Abstract

Thyroid cysts and pseudocysts, or hemorrhagic cysts, are quite frequent thyroid pathologies. Surgical theraphy has always been the treatment of choice in this pathology, but percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) is becoming still more common. PEI was originally used in the treatment of liver nodules and subsequently in solid, hyperfunctioning thyroid nodules, but today it is used exclusively in cysts. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of PEI in reducing thyroid cyst volume 12 and 84 months after treatment and to compare cost-benefit to that of surgical treatment. The study includes 110 consecutive patients, who all underwent PEI after cytological analysis had excluded the presence of neoplasia. All patients had refused surgical treatment. One patient died during the follow-up due to cerebral hemorrhage. Each patient received an average of 5.3 ± 2.7 PEI treatments. After 12 months, volume was reduced by 82.6% and after 84 months by 93.03%. Dysphonia occurred in 2 cases of which one resolved spontaneously and one received cortisone therapy. The cost of PEI treatment is considerably lower than the cost of surgical therapy (the cost saving in our patient population was about €200,000). PEI should therefore be preferred to surgical treatment due to its efficacy and lower cost.

Keywords: Percutaneous ethanol injection therapy, Thyroid US, Thyroid cysts

Sommario

Le cisti e le pseudo cisti tiroidee o cisti emorragiche sono una patologia abbastanza frequente tra quelle tiroidee. La terapia d'elezione è sempre stata quella chirurgica, ma prende sempre più piede l'alcolizzazione per via percutanea (PEI). La PEI è una terapia derivata da quella dei noduli epatici. Utilizzata inizialmente per i noduli solidi iperfunzionanti, è oggi utilizzata esclusivamente sulle cisti. Scopo di questo studio è stato quello di valutare l'efficacia della PEI sulla riduzione volumetrica delle cisti tiroidee dopo 12 e 84 mesi e di confrontare il rapporto costo-beneficio con la chirurgia. Sono stati considerati in serie successiva 110 pazienti, tutti trattati mediante alcolizzazione previo studio citologico che escludeva una patologia neoplastica. Tutti i soggetti avevano rifiutato l'intervento chirurgico. Uno dei pazienti è deceduto durante il follow-up per ictus cerebri. Ogni paziente è stato sottoposto in media a 5.3 ± 2.7 sedute. Dopo 12 mesi la riduzione volumetrica è stata del 82.6%; dopo 84 mesi del 93.03%. Gli effetti collaterali come la disfonia con risoluzione spontanea si sono verificati in 2 soli casi. Inoltre, comparando i costi della PEI con l'intervento chirurgico si evince un risparmio (per quanto riguarda i nostri soggetti) di circa 200.000 euro. Quindi la PEI si pone come prima scelta nei confronti della chirurgia sia per l'efficacia, sia per il risparmio economico da parte del SSN.

Introduction

Percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (PEI) in thyroid nodules is a treatment which was originally used in liver nodules (primary and secondary neoplastic lesions). Initially it was used in the treatment of solid and hyperfunctioning thyroid nodules such as Plummer's disease [1–4] or warm nodules in multinodular goiter [5].

Today, PEI is only rarely used in the treatment of solid, hyperfunctioning nodules, but it is increasingly being used in the treatment of thyroid cysts and pseudocysts [6–8]. US-guided PEI is increasingly common as an alternative to surgery [9,10] particularly in view of the nodule volume reduction [11,12] and low cost. Histological changes found in a cyst submitted to surgical removal 12 months after PEI treatment due to onset of Flajani-Basedow syndrome was characterized by interstitial edema, coagulative necrosis and granulation tissue with multinucleated giant cells. The surrounding thyroid tissue showed no sign of regression and no lymphocytic infiltration [13].

The aim of this study was to analyze the efficacy of PEI in reducing thyroid cyst and pseudocysts volume evaluated 12 and 84 months after treatment, to evaluate possible recurrent cysts and/or complications and to compare the cost of PEI with that of surgical treatment.

