Abstract

Efficient apoptotic corpse clearance is essential for metazoan development and adult tissue homeostasis. Several autophagy proteins have been previously shown to function in apoptotic cell clearance; however, it remains unknown whether autophagy genes are essential for efficient apoptotic corpse clearance in the developing embryo. Here we show that, in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos, loss-of-function mutations in several autophagy genes that act at distinct steps in the autophagy pathway resulted in increased numbers of cell corpses and delayed cell corpse clearance. Further analysis of embryos with a null mutation in bec-1, the C. elegans ortholog of yeast VPS30/ATG6/mammalian beclin 1 (BECN1), revealed normal phosphatidylserine exposure on dying cells. Moreover, the corpse clearance defects of bec-1(ok691) embryos were rescued by BEC-1 expression in engulfing cells, and bec-1(ok691) enhanced corpse clearance defects in nematodes with simultaneous mutations in the engulfment genes, ced-1, ced-6 or ced-12. Together, these data demonstrate that autophagy proteins play an important role in cell corpse clearance during nematode embryonic development, and likely function in parallel to known pathways involved in corpse removal.

Keywords: autophagy, apoptotic corpse clearance, C. elegans, embryogenesis, cell death

Introduction

Apoptosis is a conserved process that removes unwanted cells, and its proper regulation is essential for normal development and tissue homeostasis. Not only is the execution of cell killing tightly controlled, the removal of apoptotic corpses is also highly regulated, and defects in apoptotic cell corpse clearance contribute to inflammation and autoimmunity.1,2 Upon cell death execution, apoptotic cells display markers, so-called “eat-me” signals, that signal neighboring cells or specialized phagocytes to internalize and degrade the dead cell corpses. The best-studied “eat-me” signal is the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the apoptotic cell membrane,3 although other cell death markers such as altered sugar moieties and other phospholipids are also important in labeling corpses for engulfment.4

The engulfment of apoptotic cell corpses is controlled by two evolutionarily conserved, partially redundant pathways that were discovered primarily through genetic studies in the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans.5,6 The first pathway, composed of CED-1, CED-6, CED-7 and DYN-1 proteins, is important for promoting membrane expansion of pseudopods during engulfment and for the degradation of apoptotic cells inside phagosomes.7,8 The second pathway includes the CED-2, CED-5 and CED-12 proteins that are important for cytoskeletal reorganization during apoptotic corpse removal, and that function upstream of the Rho family GTPase CED-10 (RAC1).5,9 CED-10 may also mediate certain activities of the CED-1 pathway.7,9 Phagosomes containing engulfed cell corpses mature by sequentially recruiting proteins including PtdIns3-kinases, Rab GTPases, and the homotypic fusion and vacuole protein sorting (HOPS) complex, leading to the formation of phagolysosomes wherein the engulfed cell corpses are degraded.10-12

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a lysosome-mediated “self-eating” process which is highly conserved from yeast to human (for a review, see refs. 13 and 14). More than 30 autophagy genes regulate the multistep autophagy process, and the deregulation of autophagy has been linked to a variety of diseases including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.13 The initiation of autophagy involves the formation of autophagosomes, double-membraned vacuoles surrounding the intracellular materials targeted for degradation, including damaged organelles, protein aggregates and intracellular pathogens. Autophagosomes eventually fuse with lysosomes, resulting in the acidification and degradation of their contents. The process of autophagy produces ATP and metabolic precursors such as amino acids and fatty acids, which allows cells to maintain nutrient and energy homeostasis, and thereby enhances survival during stress. Besides autophagy, components of the autophagy machinery may participate in other membrane-trafficking events, including endocytosis and endocytic trafficking, phagocytosis, secretion and the recruitment of GTPases and other signaling molecules to intracellular membranes.15-23

There are several lines of evidence indicating that the autophagy pathway, or at least certain autophagy proteins, contribute to efficient apoptotic corpse clearance, either by generating “eat-me” signals in dying cells or through a role in the phagocytosis of apoptotic corpses. Qu et al.24 demonstrated defective PS exposure on dying cells and defective apoptotic corpse clearance in mammalian embryoid bodies lacking either Becn1 or Atg5. Mellen et al.25,26 demonstrated defective PS exposure on dying cells and defective apoptotic corpse clearance in chick embryo retinas treated with the autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine. Martinez et al.27 have shown that the autophagy genes, BECN1, ATG5 and ATG7, but not ULK1, are required for the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages, whereas Konishi et al.28 found that only BECN1, and neither ATG5 nor ULK1, are required for macrophage engulfment of apoptotic cells. In C. elegans, Ruck et al.29 demonstrated a role for the C. elegans orthologs of VPS30/ATG6/BECN1, ATG18 and ULK1 (bec-1, atg-18, unc-51, respectively) in germ cell corpse clearance in the adult gonad, and Li et al.30 demonstrated a role for the C. elegans autophagy genes, lgg-1 (ortholog of ATG8/MAP1LC3A/LC3), atg-18 and epg-5, but not unc-51, in Q cell neuroblast corpse clearance in the L1 larval stage.

