Abstract

Introduction

Endometrial cancer patients with high grade tumours, deep myometrial invasion, or advanced stage disease have a poor prognosis. Randomized studies have demonstrated prevention of loco-regional relapses with radiotherapy with no effect on overall survival. The possible additive effect of chemotherapy remains unclear. Two randomized clinical trials (NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-55991 and MaNGO ILIADE-III) were undertaken to clarify if sequential combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy improves progression-free survival in high-risk endometrial cancer. The two studies were pooled.

Methods

Patients (n=540; 534 evaluable) with operated endometrial cancer FIGO stage I-III with no residual tumour and prognostic factors implying high-risk were randomly allocated to adjuvant radiotherapy with or without sequential chemotherapy.

Results

In the NSGO/EORTC study, combined modality treatment was associated with a 36 % reduction in the risk for relapse or death (HR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.41-0.99; P=0.04); two-sided tests were used. The result from the MaNGO-study pointed in the same direction (HR 0.61), but was not significant. In combined analysis, the estimate of risk for relapse or death was similar but with narrower confidence limits (HR 0.63, CI 0.44-0.89; P=0.009). Neither study showed significant differences in overall survival. In combined analysis, overall survival approached statistical significance (HR 0.69, CI 0.46-1.03; P = 0.07) and cancer-specific survival was significant (HR 0.55, CI 0.35-0.88; p=0.01).

Conclusion

Addition of adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation improves progression-free survival in operated endometrial cancer patients with no residual tumour and high risk profile. A remaining question for future studies is if addition of radiotherapy to chemotherapy improves the results.

Keywords: adjuvant therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, endometrial cancer, randomised clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynaecologic cancer in the Western world. It was estimated that worldwide around 200 000 women acquired and 50 000 died of endometrial cancer in 20021. The prognosis for early stage endometrial cancer is excellent, but subgroups with a high risk for micrometastatic disease have been identified2. Randomized studies demonstrate high locoregional control in early stage endometrial cancer with adjuvant pelvic external radiotherapy (RT)3-6. However, overall survival (OS) remains largely unaffected. It is therefore likely that patients at risk for micrometastatic disease will benefit from systemic adjuvant therapy.

The Nordic Society of Gynecologic Oncology/European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (NSOG/EORTC) trial was designed to investigate if the addition of systemic chemotherapy (CT) to pelvic RT would improve progression-free survival (PFS) and OS for patients with endometrial cancer at high risk for micrometastatic disease. After presentation of the preliminary results at American Society of Clinical Oncology 20077 it was decided to publish the study together with the results from a similar trial (ILIADE-III) performed by the Gynaecological Oncology group at the Mario Negri Institute (MaNGO). The results of the ILIADE-III was not known.

When these studies were planned Thigpen and colleagues had presented their randomised trial of doxorubicin+cisplatin versus doxorubicin at ASCO 19938. This regimen was chosen in both studies.

We report the results of the NSGO/EORTC and the MaNGO trials, and an analysis of pooled data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The NSGO-9501/EORTC 55991 trial

The inclusion criteria were histologically verified endometrial cancer, surgery with total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (lymphadenectomy (LA) was optional), no residual postoperative macroscopic tumour, FIGO 1988 surgical stage I, age ≤80 years, WHO performance status <3, and adequate bode marrow, liver, and kidney function. The risk assessment was based on FIGO stage, grade, and myometrial invasion. Most Swedish departments also used DNA ploidy. Patients were eligible if they had a risk profile that qualified for adjuvant treatment. Patients with serous, clear cell, or anaplastic carcinomas were eligible regardless of other risk factors. Exclusion criteria were: para-aortic lymph node involvement, squamous carcinoma or small cell carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation, pre-operative irradiation, and previous or concurrent malignant disease except for curatively treated carcinoma in situ of the cervix or basal cell carcinoma of the skin.

Amendment 1 August 2002 (237 patients included) allowed inclusion of patients with FIGO 1988 occult stage II, stage IIIA (only positive peritoneal fluid cytology), and stage IIIC (only positive pelvic lymph nodes without postoperative macroscopic residual tumour).

Randomization was performed centrally by the study office at Linkoping University Hospital for NSGO patients and at the EORTC Headquarters for EORTC patients. NSGO patients were randomized in blocks with stratification for centre and histology. The EORTC used a minimization procedure with the same stratification factors9.

Pelvic RT was given according to departmental guidelines (≥44 Gy). RT was given before CT in the RT-CT-arm. Optional vaginal brachytherapy had to be decided before randomization. Amendment 1 allowed the choice of sequence of RT and CT before randomization. CT consisted of four courses of doxorubicin/epirubicin 50 mg/m2 and cisplatin 50 mg/m2 every four weeks. Amendment 2 on Aug 2004 (291 patients included) allowed alternative CT regimens, including: Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2+epirubicin 60 mg/m2 or doxorubicin 40 mg/m2+carboplatin AUC 5 ; or paclitaxel 175 mg/m2+carboplatin AUC 5-6 every three weeks.

