Abstract

Introduction

Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder is a common condition characterized by chronic pain and/or very painful acute episodes. Different treatments are used during painful flare-up, but they are often ineffective. US-guided percutaneous needle aspiration/lavage is proving to be an effective means for eliminating these calcifications.

Materials and methods

We treated 123 consecutive patients (mean age 48 years) with calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Fifty-five patients had persistent symptoms requiring 2 or more treatments with lavage and intrabursal steroid infiltration. Before and after treatment, US studies were done independently by 2 radiologists with experience in musculoskeletal ultrasound. Results were concordant in over 90% of the cases. Constant Shoulder Scores were calculated before and 6 months after treatment. At 6 months, MRI was performed to identify impingement and/or bursitis.

Results

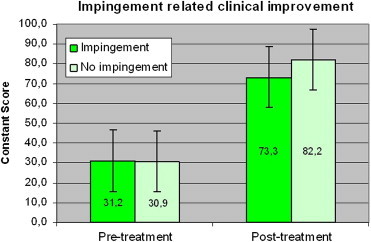

Post-treatment Constant scores were significantly improved in all 68 patients treated once (Group 1: mean scores 28.6 vs. 81.4) and in 52 of the 55 treated twice or more (Group 2: mean scores 34.1 vs. 71.1) (p < 0.0001 in both cases). Pretreatment Constant scores were similar in patients with and without shoulder impingement on MRI (31.2 vs. 30.9, respectively), but after treatment the impingement group’s scores were significantly higher (82.2 vs. 73.3, respectively; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

US-guided percutaneous needle aspiration/lavage is an effective and economic treatment for calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Pretreatment MRI should be done to check for impingement since it is often associated with an incomplete response to the first treatment.

Keywords: Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder, US-guided percutaneous treatment, Shoulder impingement, Subacromial bursal thickening

Sommario

Introduzione

La tendinopatia calcifica di spalla è una condizione relativamente frequente caratterizzata, quando sintomatica, da dolore cronico e da fasi di dolore acuto molto intenso.

Materiali e metodi

Da ottobre 2006 a marzo 2008 abbiamo trattato 126 spalle di 125 pazienti consecutivi. Tutti hanno eseguito Rx ed ecografia prima del trattamento ed il test di Constant prima del trattamento e a 6 mesi di distanza.

55 pazienti su 123 (42%) sono stati trattati due o più volte con infiltrazione intrabursale di corticosteroide. Tre pazienti hanno rifiutato altri trattamenti dopo il primo. Sono stati quindi raccolti i dati complessivamente di 123 spalle. È stata eseguita RM di controllo a sei mesi.

Risultati

Incremento del Constant Score dopo la procedura in tutti i pazienti trattati una sola volta ed in quasi tutti i pazienti trattati due volte; i pazienti sono stati divisi in due classi, rispettivamente trattati una o due (o più) volte. In ciascuna delle due classi c’è stato un significativo incremento (p < 0,0001)delle medie dei Cs pre e post trattamento; nella classe dei pazienti trattati due volte significatività statistica (p < 0,0001) tra le medie dei Cs rispettivamente prima del trattamento iniziale e dopo il primo trattamento, e tra la media Cs di quest’ultimo e quella dopo 6 mesi dal primo trattamento. Il Cs dopo il trattamento è significativamente diverso nei pazienti con impingement (p < 0,001).

Conclusion

Incremento del Cs, in più del 95% dei pazienti. Non lesioni tendinee ai controlli ecografici/RM. L’impingement è risultato un fattore di rischio per il risultato finale.

Introduction

Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder is a chronic condition caused by calcifications inside the rotator cuff tendons. It is characterized by recurrent episodes of pain associated with functional impairment and a subacute evolution [1]. It can be distinguished from other less common crystal arthritides by its peculiar radiological signs and the nature (hydroxyapatite) of the crystals [2–4].

Calcifications usually develop in the critical area of the tendon characterized by tenocytes with signs of fibrocartilaginous metaplasia, about 1.5 cm before the attachment to bone. The rest of the tendon is structurally normal [5,6]. The condition can remain asymptomatic for years [7], but as the calcifications become larger, they cause chemical inflammation and protrude into the bursa, leading to painful tendinitis and bursitis [8]. At the same time, the calcifications become soft and break into the bursa or the sub-bursal space [9].