These studies suggest that autophagy proteins may be crucial for apoptotic corpse clearance during programmed cell death. However, no previous studies have directly examined whether autophagy proteins are essential for apoptotic corpse clearance during embryonic development. Of note, Takacs-Vellai et al.31 reported that a null mutation in the autophagy gene, bec-1, increased the number of apoptotic cell corpses in C. elegans embryos. These results were hypothesized to reflect increased caspase-dependent apoptosis in the setting of BEC-1 deficiency. An open question is whether defects in apoptotic corpse engulfment may also contribute to increased apoptotic corpse numbers in bec-1-null C. elegans embryos. In addition, it is unknown whether the phenotype of increased corpses in C. elegans is specific to mutation of bec-1, a gene that has multiple functions in membrane trafficking16,17 and that encodes a protein which interacts with the antiapoptotic protein, CED-9/BCL2,32 or whether this phenotype is also observed in other autophagy mutant nematodes.

To address these questions, we analyzed cell corpse numbers and the kinetics of cell corpse clearance in C. elegans embryos with mutations in autophagy genes that act at different stages in the autophagy pathway. Together, our results suggest that autophagy genes are important for efficient apoptotic corpse clearance during C. elegans embryonic development by a mechanism that is genetically distinct from the ced-1, ced-6, ced-7, dyn-1 and the ced-2, ced-5, ced-12 engulfment pathways.

Results

Increased numbers of apoptotic cell corpses are detected in C. elegans embryos with mutations in autophagy genes

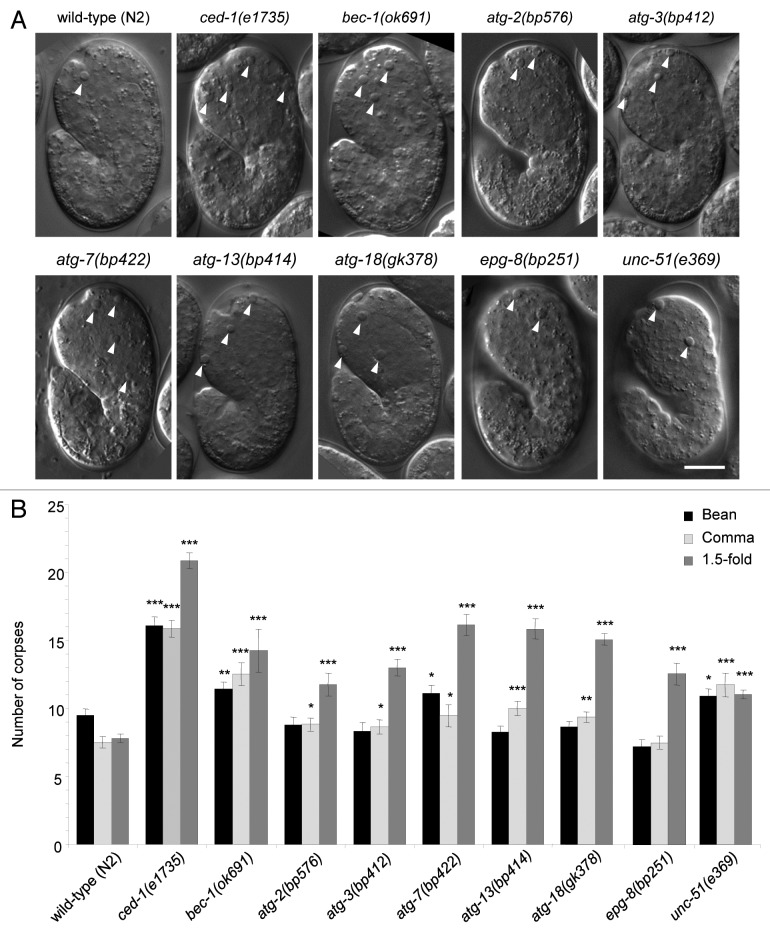

In C. elegans, 113 apoptotic cell corpses are generated during embryogenesis.33 These cell corpses show a distinct highly refractile, “button-like” appearance under Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. To investigate whether other autophagy genes play roles in apoptosis similar to that previously described for bec-1,31 we used DIC microscopy to determine the numbers of apoptotic cell corpses detected during C. elegans embryogenesis in eight strains with loss-of-function mutations in autophagy. We focused on three morphologically distinct embryonic developmental stages including bean, comma and 1.5-fold stages, that correspond to ~320 min, ~380 min and ~420 min after the first cleavage, respectively.34 We included analyses of the wild-type (N2) strain, and a well-studied engulfment mutant, ced-1(e1735),5,7,35 as controls. The eight autophagy-deficient strains included nematodes with mutations in two genes, atg-13 and unc-51, that are part of the serine/threonine kinase induction complex;36 two genes, bec-1 and epg-8 (which shares low similarity with mammalian ATG14),37 that are part of the class III PtdIns3-kinase complex involved in vesicle nucleation;36 two genes, atg-3 and atg-7, that are part of the protein conjugation system involved in ATG8/LC3 lipidation and vesicle expansion and completion;36 and two genes, atg-2 and atg-18, that are important for the recycling of autophagy machinery from mature autophagosomes.36

We found that, compared with wild-type embryos, all autophagy mutant strains examined had significantly more cell corpses at the 1.5-fold stage (Fig. 1A and B). Some strains also had increased numbers of cell corpses detected at the bean [bec-1(ok691), atg-7(bp412), unc-51(e369)] or comma [bec-1(ok691), atg-2(bp576), atg-3(bp412), atg-7(bp422), atg-13(bp414), atg-18(gk378), unc-51(e369)] stages. As these genes function in different steps of the autophagy pathway, these results suggest that the autophagy pathway, rather than potential autophagy-independent functions of individual autophagy genes, regulates apoptotic cell corpse number during C. elegans embryogenesis.