Materials and methods

From 2001 to 2007 a series of 110 consecutive patients underwent PEI treatment of thyroid cysts and pseudocysts; 80 were females (76%) and 30 were males (24%); mean age 42.1 ± 14.7 years. One patient did not finish the 7-year follow-up as he died due to cerebral hemorrhage.

Of the remaining 109 patients, 100 were euthyroid, 7 had latent hyperthyroidism and only 2 had confirmed hyperthyroidism. In all patients, cytological analysis which was obligatory prior to PEI, resulted negative for neoplastic pathologies.

All patients had refused surgery. Before PEI treatment was started, written informed consent was obtained from all patients after detailed explanation related to the treatment which was administered once a week as an out-patient procedure. The following materials were used: a 22 gauge spinal needle, 75 mm long with an inner mandrin (Becton-Dickinson), 95% ethyl alcohol (SALF) and 2% Mepivacaine chlorhydrate (Angelini) used for anesthesia. US equipment was Aloka 5000 (Tokyo, Japan) with a multi-frequency 7.5–13 MHz probe. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS Advanced Statistical TM 7.5 software (1977; Chicago, Illinois, USA). Cystic volume was calculated using the ellipsoid formula (D1 × D2 × D3 × 0.52).

For the PEI treatment, the patient lay supine with the neck hyperextended; the US operator was sitting next to the bed and the PEI operator was standing up behind the patient's head. In all patients the “free hand” technique for ultrasound guided needle insertion was used, i.e. without a guiding device mounted on the US probe, as we find that this technique allows a more accurate positioning of the needle inside the cystic nodule while leaving the probe and the operator the possibility to move freely.

The PEI procedure includes various phases. Before alcoholization, the nodule is emptied of its liquid contents (Fig. 1). Subsequently, without withdrawing the needle, the syringe is changed and 0.5–1 cc anesthetic is injected to anesthetize the area and to obtain a clear view of the needle tip (Fig. 2). The anesthetic syringe is then substituted with a syringe containing ethyl alcohol in a quantity equal to 25% of the extracted cystic liquid. The distribution of alcohol within the cyst creates a hyperechoic image which rapidly disappears (Fig. 3). During the injection, the patient is asked to pronounce some words in order to immediately suspend treatment in case chemical irritation of the recurrent nerve should occur. After alcoholization, before the needle is withdrawn, more anesthetic (0.5–1 cc) is injected, and the inner mandrin is reintroduced through the needle to prevent back-diffusion of alcohol along the needle tract and consequent unnecessary pain.

Fig. 1.

The nodule is emptied of its liquid contents before anesthetic is injected.

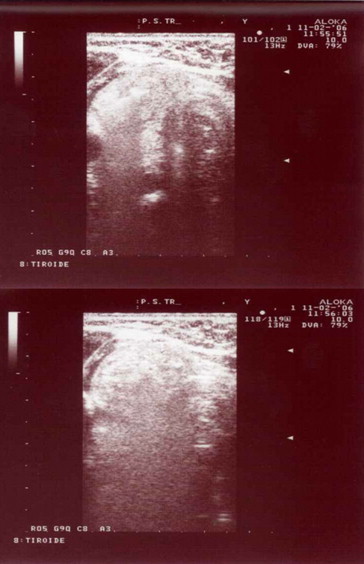

Fig. 2.

Anesthetic is injected to anesthetize the area and to obtain a clear view of the needle tip.

Fig. 3.

The distribution of alcohol within the cyst creates a hyperechoic image which rapidly disappears.

When PEI treatment is completed, the patient is asked to get up and to exercise pressure on a tampon placed on the puncture site which will subsequently be covered with plaster. The patient must remain under close observation by medical and paramedical staff for about 20 min and can then leave the clinic. When the cycle of PEI treatments is completed, follow-up is performed at 3, 6 and 12 months and then once a year.