After the first painful episode, some patients remain asymptomatic; others suffer from chronic recurrent pain. Focal thickening of the tendon causes continuous mechanical stimulation during joint movement, and the result is chronic bursal inflammation [10,11]. First-level treatment is always conservative, the aim being to allow spontaneous resolution [12,13]. Drug therapies include systemic administration of injectable NSAIDs or more active, local injections of corticosteroids. Other therapies (ultrasound or shock waves) can eliminate or reduce the volume of the calcification, and they are used in cases of chronic tendinitis [14]. Some patients do not respond to these therapies, and surgery is required in these cases [15,16].

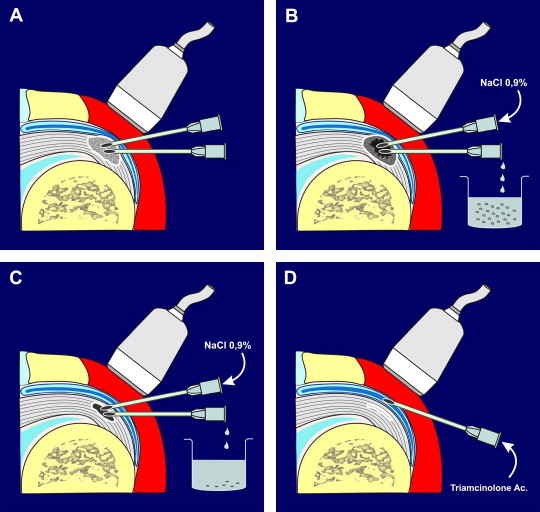

Recently [17–23], several groups have described their experiences with sonographically guided percutaneous treatment of calcifications with two needles, one for aspiration and the second for lavage (Fig. 1). This technique, which in past years was performed under fluoroscopic guidance, can significantly reduce the volume of calcifications and produce functional and clinical improvement [22,23].

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the main steps of the procedure we used. After the induction of local and intrabursal anesthesia, two needles are positioned inside the calcification under US guidance, with their tips facing one another (A). Saline solution is injected through one needle, while the calcium-containing lavage solution is aspirated with the other needle (B). When the cavity becomes distended during injection and collapses during aspiration, treatment can be terminated. A hyperechoic cap of fibrotic calcific material remains (C). Before withdrawing the needles, we usually inject 40 mg of triamcinolone acetate into the bursa.

Complete removal of all calcifications is usually not necessary. Elimination of some of the deposits generally causes spontaneous reabsorption of the remaining calcific material [24], and this approach produces good short- and long-term clinical results [22–26]. The Serafini group presented the results of largest study conducted thus far at the 2009 RSNA Congress, and their findings were similar to those of other authors.

The aim of this study was to analyze our group’s experience with this technique based on 6-month follow-up data (clinical assessment, MRI, and ultrasound). Ultrasonography makes it possible to visualize tendons, calcifications, and peritendinous structures [24,27–31] and to study the thickness of the subacromial bursa. MRI does not always allow detection of small calcifications, but it is a better tool for studying ligaments and their relations with tendons [3,9,32–34].

Materials and methods

From October 2006 to March 2008, we treated 125 consecutive patients (77 women, 46 men; age range 31–65 years; mean age 48 years) suffering from calcific tendinitis of the shoulder (total number of shoulders treated: 126). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Most of the patients had been symptomatic for more than a year and had already been treated with corticosteroid injections or other therapies such as US or shock waves. Before treatment, each patient underwent US and XR and completed the Constant Should Score test, the most widely used test in clinical and postoperative settings (more than the SPADI, the Shoulder Rating Scale, or the UCLA scoring system).

Fifty-five patients (42%) had persistent symptoms that required 2 or more treatments with lavage and corticosteroid infiltration of the bursa. Three patients refused a second treatment. They were referred to an orthopedic surgeon, but none of them had ruptured tendons at the US examination.

Therefore, we analyzed data for 123 patients.

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

-

-

calcification larger than 5 mm;

-

-

shoulder pain;

-

-

no sonographically detectable tendon lesions;

-

-

calcifications located more than 5 mm from the tendon insertion.

Patients were treated in the US room. Sonography was performed with Esaote Mylab and Technos MPX scanners with a high-frequency (12 MHz) linear probe and the osteoarticular program.

Needles (16- and 18-gauge) were positioned inside the calcified area under US guidance. Local and intrabursal anesthesia was achieved with 2% lidocaine.

-

•

Mean size of calcification: 15 mm.

-

•

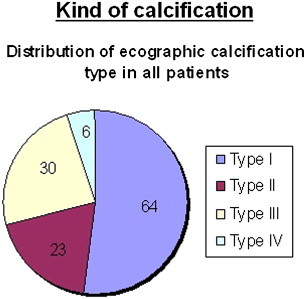

US type: type 1 (n = 64); type 2 (n = 23); type 3 (n = 30); type 4 (n = 6).

