Abstract

We conducted a community based, randomized control trial of Promoting First Relationships (PFR; Kelly, Sandoval, Zuckerman, & Buehlman, 2008) to improve parenting and toddler outcomes for toddlers in state dependency. Toddlers (10 – 24 months; N = 210) with a recent placement disruption were randomized to 10-week PFR or a comparison condition. Community agency providers were trained to use PFR in the intervention for caregivers. From baseline to post-intervention follow-up, observational ratings of caregiver sensitivity improved more in the PFR condition than in the comparison condition, with an effect size for the difference in adjusted means post-intervention of d = .41. Caregiver understanding of toddlers’ social emotional needs and caregiver reports of child competence also differed by intervention condition post-intervention (d = .36 and d = .42) with caregivers in the PFR condition reporting more understanding of toddlers and child competence. Models of PFR effects on within-individual change were significant for caregiver sensitivity and understanding of toddlers. At the 6-month follow-up 61% of original sample dyads were still intact and there were no significant differences on caregiver or child outcomes, although caregivers in the PFR group did report marginally (p<.10) fewer child sleep problems (d = −.34).

Keywords: parent-infant dyads, intervention research, children in child welfare, home visiting, foster care, clinical trials

Infants and toddlers are a growing population in child welfare. Between 2000 and 2010, the percentage of maltreated children in child welfare who were under three years old increased from 15.7% to 27.3% (Administration for Children and Families, 2000, 2010). In the first year of life, human infants are biologically primed to develop primary attachments to their parents, from whom they seek comfort and nurturance, and who are critical to the development of early regulatory capacity (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Siegel, 2001). Maltreatment, subsequent out-of-home placement, and multiple moves in care result in disruptions of primary attachment relationships that are critical to later social and emotional functioning (Sroufe, 1988). For infants and toddlers in child welfare state dependency, risks associated with the lack of protection in their birth family that led to child welfare involvement may be compounded by sequential separation from one or more attachment figures during this critical period of rapid physiological, neurological, and developmental maturation (Rubin et al., 2004; Rubin, O’Reilly, Luan, & Localio, 2007). In a recent plea for developmentally informed foster care for maltreated infants and young children, Zeanah, Shauffer, and Dozier (2011) emphasized that attachment must be of paramount consideration in child welfare planning, decision making, and training of foster care providers and parents. In accord with a call to action from Zeanah and colleagues (2011), we report on the results of a randomized control study of a brief intervention to help caregivers promote secure attachments and emotional regulation for toddlers in child welfare. This is the first randomized trial of the intervention and training program, Promoting First Relationships (PFR; Kelly, Sandoval, Zuckerman, & Buehlman, 2008).

Multiple Placements and Attachment Disruptions

Infants in child welfare must develop a new attachment relationship with each placement. Bowlby (1969/1982) showed how very young children grieve when attachment relationships are disrupted, even when the children receive excellent care. Infants younger than 12 months tend to seek comfort and closeness from new attachment figures within a week of placement, but toddlers older than a year do not readily seek out their new attachment figures, and may be inconsolable or push them away (Stovall-McClough & Dozier, 2004). The process of attachment formation in toddlers and older children is complicated by these difficult child behaviors, which may be exacerbated if there are serial placements resulting in multiple caregiver changes. These events can compound the effects of early maltreatment and lead to mental health problems. Placement instability increases the risk of later internalizing and externalizing disorders for children with initially normative levels of these problems (Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000). However, caregiver sensitivity and understanding of the meaning of the child’s behavior is associated with child attachment security, even for older toddlers and preschoolers with a child welfare history (Stovall-McClough & Dozier, 2004).

Because they experienced disturbed or disrupted primary relationships, many infants and toddlers in child welfare or foster care are less able to use their caregivers to buffer or regulate stress than infants with consistent caregivers, and are more likely to develop insecure or disorganized attachments which contribute to regulatory problems (Dozier, Higley, Albus, & Nutter, 2002). The pervasive effects of early separation from caregivers may be compounded by other risk factors. Infants who enter foster care as newborns have elevated rates of low birth weight, birth abnormalities, lack of prenatal care, and exposure to drugs, alcohol, and other teratogens (Klee, Kronstadt, & Zlotnick, 1997; Putnam-Hornstein & Needell, 2011). These factors compromise infants’ regulatory capacities and pose additional challenges to caregivers (Klee et al., 1997). Regulatory problems in infancy have significant costs as these children continue to differ from peers in mood regulation, sensory integration, motor control, sleep, and behavioral control as they get older (Degangi, Breinbauer, Doussard, Porges, & Greenspan, 2000).

Foster mothers more frequently report that their children are difficult to calm or soothe than mothers of children who have never been in care (Tyrrell & Dozier, 1999). Because infants with disrupted attachments do not elicit care in expectable ways, they are regarded as difficult by caregivers (Dozier et al., 2002). Toddlers in foster care often behave in avoidant or resistant ways when hurt or frightened, and their caregivers respond “in kind“ (Stovall-McClough & Dozier, 2004) by ignoring or getting angry. Evidence-based interventions, informed by the attachment literature, are needed to help caregivers to provide care that promotes security for this vulnerable population of children.

Conceptual Framework for Interventions to Promote Attachment Security

A primary concept undergirding effective, attachment-based interventions is caregiver sensitivity. De Wolff and van IJzendoorn (1997) conducted a meta-analysis of 21 studies (N = 1,099) that assessed maternal sensitivity and child attachment security using observational measures. Results showed a combined effect size of r = .24 for the association between the two. Thus, sensitivity is an important (but not exclusive) condition of attachment security, and should be a focus in interventions to promote attachment security. In a meta-analysis of 51 randomized controlled studies of attachment-based interventions, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, and Juffer (2003) found that brief interventions that used video feedback techniques and a focus on promoting positive parent-child interactions were most effective in improving caregiver sensitivity, and that interventions that had a moderate to large effect on sensitivity also improved child attachment security.

Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, and van IJzendoorn (2008) summarize why video feedback is a potent intervention. When video feedback is strengths-based, as in PFR, the provider delivering the intervention highlights instances of sensitive nurturance, thereby increasing caregiver awareness, confidence and competence. When the interaction is not going well and the child is behaving in challenging ways, the provider, in a sensitive manner, helps the caregiver notice, reflect on and interpret the meaning of the child’s behavior. From this perspective the provider helps the caregiver acquire a deeper understanding of developmentally appropriate expectations of the child and reframe the meaning of challenging behaviors as revealing the child’s need for the caregiver’s sensitive and nurturing care to regulate or repair the interaction. Considerable research indicates that reflective video feedback improves parents’ sensitive responsiveness because it increases their ability to think about the feelings and needs underlying their child’s behavior, to attune to the child’s positive and negative emotions, and to understand and respond appropriately to attachment versus exploratory behavior (Juffer et al., 2008).

Video feedback used in reflective ways helps caregivers appropriately understand the mind of the developing child, an ability which in turn is associated with attachment security (Meins, Fernyhough, Fradley, & Tuckey, 2001). Grienenberger, Kelly, and Slade (2005) showed how the effect of maternal reflective ability on child attachment security was mediated by maternal sensitivity. Lieberman (2003) studied adoptive parents who had concerns about their children’s ability to attach to them. She found that parents missed or overlooked child cues of need for care, including misinterpreting the meaning of tantrums, defiance and noncompliance as signs that the children did not care for them, rather than as expressions of anxiety and fear of loss. Parents often responded with disciplinary measures such as “time out” when they perceived the children’s behavior was inappropriate, instead of responding with firm but comforting behavior that would have reassured the children about the parents’ ongoing availability. Similar challenges, further exacerbated by parental guilt, anxiety, and fear of loss, are faced by birth parents being reunified with their young children after a period in foster care during which the children developed attachments to other caregivers.

