Abstract

The chemical and physical properties of objects provide them with specific surface patterns of color and texture. Endogenous and exogenous forces alter these colors and patterns over time. The ability to identify these changes can have great utility in judging the state and history of objects. To evaluate the role of color cues in this process, we used images of 26 materials undergoing real changes. Observers were asked to identify materials and types of changes for color and gray-scale images. The images were shown in three sets; one image of the surface, two images of the same surface before and after a natural change, and image sequences of the time-varying appearance. The presence of color cues improved performance in all conditions. Identification of materials improved if observers saw two states of the material, but the complete image sequence did not improve performance.

Keywords: color and pattern, color and texture, color perception, material perception, reflectance changes

Introduction

There has been a much needed shift recently, away from measuring ‘color constancy’ for flat uniformly colored stimuli such as Munsell chips, and towards the perception of material qualities of real surfaces (Adelson et al., 2004; Motoyoshi et al., 2007; Sharan et al., 2008). This shift has been driven by the realization that whereas shape is important in object recognition, material perception can be just as important in identifying objects (Zaidi and Bostic, 2008) and their qualities (Adelson, 2001), e.g. natural vs artificial fruits, or soft vs hard seats. The cues identified by the studies on material perception have been based on achromatic image statistics. The aim of this paper is to test directly whether color cues add to material perception of familiar and unfamiliar objects.

The systematic study of material appearance may also remove another vestige of ‘color constancy’ studies – the assumption that material reflectances are constant over time (Maloney, 1999). Chemical and physical properties of objects provide them with specific surface patterns of color and texture. Endogenous and exogenous forces alter these colors and patterns over time (Zaidi, 1998). For example, fruits change colors and textures as they ripen and then decay; skin gets tanned, paint bleached, and foliage darker, by prolonged exposure to sunlight; repeated exposure to water creates characteristic patterns on stone and wood; metals corrode on exposure to air; etc. The perception of these changes can have great utility in judging the state and history of objects.

Although the facilitating role of color memory in object and scene recognition has been documented (Gegenfurtner and Rieger, 2000; Hansen et al., 2006; Nestor and Tarr, 2008; Oliva and Schyns, 2000; Wichmann et al., 2002; Yip and Sinha, 2002), it remains to be tested whether this facilitation is through material recognition. We know from experience that wood never rusts, and an iron plate does not burn. In addition, the spatial patterns may vary for distinct materials undergoing similar physical processes. A wet fabric dries with a different spatial pattern than a piece of wet wood, and burning changes the texture of wood in a different manner than it does the texture of bread. Identification of these changes may be based on memories that associate colors and patterns or textures.

The computer graphics community has recognized the importance of measuring time-varying material appearances for realistic rendering of objects (Dorsey et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2007). A particularly good image-set has been acquired by Gu et al. (2006). In the current study we used a subset of these images to explore the role of color in identifying materials and material changes.