Figure 1. Detection of increased numbers of cell corpses in autophagy-mutant strains during C. elegans embryogenesis. (A) Representative DIC images and (B) quantification of numbers of apoptotic corpses in indicated C. elegans genotype, as detected by DIC microscopic analysis of the head region during bean, comma and 1.5-fold stages of embryogenesis. Wild-type (N2) and the engulfment mutant ced-1(e1735) strains were included for comparison. Arrowheads denote representative apoptotic corpses. Scale bar: 10 μm. Bar graph shows mean ± s.e.m. from at least 20 embryos for each genotype at each stage. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. wild-type embryos at the same stage of development; t-test.

Among the autophagy mutant alleles tested, only bec-1(ok691) animals are maintained as heterozygotes due to developmental and fertility defects in homozygous animals. Therefore, bec-1(ok691) homozygous embryos from heterozygous adults are expected to carry a maternal supply of the bec-1 gene product. To further deplete the maternal bec-1 gene product, a strain was constructed in which the homozygous bec-1(ok691) animals were kept alive and fertile by an extrachromosomal array expressing a functional BEC-1::mRFP transgene.38 Since the expression of the repetitive extrachromosomal array is repressed in the C. elegans germline,39,40 and the arrays are randomly lost during meiosis,41 the mRFP(-) embryos therefore lack both maternal and zygotic bec-1. We found that bec-1(ok691)(m−z−) (m, maternal gene product; z, zygotic gene product) embryos had a more striking increase in the number of cell corpses detected than bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) embryos as compared with wild-type animals [Fig. S1A; p < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA analysis for comparison of magnitude of increase in bec-1(ok691)(m−z−) embryos vs. in bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) embryos for both bean and comma stages]. Thus, the analysis of bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) animals may underestimate the physiological consequences of complete loss of bec-1 gene function. However, bec-1(ok691)(m−z−) animals displayed a more severe developmental defect than those of bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) animals; many bec-1(ok691)(m−z−) embryos were developmentally arrested prior to the bean stage, making it difficult to perform more detailed analyses in this strain. Therefore, subsequent experiments using bec-1(ok691) were performed with bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) embryos.

Delayed clearance of apoptotic cell corpses in autophagy mutant embryos

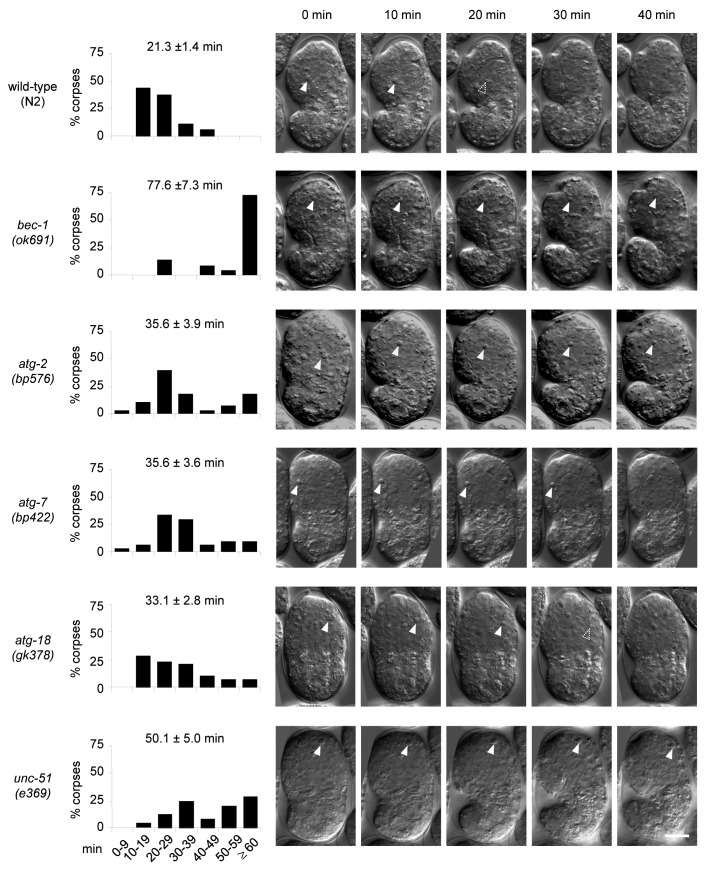

The observation of increased numbers of cell corpses during development may be due to increased cell death events, delayed cell corpse removal or both. To investigate whether the removal of cell corpses was delayed in autophagy mutant animals, we performed time-lapse DIC microscopy to analyze the duration of apoptotic cell corpse persistence. We analyzed at least one representative mutant strain for each group of autophagy genes (i.e., induction, vesicle nucleation, vesicle expansion/completion and recycling). In wild-type embryos, apoptotic cell corpses persisted an average of 21.3 ± 1.4 min, with less than 6% of the cell corpses persisting more than 40 min and no corpses persisting for more than 50 min (Fig. 2). The autophagy mutant embryos, bec-1(ok691), atg-2(bp576), atg-7(bp422), atg-18(gk378) and unc-51(e369) all showed notable delays in apoptotic cell corpse clearance, with corpses that persist for more than 60 min (Fig. 2). The magnitude of delay varied in different mutants; the most severe defect was observed in bec-1(ok691) embryos, with nearly 75% of corpses persisting more than 60 min. These kinetic analyses demonstrate that several different autophagy genes are required for efficient apoptotic corpse clearance during embryonic development.

