Abstract

Emphasis has been placed in this article dedicated to DNA damage on recent aspects of the formation and measurement of oxidatively generated damage in cellular DNA in order to provide a comprehensive and updated survey. This includes single pyrimidine and purine base lesions, intrastrand cross-links, purine 5′,8-cyclonucleosides, DNA–protein adducts and interstrand cross-links formed by the reactions of either the nucleobases or the 2-deoxyribose moiety with the hydroxyl radical, one-electron oxidants, singlet oxygen, and hypochlorous acid. In addition, recent information concerning the mechanisms of formation, individual measurement, and repair-rate assessment of bipyrimidine photoproducts in isolated cells and human skin upon exposure to UVB radiation, UVA photons, or solar simulated light is critically reviewed.

Culprits of cellular DNA damage include oxidizing agents (e.g., hydroxyl radicals, which generate numerous pyrimidine and purine base lesions) and UV radiation (e.g., UVA, which produces pyrimidine dimers).

In this article, we emphasize recent developments in the formation of damage to cellular DNA mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidizing agents, including singlet oxygen, the hydroxyl radical (•OH), one-electron oxidants, hypochlorous acid (HOCl), and ten-eleven translocation (TET) oxygenases involved in epigenetic regulation. These advances have been possible because of the development of sensitive and powerful high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS)/mass spectrometry (MS) methods allowing one to revise previously reported data obtained using methods such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), immunoassays, and HPLC with single MS detection (Cadet et al. 2011, 2012a). Considerable progress has also been made in the elucidation of oxidative degradation pathways of isolated DNA and related model compounds (for recent comprehensive reviews, see Gimisis and Cismaş 2006; Neeley and Essigmann 2006; Pratviel and Meunier 2006; von Sonntag 2006; Cadet et al. 2008, 2010, 2012b; Dedon 2008; Burrows 2009; Wagner and Cadet 2010). In addition, there is much complementary information on solar-radiation-induced formation of bipyrimidine photoproducts in the DNA of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and human skin. In particular, the distribution of UVA and UVB photoproducts has been determined, allowing accurate determination of their rates of repair (Cadet et al. 2009, 2012c).

OXIDATIVELY GENERATED DAMAGE TO DNA

About 100 oxidatively generated base lesions and 2-deoxyribose modifications, including initially formed thymidine hydroperoxides and diastereomeric nucleosides, have been isolated and identified in model studies (Cadet et al. 2010, 2012b). The number of products detected in cellular DNA is much lower, owing to several limitations and difficulties. These include, among others, the lack of sensitivity of available methods for detecting lesions produced in low yields, instability of some modifications such as base hydroperoxides, optimization of assays that may require the synthesis of internal standards labeled with stable isotopes, and finally, artefactual oxidation of overwhelming normal nucleosides during DNA extraction and subsequent workup (Cadet et al. 2011, 2012a).

Single Lesions

Hydroxyl Radical

The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is a highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) that efficiently reacts with nearby biomolecules at diffusion-controlled rates of reaction. The reaction volume of •OH is less than 2 nm in cells and tissues; thus, it reacts essentially at the site of generation. The most likely source of •OH in cells is the Fenton reaction (Winterbourn 2008), which involves the reaction of reduced redox active metal ions, such as ferrous and cuprous ions, with metabolically produced H2O2. For this reason, the main lines of defense against ROS by aerobic organisms include metal-binding chelators and proteins (e.g., ferritin) to minimize the concentration of labile metal ions, together with catalase and peroxidases to minimize the concentration of H2O2. The generation of •OH by Fenton-like reactions is believed to take place in a site-specific manner, for example, involving metal ions in close proximity or bound to DNA. •OH is also generated by the radiolysis of water molecules according to the so-called indirect effect of ionizing radiation (von Sonntag 2006).

Thymine

Two main reactions mediated by •OH have been shown to take place with thymine nucleobases in cellular DNA: addition across the 5,6-pyrimidine bond and H-atom abstraction from the methyl group (Fig. 1). Model studies have shown that •OH preferentially adds to C5 and to a lesser extent to C6, giving rise to reducing C6-yl and oxidizing C5-yl radicals, respectively (von Sonntag 2006). In the case of nucleoside thymidine, O2 rapidly adds to the radical site, giving rise to the corresponding hydroperoxyl radicals that subsequently convert into eight cis and trans diastereomers of 5-hydroxy-6-hydroperoxy-5,6-dihydrothymidine and 6-hydroxy-5-hydroperoxy-5,6-dihydrothymidine (Wagner et al. 1994). The major radiation-induced base degradation products so far detected in cellular DNA are the cis and trans diastereomers of 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymine (Thy-Gly; see base modifications in Fig. 1) (Pouget et al. 2002; Douki et al. 2006). These products may be explained by stereospecific reduction of intermediate thymine hydroperoxides. Thymine hydroperoxides may also decompose by pyrimidine ring cleavage to 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin derivatives (Hyd-Thy), which was recently detected in irradiated cells (Samson-Thibault et al. 2012). The second major pathway of •OH-mediated decomposition of thymine and its derivatives, including DNA in solution, involves H-atom abstraction from the methyl group. This leads to the 5-(uracilyl)methyl radical, which is readily converted into the corresponding peroxyl radical after O2 addition and hydroperoxide after subsequent reduction and protonation (Wagner et al. 1994). In turn, hydroperoxide decomposes by reduction and competitive dehydration to 5-hydroxymethyluracil (5-HmUra) and 5-formyluracil (5-FoUra) derivatives, respectively. The latter products are major oxidation products detected in cellular DNA by HPLC coupled to electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) (Pouget et al. 2002; Douki et al. 2006). The 5-(uracilyl)methyl radical can also react with neighboring guanine and adenine bases to produce intrastrand or possibly interstrand cross-links connected between the methyl group of thymine and the C8 position of either guanine (G[8-5 m]T) or adenine (DNA intrastrand cross-links; Fig. 1). The latter products have been observed in both isolated and cellular DNA exposed to γ rays (Bellon et al. 2006; Jiang et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

Oxidation of thymine (Thy). Radicals are shown in red and diagmagnetic intermediates in blue. Only the base moiety is shown. In the case of 2′-deoxyribonucleosides, the base is attached to a 2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranose moiety. C5,C6-OH adducts include 5-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymin-6-yl and 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymine-5-yl radicals. 5,6-OH,OOH include thymine hydroperoxides: 5-hydroxy-6-hydroperoxy- and 6-hydroxy-5-hydroperoxy-5,6-dihydrothymine. Deprotonation of thymine radical cations gives 5-(uracilyl)methyl radicals and 5-hydroperoxylmethyluracil as the main initial products. Oxidation of the 5,6-double bond gives 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymine (thymine 5,6-glycols, Thy-Gly) and 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin (Hyd-Thy). Oxidation of the methyl group gives 5-hydroxymethyluracil (5-HmUra) and 5-formyluracil (5-FoUra). The 5-(uracilyl)-methyl radical may also react with neighboring guanine or adenine to give intrastrand cross-links, for example, G[8-5 m]T. The above products have been detected in cellular DNA.

