Abstract

Social discounting assesses an individual's willingness to forgo an outcome for the self in lieu of a larger outcome for someone else. The purpose of the present research was to examine the effect of adding a common delay to outcomes in a binary choice, social discounting procedure. Based on the premise that both social and temporal distances are dimensions of psychological distance, we hypothesized that social discounting should decrease as a function of delay to the outcomes. Across two within-subject experiments, participants indicated preference between a hypothetical money reward for the self or for someone else. The outcomes were associated with no, short, and long delays. Both studies confirmed our hypothesis that adding any delay to the receipt of outcomes decreases social discounting, though no significant differences were observed between short and long delays. These results are discussed in the context of some existing literature on altruism.

1. Introduction

One conceptualization of intertemporal decision-making proposed by Parfit (1984) in Reasons and Persons (see review in Rachlin, 2010) is that the individual chooses between outcomes for the current self and outcomes for a different, future self (Rachlin, 2002; Read, 2001). The degree of overlap between these “selves” affects the degree to which an individual is self-controlled, i.e., prefers a large reward for the future self rather than a small reward for the current self. This conceptualization of self-control (intertemporal intrapersonal) behavior easily lends itself to comparisons with altruistic (intratemporal interpersonal) behavior. Just as greater overlap between the interests of the self and future selves produces self-control, greater overlap between the interests of the self and others may produce altruistic behavior (we use the term altruism here broadly, eschewing philosophical arguments on whether true altruism exists). On the basis of the philosophical commonalities, some researchers have hypothesized that self-controlled and altruistic behaviors are related (Ainslie, 2001; Rachlin, 2000; 2002; Read, 2001).

The connection between intrapersonal and interpersonal dilemmas has some empirical support (though any implications of this support is speculative and similarities across intertemporal and interpersonal behavior are not universal). Temporal discounting (the reduction of the subjective value of an outcome as a function of the delay to the outcome), assessed via intertemporal decision-making procedures, is positively correlated with cooperation in prisoner's dilemma games (Harris & Madden, 2002; Yi, Johnson, & Bickel, 2005), assessed via interpersonal decision-making procedures. Additionally, methodologically similar choice procedures to those employed in temporal discounting studies reveal that individuals discount outcomes for others (social discounting) as a function of increasing interpersonal distance and that hyperbolic models that describe temporal discounting also describe social discounting (Jones & Rachlin, 2006; Rachlin & Jones, 2008). Finally, brain regions associated with the ability to project oneself into the future are also associated with the ability to project oneself to others' perspectives (Buckner & Carroll, 2007).

These insights are consistent with Construal Level Theory (Trope & Liberman, 2003), which states that temporal and social distance are both dimensions of psychological distance and both have a similar influence on decision-making. Of interest in the present study is the finding that the addition of a common delay to an intertemporal choice decreases temporal discounting (i.e., increases self-control; Green, Myerson, & Macaux, 2005). For instance, an individual may prefer $50 now to $100 in 1 month but does not prefer $50 in 1 year to $100 in 1 year and 1 month (an added 1 year common delay), even though the 1-month separation between the pairs remains constant.

So if various dimensions of psychological distance share qualitative and quantitative characteristics, and if addition of a common delay to intertemporal choice results in greater self-controlled behavior, the addition of a common delay to interpersonal choice should result in greater altruistic behavior. Importantly, this derivation implicates the hyperbolic shape of the discount function as a cause of increased altruism (as it explains increased self-control in Green et al., 2005), in contrast to the literature that requires the influence of future moral priorities/concerns/values as the mediator of increased altruism (Agerstrom & Bjorklund, 2009; Eyal, Liberman, & Trope, 2008; Eyal, Sagristrano, et al., 2009; Wakslak, Nussbaum, et al., 2008).

The purpose of the present studies is to examine the influence of delay on interpersonal choice by employing a social discounting procedure in which individuals choose between rewards to self or to someone else (e.g., $75 for yourself or $100 for your best friend). We compare social discounting when rewards occur immediately versus when they are delayed, and expect that degree of social discounting will be lower (degree of altruism is higher) when outcomes are delayed than when outcomes are immediate.