Figure 2. Defective clearance of cell corpses in C. elegans autophagy-mutant strains. Histogram distributions of the duration of cell corpse persistence as observed by time-lapse DIC microscopy. The y-axis represents the percentages of cell corpses that persist within the specified duration range indicated on the x-axis. The numbers on top of each histogram indicate the mean duration (± s.e.m.). More than 22 corpses from more than five embryos were randomly chosen and followed for each genotype. DIC micrographs show apoptotic corpses (indicated by the arrowheads) in 10 min intervals from the appearance of a corpse (0 min) to 40 min. Scale bar: 10 μm.

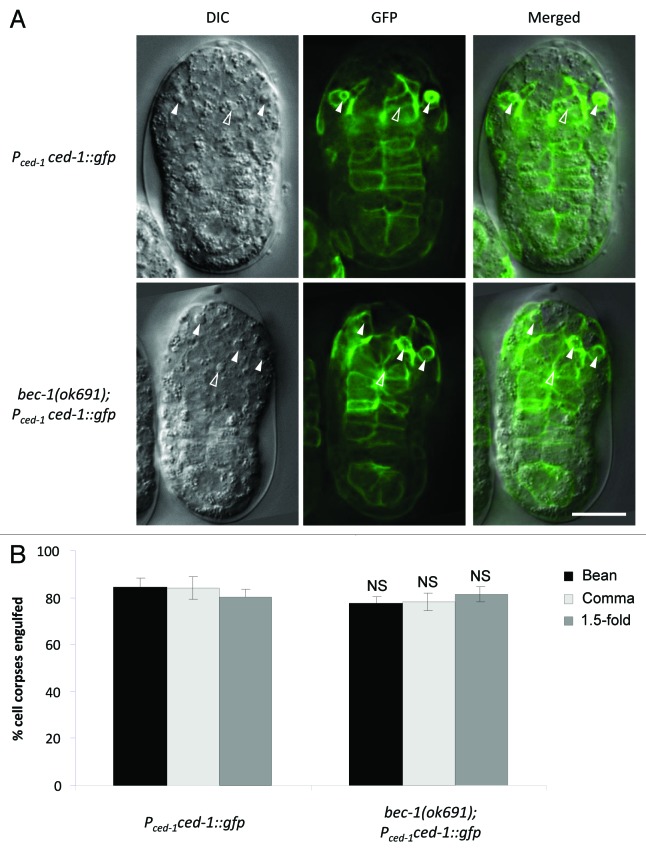

To determine whether the delay in cell corpse clearance is due to a defect in engulfment or in the degradation of engulfed cell corpses, we monitored the localization of the reporter Pced-1ced-1::gfp. CED-1 is a key cell surface receptor important for engulfment, and cell corpse engulfment can be detected by observing CED-1::GFP surrounding cell corpses in engulfing cells that express CED-1::GFP.35 Similar percentages of cell corpses were engulfed in bec-1(ok691) embryos as compared with wild-type controls during the bean, comma and 1.5-fold stages (Fig. 3). Thus, in bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) animals, delayed corpse clearance appears to be due to defects in the degradation of engulfed cell corpses, rather than defects in phagocytosis. However, bec-1(ok691)(m−z−) embryos showed a significant defect in corpse engulfment (Fig. S1B). Therefore, bec-1 may play roles in both cell corpse engulfment and in the degradation of engulfed cell corpses.

Figure 3. Engulfment of cell corpses in bec-1(ok691) mutant embryos. (A) Representative micrographs showing the expression of CED-1::GFP epifluorescence (middle) with the corresponding DIC (left) and merged (right) images in wild-type (upper panel) and bec-1(ok691) (lower panel) embryos at the bean stage. Pced-1 was used to drive the expression of CED-1::GFP. Solid arrowheads denote engulfed cell corpses detected by the presence of CED-1::GFP surrounding the corpse and CED-1::GFP-expression in the engulfing cell. Open arrowheads denote cell corpses that are not surrounded by CED-1::GFP. (B) Quantification of apoptotic cell corpses engulfed detected using the CED-1::GFP marker during bean and comma stages of embryogenesis. Bar graph shows mean ± s.e.m. for at least 10 embryos for each genotype at each stage. NS, not significant; t-test. Scale bars: 10 μm.

