Abstract

Misregulated innate immune signaling and cell death form the basis of much human disease pathogenesis. Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein family members are frequently overexpressed in cancer and contribute to tumor cell survival, chemo-resistance, disease progression, and poor prognosis. Although best known for their ability to regulate caspases, IAPs also influence ubiquitin (Ub)-dependent pathways that modulate innate immune signaling via activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). Recent research into IAP biology has unearthed unexpected roles for this group of proteins. In addition, the advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that IAPs use to regulate cell death and innate immune responses have provided new insights into disease states and suggested novel intervention strategies. Here we review the functions assigned to those IAP proteins that act at the intersection of cell death regulation and inflammatory signaling.

IAPs inhibit caspases and cell death. They also control ubiquitin-dependent pathways that regulate activation of NF-κB and MAPK, which drive the expression of genes involved in inflammation and cell survival.

Apoptosis represents a fundamental biological process that relies on the activation of caspases. Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins represent a group of negative regulators of both caspases and cell death. Although best known for their ability to regulate caspases and cell death, it is now clear that they function as arbiters of diverse biological processes (Gyrd-Hansen and Meier 2010). Most prominently, IAPs control ubiquitin (Ub)-dependent signaling events that regulate activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways that in turn drive expression of genes important for inflammation, immunity, cell migration, and cell survival. IAPs thereby function as E3 Ub ligases, mediating the transfer of Ub from E2s to target substrates. This in turn modulates the signaling process through regulating protein stability as well as via nondegradative means (see below for details). Many of the cellular processes controlled by IAPs are frequently deregulated in cancer and, directly or indirectly, contribute to disease initiation, tumor maintenance, and/or progression, making IAPs obvious targets for anticancer therapy (LaCasse et al. 2008). Accordingly, small pharmacological inhibitors of IAPs, frequently referred to as Smac-mimetics (SM), were developed and are currently undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of cancer (LaCasse et al. 2008). The use of SMs in preclinical tumor models and clinical trials has provided compelling evidence for the therapeutic benefit of IAP inhibition.

ANATOMY OF IAP PROTEINS

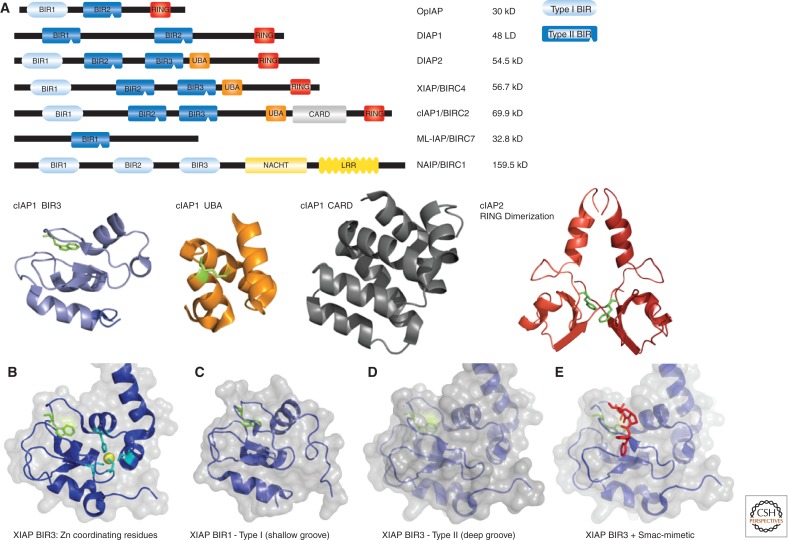

IAPs are defined by the presence of the baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domain(s) (Birnbaum et al. 1994), an approximately 70-residue-large zinc-binding domain that mediates protein–protein interactions. IAPs, of which there are eight in humans, carry one to three copies of this domain (Fig. 1). Drosophila IAP2 (DIAP2) and the mammalian IAPs, XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2, contain three such domains in their NH2-terminal portion. These IAPs also contain a Ub-associated domain (UBA) for binding to poly-Ub chains and a really interesting new gene (RING) domain that provides them with E3 ligase activity. In addition, cIAP1 and cIAP2 possess an evolutionary conserved caspase recruitment domain (CARD) that can inhibit their E3 ligase activity (Dueber et al. 2011; Lopez et al. 2011).

Figure 1.

Domain architecture of IAPs. The first IAP (OpIAP) was identified from a baculovirus strain in 1993 by Miller and colleagues, based on its ability to suppress virus-induced apoptosis of infected cells. Cellular IAPs were subsequently identified in insects and vertebrates. (A) Schematic and domain structures of some of the IAPs discussed in this review. All schematic IAPs, except NAIP, are drawn to scale, Leucine-rich repeats (LRR) and NACHT, the domain present in NAIP, CIITA, HET-E, and TP1. BIR domains provide interactions with proteins such as caspases, IAP-antagonists, TRAF1/2, and TAB1. cIAP1’s BIR3 is represented as a blue cartoon structure, and a highly conserved Trp in the IBM binding pocket is represented in green stick format. The UBA domain of cIAP1 binds to poly-Ub and is represented as an orange cartoon structure with a highly conserved Met represented in green stick format as a reference point. The caspase recruitment domain (CARD) present in cIAPs, which generally serves as a protein-interaction surface, has an unknown function in IAPs, and the CARD of cIAP1 is represented as a grey cartoon structure. The carboxy-terminal really interesting new gene (RING) domain is required for Ub-ligase activity and serves as dimerization interface and docking site for E2s. A dimeric cIAP2 structure is represented as a cartoon structure with each monomer in a different shade of red. A highly conserved Phe is represented in green stick format. Coordinates are from Dueber and colleagues (Dueber et al. 2011), PDB: 3T6P, and Mace and colleagues (Mace et al. 2008), PDB: 3EB5. (B) XIAP BIR3 with Zn ion (yellow sphere) and Zn coordinating cysteines and histidine are represented in cyan. Coordinates are from Mastrangelo and colleagues (Mastrangelo et al. 2008), PDB: 3CM2. (C) The BIR1 of XIAP (Type I) is represented as a cartoon and transparent surface, conserved Trp is indicated in green stick format. Coordinates are from Lu and colleagues (Lu et al. 2001), PDB: 2POI. (D) XIAP BIR3 (Type II). A conserved Trp residue in the IBM groove is represented in green stick format. (E) XIAP BIR3 bound to a Smac peptide is represented in red stick format. All crystal structure pictures were generated with PyMOL.

BIR Domain

The family-defining BIR domain functions as a protein-interaction surface through which IAPs bind to client proteins and adaptor molecules. BIRs possess a number of invariant amino acid residues, including three conserved cysteines and one histidine that coordinate a zinc ion, which is required to stabilize the BIR fold (Fig. 1B). Beyond these general features, individual BIRs can vary considerably, providing an explanation to why different BIR domains, even within the same protein, exhibit distinct functions (Eckelman et al. 2006; Srinivasula and Ashwell 2008). BIRs can be grouped into type-I and type-II domains based on the presence of a deep peptide-binding groove (Fig. 1C,D). Whereas type-I BIR domains lack a peptide-binding groove, or merely possess a shallow pocket (Fig. 1C), type-II BIRs carry a distinctive hydrophobic cleft through which they bind to IAP-binding motifs (IBMs) present in caspases and IAP-inhibitory molecules such as mammalian Smac/DIABlO (Fig. 1D,E) and Omi/HtrA2 or Drosophila Reaper, Grim, and Head Involution Defective (Hid), collectively referred to as IAP-antagonists. The main feature of an IBM is the presence of an NH2-terminal alanine. However, in some cases, IBMs can also harbor a serine at the first position (Verhagen et al. 2007). The NH2-terminal alanine or serine, which must be exposed and unblocked (devoid of NH2-terminal acetylation), inserts into the extensive hydrophobic cleft on the surface of type-II BIRs and forms hydrogen bonds with neighboring residues, thereby anchoring the IBM-carrying protein to IAPs (Wu et al. 2000). Subtle changes in the peptide-binding groove of type-II BIR domains alter their preference for particular client proteins with IBMs. Therefore, proteins with IBMs display differential and selective binding to specific type-II BIR domains. Apoptosis-regulatory IAPs such as XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2, and Drosophila IAP1 (DIAP1) and DIAP2 carry two such type-II BIR domains in tandem. The tandem arrangement (1) increases the repertoire of proteins with which they can interact, and (2) potentially enhances the binding-affinity to particular IBM-containing target proteins, particularly when they are dimeric or oligomeric in nature. In addition to type-II BIRs, apoptosis-regulatory IAPs, except DIAP1, also carry a type-I BIR domain. This BIR lacks an IBM-binding pocket and usually contains three additional residues, often including a proline, between the universally conserved glycine residue in the middle of the fold and the first zinc-binding cysteine residue. Consequently, type-I BIRs do not bind caspases or IAP-antagonists and use distinct modes to interact with a different set of target proteins. The BIR1 domain of XIAP, for example, directly binds to TAB1, an upstream adaptor of the transforming growth factor-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1). Analogously, the BIR1 of cIAP1 and cIAP2 associate with TRAF2, an adaptor that mediates signal transduction from members of the TNF receptor superfamily (Samuel et al. 2006; Varfolomeev et al. 2006; Vince et al. 2007). Thus, the type-I BIR domains link IAPs to specific signaling processes (see below for details). Mammalian Survivin, Drosophila DETERIN, Caenorhabditis elegans BIR1 and BIR2, Schizosaccharomyces pombe BIR1, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae BIR1p are IAPs that exclusively carry type-I BIR domains. As these IAPs do not possess a type-II BIR domain, they are unable to bind to caspases and IAP-antagonists. Instead, they are required for chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (Uren et al. 1999, 2000). Another IAP, BRUCE/Apollon, also appears to have a major role in cytokinesis, in particular in the abscission stage where the two daughter cells separate (Pohl and Jentsch 2008). BRUCE/Apollon is a membrane-associated IAP that carries only one BIR domain. Additionally, it also contains a Ub-conjugating (UBC) motif that can function as a Ub-E2, transferring Ub to substrates. In addition to contributing to cytokinesis, BRUCE/Apollon also safeguards cell viability by targeting caspase-9 and the IAP-antagonist protein Smac/Diablo for Ub-mediated proteasomal degradation (Bartke et al. 2004; Hao et al. 2004). In Drosophila, the activity of dBRUCE is indispensable for controlled activation of caspases required for spermatide individualization (Arama et al. 2003). Furthermore, dBRUCE also targets the IAP-antogonists Reaper and Grim for proteasomal degradation, thereby contributing to the apoptotic threshold (Vernooy et al. 2002; Domingues and Ryoo 2012).

