SUMMARY

Malignant external otitis (MEO) is a rare infection of the temporal bone primarily affecting elderly patients and diabetics or immunocompromised individuals, which may have dismal prognosis if treatment is not prompt and adequate. Almost 95% of MEO cases reported in the literature are attributed to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and this pathogen is isolated from aural drainage in > 90% of cases. However, in recent years fungal and polymicrobial temporal bone infections have been reported with increasing frequency. The aim of this paper is to discuss a possible pitfall in MEO treatment using an unusual clinical case. In this patient, bacteriological data positive for Pseudomonas delayed correct diagnosis of Aspergillus infection, which was obtained after surgical debridement and biopsy of the infra-temporal space.

KEY WORDS: Necrotizing otitis externa, Diagnosis and prognosis, Aspergillus

RIASSUNTO

L'otite esterna maligna (MEO) è una rara infezione dell'osso temporale che colpisce soprattutto pazienti anziani e diabetici o individui immunocompromessi, che può avere prognosi infausta se il trattamento non è rapido e adeguato. Quasi il 95% dei casi di MEO riportati in letteratura sono attribuiti a Pseudomonas aeruginosa e questo patogeno è isolato dal materiale di drenaggio auricolare in più del 90% dei casi. Tuttavia negli ultimi anni infezioni polimicrobiche e micotiche dell'osso temporale sono sempre più frequenti. Scopo di questo lavoro è discutere del rischio di fallimento terapeutico nell'otite esterna maligna attraverso l'illustrazione di un caso clinico in cui il tampone auricolare positivo per Pseudomonas ha ritardato la diagnosi della infezione da Aspergillus, ottenuta dopo un debridement chirurgico dello spazio infra-temporale.

Introduction

Malignant external otitis (MEO) is a rare infection of the temporal bone primarily affecting elderly patients and diabetics or immunocompromised individuals, which may have dismal prognosis if treatment is not prompt and adequate. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is responsible for almost all cases, although a few cases may be due to other microorganisms (Aspergillus species, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella oxytoca and others) 1-3.

The disease manifests as a painful inflammation of the external ear canal, associated with purulent otorrhea and granulation polyps. Otalgia is the presenting symptom in 75% of cases; it is intense, particularly during the night, and associated with a severe temporal or occipital headache. The purulent otorrhea appears with a frequency ranging from 50 to 80% and varies from a moist and modest secretion to a greenish malodorous and abundant exudate. Histologically, granulation tissue is characterized by non-specific inflammation with inflammatory cell infiltration and hyperplasia of squamous epithelium.

The progression of the disease has been divided into 3 clinical stages as shown in Table I 4. In the third stage, the infection reaches the intracranial structures, neck spaces and large blood vessels. This stage is always associated with poor prognosis. The most frequent causes of death are meningitis, large vessel septic thrombophlebitis or rupture, septicaemia, pneumonia caused by inhalation for vagal paralysis and cerebrovascular accident 5 6.

Table I.

Clinical-radiological stages of malignant external otitis.

| Stage I: infection of the external auditory canal and adjacent soft tissues with severe pain, with or without facial nerve paralysis. |

| Stage II: extension of infection with osteitis of skull base and temporal bone, or multiple cranial nerve neuropathies. |

| Stage III: intracranial extension with meningitis, epidural empyema, subdural empyema or brain abscess. |

The aim of this paper is to discuss a possible pitfall in MEO treatment using an unusual clinical case. In this patient, the bacteriological data positive for Pseudomonas delayed correct diagnosis of Aspergillus infection, which was obtained after surgical debridement and biopsy of the infratemporal space.

Clinical case

Between 1992 and 2009, 8 patients affected by MEO have been treated at our Department. The causative pathogen was Pseudomonas aeruginosa in all cases except in the one presented, where Pseudomonas was associated with Aspergillus fumigatus.