Patients were followed at three and six months after treatment and thereafter every six months for five years. A gynaecological examination was performed at each visit. A chest x-ray was to be taken annually.

The MaNGO ILIADE III-study

In 1996, the MaNGO group started the multicenter ILIADE-study in endometrial cancer, which consisted of three protocols. ILIADE-I investigated different techniques for hysterectomy10, ILIADE-II the question of LA11, and ILIADE-III adjuvant therapy.

The inclusion criteria for ILIADE-III were histologically confirmed endometrioid carcinoma, FIGO 1988 stage IIB, IIIA-C disease (stage IIIA with positive cytology alone without other risk factors was not included). Exclusion criteria: serous/clear cell carcinomas, performance status >2, previous malignancy except for basal cell carcinoma of the skin, surgical procedures less than total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (LA was optional), previous hormonal/chemo/radiotherapy for the present tumour, impaired cardiac function, evidence of any other serious disease, and inadequate bone marrow, liver, or kidney function.

Patients were randomized in blocks that balanced the treatment assignment within each site. Randomization was performed centrally by telephone at the Mario Negri Institute, Milan.

CT had to start within 30 days after surgery and consisted of doxorubicin 60 mg/m2+cisplatin 50 mg/m2 every three weeks for three cycles. The interval between CT and RT had to be less than four weeks, while patients allocated to RT alone had to start within 40 days after surgery. Pelvic RT was given with 1.8 Gy fractions; total dose 45 Gy. For patients with para-aortal metastases, a para-aortal field was added up to L1/L2. Vaginal brachytherapy was added for women with cervical stromal involvement.

Patients were monitored every three to four months during the first two years, every six months for the next three years, and then annually. Protocol recommended yearly computer tomography or ultrasound of the pelvis and abdomen for the first three years.

The study protocols were reviewed and approved by local ethics committees. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients and staff were not blinded to treatment assignment.

Statistics

The primary end-point was PFS. All times were counted from the time of randomization. PFS was defined as the time to progression of endometrial cancer or death from all causes. Secondary end-points were OS; the time to death of all causes, and cancer-specific survival (CSS); the time to death related to endometrial cancer.

Both studies aimed at detecting a 15 % absolute improvement in five year PFS from 60 % to 75 %. Assuming exponential survival distributions this corresponds to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.56. Because of different assumptions about inclusion and follow-up the number of patients in the NSGO/EORTC and the MaNGO-trials were predetermined to 400 and 300, respectively. The power calculation in the NSGO/EORTC-study was based on OS.

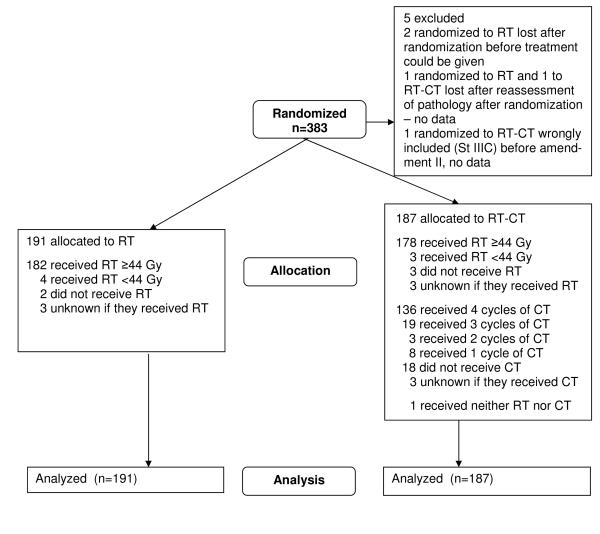

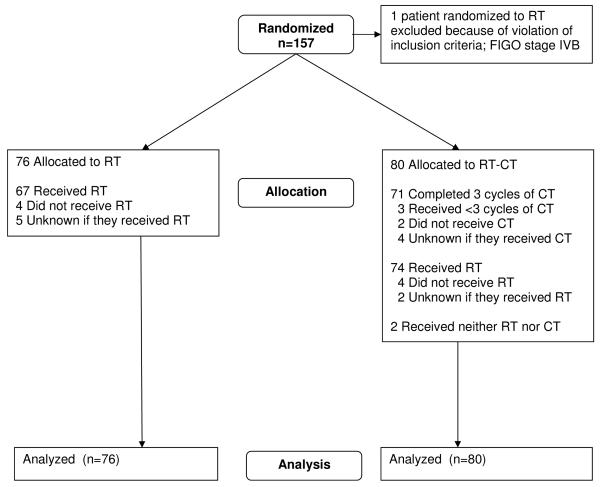

The NSGO/EORTC and MaNGO data-bases were locked August 19, 2009 and March 6, 2008, respectively. The intention-to-treat principle was used in the analyses after exclusion of five patients in the NSGO/EORTC-study (Figure 1a) and one patient with stage IV disease in the MaNGO-trial (Figure 1b). Survival curves were constructed by the Kaplan-Meyer technique. Survival differences between groups were expressed as hazard ratios and were analyzed with univariate Cox proportional hazard models12 with stratification for department. Departments which included less than four patients were aggregated within EORTC (n=6) and MaNGO (n=9), respectively; all sites in the NSGO randomized four or more patients). We also made a supportive Cox proportional hazard model with age, stage, grade, and cell type as covariates to check if the treatment effect was affected. To analyze potential heterogeneity of the treatment effect over subgroups, the interaction between treatment effect and group variable was evaluated and illustrated with forest plots13. Potential heterogeneity between study groups and after amendment 1 and 2 in the NSGO/EORTC-trial was analyzed with Cox-models and illustrated in a forest plot. Two sided tests were used for significance testing. We used Stata version 10 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Figure 1.