2. Study 1

2.1 Method

Sixty-six college students completed three computerized social discounting tasks and received course points for participation. Participants were initially asked to think about 100 people they know and mentally rank them in order of closeness (closest = #1). In each computerized trial modeling the procedure of Rachlin and Jones (2008), participants were presented with two hypothetical alternatives: (A) a $100 outcome for one person that was mentally ranked and (B) a variable money outcome (between $0 and $100) for oneself. The persons of alternative A were individuals mentally ranked at the following levels of closeness: 1, 2, 3, 10, 25, 50, and 100. The amounts of alternative B were titrated across six trials (based on the algorithm of Holt, Green, & Myerson, 2003) to determine an indifference point for each person of alternative A (subjective equivalence between the amount for the other and the self). Though all outcomes were hypothetical, an extensive body of research indicates identity of intertemporal decision-making data for real and hypothetical money rewards (Johnson & Bickel, 2001; Madden, Begotka, et al., 2003), as well as identity of activated brain regions during those tasks (Bickel, Pitcock, et al., 2009).

The three social discounting tasks varied the delay to both the A and B outcomes: no delay, 6 months, and 12 months. The order of delay presentation was counterbalanced across participants. Area-under-the-curve (AUC) was selected as a model-free index of discounting and calculated according to Myerson, Green, and Warusawitharana (2001). High AUC values indicated less social discounting (greater altruism), and low AUC values more social discounting (less altruism).

2.2 Results

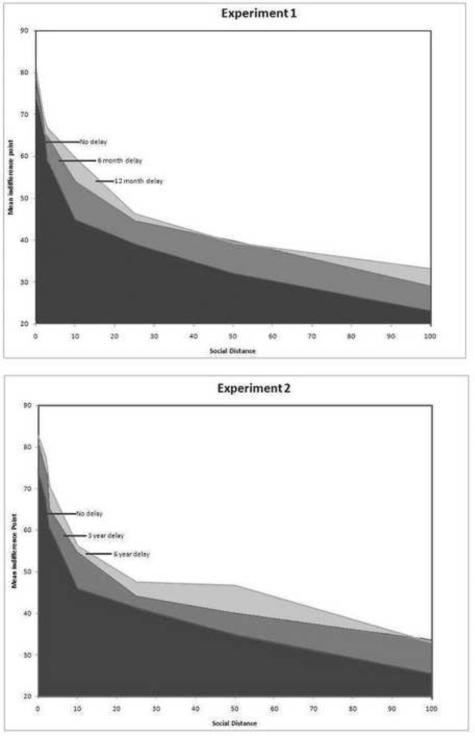

Pearson correlations revealed a strong, positive relationship between all social discounting conditions (Table 1). We divided participants according to their first delay condition to address possible order effects. This independent-measures factor was included in a mixed 3 (order) × 3 (delay) analysis of variance (ANOVA). A nonsignificant interaction (p = .81, η2 = .08) and main effect of order (p = .37, η2 = .03) revealed that order of exposure to the delay conditions did not differentially affect responses. In contrast, the primary hypothesis was supported with a significant main effect of delay (F(2,126) = 5.59, p < .005, η2 = .08; Fig. 1, top panel). Post-hoc Tukey's HSD comparisons among delays revealed a significant difference between no delay (M = 34.53) and a 6-month delay (M = 40.95; p = .04, η2 = .03) and between no delay and a 12-month delay (M = 43.06; p = .005, η2 = .05) in the predicted direction (greater discounting in the no-delay condition). Comparison between 6- and 12-month delays showed a nonsignificant difference (p = .73, η2 = .01) in the predicted direction (M = 40.95 and 43.06, respectively).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation matrix.

| Delay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| None | Short | Long | ||

| Study 1 | None | - | +.60* | +.64* |

| Short | - | - | +.78* | |

| Long | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||

| Study 2 | None | - | +.77* | +.63* |

| Short | - | - | +.69* | |

| Long | - | - | - | |

p < .0001.

Fig. 1.

Area-under-the-curve from mean indifference points in Study 1 (top panel) and Study 2 (bottom panel).

3. Study 2

Although we observed a decrease in social discounting in Experiment 1 in the presence of a delay, we did not see a significant difference between the 6- and 12-month delays. One possibility for this absence was that the temporal difference between the two delays was inadequate to detect differences. Therefore, we conducted a second experiment involving 3- and 6-year delays to determine whether social discounting is further reduced between short and long delays.

3.1 Method

Seventy-five college students completed three computerized social discounting tasks and received departmental course credit for participation. Procedures were identical to those of Study 1, with the exception of the use of the following delays: no delay, 3 years, and 6 years.