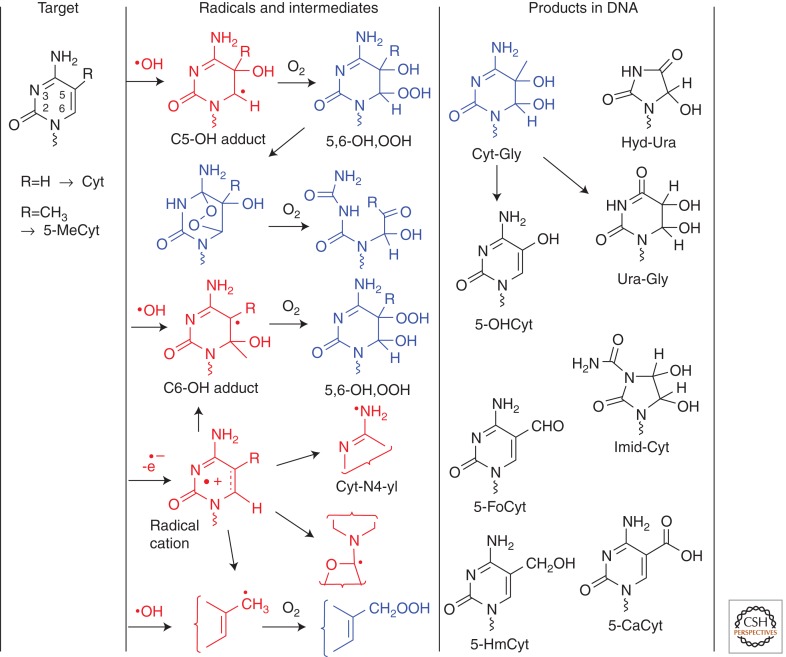

Cytosine and 5-Methylcytosine

There has been considerable progress in the analysis of cytosine and 5-methylcytosine oxidation products. Similar to the •OH-mediated decomposition of thymine, the initial mechanism of decomposition of cytosine derivatives involves •OH adducts, peroxyl radicals, and hydroperoxides (Fig. 2). From the mixture of •OH-induced decomposition of the nucleoside 2′-deoxycytidine, more than 30 products, including diastereomers, have been isolated and characterized by MS and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Wagner et al. 1999; Wagner and Cadet 2010). Several stable products of cytosine have been detected in cellular DNA (Wagner et al. 1992; Lenton et al. 1999; Rivière et al. 2006; Samson-Thibault et al. 2012). In contrast to the hydroperoxides of thymine, the hydroperoxides of cytosine rapidly decompose to intermediate compounds (uracil hydroperoxides and a cyclic endoperoxide). The latter products account for the formation of labile products such as cytosine glycol (Cyt-Gly) and stable products: 5-hydroxycytosine (5-OHCyt), 5-hydroxyuracil (5-OHUra), 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6- dihydrouracil (Ura-Gly), 5-hydroxyhydantoin (Hyd-Ura), and 1-carbamoyl-4,5-dihydroxy-2-oxoimidazolidine (Imid-Cyt) (see base modifications in Fig. 2). Of particular interest, Cyt-Gly appears to undergo competitive dehydration to 5-OHCyt (90%–70%) and deamination to Ura-Gly (10%–30%) in double-stranded DNA (Tremblay et al. 1999; Tremblay and Wagner 2008). Other intermediates include uracil hydroperoxides, which again have not been characterized because of their rapid decomposition but likely account for the formation of some common oxidation products: Ura-Gly, 5-OHUra, and Hyd-Ura. There is strong evidence for the formation of a cyclic intermediate endoperoxide of cytosine that accounts for the formation of Imid-Cyt. Although Imid-Cyt isomers are major oxidation products of cytosine derivatives, the yield appears to be greatly reduced in isolated and cellular DNA compared to the monomers in solution. The oxidation products of cytosine are unstable because they are highly susceptible to deamination upon saturation of the 5,6-double bond, leading to products that are analogues of uracil. In addition, some oxidation products of cytosine nucleoside are prone to autooxidation (5-OHCyt and 5-OHUra) (Rivière et al. 2004, 2005) or isomerization into a complex mixture of products (Hyd-Ura and Imid-Cyt) (Rivière et al. 2005; Tremblay et al. 2007). •OH-induced oxidation of 5-methylcytosine is very similar to that of cytosine, with respect to oxidation of the nucleoside in aerated aqueous solutions. The initial addition of •OH and O2 to the 5,6-double bond of 5-methylcytosine leads to the formation of intermediate hydroperoxyl radicals and 5(6)-hydroperoxides, which decompose to 5-methylcytosine 5,6-glycol, 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin, and 1-carbamoyl-4,5-dihydroxy-5-methyl- 2-oxoimidazolidine derivatives. In contrast to the 5,6-glycols of 2′-deoxycytidine, the corresponding 5,6-glycols of 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine are about 30-fold more stable toward deamination in aqueous neutral solution (Cao et al. 2009). Lastly, H-atom abstraction from the methyl group of 5-methylcytosine produces 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-formylcytosine, similar to the case of thymine oxidation. There is a lack of information concerning the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine induced by ionizing radiation or Fenton reactions in isolated and cellular DNA.

Figure 2.

Oxidation of cytosine (Cyt). C5,C6-OH adducts include 5-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosin-6-yl and 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosin-5-yl radicals. 5,6-OH,OOH include cytosine hydroperoxides: 5-hydroxy-6-hydroperoxy-5,6-dihydrocytosine and 6-hydroxy-5-hydroperoxy-5,6-dihydrocytosine. The deprotonation of cytosine radical cations gives C6-OH adducts, cytosin-N4-yl (Cyt-N4-yl) radicals, and 2′-deoxycytidin-C1′-yl radicals; in addition, 5-(cytosinyl)methyl radicals are generated in the case of 5-methylcytosine. Initial cytosine 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosine (cytosine 5,6-glycols, Cyt-Gly) decomposes to 5-hydroxycytosine (5-OHCyt) and 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydrouracil (uracil 5,6-glycols, Ura-Gly). Other products of the 5,6-double bond of cytosine include 5-hydroxyhydantoin (Hyd-Ura) and 1-carbamoyl-3,4-dihydroxy-2-oxoimidazolidine (Imid-Cyt). Radical-mediated or enzymatic oxidation of the methyl group of 5-methylcytosine gives 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-HmCyt), 5-formylcytosine (5-FoCyt), and 5-carboxycytosine (5-CaCyt). The above products have been detected in cellular DNA except for Cyt-Gly.

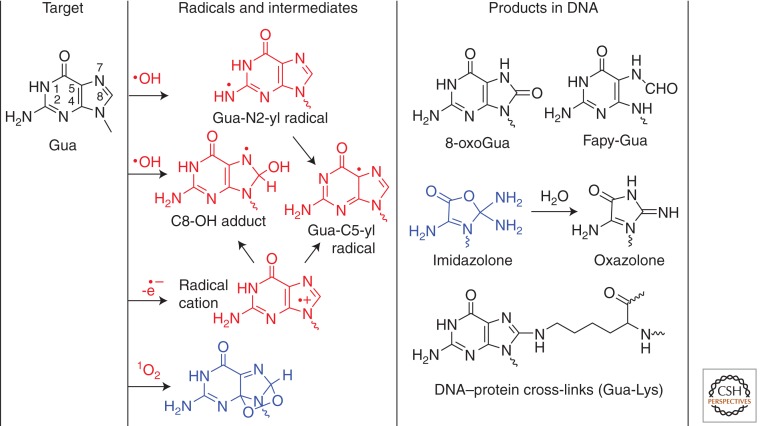

Guanine

Two main degradation products of guanine, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoGua) and 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy-Gua), increase in the DNA of human monocytes exposed to γ rays and heavy particles as measured by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS (Pouget et al. 2002; Douki et al. 2006). The formation of these products is likely partly explained by initial •OH addition to C8 of the guanine base generating 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroguan-8-yl radicals (Fig. 3). In addition, there is compelling evidence to suggest the participation of vicinal pyrimidine peroxyl radicals in the formation of both 8-oxoGua and Fapy-Gua (Douki et al. 2002a; Bergeron et al. 2010). The fate of 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroguan-8-yl radicals is dependent on the redox environment such that the radical undergoes competitive one-electron oxidation (i.e., in the presence of O2) to give 8-oxoGua, as well as one reduction to lead to opening of the imidazole ring with subsequent generation of Fapy-Gua (Cadet et al. 2008, 2010). It is worth noting that Fapy-Gua is produced with a higher efficiency than 8-oxoGua in cellular DNA (Pouget et al. 2002), in contrast to what is observed in free DNA (Frelon et al. 2000). This may be accounted for by the lower oxygen concentration and the presence of reducing compounds such as thiols in the cellular environments. The formation of 2,2,4-triamino-5(2H)-oxazolone (oxazolone), a well-documented •OH and one-electron oxidation product of Gua nucleoside (Cadet et al. 1994), has been detected in the hepatic DNA of diabetic rats, albeit the yield was tenfold lower than that of 8-oxoGua (Matter et al. 2006). The formation of oxazolone is rationalized in terms of initial •OH-mediated H-atom abstraction from the 2-amino group of guanine (Chatgilialoglu et al. 2011a) as a more relevant alternative to •OH addition at C4 followed by dehydration, which was initially proposed several years ago (Candeias and Steenken 2000). The resulting N-centered radical rearranges to the G(-H)• guanyl radical, which is also generated by deprotonation of the guanine radical cation produced by one-electron oxidation. The formation of oxazolone from G(-H)• guanyl radicals involves a series of complex reactions followed by slow hydrolysis of 2-amino-5-4H-imidazol-4-one. These include addition of the superoxide radical anion (O2•–) at C5 followed by nucleophilic addition of H2O, opening of the pyrimidine ring, release of formamide, and rearrangement (Cadet et al. 1994, 2008; Misiaszek et al. 2004). Hydrolysis of the nucleoside imidazolone derivative, whose half-life in aqueous solution has been shown to be close to 10 h at 20°C at neutral pH, leads quantitatively to oxazolone (Gasparutto et al. 1998).

Figure 3.

Oxidation of guanine (Gua). The reaction of •OH gives 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroguan-8-yl radicals (C8-OH adduct) and guanine-N2-yl radicals (Gua-N2-yl), which transform into guanine-C5-yl radicals (G(-H•) guanyl radical, Gua-C5-yl). The guanine radical cation undergoes competitive hydration to the C8-OH adduct and deprotonation to Gua-C5-yl. The main products include 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoGua), 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy-Gua), and 2-amino-5-4H-imidazol-4-one (imidazolone), which transforms to 2,2,4-triamino-5(2H)-oxazolone (oxazolone). The radical cation of guanine may undergo addition with lysine to form DNA–protein cross-links (Gua-Lys). The reaction of single oxygen (1O2) leads to the formation of an intermediate 4,8-endoperoxide, which decomposes mainly to 8-oxoGua. The above products have been detected in cellular DNA, except for imidazolone and Gua-Lys cross-links.