RING Finger

In addition to a type-II BIR domain, apoptosis-regulatory IAPs also carry a carboxy-terminal RING finger domain that provides them with E3 ligase activity promoting the transfer of Ub to target proteins. Ub is a small protein modifier that is covalently attached to proteins in a stepwise process that involves Ub activating enzymes (E1), Ub-conjugating enzymes (E2), and Ub protein ligases (E3). E3s confer substrate specificity by bringing Ub-loaded E2 to target substrates and promoting the formation of an isopeptide linkage between the carboxyl terminus of Ub (glycine [G]76) and the amino group of a lysine (K) residue of the substrate. Ub can be conjugated either as a single moiety or as chains of variable length (Komander 2009). Further complexity is provided by different linkage types, as Ub moieties can be conjugated to one another via different K residues within Ub. In addition to K-mediated polyubiquitylation, Ub can also be attached to the NH2-terminus of Ub, creating M1-linked Ub chains in which Ub is conjugated to the initiating methionine of another Ub moiety (Kirisako et al. 2006). At least eight different types of Ub chains exist that exert distinct effects on cellular processes (Bhoj and Chen 2009). This is because the differently linked poly-Ub chains adopt distinct structures. For instance, K48-linked poly-Ub chains take up a kinked topology, whereas K63- and M1-linked chains resemble “beads-on-a-string” (Komander 2009). Although it is well established that K48-linked modifications can promote degradation through recognition by the 26S proteasome, recent evidence indicates that other linkage types, such as M1 and K63, can regulate biological processes in a degradation-independent manner (Komander and Rape 2012).

Whether ubiquitylation targets proteins for degradation or mediates nondegradative signaling depends on protein interactions between the ubiquitylated protein and Ub-binding proteins, which can therefore be considered as Ub “receptors” (Hoeller et al. 2006). Ub receptors carry specialized Ub-binding domains (UBDs) that enable them to interact with the specific linkage types and assemble Ub-dependent signaling hubs. The generation of K63- and M1-linked Ub chains are particularly important for the generation of Ub-dependent complexes that activate NF-κB and MAPK in response to cytokine signaling (Chen 2012; Schmukle and Walczak 2012). Studies in both mammalian systems and Drosophila have revealed that IAPs control apoptotic and innate immune signaling pathways via degradative and nondegradative ubiquitylation. Accordingly, IAPs have been found to mediate K48-, K63-, as well as K11-linked Ub chains.

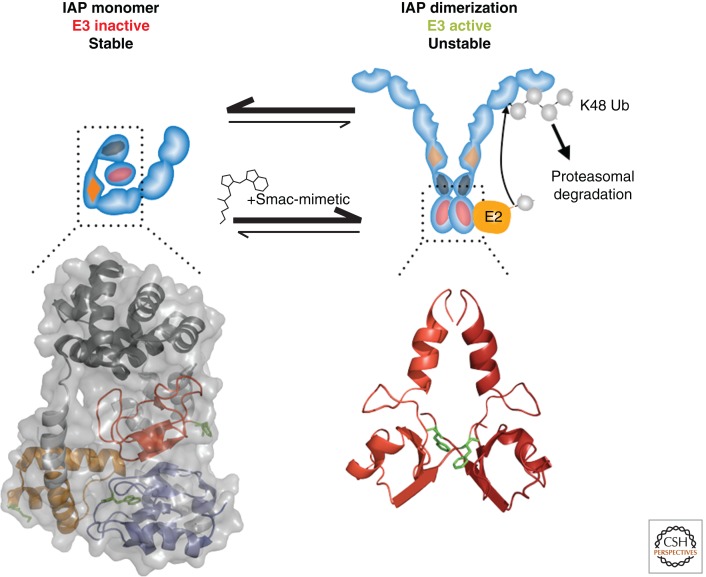

Regulation of E3 Activity

In the absence of signaling, cIAP1 resides in an inactive monomeric configuration (Fig. 2). This is achieved via an intramolecular interaction between cIAP1’s BIR3 and RING finger domain (Dueber et al. 2011; Feltham et al. 2011; Lopez et al. 2011), which prevents RING-dimerization, E2 binding, and E2 activation. Autoinhibition of cIAP’s E3 activity is supported by electrostatic intramolecular interactions via positively charged residues of the CARD (Dueber et al. 2011; Lopez et al. 2011). cIAP1’s E3 ligase activity can be activated following binding to a substrate. Substrate-binding to the BIR3 liberates the RING from BIR3-mediated inhibition, exposing two interaction surfaces required for RING dimerization and E2 binding, respectively (Mace et al. 2008). RING dimerization is of particular importance as it is indispensable for the transfer of Ub from the E2 to a lysine residue of the target substrate. Binding of SM to the BIR3 causes autoubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of cIAPs (Fig. 2). In effect, SMs mimic the presence of a substrate, leading to activation of cIAP’s E3 activity. However, in the absence of a bona fide protein substrate, lysine residues of cIAP1 serve as acceptor lysines for Ub, resulting in polyubiquitylation and degradation of cIAP1. Regulation of the E3 activity clearly differs among IAPs. cIAP2, which shares high sequence conservation with cIAP1, readily exists in a dimeric state (Feltham et al. 2011). Although this explains how SMs activate cIAP1’s auto-E3 ligase activity, it is currently unknown how the E3 activity of cIAP1, cIAP2, or XIAP are regulated in normal signaling processes.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of Smac-mimetic (SM)-induced activation of cIAPs. Monomeric cIAP1 BIR3, UBA, CARD RING, represented as in Fig. 1 using coordinates from Dueber and colleagues (Dueber et al. 2011), PDB: 3T6P, is an inactive E3 ligase. Binding of an SM releases the BIR3-mediated inhibition on RING dimerization (PDB:3EB5), resulting in activation of the E3 ligase function, auto-K48 ubiquitylation, and proteasomal degradation.

FUNCTION OF IAP PROTEINS

IAP-Mediated Regulation of Caspases and Cell Death

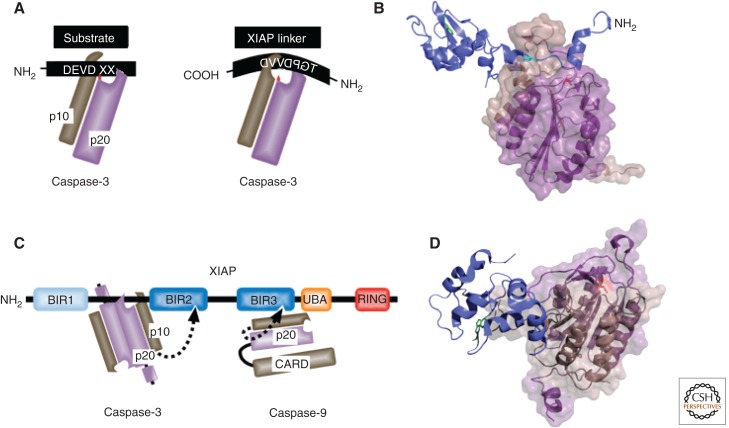

The apoptotic cell death program culminates in the activation of caspases, a family of highly specific cysteine proteases essential for the destruction of the cell. Caspases are expressed as zymogens consisting of a prodomain, a large subunit (p20), and a small subunit (p10) (Riedl and Shi 2004) (see also Fig. 4). Caspases reside in proteolytic cascades that are typically started by so-called initiator caspases, such as caspase-9 and caspase-8, which cleave and activate downstream effector caspases, such as caspase-3 and caspase-7 (Berger et al. 2006; Denault et al. 2006). Following zymogen activation, caspases are regulated by certain members of the IAP protein family (Salvesen and Duckett 2002). In Drosophila, DIAP1-mediated inhibition of caspases is essential for cell survival as loss of DIAP1 function instigates spontaneous caspase-mediated apoptosis (Rodriguez et al. 1999; Wang et al. 1999; Goyal et al. 2000; Lisi et al. 2000).