3.2 Results

Pearson correlations revealed a strong, positive relationship between all social discounting conditions (Table 1). A mixed 3 (order) × 3 (delay) ANOVA was conducted. As in Experiment 1, a nonsignificant interaction (p = .38, η2 = .01) and main effect of order (p = .18, η2 = .05) were observed. Additionally, a significant main effect of delay (F(2,144) = 6.41, p = .002, η2 =.08; Fig. 1, bottom panel) was observed, with significant differences between no delay (M = 36.85) and a 3-year delay (M = 42.53; p = .04, η2 = .03) and no delay and a 6-year delay (M = 46.04; p = .0005, η2 = .05) in the predicted direction. Comparison between 3- and 6-year delays showed a nonsignificant difference (p = .13, η2 = .02) in the predicted direction (M = 42.53 and 46.04, respectively).

Comparable conditions across studies (e.g., study 1 - short delay versus study 2 - short delay) were examined using between-groups t-tests, and no significant differences were observed (p > .05) in any comparison.

3. DISCUSSION

Interpersonal and temporal distances can be considered dimensions of psychological distance (Trope & Liberman, 2003) and individuals show greater self-control in temporal discounting with the addition of delays to both outcomes (Green, Myerson, & Macaux, 2005). Our hypothesis derives from a synthesis of these observations: that adding one dimension of psychological distance (temporal distance) to interpersonal choice (social distance) would result in greater altruistic behavior.

The results of these two experiments are consistent with our derived hypothesis: when the outcomes of the interpersonal choice procedure were delayed, participants were more likely to relinquish an outcome for the self in lieu of a better outcome for someone else in the same manner that behavior is more self-controlled in intertemporal choice when both outcomes are delayed. This study, within the framework proposed by Green, Myerson, and Macaux (2005), suggests a parsimonious behavioral explanation for changes in altruistic behavior as a function of the temporal distance to the outcomes. The addition of more psychological (temporal in this case) distance to self and other outcomes simply adds to the overall psychological distance of the outcomes. As a consequence of the hyperbola-shaped discount function (allowing for preference reversals), choice between outcomes with large and even-larger psychological distances increases the likelihood that the latter alternative will be preferred.

As noted previously, the social cognition literature suggests the current findings are a function of a mediating effect of the influence of moral concerns that increases as a function of delay (Agerstrom & Bjorklund, 2009; Eyal, et al., 2009; Wakslak, et al., 2008). With few exceptions, such studies query individuals on what they would do in the future or what would be a future moral priority. Though conceptually similar, this is very different from asking for a present decision with delayed outcomes, which commits an individual to the outcome. Thus the emphasis on moral concern may be due to the specific methodology of the literature. The current procedure avoids the necessity of relying on the mediating variable of moral concern as it commits an individual to one of the alternatives in the present regardless of whether the outcomes are immediate or delayed. In our procedure, the delay condition affects the timing of outcome delivery while keeping the choice rooted in the present.

The present studies are highly similar to human (Kirby & Herrnstein, 1995; Green, Fristoe, & Myerson, 1994) and nonhuman animal research (Rachlin & Green, 1972) that have demonstrated a preference for a smaller-sooner outcome (SS) over a larger-later outcome (LL) when the SS was immediate, but preference for the LL outcome when both outcomes occurred in the future. To the extent that self-control behavior is similar to altruistic behavior (Rachlin, 2000, 2002), this phenomenon was observed in the present study. Although commitment was imposed by the nature of the choice procedure, individuals made altruistic decisions in the present for outcomes in the future when the immediacy of the outcomes could not tempt choice away from the altruistic option as time passed.

Interestingly, while all results were in the predicted direction, no significant difference was observed between short and long delays in either experiment. This is somewhat surprising given that the long delays were twice as long as the short delays (6 to 12 months and 3 years to 6 years). A possible explanation for this is that adding any delay decreases social discounting and that extending that delay further does not have a substantial impact. Given that social discounting in both experiments decreased as a function of the increased delay, albeit by statistically nonsignificant margins, we believe that this explanation is unlikely. A more likely explanation is that the long delays were not adequately long enough to reveal significant differences between short and long delays. Because humans experience time nonlinearly (according to Weber-Fechner or Steven's power law), the effect of a unit delay on social discounting may diminish as overall delays get longer. For instance, one day added to a week may influence social discounting, whereas one day added to a year is unlikely to influence social discounting. Thus, for the long delay to be subjectively 2× the short delay, it would need to be objectively much longer. Though the delay conditions of studies 1 and 2 were not significantly different, this may be due to the diminished power of the necessary between-groups analysis.

