L plane (from 40.0% growth over the prior 10 minutes to 17.1% growth). Longitudinal hemorrhage expansion can be viewed in the Supplementary Video.

Table 1. Expansion of Hemorrhage Diameter and Volume.

| Time | Imaging Modality | Anterior-Posterior | Medial-Lateral | Superior-Inferior | Volume | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (cm) | % Expansion | Diameter (cm) | % Expansion | Diameter (cm) | % Expansion | Total (cc) | % Expansion | ||

| 00:04 | T1-Post Axial | 2.8 | N/A | 2.5 | N/A | 2.5 | N/A | 8.8 | N/A |

| 00:14 | T1-Post Coronal | 3.0 | 7.1% | 3.5 | 40.0% | 3.9 | 56.0% | 20.5 | 133.0% |

| 22:22 | CT | 4.0 | 33.3% | 4.1 | 17.1% | 5.3 | 35.9% | 43.5 | 112.2% |

Time is provided in hours:minutes format, with 00:00 defined as the time of gradient-recalled echo data acquisition. Calculations of % hemorrhage expansion at 00:14 and 22:22 were performed by comparing the diameter and volume measurements to the corresponding measurements from the prior time point. For the diameter calculations, the maximal diameter of the hemorrhage was measured in each plane.

Fig. 2.

Hyperacute hemorrhage expansion in the axial plane at sequential time points. Gradient-recalled echo (GRE), T1-post axial (T1-post ax), T1-post coronal (T1-post cor), and computed tomography (CT) imaging data are all coregistered to the T1-pre axial imaging dataset. The hemorrhage was manually outlined on each coregistered dataset, and the outlines are superimposed here on the T1-pre axial dataset. The shape of the hemorrhage changes at each time point, and hemorrhage expansion in anterior-posterior and medial-lateral planes is asymmetric on each axial image.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional models of hemorrhage expansion at each time point. a-c Hemorrhage expansion is shown in the axial (a), coronal (b) and sagittal (c) planes. Each panel provides a zoomed view of the hemorrhage, with full views provided as insets for reference. Color-coding of the microbleed and the macrobleed at each time point are the same as in Fig. 2.

Discussion

The imaging findings in this case provide a unique glimpse of hyperacute hemorrhage onset and evolution in vivo. Our longitudinal analyses of coregistered imaging datasets offer intriguing support for the possibility that hyperacute hemorrhage expansion occurs asymmetrically and with marked variability in both space and time. Mechanistically, asymmetric expansion may be partly explained by local differences in tissue barriers to ICH growth or by the directional orientation of a jet of blood escaping from the site of primary vessel rupture [11], but neither of these mechanisms sufficiently explains the significant spatial and temporal variability in preferential directions of growth that were observed in this case. Rather, our observations support a model of hemorrhage expansion in which asymmetric growth is determined in part by local cascades of secondary vessel rupture [4]. Bursts of local hemorrhage growth could result from a random “avalanche” of rupture events occurring in particular regions of the expanding hemorrhage, a finding also demonstrated by a computer simulation of the secondary rupture model [12]. An alternative possibility is that asymmetric growth could be driven by anatomic clusters of severely diseased small vessels that are particularly susceptible to the secondary rupture process. Such local clustering of diseased vessels has been previously suggested in patients with CAA, since macrobleeds and microbleeds tend to occur in proximity within any given patient [13].

Additional support for the secondary rupture model of hemorrhage expansion was recently provided by a correlative genotyping-neuroimaging study, which demonstrated that presence of the apolipoprotein E ε2 allele predisposes to lobar ICH expansion, particularly in patients with CAA [14]. Given that the apolipoprotein E ε2 allele is associated with amyloid-related vasculopathy [15], this finding suggests that the neuroanatomic distribution of fragile, amyloid-laden vessels may play a role in determining the temporal and spatial dynamics of secondary vessel rupturing during hemorrhage expansion. Moreover, another line of evidence indirectly supporting a secondary shearing model of hemorrhage expansion is the observation that hemorrhages in CAA patients occur in a bimodal distribution of volumes [16], suggesting a possible size threshold beyond which a growing hemorrhage will continue to expand from the microbleed peak fully into the macrobleed peak. Similar to serial neuroimaging results reported here, the results of these prior studies are difficult to explain on the basis of continuous bleeding from a single source vessel and argue against this possibility.