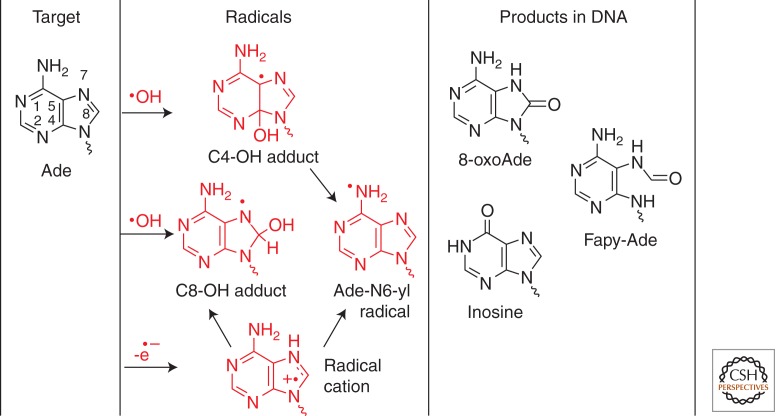

Adenine

The oxidation of adenine is similar to that of guanine, leading to 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroadenine (8-oxoAde) and 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy-Ade) as the main products. These products have been measured as modified nucleosides by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in the DNA of human monocytes following exposure to γ rays and high LET heavy ions (Pouget et al. 2002). Similarly, the formation of 8-oxoAde and Fapy-Ade is accounted for by initial •OH addition at C8 (as the common step) followed by either one-electron oxidation or reduction of the adenine N7-yl radical thus formed, respectively (Fig. 4) (Cadet et al. 2008, 2010). Initially, the formation of 2-hydroxyadenine upon addition of •OH to the C2 position of adenine was proposed on the basis of GC-MS measurements in cellular DNA (Mori and Dizdaroglu 1994), but it was later ruled out from the lack of HPLC-MS/MS detection in the DNA of γ-irradiated monocytes (Frelon et al. 2002). One should note that the yield of 8-oxoAde and Fapy-Ade are about eight- to tenfold lower than the corresponding yields of 8-oxoGua and Fapy-Gua. Such a disparity in yields may be explained in part by the low oxidation potential of guanine, which can result in the transfer of an electron from guanine radicals in close proximity (Bergeron et al. 2010). This can lead to the formation of tandem or clustered lesions involving guanine, and in general, direct more damage toward guanine via guanine radical cations. In addition, the disparity between guanine and adenine oxidation in DNA may be explained by the lack of formation of adenine oxidation products. About 50% of the initial reactions of •OH occur at C4 of adenine (Vieira and Steenken 1990), leading to an adduct radical that rapidly undergoes dehydration to Ade-N6-yl radicals. This radical has recently been characterized in isolated DNA treated with Cu2+/H2O2 by electron paramagnetic resonance DMPO radical adducts and MS analysis of stable nitrone products (Bhattacharjee et al. 2011, 2012). The chemistry of Ade-N6-yl radicals in DNA is not well understood. As a model system, the near-UV photolysis of the N6-phenylhydrazone of adenine nucleoside was shown to generate strongly oxidizing Ade-N6-yl radicals in aqueous solution. On the basis of product analysis, the major reaction of Ade-N6-yl radicals involves electron or H-atom abstraction giving back adenine (major reaction), and to a lesser extent, the radicals undergo deamination to inosine and radical addition with DNA bases giving dimeric compounds (Kuttappan-Nair et al. 2010). Thus, the low yield of adenine oxidation products may be explained by the regeneration of adenine. In view of the strong oxidizing properties of Ade-N6-yl radicals, it is also reasonable that the aden-N6-yl radical undergoes electron transfer in DNA, thereby transferring initial damage from adenine to guanine.

Figure 4.

Oxidation of adenine (Ade). The reaction of •OH gives 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroaden-8-yl radicals (C8-OH adduct) and 4,5-dihydroaden-C5-yl radicals (C4-OH adduct), which transform into adenin-N6-yl radicals (Ade-N6-yl). The adenine radical cation undergoes competitive hydration to the C8-OH adduct and deprotonation to Ade-N6-yl radicals. The main products include 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroadenine (8-oxoAde) and 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy-Ade). Inosine may also form by deamination of intermediate adenine radical cations. The above products have been detected in cellular DNA.

One-Electron Oxidants

Several biologically relevant systems are available for inducing one-electron reactions of nucleobases whose one-electron ionization potentials decrease in the following order: guanine < adenine < cytosine ∼ thymine. Ionizing radiation and high-intensity 266-ns laser photolysis are able to ionize all of the five main DNA bases with similar efficiency, whereas most type I photosensitizers including 6-thioguanine mainly target guanine. One-electron oxidation of nuclear guanine may also be achieved with either potassium bromate once metabolized (Kawanishi and Murata 2006) or carbonate anion (Lee et al. 2007), the decomposition product of nitrosoperoxycarbonate that is generated in the reaction of peroxynitrite with CO2/bicarbonate (Medinas et al. 2007). Comprehensive mechanisms have been proposed from the chemical reactions of the pyrimidine and purine radical cations that involve deprotonation and/or hydration in the initial step of oxidation (Figs. 1–4). Two-quantum UVC laser-mediated ionization of nucleobases in cellular DNA was investigated with the aim of specifically mimicking the direct effects of ionizing in the absence of any contribution of •OH (Douki et al. 2004). The main one-electron oxidation product formed in cellular DNA upon exposure of THP1 neoplastic human monocytes to high-intensity 266-ns laser pulses was 8-oxoGua, as inferred from enzymatic digestion of DNA and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of the modified nucleosides (Douki et al. 2006). The formation of 8-oxoGua involves the transient generation of 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroguanyl radicals as the result of initial hydration of guanine radical cations followed by one-electron radical oxidation (Fig. 3). In addition, six oxidation products of thymidine were detected, including the 2′-deoxyribonucleoside derivatives of 5-HmUra, 5-FoUra, and the four cis and trans diastereomers of Thy-Gly (Douki et al. 2006). These products can be explained by competitive hydration and deprotonation of transient thymine radical cation. The hydration of thymine radical cation specifically takes place at C6, giving oxidizing 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymin-5-yl radicals, the precursors of Thy-Gly through the transient generation of 6-hydroxy-5-hydroperoxy-5,6-dihydrothymine (Fig. 1). In contrast, competitive deprotonation of the thymine radical cation exclusively occurs from the exocyclic methyl group giving rise to the 5-(uracilyl) methyl radical and subsequently to 5-HmUra and 5-FoUra through the intermediary of the corresponding hydroperoxide (Wagner et al. 1994; Cadet et al. 2012b). The yield of 8-oxoGua is about sixfold higher than that of the combined levels of thymine oxidation products. This result strongly indicates the efficient transfer of purine and pyrimidine radical cations to guanine as the preferential trapping site. The ability to transfer base radical cations in DNA depends on the oxidation potential of the base, the nature of the bridge separating initial and final radical cations, and finally, the chemical environment of DNA.

Singlet Oxygen

Singlet oxygen (1O2), a major contributor of the UVA radiation-mediated oxidation reactions to cellular DNA through a type II photosensitization mechanism (Cadet et al. 2008, 2009), reacts selectively with guanine components at the exclusion of other nucleobases and the 2-deoxyribose moiety (Ravanat et al. 2001). In the latter case, this is consistent with the inability of 1O2 to induce DNA strand breaks in cells in significant amounts (Ravanat et al. 2004). The first step in the reaction of 1O2 with the guanine moiety involves Diels-Alder cycloaddition across the 4,8-bond of guanine (Ravanat et al. 2000). In the case of DNA, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodGuo) is exclusively formed through the transient formation of diastereomeric 4,8-endoperoxides (Sheu and Foote 1993) and subsequent rearrangement into linear 8-hydroperoxy-2′-deoxyguanosine followed by its reduction into 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine. The enol tautomer 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine is in dynamic equilibrium with the 6,8-diketo form 8-oxodGuo. However, UV and NMR spectroscopic measurements (Culp et al. 1989; Cho et al. 1990; Kouchakdjian et al. 1991; Oda et al. 1991) together with theoretical calculations (Aida and Nishimura 1987; Venkatatesmarlu and Leszczynski 1998) indicate that the 6,8-diketo (i.e., 8-oxodGuo) is the predominant form in solution. For this reason, we prefer using the name for the nucleobase (8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine, 8-oxoGua) or for the nucleoside (8-oxodGuo) for describing this ubiquitous DNA oxidation product (Cooke et al. 2010; Cadet et al. 2012d). However, Kasai and Nishimura, who discovered the base lesion in 1983 (Kasai and Nishimura 1983) retain the term of 8-hydroxyguanine (Nishimura 2011). This product is recognized as the main DNA biomarker of oxidative stress that is usually measured in cellular DNA (Cadet et al. 2011) and biological fluids (Cooke et al. 2008) by HPLC coupled with either electrochemical detection (ECD) or ESI-MS/MS. This oxidized base may also be detected, however less specifically, using DNA repair enzymes, including bacterial formamidopyrimidine, DNA glycosylase, and 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase, in association with either the alkaline comet assay (Azqueta et al. 2009) or the alkaline elution technique (Trapp et al. 2007) for revealing the presence of enzymatically generated DNA strand breaks.