a: Consort Flowchart NSGO/EORTC-study. b: Consort Flowchart Iliade-study

RESULTS

Between May 1996 and January 2007, 383 patients were randomized in the NSGO/EORTC study, 320 from 13 NSGO departments and 63 from 12 EORTC departments (Figure 1a). In the MaNGO-study, 157 patients from 20 departments were randomized between October 1998 and July 2007 (Figure 1b). The treatment arms were well balanced regarding prognostic factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| NSGO/EORTC-study | MaNGO ILIADE III-study | Total n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT n (%) | RT-CT n (%) | RT n (%) | RT-CT n (%) | ||

| Randomization | 191 | 187 | 76 | 80 | 534 |

| Age | |||||

| Median (range) | 64 (44-79) | 64 (38-83) | 59 (42-78) | 58 (39-77) | 62(8-83) |

| FIGO stage | |||||

| IA | 27 (14) | 17 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 44 (8.2) |

| IB | 47 (25) | 62 (33) | 0 | 0 | 109 (20) |

| IC | 98 (51) | 92 (49) | 0 | 0 | 190 (36) |

| II | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.94) |

| IIA | 10 (5.2) | 7 (3.7) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 18 (3.4) |

| IIB | 0 | 2 (1.1) | 22 (29) | 29 (36) | 53 (10) |

| IIIA | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.53) | 19 (25) | 18 (23) | 40 (7.5) |

| IIIB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.19) |

| IIIC | 1 (0.52) | 1 (0.53) | 32 (42) | 31 (39) | 65 (12) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (3.9) | 0 | 9 (1.7) |

| Pelvic Lymphadenectomy | |||||

| No | 33 (17) | 37 (20) | 32 (42) | 44 (55) | 146 (27) |

| Yes | 28a (15) | 35b (19) | 41c (54) | 36d (45) | 140 (26) |

| Unknown | 130 (68) | 115 (61) | 3 (3.9) | 0 | 248 (46) |

| Vaginal brachytherapy | |||||

| No | 106 (56) | 96 (51) | 43 (57) | 46 (58) | 291 (54) |

| Yes | 75 (39) | 82 (44) | 21 (28) | 25 (31) | 203 (38) |

| Unknown | 10 (5.2) | 9 (4.8) | 12 (16) | 9 (11) | 40 (7.5) |

| Grade | |||||

| Grade 1 | 19 (10) | 15 (8.0) | 3 (4.0) | 7 (8.8) | 44 (8.2) |

| Grade 2 | 36 (19) | 31 (17) | 36 (47) | 46 (58) | 149 (28) |

| Grade 3 | 92 (48) | 108 (58) | 34 (45) | 27 (34) | 261 (49) |

| Not assigned or unknown e | 44 (23) | 33 (18) | 3 (3.9) | 0 | 80 (15) |

| Cell type | |||||

| Endometrioid | 112 (59) | 116 (62) | 72 (95) | 77 (96) | 377 (71) |

| Adenosquamous | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 7 (1.3) |

| Serous | 40 (21) | 34 (18) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 75 (14) |

| Clear cell | 36 (19) | 30 (16) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 67 (12) |

| Anaplastic | 0 | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (0.75) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (0.53) | 3 (3.9) | 0 | 4 (0.75) |

| Ploidy | |||||

| Non-diploid | 59 (31) | 63 (34) | 0 | 0 | 122 (23) |

| Diploid | 37 (19) | 38 (20) | 0 | 0 | 75 (14) |

| Polyploid | 3 (1.6) | 7 (3.7) | 0 | 0 | 10 (1.9) |

| Unknown | 92 (48) | 79 (42) | 76 (100) | 80 (100) | 327 (61) |

Eight of 28 patients also underwent para-aortal LA

Six of 35 patients also underwent para-aortal LA

Seven of 41 patients also underwent low para-aortal LA and 6 high para-aortal LA

Seven of 36 patients also underwent low para-aortal LA and 3 high para-aortal LA

Of the 80 with grade not assigned or unknown, 30 had serous, 36 clear cell carcinomas, and one had anaplastic carcinoma

Abbreviations: FIGO: International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy

Whether LA was performed was registered in EORTC patients and after Amendment 2 in the NSGO. Twenty-eight out of 61 patients in the RT-arm (46 %) had a pelvic LA; eight patients also underwent para-aortic LA. In the RT-CT- arm 35/72 (49 %) underwent pelvic LA; six also underwent para-aortic LA. In the MANGO-trial 41/76 (54 %) underwent systematic pelvic LA in the RT-arm; seven (9.2 %) also had low para-aortal and six (7.9 %) high para-aortal LA. While 36/80 (45 %) in the RT-CT-arm underwent systematic pelvic LA; seven (8.8 %) and three (3.8 %) had additional low or high para-aortic LA (Table 1).