-

•

Site: supraspinatus tendon (n = 103); subscapular (n = 8); infraspinatus (n = 12).

Thirteen patients (3 from the retreated patient group, 10 from the non-retreated group) did not return for the 6-month MRI examination. Pre- and post-treatment MRI findings were not available for 1 patient in the non-retreated group and for 3 in the retreated group. All 123 patients completed the Constant test before and 6 months after treatment.

Pre- and post-treatment US studies were made independently by 2 radiologists with experience in musculoskeletal ultrasound. Results were concordant in over 90% of the cases.

The subacromial/subdeltoid bursa was classified at the time of the first treatment as normal (N), thickened (S), or fibroadhesive (F).

At the 6-month MRI assessment, findings were classified as normal (N), impingement (I), or bursitis (B).

Patients were treated in the supine position, and care was taken to maintain absolute sterility. Under US guidance, we positioned two 16- or 18-gauge needles inside the calcification, with their tips very close together. Physiologic saline was injected through one needle, producing a vortex that gradually eroded the calcification, and the saline solution containing the calcium fragments drains out through the second needle.

Procedure time ranged from 10 min to 45 min (depending on the size and consistency of the calcification). Care was taken to ensure that the needles tip were within the calcification. In the hardest calcifications, there was usually very little “dust like” material to aspirate; in the softer calcifications (which are usually very painful), we found toothpaste-like material. For the latter calcifications, it is possible to use a single needle because the material emerges spontaneously, even without aspiration.

At the end of the procedure, we injected 40 mg of triamcinolone acetate into the subacromial bursa (Figs. 1 and 2). Patients were instructed to rest the treated shoulder for 1 week (i.e., to avoid lifting weights). Thereafter, physiotherapy was prescribed. Not all patients complied with these prescriptions, and we do not have any data on the type or amount of physiotherapy they actually underwent.

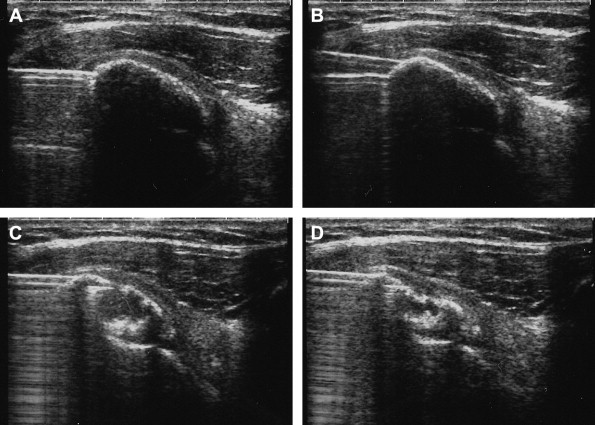

Fig. 2.

Main steps of the treatment. (A) The needle is positioned within the calcification (type 1 with shadow cone). (B) The second needle is positioned above the first one so that both can be clearly visualized. (C) After lavage and aspiration, the calcification collapses, and its shadow cone disappears. (D) The procedure is terminated when the aspirate contains only water without calcium. A hyperechoic, fibrocalcific cap remains.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the chi-squared test and Student t-test, as appropriate. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was carried out for each parameter to determine which characteristics were independently associated with the number of treatments. Analyses were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

The Constant score was corrected as described by Tavakkolizadeh et al. [35].

Results

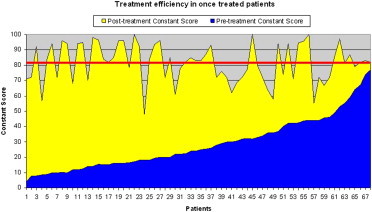

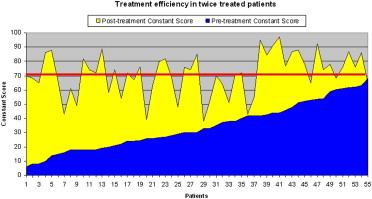

Constant scores recorded 6 months after treatment were higher than pretreatment scores in all patients who were treated only once (Graphic 1) and in all but 3 of those who were treated twice (Graphic 2). The Graphics 1 and 2 show the situations (the yellow area corresponds to clinical improvement).

Graphic 1.

Constant score before and 6 months after treatment increased in every patient only once treated (Graphic 1) and almost in everyone twice treated (only three of them didn’t improve, Graphic 2).