Figure 4.

XIAP-mediated inhibition of caspase-3 and caspase-9. (A) Schematic comparison of substrate and XIAP linker interaction with caspase-3, catalytic cysteine, indicated in red. (B) The BIR2 of XIAP and NH2-terminal linker (blue cartoon) embedded in the active site groove of the caspase-3 p10 (brown)/p20 (violet) heterodimer (PDB: 1I30), revealing the reverse (C-N) linker, cleavage incompatible, orientation. The reference Trp in the IBM binding groove of XIAP’s BIR2 is indicated in green, Asp148 in cyan, and the position of the catalytically active cysteine in the p20 of caspase-3 in red stick format. (C) The distinct mechanisms of caspase inhibition used by XIAP represented schematically. The BIR3 binds to a dimerization surface of a caspase-9 monomer, preventing it from dimerizing and autoactivating. (D) The structure (PDB: 1NW9) of the BIR3 of XIAP (blue) bound to caspase-9 (p10 in brown, p20 in violet). The conserved reference Trp in the IBM binding groove of BIR3 is indicated in green stick format and the position of the catalytic cysteine in red stick format.

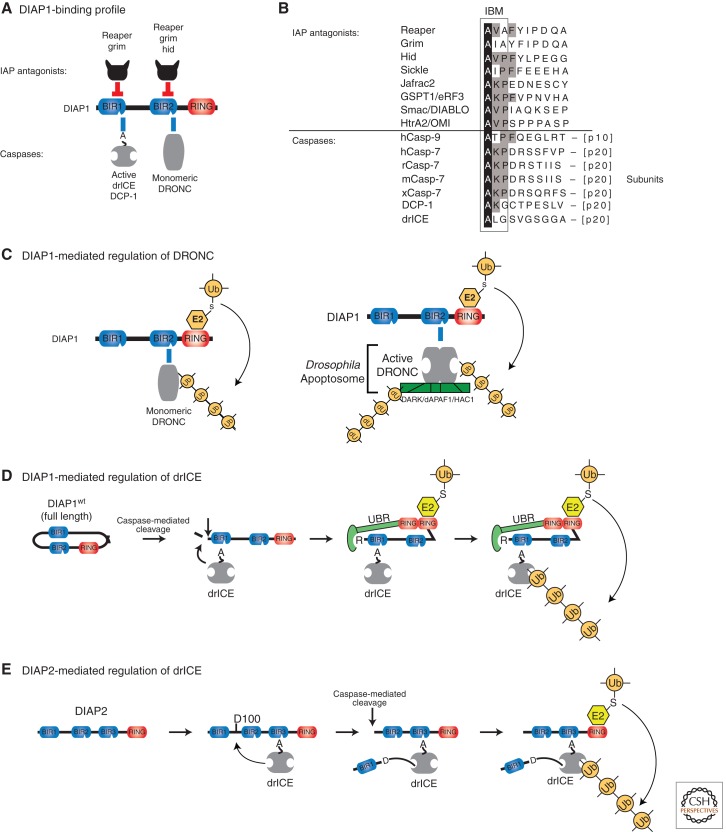

DIAP1 represents an essential negative regulator of the initiator caspase DRONC and the effector caspases drICE and DCP-1 (Fig. 3). These caspases bind to distinct BIR domains: the BIR1 region of DIAP1 is essential for binding to the effector caspases drICE and DCP-1 (Kaiser et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1999; Zachariou et al. 2003), whereas the BIR2 region directly associates with DRONC (Meier et al. 2000; Chai et al. 2003). Although DIAP1-caspase association is the decisive step in the regulation of Drosophila apoptosis, physical interaction between DIAP1 and caspases alone is insufficient to regulate caspases. This is evident because DIAP1-bound effector caspases remain catalytically active under in vitro conditions (Tenev et al. 2005). Moreover, DIAP1 mutants with a dysfunctional RING finger fail to suppress caspase-mediated cell death, even though these mutants bind to caspases with the same affinity as their wild-type counterparts. Therefore, DIAP1 does not act as a classical active-site enzyme inhibitor, but rather regulates the catalytic potential of caspases. Ultimately, suppression of caspases and apoptosis results from DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of the zymogenic form of DRONC (Fig. 3C) and active drICE or DCP-1 (Fig. 3D,E) (Lisi et al. 2000; Wilson et al. 2002; Chai et al. 2003; Ditzel et al. 2008). The mechanism through which ubiquitylation of DRONC results in its inactivation appears to be context dependent and involves degradative as well as nondegradative ubiquitylation (Fig. 3C). Outside of the apoptosome, DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of DRONC neutralizes it through an unknown mechanism that operates independent of the proteasome. However, when it is part of the apoptosome, DIAP1 conjugates K48-linked poly-Ub chains to DRONC, targeting it for proteasomal destruction (Shapiro et al. 2008). Hence, only apoptosome-associated DRONC (as well as DARK itself), but not free DRONC monomer, is targeted for proteasomal degradation. Interestingly, DRONC-mediated cleavage of DARK is required for proteasomal degradation of the DRONC/DARK complex, suggesting that the cleavage event recruits the E3 ligase (Shapiro et al. 2008).

Figure 3.

IAP-mediated regulation of caspases in Drosophila. (A) Binding profile of DIAP1 with caspases and IAP antagonists. Direct physical interaction with the effector caspases drICE or DCP-1 and the initiator caspase DRONC is mediated through DIAP1’s BIR1 and BIR2 domains, respectively. Following their activation, drICE and DCP-1 expose an NH2-terminal IBM (depicted as A), which allows their binding to BIR1. (B) Sequence alignment of IBM-bearing proteins. Identical residues are highlighted in black. Residues conserved in four or more IBM proteins are indicated in gray. (C) DIAP1’s BIR2-DRONC association is essential for DIAP1 to neutralize DRONC. Following binding, DIAP’s RING finger promotes Ub conjugation of DRONC, leading to its inactivation through nondegradative ubiquitylation of monomeric DRONC (left panel) and by targeting apoptosome-associated active DRONC for degradation (right panel). (D,E) Mechanism of effector caspase (drICE) inactivation by DIAP1 (D) and DIAP2 (E). (D) Full-length wild-type DIAP1 is held in an inactive conformation and requires caspase-mediated proteolytic cleavage at residue 20 for its activation. After cleavage, BIR-mediated caspase binding occurs more efficiently. Cleavage also facilitates recruitment of N-end rule UBR E3 ligases, which together with DIAP1’s RING domain, promote ubiquitylation and inactivation of drICE and DCP-1. (E) drICE is also subject to regulation by DIAP2. drICE binds to the BIR3 of DIAP2 in an IBM-dependent manner and, following binding, cleaves DIAP2 at D100. DIAP2 cleavage results in a covalent adduct between D100 and the catalytic machinery of drICE, trapping the caspase. Full inactivation of drICE is achieved through RING-mediated ubiquitylation.

DIAP1-mediated regulation of effector caspases is also dependent on the conjugation of Ub (Fig. 3D,E). Attachment of nondegradative (K63-linked) poly-Ub chains to the effector caspase drICE (homolog of caspase-3/-7) directly reduces its proteolytic potency, affecting kinetic parameters of the enzyme (Ditzel et al. 2008). Computational modeling of a ubiquitylated effector caspase suggests that the Ub chains sterically occlude the catalytic pocket of the caspase, thereby interfering with substrate entry. In addition to Ub, DIAP1 can also inactivate effector caspases via the covalent attachment of NEDD8. NEDD8-mediated suppression of drICE occurs via a mechanism that relies on noncompetitive inhibition, most likely through a NEDD8-induced conformational change of the caspase. Disruption of drICE ubiquitylation or NEDDylation, either by loss of DIAP1’s E3 activity or generation of a nonmodifyable form of drICE, renders this effector caspase resistant to DIAP1-mediated inactivation (Ditzel et al. 2008; Broemer et al. 2010). In addition to its own RING finger domain, DIAP1 recruits a second Ub-E3 ligase that belongs to the N-end-rule pathway (UBR), to effectively block caspase activity (Ditzel et al. 2003; Herman-Bachinsky et al. 2007; Tenev et al. 2007). Recruitment of the N-end rule E3 ligase requires caspase-mediated cleavage of DIAP1 and exposure of a docking site for the UBR at the neo-NH2 terminus of cleaved DIAP1 (Ditzel and Meier 2005). drICE, but not DRONC or DCP-1, is also regulated by the second Drosophila IAP, DIAP2.

DIAP2, based on its domain architecture, is the closest homolog of mammalian IAPs and directly regulates drICE and contributes to the overall caspase activity threshold in living cells. Consistently, diap2 mutant animals harbor increased levels of drICE activity and are sensitized to apoptosis following exposure to genotoxic stress (Zimmermann et al. 2002; Ribeiro et al. 2007). Conversely, overexpression of DIAP2 suppresses developmental cell death and phenotypes caused by apoptosis inducers (Hay et al. 1995). Moreover, it rescues apoptosis triggered by RNAi-mediated depletion of DIAP1 (Leulier et al. 2006b). However, compared to DIAP1, DIAP2 exhibits a more restricted specificity for caspases as it exclusively regulates drICE and does not bind other caspases (Leulier et al. 2006b).