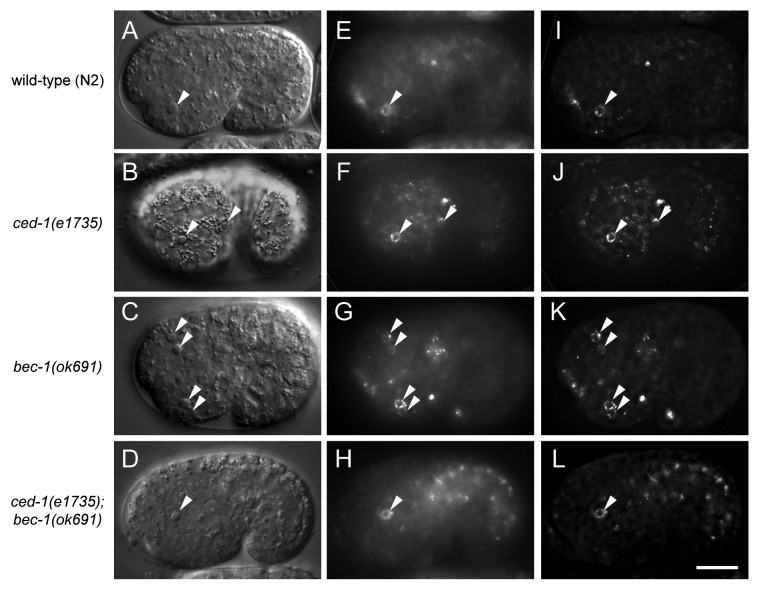

The autophagy gene bec-1 is not required for the exposure of PS in C. elegans embryos

In previous reports, autophagy gene mutation or pharmacological inhibition of autophagy resulted in PS exposure defects and persistent apoptotic cell corpses in developing mouse embryoid bodies24 and chick retina.25 However, in another study, autophagy inhibition did not block PS exposure in dying cells in the chick optic nerve or in later stages of retinal development.26 To determine whether autophagy is required for PS exposure on apoptotic corpses in live C. elegans embryos, we expressed GFP-labeled human Annexin V under the control of the dyn-1 promoter, which drives ubiquitous expression in embryos.7 Annexin V is a protein which binds to PS and is commonly used to detect PS exposure on the surface of apoptotic cells. The SEL-1 signal peptide domain was added to the N-terminus of GFP::Annexin V to promote the secretion of the fusion protein.42 Since bec-1(ok691) mutants showed the most severe cell corpse clearance defect (Figs. 1 and 2), we compared GFP::Annexin V fluorescence in the embryos of wild-type N2, ced-1(e1735), bec-1(ok691) animals and ced-1(e1735); bec-1(ok691) animals (Fig. 4). In the wild-type and the engulfment mutant ced-1(e1735) animals, GFP::Annexin V was highly enriched around apoptotic cell corpses with the GFP::Annexin V signal forming a ring-like structure decorated with aggregated puncta (Fig. 4E and F). The localization of GFP::Annexin V in vivo was better visualized after deconvolution of the epifluorescence images removing the optic distortion using a point spread function (Fig. 4I and J). Similar GFP::Annexin V rings were also detected around apoptotic cell corpses in bec-1(ok1691) and ced-1(e1735); bec-1(ok691) embryos (Fig. 4G, H, K and L). Thus, these results demonstrate that bec-1 is not required for PS exposure in dying cells during C. elegans development.

Figure 4. Lack of requirement for bec-1 in the exposure of phosphatidylserine in C. elegans corpses. Representative DIC images (A–D), the corresponding epifluorescence images (E–H), and the corresponding deconvolution images (I–L) showing cell corpses labeled with GFP::Annexin V in vivo in the indicated C. elegans genotype. GFP::Annexin V expression was driven by the dyn-1 promoter as an integrated transgene. Arrows denote corpses labeled with GFP::Annexin V rings. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Partial rescue of the persistent cell corpse phenotype in bec-1(ok691) embryos by expression of bec-1 under the control of the ced-1 promoter but not the egl-1 promoter