Results

Out of the 110 patients enrolled in this study, only 109 concluded the follow-up as one patient died due to cerebral hemorrhage. In 100 patients the thyroid was well functioning whereas 7 had latent hyperthyroidism and 2 were affected by confirmed hyperthyroidism. The mean volume of the cysts before treatment was 15.0 ± 18.8 cc, varying from a minimum of 14.2 cc in euthyroid patients to 28.9 cc in patients with latent or confirmed hyperthyroidism. Twelve months after treatment, the nodule volume was significantly reduced resulting in a mean reduction of 82.6% (p < 0.001), reaching 93.03% (p < 0.001) after 84 months (Figs. 4 and 5). Twelve months after treatment, the most significant volume reduction was observed in euthyroid patients (87.7%), and the least significant volume reduction (61.2%) was observed in patients affected by hyperthyroidism. This latter group did in fact not present a significantly reduced volume within the first 12 months after treatment, but a significant reduction was observed during the period from 12 months (mean value 11.25 cc) to 84 months (mean value 0.46 cc). However, this result has no statistic relevance as it is related to 2 patients only. Pre-treatment cystic volume was 25.2 ± 26.8 cc in the male patients and 11.1 ± 12.9 cc in the female patients; this difference was found statistically significant (p < 0.001). Mean reduction expressed in percentages after 84 months was 89.7% in the male patients and 94.7% in the female patients (Figs. 6 and 7); this sex-related difference was not found statistically significant. We also examined the possibility of a correlation between pre-treatment cystic volume, reduction after 84-month and the patient's age. The values of the correlation coefficients were R = a 0.114 and R = a 0.092, respectively, so neither of these correlations were found statistically significant. On the contrary, correlation between pre-treatment cystic volume and the number of PEI treatments was found statistically significant resulting in R = a 0.542; (p < 0.01) (Fig. 8). In this study each patient underwent an average of 5.3 ± 2.7 (median 4) PEI treatments, and the mean value expressed in cc of 95% ethyl alcohol injected in each patient was 10.4 ± 9.9 cc.

Fig. 4.

Mean values ± 2SE of cystic volumes at the various follow-up. * p < 0.001; the student T-Test (two tailed); before treatment. † p < 0.001; the student T-Test (two tailed); 12 months after treatment.

Fig. 5.

Mean values ± SD of cystic volume reduction expressed in percentages related to the 84-month follow-up and to the intermediate periods from pre-treatment to 12 months and from 12 months to 84 months.

Fig. 6.

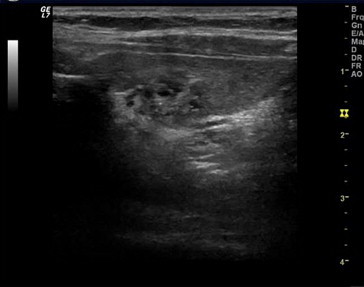

Follow-up using power Doppler US; small vessels are visible particularly around the residual cyst.

Fig. 7.

US follow-up after treatment: note the residual cystic area.

Fig. 8.

Mean values ± SD of sex-specific reduction of cystic volume at 84 months expressed in percentages.

Conclusions

PEI has proved an extremely effective treatment in thyroid cysts and pseudocysts. It is easy to perform and hospitalization is not required as the procedure can be carried out as an out-patient procedure with few and only transient complications. Potentially, the most serious complication is transient dysphonia which occurs if the recurrent nerve is damaged by ethyl alcohol. In our experience, leakage of alcohol outside the cyst occurred in two cases. In the first case, the patient swallowed during alcohol injection resulting in a dysphonia which resolved spontaneously within 24 h. In the second case, alcohol injection velocity combined with inadequate US monitoring of a leakage towards the posterior region and the lower thyroid lobe caused chemical irritation of the homolateral recurrent nerve and severe dysphonia. The patient was administered low-dose Methylprednisolone therapy for 15 days. The recurrent nerve damage healed in 5 weeks resulting in normal outcome of laryngoscopic examination and full recovery of the normal voice.