The neuroimaging findings in this case therefore add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the prevention of secondary vessel rupture may be a potential therapeutic target to reduce hemorrhage expansion. New methods for reducing hematoma expansion are being actively sought, since previously reported approaches such as hemostatic therapy [17] and blood pressure reduction [18, 19] have yet to demonstrate clinical benefit. Determination of the precise mechanisms underlying hematoma expansion is likely to be an important step towards devising new therapies for limiting this potentially devastating complication of ICH.

Supplementary Material

Hyperacute hemorrhage expansion. Hemorrhage expansion is shown at each sequential time point of MRI and CT data acquisition, with time displayed in hour:minute format and with the corresponding hemorrhage volume displayed at each time point. The first part of the video displays hemorrhage expansion from a superior view, with 3-dimensional renderings of the hemorrhage (red) superimposed on an axial T1-pre contrast image at the level of the cerebral microbleed seen on the gradient-recalled echo sequence. In the second part of the video, hemorrhage expansion is displayed from a posterior view, with 3-dimensional renderings of the hemorrhage superimposed on the same T1-pre contrast axial image, as well as a T1-pre contrast coronal image at the level of the thalamus. Of note, all images are displayed in non-radiological orientation, with the left side of the image (L) on the left side of the screen, and the right side of the image (R) on the right side of the screen.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the NIH (R25NS065743).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest or pertinent financial disclosures.

Electronic supplementary material: This manuscript contains one supplementary video file.

Contributor Information

Brian L. Edlow, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Riley M. Bove, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Anand Viswanathan, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Steven M. Greenberg, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Scott B. Silverman, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

References

- 1.Kazui S, Naritomi H, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Incidence and time course. Stroke. 1996;27:1783–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, et al. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii Y, Takeuchi S, Sasaki O, Minakawa T, Tanaka R. Multivariate analysis of predictors of hematoma enlargement in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1998;29:1160–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.6.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher CM. Pathological observations in hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1971;30:536–50. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong D, Jhaveri MD, Prabhakaran S. Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics at onset of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:826–7. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, Greenberg SM. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology. 2001;56:537–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kothari RU, Brott T, Broderick JP, et al. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke. 1996;27:1304–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(1):S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells WM, 3rd, Viola P, Atsumi H, Nakajima S, Kikinis R. Multi-modal volume registration by maximization of mutual information. Med Image Anal. 1996;1:35–51. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang R, Wedeen VJ. TrackVis, Version 5.2. Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging Massachusetts General Hospital; Charlestown, MA: 2011. http://www.trackvis.org. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher CM. Hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage. Demonstration of the source of bleeding. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:104–7. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg CH, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM. Modeling the Growth of Microbleeds into Macrobleeds (P485) Stroke: Abstracts from the 2010 International Stroke Conference. 2010;41:e376. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosand J, Muzikansky A, Kumar A, et al. Spatial clustering of hemorrhages in probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:459–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.20596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwers HB, Biffi A, Ayres AM, et al. Apolipoprotein e genotype predicts hematoma expansion in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:1490–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.643262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg SM, Vonsattel JP, Segal AZ, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E epsilon2 and vasculopathy in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 1998;50:961–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg SM, Nandigam RN, Delgado P, et al. Microbleeds versus macrobleeds: evidence for distinct entities. Stroke. 2009;40:2382–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.548974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2127–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson CS, Huang Y, Wang JG, et al. Intensive blood pressure reduction in acute cerebral haemorrhage trial (INTERACT): a randomised pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:391–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ATACH Investigators. Antihypertensive treatment of acute cerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:637–48. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9e1a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Hyperacute hemorrhage expansion. Hemorrhage expansion is shown at each sequential time point of MRI and CT data acquisition, with time displayed in hour:minute format and with the corresponding hemorrhage volume displayed at each time point. The first part of the video displays hemorrhage expansion from a superior view, with 3-dimensional renderings of the hemorrhage (red) superimposed on an axial T1-pre contrast image at the level of the cerebral microbleed seen on the gradient-recalled echo sequence. In the second part of the video, hemorrhage expansion is displayed from a posterior view, with 3-dimensional renderings of the hemorrhage superimposed on the same T1-pre contrast axial image, as well as a T1-pre contrast coronal image at the level of the thalamus. Of note, all images are displayed in non-radiological orientation, with the left side of the image (L) on the left side of the screen, and the right side of the image (R) on the right side of the screen.