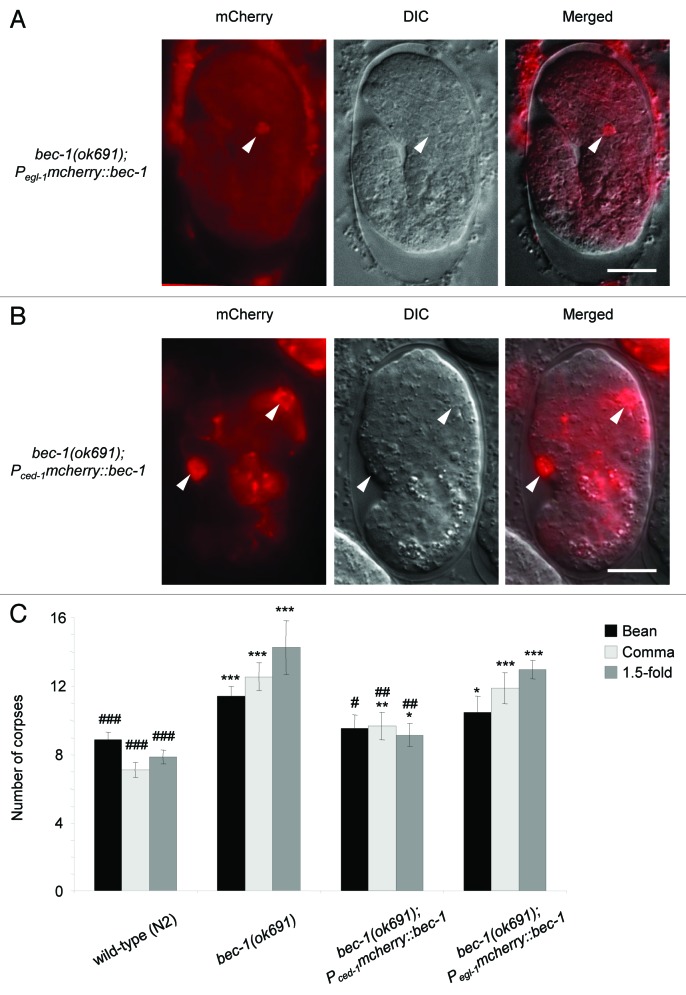

The lack of a defect in PS exposure in apoptotic corpses in bec-1(ok691) embryos suggested that autophagy in the dying cell may not be essential to generate engulfment signals, and rather, that the requirement for autophagy genes in the timely degradation of apoptotic corpses in C. elegans embryogenesis may instead reflect the recently described function of components of the autophagy machinery in the removal of apoptotic corpses by phagocytic cells. To evaluate this hypothesis, we determined whether the corpse clearance defect of bec-1(ok691) animals could be rescued by expressing bec-1 full-length cDNA under the control of the egl-1 promoter, which is active in apoptotic corpses,35,43 and/or by expressing bec-1 full-length cDNA under the control of the ced-1 promoter, which is active in healthy cells capable of engulfment.35 In both cases, we monitored the expression constructs by fusing an mCherry moiety to the N-terminus of BEC-1 (Fig. 5A and B).

Figure 5. Partial rescue of corpse clearance defect of bec-1(ok691) mutant animals by ced-1 promoter-driven expression of bec-1, but not egl-1 promoter-driven expression of bec-1. (A) Representative immunofluorescence micrographs showing the expression of Pegl-1 mcherry::bec-1 (left) with the corresponding DIC (middle) and merged (right) images in a bec-1(ok691). The embryo was stained with anti-dsRed antibodies. (B) Representative micrographs of Pced-1 mcherry::bec-1 expression in a bec-1(ok691) embryo. mCherry fluorescence is shown in the left panel, with the corresponding DIC image in the middle, and merged image in the right panel. For (A and B), arrowheads denote representative cells with MCHERRY::BEC-1 expression. (C) Quantification of apoptotic corpse numbers detected by DIC microscopy in the head region during bean, comma and 1.5-fold stages of embryogenesis. Bar graph shows mean ± s.e.m. for at least 20 embryos for each genotype at each stage. Pced-1 was used to drive the expression of N′ mCherry-fused bec-1 full-length cDNA in cells capable of engulfment. Pegl-1 was used to drive the expression of mcherry::bec-1 in cells undergoing apoptosis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 represent statistical comparison vs. wild-type embryos and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 represent statistical comparison vs. bec-1(ok691) embryos; t-test. Scale bars: 10 μm.

We confirmed that Pegl-1mcherry::bec-1 led to the expression of mCherry::BEC-1 exclusively in dying cells (Fig. 5A). This is predicted as EGL-1 is a BH3 domain protein that functions as an upstream activator of apoptosis, and its expression is detected only in cells undergoing apoptosis.35,43 Consistent with the lack of a defect in PS exposure in bec-1 (ok691) embryos, we found that the expression of bec-1 driven by the egl-1 promoter in apoptotic cells failed to reduce the number of cell corpses in bec-1(ok691) embryos (Fig. 5C). Together, these results suggest that bec-1 expression does not play a significant role in the dying cell to mediate apoptotic corpse clearance during C. elegans embryonic development.

In contrast, the expression of mCherry::BEC-1 under the control of the ced-1 promoter (which is widely used to drive transgene expression in engulfing cells35) resulted in nearly complete rescue of the corpse clearance defect in bec-1(ok691) embryos (Fig. 4C). The incomplete rescue may be due to different strength of expression from the transgene compared with the endogenous promoter and/or to the mosaic inheritance of the transgene. Although we occasionally detected the expression of Pced-1mcherry::bec-1 in apoptotic cell corpses, the number of mCherry-positive corpses was too small to account for the magnitude of the rescue by the transgene. Taken together with our findings of a lack of corpse clearance defect rescue in embryos with egl-1 promoter-driven expression of mCherry::BEC-1, these data indicate that BEC-1 expression in engulfing cells is essential for efficient apoptotic corpse clearance.