In 2006, a 69-year-old insulin-dependent male with diabetes presented to our clinic complaining of otalgia and otorrhoea lasting for 2 months, despite repeated treatment with systemic antibiotic and local antiseptic irrigation. On examination, the right ear canal was full of purulent secretion, oedematous and occupied by extensive granulation tissue, the tympanic membrane was hyperaemic and thickened. Ear discharge was cultured for bacteria and mycosis with isolation of P. aeruginosa. The patient had no fever and blood cultures were not performed. Blood examination demonstrated ESR = 142 mm; CRP = 116 mg/l; WBC = 12.45 × 109/l. MR I demonstrated a diffuse inflammation of temporal bone cavities, while CT excluded bone erosions. He was treated with aural toilet on a regular basis, ciprofloxacin 750 mg (BID) and control of diabetes, but two weeks later, when still on treatment, he developed right facial paresis. The ear swab was repeated and was positive for P. aeruginosa. A meatoplasty with mastoidotympanoplasty to remove the infected and necrotic tissue was carried out. Moreover, meropenem was started at a dosage of 2 gm (TID) and continued for 2 weeks. Although a control ear swab was negative for bacterial infection, the previous treatment with ciprofloxacin was continued. Four months later the patient was still on treatment, when he manifested a paralyses of glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. MR I demonstrated pathologic tissue occupying the right cranial base, widening the jugular foramen, and the retropharyngeal space reaching the omolateral clivus, while CT scans disclosed bone erosion extending beyond the previous surgical mastoidectomy (Figs. 1, 2). The patient underwent skull base surgical debridement and a specimen of infratemporal tissue demonstrated non-specific inflammation, while bacterial examination and culture grew A. fumigatus. Voriconazole was administered at a dosage of 400 mg i.v. twice for the first day, followed by 200 mg i.v. (BID). After one month of antifungal therapy, there was significant clinical improvement in general conditions, control of diabetes and reduction of otalgia and headache. Inflammation indices were reduced as follows: ESR = 15 mm; CRP = 16 mg/l; WBC = 6.25 × 109/l. Furthermore, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve function became normal. The treatment was maintained for 3 months: at this time, complete normalization by MR I was demonstrated, together with resolution of clinical signs and normalization of biochemical indexes of inflammation. Follow-up was carried out with regular MR I and blood examination. After 4 years of follow-up, there are no signs of disease although facial paresis persists.

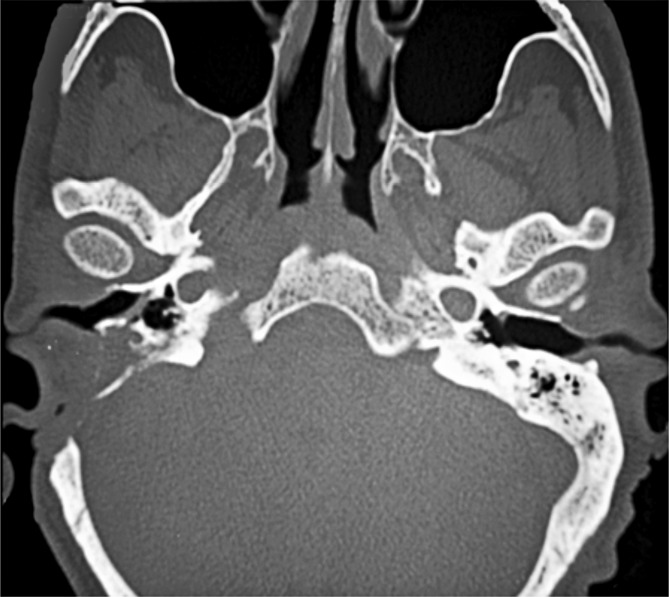

Fig. 1.

Axial CT showing soft tissue involvement of the right external and the middle ear with bone erosion. Enlargement of the right foramen lacerum and condyloid canal, as well the facial nerve canal, can be observed.

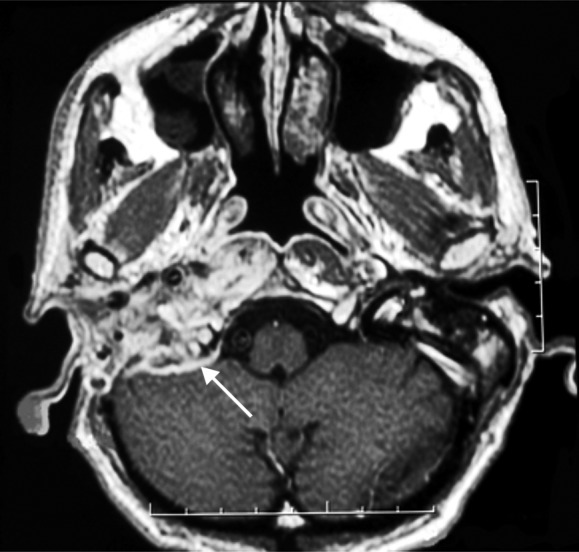

Fig. 2.

T1 weighted with contrast magnetic resonance, axial section. Pathological tissue on T1 weighted images with contrast enhancement involves the neotympanic cavity, the lateral parapharyngeal space, the right posterior foramen lacerum, as well as the condyloid canal. It also extends posteriorly involving the right cerebellum (arrow).