Graphic 2.

Constant score before and 6 months after treatment increased in every patient only once treated (Graphic 1) and almost in everyone twice treated (only three of them didn’t improve, Graphic 2).

Analysis of the mean pre- and post-treatment Constant scores for the two groups of patients (those treated once and those treated twice) revealed:

-

-

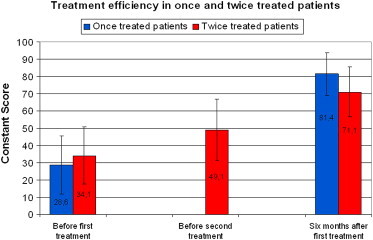

Significant differences between the mean pre- and post-treatment Constant scores for the single-treatment and two-treatment groups (pretreatment: 28.6 vs. 34.1; p < 0.05; post-treatment: 81.4 vs. 71.1; p < 0.05);

-

-

Highly significant differences (p < 0.0001) between the mean pre- and post-treatment Constant scores of each group (28.6 vs. 81.4 for the single-treatment group; 34.1 vs. 71.1 for the two-treatment group);

-

-

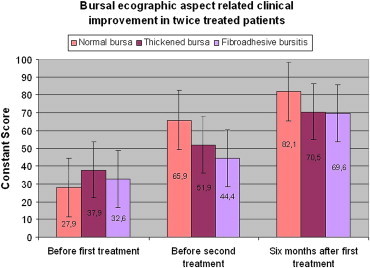

In the two-treatment group, there were also significant differences (p < 0.0001) between the mean scores recorded before the first and second treatments (34.1 and 49.1, respectively) and between the score recorded before the second treatment and the one recorded at the 6-month follow-up (49.1 and 71.1, respectively; Graphic 3). These patients had little improvement after the first treatment. They usually reported that the results were very good for the first two or three months, but the symptoms worsened thereafter (although they were never as severe as they were before the first treatment).

Graphic 3.

In the two treatments class (p < 0.0001) significant statistical difference between media of Cs before the first treatment (34.1) and that before the second one (49.1) and between the latter and the Cs media 6 months after the first one (71.1).

We then evaluated correlation between the Constant score and the following parameters:

-

-

US appearance of the bursa during the first and (when applicable) second treatment;

-

-

US appearance of the tendon during the first treatment;

-

-

US classification of the calcification;

-

-

Impingement at the 6-month follow-up MRI.

Bursa

After distension with physiological saline, the bursae appeared:

-

1)

normal;

-

2)

thickened but distensible;

-

3)

thickened and frayed with limited or no distention (fibroadhesive).

-

-

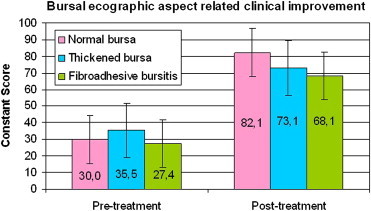

Significant differences between the post-treatment Constant scores (p < 0.0001) of subgroups with normal vs. thickened vs. fibroadhesive bursae (Graphic 4).

-

-

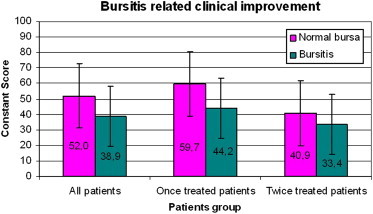

Improvement in the Constant score was greater among patients with normal bursas in the pretreatment US examination (vs. those who presented evidence of bursitis). The difference was statistically significant for the total patient population (p < 0.001) and for the single-treatment subgroup (p < 0.01), but not for the two-treatment group (Graphic 5). This suggests that in some cases, the treatment can cause bursal thickening. These patients tend to have final Constant scores comparable to those of the patients with pretreatment bursal thickening.

Graphic 4.

Significant statistical difference in post-treatment Constant score scale (p < 0.0001) between patients with normal bursa, thickened and fibroadhesive bursa.

Graphic 5.

Improvement in Cs scale was better in the normal bursa patients class than in the bursitis patients one in the pretreatment US examination; it is a significant statistical difference if we consider all patients (p < 0.001) or the one treatment class patients (p < 0.01), but not significant in the retreatment class.

In the 55 patients treated twice, the US bursal findings we observed were as follows (Table 1):

Table 1.