The present results appear inconsistent with Kovarik (2009), who found that giving in the Dictator Game decreased as a function of delay to the outcomes. This discord will require future study, though it is likely due to methodological factors including differences in samples, magnitude to outcomes, and other procedural differences. For example, the Dictator Game determines giving to a single, unknown other where the amount that is given to the other is necessarily the amount that is lost to the individual (a one-to-one relationship of amount given and sacrificed). In contrast, the social discounting procedure of the current study incorporated a range of known others, particularly others whose welfare overlaps with the individuals' personal interest, and there is not a one-to-one relationship between giving and sacrifice. Alternatively, the present results may not be inconsistent with Kovarik (2009) if delay decreases the subjective value of outcomes (in the present delayed social discounting procedure and Kovarik's delayed Dictator Game), and the resulting low magnitude results in keeping more for the self in the Dictator Game.

One limitation of the observed results is that they were obtained with the use of only hypothetical outcomes. Though the literature overwhelmingly indicates no difference between real and hypothetical intertemporal choice, we are not aware of any published data comparing social discounting of real and hypothetical outcomes. A second limitation is that all participants in the reported experiments were college students. The two experiments reported here, nonetheless, provide strong evidence that altruistic behavior may be enhanced if the outcomes are delayed, and our results suggest that this delayed altruism effect is tied to the hyperbolic shape of the discounting function. Perhaps with the removal of the immediacy of reward for the non-altruistic act, individuals may be more likely to behave altruistically.

Acknowledgments

The data for this study were collected at the University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR. This research was partially funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA011692).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agerstrom J, Bjorklund F. Moral concerns are greater for temporally distant events and are moderate by value strength. Social Cognition. 2009;27:261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie G. Breakdown of will. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, U.K.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JP, Yi R, Angtuaco EJC. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: Fictive and real money gains and losses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:8839–8846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5319-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Carroll DC. Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal T, Liberman N, Trope Y. Judging near and distance virtue and vice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:1204–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal T, Sagristrano MD, Trope Y, Liberman N, Chaiken S. When values matter: Expressing values in behavioral intentions for the near vs. distant future. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Fristoe N, Myerson J. Temporal discounting and preference reversals in choice between delayed outcomes. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2005;1:383–389. doi: 10.3758/BF03213979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Macaux EW. Temporal discounting when the choice is between two delayed rewards. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2005;31:1121–1133. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.31.5.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AC, Madden GJ. Delay discounting and performance on the iterated prisoner's dilemma. Psychological Record. 2002;52:429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Holt DD, Green L, Myerson J. Is discounting impulsive? Evidence from temporal and probability discounting in gambling and non-gambling college students. Behavioural Processes. 2003;64:355–367. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BA, Rachlin H. Social discounting. Psychological Science. 2006;17:283–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Herrnstein RJ. Preference reversals due to myopic discounting of delayed reward. Psychological Science. 1995;6:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam KS, Gilbert DT, Boston A, Wilson TD. Future anhedonia and time discounting. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:1533–1537. [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik J. Giving it now or later: Altruism and discounting. Economic Letters. 2009;102:152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:139–145. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisan M, Koriat A. Children's actual choices and their conception of the wise choice in a delay-of-gratification situation. Child Development. 1977;48:488–494. [Google Scholar]

- Parfit D. Reasons and Persons. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. The Science of Self-control. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Altruism and selfishness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2002;25:239–296. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. How should we behave? A review of Reasons and Persons by Derek Parfit. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2010;94:95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Green L. Commitment, choice, and self-control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1972;17:15–22. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.17-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Jones BA. Social discounting and delay discounting. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2008;21:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Read D. Intrapersonal dilemmas. Human Relations. 2001;54:1093–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Temporal construal. Psychological Review. 2003;110:403–421. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakslak CJ, Nussbaum S, Liberman N. Representations of the self in the near and distant future. Attitudes and Social Cognition. 2008;95:757–773. doi: 10.1037/a0012939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Relationship between cooperation in an iterated prisoner's dilemma and the discounting of hypothetical outcomes. Learning and Behavior. 2005;33:324–336. doi: 10.3758/bf03192861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]