The compliance to RT was high in the NSGO/EORTC-study, 182/191 (95 %) and 178/187 (95 %) received ≥44 Gy in the RT-arm and RT-CT-arm, respectively. Of the 187 patients assigned to CT, 136 (73 %) received four treatment cycles as planned. Eighteen (9.6 %) received no CT and the CT data was not available for three patients (1.6 %) (Figure 1a). Vaginal brachytherapy was used in 75/191 (39 %) of the cases in the RT-arm and 82/187 (44 %) in the RT-CT-arm (Table 1)

Most patients (138/166, 83 %) received doxorubicin/epirubicin+cisplatin, six patients (3.6 %) epirubicin+carboplatin, five (3 %) paclitaxel+epirubicin+carboplatin, and 17 (10 %) paclitaxel+carboplatin. Only 28 (17 %) had CT before RT and the sequence is unknown for seven (4 %).

Eight patients (5.1 %) in the MaNGO-trial did not undergo RT. Patients assigned to RT or RT-CT received the same median pelvic RT dose (50 Gy). Seventy-one out of 80 patients (89 %) completed three courses of CT, three (3.8 %) received less than three courses, two (2.5 %) did not start CT because of patients’ refusals, and CT data was missing for 4 patients (5.0 %) (Figure 1b). In the RT-arm 21/76 (28 %) received vaginal brachytherapy. The corresponding figure in the RT-CT-arm was 25/80 (31 %) (Table 1).

In the NSGO/EORTC-trial, there was one treatment related death three months after randomization in the RT-arm. No further details were available. There were 8 serious adverse events (SAE) in the RT-CT-arm: two cases with diarrhoea, one combined with neutropenia; three events with neutropenia one with pneumonia requiring respirator treatment; and another with associated nausea and vomiting; one patient with allergic reaction to paclitaxel; one case with an episode of atrial fibrillation; and one patient with bilateral pulmonary emboli 24 days after cycle one. There was one SAE in the RT-arm; an intestinal reaction with diarrhoea which led to cessation of RT after 36 Gy. All SAE’s resolved after appropriate treatment.

In the MaNGO-trial no treatment related death was registered. Analysis of toxicity was performed in 74 patients receiving at least one course of CT. The median cisplatin and doxorubicin doses per cycle were 50 (25th-75th percentiles = 49-50) and 60 (25th-75th percentiles = 56-60) mg/m2, respectively. The maximum grades of toxicities observed during treatment were: grade 3/4 leucopenia in 12 patients (16 %); grade 3/4 neutropenia in 22 (30 %); grade 2 thrombocytopenia in seven (9 %); grade 2 anaemia in seven (9 %); grade 3/4 nausea and vomiting in four (5 %); and grade 2/3 alopecia in 37 (50 %).

Disease progression was registered in 46/191 (24 %) and 28/197 (15 %) patients in the RT- and RT-CT-arm respectively in the NSGO/EORTC-study. The corresponding figures for the MANGO-trial were 24/76 (32 %) and 15/80 (19 %). Table 2 shows the progression sites.

Table 2.

Sites of progression

| RT (%) | RT-CT (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Loco-regional | 11 (16) | 5 (12) |