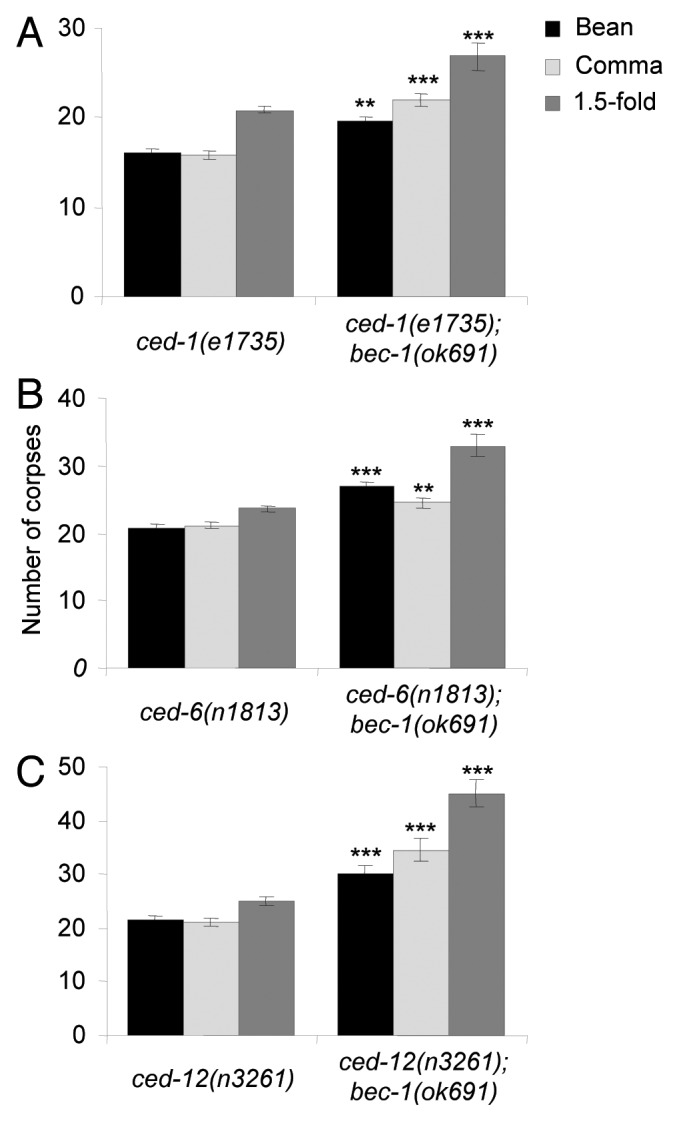

Enhancement of corpse clearance defects in engulfment mutants, ced-1(e1735), ced-6(n1813) and ced-12(n3261) by bec-1(ok691).

Our results above indicate that bec-1 functions in apoptotic corpse clearance during C. elegans embryogenesis. Therefore, we investigated whether bec-1 functions with or in parallel to two pathways that have been previously shown to be required for apoptotic corpse removal in C. elegans, the ced-1, ced-6, ced-7, dyn-1 pathway and the ced-2, ced-5, ced-12 pathway. Because the bec-1 gene is located on chromosome IV, we performed genetic epistasis analysis by generating double mutants of bec-1(ok691) with strong loss-of-function alleles of known engulfment genes that are not on the same chromosome, including ced-1, ced-6 and ced-12.35,44,45

We found that the number of cell corpses detected in ced-1(e1735), ced-6(n1813) or ced-12(n3261) single mutants (Fig. 6A–C) was greater than that observed in bec-1 single mutants (see Fig. 1). Of note, double mutants of bec-1(ok691) with ced-1(e1735), ced-6(n1813) or ced-12(n3261), all showed further increases in the numbers of cell corpses detected at bean, comma, and 1.5-fold stages compared with the single ced-1(e1735), ced-6(n1813) or ced-12(n3261) mutant (Fig. 6A–C). These results suggest that bec-1 does not function through the ced-1, ced-6 and ced-7 pathway nor through the ced-2, ced-5 and ced-12 pathway for corpse removal.

Figure 6. Enhancement of corpse clearance defects by bec-1(ok691) in engulfment mutants, ced-1(e1735) (A), ced-6(n1813) (B), and ced-12(n3261) (C). Bar graphs show mean ± s.e.m. at bean, comma, and 1.5-fold stages during embryogenesis. At least 20 embryos for each genotype were analyzed at each stage. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for comparison of double mutant on right vs. single mutant on left; t-test.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that several different autophagy gene mutant nematodes have increased embryonic corpses and delayed apoptotic corpse clearance. To our knowledge, these findings represent the first demonstration of a role for autophagy genes in apoptotic corpse clearance during embryonic development in an intact organism. These findings extend previous studies indicating a role for autophagy genes in corpse clearance in the C. elegans adult gonad29 and L1 larval stage Q cells.30 In contrast to results in mammalian embryoid bodies,24 an in vitro model for mammalian embryonic development, we did not find that autophagy genes were necessary for PS exposure in dying cells. Rather, our results are consistent with the emerging evidence that the autophagy machinery has a crucial function in mediating the efficient clearance of apoptotic corpses by phagocytes.27-30

The precise mechanism(s) by which autophagy genes mediate efficient apoptotic corpse clearance remain unclear. Other studies in autophagy-deficient mammalian macrophages27 and post-embryonic corpse clearance in C. elegans30 point to a defect in apoptotic corpse degradation, rather than uptake. For example, in C. elegans Q cell corpse clearance, the recruitment of phagosome/lysosome markers RAB5A, RAB7A and CTNS are delayed in two autophagy mutants, atg-18(gk378) and epg-5(tm3425),30 suggesting that autophagy plays a role in the degradation of engulfed cell corpses by regulating the process of phagosome maturation. This is consistent with studies that have demonstrated a role for certain autophagy proteins in phagolysosomal maturation in other biological contexts, including macrophage or dendritic cell engulfment of toll-like receptor ligands.15,27,46 Our study further supports the concept that the autophagy gene, bec-1, may function in the degradation of engulfed apoptotic corpses. Moreover, complete loss of both maternal and zygotic bec-1 also results in a defect in apoptotic corpse engulfment. Thus, autophagy genes may play roles in both apoptotic corpse engulfment and apoptotic corpse degradation during C. elegans embryogenesis.