Intriguingly, DIAP2 functions as a mechanism-based regulator of drICE, whereby it acts as a pseudosubstrate that, following cleavage, traps the active caspase via a covalent linkage between DIAP2 and the catalytic machinery of drICE (Ribeiro et al. 2007) (Fig. 3E). The mechanism of caspase inhibition of DIAP2 is highly similar to the one used by the viral caspase inhibitor p35, which also functions as a suicide substrate that locks on to the active caspase through a covalent linkeage with the catalytic cysteine of the caspase. DIAP2 mutants that cannot be cleaved fail to bind drICE and suppress drICE-mediated cell death. This method of enzyme inhibition is referred to as “mechanism based” because it relies on the activity of the enzyme. It is unusual for proteins that regulate enzymes to use a mechanism-based strategy, and most enzyme inhibitors, such as XIAP, avoid the catalytic machinery by simply blocking the substrate cleft. In addition to its mechanism-based interaction, DIAP2’s E3 ligase activity is also essential for proper drICE regulation (Ribeiro et al. 2007).

The mode of caspase regulation by DIAP1 and DIAP2 differs from that of mammalian XIAP, which is a potent, classical, active site enzyme inhibitor of caspases 3 and 7 (Fig. 4A,B) (Deveraux et al. 1997). Residues within a small segment that is NH2 terminal to XIAP’s BIR2 domain directly bind to a surface found above the active-site pocket of caspase-3 and caspase-7 that is specific for these caspases, explaining the selectivity of BIR2. This prevents substrate entry and thereby results in inhibition of the caspases’ catalytic activity. In this respect, XIAP acts as an inhibitor of caspases in a strict biochemical sense, blocking caspases through a “key-lock” type of mechanism (Eckelman et al. 2006). Surprisingly, the BIR2 domain itself plays little direct role in the inhibitory mechanism as almost all inhibitory contacts are made by the linker region preceding the BIR2 domain. Nevertheless, the BIR domain is functionally important as it makes additional contacts with residues outside of the catalytic pocket, thereby strengthening caspase binding. The strategy through which XIAP inhibits caspase-9 is fundamentally different (Fig. 4C,D). Here the BIR3 domain of XIAP binds to the homo-dimerization surface of caspase-9. This results in caspase-9 inactivation because caspase-9 requires a dimerization-induced conformational change to generate a productive catalytic pocket, which is no longer possible because XIAP interferes with caspase-9 dimerization. Other mammalian IAPs, such as cIAP1 and cIAP2, can also bind to caspases, particularly caspase-7, but are inefficient in inhibiting them through mere physical interactions under in vitro conditions.

Despite a large body of evidence showing that IAPs, and particularly XIAP, are important physiological regulators of caspases, Xiap−/−, Clap1−/−, and Clap2−/− knockout animals are surprisingly normal and display only limited cell-death related phenotypes. This seems to be due to a measure of functional redundancy among IAPs in mammals. Surprisingly, even Xiap−/−Clap2−/− animals are phenotypically normal (Moulin et al. 2012). However, Xiap−/−Clap1−/− and Clap1−/−Clap2−/− are embryonic lethal. Such embryos die at around embryonic day E10.5, which is at a similar time to when Caspase-8−/− mice die. Likewise, animals that lack the caspase-8 adaptor FADD or FLIP, which resembles caspase-8 but lacks a catalytic site (Wilson et al. 2009), also die at E10.5. The Clap1−/−Clap2−/− double knockout mice are partially rescued to birth (but not beyond) by crossing them to Tnfr1−/− mice (Moulin et al. 2012), demonstrating that the cIAPs regulate a developmentally important TNF-R1 signaling pathway at E10.5 and suggesting that caspase-8, FADD, and cFLIP are likewise involved in this pathway. Embryonic lethality is also partially rescued by crossing the Xiap−/−Clap1−/− and Clap1−/−Clap2−/− mice to Ripk1−/− and Ripk3−/− mice (Moulin et al. 2012), showing that these IAPs function together as critical regulators of an embryonic decision point involving RIP kinase activity. Consistently, recent evidence indicates that XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 together control the assembly of an upstream cell-death-inducing platform dubbed the “Ripoptosome” (also referred to as Complex-II and Necrosome) (Fig. 5). The Ripoptosome assembles in response to simultaneous genetic deletion of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2, or in response to SM treatment. It can also form following genotoxic stress-induced depletion of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2. This large ∼2MDa macromolecular complex contains the core components RIPK1, FADD, and caspase-8, and can stimulate caspase-8-mediated apoptosis as well as caspase-independent necrosis. The Ripoptosome can also include additional proteins such as caspase-10, cFLIPL, RIPK3, and TRIF, depending on cell type and stimulus. Assembly of the Ripoptosome depends on the kinase activity of RIPK1. It is negatively regulated by cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP, as well as cFLIP. Among the IAPs, cIAP1 and cIAP2 are the most critical regulators of Ripoptosome assembly (Geserick et al. 2009; Feoktistova et al. 2011; Tenev et al. 2011a). Nevertheless, XIAP also contributes to the regulation of this RIPK1-based platform because in the absence of XIAP, depletion of cIAPs results in increased assembly of this complex. The extent to which individual IAPs contribute to the inhibition of Ripoptosome assembly will, most likely, depend on cell type and stimulus. IAP-mediated inactivation of RIPK1 and/or Ripoptosome occurs in an Ub-dependent manner, most likely by targeting RIPK1 and other components of the Ripoptosome for proteasomal degradation. Caspase-8-mediated cleavage of cFLIP leads to the generation of cFLIP(p43), which allows its binding to TRAF2 and the formation of a cFLIP(p43)-caspase-8-TRAF2 tertiary complex (Micheau et al. 2002; Kataoka and Tschopp 2004). TRAF2 then recruits cIAPs, which target cleaved cFLIP and caspase-8 for ubiquitylation (Tenev et al. 2011b). This indicates that cIAP1 and cIAP2 target “active” cFLIP-caspase-8 complexes for ubiquitylation and inactivation.

Figure 5.

cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP prevent the formation of a RIPK1-dependent platform, dubbed the Ripoptosome, Necrosome, or Complex-II. (A) All three IAPs target RIPK1 and components of the Ripoptosome (caspase-8 and cFLIPL) for Ub-mediated inactivation. Following genotoxic stress, cytokine signaling-induced depletion of cIAPs, or SM treatment, cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP levels rapidly decline and/or are inactivated. This allows formation and accumulation of the Ripoptosome. In the presence of high levels of RIPK3, this can lead to necroptosis. cFLIP also regulates Ripoptosome-mediated cell death. cFLIPL thereby prevents apoptosis and necroptosis, whereas FLIPS inhibits apoptosis but promotes necroptosis. (B) Under steady-state conditions, the majority of RIPK1 appears to be in a closed configuration that prevents it from binding to partner proteins. Cytokine receptor stimulation can convert a small fraction of RIPK1 into an “open,” binding-competent configuration. In the presence of cIAPs and XIAP, binding-competent RIPK1 is targeted for Ub-mediated inactivation, most likely via proteasomal degradation. Under conditions where IAP levels are low, however, unmodified and binding-competent RIPK1 accumulates and can form the Ripoptosome. In the presence of high levels of cFLIPL, the Ripoptosome is dissolved via caspase-8-cFLIPL-mediated cleavage of RIPK1. When cFLIPL levels are low, the Ripoptosome can promote caspase-dependent or caspase-independent cell death.

Even though SM-mediated inhibition of cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP does not necessarily lead to immediate cell death, SM-induced assembly of the Ripoptosome can prime cells for death (Geserick et al. 2009; Feoktistova et al. 2011; Tenev et al. 2011b). For example, Fas signaling in resistant cells can be converted to a prodeath stimulus by SM treatment that leads to formation of an RIPK1-containing cell-death-inducing complex (Geserick et al. 2009). Likewise, activation of TLR3 (which normally signals for inflammatory responses through NF-κB and type-I interferon induction) in the presence of SM (or absence of cIAPs), leads to Ripoptosome-mediated cell death (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the proinflammatory cytokines TNF, TWEAK, and LIGHT trigger Ripoptosome-mediated cell death in the presence of SM or genotoxic stress-mediated depletion of IAPs. This suggests that mere inactivation of IAPs is not sufficient to induce cell death. For death to occur, an additional “RIPK1-activating” signal is required. This can be provided in the form of DNA damage or cytokine signaling (Fig. 5B).