Hypochlorous Acid

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is generated in neutrophils during inflammation upon activation of myeloperoxidase, which triggers the reaction of chloride anion with H2O2 as one of the main cellular systems for eradicating microorganisms (Malle et al. 2007). HOCl and hypochlorite (OCl–), its conjugate base, have been shown to efficiently chlorinate cellular DNA and RNA nucleobases (Masuda et al. 2001; Badouard et al. 2005). The main modified nucleobases were found to be 5-chlorocytosine (5-ClCyt), 8-chloroadenine (8-ClAde), and 8-chloroguanine (8-ClGua) in the DNA and RNA of SKM-1 cells incubated with HOCl on the basis of HPLC-ESI/MS/MS measurements (Badouard et al. 2005). 5-ClCyt appears to be a relevant indicator of inflammation because the level of the halogenated pyrimidine increases in the DNA of diabetic patients in comparison to that of healthy control volunteers (Asahi et al. 2010). HOCl can also react with DNA bases to generate the corresponding chloramine, which subsequently decomposes to aminyl radicals. The major radical adducts from a mixture of nucleosides are N-centered radicals at the exocyclic amino positions of cytosine and adenine (Hawkins and Davies 2001, 2002).

Enzymatic Oxidation of 5-Methylcytosine by Ten-Eleven Translocation Proteins (Epigenetic Modifications)

Two oxidation products of 5-methylcytosine (Fig. 2), 5-hydroxymethycytosine (5-HmCyt) and 5-formylcytosine (5-FoCyt), previously characterized in model studies involving one-electron oxidant of the nucleoside (Bienvenu et al. 1996), were found to be generated enzymatically and play a role in epigenetics (Kriaucionis and Heintz 2009; Tahiliani et al. 2009; Iqbal et al. 2011; Münzel et al. 2011; Pfaffeneder et al. 2011). More recently, 5-carboxycytosine (5-CaCyt) was characterized as the ultimate enzymatic oxidation product of 5-methylcytosine (Ito et al. 2011; Pfaffeneder et al. 2011; Wu and Zhang 2011; Zhang et al. 2012). 5-Methylcytosine and its oxidation products are measured using HPLC coupled to MS using isotopically labeled standards (Jin et al. 2011; Kraus et al. 2012). Depending on the cell line or tissue, 5-HmCyt reaches levels of 0.7%/Cyt, whereas the levels of 5-FoCyt and CaCyt are estimated to be tenfold lower (Münzel et al. 2010; Pfaffeneder et al. 2011). The levels of enzymatically generated 5-methylcytosine oxidation products are two to three orders of magnitude higher than that of oxidatively generated damage in DNA.

Tandem Base Lesions (•OH and One-Electron Oxidation)

Tandem base modifications may be generated by single radical species arising from initial •OH or one-electron oxidation reactions. In general, the efficiency of an intramolecular reaction is higher when the target base is located on the 5′ side with respect to the attacking pyrimidine radical, as the result of shorter distances between the radical and target molecule.

Lesions Formed Mainly in the Absence of O2

Tandem base lesions resulting from intramolecular addition of either 5-(uracilyl)methyl radicals or 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosin-5-yl radicals to 5′-adjacent guanine moieties are generated in the DNA of cells exposed to H2O2 (In et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2007). These products were quantified by high-sensitivity HPLC-ESI/MS3 that can detect a very low frequency of lesions on the order of a few lesions per 109 normal nucleosides for a sample injection of 30–50 µg. The presence of O2, which efficiently reacts with C-centered radicals, including the above radicals, greatly limits the formation of the G[8-5 m]T and G[8-5]C lesions.

Lesions Formed in the Presence of O2

The first evidence for implication of •OH in the formation of tandem base modifications in aerated aqueous solutions came from the pioneering work of Box and his collaborators (Box et al. 1993). More recently, it was shown that pyrimidine peroxyl radicals formed by oxidative reactions involving either •OH or one-electron oxidants are able to efficiently add to adjacent purine (Douki et al. 2002a) and pyrimidine bases (In et al. 2007), giving rise to tandem base lesions in isolated DNA (Bourdat et al. 2000). For example, the addition of •OH and then O2 to thymine can generate a hydroperoxyl radical (preferentially at C6) that subsequently reacts with guanine (C8), leading to the formation of tandem formamide and 8-oxoGua lesions (Douki et al. 2002a). However, none of the above tandem base lesions has been detected in cellular DNA, probably because of a lack of sensitivity of the currently available analytical methods. However, the formation of tandem lesions was recently supported by labeling experiments showing that a large percentage (50%) of 8-oxoGua and 8-oxoAde are labeled by 18O2 rather than H2 18O when DNA is irradiated in aqueous solution (Bergeron et al. 2010). Another example of tandem lesions via a single radical involves the formation of a guanine-thymine cross-link upon initial formation of guanine radical cation, which has thus far only been observed in isolated DNA (Yun et al. 2011; Ding et al. 2012).

DNA–Protein Cross-Links (One-Electron Oxidation)

Following an early observation that guanine radical cations are susceptible to nucleophilic addition with H2O, the central lysine residue of KKK peptide was shown to react with guanine radical cations in bound TGT trinucleotides, giving rise to a lysine-guanine cross-link between ε-amino group and the C8 position of guanine (Perrier et al. 2006) (see DNA–protein cross-links; Fig. 3). This system provides a relevant model to study the formation of radiation-induced DNA–protein cross-links in cells. In this respect, one may quote recent investigations dealing with the UVA irradiation of 6-thioguanine-containing DNA, which was found to lead to the formation of DNA–protein cross-links in human cells (Brem et al. 2011; Gueranger et al. 2011; Brem and Karran 2012). According to the high efficiency for photoexcited 6-thioguanine to intramolecularly oxidize guanine by one-electron, one may anticipate that the observed formation of DNA–protein cross-links takes place by nucleophilic addition of proteins bearing a free amino group to guanine radicals.

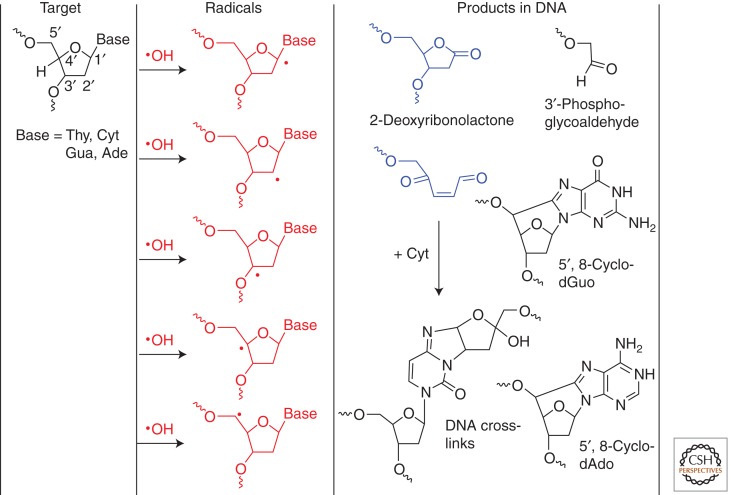

Purine 5′,8-Cyclonucleosides

The mechanism of formation of purine 5′,8- cyclonucleosides is now well documented (Belmadoui et al. 2010; Chatgilialoglu et al. 2011b). The pathway is initiated by •OH-mediated H-atom abstraction from the exocyclic 5′-hydroxymethyl group, followed by efficient intramolecular cyclization, giving rise to intrastrand base-sugar cross-links (Fig. 5). It was also shown that the efficiency of formation for both 5′R and 5′S diastereomers of 5′,8-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine (5′,8-cyclodAdo) and 5′,8-cyclo-2′-deoxyguanosine (5′,8-cyclodGuo) in DNA is strongly dependent on the concentration of O2 because it reacts in a competitive way with C-centered 5-yl sugar radicals that are precursors of the above products (Belmadoui et al. 2010). This explains why only traces of the (5′R) diastereomer of 5′,8-cyclodAdo were detected in human cells exposed to 2000 Gy by HPLC-MS/MS with a measured yield of two orders of magnitude lower than that of 8-oxoGua (Belmadoui et al. 2010). In contrast, higher levels of purine 5′,8-cyclonucleosides have been reported using HPLC-MS and GC-MS methods, probably because of the presence of interfering peaks (D’Errico et al. 2006, 2007). The background levels of both 5′R and 5′S diastereomers of 5′,8-cyclodAdo and 5′,8-cyclodGuo were recently measured by HPLC-MS3 in several tissues of healthy rats to be between 1.5 and 1.8 lesions per 107 nucleosides in the liver of 3-mo-old rats (Wang et al. 2011). In comparison, the levels of (5′R) and (5′S) diastereomers of 5′,8-cyclodAdo in mouse liver DNA were 0.13 and 0.48 lesions per 107 nucleosides by HPLC-MS/MS (Jaruga et al. 2009). The accumulation of purine 5′,8-cyclo-2′-deoxyribonucleosides appears to increase in genomic DNA of wild-type mice and ERCC1-deficient mice with age in a tissue-specific manner, with liver being the most sensitive target (Wang et al. 2012). Levels of the 5′R diastereomer of 5′,8-cyclodAdo were found to be higher than 80 lesions per 107 nucleosides in liver DNA of 21-wk-old progeroid Ercc-/Δ mice that suffer from DNA nucleotide excision repair deficiency. This is somewhat surprising considering that a dose of 2000 Gy of γ rays generates only 0.2 of the 5′R diastereomer of 5′,8-cyclodAdo per 109 nucleosides (Belmadoui et al. 2010).