| Distant | 52 (74) | 35 (81) |

| Unknown/multiple sites | 7 (10) | 3 (7,0) |

| Total | 70 (100) | 43 (100) |

Abbreviations: RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy

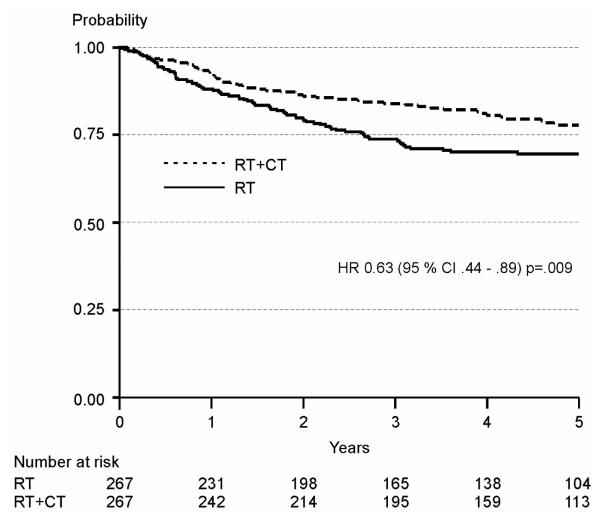

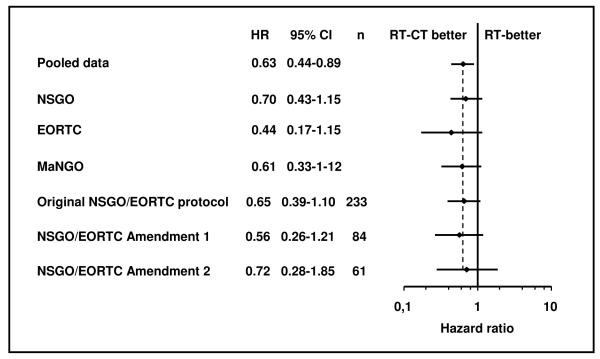

The difference in PFS between the treatment groups in the NSGO/EORTC-trial was significant, favouring RT-CT with, HR 0.64 (95 % CI 0.41-0.99) P=0.04 (Table 4). In the MaNGO-trial we found a non-significant difference of about the same magnitude (HR 0.61) (Table 3). When pooling the data from both studies there was a highly significant difference favouring RT-CT with HR 0.63 (95 % CI 0.41-0.99) P=0.009 (Figure 2, Table 2).

Table 3.

Results of survival analyses in different grous

| NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-55991 (RT n=191, RT-CT n=187) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-point | Events | HR | 95% CI | P | 5-yr probability of survival |

|||||

| RT | % | RT-CT | % | Total | RT | RT-CT | ||||

| PFS | 50 | 26 | 35 | 19 | 85 | 0.64 | 0.41-0.99 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| OS | 40 | 21 | 28 | 15 | 68 | 0.66 | 0.40-1.08 | 0.10 | 0.76 | 0.83 |

| CSS | 34 | 18 | 19 | 10 | 53 | 0.51 | 0.28-0.90 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.88 |

| MaNGO ILIADE III (RT n=76, RT-CT n=80) | ||||||||||

| PFS | 26 | 34 | 18 | 23 | 44 | 0.61 | 0.33-1.12 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.74 |

| OS | 17 | 22 | 14 | 18 | 31 | 0.74 | 0.36-1.52 | 0.41 | 0.73 | 0.78 |

| CSS | 15 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 26 | 0.65 | 0.30-1.44 | 0.29 | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| POOLED NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-55991+MaNGO ILIADE III (RT n=267, RT-CT n=267) | ||||||||||

| PFS | 76 | 28 | 53 | 20 | 129 | 0.63 | 0.44-0.89 | 0.009 | 0.69 | 0.78 |

| OS | 57 | 21 | 42 | 16 | 99 | 0.69 | 0.46-1.03 | 0.07 | 0.75 | 0.82 |

| CSS | 49 | 18 | 30 | 11 | 79 | 0.55 | 0.35-0.88 | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0.87 |

| NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-55991 endometrioid carcinoma (RT n=115, RT-CT n=120) | ||||||||||

| PFS | 29 | 25 | 19 | 16 | 48 | 0.50 | 0.27-0.95 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.83 |

| OS | 25 | 22 | 15 | 13 | 40 | 0.55 | 0.28-1.09 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.86 |

| CSS | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | 33 | 0.42 | 0.19-0.93 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-55991 serous and clear cell carcinoma (RT n=76, RT-CT n=64) | ||||||||||

| PFS | 21 | 28 | 16 | 25 | 37 | 0.83 | 0.42-1.64 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.72 |

| OS | 15 | 20 | 13 | 20 | 28 | 0.94 | 0.42-2.08 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| CSS | 12 | 16 | 8 | 13 | 20 | 0.71 | 0.26-1.90 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| POOLED NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-55991+MaNGO ILIADE III endometrioid carcinoma (RT n=187, RT-CT n=197) | ||||||||||

| PFS | 54 | 29 | 35 | 18 | 89 | 0.53 | 0.34-0.83 | 0.005 | 0.69 | 0.80 |

| OS | 41 | 22 | 27 | 14 | 68 | 0.60 | 0.36-1.00 | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.84 |

| CSS | 36 | 19 | 21 | 11 | 57 | 0.51 | 0.29-0.91 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval, CSS cancer-specific survival, HR: hazard ratio, OS: overall survival, PFS: progression-free survival, RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy .

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival in the pooled NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-5591 and MaNGO studies. (CI: Confidence interval, HR: Hazard ratio, RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy).

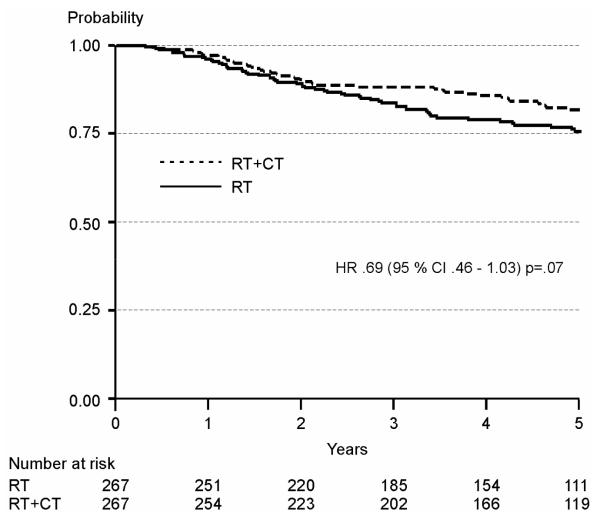

Neither the NSGO/EORTC nor the MaNGO-trial (Table 2) showed significant differences in OS. The analysis of the pooled data approached statistical significance with HR 0.69 (95 % CI 0.46-1.03) P =0.07) (Figure 3, Table 2). The OS curves are almost equal up to about two years and then they tend to split up in favour of RT-CT.