Discussion

Malignant external otitis is an insidious disease with frequently delayed diagnosis, so that patients are often treated for a trivial external otitis. Almost 95% of MEO cases reported in the literature are attributed to P. aeruginosa, and this pathogen is isolated from aural drainage in > 90% of cases 1 3. However, in recent years fungal and polymicrobial temporal bone infections have been reported with increasing frequency 1-3. In fact, P. aeruginosa is frequently a saprophyte in the external auditory meatus and sometimes other associated bacteria or fungi can have an important or predominant role in the aetiology of MEO, particularly in immunocompromised patients, such as in AIDS, where Pseudomonas is not the predominant pathologic organism 1 7.

Although fungal infections are generally more invasive than bacterial disease, all the other clinical and radiological features, including survival, are similar 2 3 8. Thus, even the isolation of Pseudomonas from aural discharge may be not sufficient or specific enough to distinguish between the two forms. As emphasized by Leonetti and Marzo 9 patients are either referred with previous cultures and biopsy findings or are extremely tender on external auditory meatus manipulation; general anaesthesia is required to obtain an adequate biopsy. For these reasons, it is tempting to rely either on previous findings or on bacteriologic data to direct therapy. As a consequence, Pseudomonas isolation may delay correct diagnosis of fungal infection 10.

On the other hand, Aspergillus is also frequently isolated from external auditory canal smears and diagnosis of fungal MEO should be based on histopathologic confirmation on deep tissue biopsy or isolation from blood cultures or fistula exudates 10. No diagnostic conclusions can be drawn from single positive cultures from the external auditory canal or from middle ears with chronic perforations.

The Aspergillus identified in our patient was isolated on deep tissue specimens obtained at surgery: we assume they were neither contaminated or secondary to prior antibiotic therapy. This peculiar case of MEO underlies the importance of performing repeated biopsies and culture to identify microorganisms, which can be different or associated with the most common causative (i.e. P. aeruginosa). Often, multiple histologic sections are necessary for identifying fungi or other particular organisms.

Blood tests are generally non-specific except for a constant elevation of inflammatory indices: an elevated ESR and CRP were present in 100% of patients and often reached values > 100. Conversely, leukocytosis is rare. ESR and CRP are also indicators of disease activity and are useful for monitoring the course of therapy and effectiveness of antibiotic treatment. Recently, two different markers, galactomannan and β-glucan have demonstrated their value in diagnosis and monitoring the course of ininvasive aspergillosis during therapy 11. Unfortunately, false positivity may be related to antibiotic treatment 12, while false negativity may be observed in immunocompromised patients. In the past, MRI has been used in association with other imaging modes for diagnosis and follow-up of MEO (i.e. Tc-99MDP bone scanning, Ga-76 citrate scanning and gallium-67 SPECT). However, MRI has many advantages over other modalities and can be used as the sole imaging modality 13. In our case, a temporal bone CT carried out after the clinical worsening of disease demonstrated bone erosion that was not present initially. Moreover, MRI was repeated several times during treatment and follow-up with good monitoring of disease evolution.

When MEO is suspected, patients have been generally started on empirical antipseudomonal therapy due to the high incidence of this causative pathogen. Ciprofloxacin is still the treatment of choice, although increasing resistance is observed among Pseudomonas strains. In our district, 9.5% of Pseudomonas strains isolated from ear swabs are resistant to ciprofloxacin. Thus, we still use this antibiotic empirically in external otitis when Pseudomonas aetiology is suspected and microbiological data are lacking. Nevertheless, the incidence of antibiotic resistance should be regularly monitored in each hospital district. Antibiotic therapy is associated with regular external ear canal cleaning in micro-otoscopy and medicated washes. There is no role for topical antibiotics, even quinolones, in the treatment of MEO. Instillation of antipseudomonal topical agents only increases the difficulty of isolating the pathogenic organism from the ear canal.

On the other hand, topical antibiotics are generally recommended for bacterial external otitis, but it should be considered that the incidence of mycotic forms has significantly risen since the end of 1990s, when the use of quinolone ear drops became common clinical practice 14.

If a fungus is the causative organism, prolonged treatment (> 12 weeks) with amphotericin B is indicated. A liposomal amphotericin B preparation is recommended to keep to a minimum the incidence of nephrotoxicity in diabetic patients. More recently, voriconazole has demonstrated high efficacy in MEO caused by Aspergillus species 15. Hyperbaric oxygen has been used on occasion with mixed results, and may be considered as adjuvant treatment for refractory cases although its efficacy remains unproven 4 16.