Figure 5.

Oxidation of the 2-deoxyribose moiety. The reaction of OH results in the abstraction of hydrogen atoms from the 2-deoxyribose, giving five C-centered radicals. These radicals explain the formation of various oxidation products: abstraction at C1′ gives 2-deoxyribonolactone; abstraction at C5′ gives 3′-phosphoglycoaldehyde, and abstraction at C4′ gives an intermediate unsaturated dialdehyde that can couple with cytosine to form a DNA inter- or intrastrand cross-link. In addition, the C5′-centered radicals of 2-deoxyribose can react with the corresponding base moiety to produce 5′,8-cyclo-2′-deoxyguanosine (5′,8-cyclo-dGuo) and 5′,8-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine (5′,8-cyclo-dAdo). The above products have been detected in cellular DNA, except for the dialdehyde intermediate.

DNA Interstrand Cross-Links

Two main oxidative pathways have been identified so far in which interstrand cross-links (ICLs) are produced between two opposite DNA strands.

Cross-Links Involving C4′–Oxidized Abasic Sites

The mechanism of formation of ICLs involving initial •OH-mediated H-atom abstraction from the C4 of the 2-deoxyribose has been studied in certain detail (Regulus et al. 2004, 2007; Sczepanski et al. 2011). From the site-specific generation of C4 sugar radicals using a photolabile precursor, the formation of ICLs is favored by the presence of adenine on complementary DNA strands containing adenine and, to a lesser extent, cytosine (Fig. 5). Both nucleophilic bases promote beta-elimination from the acyclic form of C4 oxidized abasic sites (Sczepanski et al. 2009, 2011). The highly reactive unsaturated ketone thus generated is now able to efficiently react with opposite cytosine or adenine residues. One may point out that the only products detected in cellular DNA upon either exposure to γ rays or incubation with radiomimetic bleomycin are the adducts of 2′-deoxycytidine, which consist of four diastereomers of 6-(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-2-hydroxy-3(3-hydroxy-2-oxopropyl)-2,6-dihydroimidazo[1,2-c]-pyrimidin-5(3H)-one (Regulus et al. 2007).

Cross-Links Involving Nucleophilic Addition to Guanine Radical Cations

As discussed in previous sections, it is now well documented that guanine radical cations readily undergo nucleophilic addition with H2O and the free ε-amino group of lysine. As a further extension, one-electron oxidation of guanine bases located in the center of DNA duplexes leads to the efficient formation of DNA ICLs that may be rationalized by intramolecular addition of (likely) cytosine on the opposite strand (Cadet et al. 2012e). However, the exact mechanism of crosslinking awaits further experiments (D Angelov, H Menoni, J-L Ravanat, et al., unpubl.). A similar mechanism may account for the formation of DNA ICLs upon UVA irradiation of cells preincubated with 6-thiopurine (Brem et al. 2011).

PHOTO-INDUCED DAMAGE TO CELLULAR DNA

Recent achievements in the measurement and repair of direct and photosensitized DNA damage induced by UVB and UVA components of solar radiation in isolated cells and human skin have been accomplished through the advent of analytical techniques such as HPLC-ESI-MS/MS (Douki et al. 2000; Douki and Cadet 2001). In addition, major mechanistic insights have been gained in the UVA-mediated formation of cis-syn cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and the Dewar valence isomers (DEWs), the third class of bipyrimidine DNA photoproducts.

Formation and Repair of UVB-Induced DNA Photoproducts

Application of HPLC-ESI-MS/MS allows one to determine the distribution of 12 possible bipyrimidine photoproducts, including the three classes of dimeric lesions, namely CPDs, pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidone photoproducts (6-4PPs), and the corresponding Dewar valence isomers (DEWs) at TT, TC, CT, and CC sites. Strikingly, there is a similar distribution of UVB- induced bipyrimidine photoproducts that was observed in isolated DNA, fibroblasts, kertinocytes (Douki and Cadet 2001; Douki et al. 2001, 2003; Courdavault et al. 2004, 2005) as well as in explants of human skin. Thymine cyclobutane dimer (T <> T) is the predominant photoproduct, followed in decreasing order of importance by T <>C > 6-4TC > C <>T > C <>C > 6-4 TT with trace amounts of the two other 6-4PPs (Mouret et al. 2006). It should be noted that under UVB-irradiation, the formation of DEWs was not observed in cells, with the exception of very small amounts at CC sites. In addition, 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosine, the so-called cytosine photohydrate, was barely detectable in the DNA of UVC-irradiated cells (Douki et al. 2002b). It was also shown that 8-oxoGua and single-strand breaks are generated with a very low efficiency that is about two to three orders of magnitude lower than that of bipyrimidine photoproducts in cells exposed to UVB radiation (Kielbassa et al. 1997; Douki et al. 1999; Cadet et al. 2012c). It remains to be assessed whether adenine-containing interstrand cross-links that have been characterized in model studies (Wang et al. 2001; Davies et al. 2007; Asgatay et al. 2010; Su et al. 2010) are formed in cellular DNA. Increasing interest is being devoted to the photoreactions of 5-methylcytosine at CpG sites because of the implication of methylated cytosine in epigenetic regulation. 5-Methylcytosine is very susceptible to UVB radiation (Pfeifer et al. 2005). However, the product distribution of CPD and 6-4PP of 5-methylcytosine, as well as their quantitative importance, remain to be determined in cellular DNA. HPLC-ESI-MS/MS has also been used to determine the rate of removal of the main UVB-induced CPDs and 6-4PPs by nucleotide excision repair in fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and human skin (Mouret et al. 2006, 2008). The rate of excision of CPDs is dependent on the primary sequence with the following decreasing order: C <>T > C <>C > T <>T <> T. It is worth noting the repair efficiency of C <> C and C <> T is closer to that of 6-4PPs compared to that of T <> T (Mouret et al. 2008).

UVA-Mediated Formation of Cyclobutane Pyrimidine Dimers

Earlier observations showed that UVA radiation is able to induce the formation of CPDs in various cell types (Douki et al. 2003). More recently, HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis indicated that T <> T and, to a lesser extent, T <> C are generated (but not 6-4PP) in fibroblasts, keratinocytes, melanocytes, and human skin (Mouret et al. 2006, 2008, 2011). Histoimmunochemical measurements confirmed the presence of CPDs in the epidermis, whereas 6-4PPs were not detected (Tewari et al. 2012). Interestingly UVB-induced CPDs were predominantly located at the basal level of the epidermis in contrast to CPDs, whose concentration decreases as the depth increases (Tewari et al. 2012). The mechanism of formation of UVA-induced CPDs, which shows features of triple–triplet energy transfer with respect to the distribution of bipyrimidine photoproducts, has remained under debate until recently. The formation of thymine-containing CPDs may be explained by direct UVA photon excitation to novel charge-transfer states, which is favored by base stacking in a DNA duplex and characterized by unique fluorescence properties and the lack of formation of 6-4PP (Mouret et al. 2010; Banyasz et al. 2011). In agreement with this pathway, the formation of CPDs is the predominating type of UVA-mediated DNA damage in both cells and human skin (Cadet and Douki 2011; Halliday and Cadet 2012; Cadet et al. 2012c). Furthermore, the yield of 8-oxoGua produced by 1O2 with a small contribution of •OH is on average fivefold lower than that of CPDs, taking into account the observed variations in cells and skin (Courdavault et al. 2004; Cadet et al. 2009). There is, however, a major exception for melanocytes, in which the yield of CPDs/8-oxoGua is only 1.4 (Mouret et al. 2012). Lastly, it should be noted that oxidized bases and DNA single-strand breaks are produced, albeit in much smaller yields than CPDs, by UVA radiation, whereas there is evidence for the lack of formation of double-strand breaks (Rizzo et al. 2011).

UVA-Induced Isomerization of Pyrimidine (6–4) Pyrimidone Photoproducts

It has been hypothesized for a long time that the formation of DEWs arises from UVB excitation of 6-4PPs and that these products are only formed by exposure to UVC and UVB photons. More recently, evidence was provided showing that photoconversion of 6-4PPs into related DEWs is triggered by UVA radiation, which is poorly absorbed by overwhelming normal DNA bases in comparison to UVB light. This also explains why exposure of cellular DNA to simulated solar radiation gives rise to the formation of DEWs (Douki et al. 2003) through partial isomerization of 6-4PPs (Courdavault et al. 2005) because of efficient 4π electrocyclization (Haiser et al. 2012).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Major achievements have been made in the quantitative and accurate measurement of several oxidatively generated single base lesions in cellular DNA resulting from the exposure to •OH, one-electron oxidants, 1O2• and HOCl. It appears that the levels of base damage are much lower, by about two orders of magnitude, compared to those estimated at the end of the 1990s. It remains to be established what is the biological relevance of most of the single oxidized bases, which in most cases are efficiently removed through base excision repair. It may be added that significant amounts of oxidized purine and pyrimimidine bases are part of tandem base lesions whose characterization and consequences in cells are still pending further investigation. Evidence has been provided for the •OH-mediated formation of intrastrand base cross-links (G[8-5 m]T and G[8-5]C) and purine 5′,8-cyclo-2′-deoxyribonucleosides, which are, however, formed in very low yields. This is also the case for ICLs arising from efficient cycloaddition of reactive aldehydes originating from the C4′ oxidized abasic site opposite and subject to attack by cytosine. There is recent information concerning the formation of DNA proteins and interstrand DNA cross-links caused by the one-electron oxidation of the guanine bases. Efforts should now be made to search for the formation of these two types of complex damage in cellular DNA whose biological role remains to be assessed. It is now possible to propose comprehensive mechanisms of DNA damage arising from ionizing radiation and the damaging effects of solar radiation on DNA in human skin.