A brief attachment-based intervention for infants and toddlers in the child welfare system that has been tested in a randomized control trial is Dozier’s Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC; Dozier & Infant-Caregiver Lab, 2003). ABC is designed to help caregivers provide nurturance when they would not naturally do so and when infants do not signal their needs. In preliminary results, foster parents who received ABC reported less avoidance on the part of their children after distressful episodes, but no differences in secure behaviors (Dozier et al., 2009). Other than Dozier’s pioneering work, to our knowledge no additional brief interventions have been tested for infants and toddlers in foster care, perhaps because the behavioral problems of infants and toddlers are less apparent and more manageable than those of older children in care. While we know infants in child welfare are at high risk for long-term and short-term effects of disruptions in attachment relationships, their mental health problems do not demand attention until they are older.

Promoting First Relationships (PFR)

PFR was developed in the late 1990’s and has been a popular infant mental health training program for workers in early intervention, community mental health, home visiting, and early care and education in Washington State. Quasi-experimental studies of PFR have shown promising increases in sensitivity (Kelly, Buehlman, & Caldwell, 2000; Kelly, Zuckerman, & Rosenblatt, 2008) and in child attachment security (Kelly, 2007) among dyads who have received the intervention. PFR includes many of the effective elements of brief attachment-based interventions summarized by Bakermans-Kranenburg and colleagues (2003). (These attachment-based interventions should not to be confused with ‘attachment therapies’ that have been criticized by Chaffin and colleagues (2006), as part of a task force of the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children). In conjunction with video feedback, PFR uses reflective practice principals (Slade, Sadler, & Mayes, 2005; Suchman et al., 2010) to focus on the deeper emotional feelings and needs underlying difficulties in the parent and child relationship and to help caregivers think about their child’s developing mind. For this study, PFR also addressed the fact that infants and toddlers in child welfare tend to give behavioral signals that lead even nurturing caregivers to provide non-nurturing care (Dozier et al., 2002). PFR helps caregivers identify possible ‘miscues,’ empathize with the child’s underlying distress, and reframe or understand the child’s behavior as reflecting an unmet need. This better understanding of the child’s cues should, in turn, lead to more responsive, nurturing care.

Current Study

In 2005 the researchers invited community stakeholders (child welfare workers and administrators, judges, mental health and public health agency directors, parents, and early intervention workers) to identify and discuss a problem that could be addressed in a research proposal in response to an NIH program announcement, PAR-05-026, Community Participation in Research. Community stakeholders focused on infants and toddlers in foster care. They indicated a desire for PFR to be tested for use with caregivers of infants and toddlers in state dependency. They acknowledged that a randomized control design would be optimal.

This is the first randomized trial of PFR. It fills a gap in our knowledge because there are few or no community-based trials of attachment interventions appropriate for toddlers in state dependency. In our model of change, PFR would increase caregiver awareness of children’s behavioral cues and miscues for nurturance. PFR would also improve caregiver understanding that difficult toddler behavior reflects unmet social emotional needs. In turn, caregiver sensitivity would improve and children would become more secure and engaged in their primary relationships, and more behaviorally and emotionally regulated. We hypothesized that PFR, as used by community providers, would result in improved parenting and child outcomes relative to a comparison condition in which families received home-based services that were not relationship-focused.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and ten toddlers and their caregivers were recruited into the Fostering Families Project (FFP) between April of 2007 and March of 2010. Recruitment into the study involved close collaboration between research study personnel, the state Institutional Review Board, and the state Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS). The study supported an authorized worker within DSHS to access DSHS records and identify infants in one county between the ages of 10 and 24 months who had experienced a court-ordered placement that resulted in a change in primary caregiver within the prior seven weeks. Permission to contact caregivers about the project was obtained from a Department of Child and Family Services (DCFS) social worker, after which a research team social worker made the contact, determined eligibility, and scheduled the baseline research visit. Eligible caregivers spoke English and could be foster parents, biological parents, or adult kin. The caregiver and child were assessed at baseline, received intervention services, and then were assessed post-intervention and six months later if they were still in the same household. (Children were also assessed with new caregivers if they had experienced a placement change, but dyads with new caregivers are not included in these analyses.) Caregivers were compensated $75 for each research visit, but received no compensation for intervention visits.

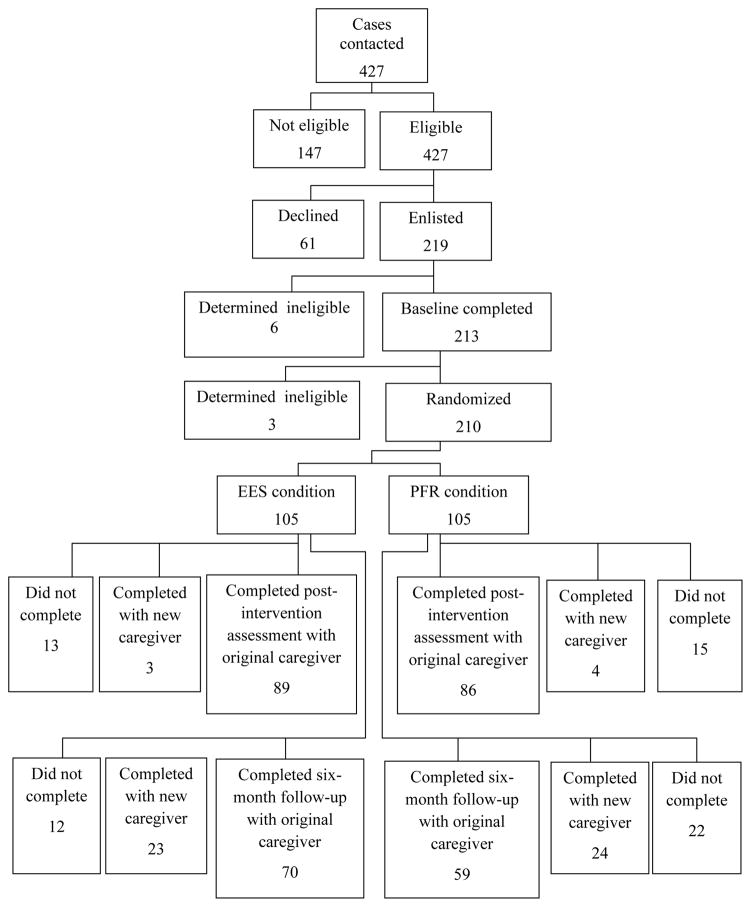

Randomization into the Promoting First Relationships (PFR) intervention and the Early Education Support (EES) comparison condition was computer generated, blocked by caregiver type. Of the 210 infants who were randomized, 29 (13.8%) (18 in EES and 11 in PFR) experienced a placement change within four months after study enrollment. For these infants, the new caregiver agreed to participate in the study. A new baseline assessment was conducted and the dyad remained in the intervention condition to which the infant was initially assigned. The flow of participant recruitment, assignment and attrition over time is shown in Figure 1. Demographic and background characteristics of the 210 toddlers and caregivers included in the analysis sample are shown in Table 1. Most toddlers in the sample experienced multiple placement changes prior to enrollment in the study, and there were substantial numbers of three types of caregivers: birth parents (five fathers), kin, and foster. There were no differences by condition on any demographic variable, with the exception that more PFR infants experienced two or more removals from their birth home, X2(1) = 7.31, p< .01, N = 210.

Figure 1.

Flow of participant recruitment, assignment and attrition over time

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Intervention Condition

| EES (n=105) | PFR (n=105) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| n (%) | n (%) | |

|

|

||

| Infant male | 55 (52.4) | 63 (60) |

| Infant Hispanic | 12 (11.4) | 9 (8.6) |

| Infant race | ||

| Native American/Alaskan native | 5 (4.8) | 9 (8.6) |

| Black | 14 (13.3) | 17 (16.2) |

| Mixed race | 18 (17.1) | 23 (21.9) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 2 (1.9) |

| Unable to determine | 4 (3.4) | 3 (2.9) |

| White | 65 (61.9) | 51 (48.6) |

| Removed from birth parent home more than once* | 5 (4.8) | 17 (16.2) |

| Caregiver type | ||

| Biological parent | 29 (27.6) | 27 (25.7) |

| Kin | 30 (28.6) | 35 (33.3) |

| Foster parent | 46 (43.8) | 43 (41.0) |

| Household income <$20,000 per year | 27 (26.5) | 23 (23.0) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Infant age in months | 18.06 (4.49) | 17.96 (4.97) |

| Infant age in months at first removal | 10.86 (7.07) | 10.73 (7.78) |

| Number of caregiver changes since birth | 2.70 (1.51) | 2.67 (1.66) |

| Caregiver age in years | 36.50 (10.95) | 35.39 (10.98) |

| Caregiver years of education | 12.93 (1.79) | 13.11 (2.10) |

Note.