US bursal findings at the first and second treatment.

| Bursa | First treatment | % | Second treatment | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 26 | 47% | 5 | 9% |

| Thickened | 19 | 35% | 20 | 36% |

| Fibroadhesive | 10 | 18% | 30 | 55% |

| Total | 55 | 100% | 55 | 100% |

-

-

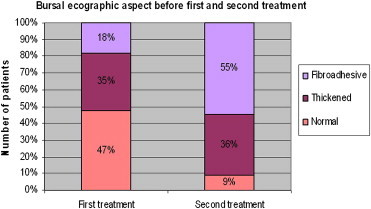

At the time of the first treatment, the bursa appeared normal on US in 26 patients (47%). The others had bursitis: 19 patients (35%) had a thickened bursa (chronic bursitis), and 10 (18%) had fibroadhesive changes (Graphic 6).

-

-

At the time of the second treatment, only 5 (9%) patients had a normal bursa, 20 (36%) had thickened bursa, and 30 (55%) had fibroadhesive changes.

Graphic 6.

At the time of the first treatment 26 patients (47%) had a normal US bursa aspect. The others had bursitis: 19 patients (35%) had thickened bursa (chronic bursitis), while 10 patients (18%) had fibroadhesive aspects.

Twenty-one patients whose bursas were normal at the time of the first treatment subsequently developed bursal thickening. Ten of these had a thickened bursae, and 11 had fibroadhesive changes at the time of the second treatment.

In addition, 10 patients with thickened bursas at the time of the first treatment subsequently developed fibroadhesive changes that were recognized during the second treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients with thickened bursa at the time of the first treatment developed a fibroadhesive one, recognized during the second treatment.

| Second treatment |

TOT | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | T | F | ||||

| First treatment | N | 5 | 10 | 11 | 26 | 47.3% |

| T | 0 | 9 | 10 | 19 | 34.5% | |

| F | 0 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 18.2% | |

| TOT | 5 | 20 | 30 | 55 | 100.0% | |

| % | 9.1% | 36.4% | 54.5% | 100.0% | ||

Correlation between US appearance of the bursa and Constant score:

-

-

No significant difference between the 3 classes of bursa in terms of the pre- or post-treatment Constant scores.

-

-

In all 3 classes of bursa, the score improved significantly after treatment (Graphic 7).

Graphic 7.

No significant statistical difference in the Cs scale of the three kind of bursa before and after treatments. Significant improvement of Cs scale of each the three kind of bursa in the control after treatment.

Tendons

Pretreatment Constant scores were not significantly different in patients with normal vs. degenerated tendons (30.1 vs. 34.6), but significant differences were seen in the post-treatment scores of these two groups (78.2 vs. 71.7; p < 0,05; Graphic 8).

Graphic 8.

Patients with normal tendon (30.1) and those with degenerated one (34.6) didn’t show statistical difference in the pretreatment Cs, instead it was significant in the post-treatment control (78.2 vs. 71.7; p < 0.05).

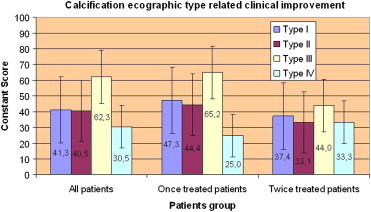

Kind of calcification

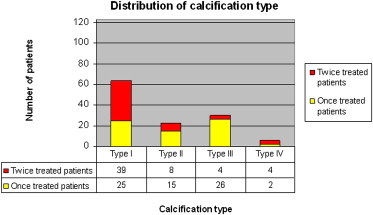

Patients with type 3 calcifications usually needed only one treatment: two treatments were required in only 13%. These results are even better than those reported by del Cura [23]. We think that using two needles improves the results by facilitating more complete lavage (Graphics 9 and 10).

Graphic 9.

Most of treated patients (64, 52%) had type one calcification at US. 30 patients (24.4%) had type 3, 23 patients (18.7%) type 2 and only 6 patients (4.9%) type 4.

Graphic 10.

Distribution of calcification in relation to one and two treatments.

Type 1 calcifications improved less after the first lavage than type 3 calcifications. This may be due to the development of bursitis secondary to the post-treatment migration of tiny crystal fragments from the calcification area to the subdeltoid bursa.

Six months after treatment, significant improvement was seen in all types of calcification (p < 0.01) (Graphic 11).

Graphic 11.

In every kind of calcification a significant improvement was seen (p < 0.01) after 6 months.

Among the patients who were treated once, type 3 calcifications showed the most marked improvement (p < 0.01) (Graphic 12).

Graphic 12.

Type 3 calcifications had the best improvement (p < 0.01) if we consider the once treated patients.