Footnotes

Editors: Errol C. Friedberg, Stephen J. Elledge, Alan R. Lehmann, Tomas Lindahl, and Marco Muzi-Falconi

Additional Perspectives on DNA Repair, Mutagenesis, and Other Responses to DNA Damage available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Aida M, Nishimura S 1987. An ab initio molecular orbital study on the characteristics of 8-hydroxyguanine. Mut Res Lett 192: 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi T, Kondo H, Masuda M, Nishino H, Aratani Y, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T, Hisaka S, Kato Y, Osawa T 2010. Chemical and immunochemical detection of 8-halogenated deoxyguanosines at early stage inflammation. J Biol Chem 285: 9282–9291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgatay S, Martinez A, Coantic-Castex S, Harakat D, Philippe C, Douki T, Clivio P 2010. UV-induced TA photoproducts: Formation and hydrolysis in double-stranded DNA. J Am Chem Soc 132: 10260–10261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azqueta A, Shaposhnikov S, Collins AR 2009. DNA oxidation: Investigating its key role in mutagenesis with the comet assay. Mutat Res 674: 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badouard C, Masuda M, Nishino H, Cadet J, Favier A, Ravanat JL 2005. Detection of chlorinated DNA and RNA nucleosides by HPLC coupled to tandem mass spectrometry as potential biomarkers of inflammation. J Chromatogr B 827: 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyasz A, Vayá I, Changenet-Barret P, Gustavsson T, Douki T, Markovitsi D 2011. Base pairing enhances fluorescence and favors cyclobutane dimer formation induced upon absorption of UVA radiation by DNA. J Am Chem Soc 133: 5163–5165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon S, Gasparutto D, Saint-Pierre C, Cadet J 2006. Guanine-thymine intrastrand cross-linked lesion containing oligonucleotides: From chemical synthesis to in vitro enzymatic replication. Org Biomol Chem 4: 3831–3837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmadoui N, Boussicault F, Guerra M, Ravanat JL, Chatgilialoglu C, Cadet J 2010. Radiation-induced formation of purine 5′,8-cyclonucleosides in isolated and cellular DNA: High stereospecificity and modulating effect of oxygen. Org Biomol Chem 8: 3211–3219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron F, Auvré F, Radicella JP, Ravanat JL 2010. HO• radicals induce an unexpected high proportion of tandem base lesions refractory to repair by DNA glycosylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 5528–5533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Deterding LJ, Chatterjee S, Jiang J, Ehrenshaft M, Lardinois O, Ramirez DC, Tomer KB, Mason RP 2011. Site-specific radical formation in DNA induced by Cu(II)-H2O2 oxidizing system, using ESR, immuno-spin trapping, LC-MS, and MS/MS. Free Radic Biol Med 50: 1536–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Chatterjee S, Jiang J, Sinha BK, Mason RP 2012. Detection and imaging of the free radical DNA in cells: Site-specific radical formation induced by Fenton chemistry and its repair in cellular DNA as seen by electron spin resonance, immuno-spin trapping and confocal microscopy. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 5477–5486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu C, Wagner JR, Cadet J 1996. Photosensitized oxidation of 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine by 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone: Characterization of 5-(hydroperoxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine and stable methyl group oxidation products. J Am Chem Soc 118: 11406–11411 [Google Scholar]

- Bourdat AG, Douki T, Frelon S, Gasparutto D, Cadet J 2000. Tandem base lesions are generated by hydroxyl radical within isolated DNA in aerated aqueous solution. J Am Chem Soc 122: 4549–4556 [Google Scholar]

- Box HC, Budzinski EE, Freund HG, Evans MS, Patrzyc HB, Wallace JC, MacCubbin AE 1993. Vicinal lesions in X-irradiated DNA? Int J Radiat Biol 64: 261–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem R, Karran P 2012. Multiple forms of DNA damage caused by UVA photoactivation of DNA 6-thioguanine. Photochem Photobiol 88: 5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem R, Daehn I, Karran P 2011. Efficient DNA interstrand crosslinking by 6-thioguanine and UVA radiation. DNA Repair 10: 869–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows CJ 2009. Surviving an oxygen atmosphere: DNA damage and repair. ACS Symp Ser Am Chem Soc 2009: 145–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T 2011. Oxidatively generated damage to DNA by UVA radiation in cells and human skin. J Invest Dermat 131: 1005–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Berger M, Buchko GW, Joshi PC, Raoul S, Ravanat JL 1994. 2,2-Diamino-4-[(3,5-di-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5-(2H)-oxazolone: A novel and predominant radical oxidation product of 3′,5′-di-O-acetyl-2′-deoxyguanosine. J Am Chem Soc 116: 7403–7404 [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL 2008. Oxidatively generated damage to the guanine moiety of DNA: Mechanistic aspects and formation in cells. Acc Chem Res 41: 1075–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL, Di Mascio P 2009. Sensitized formation of oxidatively generated damage to cellular DNA by UVA radiation. Photochem Photobiol Sci 8: 903–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL 2010. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA. Free Radic Biol Med 49: 9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL 2011. Measurement of oxidatively generated base damage in cellular DNA. Mutat Res 711: 3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL, Wagner JR 2012a. Measurement of oxidatively generated base damage to nucleic acids in cells: facts and artifacts. Bioanal Rev 10.1007/s12566-012-0029-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Ravanat JL, Wagner JR 2012b. Oxidatively generated nucleobase modifications in isolated and cellular DNA (ed. Chatgilialoglu C, Studer A), pp. 1319–1344 John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Mouret S, Ravanat JL, Douki T 2012c. Photo-induced damage to cellular DNA: Direct and photosensitized reactions. Photochem Photobiol 88: 1048–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Loft S, Olinski R, Evans MD, Bialkowski K, Richard Wagner J, Dedon PC, Møller P, Greenberg MM, Cooke MS 2012d. Biologically relevant oxidants and terminology, classification and nomenclature of oxidatively generated damage to nucleobases and 2-deoxyribose in nucleic acids. Free Radic Res 46: 367–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Ravanat JL, Tavernaporro M, Menoni H, Angelov D 2012e. Oxidatively generated complex DNA damage: Tandem and clustered lesions. Cancer Lett 327: 5–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeias LP, Steenken S 2000. Reaction of HO• with guanine derivatives in aqueous solution: Formation of two different redox-active OH-adduct radicals and their unimolecular transformation reactions. Properties of G(-H)•. Chem A Eur J 6: 475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Jiang Y, Wang Y 2009. Kinetics of deamination and Cu(II)/H2O2/Ascorbate-induced formation of 5-methylcytosine glycol at CpG sites in duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 6635–6643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatgilialoglu C, D’Angelantonio M, Kciuk G, Bobrowski K 2011a. New insights into the reaction paths of hydroxyl radicals with 2′-deoxyguanosine. Chem Res Toxicol 24: 2200–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatgilialoglu C, Ferreri C, Terzidis MA 2011b. Purine 5′,8-cyclonucleoside lesions: Chemistry and biology. Chem Soc Rev 40: 1368–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho BP, Kadlubar FF, Culp SJ, Evans FE 1990. 15N nuclear magnetic resonance studies on the tautomerism of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, 8-hydroxyguanosine, and other C8-substituted guanine nucleosides. Chem Res Toxicol 3: 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke MS, Olinski R, Loft S 2008. Measurement and meaning of oxidatively modified DNA lesions in urine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 17: 3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke MS, Loft S, Olinski R, Evans MD, Bialkowski K, Wagner JR, Dedon PC, Møller P, Greenberg MM, Cadet J 2010. Recommendations for standardized description of and nomenclature concerning oxidatively damaged nucleobases in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol 23: 705–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courdavault S, Baudouin C, Sauvaigo S, Mouret S, Candéias S, Charveron M, Favier A, Cadet J, Douki T 2004. Unrepaired cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers do not prevent proliferation of UV-B-irradiated cultured human fibroblasts. Photochem Photobiol 79: 145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courdavault S, Baudouin C, Charveron M, Canguilhem B, Favier A, Cadet J, Douki T 2005. Repair of the three main types of bipyrimidine DNA photoproducts in human keratinocytes exposed to UVB and UVA radiations. DNA Repair 4: 836–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp SJ, Cho BP, Kadlubar FF, Evans FE 1989. Structural and conformational analyses of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine. Chem Res Toxicol 2: 416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies RJH, Malone JF, Gan Y, Cardin CJ, Lee MPH, Neidle S 2007. High-resolution crystal structure of the intramolecular d(TpA) thymine-adenine photoadduct and its mechanistic implications. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 1048–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedon PC 2008. The chemical toxicology of 2-deoxyribose oxidation in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol 21: 206–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Errico M, Parlanti E, Teson M, De Jesus BMB, Degan P, Calcagnile A, Jaruga P, Bjørås M, Crescenzi M, Pedrini AM, et al. 2006. New functions of XPC in the protection of human skin cells from oxidative damage. EMBO J 25: 4305–4315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Errico M, Parlanti E, Teson M, Degan P, Lemma T, Calcagnile A, Iavarone I, Jaruga P, Ropolo M, Pedrini AM, et al. 2007. The role of CSA in the response to oxidative DNA damage in human cells. Oncogene 26: 4336–4343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S, Kropachev K, Cai Y, Kolbanovskiy M, Durandina SA, Liu Z, Shafirovich V, Broyde S, Geacintov NE 2012. Structural, energetic and dynamic properties of guanine(C8)-thymine(N3) cross-links in DNA provide insights on susceptibility to nucleotide excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 2506–2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Cadet J 2001. Individual determination of the yield of the main UV-induced dimeric pyrimidine photoproducts in DNA suggests a high mutagenicity of CC photolesions. Biochemistry 40: 2495–2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Perdiz D, Gróf P, Kuluncsics Z, Moustacchi E, Cadet J, Sage E 1999. Oxidation of guanine in cellular DNA by solar UV radiation: Biological role. Photochem Photobiol 70: 184–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Court M, Sauvaigo S, Odin F, Cadet J 2000. Formation of the main UV-induced thymine dimeric lesions within isolated and cellular DNA as measured by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem 275: 11678–11685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Angelov D, Cadet J 2001. UV laser photolysis of DNA: Effect of duplex stability on charge-transfer efficiency. J Am Chem Soc 123: 11360–11366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Rivière J, Cadet J 2002a. DNA tandem lesions containing 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and formamido residues arise from intramolecular addition of thymine peroxyl radical to guanine. Chem Res Toxicol 15: 445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Vadesne-Bauer G, Cadet J 2002b. Formation of 2′-deoxyuridine hydrates upon exposure of nucleosides to gamma radiation and UVC-irradiation of isolated and cellular DNA. Photochem Photobiol Sci 1: 565–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Reynaud-Angelin A, Cadet J, Sage E 2003. Bipyrimidine photoproducts rather than oxidative lesions are the main type of DNA damage involved in the genotoxic effect of solar UVA radiation. Biochemistry 42: 9221–9226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Ravanat JL, Angelov D, Wagner JR, Cadet J 2004. Effects of duplex stability on charge transfer efficiency within DNA. Topics Curr Chem 236: 1–25 [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Ravanat JL, Pouget JP, Testard I, Cadet J 2006. Minor contribution of direct ionization to DNA base damage induced by heavy ions. Int J Radiat Biol 82: 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelon S, Douki T, Ravanat JL, Pouget JP, Tornabene C, Cadet J 2000. High-performance liquid chromatography: Tandem mass spectrometry measurement of radiation-induced base damage to isolated and cellular DNA. Chem Res Toxicol 13: 1002–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelon S, Douki T, Cadet J 2002. Radical oxidation of the adenine moiety of nucleoside and DNA: 2-hydroxy-2′-deoxyadenosine is a minor decomposition product. Free Radical Res 36: 499–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparutto D, Ravanat JL, Gérot O, Cadet J 1998. Characterization and chemical stability of photooxidized oligonucleotides that contain 2,2-diamino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone. J Am Chem Soc 120: 10283–10286 [Google Scholar]