= p< .05

Interventions, Dosage, and Fidelity

The providers who delivered the PFR and EES interventions were selected by the directors of five community agencies. One agency provided three EES providers over the course of the project, and four agencies provided five PFR providers over the course of the project. The providers’ time spent training and delivering the interventions was supported by university subcontracts to their respective agencies. All providers also had other caseloads in their agencies.

PFR

Seventy one percent of the 105 caregivers in the PFR condition received all ten weekly sessions of the intervention. Seven percent had none, 20% had fewer than half, and 3% had more than half. The sessions were 60- to 75-minutes long and took place in caregivers’ homes, guided by one of five concurrently working masters-prepared providers. The sessions were designed for this project and covered activities and instructional content in the PFR manual, although the pace of delivery of these components was tailored to individual caregivers. There were five videotaped caregiver-child interactions used for reflective video feedback. These tapes were viewed together by the caregiver and the intervention provider, who guided discussion focusing on parenting strengths and interpretation of the child’s cues. Weeks 2 through 10 began with reflecting on the prior week’s content. During the course of the ten sessions, providers and caregivers reviewed up to 15 handouts on topics such as ‘Staying Connected During Difficult Moments’. They discussed two short videos, ‘Attachment Story’ and ‘Elements of a Healthy Relationship,’ and reflected on topics such as ‘Memory of a Strong Emotion’.

EES

The comparison intervention condition consisted of three monthly 90-minute visits and 81% of the 105 caregivers in the EES condition received complete dosage of the intervention; four percent had no EES visits and 15% had only one or two. Visits occurred in caregivers’ homes and were led by one of three serially employed bachelors-prepared providers from one community agency over the course of the four years of the project. The EES provider helped to connect the family to resources such as Early Head Start, early intervention, housing, mental health services, and child care; the provider also suggested activities to promote growth and development.

Training PFR providers

Training involved 90 hours over six months and consisted of a three-day, large-group introduction to the PFR curriculum followed by completion of three ten-week, mentored PFR interventions with families. The provider first shadowed, then co-led, and then led, the PFR home visits with one of two university-based masters-prepared PFR trainers. Topics in the manualized PFR curriculum include: 1) theories of attachment; 2) social and emotional needs specific to the infant-toddler period and young children who have had disrupted attachments; 3) caregiving that promotes secure infant attachment and emotion regulation (individualized attention; empathy, labeling and organizing feelings and emotions; and predictability); 4) caregiving that promotes healthy identity formation in the toddler years (managing feelings of distress; offering rituals and routines; encouraging exploration, independence, and cooperation through appropriate choices and limits); 5) intervening with challenging behaviors (assessing through discussions and observations; identifying young children’s feelings and unmet social emotional needs; identifying possible causes for challenging behaviors; reframing the behaviors for caregiver; developing individualized intervention plans); and 6) building parents own reflective capacity by exploring the parent’s own sense of self, emotion regulation and supports that influence caregiving. In addition providers practiced the PFR Ways of Being (establishing an emotional connection with the caregiver; sensitive interviewing; reflective observation; and the four specific consultation strategies of positive feedback, positive and instructive feedback, reflective questions or comments, and validating responsive statements). During the mentored PFR training visits and throughout the project, the providers were guided by a weekly reflective consultation group led by a PFR trainer. The consultation group members adhered to the PFR ways of being with each other to provide a parallel process experience of the way we wanted providers to be with families. This reflective consultation model is central to PFR and infant mental health practice (Gilkerson & Kopel, 2005).

Fidelity coding of video feedback sessions

Providers videotaped or audio recorded (which providers preferred) three video feedback sessions per family. The recordings were rated for providers’ fidelity to PFR. There were three aspects to the fidelity coding. First, a rater who was also a PFR trainer coded each provider’s comments as being either one of the four PFR consultation strategies (positive feedback; positive and instructive feedback; reflective comment or question; or validating, responsive statement) or other. The rater recorded the ratio of PFR reflective consultation strategies to other comments. Second, the rater categorized the predominant focus of each minute of the segment as being on the dyadic relationship; child; or caregiver. Third, the rater assigned the segment a global rating from 1 = “no PFR ways of being used, provider not relationship-focused” to 5 = “Provider using all PFR strategies, is solidly focused on the dyadic relationship, makes the reflective dialogue rich and meaningful for the caregiver”. To pass fidelity, the provider needed a four to one ratio of PFR consultation strategies to other comments, be predominantly focused on the relationship in 90% of the minutes coded, and receive a 4 or higher on the global rating. If a provider received three global ratings in a row of 3 or below, the PFR trainer engaged in weekly individualized remediation with that provider. During remediation the provider did not receive any new cases but continued to provide services to the provider’s current caseload. Fidelity to consultation strategies was reassessed three times before new cases were referred to the provider. Early in the project, two PFR providers entered into this remediation process. One provider resumed cases after two months. The second provider, after seven months of remediation, accepted a mutual agreement between the researchers and her agency to no longer provide services to the project. No other providers required remediation, and no provider received lower than a 4 in the second two years of the project. The mean ratio of PFR reflective consultation strategies to other comments across all providers and cases was 15:1 (range 3:1 to 30:1). The mean fidelity score was 4.04 (SD = .76, range = 3–5). The agency delivering EES understood that it was delivering a comparison intervention that did not have an explicit focus on the caregiver-child relationship. The EES provider submitted audio recorded EES home visits for coding according to the fidelity plan outlined above. In most cases the majority of comments were coded as “other” and the conversation was predominantly not focused on the relationship between caregiver and child. The average EES ratio across all three providers was 1 PFR consultation strategy to 30 other comments (range 1:14 – 1:30). All EES fidelity sessions received a global rating of 1, indicating that no PFR strategies were used.

Fidelity to PFR protocol

The second measure of fidelity assessed the delivery of weekly PFR activities. Providers checked completed activities after each session. For each provider, the indicator was number of activities checked divided by the total activities in the protocol for the PFR sessions actually completed. Providers followed the protocol almost all the time; 97% of activities assigned for weeks completed were checked.

Measures and Procedure

Infants and their caregivers were assessed in two-hour research home visits at baseline (enrollment), post-intervention, and a 6-month follow-up after post-intervention. Visits included interviews, self-report measures, and videotaped caregiver-child interactions, including a brief separation when the caregiver went outside for three minutes (or fewer if the child was distressed). When the child experienced a caregiver change following the intervention, later assessments were completed with the new caregiver. In the current study, only data from visits with infant-caregiver dyads that remained intact since baseline are used, resulting in a sample size of 175 at post-intervention and 129 at the six month follow-up; 123 had the same caregiver at all three time points (58.6% of the original sample).