Methods

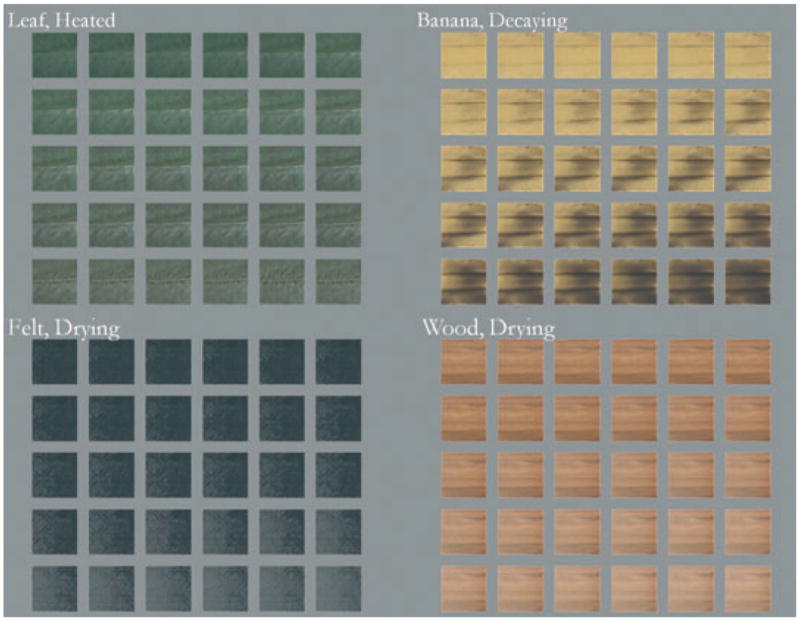

Three sets of material images were presented in color to five observers and in gray-scale to a different set of five observers. The images were taken from the STAF database (http://www1.cs.columbia.edu/CAVE/database/staf/staf.php). This database contains images of 26 types of materials undergoing various physical changes. A total of 724 images, consisting of 10–36 images of change in the 26 materials, were used in the experiment. The surfaces were always fronto-parallel to the camera sensor during image acquisition. All images were resized for display to 300 × 300 pixels using a bicubic interpolation algorithm. Lists of materials and the associated changes are shown in Table 1. Further information about the database and image acquisition can be found in Gu et al. (2006). The images were shown on a calibrated 20″ Mitsubishi Diamond Pro 2070SB CRT at a resolution of 1600 × 1200 from a distance of 1 m. Square images of the same size were used for 26 different materials to remove information about the shape of the object so that observers were limited to color and texture cues. The observers were informed that the images were acquired from real materials at a camera distance similar to the viewing distance. In the first condition, observers saw just one image of each material (Figure 1 left panel of each pair), and were asked to identify the material by typing the name. They were asked to type as specific a name as possible. In the gray-scale images, the color information was removed but the texture information was retained. In the second condition, observers saw two adjacent images of the same material across a physical change (Figure 1), e.g. a piece of wet fabric accompanied by the same piece completely dried. Observers were asked to describe the type of the material and the type of the change for colored and gray-scaled images. They were again asked to be as specific as possible in describing the perceived change. Finally, in the third condition, observers were presented with a set of images showing the material changing over time (Figure 2 shows four examples). The number of images in each sequence varied between 10 and 36. Again, different groups of observers described the material type and the nature of the change for sets of color and gray-scale images.

Figure 1.

Twenty six samples from the STAF database; first (left) and last image (right) in the change sequence.

Figure 2.

Examples of materials with the sequence of images showing their changes over time.

Observers’ responses were recorded as raw texts. The responses were carefully compared by the first author to the categories in Table 1 and rated as correct or incorrect. Synonyms as well as broader categories were accepted as correct; e.g. biscuit instead of waffle or fruit instead of apple. Similar criteria were used for the descriptions of material changes.

Table 1.

The 26 materials and their changes used in the experiment

| No. | Material | Change | No. of images | No. | Material | Change | No. of images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wood | Burning | 10 | 14 | Steel | Rusting | 22 |

| 2 | Rock | Drying | 11 | 15 | Leaf | Under humid heat | 30 |

| 3 | Wood | Drying | 23 | 16 | Pattern cloth | Drying | 31 |

| 4 | Orange cloth | Drying | 33 | 17 | Apple slice | Decaying | 35 |

| 5 | Light wood | Drying | 34 | 18 | Granite | Drying | 27 |

| 6 | White felt | Drying | 28 | 19 | Tree bark | Drying | 11 |

| 7 | Quilted paper | Drying | 32 | 20 | Potato | Decaying | 36 |

| 8 | Cardboard | Drying | 29 | 21 | Charred wood | Burning | 31 |

| 9 | Wet brick | Drying | 32 | 22 | Waffle | Toasting | 30 |

| 10 | Apple core | Decaying | 33 | 23 | Bread | Toasting | 30 |

| 11 | Wood | Drying | 14 | 24 | Cast iron | Rusting | 35 |

| 12 | Green cloth | Drying | 30 | 25 | Copper | Patina | 34 |

| 13 | Banana | Decaying | 33 | 26 | Cast iron | Rusting | 30 |

Results

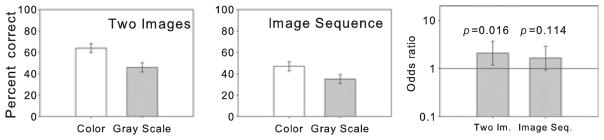

Percent correct performances for detecting the material type using single images, pairs, and sequences are shown in Figure 3, along with the odds-ratios comparing performance with and without color information. On average, the color information improved performances by a factor of two. Interestingly, adding a second image improved performance by more than 50%, but presenting the complete sequence of images did not improve observer’s performances. The odds-ratios for all the presentation types were significantly above 1.0, i.e. color information significantly increased the odds of identifying the materials.

Figure 3.

Average percent correct over five observers in each case for identifying the type of material in color and gray-scale images. The bottom row shows the log odds-ratio of the difference.

The performances of the observers for identification of the type of change using pairs or sequences of images are summarized in Figure 4. Again, color cues improved performance, but not as much as in the identification of material type. Surprisingly, the sequence of images did not improve observers’ performances.

Figure 4.