- Gimisis T, Cismaş C 2006. Isolation, characterization, and independent synthesis of guanine oxidation products. Eur J Org Chem 2006: 1351–1378 [Google Scholar]

- Gueranger Q, Kia A, Frith D, Karran P 2011. Crosslinking of DNA repair and replication proteins to DNA in cells treated with 6-thioguanine and UVA. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 5057–5066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiser K, Fingerhut BP, Heil K, Glas A, Herzog TT, Pilles BM, Schreier WJ, Zinth W, Devivie-Riedle R, Carell T 2012. Mechanism of UV-induced formation of Dewar lesions in DNA. Angew Chem Int Ed 51: 408–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM, Cadet J 2012. It's all about position: The basal layer of human epidermis is particularly susceptible to different types of sunlight-induced DNA damage. J Invest Dermat 132: 265–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins CL, Davies MJ 2001. Hypochlorite-induced damage to nucleosides: Formation of chloramines and nitrogen-centered radicals. Chem Res Toxicol 14: 1071–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins CL, Davies MJ 2002. Hypochlorite-induced damage to DNA, RNA, and polynucleotides: Formation of chloramines and nitrogen-centered radicals. Chem Res Toxicol 15: 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In SH, Carter KN, Sato K, Greenberg MM 2007. Characterization and mechanism of formation of tandem lesions in DNA by a nucleobase peroxyl radical. J Am Chem Soc 129: 4089–4098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K, Jin SG, Pfeifer GP, Szabó PE 2011. Reprogramming of the paternal genome upon fertilization involves genome-wide oxidation of 5-methylcytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 3642–3647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C, Zhang Y 2011. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science 333: 1300–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P, Xiao Y, Nelson BC, Dizdaroglu M 2009. Measurement of (5′R)- and (5′S)-8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosines in DNA in vivo by liquid chromatography/isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 386: 656–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Hong H, Cao H, Wang Y 2007. In vivo formation and in vitro replication of a guanine-thymine intrastrand cross-link lesion. Biochemistry 46: 12757–12763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SG, Jiang Y, Qiu R, Rauch TA, Wang Y, Schackert G, Krex D, Lu Q, Pfeifer GP 2011. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is strongly depleted in human cancers but its levels do not correlate with IDH1 mutations. Cancer Res 71: 7360–7365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai K, Nishimura S 1983. Hydroxylation of deoxyguanosine by reducing agents in the presence of oxygen. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 12: 165–167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanishi S, Murata M 2006. Mechanism of DNA damage induced by bromate differs from general types of oxidative stress. Toxicology 221: 172–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielbassa C, Roza L, Epe B 1997. Wavelength dependence of oxidative DNA damage induced by UV and visible light. Carcinogenesis 18: 811–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchakdjian M, Bodepudi V, Shibutani S, Eisenberg M, Johnson F, Grollman AP, Patel DJ 1991. NMR structural studies of the ionizing radiation adduct 7-hydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine (8-oxo-7H-dG) opposite deoxyadenosine in a DNA duplex. 8-Oxo-7H-dG(syn)•dA(anti) alignment at lesion site. Biochemistry 30: 1403–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus TF, Globisch D, Wagner M, Eigenbrod S, Widmann D, Münzel M, Müller M, Pfaffeneder T, Hackner B, Feiden W, et al. 2012. Low values of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), the “sixth base,” are associated with anaplasia in human brain tumors. Int J Cancer 131: 1577–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, Heintz N 2009. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in purkinje neurons and the brain. Science 324: 929–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttappan-Nair V, Samson-Thibault F, Wagner JR 2010. Generation of 2′-deoxyadenosine N6-aminyl radicals from the photolysis of phenylhydrazone derivatives. Chem Res Toxicol 23: 48–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YA, Yun BH, Kim SK, Margolin Y, Dedon PC, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V 2007. Mechanisms of oxidation of guanine in DNA by carbonate radical anion, a decomposition product of nitrosoperoxycarbonate. Chem A Eur J 13: 4571–4581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenton KJ, Therriault H, Fülöp T, Payette H, Wagner JR 1999. Glutathione and ascorbate are negatively correlated with oxidative DNA damage in human lymphocytes. Carcinogenesis 20: 607–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Furtmüller PG, Sattler W, Obinger C 2007. Myeloperoxidase: A target for new drug development? Br J Pharmacol 152: 838–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Suzuki T, Friesen MD, Ravanat JL, Cadet J, Pignatelli B, Nishino H, Ohshima H 2001. Chlorination of guanosine and other nucleosides by hypochlorous acid and myeloperoxidase of activated human neutrophils: Catalysis by nicotine and trimethylamine. J Biol Chem 276: 40486–40496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter B, Malejka-Giganti D, Csallany AS, Tretyakova N 2006. Quantitative analysis of the oxidative DNA lesion, 2,2-diamino-4-(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl) amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone (oxazolone), in vitro and in vivo by isotope dilution-capillary HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 5449–5460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medinas DB, Cerchiaro G, Trindade DF, Augusto O 2007. The carbonate radical and related oxidants derived from bicarbonate buffer. IUBMB Life 59: 255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misiaszek R, Crean C, Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V 2004. Oxidative DNA damage associated with combination of guanine and superoxide radicals and repair mechanisms via radical trapping. J Biol Chem 279: 32106–32115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Dizdaroglu M 1994. Ionizing radiation causes greater DNA base damage in radiation-sensitive mutant M10 cells than in parent mouse lymphoma L5178Y cells. Radiat Res 140: 85–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouret S, Baudouin C, Charveron M, Favier A, Cadet J, Douki T 2006. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are predominant DNA lesions in whole human skin exposed to UVA radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 13765–13770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouret S, Charveron M, Favier A, Cadet J, Douki T 2008. Differential repair of UVB-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in cultured human skin cells and whole human skin. DNA Repair 7: 704–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouret S, Philippe C, Gracia-Chantegrel J, Banyasz A, Karpati S, Markovitsi D, Douki T 2010. UVA-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in DNA: A direct photochemical mechanism? Org Biomol Chem 8: 1706–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouret S, Leccia MT, Bourrain JL, Douki T, Beani JC 2011. Individual photosensitivity of human skin and UVA-induced pyrimidine dimers in DNA. J Invest Dermat 131: 1539–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouret S, Forestier A, Douki T 2012. The specificity of UVA-induced DNA damage in human melanocytes. Photochem Photobiol Sci 11: 155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel M, Globisch D, Brückl T, Wagner M, Welzmiller V, Michalakis S, Müller M, Biel M, Carell T 2010. Quantification of the sixth DNA base hydroxymethylcytosine in the brain. Angew Chem Int Ed 49: 5375–5377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel M, Globisch D, Carell T 2011. 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, the sixth base of the genome. Angew Chem Int Ed 50: 6460–6468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeley WL, Essigmann JM 2006. Mechanisms of formation, genotoxicity, and mutation of guanine oxidation products. Chem Res Toxicol 19: 491–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura S 2011. 8-Hydroxyguanine: A base for discovery. DNA Repair (Amst) 10: 1078–1083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Uesugi S, Ikehara M, Nishimura S, Kawase Y, Ishikawa H, Inoue H, Ohtsuka E 1991. NMR studies of a DNA containing 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 1407–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier S, Hau J, Gasparutto D, Cadet J, Favier A, Ravanat JL 2006. Characterization of lysine-guanine cross-links upon one-electron oxidation of a guanine-containing oligonucleotide in the presence of a trilysine peptide. J Am Chem Soc 128: 5703–5710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffeneder T, Hackner B, Truß M, Münzel M, Müller M, Deiml CA, Hagemeier C, Carell T 2011. The discovery of 5-formylcytosine in embryonic stem cell DNA. Angew Chem Int Ed 50: 7008–7012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer GP, You YH, Besaratinia A 2005. Mutations induced by ultraviolet light. Mutat Res 571: 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget JP, Frelon S, Ravanat JL, Testard I, Odin F, Cadet J 2002. Formation of modified DNA bases in cells exposed either to gamma radiation or to high-LET particles. Radiat Res 157: 589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratviel G, Meunier B 2006. Guanine oxidation: One- and two-electron reactions. Chem A Eur J 12: 6018–6030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanat JL, Di Mascio P, Martinez GR, Medeiros MHG, Cadet J 2000. Singlet oxygen induces oxidation of cellular DNA. J Biol Chem 275: 40601–40604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanat JL, Saint-Pierre C, Di Mascio P, Martinez GR, Medeiros MHG, Cadet J 2001. Damage to isolated DNA mediated by singlet oxygen. Helv Chim Acta 84: 3702–3709 [Google Scholar]