The Ripoptosome can also mediate caspase-independent necroptosis. This form of death depends on the presence of RIPK3 and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Vandenabeele et al. 2010). Interestingly, different isoforms of cFLIP determine whether the Ripoptosome induces RIPK3-dependent necroptosis or caspase-mediated apoptosis (Geserick et al. 2009; Feoktistova et al. 2011; Tenev et al. 2011b). Whereas cFLIPL can protect cells against both forms of cell death, cFLIPS actively promotes RIP-dependent necroptosis while blocking apoptosis. This paradoxical role of the different isoforms of cFLIP is likely due to the fact that cFLIPL limits recruitment of RIPK1 into the Ripoptosome and allows localized activation of caspase-8, which results in cleavage and inactivation of RIPK1 and CYLD (O’Donnell and Ting 2011; Pop et al. 2011) and suppression of necroptotic cell death. This observation also provides a mechanistic explanation why genetic deletion of FADD, FLIPL, or caspase-8 causes embryonic lethality. Although caspase-8- and FADD-deficient mice die at embryonic stage 10.5, they are rescued, at least in part, by co-deletion of RIPK1 and RIPK3 (Kaiser et al. 2011; Oberst et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2011). Therefore, caspase-8 appears to be required to suppress caspase-independent necroptosis. It is not known presently how caspase-8 is activated to regulate RIPK-dependent necrosis.

IAP-Mediated Regulation of Innate Immunity and Cell Survival

In addition to controlling the assembly and activity of caspase-activating platforms, IAPs also contribute to cell survival by regulating NF-κB signal transduction and innate immune responses (Damgaard and Gyrd-Hansen 2011). NF-κB transcription factors are important regulators of the genes necessary for innate and adaptive immune responses and for the survival and proliferation of certain cell types (Karin and Greten 2005). The realization that IAPs function as critical components of NF-κB signal transduction first came from Drosophila where DIAP2 was found to be essential to fend off Gram-negative bacterial infection (Gesellchen et al. 2005; Kleino et al. 2005; Leulier et al. 2006a; Huh et al. 2007). In Drosophila, infection by Gram-negative bacteria triggers the innate immune response by activating the immune deficiency (IMD) signaling cascade (Lemaitre and Hoffmann 2007), a Rel/NF-κB-dependent pathway that shares striking similarities with mammalian tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1) (Tanji and Ip 2005). diap2 mutant flies fail to activate NF-κB-mediated expression of antibacterial peptide genes and, consequently, rapidly succumb to bacterial infection (Leulier et al. 2006a; Huh et al. 2007). DIAP2-mediated signaling to NF-κB critically depends on its Ub-E3 ligase activity (Leulier et al. 2006a; Huh et al. 2007; Paquette et al. 2010; Meinander et al. 2012). In conjunction with the E2 Ub-conjugating enzymes Effete (UBC5) and UEV1a/Bendless (UEV1a/Ubc13) (Zhou et al. 2005; Paquette et al. 2010), DIAP2 promotes the conjugation of K63-linked Ub chains on IMD and DREDD (also referred to as DCP-2) (Paquette et al. 2010; Meinander et al. 2012), the Drosophila ortholog of caspase-8. Activation of the pattern-recognition receptor PGRP-LCx triggers recruitment of IMD, DREDD, and dFADD (also referred to as BG4). Recruitment of DIAP2 targets DREDD for K63-linked ubiquitylation, which allows Ub-mediated aggregation and activation of DREDD (Meinander et al. 2012). Active DREDD subsequently cleaves IMD (Paquette et al. 2010). Upon cleavage, IMD exposes an IBM at its neo-NH2 terminus, which binds to the BIR2/3 of DIAP2. This provides DIAP2 with an additional docking site, reinforcing complex stability and allowing DIAP2-mediated ubiquitylation of IMD, and quite possibly other components of the signaling complex (Paquette et al. 2010). The Ub chains on IMD and DREDD appear to serve as scaffolds for the recruitment of dTAK1, IKK, and the precursor form of the NF-κB transcription factor Relish (Rutschmann et al. 2000, 2002; Silverman et al. 2000, 2003; Lu et al. 2001; Vidal et al. 2001; Kanayama et al. 2004; Kleino et al. 2005; Zhuang et al. 2006; Ferrandon et al. 2007). This brings Relish into close proximity of ubiquitylated and active DREDD, allowing DREDD-mediated proteolysis of Relish. The proximity to the signaling complex also allows phospho-mediated activation of Relish (Erturk-Hasdemir et al. 2009). Subsequently, cleaved and phosphoryated Relish translocates to the nucleus where it drives expression of antimicrobial peptide genes.

IAP-mediated activation of NF-κB also occurs in mammals. cIAP1 and cIAP2 are required for canonical activation of NF-κB and MAPK by members of the TNF-receptor family (Mahoney et al. 2008; Varfolomeev et al. 2008). For instance, binding of trimeric TNF to TNF-R1 triggers the initial recruitment of the adaptor proteins TRADD, TRAF2, the E3 ligases, cIAP1 and cIAP2, and the protein kinase RIPK1 (Fig. 6). This complex is frequently referred to as Complex-I (Micheau and Tschopp 2003). cIAP-mediated conjugation of Ub to components of Complex-I, such as RIPK1, allows subsequent recruitment of the linear Ub chain assembly complex (LUBAC, composed of HOIL/HOIP/Sharpin), the kinase complexes (composed of TAK1/TAB2/TAB3), and IKK (composed of NEMO/IKKα/IKKβ) (Silke 2011). This mechanism of Complex-I assembly is well established for some cell types, and the molecular interactions between TRADD, TRAF2, and cIAPs have been revealed by crystallography, as depicted schematically in Figure 6. It is worth remarking, however, that neither TRADD nor RIPK1 are essential components for Complex-I-mediated activation of NF-κB in all cells (Chen et al. 2008; Ermolaeva et al. 2008; Pobezinskaya et al. 2008; Wong et al. 2010). In stark contrast, cIAPs are indispensable for TNF-induced activation of NF-κB in all cell types tested so far (Mahoney et al. 2008; Varfolomeev et al. 2008; Haas et al. 2009). Ub-dependent recruitment of LUBAC, TAK1/TAB2/TAB3, and IKKs is mediated by UBDs present in TAB2, NEMO, and HOIP. Once recruited, LUBAC then modifies NEMO and RIPK1 with M1-linked Ub chains, resulting in increased stability of the TNF signaling complex. Additionally, the binding of NEMO to M1-linked Ub chains causes a conformational change of the IKK complex that is thought to facilitate its activation (Rahighi et al. 2009). Following activation, IKKβ phosphorylates IκBα, which targets it for K48-linked ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation. Depletion of IκB liberates NF-κB dimers, which subsequently translocate to the nucleus and drive expression of target genes. Loss of LUBAC components markedly impairs, but does not abolish, Complex-I mediated signaling (Haas et al. 2009; Tokunaga et al. 2009, 2011; Gerlach et al. 2011; Ikeda et al. 2011). Therefore, it seems likely that cIAPs, and cIAP-mediated ubiquitylation, are sufficient for limited activation of genes important for inflammation and cell survival. Perhaps, the newly described K11-linked Ub chains that can be generated by cIAPs and that can recruit NEMO (Dynek et al. 2010) might contribute to this partial NF-κB activity. cIAPs are also required for JNK signaling (Matsuzawa et al. 2008; Gardam et al. 2011). This has been most clearly demonstrated for signaling that emanates from CD40, a TNF-superfamily receptor, but similar concepts likely hold true for TNF-R1 signaling too.

Figure 6.

TNF signaling is regulated by cIAPs. (A) Upon TNF-binding, cIAPs are recruited to the TNF-R1 signaling complex (Complex-I) via TRADD/TRAF2. The cIAP RING dimerizes, which leads to activation of its E3 activity. Active cIAPs ubiquitylate several molecules within the complex. RIPK1 ubiquitylation is the most readily observed, and is absent in SM-treated or cIAP knockout cells. Of note, although TNF-induced ubiquitylation of RIPK1 is a prominent event, RIPK1 is not required for TNF signaling in all cells. Ubiquitylation of components of Complex-I, such as RIP, drives the recruitment of HOIL-1/HOIP/Sharpin that together form the linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC). LUBAC generates linear Ub chains on NEMO and RIPK1, which in turn recruits more NEMO molecules via its linear Ub-binding UBAN domain. NEMO is probably constitutively associated with IKKα/IKKβ, and IKKβ is phosphorylated and activated by TAK1 that is independently recruited to ubiquitylated Complex-I via its Ub receptors TAB2 and TAB3, which bind only to K63-linked Ub chains. Phosphorylated and activated IKKβ in turn phosphorylates IκBα, which leads to recruitment of a HECT E3 ligase. This E3 ligase promotes K48-linked ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of IκBα, allowing translocation of NF-κB subunits p50 and p65 to drive production of cytokines. p50 and p65 also promote expression of IκBα to cause feedback inhibition, as well as genes such as cFLIP that are required to protect cells from Complex-II-induced cell death. The numbered arrows provide a tentative indication of temporal sequence. Complex-II is most likely generated from Complex-I, in an as yet undefined manner, and comprises FADD and caspase-8. cIAPs and LUBAC appear to limit Complex-II formation by promoting ubiquitylation-mediated degradation of Complex-II components. Caspase-8 limits Complex-II formation by cleaving and inactivating RIPK1. Therefore, loss of IAPs, LUBAC, or caspase-8 activity results in formation of Complex-II*, which is able to drive necroptosis. (B) Schematic diagram depicting NOD-mediated signaling. Upon stimulation of NOD1 or NOD2 by their respective ligands (DAP and MDP), a similar signaling complex to that of TNF-R1 is assembled. However, whereas cIAPs are critical regulators of TNF-R1 signaling, XIAP plays a key role in NOD-mediated activation of NF-κB and MAPK. XIAP, thereby, allows signaling by targeting NOD-bound RIPK2 for ubiquitylation.