Impingement

Pretreatment Constant scores were not significantly different in patients with or without impingement (31.2 vs. 30.9), but post-treatment scores were significantly different (p < 0.001) (82.2 vs. 73.3; Graphic 13).

Graphic 13.

Cs before treatment: impingement (31.2) and without impingement (30.9) is not significant, while after treatment the difference is significant (p < 0.001) (82.2 vs. 73.3).

At the 6-month visit, MRI showed no signs of tendon rupture, but in 31 patients signal alterations were observed at the site of treatment. There was no clinical evidence of rupture in these cases, and repeat MRI performed some months later demonstrated improvement with nearly normal signals in all patients. Care should thus be taken to avoid confusing these signal anomalies with tendon ruptures.

Discussion

In our study, as in many others, calcific tendinopathy of the shoulder was more frequent in women 40–50 years old.

Subacromial impingement was more frequent than in other studies (16% as reported by Loew). This difference may be due to the fact that we used MRI imaging, which is more sensitive, even in the early phases of the disease.

Impingement proved to be a risk factor for an unsatisfactory clinical response to the first treatment. For this reason, we feel that diagnostic MRI should always be performed before treatment to determine whether multiple treatment sessions will be required. We also noted that fibroadhesive bursitis developed after the first treatment in some patients (including those with normal bursas before treatment). In our opinion, this was caused by the introduction of tiny crystal fragments into the bursa. In these cases, we preferred to distend and separate/detach the thickened walls. Almost all the patients reported rapid and lasting improvement. Some patients (5%) needed a third treatment for the same reasons.

We noted particularly good results in patients with US type 3 calcifications, probably because the acute phase is very painful, and the patients felt much better soon after treatment. In these cases, a single-needle technique can probably be used because as soon as the needle penetrates the calcification, a toothpaste-like material oozes out; in our experience however the lavage and aspiration, with a second needle aid, is more effective. These are typically patients who come to the emergency room in severe pain with acute calcific tendinitis. They are less likely to require a second treatment, possibly because the calcification is not composed of microcrystals. They are also less likely to develop post-treatment bursitis.

Most of the patients with type 1 calcifications had long histories of pain, but it was not usually unbearable. They came to us after unsuccessful treatment with shock waves, ultrasound, or general physiotherapy.

We found that bursal thickening before treatment, possibly linked to impingement, was generally associated with the need for more than one treatment. In these cases, the clinical outcome of treatment was worse than that observed in patients with normal bursas. We noted, however, that fibroadhesive bursal changes seen during the second treatment was sometimes a consequence of the first treatment. It may be related to the migration of microcrystals from the calcification into bursa. It is mandatory in these cases to distend the bursa with saline solution and separate the walls. Bursal lavage with one or two needles followed by injection of a slow-acting corticosteroid may also be necessary. We are currently testing a protocol aimed at the prevention of fibroadhesive bursitis. It provides for a well-defined course of physical therapy for all patients, and for those still experiencing symptoms after the first treatment, physical therapy is preceded by high-precision shockwave therapy. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of needle aspiration of calcifications, its possible consequences (especially in the tendon), and percutaneous therapies. We prescribed physiotherapy for all our patients, but only some of them followed this prescription; we did not verify the type of physiotherapy they had. Our future aim is to compare the efficacy of a second treatment for bursitis with that of a well-defined program of physiotherapy in our institution. We obtained good results, measured in terms of pre- and post-treatment Constant scores, in over 95% of the patients. The technique we use is not expensive and it allows real-time visualization of the calcification removal process.