It is a well-known fact that disease management also has to evaluate treatment costs. In this study we therefore analyzed the expenditure by comparing the cost of PEI treatment to that of surgical treatment considering that medical therapy is totally ineffective in this pathology. According to the national tariff, each PEI treatment is remunerated with €76.75, amounting to a total remuneration of €44,515 for 580 treatments. A comparison of the cost of a PEI cycle with that of a thyroid lobectomy, which is the surgical treatment of choice in thyroid cysts and pseudocysts, shows a substantially lower expenditure in connection with PEI. According to the national tariff, the cost of a lobectomy is €2.245, amounting to a total cost of €244.705 for 109 lobectomies. This resulted in the saving of over €200,000 related to the patients enrolled in this study.

In conclusion, PEI should be preferred to surgery in this pathology due to its effectiveness in reducing the volume of cystic nodules, the absence of relapses, the very low complication rates, and because it is easy to perform, and not least for the significant savings on the national health service budget.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Livraghi T., Paracchi A., Ferrari C., Bergonzi M., Garavaglia G., Ranieri P. Treatment of autonomous thyroid nodules with percutaneous ethanol injection: preliminary results. Work in progress. Radiology. 1990;175:827–829. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monzani F., Goletti O., De Negri F., Del Guerra P., Lippolis P.V., Caraccio N. Autonomous thyroid nodules and percutaneous ethanol injection. Lancet. 1991 Mar 23;337(8743):743. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90338-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paracchi A., Ferrari C., Livraghi T., Reschini E., Macchi R.M., Bergonzi M. Percutaneous intranodular ethanol injection: a new treatment for autonomous thyroid adenoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:353–362. doi: 10.1007/BF03348753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papini E., Panunzi C., Pacella C.M., Bizzari G., Fabbrini R., Petrucci L. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided ethanol injection: a new treatment of toxic autonomously functioning thyroid nodules? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:411–416. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.2.8432784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livraghi T., Paracchi A., Ferrari C., Reschini E., Macchi R.M., Bonifacino A. Treatment of autonomous thyroid nodules with percutaneous ethanol injection: 4-year experience. Radiology. 1994;190:529–533. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.2.8284411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monzani F., Lippi F., Goletti O., Del Guerra P., Caraccio N., Lippolis P.V. Percutaneous aspiration and ethanol sclerotherapy for thyroid cysts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(3):800–802. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.3.8126160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zingrillo M., Torlontano M., Ghiggi M.R., D'Aloiso L., Nirchio V., Bisceglia M. Percutaneous ethanol injection of large thyroid cystic nodules. Thyroid. 1996;6:403–408. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guglielmi R., Pacella C.M., Bianchini A., Bizzari G., Rinaldi R., Graziano F.M. Percutaneous ethanol injection treatment in benign thyroid lesions: role and efficacy. Thyroid. 2004;14:125–131. doi: 10.1089/105072504322880364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raggiunti B, Giandonato S, Tritella T, Montani V, Di Berardino P. Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) come alternativa alla chirurgia nelle cisti e pseudocisti tiroidee. Atti XV Giornate Italiane della Tiroide, Venezia, 4–6 dic, SP2, pagina 5, 1997.

- 10.Colombo C., Paletto A.E. Minerva Medica SpA; 2001. Trattato di Chirurgia. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S.J., Ahn I.M. Effectiveness of percutaneous ethanol injection therapy in benign nodular and cystic thyroid diseases: long-term follow-up experience. Endocr J. 2005;52:455–462. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.52.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meskhi I., Sikharulidze E., Lomidze N., Mizandari M., Natmeladze K. Effectiveness of percutaneous ethanol injection therapy in benign nodular and cystic thyroid diseases: 12-month follow-up experience. Georgian Med News. 2006;140:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crescenzi A., Papini E., Pacella C.M., Rinaldi R., Panunzi C., Petrucci L. Morphological changes in a hyperfunctioning thyroid adenoma after percutaneous ethanol injection: histological, enzymatic and sub-microscopical alterations. J Endocrinol Invest. 1996;19:371–376. doi: 10.1007/BF03344972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]