Dyads that were intact and assessed at post-intervention did not differ (p < .05) from dyads that experienced a caregiver change or did not complete the post-intervention follow-up with respect to intervention condition, gender of the child, caregiver type (foster, kin or birth), whether the infant had experienced multiple removals from their birth home, or number of caregiver changes experienced by the infant prior to enrollment. Intact dyads assessed at the post-intervention time point were younger, M = 17.62 vs. M = 19.98, t (208) = 2.74, p = .007, and were more likely to have completed all sessions of the intervention entailed by their condition assignment, 90.3% vs. 2.9%, X2(1) = 121.25, p <.001, N = 210. For the 86 PFR dyads intact at the post-intervention time point, 86% received the full PFR dose, 2% received nothing, 9% received less than half, and 2% received more than half but not the full dose. At six month follow-up, assessed intact dyads no longer differed with respect to infant age compared to noncompleters or infants with new caregivers, but did differ with respect to caregiver type at baseline, X2(2) = 7.66, p = .022, N = 210, with intact completers more likely to be headed by birth parents (33% vs. 16%) and less likely to have been headed by a foster parent (38% vs. 49%). Intact completers at six month follow-up were again more likely to have completed their intervention than were attriters or dyads with new caregivers, 87% vs. 58%, X2 (1) = 22.44, p < .001, N = 210. For the 59 PFR dyads intact at the post-intervention time point, 85% received the full dose, 2% received nothing, 10% received less than half, and 3% received more than half but not the full dose. The post-intervention assessment was closer to baseline in the EES condition than in the PFR condition, EES: M (SD) = 2.88 (0.93) months; PFR: M (SD) = 4.12 (1.36); t (173) = 7.05, p < .001. Also, months between baseline and the 6-month follow-up differed by condition, EES: M (SD) = 8.85 (0.97); PFR: M (SD) = 10.05 (1.59); t (127) = 5.25, p < .001).

Caregiver outcomes

Our primary outcome was sensitivity measured by a modified total score of the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS; Barnard, 1994), a videotaped interaction to assess caregiver sensitivity, stimulation of the child, and emotional responsiveness. An extensive literature supports its predictive validity of cognitive and social emotional outcomes (Oxford & Spieker, 2006) and sensitivity to intervention effects (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003). The current NCATS total score was initially developed on a nationally representative data set with over 8,000 cases using a combination of item response theory models and multidimensional scaling which reduced the set of 73 items to a set of 27 (personal communication, Monica Oxford). Six of the 27 items measure the caregiver’s response to distress; because not all children displayed distress, these items were not used in the total score. The remaining items represent aspects of positive interaction and indicators of mutuality (e.g. contingency, gaze, and positive affect), caregiver verbal and nonverbal support of child, and sensitive instruction during the teaching task. Sample items include: “caregiver laughs or smiles at the child during the teaching interaction”; “caregiver avoids making critical or negative comments about the child’s task performance”. Items were scored yes or no, and yes scores were summed. Cronbach’s alpha for the sensitivity scale ranged from .71 to .79. A single coder was trained to reliability by a certified NCATS instructor and passed quarterly reliability checks.

A secondary caregiver outcome, Support (15 items; alphas ranged from .76 to .84), was rated using the Indicator of Parent-Child Interaction (IPCI; Baggett, Carta, & Horn, 2009). This measure was selected because it was developed as an observational screening and monitoring tool for early intervention use in the home. Items were on a 4-point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, or often). Sample items include: “acceptance/warmth”; “descriptive language”; “follows child’s lead”. Caregiver support was rated by two coders and averaged across three activities: free play, book reading, and a distraction task. Inter-rater reliability was assessed on 34% of coded episodes. IPCI inter-rater agreement ranged from r = .80 to r = .84.

Commitment to child was rated from caregivers’ answers to interview questions from This Is My Baby (TIMB; Bates, 1998; Dozier & Lindhiem, 2006). Sample questions include: “How much would you miss (child) if he or she had to leave?”; “What do you want for (child) right now? In the future?” Indices of high commitment included: expression of the desire to parent the child as long as the child remains in care or is benefitting from care; evidence that the caregiver has allowed herself to become fully attached to the child without withholding feeling or putting up barriers to limit the extent of attachment; and evidence of a commitment of emotional or physical resources to support the child’s growth and development. Scores were assigned on a 5-point point scale with a higher score indicating higher commitment. Two coders were trained and reliability was monitored on 10% of data. Inter-rater agreement was r = .89.

Understanding of toddlers was measured by Raising a Baby (RAB; Kelly & Korfmacher, 2008), a measure of caregiver knowledge of infant and toddler social emotional needs and developmentally appropriate expectations. Caregivers rated RAB items on a 4-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) (16 items; Alphas ranged from .73 to .77). Sample items include “The best way to help a toddler through his tantrum is to ignore him”; “A toddler’s misbehavior is a sign they need help from his/her parent”.

Parenting stress associated with the perception of having a difficult child or a dysfunctional parent-child relationship was measured with the short form of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995). The PSI was administered as part of the structured interview. Two 4-point scales (strongly agree to strongly disagree) were used: Difficult Child (12 items) and Parent-child Dysfunction (11 items). Alphas ranged from .87 to .89. Sample items include: “My child smiles at me much less than I expected”; “Sometimes I feel my child doesn’t like me and doesn’t want to be close to me”.

Child outcomes

The primary child outcome of attachment security was measured with the Toddler Attachment Sort-45 (TAS45; Kirkland, Bimler, Drawneek, McKim, & Schölmerich, 2004), which was scored immediately after each research home visit. The TAS45 is a 45-item modified version of the Attachment Q-Sort (AQS; Waters, 1987), a gold standard attachment measure which has been extensively validated (van IJzendoorn, Vereijken, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Riksen-Walraven, 2004). The first version TAS45 was used in a large, nationally representative longitudinal sample. It used a five-pile sorting procedure and had excellent psychometrics for an overall security score comparable to that produced by the AQS (Andreassen, Fletcher, & Park, 2006; Bimler & Kirkland, 2004). We used a sorting technique that the developers of the TAS45 termed trilemmas in which the 45 descriptive statements are presented in specific sets of three. The three items in a sample trilemma are: “Child wants to be at the center of mother’s attention”; “Child is very independent”; “Child will go towards mother to give her toys, but does not touch nor look at her”. The observer decides which one of the three statements in the set is most like and which is least like the child’s behavior during the observation just completed. Each of the 45 statements appears in two trilemmas; there are 30 trilemmas in all. The scoring results in an overall security score. Two research visitors were trained to administer the TAS45 by the first author; in 16% of visits the TAS45 was coded by the two raters on-site. Inter-rater reliability was r = .92.

Engagement (9 items, alphas = .79–.82) was scored from the IPCI (Baggett et al., 2009) by two coders. Items such as “positive feedback”, “sustained engagement”, and “follow through (including turn-taking)” were coded on a 4-point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, or often). Reliability was assessed by the IPCI trainer on 34% of coded episodes across all three time points. IPCI inter-rater agreement ranged from r = .80 to r = .84.

Competence (11 items; Alphas = .69–.70) and Problem Behavior (31 items; Alphas =.77 = .79) were measured by the Brief Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA; Briggs-Gowan & Carter, 2002). Descriptions of positive social behaviors and problem behaviors in the last month were rated on a 3-point scale (not true/rarely; somewhat true/sometimes; very true/often).

At the six month follow-up, caregivers completed the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1 ½ –5 (CBC; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). The children were too young for caregivers to complete the CBC at previous assessments. Descriptions of behavior in the last two months were rated on a 3-point scale (not true; somewhat true/sometimes; very true/often). Four scales were used: Internalizing (36 items; Alpha = .80), Externalizing (24 items; Alpha = .90), Sleep problems (7 items; Alpha = .70), and Other Problems (32 items; Alpha = .70).

At baseline and again at the six month follow-up data collectors used 1 – 5 scales to rate the child’s behavior during administration of the Bayley-III Screening Test (Bayley, 2005) on seven of ten items from the Emotional Regulation factor and six of nine items from the Orientation/Engagement factor from the Bayley Behavior Rating Scales (BRS; Bayley 1993). We did not administer the Bayley at the post-intervention assessment because the interval from baseline was too brief. Alphas ranged from .79 to .87. Two research visitors were trained to rate the BRS scales; inter-rater reliability was assessed on 10% of visits. Inter-rater agreement ranged from r =.67 to r = .70.

Analysis

ANCOVA models were estimated to assess differences by experimental condition in caregiver and child variables at baseline and both follow-up time points. Covariates included whether the child experienced multiple removals from the birth home (differed between conditions), caregiver type, age of child (both associated with who was retained in the follow-up samples), and months between baseline and the given follow-up assessment (differed between conditions post-intervention). For post-intervention and 6-month follow-up, baseline score on the given measure (when available) was also included as a covariate. This approach gives an unbiased assessment of treatment effects in a randomized design (Van Breukelen, 2006). The maximum sample size for these models was 210 at baseline, 175 at post-intervention and 129 at 6-month follow-up; in addition, some measures had further missing data (< 5%) due to observational data being uncodable.