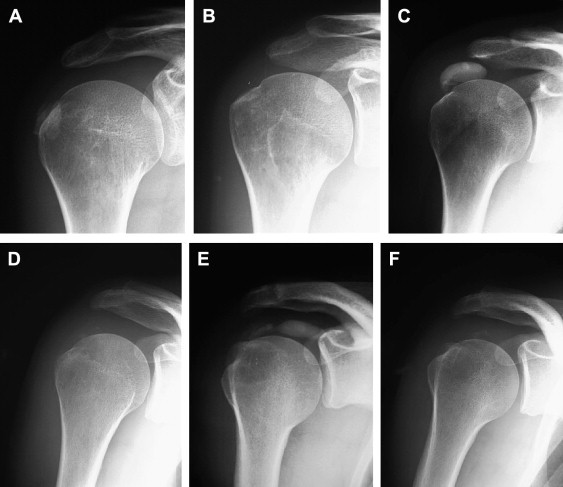

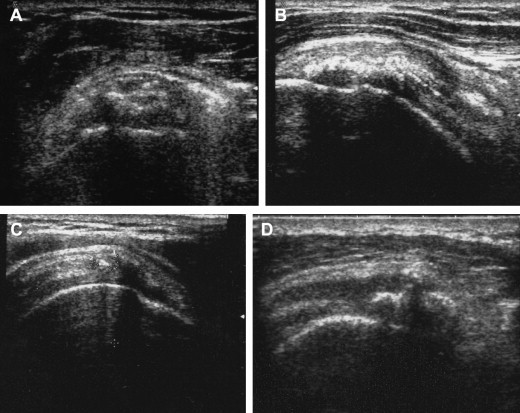

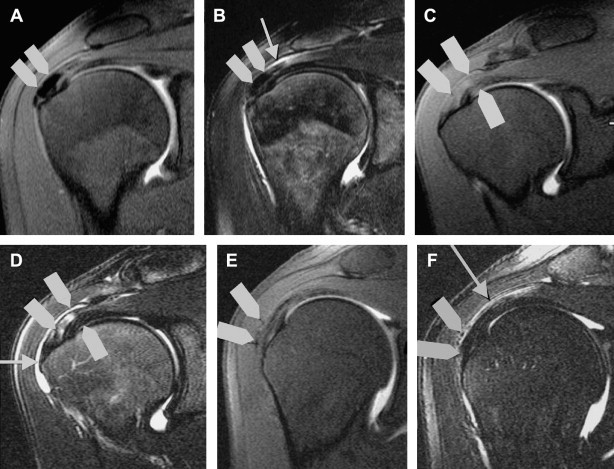

After treatment, the shoulder was sometimes examined with XR (Fig. 3) and US (Fig. 5). All were examined with MRI (Fig. 4). The XR and US studies sometimes revealed the presence of residual calcifications, but this finding was unrelated to symptoms. The US examination always showed residual hyperechoic structures at the treatment site: these represent the capsule of the calcifying mass.

Fig. 3.

Reduction of calcification volume after US guide percutaneous treatment.

Fig. 5.

Typical post-treatment evolution of US findings in calcific tendinopathy. A lenticular image sometimes remains. It represents the cap of the calcification not totally collapsed (A). The tendon appears hyperechoic at the site of treatment (B). Some months later, the tendon may be completely normal, with a mildly inhomogeneous structure and a few hyperechoic spots (C). One or more calcifications may be present (D).

Fig. 4.

MRI: evolving steps after treatments. Immediately after treatment, tendon fibers appear hyperintense in T2 and TIRM sequences, and there are usually signs of inflammation at the level of the subacromial bursa. The calcification itself is no longer visible. Six months or more after treatment, the tendon appears normal, but there are still signs of mild bursitis. In many cases, the patient is asymptomatic at this point.

The physical examination revealed no symptoms of tendon lesion, even when there was some doubt at the MRI examination. The latter finding is caused by signal changes related to tissue repair at the site of the calcification (Fig. 4).

We think that this technique should be more widely used. It must be carried out by radiologists with specific training in musculoskeletal and interventional ultrasound.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of inetrest.

Footnotes

Award for the best Oral Communication presented at 19th SIUMB Congress.