- Ravanat JL, Sauvaigo S, Caillat S, Martinez GR, Medeiros MHG, Di Mascio P, Favier A, Cadet J 2004. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to cellular DNA determined by the comet assay associated with DNA repair enzymes. Biol Chem 385: 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulus P, Spessotto S, Gateau M, Cadet J, Favier A, Ravanat JL 2004. Detection of new radiation-induced DNA lesions by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 18: 2223–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulus P, Duroux B, Bayle PA, Favier A, Cadet J, Ravanat JL 2007. Oxidation of the sugar moiety of DNA by ionizing radiation or bleomycin could induce the formation of a cluster DNA lesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 14032–14037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivière J, Bergeron F, Tremblay S, Gasparutto D, Cadet J, Wagner JR 2004. Oxidation of 5-hydroxy-2′-deoxyuridine into isodialuric acid, dialuric acid, and hydantoin products. J Am Chem Soc 126: 6548–6549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivière J, Klarskov K, Wagner JR 2005. Oxidation of 5-hydroxypyrimidine nucleosides to 5-hydroxyhydantoin and its α-hydroxy-ketone isomer. Chem Res Toxicol 18: 1332–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivière J, Ravanat JL, Wagner JR 2006. Ascorbate and H2O2 induced oxidative DNA damage in Jurkat cells. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 2071–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo JL, Dunn J, Rees A, Rünger TM 2011. No formation of DNA double-strand breaks and no activation of recombination repair with UVA. J Invest Dermat 131: 1139–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson-Thibault F, Madugundu GS, Gao S, Cadet J, Wagner JR 2012. Analysis of cytosine modifications in oxidized DNA by enzymatic digestion and HPLC-MS/MS. Chem Res Toxicol 25: 1902–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sczepanski JT, Jacobs AC, Majumdar A, Greenberg MM 2009. Scope and mechanism of interstrand cross-link formation by the C4′-oxidized abasic site. J Am Chem Soc 131: 11132–11139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sczepanski JT, Hiemstra CN, Greenberg MM 2011. Probing DNA interstrand cross-link formation by an oxidized abasic site using nonnative nucleotides. Bioorg Med Chem 19: 5788–5793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu C, Foote CS 1993. Endoperoxide formation in a guanosine derivative. J Am Chem Soc 115: 10446–10447 [Google Scholar]

- Su DGT, Taylor JSA, Gross ML 2010. A new photoproduct of 5-methylcytosine and adenine characterized by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol 23: 474–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, et al. 2009. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 324: 930–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari A, Sarkany RP, Young AR 2012. UVA1 induces cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers but not 6–4 photoproducts in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermat 132: 394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp C, Reite K, Klungland A, Epe B 2007. Deficiency of the Cockayne syndrome B (CSB) gene aggravates the genomic instability caused by endogenous oxidative DNA base damage in mice. Oncogene 26: 4044–4048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay S, Wagner JR 2008. Dehydration, deamination and enzymatic repair of cytosine glycols from oxidized poly(dG-dC) and poly(dI-dC). Nucleic Acids Res 36: 284–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay S, Douki T, Cadet J, Wagner JR 1999. 2′-Deoxycytidine glycols, a missing link in the free radical-mediated oxidation of DNA. J Biol Chem 274: 20833–20838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay S, Gantchev T, Tremblay L, Lavigne P, Cadet J, Wagner JR 2007. Oxidation of 2′-deoxycytidine to four interconverting diastereomers of N1carbamoyl-4,5-dihydroxy-2-oxoimidazolidine nucleosides. J Org Chem 72: 3672–3678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatatesmarlu D, Leszczynski J 1998. Tautomerism equilibria in 8-oxopuirines: Implication for mutagenesis. J Comput Aided Mol Des 12: 373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira AJSC, Steenken S 1990. Pattern of OH radical reaction with adenine and its nucleosides and nucleotides: Characterization of two types of isomeric OH adduct and their unimolecular transformation reactions. J Am Chem Soc 112: 6986–6994 [Google Scholar]

- von Sonntag C 2006. Free-radical-induced DNA damage and its repair. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JR, Cadet J 2010. Oxidation reactions of cytosine DNA components by hydroxyl radical and one-electron oxidants in aerated aqueous solutions. Acc Chem Res 43: 564–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JR, Hu CC, Ames BN 1992. Endogenous oxidative damage of deoxycytidine in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 89: 3380–3384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JR, van Lier JE, Berger M, Cadet J 1994. Thymidine hydroperoxides: Structural assignment, conformational features, and thermal decomposition in water. J Am Chem Soc 116: 2235–2242 [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JR, Decarroz C, Berger M, Cadet J 1999. Hydroxyl-radical-induced decomposition of 2′-deoxycytidine in aerated aqueous solutions. J Am Chem Soc 121: 4101–4110 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Taylor JS, Gross ML 2001. Isolation and mass spectrometric characterization of dimeric adenine photoproducts in oligodeoxynucleotides. Chem Res Toxicol 14: 738–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yuan B, Guerrero C, Bahde R, Gupta S, Wang Y 2011. Quantification of oxidative DNA lesions in tissues of Long-Evans Cinnamon rats by capillary high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with stable isotope-dilution method. Anal Chem 83: 2201–2209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Clauson CL, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Wang Y 2012. The oxidative DNA lesions 8,5′-cyclopurines accumulate with aging in a tissue-specific manner. Aging Cell 11: 714–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC 2008. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat Chem Biol 4: 278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Zhang Y 2011. Mechanisms and functions of Tet protein mediated 5-methylcytosine oxidation. Genes Dev 25: 2436–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun BH, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V 2011. Generation of guanine-thymidine cross-links in DNA by peroxynitrite/carbon dioxide. Chem Res Toxicol 24: 1144–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lu X, Lu J, Liang H, Dai Q, Xu GL, Luo C, Jiang H, He C 2012. Thymine DNA glycosylase specifically recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine-modified DNA. Nat Chem Biol 8: 328–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]