For measures available at all three time points, models of intervention effects on within-individual change were estimated using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). These models utilize data from all three time points and provide information on the timing of change. Two growth models were estimated for each outcome. The first model used two codings of time to estimate both change from baseline to post-intervention and change from post-intervention to 6-month follow-up. This model addressed (1) whether the intervention affected immediate within-individual change and (2) whether the differences increased or decreased in the subsequent 6-month period. The second model used just one coding of time and estimated intervention effects on linear change averaged across the three time points, thus addressing whether change began with exposure to the intervention and then continued to unfold in the post-intervention period. Codings of time were based on the number of months between dates of assessments. The models included intervention condition as an individual-level variable predicting effects of time. Caregiver type (represented by two dummy variables), age of child at enrollment, and whether there had been multiple removals were included as predictors of growth model intercepts (i.e., the expected value at baseline) and of the effects of time. The HLM models used data on all participants who had data from at least one time point, with the assumption of data being missing at random after adjusting for model covariates (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Results

A correlations matrix including experimental condition, covariates, and baseline measures is shown in Table 2. There were no baseline differences on any of the outcome measures. As expected, child security was significantly associated with higher caregiver sensitivity, support, and understanding of toddlers. In the child domain, child security was also significantly associated with higher engagement, competence and emotion regulation, and lower problem behavior.

Table 2.

Correlations among experimental condition, covariates, and baseline measures of study outcomes

| (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) EES = 0; PFR = 1 | −.01 | .19* | .01 | .09 | .01 | .09 | −.04 | −.09 | .10 | .09 | .07 | −.02 | .05 | .02 |

| (2) Age at baseline | .06 | .23* | .21* | .03 | .01 | .15* | .07 | −.08 | .24* | .20* | .21* | −.11 | .11 | |

| (3) Multiple removals | .07 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | −.08 | .01 | .01 | .09 | .08 | −.03 | −.03 | −.06 | ||

| (4) Sensitivity | .39* | .06 | .11 | −.08 | −.13* | .26* | .38* | .38* | −.03 | .16* | .15* | |||

| (5) Support | −.01 | .04 | .04 | −.06 | .38* | .77* | .17* | −.08 | .14* | .01 | ||||

| (6) Commitment | .03 | −.27* | −.22* | .07 | .01 | .23* | −.10 | .15* | .09 | |||||

| (7) Understanding toddlers | −.18* | −.37* | .17* | .09 | .16* | .00 | .21* | .03 | ||||||

| (8) Stress: difficult child | .72* | −.33* | .00 | −.35* | .65* | −.26* | −.18* | |||||||

| (9) Stress: parent child | −.36* | −.12* | −.41* | .40* | −.28* | −.19* | ||||||||

| (10) Security | .41* | .31* | −.30* | .49* | .13 | |||||||||

| (11) Engagement | .19* | −.07 | .28* | .21* | ||||||||||

| (12) Competence | −.26* | .19* | .14* | |||||||||||

| (13) Problem behavior | −.19* | −.12 | ||||||||||||

| (14) Emotion regulation | .41* | |||||||||||||

| (15) Orientation |

p < .05

Caregiver Outcomes

Results of the ANCOVA models for caregiver outcomes are presented in Table 3. At post-intervention, there was a significant intervention group difference on sensitivity, with a medium effect size. At the 6-month follow-up the group difference was not significant, although direction of the difference favored the PFR group with a small effect size. Estimates from HLM models corroborated these findings. At post-intervention, caregivers in the PFR condition scored higher on understanding of toddlers than caregivers in the EES condition, with a small effect size. The direction of difference and effect size was similar at the 6-month follow-up, although the difference was not significant. No other caregiver outcome was significant post-intervention, and no differences were found at the 6-month follow-up, although all effect sizes but one were in the predicted direction.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Caregiver Outcomes at Three Time Points by Experimental Condition; Test Statistic, Significance Level, and Effect Size for PFR at Post-Intervention and 6-month follow-up

| Baseline | Post-intervention | 6-month follow-up | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| EES (n=105) | PFR (n=105) | EES (n=89) | PFR (n=86) | F = | p = | d = | EES (n=70) | PFR (n=59) | F = | p = | d = | |

| Adj M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | |||||||

| Sensitivity | 12.19 (4.17) | 12.20 (3.71) | 11.76 (4.07) | 13.26 (3.70) | 5.22 | .024 | 0.41 | 13.64 (3.22) | 14.52 (3.15) | 2.02 | .158 | 0.29 |

| Support | 2.02 (0.48) | 2.12 (0.47) | 2.14 (0.41) | 2.18 (0.41) | 0.48 | .491 | 0.11 | 2.24 (0.41) | 2.31 (0.41) | 0.58 | .446 | 0.18 |

| Commitment | 4.12 (0.82) | 4.15 (0.88) | 4.21 (0.77) | 4.10 (0.71) | 0.86 | .354 | −0.17 | 4.34 (0.66) | 4.43 (0.59) | 0.67 | .414 | 0.16 |

| Understanding of toddlers | 49.95 (4.12) | 50.84 (4.83) | 50.92 (3.60) | 52.16 (4.98) | 4.21 | .042 | 0.36 | 50.97 (4.09) | 52.42 (4.91) | 3.55 | .062 | 0.39 |

| Stress-Difficult Child | 10.01 (6.00) | 9.82 (5.94) | 9.50 (5.54) | 10.45 (5.92) | 1.54 | .216 | 0.22 | 9.85 (6.13) | 9.57 (5.50) | 0.07 | .790 | −0.06 |

| Stress-Dysfunctional Interaction | 6.38 (4.90) | 5.42 (4.83) | 5.65 (4.58) | 6.13 (5.04) | 0.51 | .478 | 0.13 | 5.06 (4.72) | 5.69 (5.41) | 0.67 | .415 | 0.17 |

Notes: m = mean, adj. m = mean adjusted for ANCOVA model covariates, SD = standard deviation, d = effect size (diff in adjusted means/square root of mean square error).

ANCOVA models adjust for baseline score, age of child, whether multiple removals, caregiver type, and time between baseline and the given follow-up assessment.

Child Outcomes

Results for ANCOVA models of child outcomes are in Table 4. There were no significant differences between intervention and control children on security at either post-intervention or 6-month follow-up. Caregivers in the PFR condition reported greater child competence on the BITSEA at post-intervention with a medium effect size, but this result was no longer significant at 6-month follow-up, when the small effect size was negative (higher scores in the EES group). Finally, there was a marginally significant difference in caregiver report of child sleep problems at the 6-month follow-up, with a small effect size. PFR caregivers reported fewer sleep problems for their children than did EES caregivers.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Child Outcomes at Three Time Points by Experimental Condition; Test Statistic, Significance Level, and Effect Size for PFR at Post-Intervention and 6-month follow-up

| Baseline | Post-intervention | 6-month follow-up | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| EES (n=105) | PFR (n=105) | EES (n=89) | PFR (n=86) | F = | p = | d = | EES (n=70) | PFR (n=59) | F = | p = | d = | |

| Adj M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | Adj. M (SD) | |||||||

| Security | 0.46 (0.35) | 0.52 (0.32) | 0.54 (0.29) | 0.58 (0.30) | 0.68 | .410 | 0.16 | 0.55 (0.28) | 0.53 (0.37) | 0.12 | .736 | −0.13 |

| Engagement | 1.91 (0.58) | 2.02 (0.59) | 2.15 (0.49) | 2.08 (0.53) | 0.76 | .386 | −0.15 | 2.38 (0.50) | 2.29 (0.51) | 0.71 | .402 | −0.18 |