Figure3.

Overall survival in the pooled NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC-5591 and MaNGO studies. (CI: Confidence interval, HR: Hazard ratio, RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy)

The difference favouring RT-CT was significant for CSS in the NSGO/EORTC-trial with HR 0.51 (95 % CI 0.28-0.90) P =0.02, but not in the MaNGO-trial (HR 0.65). There was a significant difference in the pooled data favouring RT-CT with HR 0.55 (95 % CI 0.35-0.88) P=0.01 (Table 2).

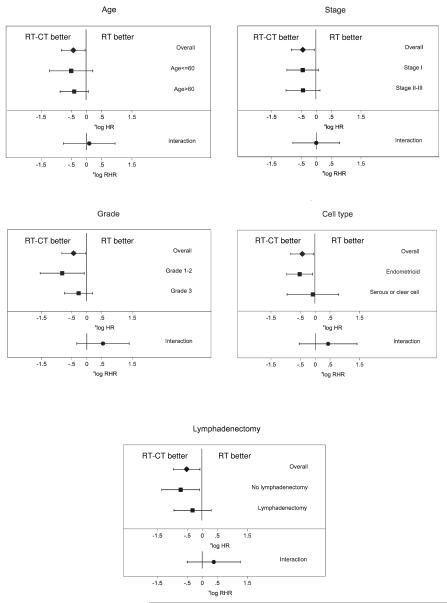

A Cox proportional hazard model on 447 patients with no missing values in any of the covariates (214 randomized to RT and 233 to RT-CT) with age, stage, grade, and cell type as covariates, stratification for department, and PFS as the endpoint demonstrated that the treatment effect was stable after adjustment for prognostic factors. The HR was 0.65 (95 % CI 0.43-0.99) compared with 0.63 (95 % CI 0.42-0.93) without adjustment for covariates. The analysis of heterogeneity of treatment effect on PFS in patient subgroups was performed on the same patients as the Cox model above, except that three further patients with anaplastic/undifferentiated tumours were excluded. LA could only be analysed in the subset where this was registered (n=286). There was no evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect in regards to age, grade, stage, cell type, or LA (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows another forest diagram exploring if there was heterogeneity between study groups and amendments in the NSGO/EORTC trial. As can be seen the treatment effect is similar.

Figure 4.

Forest plots for interaction between prognostic factors and treatment. The analysis was performed on 444 patients with no missing values for all covariates with progression-free survival (PFS) as the end-point. The analysis of lymphadenectomy was performed on 286 patients with information about lymphadenectomy. The upper bar in each diagram depicts the overall hazard ratio (HR), and the two middle bars show the HR by covariate group. The lowest bar shows the ratio of hazard ratios (RHR), which is a measure of interaction; if it crosses the vertical line there is no significant interaction, which is the case for all five covariates. (RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy).

Figure 5.

Forest plot with progression-free survival (PFS) as end-point illustrating possible heterogeneity depending on study group (NSGO, EORTC, or MaNGO), and original protocol, amendment 1, or 2 in the NSGO/EORTC-trial. (CI: Confidence interval, HR: Hazard ratio, RT: radiotherapy, RT-CT: sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy).

The apparent lack of effect in serous and clear cell carcinomas led to an unplanned data-driven subgroup analysis of endometrioid carcinomas in the pooled population (n=384). For PFS, the HR was 0.53 (95 % CI 0.34-0.83) P=0.005 which translates to 11 % absolute difference in 5-year survival from 69 % to 80 % favouring RT-CT. Even OS was of borderline significance, HR 0.60; P =0.05 (Table 2). For the 140 patients with serous or clear cell carcinoma in the NSGO/EORTC-study, the HR for PFS was 0.83 (95 % CI 0.42-1.64) P=0.59 (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The NSGO/EORTC-trial showed that the sequential addition of CT to RT was associated with a significant 36 % reduction in the risk of relapse or death and a significant 49 % reduction in the risk of death from endometrial cancer. The results in the MaNGO-trial point in the same direction but are not significant, likely because of the small study population. The NSGO/EORTC- and MaNGO-trials addressed the same question but in slightly different patient groups. The NSGO/EORTC-trial initially included only patients with FIGO stage I disease, but later also allowed inclusion of stage II and III. However, relatively few patients with higher stages were included. The MaNGO-trial included patients with more advanced stage disease (FIGO stage II-III). Serous/clear cell carcinomas were included in the NSGO/EORTC-trial while they were excluded in ILIADE. Otherwise, these two randomized studies were fairly similar and it seemed reasonable to pool the data to increase the statistical power and get a more representative stage distribution. With pooled data the estimates were similar but with narrower confidence limits. The 31 % risk reduction of death from any cause in the pooled data still only approached statistical significance. Endometrial cancer mainly affects elderly women and the risk of death due to intercurrent disease is fairly high. There was a significant 45 % risk reduction when looking at cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Endometrial cancer is a radiosensitive tumour. Adjuvant external RT prevents the majority of pelvic disease progressions, but many patients still die of distant metastatic disease 3-6,14. It has long been obvious that an effective systemic adjuvant therapy should be added to, or replace, adjuvant RT. The first randomized study (GOG-34) on adjuvant CT in endometrial cancer was initiated by the US Gynaecologic Oncology Group (GOG) already in 197715. After adjuvant pelvic external RT, patients were randomized to observation or to receive doxorubicin. The study was terminated prematurely because of slow recruitment and no significant difference in OS or PFS could be found between the treatment arms.