Average percent correct over five observers in each case for identifying the type of material change in color and gray-scale images. The extreme right figure shows the log odds-ratio of the difference.

While perusing observers’ qualitative responses, it seemed that there may be differences in identification accuracy across material categories. To test for this possibility, we reanalyzed the same data by assigning materials to the categories listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Material categories for data analysis

| Category | Materials |

|---|---|

| Organic | Apple, potato, leaf, waffle, banana, etc |

| Wood | All types of woods |

| Mineral | Rock, marble, granite, brick, etc |

| Metal | Copper, iron, etc |

| Fabric | Cloths, felts, paper, quilt, etc |

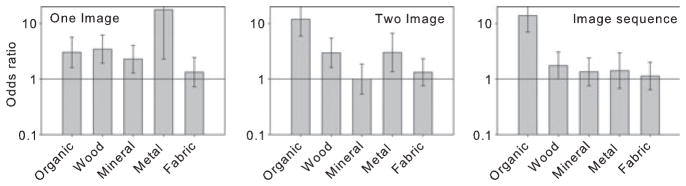

In these analyses, an answer was considered correct as long as it belonged to the correct category; e.g. if the banana was identified as a different organic material such as a potato, or a cloth was identified as paper. The results of these analyses are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Log odds-ratio for identifying the type of material category in color and gray-scale images.

In the categories constituting our sample of materials, wood and minerals were the easiest categories to identify correctly and metal was the most difficult. The unique grain of wood and the absence of a characteristic texture for metals might explain this difference. Color improved the identification rate in all conditions, but most dramatically in the organic category. This may be due to the fact that certain color patterns occur only in organic fruits and vegetables.

Conclusion

Using material appearance to estimate physical and chemical properties of objects would have great utility for organisms and may even be critical to survival in certain conditions. Recognizing color and texture changes that occur naturally can help observers make better judgments about types and properties of materials. Whether color information facilitates object and scene recognition is supported only by a few studies, but it is possible that color will take center stage as its role in material perception becomes clearer. The results of this study show that color is an important cue in this task and in some instances can improve performance dramatically.

Acknowledgments

Images are courtesy of Shree Nayar and Jinwei Gu, Columbia University. This work was supported by grants EY07556 & EY13312 to QZ.

References

- Adelson EH. On seeing stuff: the perception of materials by humans and machines. Proc Soc Photo Opt Instrum Eng. 2001;4299:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Adelson EH, Li Y, Sharan L. Image statistics for material perception. J Vis. 2004;4:123. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey J, Pedersen HK, Hanrahan P. Flow and changes in appearance. International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques; New York, NY: ACM; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner KR, Rieger J. Sensory and cognitive contributions of color to the recognition of natural scenes. Curr Biol. 2000;10:805–808. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00563-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Tu CI, Ramamoorthi R, Belhumeur P, Matusik W, Nayar S. Time-varying surface appearance: acquisition, modeling and rendering. International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques; New York, NY: ACM; 2006. pp. 762–771. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T, Olkkonen M, Walter S, Gegenfurtner KR. Memory modulates color appearance. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1367–1368. doi: 10.1038/nn1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Georghiades AS, Glaser A, Wu H, Wei LY, Guo BN, Dorsey J, Rushmeier H. Context-aware textures. ACM Trans Graph. 2007;26:Article 3. P3–es. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney LT. Physics-based approaches to modeling surface color perception. In: Gegenfurtner KR, Sharpe LT, editors. Color Vision: From Genes to Perception. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. pp. 387–422. [Google Scholar]

- Motoyoshi I, Shin’ya Nishida LS, Adelson EH. Image statistics and the perception of surface qualities. Nature. 2007;447:206–209. doi: 10.1038/nature05724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor A, Tarr MJ. Gender recognition of human faces using color. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:1242–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva A, Schyns PG. Diagnostic colors mediate scene recognition. Cogn Psychol. 2000;41:176. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharan L, Li Y, Motoyoshi I, Nishida S, Adelson EH. Image statistics for surface reflectance perception. J Opt Soc Am A. 2008;25:846–865. doi: 10.1364/josaa.25.000846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann FA, Sharpe LT, Gegenfurtner KR. The contributions of color to recognition memory for natural scenes. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2002;28:509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip AW, Sinha P. Contribution of color to face recognition. Perception-London. 2002;31:995–1004. doi: 10.1068/p3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi Q. Identification of illuminant and object colors: heuristic-based algorithms. J Opt Soc Am A. 1998;15:1767–1776. doi: 10.1364/josaa.15.001767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi Q, Bostic M. Color strategies for object identification. Vision Res. 2008;48:2673–2681. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]