| Competence | 15.00. (3.43) | 15.40 (3.58) | 16.38 (3.19) | 17.35 (3.12) | 4.77 | .031 | 0.42 | 17.94 (2.77) | 17.53 (3.28) | 0.63 | .429 | −0.16 |

| Problem behavior | 11.28 (6.39) | 11.10 (6.21) | 10.72 (6.08) | 10.81 (6.45) | 0.01 | .924 | 0.02 | 9.09 (5.76) | 9.88 (5.74) | 0.62 | .434 | 0.16 |

| Internalizing problems | 7.55 (4.88) | 7.39 (5.85) | 0.02 | .879 | −0.03 | |||||||

| Externalizing problems | 13.94 (8.35) | 12.87 (8.55) | 0.42 | .520 | −0.13 | |||||||

| Sleep problems | 3.12 (2.88) | 2.27 (2.17) | 2.85 | .094 | −0.34 | |||||||

| Other problems | 9.99 (5.36) | 9.18 (6.13) | 0.51 | .475 | −0.14 | |||||||

| Emotional regulation | 3.60 (0.83) | 3.68 (0.75) | 4.01 (0.61) | 4.13 (0.69) | 1.02 | .314 | 0.20 | |||||

| Orientation | 3.93 (0.63) | 3.99 (0.68) | 4.38 (0.53) | 4.41 (0.49) | 0.13 | .723 | 0.06 | |||||

Notes: m = mean, adj. m = mean adjusted for ANCOVA model covariates, SD = standard deviation, d = effect size (diff in adjusted means/square root of mean square error).

ANCOVA models adjust for baseline score, age of child, whether multiple removals, caregiver type, and time between baseline and the given follow-up assessment.

Growth Models

Results for the HLM growth model for outcomes measured at all three assessments are reported in Table 5 and generally mirrored the results for the ANCOVA models. The effect of being in the PFR condition on monthly change in sensitivity scores between baseline and post-intervention follow-up was positive and significant, while the effect on change between post-intervention and 6-month follow-up was slightly negative and nonsignificant. The HLM model of linear change across all time points showed a nonsignificant effect of PFR on monthly change in sensitivity. Scores on understanding of toddlers increased for caregivers in the PFR condition compared to caregivers in the comparison condition from baseline to post-intervention, while the effect on change between post-intervention and 6-month follow-up was nonsignificant. The effect of PFR on change in understanding of toddlers across all time points was positive and marginally significant. The one slight divergence from the results for the ANCOVA models was for parent report of child competence where the HLM model of growth in this measure showed a nonsignificant PFR effect on change from baseline to post-intervention and a negative effect between post-intervention and 6-month follow-up, reflecting that scores in the comparison condition caught up with scores in the PFR condition. Change averaged across all three time points did not differ by condition.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for PFR effects on monthly change. Model 1 estimated effects on change for two time periods: baseline to post-intervention and post-intervention to 6-month follow-up. Model 2 estimated effect on change from baseline to 6-month follow-up.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PFR effect on change baseline to post-intervention | PFR effect on change post-intervention to 6-month follow-up | PFR effect on monthly change baseline to 6-month follow-up | |

|

| |||

| b (se) | b (se) | b (se) | |

| Sensitivity | .34* (.17) | −.08 (.07) | .06 (.06) |

| Support | .01 (.02) | −.01 (.01) | .02 (.01) |

| Commitment | .00 (.03) | .02 (.01) | .01 (.01) |

| Understanding of toddlers | .53** (.19) | −.01 (.07) | .13+ (.07) |

| Stress-Difficult Child | .19 (.23) | −.08 (.10) | .00 (.09) |

| Stress-Dysfunctional Interaction | −.05 (.20) | .05 (.08) | .07 (.07) |

| Security | .00 (.01) | .01 (.01) | .00 (.01) |

| Engagement | −.02 (.02) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) |

| Competence | .10 (.12) | −.15** (.05) | −.07 (.05) |

| Problem behavior | .05 (.27) | .03 (.10) | .03 (.09) |

Notes: b = effect of PFR on monthly rate of change, se = standard error,

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10.

Model 1 used two codings of time to estimate both change from baseline to post-intervention and change from post-intervention to 6-month follow-up. Model 2 used one coding of time and estimated intervention effects on linear change across the three time points.

Equations for the Model 1:

Coded 0 for baseline and months between baseline and post-intervention for both post-intervention and 6-month follow-up; if post-intervention time point missing, coded as 2.9 for EES condition and 4.2 for PFR condition.

Coded 0 for baseline and post-intervention time point and months since baseline for 6-month follow-up

Equations for the equations Model 2:

Discussion

PFR: An Attachment-Based Intervention for Caregivers of Toddlers in Foster Care

The need to address the unique developmental vulnerability and primary attachment relationship needs of infants and toddlers in child welfare has been an increasing focus in recent years (Jones Harden, 2007; Stahmer et al., 2005; Zeanah et al., 2011). This study subjected a respected infant mental health training program, Promoting First Relationships (PFR), to a rigorous randomized control trial evaluation. Our aim was to improve caregiver sensitivity and caregiver understanding that difficult toddler behavior reflects unmet social emotional needs, so that caregivers could sensitively respond in ways that would help children become more secure and more behaviorally and emotionally regulated. Community-based providers with no previous infant mental health specialization were trained to deliver PFR to parents and caregivers of toddlers in child welfare dependency. Results indicate that the brief, 10-week PFR program could improve caregiver sensitivity and understanding of toddlers. Modest effect sizes for these caregiver outcomes, though not statistically significant for sensitivity and only marginally so for understanding of toddlers, persisted to the 6-month follow-up. Results from an ANCOVA model indicated differences in perceptions of child competence, with caregivers in the PFR perceiving more competencies, but this was not supported by a growth model of change. It would have been expected that competencies would continue to develop at a higher rate for children in the PFR condition, but the growth model of linear change across all three time points did not show this, and the piecewise model showed a significant increase in reported competences post-intervention that was greater in the EES condition.

Effect sizes on improved caregiver sensitivity in this study are consistent with moderate effect sizes shown in randomized trials of other brief attachment-based interventions. For example, the Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. (2003) meta-analysis, reported a combined effects size of d = 0.33 for a core set of 51 randomized studies (n = 6,282). Eight of those studies (n = 1,707) used an older version of our measure of sensitivity, the NCATS total score, for which Bakermans-Kranenburg and colleagues reported a combined effect size of d = 0.25.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find that PFR improved child security. We expected PFR children to show growth in attachment security greater than EES children with rates of improvement maintained across the three assessment time points, resulting in higher scores at the 6-month follow up. In the Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. (2003) meta-analysis, attachment interventions that specifically focused on improving caregiver sensitivity did have an overall significant effect on attachment security (d = .39). Although the effect sizes for our sensitivity measure were comparable, the effect sizes on attachment were not. Infants older than 12 months less readily seek closeness to new attachment figures (Stovall-McClough & Dozier, 2004) and, additionally, toddlers with maltreatment and foster care histories bring behaviors and expectations to new attachment relationships that profoundly affect their trajectory (Lieberman, 2003). The mean and median infant age in this study was 18 months; 88% of the sample was older than one year. Despite improving caregiver sensitivity, PFR may be too brief or too late to result in changes in attachment security or engagement with the caregiver when children have this background. However, improving caregiver sensitivity may benefit child development in other domains not measured in this study, such as problem solving, peer relations, achievement, and social competence (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2003, 2004; Raikes & Thompson, 2008).

Children in the PFR condition did show a marginally significant decline in sleep problems, as reported by caregivers, with a modest effect size, a promising finding that warrants further study. Sleep is an essential self-regulatory activity (Degangi et al., 2000). Sleep problems in early childhood are implicated in several child and adolescent psychopathologies (Reid, Hong, & Wade, 2009). Tininenko, Fisher, Bruce, and Pears (2010) found preschool children in therapeutic foster care had better sleep quality than children in regular foster care. Sleep hygiene was not a focus of PFR, but may be a consequence of an increase in caregiver sensitivity, consistency, and routines. Overall, however, the evidence from this study for PFR’s efficacy with the population of infants and toddlers in child welfare dependency is limited.