GOG-122 included 396 evaluable patients with FIGO stage III or IV endometrial carcinoma of any histology who after surgery were randomized to CT (8 cycles of a doublet regimen containing doxorubicin and cisplatin) or whole abdominal RT16. Both OS and PFS were significantly better for patients in the CT arm. However, this was not a pure study of adjuvant therapy since 16 % of the patients had residual postoperative tumours <2 cm.

In contrast, two other randomized studies, comparing RT against CT, failed to show superiority of adjuvant CT versus RT in terms of both disease-free survival and OS17,18. RT was compared with a three-drug regimen (cyclophosphamide+doxorubicin+cisplatin). Maggi and collegues17 suggested the two modalities may be complementary as RT seemed to achieve better locoregional control of the disease, while CT seemed to better control the distant spread. The main difference between these trials and our study is that we combined RT and CT in the experimental arm.

Limitations of our trials must be acknowledged. 1) The eligibility criteria allowed inclusion of patients with several risk levels of the disease. Although the five-year survival rates in the control arm were consistent with other similar trials4-6,17,18 the prognostic profile of many patients was rather favourable and this might have reduced the statistical power. 2) We used different CT regimens. However, all were well validated for the salvage treatment of endometrial cancer. The majority (90 %) received a combination of anthracycline and platinum. The aim of the studies was to find out if systemic therapy added to RT could improve survival, and not to evaluate the efficacy of any specific regimen. We thought it appropriate to allow different regimens to increase inclusion rate. 3) Quality of life data was only registered in some of the patients and has not been analysed. 4) Lympadenectomy was optional and was only registered and performed in a fraction of the patients.

A supportive Cox analysis of the pooled material from the NSGO/EORTC and MaNGO showed that the treatment effect on PFS remained unaffected with age, stage, grade, cell type, and LA no/yes as covariates, and we found no evidence that the PFS benefit for RT-CT compared with RT differed within subgroups (stage I/stage II-III, patients aged ≤60/older, grade 1-2/3, or LA performed or not). It is interesting to note that for serous/clear cell carcinomas, the treatment effect was negligible, although with wide confidence intervals. The same tendency could be seen in GOG-12216, where the HR for death in the 83 women with serous carcinomas was slightly above 1.0 in contrast to the HR of 0.48 favouring CT for the endometrioid cell types. Chemotherapy is often recommended for patients with serous/clear cell carcinomas. However, neither the present study nor GOG-122 support that recommendation. On the other hand, none of the studies can rule out an effect.

We have shown that RT-CT seems superior to RT alone. However, many important questions remain and need to be clarified by future studies. The ongoing International Postoperative Radiotherapy in Endometrial Cancer study (PORTEC-3) compares adjuvant pelvic RT with concomitant cisplatin followed by four courses of paclitaxel+carboplatin (modified from the The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trial19) with standard RT. Should the PORTEC-trial confirm the superiority of the combined modality strategy it will still be unsettled how much RT adds to CT. Before combining two toxic therapies a study comparing RT-CT versus CT alone should be done. The NSGO has made a proposal (After 4) in the International Gynaecologic Cancer Intergroup setting comparing 4 courses of paclitaxel+carboplatin followed by RT versus 6 courses of paclitaxel+carboplatin.

Clinical trial registration.

The NSGO/EORTC-study is registered in the European Clinical Trials Database with EudraCT number 2004-002429-37 and in ClinTrials.gov with ID NCT 00005583 and registration date 02/05/2000.

The MaNGO- trial is registered in the Italian National Monitoring Centre for Clinical Trials http://oss-sper-clin.agenziafarmaco.it/project.htm trial code “ILIADE”.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Nordic Cancer Union (grant number 06 0004 to NSGO), Fondazione Mattioli to MaNGO, and the National Cancer Institute at, Bethesda, Maryland, USA (grants number 5U10 CA11488-30 through 5U10 CA011488-39 to EORTC). The funding organizations had no influence on study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

We thank all of the women who participated in this trial and the research staff that helped to recruit patients and provide data. We also thank the Clinical Trial Unit, Department of Oncology, Linköping University Hospital; the Regional Tumor Registry of Southeastern Sweden; the EORTC Headquarters for data management in the NSGO/EORTC-study; and the data center at the Mario Negri Institute for data management in the MaNGO- trial.