The decision between conservative antimicrobial therapy and surgical treatment can present a therapeutic challenge in the management of these life-threatening infections, especially in patients with existing immunodeficiency and illness 17. Although bone sequestra and abscess are treated surgically, the need for more aggressive treatment is debatable. Some authors suggest that prompt surgical debridement consisting of radical mastoidectomy is indicated in the majority of cases, particularly in fungal diseases, which are more invasive with respect to bacterial pathogens 15 18-20.

In the series reported by Hamzani 2, extensive surgery was carried out in 78% of fungal MEO vs. 18% in bacterial ones. However, other authors stress the fact that extensive surgery may be even counterproductive because of the risk of exposing healthy bone to infection 3 21. Unfortunately, there are neither guidelines nor definite recommendations with regard to the surgical treatment of the different forms of MEO 22.

In our case, we carried out extensive infratemporal debridment which permitted a correct causative diagnosis through histological and bacteriological examination of tissues. Nevertheless, it remains questionable whether a more limited deep tissues biopsy followed by antifungal treatment would have been sufficient to resolve the disease.

In conclusion, all cases of otitis externa by Pseudomonas in elderly diabetic or immunocompromised patients should be initially treated as potential forms of MEO. The course of MEO is initially subtle, and the disease may have poor prognosis if not properly treated. Nevertheless, no diagnostic conclusions can be drawn from single positive cultures from the external auditory canal. In fact, colonization with Pseudomonas, both in chronic otitis media and in superficial external otitis is probably common, and thus mycosis should be suspected whenever clinical signs of infection do not improve despite adequate anti-Pseudomonas treatment 2 5 23. In these cases, deep tissue biopsy or isolation from blood cultures is required for histopathological confirmation.

References

- 1.Grandis JR, Branstetter BF, Yu VL. The changing face of malignant external otitis: clinical, radiological, and anatomic correlations. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamzany Y, Soudry E, Preis M, et al. Fungal malignant external otitis. J Infect. 2011;62:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carfrae MJ, Kesser BW. Malignant otitis externa. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41:537–549. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis JC, Gates GA, Lerner C, et al. Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen in malignant external otitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:89–93. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880010093022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CN, Chen YS, Yeh TH, et al. Outcomes of malignant external otitis: survival vs. mortality. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:89–94. doi: 10.3109/00016480902971247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soudry E, Hamzany Y, Preis M, et al. Malignant external otitis: analysis of severe cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:758–762. doi: 10.1177/0194599810396132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ress BD, Luntz M, Telischi FF, et al. Necrotizing external otitis in patients with AIDS. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:456–460. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrow HN, Levenson MJ. Necrotizing "malignant " external otitis caused by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:94–96. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880010098023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonetti JP, Marzo SJ. Invasive fungal and bacterial infections of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1503–1507. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200309000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez-Berriotxoa A, Montejo M, Aguirrebengoa K, et al. Otomastoiditis caused by Aspergillus in AIDS. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1997;15:200–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mokaddas E, Burhamah MH, Ahmad S, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: value of DNA, galactomannan and (1->3)-beta-D-glucan detection in serum samples as an adjunct to diagnosis. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:1519–1523. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.023630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boonsarngsuk V, Niyompattama A, Teosirimongkol C, et al. False-positive serum and bronchoalveolar lavage Aspergillus galactomannan assays caused by different antibiotics. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:461–488. doi: 10.3109/00365541003602064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail H, Hellier WP, Batty V. Use of magnetic resonance imaging as the primary imaging modality in the diagnosis and follow-up of malignant external otitis. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:576–579. doi: 10.1258/0022215041615100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin TJ, Kerschner JE, Flanary VA. Fungal causes of otitis externa and tympanostomy tube otorrhea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1503–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parize P, Chandesris MO, Lanternier F, et al. Antifungal therapy of Aspergillus invasive otitis externa: efficacy of voriconazole and review. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1048–1053. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01220-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips JS, Jones SEM. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjuvant treatment for malignant otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD004617–CD004617. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004617.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, Lalwani AK, House JW, et al. Aspergillus mastoiditis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Otol. 1999;20:561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amonoo-Kuofi K, Tostevin P, Knight JR. Aspergillus mastoiditis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Skull Base. 2005;15:109–112. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sreepada GS, Kwartler JA. Skull base osteomyelitis secondary to malignant otitis externa. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:316–323. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soudry E, Joshua BZ, Sulkes J, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of malignant external otitis with facial paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:1002–1004. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.10.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amorosa L, Modugno GC, Pirodda A. Malignant external otitis: review and personal experience. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1996;521:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:327–360. doi: 10.1086/525258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vourexakis Z, Kos MI, Guyot JP. Atypical presentations of malignant otitis externa. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:1205–1208. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]