References

- 1.Uhthoff H.K., Sarkar K. Calcifyng tendinitis. In: Rockwood C.A. Jr., Matsen F.A. III, editors. The shoulder. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1990. pp. 774–790. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick D. Malattia da deposizione di cristalli di idrossiapatite di calcio. In: Resnick D., editor. Imaging dell’apparato muscoloscheletrico. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2003. pp. 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speed C.A., Hazleman B.L. Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(20):1582–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905203402011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada J., Ono W., Tamai K., Saotome K., Hoshino T. Analysis of calcium deposits in calcific periarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(4):809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace D., Carr A. Calcifying tendinitis. In: Bulstrode C., editor. Oxford textbook of orthopaedics and trauma. Oxford University Publ; Oxford: 2002. pp. 739–743. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurt G., Baker C.L. Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:567–575. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(03)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes W.C., Conway W.F. Calcium hydroxyapatite deposition disease. Radiographics. 1990;10:1031–1048. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.10.6.2175444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhthoff H.K., Loehr J.W. Calcific tendinopathy of the rotator cuff: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(4):183–191. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serafini G. La tendinopatia calcifica. In: Busilacchi P., Rapaccini G.L., editors. Ecografia clinica. Idelson-Gnocchi; 2006. pp. 510–523. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost A., Robinson M.C. The painful shoulder. Orthopaedic II: soft tissue, metabolism and malignancy. Surgery (Oxford) 2006;24(11):363–367. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohr W., Bilger S. Basic morphologic structures of calcified tendinopathy and their significance for pathogenesis. Z Rheumathol. 1990;49:346–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolk T., Wittenberg R.H. Calcifying subacromial syndrome: clinical and ultrasound outcome of non-surgical therapy. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1997;135(5):451–457. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cailliet R. EDI Lombardo; Roma: 1990. Il dolore scapoloomerale. pp. 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebenbichler G.R., Erdogmus C.B., Resch K.L., Funovics M.A., Franz K., Georg B. Ultrasound therapy for calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(20):1533–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905203402002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rochwerger A., Franceschi J.P., Viton J.M., Roux H., Mattei J.P. Surgical management of calcific tendonitis of the shoulder. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18(4):313–316. doi: 10.1007/s100670050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ark J.W., Flock T.J., Flatow E.L., Bigliani L.U. Arthroscopic tratment of calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1992;8(2):183–188. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(92)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley M., Bhamra M.S., Robson M.J. Ultrasound guided aspiration of symptomatic supraspinatus calcific deposits. Br J Radiol. 1995 Jul;68(811):716–719. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-68-811-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farin P.U., Rasanen H., Jaroma H. Rotator cuff calcifications: treatment with ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle aspiration and lavage. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:551–555. doi: 10.1007/s002560050133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacomoni P., Siliotto R. Echo-guided percutaneous treatment of chronic calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Radiol Med. 1999;98:386–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aina R., Cardinal E., Bureau N.J., Aubin B., Brassard P. Calcific shoulder tendinitis: treatment with modified US-guided fine needle technique. Radiology. 2001;221:455–461. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2212000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galletti S., Magnani M., Rotini R., Mignani G., Affinito D., Pelotti P. The echo-guided treatment of calcifica tendinitis of the shoulder. Chir Organi Mov. 2004;89(4):319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J.T., Adler R.S., Bracilovic A., Cooper G., Sofka C., Lutz G.E. Clinical outcomes of ultrasound guided aspiration and lavage in calcific tendinosis of the shoulder. HSSJ. 2007;3:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s11420-006-9037-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.del Cura J.L., Torre I., Zabala R., Legorburu A. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle lavage in calcific tendinitis of the shoulder: short- and long term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:128–134. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comfort T.H., Arafiles R.P. Barbotage off the shoulder with image-intensified fluoroscopic control of needle placement for calcified tendinitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978 Sep;(135):171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Normandin C., Seban E., Laredo J.D. Aspiration of tendinous calcific deposits. In: Bard M., Laredo J.D., editors. Interventional radiology in bone and joints. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1988. pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serafini G. Il trattamento percutaneo sotto guida ecografica della tendinopatia calcifica della cuffia dei rotatori. Risultati in 651 in 8 anni. Radiol Med. 2004;107(Suppl. 1):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farin P.U., Jaroma H., Soimakallio S. Rotator cuff calcifications: treatment with US-guided technique. Radiology. 1995;195:841–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarty D.J., Jr., Gatter R.A. Recurrent acute inflammation associated with focal apatite crystal deposition. Arthritis Rheum. 1966;9:804–819. doi: 10.1002/art.1780090608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gondos B. Observations on periarthritis calcarea. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1957 Jan;77(1):93–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farin P.U. Consistency of rotator-cuff calcifications. Observations on plain radiography, sonography, computered tomography, and at needle treatment. Invest Radiol. 1996;31(5):300–304. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199605000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uhthoff H.K., Sarkar K., Maynard J.A. Calcyfing tendinitis: a new concept of its pathogenesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976 Jul–Aug;(118):164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loew M., Sabo D., Wehrle M., Mau H. Relationship between calcifying tendinitis and subacromial impingement: a prospective radiography and magnetic resonance imaging study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(4):314–319. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(96)80059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zubler C., Mengiardi B., Shmidt M.R., Hodler J., Jost B., Pfirrmann C.W. MR arthrography in calcific tendinitis of the shoulder: diagnostic performance and pitfalls. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1603–1610. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung C.B., Dwek J.R., Cho G.J., Lektrakul N., Trudell D., Resnick D. Rotator cuff interval: evaluation with MR imaging and MR arthrography of the shoulder in 32 cadavers. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:738–743. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200009000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tavakkolizadeh A., Ghassemi A., Colegate-Stone T., Latif A., Sinha J. Gender-specific constant score correction for age. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:529–533. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]