Other trial collaborators, listed alphabetically by name, include: Antonio Casada-Herreaz, Department of Medical Oncology, University Hospital San Carlos, Madrid, Spain; Paul Chinet-Charrot, Department of Oncology, Centre Henri Bequerel, Rouen, France; Stefano Greggi, Istitituto Nazionale per lo Studio e Cure dei Tumori, Napoli, Italy; Jan Jobsen, Medish Spectrum Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands; Angel J. Lacave, Department of Medical Oncology, Hospital General de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain; Christian Marth, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital Innsbruck, Insbruck, Austria; Saverio Tateo, Fondazione Policlinico S. Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Italy; and Päivi Vuolo-Merilä, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital, Oulu, Finland,

This study was supported by the Nordic Cancer Union (grant number 06 0004 to NSGO), Fondazione Mattioli to MaNGO, and the National Cancer Institute at, Bethesda, Maryland, USA (grants number 5U10 CA11488-30 through 5U10 CA011488-39 to EORTC).

Abreviations

- ASCO

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- CT

Chemotherapy

- EORTC

European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer

- FIGO

International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- GCIG

Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup

- GOG

Gynecologic Oncology Group

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LA

Lymphadenectomy

- NSGO

Nordic Society of Gynecologic Oncology

- MaNGO

Gynecologic oncology group at the Mario Negri Institute

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PORTEC

Postoperative radiotherapy in endometrial cancer (Dutch study group)

- RT

Radiotherapy

- RT-CT

Sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy (or chemotherapy and radiotherapy)

- SAE

Serious adverse events

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT: None declared.

REFERENCES

- (1).Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Beller U, Benedet JL, et al. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S105–S143. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Aalders JG, Abeler VM, Kolstad P, Onsrud M. Postoperative external irradiation and prognostic parameters in stage I endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;56:419–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Creutzberg CL, van Putten WLJ, Koper PCM, Lybeert MLM, Jobsen JJ, Wárlám-Rodenhuis CC, et al. Surgery and postoperative radiotherapy versus surgery alone for patients with stage-1 endometrial carcinoma: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1404–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Keys HM, Roberts JA, Brunetto VL, Zaino RJ, Spirtos NM, Bloss JD, et al. A phase III trial of surgery with or without adjunctive external pelvic radiation therapy in intermediate risk endometrial adenocarcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Blake P, Swart AM, Orton J, Kitchener H, Whelan T, Lukka H, et al. Adjuvant external beam radiotherapy in the treatment of endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC and NCIC CTG EN.5 randomised trials): pooled trial results, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:137–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61767-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hogberg T, Rosenberg P, Kristensen G, de Oliveira CF, de Pont Christensen R, Sorbe B, et al. A randomized phase-III study on adjuvant treatment with radiation (RT) +/− chemotherapy (CT) in early stage high-risk endometrial cancer (NSGO-EC-9501/EORTC 55991) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S) Abstract 5503. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Thigpen T, Blessing J, Homesley H, Malfetano J, Disaia P, Yordan E. Phase III trial of doxorubicin +/− cisplatin in advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993;12 Abstract 830. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Signorelli M, Lissoni AA, Cormio G, Katsaros D, Pellegrino A, Selvaggi L, et al. Modified radical hysterectomy versus extrafascial hysterectomy in the treatment of stage I endometrial cancer: results from the ILIADE randomized study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3431–41. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Benedetti PP, Basile S, Maneschi F, Alberto LA, Signorelli M, Scambia G, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1707–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. JR Statist Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Barthel FM-S, Royston P. Graphical representation of interactions. Stata Journal. 2006;6:358–63. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Scholten AN, van Putten WL, Beerman H, Smit VT, Koper PC, Lybeert ML, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for Stage 1 endometrial carcinoma: long-term outcome of the randomized PORTEC trial with central pathology review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:834–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Homesley HD, Creasman WT, Hornback ND, Kurman R, et al. Doxorubicine as an adjuvant following surgery and radiation therapy in patients with high-risk endometrial carcinoma, stage I and occult stage II: A GYnecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:166–71. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90166-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Fowler J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:36–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Maggi R, Lissoni A, Spina F, Melpignano M, Zola P, Favalli G, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy vs radiotherapy in high-risk endometrial carcinoma: results of a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:266–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Susumu N, Sagae S, Udagawa Y, Niwa K, Kuramoto H, Satoh S, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pelvic radiotherapy versus cisplatin-based combined chemotherapy in patients with intermediate- and high-risk endometrial cancer: a Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Greven K, Winter K, Underhill K, Fontenesci J, Cooper J, Burke T. Final analysis of RTOG 9708: adjuvant postoperative irradiation combined with cisplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy following surgery for patients with high-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]