cIAPs are also required for constitutive suppression of the noncanonical NF-κB pathways (Varfolomeev et al. 2007; Vince et al. 2007). Activation of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway occurs in response to ligands of a subset of the TNF receptor superfamily that includes BAFF, CD40 L, and TWEAK. Under unstimulated conditions, noncanonical NF-κB signaling is normally suppressed because of the constitutive proteasomal degradation of the kinase NIK by a Ub E3 ligase complex consisting of TRAF2, TRAF3, and cIAPs (Varfolomeev et al. 2007; Vince et al. 2007; Vallabhapurapu et al. 2008; Zarnegar et al. 2008). TRAF3 binds directly to NIK and recruits it to TRAF2 through its ability to heterodimerize with TRAF2. TRAF2 in turn recruits cIAP1 or cIAP2, which are responsible for the conjugation of K48-linked Ub chains to NIK. While cIAPs constitutively shut down noncanonical NF-κB signaling, activation of this pathway is triggered upon ligation of BAFF, CD40 L, and TWEAK. Receptor ligation results in the recruitment of TRAF3-TRAF2-cIAP to the receptor complex. This causes ubiquitylation and degradation of TRAF3 or coordinated depletion of TRAF2 and cIAP1, depending on cellular context and the receptor involved (Varfolomeev et al. 2007; Vince et al. 2007). Irrespective of the mechanism of depletion, loss of any of the components of the TRAF3-TRAF2-cIAP E3 complex results in stabilization of NIK. Stabilization of NIK results in its activation, whereupon it phophorylates and activates IKKα and the NF-κB precursor p100 (Xiao et al. 2001). Activated IKKα homodimers phosphorylate additional residues in p100, which leads to its partial degradation to generate the p52 form. Genetic loss of TRAF2, TRAF3, or cIAPs also results in accumulation of NIK and constitutive activation of noncanonical NF-κB signaling, which drives cell survival and inflammatory responses. Moreover, cIAPs, and to some extent XIAP, also regulate NF-κB activation downstream of other innate immunity platforms such as the ones assembled by toll-like receptors (TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4), nucleotide-binding oligomerization-domain protein-like receptors (NOD1 and NOD2), and RIG-I (Yang et al. 2007; Hasegawa et al. 2008; Bertrand et al. 2009; Krieg et al. 2009; Damgaard and Gyrd-Hansen 2011).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The realization that alterations in IAPs are found in many types of human cancer and are associated with chemoresistance, disease progression, and poor prognosis has sparked renewed interest in a better understanding of IAP biology. It is now clear that IAPs contribute to cell survival at multiple levels, controlling the formation of cell-death-activating platforms, such as the apoptosome in Drosophila and the Ripoptosome in mammals, as well as by mediating activation of NF-κB and induction of prosurvival transcriptional programs. Both these processes rely on the ability of IAPs to function as E3 ligases, placing them at the intersection of the Ub-conjugation system, regulation of cell death, and inflammation. Clearly, a deeper understanding of IAP biology, and the constellations in which inhibition of IAP function is beneficial, is needed to limit the potential effects of erroneous sensitization to apoptosis, inadvertent generation of chronic inflammation, and/or defects in innate immune signaling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our apologies to those whose work could not be cited or were cited only indirectly owing to space limitations. We would like to thank members of the Meier and Silke Labs for support. We acknowledge NHS funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support, and Australian Government NHMRC and NHMRC IRIISS funding.

Footnotes

Editors: Eric H. Baehrecke, Douglas R. Green, Sally Kornbluth, and Guy S. Salvesen