Other intervention studies with child welfare populations (Bernard et al., 2012; Dozier et al., 2009; Fisher & Kim, 2007; Moss et al., 2011) have shown intervention effects on child attachment security using the gold standard brief separation and reunion procedure, the Strange Situation (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters & Wall, 1978). Our measure of child attachment security, the TAS45, has promising features associated with another gold standard (according to van IJzendoorn et al., 2004), the Attachment Q-Sort (AQS; Waters, 1987). The five-pile version has been shown to be reliable and valid (Andreassen et al., 2006). We think the trilemma version we used did not permit observers enough nuance in their ratings. As an example of the kind of results that limit our confidence in the measure, the mean security score in our sample at baseline was .48 compared to .32 for normative samples or .21 for clinical samples (van IJzendoorn et al., 2004). If the security scores on the TAS45 and AQS are comparable, as intended (Andreassen et al., 2006) by the developers of the TAS45, we would not expect that children in this sample would be more secure than children who have never been maltreated or separated from attachment figures.

Of the two gold standards, only the Strange Situation detects attachment disorganization, which is a critical target of intervention for children in child welfare (Bernard et al., 2012). It is important to be able to detect indices of disorganized attachment or of inhibited and disinhibited attachment disorder that are more likely to be exhibited by children with a history of maltreatment (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van IJzendoorn, 2010). Attachment disorganization is considered to be orthogonal to attachment security (van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999), that is, children can have a primary secure or insecure attachment strategy and simultaneously show behavior indicative of disorganization, because in addition to insensitivity, atypical caregiver behaviors such as behavior that is at times frightening or dissociated, predict disorganization (Moran, Forbes, Evans, Tarabulsy, & Madigan, 2008). As an example of this complexity for toddlers in foster care, Oosterman and Schuengel (2008) found an association between foster parent sensitivity and foster children’s attachment security as measured by the AQS only when controlling for symptoms of inhibited and disinhibited attachment disorder; the bivariate association between sensitivity and attachment security, r = .18, was not significant. For all these reasons, the Strange Situation remains the most desirable measure for detecting intervention effects; we recommend the TAS45 five-pile sort in future studies if the gold standard Strange Situation or AQS are not feasible.

Study Strengths and Weaknesses

The strengths of this study include its ‘real world’ use of community providers to deliver the interventions, use of observational outcome measures in addition to caregiver report, and the choice of PFR, a manualized attachment-based training program that has had wide appeal among service providers and administrators in Washington state. This project, by design, was consistent with Lee, Aos and Miller’s (2008) assertion that the most convincing evidence for effective interventions that states are willing to fund are those programs that have been evaluated in “real world” settings. We assessed community providers’ fidelity PFR intervention approaches, and four out of five were able to consistently deliver the model with high fidelity. These strengths support the study’s relevance to real world child welfare practice.

A weakness of the study is that this real world approach made it vulnerable to exogenous factors, such as the heterogeneity in caregiver types and varied effectiveness of community providers. The most important threat to the internal validity of the study came from placement changes after enrollment that were dictated by child welfare practices. These placement changes disrupted over a third of the caregiver-child dyads that enrolled in the study and reduced the sample for assessing differences at the 6-month follow-up to 129, only 61% of the original sample. This resulted in a reduction in power which decreased the ability to detect differences between the PFR and control conditions. The study was designed to have sufficient power to detect small to medium effect sizes. We expected 85% retention of the sample at the post-intervention time point, which yields power of .80 to detect an effect sized of d = .42 with an alpha of p < .05. The actual retention of dyads that did not experience a caregiver change by post-intervention was 83%. We anticipated that numerous caregiver changes would occur before the 6-month follow-up, although not as many as in fact occurred. The sample of 129 intact dyads yields .80 power to detect an effect size of d = .50 with an alpha of p < .05.

Lack of power further limits our ability to investigate the potentially important role of caregiver type (birth parent, kin provider, or foster parent) in change in child outcomes or in the effectiveness of the PFR intervention. Caregiver type as a covariate in the ANCOVA and HLM models had few statistically significant effects. For example, out of 24 ANCOVA models caregiver type had a significant main effect in only two. These main effects reflected the fact that foster caregivers reported fewer child competencies at post-intervention and reported less commitment at the 6-month follow-up. Secondary analyses that examined caregiver type by experimental condition interactions also revealed only two statistically significant results for the 24 ANCOVA models. One interaction pointed to foster parents in the PFR condition reporting more problem behaviors for their children at the 6-month follow-up than foster parents in the EES condition, while PFR versus EES differences were in the opposite direction among birth parents and kin caregivers. Another interaction pointed to lower observed behavioral support among PFR kin caregivers than EES kin caregivers at the 6-month follow-up, while differences among birth parents and foster caregivers were in the opposite direction, albeit nonsignificant. Given the lack of power and inconsistent direction of results, we feel that no strong inferences can be made about differential effectiveness of the PFR intervention by caregiver type.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The results from this study, by itself, provide some support that PFR improves the caregiving experienced by maltreated toddlers in child welfare dependency with a history of relationship disruptions, but there is no indication that PFR can boost attachment security or self-regulation in this population. Perhaps findings from future trials, when combined with results from this trial, will provide a clearer picture regarding both caregiver and child outcomes. A consideration of the factors that might be associated with the modest results for PFR in this study lead policy and practice recommendations regarding programs for vulnerable infants and toddlers in foster care.

First, given the rapid development of very young children and our finding that initial effects weakened over time, in the future stakeholders may decide that a program with planned ‘boosters’ is necessary for sustained impacts in this population. Second, given the developmental risks experienced by this population, a potential point of entry for delivering infant mental health services to prevent or ameliorate attachment relationship and regulatory problems for infants and toddlers in child welfare may be through early childhood intervention (ECI) programs funded under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA of 1997). Since 2003, an amendment to the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) has required developmental screening of children under three in child welfare. Socioemotional and regulatory problems, as well as motor, cognitive, and language delays, qualify for ECI services. Early childhood interventionists are willing to serve the child welfare population but they may not have the skills to effectively intervene at the level of the relationship (Herman-Smith, 2011). PFR has been training ECI providers from a variety of disciplines in this skill set for many years (Kelly, Zuckerman, & Rosenblatt, 2008).

Early in this study we detected greater attrition in the PFR intervention compared to the EES group, possibly due to the greater time commitment required for PFR when families also had many appointments to keep for their children. We improved retention over the course of the study by working with the community PFR providers to be more persistent and tenacious when caregivers cancelled or were not home, and to be more flexible in their scheduling of visits to meet the needs of families. Although this sort of flexibility in service provision is central to infant mental health practice, it was not initially the case for these community providers.

There is also a need to increase understanding by child welfare workers about infant/toddler development and the importance of stability and consistency of attachment figures, and as well as to research the impact of placement quality and stability, and the level and type of parent-child visitation, on children’s developmental trajectories (Jones Harden & Klein, 2011). Although in this study PFR was an intervention for caregivers of children in the child welfare system, we believe that training child welfare workers in the PFR core curriculum and consultation strategies would enable them to make developmentally-informed, relationship-based decisions that promote the well-being of infants and toddlers.

Relatedly, we note that there was no voluntary attrition in over three years among the five community mental health providers who were trained in PFR and received weekly reflective consultation for the duration of the project. In contrast, two of three EES providers, who did not receive intensive weekly reflective consultation, left during the course of the project. Reflective consultation is a core tenet of infant mental (Gilkerson & Kopel, 2005) and, according to a post-study evaluation, one reason the PFR providers in this study stayed with the project. Providers also liked the opportunity to improve their skills and receive strengths-based mentoring, which, after all, is what we wanted them to provide to families. We believe the same opportunity should be available to child welfare workers, who experience considerable stress in the course of their work with vulnerable children and families.