Additional Perspectives on Cell Survival and Cell Death available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Arama E, Agapite J, Steller H 2003. Caspase activity and a specific cytochrome C are required for sperm differentiation in Drosophila. Dev Cell 4: 687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartke T, Pohl C, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S 2004. Dual role of BRUCE as an antiapoptotic IAP and a chimeric E2/E3 ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell 14: 801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AB, Witte MD, Denault JB, Sadaghiani AM, Sexton KM, Salvesen GS, Bogyo M 2006. Identification of early intermediates of caspase activation using selective inhibitors and activity-based probes. Mol Cell 23: 509–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand MJ, Doiron K, Labbe K, Korneluk RG, Barker PA, Saleh M 2009. Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis cIAP1 and cIAP2 are required for innate immunity signaling by the pattern recognition receptors NOD1 and NOD2. Immunity 30: 789–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoj VG, Chen ZJ 2009. Ubiquitylation in innate and adaptive immunity. Nature 458: 430–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum MJ, Clem RJ, Miller LK 1994. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motifs. J Virol 68: 2521–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broemer M, Tenev T, Rigbolt KT, Hempel S, Blagoev B, Silke J, Ditzel M, Meier P 2010. Systematic in vivo RNAi analysis identifies IAPs as NEDD8-E3 ligases. Mol Cell 40: 810–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J, Yan N, Huh JR, Wu JW, Li W, Hay BA, Shi Y 2003. Molecular mechanism of Reaper-Grim-Hid-mediated suppression of DIAP1-dependent Dronc ubiquitination. Nat Struct Biol 10: 892–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ 2012. Ubiquitination in signaling to and activation of IKK. Immunol Rev 246: 95–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NJ, Chio II, Lin WJ, Duncan G, Chau H, Katz D, Huang HL, Pike KA, Hao Z, Su YW, et al. 2008. Beyond tumor necrosis factor receptor: TRADD signaling in toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 12429–12434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook NE, Clem RJ, Miller LK 1993. An apoptosis inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger like motif. J Virol 67: 2168–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard RB, Gyrd-Hansen M 2011. Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins in regulation of inflammation and innate immunity. Discov Med 11: 221–231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denault JB, Bekes M, Scott FL, Sexton KM, Bogyo M, Salvesen GS 2006. Engineered hybrid dimers: Tracking the activation pathway of caspase-7. Mol Cell 23: 523–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC 1997. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature 388: 300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel M, Meier P 2005. Ubiquitylation in apoptosis: DIAP1’s (N-)en(d)igma. Cell Death Differ 12: 1208–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel M, Wilson R, Tenev T, Zachariou A, Paul A, Deas E, Meier P 2003. Degradation of DIAP1 by the N-end rule pathway is essential for regulating apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 5: 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel M, Broemer M, Tenev T, Bolduc C, Lee TV, Rigbolt KT, Elliott R, Zvelebil M, Blagoev B, Bergmann A, et al. 2008. Inactivation of effector caspases through nondegradative polyubiquitylation. Mol Cell 32: 540–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues C, Ryoo HD 2012. Drosophila BRUCE inhibits apoptosis through non-lysine ubiquitination of the IAP-antagonist REAPER. Cell Death Differ 19: 470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueber EC, Schoeffler AJ, Lingel A, Elliott JM, Fedorova AV, Giannetti AM, Zobel K, Maurer B, Varfolomeev E, Wu P, et al. 2011. Antagonists induce a conformational change in cIAP1 that promotes autoubiquitination. Science 334: 376–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynek JN, Goncharov T, Dueber EC, Fedorova AV, Izrael-Tomasevic A, Phu L, Helgason E, Fairbrother WJ, Deshayes K, Kirkpatrick DS, et al. 2010. c-IAP1 and UbcH5 promote K11-linked polyubiquitination of RIP1 in TNF signalling. EMBO J 29: 4198–4209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman BP, Salvesen GS, Scott FL 2006. Human inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: Why XIAP is the black sheep of the family. EMBO Rep 7: 988–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolaeva MA, Michallet MC, Papadopoulou N, Utermohlen O, Kranidioti K, Kollias G, Tschopp J, Pasparakis M 2008. Function of TRADD in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and in TRIF-dependent inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol 9: 1037–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erturk-Hasdemir D, Broemer M, Leulier F, Lane WS, Paquette N, Hwang D, Kim CH, Stoven S, Meier P, Silverman N 2009. Two roles for the Drosophila IKK complex in the activation of Relish and the induction of antimicrobial peptide genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 9779–9784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltham R, Bettjeman B, Budhidarmo R, Mace PD, Shirley S, Condon SM, Chunduru SK, McKinlay MA, Vaux DL, Silke J, et al. 2011. SMACmimetics activate the E3 ligase activity of cIAP1 by promoting RING dimerisation. J Biol Chem 286: 17015–17028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Kellert B, Dimitrova DP, Langlais C, Hupe M, Cain K, MacFarlane M, Hacker G, Leverkus M 2011. cIAPs block Ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8 containing intracellular cell death complex differentially regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol Cell 43: 449–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D, Imler JL, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA 2007. The Drosophila systemic immune response: sensing and signalling during bacterial and fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 862–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardam S, Turner VM, Anderton H, Limaye S, Basten A, Koentgen F, Vaux DL, Silke J, Brink R 2011. Deletion of cIAP1 and cIAP2 in murine B lymphocytes constitutively activates cell survival pathways and inactivates the germinal center response. Blood 117: 4041–4051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentle IE, Wong WW, Evans JM, Bankovacki A, Cook WD, Khan NR, Nachbur U, Rickard J, Anderton H, Moulin M, et al. 2011. In TNF-stimulated cells, RIPK1 promotes cell survival by stabilizing TRAF2 and cIAP1, which limits induction of non-canonical NF-κB and activation of caspase-8. J Biol Chem 286: 13282–13291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach B, Cordier SM, Schmukle AC, Emmerich CH, Rieser E, Haas TL, Webb AI, Rickard JA, Anderton H, Wong WW, et al. 2011. Linear ubiquitination prevents inflammation and regulates immune signalling. Nature 471: 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesellchen V, Kuttenkeuler D, Steckel M, Pelte N, Boutros M 2005. An RNA interference screen identifies Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein 2 as a regulator of innate immune signaling in Drosophila. EMBO Rep 6: 979–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geserick P, Hupe M, Moulin M, Wong WW, Feoktistova M, Kellert B, Gollnick H, Silke J, Leverkus M 2009. Cellular IAPs inhibit a cryptic CD95-induced cell death by limiting RIP1 kinase recruitment. J Cell Biol 187: 1037–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal L, McCall K, Agapite J, Hartwieg E, Steller H 2000. Induction of apoptosis by Drosophila reaper, hid and grim through inhibition of IAP function. EMBO J 19: 589–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyrd-Hansen M, Meier P 2010. IAPs: From caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-κB, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas TL, Emmerich CH, Gerlach B, Schmukle AC, Cordier SM, Rieser E, Feltham R, Vince J, Warnken U, Wenger T, et al. 2009. Recruitment of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex stabilizes the TNF-R1 signaling complex and is required for TNF-mediated gene induction. Mol Cell 36: 831–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Sekine K, Kawabata A, Nakamura H, Ishioka T, Ohata H, Katayama R, Hashimoto C, Zhang X, Noda T, et al. 2004. Apollon ubiquitinates SMAC and caspase-9, and has an essential cytoprotection function. Nat Cell Biol 6: 849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Fujimoto Y, Lucas PC, Nakano H, Fukase K, Nunez G, Inohara N 2008. A critical role of RICK/RIP2 polyubiquitination in Nod-induced NF-κB activation. EMBO J 27: 373–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay BA, Wassarman DA, Rubin GM 1995. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell 83: 1253–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Bachinsky Y, Ryoo HD, Ciechanover A, Gonen H 2007. Regulation of the Drosophila ubiquitin ligase DIAP1 is mediated via several distinct ubiquitin system pathways. Cell Death Differ 14: 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeller D, Hecker CM, Dikic I 2006. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 6: 776–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh JR, Foe I, Muro I, Chen CH, Seol JH, Yoo SJ, Guo M, Park JM, Hay BA 2007. The Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) DIAP2 is dispensable for cell survival, required for the innate immune response to Gram-negative bacterial infection, and can be negatively regulated by the reaper/hid/grim family of IAP-binding apoptosis inducers. J Biol Chem 282: 2056–2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F, Deribe YL, Skanland SS, Stieglitz B, Grabbe C, Franz-Wachtel M, van Wijk SJ, Goswami P, Nagy V, Terzic J, et al. 2011. SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature 471: 637–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Vucic D, Miller LK 1998. The Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis D-IAP1 suppresses cell death induced by the caspase drICE. FEBS Lett 440: 243–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, Caspary T, Mocarski ES 2011. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature 471: 368–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama A, Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Hong M, Shaito A, Chiu YH, Deng L, Chen ZJ 2004. TAB2 and TAB3 activate the NF-κB pathway through binding to polyubiquitin chains. Mol Cell 15: 535–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Greten FR 2005. NF-κB: Linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka T, Tschopp J 2004. N-terminal fragment of c-FLIP(L) processed by caspase 8 specifically interacts with TRAF2 and induces activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2627–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Kamei K, Murata S, Kato M, Fukumoto H, Kanie M, Sano S, Tokunaga F, Tanaka K, Iwai K 2006. A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J 25: 4877–4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleino A, Valanne S, Ulvila J, Kallio J, Myllymaki H, Enwald H, Stoven S, Poidevin M, Ueda R, Hultmark D, et al. 2005. Inhibitor of apoptosis 2 and TAK1-binding protein are components of the Drosophila Imd pathway. EMBO J 24: 3423–3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D 2009. The emerging complexity of protein ubiquitination. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 937–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D, Rape M 2012. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem 81: 203–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg A, Correa RG, Garrison JB, Le Negrate G, Welsh K, Huang Z, Knoefel WT, Reed JC 2009. XIAP mediates NOD signaling via interaction with RIP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 14524–14529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCasse EC, Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Plenchette S, Baird S, Korneluk RG 2008. IAP-targeted therapies for cancer. Oncogene 27: 6252–6275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J 2007. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol 25: 697–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leulier F, Lhocine N, Lemaitre B, Meier P 2006a. The Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis protein DIAP2 functions in innate immunity and is essential to resist Gram-negative bacterial infection. Mol Cell Biol 26: 7821–7831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leulier F, Ribeiro PS, Palmer E, Tenev T, Takahashi K, Robertson D, Zachariou A, Pichaud F, Ueda R, Meier P 2006b. Systematic in vivo RNAi analysis of putative components of the Drosophila cell death machinery. Cell Death Differ 13: 1663–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisi S, Mazzon I, White K 2000. Diverse domains of THREAD/DIAP1 are required to inhibit apoptosis induced by REAPER and HID in Drosophila. Genetics 154: 669–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J, Wicky Joh S, Tenev T, Tautureau GJP, Hinds MG, Francalanci F, Wilson R, Broemer M, Santoro MM, Day CL, et al. 2011. CARD-mediated autoinhibition of cIAP1’s E3 ligase activity suppresses cell proliferation and migration. Mol Cell 42: 569–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Wu LP, Anderson KV 2001. The antibacterial arm of the Drosophila innate immune response requires an IκB kinase. Genes Dev 15: 104–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Lin SC, Huang Y, Kang YJ, Rich R, Lo YC, Myszka D, Han J, Wu H 2007. XIAP induces NF-B activation via the BIR1/TAB1 interaction and BIR1 dimerization. Mol Cell 26: 689–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace PD, Linke K, Feltham R, Schumacher FR, Smith CA, Vaux DL, Silke J, Day CL 2008. Structures of the cIAP2 RING domain reveal conformational changes associated with ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) recruitment. J Biol Chem 283: 31633–31640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Mrad RL, Plenchette S, Simard C, Enwere E, Arora V, Mak TW, Lacasse EC, Waring J, et al. 2008. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 11778–11783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo E, Cossu F, Milani M, Sorrentino G, Lecis D, Delia D, Manzoni L, Drago C, Seneci P, Scolastico C, et al. 2008. Targeting the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein through 4-substituted azabicyclo[5.3.0]alkane smac mimetics. Structure, activity, and recognition principles. J Mol Biol 384: 673–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa A, Tseng PH, Vallabhapurapu S, Luo JL, Zhang W, Wang H, Vignali DA, Gallagher E, Karin M 2008. Essential cytoplasmic translocation of a cytokine receptor-assembled signaling complex. Science 321: 663–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier P, Silke J, Leevers SJ, Evan GI 2000. The Drosophila caspase DRONC is regulated by DIAP1. EMBO J 19: 598–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinander A, Runchel C, Tenev T, Chen L, Kim CH, Ribeiro PS, Broemer M, Leulier F, Zvelebil M, Silverman N, et al. 2012. Ubiquitylation of the initiator caspase DREDD is required for innate immune signalling. EMBO J 31: 2770–2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O, Tschopp J 2003. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell 114: 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O, Thome M, Schneider P, Holler N, Tschopp J, Nicholson DW, Briand C, Grutter MG 2002. The long form of FLIP is an activator of caspase-8 at the Fas death-inducing signaling complex. J Biol Chem 277: 45162–45171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin M, Anderton H, Voss AK, Thomas T, Wong WW, Bankovacki A, Feltham R, Chau D, Cook WD, Silke J, et al. 2012. IAPs limit activation of RIP kinases by TNF receptor 1 during development. EMBO J 31: 1679–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, Hakem R, Salvesen GS, Green DR 2011. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature 471: 363–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell MA, Ting AT 2011. RIP1 comes back to life as a cell death regulator in TNFR1 signaling. FEBS J 278: 877–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette N, Broemer M, Aggarwal K, Chen L, Husson M, Erturk-Hasdemir D, Reichhart JM, Meier P, Silverman N 2010. Caspase-mediated cleavage, IAP binding, and ubiquitination: Linking three mechanisms crucial for Drosophila NF-κB signaling. Mol Cell 37: 172–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobezinskaya YL, Kim YS, Choksi S, Morgan MJ, Li T, Liu C, Liu Z 2008. The function of TRADD in signaling through tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and TRIF-dependent toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 9: 1047–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl C, Jentsch S 2008. Final stages of cytokinesis and midbody ring formation are controlled by BRUCE. Cell 132: 832–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop C, Oberst A, Drag M, Van Raam BJ, Riedl SJ, Green DR, Salvesen GS 2011. FLIP(L) induces caspase 8 activity in the absence of interdomain caspase 8 cleavage and alters substrate specificity. Biochem J 433: 447–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahighi S, Ikeda F, Kawasaki M, Akutsu M, Suzuki N, Kato R, Kensche T, Uejima T, Bloor S, Komander D, et al. 2009. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by NEMO is important for NF-κB activation. Cell 136: 1098–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro PS, Kuranaga E, Tenev T, Leulier F, Miura M, Meier P 2007. DIAP2 functions as a mechanism-based regulator of drICE that contributes to the caspase activity threshold in living cells. J Cell Biol 179: 1467–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl SJ, Shi Y 2004. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 897–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Oliver H, Zou H, Chen P, Wang X, Abrams JM 1999. Dark is a Drosophila homologue of Apaf-1/CED-4 and functions in an evolutionarily conserved death pathway. Nat Cell Biol 1: 272–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutschmann S, Jung AC, Zhou R, Silverman N, Hoffmann JA, Ferrandon D 2000. Role of Drosophila IKKγ in a toll-independent antibacterial immune response. Nat Immunol 1: 342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutschmann S, Kilinc A, Ferrandon D 2002. Cutting edge: The toll pathway is required for resistance to Gram-positive bacterial infections in Drosophila. J Immunol 168: 1542–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen GS, Duckett CS 2002. Apoptosis: IAP proteins: Blocking the road to death’s door. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel T, Welsh K, Lober T, Togo SH, et al. 2006. Distinct BIR domains of cIAP1 mediate binding to and ubiquitination of TRAF2 and Smac. J Biol Chem 281: 1080–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmukle AC, Walczak H 2012. No one can whistle a symphony alone: How different ubiquitin linkages cooperate to orchestrate NF-κB activity. J Cell Sci 125: 549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro PJ, Hsu HH, Jung H, Robbins ES, Ryoo HD 2008. Regulation of the Drosophila apoptosome through feedback inhibition. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1440–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silke J 2011. The regulation of TNF signaling: What a tangled web we weave. Curr Opin Immunol 23: 620–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N, Zhou R, Stoven S, Pandey N, Hultmark D, Maniatis T 2000. A Drosophila IκB kinase complex required for Relish cleavage and antibacterial immunity. Genes Dev 14: 2461–2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N, Zhou R, Erlich RL, Hunter M, Bernstein E, Schneider D, Maniatis T 2003. Immune activation of NF-κB and JNK requires Drosophila TAK1. J Biol Chem 278: 48928–48934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula SM, Ashwell JD 2008. IAPs: What’s in a name? Mol Cell 30: 123–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji T, Ip YT 2005. Regulators of the Toll and Imd pathways in the Drosophila innate immune response. Trends Immunol 26: 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Zachariou A, Wilson R, Ditzel M, Meier P 2005. IAPs are functionally non-equivalent and regulate effector caspases through distinct mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol 7: 70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Ditzel M, Zachariou A, Meier P 2007. The antiapoptotic activity of insect IAPs requires activation by an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Death Differ 14: 1191–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Bianchi K, Darding M, Broemer M, Langlais C, Wallberg F, Zachariou A, Lopez J, MacFarlane M, Cain K, et al. 2011a. The Ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol Cell 43: 432–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Bianchi K, Darding M, Broemer M, Langlais C, Wallberg F, Zachariou A, Lopez J, Macfarlane M, Cain K, et al. 2011b. The Ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol Cell 43: 432–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga F, Sakata S, Saeki Y, Satomi Y, Kirisako T, Kamei K, Nakagawa T, Kato M, Murata S, Yamaoka S, et al. 2009. Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-κB activation. Nat Cell Biol 11: 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga F, Nakagawa T, Nakahara M, Saeki Y, Taniguchi M, Sakata S, Tanaka K, Nakano H, Iwai K 2011. SHARPIN is a component of the NF-κB-activating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Nature 471: 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren AG, Beilharz T, O’Connell MJ, Bugg SJ, van Driel R, Vaux DL, Lithgow T 1999. Role for yeast inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP)-like proteins in cell division. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 10170–10175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren AG, Wong L, Pakusch M, Fowler KJ, Burrows FJ, Vaux DL, Choo KH 2000. Survivin and the inner centromere protein INCENP show similar cell-cycle localization and gene knockout phenotype. Curr Biol 10: 1319–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Matsuzawa A, Zhang W, Tseng PH, Keats JJ, Wang H, Vignali DA, Bergsagel PL, Karin M 2008. Nonredundant and complementary functions of TRAF2 and TRAF3 in a ubiquitination cascade that activates NIK-dependent alternative NF-κB signaling. Nat Immunol 9: 1364–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe T, Kroemer G 2010. Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: An ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 700–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev E, Wayson SM, Dixit VM, Fairbrother WJ, Vucic D 2006. The inhibitor of apoptosis protein fusion c-IAP2.MALT1 stimulates NF-κB activation independently of TRAF1 and TRAF2. J Biol Chem 281: 29022–29029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, Zobel K, Dynek JN, Elliott LO, Wallweber HJ, et al. 2007. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-κB activation, and TNFα-dependent apoptosis. Cell 131: 669–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev E, Goncharov T, Fedorova AV, Dynek JN, Zobel K, Deshayes K, Fairbrother WJ, Vucic D 2008. c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 are critical mediators of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-induced NF-κB activation. J Biol Chem 283: 24295–24299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen AM, Kratina TK, Hawkins CJ, Silke J, Ekert PG, Vaux DL 2007. Identification of mammalian mitochondrial proteins that interact with IAPs via N-terminal IAP binding motifs. Cell Death Differ 14: 348–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooy SY, Chow V, Su J, Verbrugghe K, Yang J, Cole S, Olson MR, Hay BA 2002. Drosophila Bruce can potently suppress Rpr- and Grim-dependent but not Hid-dependent cell death. Curr Biol 12: 1164–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal S, Khush RS, Leulier F, Tzou P, Nakamura M, Lemaitre B 2001. Mutations in the Drosophila dTAK1 gene reveal a conserved function for MAPKKKs in the control of rel/NF-κB-dependent innate immune responses. Genes Dev 15: 1900–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince JE, Wong WW, Khan N, Feltham R, Chau D, Ahmed AU, Benetatos CA, Chunduru SK, Condon SM, McKinlay M, et al. 2007. IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFα-dependent apoptosis. Cell 131: 682–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SL, Hawkins CJ, Yoo SJ, Muller HA, Hay BA 1999. The Drosophila caspase inhibitor DIAP1 is essential for cell survival and is negatively regulated by HID. Cell 98: 453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Goyal L, Ditzel M, Zachariou A, Baker DA, Agapite J, Steller H, Meier P 2002. The DIAP1 RING finger mediates ubiquitination of Dronc and is indispensable for regulating apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 4: 445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NS, Dixit V, Ashkenazi A 2009. Death receptor signal transducers: Nodes of coordination in immune signaling networks. Nat Immunol 10: 348–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WW, Gentle IE, Nachbur U, Anderton H, Vaux DL, Silke J 2010. RIPK1 is not essential for TNFR1-induced activation of NF-κB. Cell Death Differ 17: 482–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Chai J, Suber TL, Wu JW, Du C, Wang X, Shi Y 2000. Structural basis of IAP recognition by Smac/DIABLO. Nature 408: 1008–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Sun SC 2001. NF-κB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-κB2 100. Mol Cell 7: 401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Yin C, Pandey A, Abbott D, Sassetti C, Kelliher MA 2007. NOD2 pathway activation by MDP or Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection involves the stable polyubiquitination of Rip2. J Biol Chem 282: 36223–36229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou A, Tenev T, Goyal L, Agapite J, Steller H, Meier P 2003. IAP-antagonists exhibit non-redundant modes of action through differential DIAP1 binding. EMBO J 22: 6642–6652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarnegar BJ, Wang Y, Mahoney DJ, Dempsey PW, Cheung HH, He J, Shiba T, Yang X, Yeh WC, Mak TW, et al. 2008. Noncanonical NF-κB activation requires coordinated assembly of a regulatory complex of the adaptors cIAP1, cIAP2, TRAF2 and TRAF3 and the kinase NIK. Nat Immunol 9: 1371–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhou X, McQuade T, Li J, Chan FK, Zhang J 2011. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature 471: 373–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Silverman N, Hong M, Liao DS, Chung Y, Chen ZJ, Maniatis T 2005. The role of ubiquitination in Drosophila innate immunity. J Biol Chem 280: 34048–34055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang ZH, Sun L, Kong L, Hu JH, Yu MC, Reinach P, Zang JW, Ge BX 2006. Drosophila TAB2 is required for the immune activation of JNK and NF-κB. Cell Signal 18: 964–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann KC, Ricci JE, Droin NM, Green DR 2002. The role of ARK in stress-induced apoptosis in Drosophila cells. J Cell Biol 156: 1077–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]