Conclusions

With strong, sustained support from a regional child welfare office and the committed participation of community mental health agencies and their designated providers, we conducted the first randomized control trial of Promoting First Relationships, a brief, strength-based, attachment-theory based home visiting program that utilizes reflective consultation strategies and video feedback, with caregivers of maltreated toddlers adjusting to new primary caregivers in new homes. We found modest improvements in caregiver sensitivity and attitudes but no observable PFR effects on child functioning. The study demonstrates that a rigorous evaluation can be conducted in a real-world setting with a vulnerable, mobile population. The results of this study were not as strong as earlier results of quasi-experimental evaluations of PFR, but the caregiver outcomes were aligned with published results from similar clinical trials with less vulnerable populations. Additional studies are in progress that will add to our knowledge of PFR’s effectiveness as an intervention for caregivers and their children. It is important for policy makers to consider both quality and quantity of evidence when allocating resources for ‘evidence-based’ programs for their communities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 MH077329 from the National Institute of Mental Health. This work was also facilitated by grant P30 HD02274 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank Maureen Marcenko for critiquing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Susan J. Spieker, Family & Child Nursing, University of Washington

Monica L. Oxford, Family & Child Nursing, University of Washington

Jean F. Kelly, Family & Child Nursing, University of Washington

Elizabeth M. Nelson, Family & Child Nursing, University of Washington

Charles B. Fleming, Fleming, School of Social Work, University of Washington

References

- Abidin RA. Parenting Stress Index: Short Form (PSI-SF) Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1 1/2–5. ASEBA, University of Vermont; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Administration for Children and Families. Child Maltreatment 2000. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm00.

- Administration for Children and Families. Child Maltreatment 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm10/index.htm.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C, Fletcher P, Park J. Toddler’s Security of Attachment Status. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) Psychometric report for the 2-year data collection. 2006 Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED497762&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED497762.

- Baggett KM, Carta JJ, Horn EM. Indicator of Parent-Child Interaction (IPCI) User’s Manual. Lawrence, KA: Special Education, University of Kansas; 2009. http://www.igdi.ku.edu/training/IPCI_training/IPCI_admin_instructions.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(2):195–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn M, Juffer F. Disorganized infant attachment and preventive interventions: A review and meta-analysis. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26(3):191–216. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard KE. What the Teaching Scale measures. In: Sumner GS, Spietz A, editors. NCAST: Caregiver/parent-child interaction teaching manual. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, NCAST Publications; 1994. http://www.ncast.org/index.cfm?category=2. [Google Scholar]

- Bates BC. “This Is My Baby” coding manual. Newark, DE: University of Delaware; 1998. Retrieved from http://icp.psych.udel.edu/PDF/TIMB_coding.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2005. (Bayley-III) Screening Test. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis-Morrarty E, Lindheiem O, Carlson E. Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Development. 2012;83(2):622–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimler D, Kirkland J. Unpublished manuscript. Massey University; New Zealand: 2004. The ABC(D) of the TAS45 (Toddler Attachment Set - 45): A lay figure’s guide to analysis and interpretation of TAS45 data. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Vol 1:Attachment. 2. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969/1982. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan M, Carter AS. Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) Manual, version 2.0. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Hanson R, Saunders BE, Nichols T, Barnett D, Zeanah C, Miller-Perrin C. Report of the APSAC task force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11(1):76–89. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283699. 11/1/76 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: a series of meta-analyses. Development & Psychopathology. 2010;22(1):87–108. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990289. S0954579409990289 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff MS, van IJzendoorn MH. Sensitivity and attachment: a meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68(4):571–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degangi GA, Breinbauer C, Doussard RJ, Porges S, Greenspan S. Prediction of childhood problems at three years in children experiencing disorders of regulation during infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2000;21(3):156–175. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(200007)21:3<156::AID-IMHJ2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Higley E, Albus KE, Nutter A. Intervening with foster infants’ caregivers: Targeting three critical needs. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23(5):541–554. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10032/. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M Infant-Caregiver Lab. Attachment and biobehavioral catch-up (ABC) Baltimore: University of Delaware; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lindheiem O, Lewis E, Bick J, Bernard K, Peloso E. Effects of a foster parent training program on young children’s attachment behaviors: Preliminary evidence from a randomized clinical trial. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2009;26(4):321–332. doi: 10.1007/s10560-009-0165-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lindhiem O. This is my child: Differences among foster parents in commitment to their young children. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11(4):338–45. doi: 10.1177/1077559506291263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Kim HK. Intervention effects on foster preschoolers’ attachment-related behaviors from a randomized trial. Prevention Science. 2007;8(2):161–170. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkerson L, Kopel CC. Relationship-based systems change: Illinois’ model for promoting social-emotional development in Part C early intervention. Infant & Young Children. 2005;18(4):349–365. [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger JF, Kelly K, Slade A. Maternal reflective functioning, mother-infant affective communication, and infant attachment: exploring the link between mental states and observed caregiving behavior in the intergenerational transmission of attachment. Attachment & Human Development. 2005;7(3):299–311. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245963. T16736R7230257Q4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Smith R. Early childhood interventionists’ perspectives on serving maltreated infants and toddlers. Children & Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1419–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Harden B. Infants in the child welfare system: A developmental perspective on policy and practice. Washington, DC: Zero to Three; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Harden B, Klein S. Infants/toddlers in child welfare: What have we learned and where do we go from here? Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1464–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn M. Methods of the video-feedback programs to promote positive parenting alone, with sensitive discipline, and with representational attachment discussions. In: Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn M, editors. Promoting positive parenting: An attachment-based intervention. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF. Final report: A relationship-focused approach to family stabilization. Seattle, WA: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Pacific Northwest Program/Community Grants; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Buehlman K, Caldwell K. Training and early intervention to promote quality parent-child interaction in homeless families. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2000;20(3):174–185. http://www.sagepub.com/journals/Journal201884. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Sandoval D, Zuckerman TG, Buehlman K. Promoting First Relationships: A Program for Service Providers to Help Parents and Other Caregivers Nurture Young Children’s Social and Emotional Development. 2. Seattle, WA: NCAST Programs; 2008. http://www.ncast.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=category.display&category_id=2I. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Korfmacher J. Unpublished manuscript. University of Washington; 2008. Raising A Baby. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Zuckerman TG, Rosenblatt S. Promoting First Relationships: A relationship-focused early intervention approach. Infants& Young Children. 2008;4(21):285–295. doi: 10.1097/01.IYC.0000336541.37379.0e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland J, Bimler D, Drawneek A, McKim M, Schölmerich A. An alternative approach for the analyses and interpretation of attachment sort items. Early Child Development and Care. 2004;174(7–8):701–719. doi: 10.1080/0300443042000187185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klee L, Kronstadt D, Zlotnick C. Foster care’s youngest: A preliminary report. Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(2):290–299. doi: 10.1037/h0080232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Aos S, Miller M. Evidence-based programs to prevent children from entering and remaining in the child welfare system: Benefits and costs for Washington. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute of Public Policy; 2008. Document No. 08-07-3901. http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/pub.asp?docid=08-07-3901. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF. The treatment of attachment disorder in infancy and early childhood: Reflections from clinical intervention with later-adopted foster care children. Attachment & Human Development. 2003;5(3):279–282. doi: 10.1080/14616730310001596133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meins E, Fernyhough C, Fradley E, Tuckey M. Rethinking maternal sensitivity: mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2001;42(5):637–648. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran G, Forbes L, Evans E, Tarabulsy GM, Madigan S. Both maternal sensitivity and atypical maternal behavior independently predict attachment security and disorganization in adolescent mother–infant relationships. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31(2):321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss E, Dubois-Comtois K, Cyr C, Tarabulsy GM, St-Laurent D, Bernier A. Efficacy of a home-visiting intervention aimed at improving maternal sensitivity, child attachment, and behavioral outcomes for maltreated children: a randomized control trial. Development & Psychopathology. 2011;23(1):195–210. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000738. S0954579410000738 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Families matter--even for kids in child care. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003;24(1):58–62. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Fathers’ and mothers’ parenting behavior and beliefs as predictors of children’s social adjustment in the transition to school. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(4):628–638. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.628. 2004-21520-010 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]