The PIK3C3/VPS34-BECN1-containing class III PtdIns3P kinase complex plays a conserved role in apoptotic corpse removal in both mammalian cells27 and in C. elegans.29 This complex has autophagy-independent membrane trafficking functions, including a role in endocytosis,16,17 endocytic retrograde transport29 and LC3 recruitment to phagosomes;15 such functions may explain the more severe corpse clearance defect observed in our study in bec-1 vs. other autophagy gene mutant animals. In addition, BECN1 has been shown to interact with the mammalian ortholog of CED-10, the Rho GTPase, RAC1, and proposed to work in concert with RAC1 to coordinate actin dynamics and promote efficient apoptotic cell engulfment.28 It will be interesting to examine whether C. elegans BEC-1 interacts with CED-10 and is required for its function in C. elegans corpse removal; this possibility may also explain the more severe corpse clearance defect in bec-1 vs. other autophagy gene mutant nematodes.

Although the bec-1(ok691) corpse clearance delay phenotype was the most severe, we also observed corpse clearance defects in nematodes with mutations in other autophagy genes that are not part of the class III PtdIns 3-kinase complex, including atg-2, atg-7, atg-18 and unc-51. The differences in severity of corpse clearance defects may reflect differences in the underlying molecular basis of each mutant allele used (bec-1(ok691),29 atg-2(bp576) (Dr. Hong Zhang, personal communication), and atg-18(gk378)47 are predicted null alleles; unc-51(e369) is a strong loss-of-function allele;48 whereas atg-7(bp422) has a single amino acid change in the encoded protein that is predicted to affect protein activity);49 partial gene redundancy with homologs that are not detected by primary sequence similarities; and/or autophagy pathway-independent functions of the encoded autophagy protein. Nonetheless, the overlapping phenotypes in bec-1, atg-2, atg-7, atg-18 and unc-51 mutant animals provide strong genetic support that the autophagy pathway, rather than additional functions of autophagy genes, may be required for the proper removal of apoptotic cell corpses.

The role of unc-51, the C. elegans ortholog of Atg1/ULK1, in embryonic corpse clearance is noteworthy, as unc-51 and ULK1 were found to be dispensable for C. elegans Q cell corpse clearance and mammalian macrophage engulfment of apoptotic cells.28,30 However, our results are consistent with the previous report in C. elegans which found a role for unc-51 in germ cell corpse clearance in the adult gonad.29 It is not yet known whether unc-51/ULK1 truly functions in a cell-type or developmental stage-specific manner in apoptotic corpse clearance, or whether other factors may explain the contrasting findings in different studies. As UNC-51 and ULK1 are reportedly not involved in phagosomal maturation,29,30 the requirement for UNC-51 in efficient embryonic corpse clearance (the present study) and germ cell clearance in the adult gonad29 may be an important clue that the autophagy pathway contributes via other mechanisms to apoptotic corpse clearance in certain developmental contexts.

Our epistasis analyses indicate that bec-1 likely functions in parallel with the two cell corpse clearance pathways, the ced-1, ced-6, ced-7 and dyn-1 pathway, and ced-2, ced-5 and ced-12 pathway. It is possible that bec-1 is part of a third pathway that converges on ced-10, especially in view of the recently described interaction between the mammalian orthologs of BEC-1 and CED-10.28 Alternatively, bec-1 and other autophagy genes may function in parallel to ced-10 in promoting efficient apoptotic corpse clearance. Further genetic studies will be required to determine the precise relationships between bec-1 (and other autophagy genes) and the major known C. elegans engulfment pathways. Such studies should facilitate a deeper understanding of the molecular and cellular events that likely play a conserved role in apoptotic corpse clearance.

Materials and Methods

Strains and genetics

C. elegans strains were maintained at 23°C as described.50 All strains were grown on nematode growth media (NGM) plates and fed E. coli bacteria, strain DA837. C. elegans var Bristol strain N2 obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center was used as the wild-type reference. The following mutants were used: LGI (linkage group I), ced-1(e1735), ced-12(n3261), epg-8(bp251); LGIII (linkage group III), atg-13(bp414), ced-6(n2095); LGIV (linkage group IV), atg-3(bp412), atg-7(bp422), bec-1(ok691); LGV (linkage group V), atg-18(gk378), unc-51(e369), enIs35[Pced-1ced-1::gfp, Pced-12xFYVE::mRFP, unc-76(+)]; and LGX (linkage group X), atg-2(bp576). The balancer for LGIV; LGV, nT1[qIs51], was used to balance bec-1(ok691) mutants. The mutants atg-2(bp576), atg-3(bp412), atg-7(bp422), atg-13(bp414) and epg-8(bp251) were kindly provided by Dr. Hong Zhang (National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing, China). The extrachromosomal transgene enEx919[Pbec-1bec-1::mRFP] was introduced to rescued bec-1(ok691) to study the maternal effect of bec-1 in bec-1(ok691).

Microscopy and quantification

Live embryos were collected onto 3% agarose pads for imaging on a Zeiss Imager M2 microscope equipped with Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) and epifluorescence optics. Stack images with 0.8 μm between each slice were acquired with a CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera using Axiovision software (Zeiss). Apoptotic cell corpses were identified by their highly refractile appearance under DIC, and the corpses in the head region of embryos were scored at different developmental stages defined on the basis of the morphology of the embryos. Embryos that were developmentally arrested were excluded from analysis. For time-lapse imaging, embryos were mounted onto 3% agarose pads sealed with petroleum jelly. Stack DIC images with 0.8 μm between each slice were recorded at 2 min intervals for over 2 h to score the duration of apoptotic cell corpses. Less than five corpses were randomly chosen per embryo and > 22 corpses were analyzed for each genotype. p-values for pair-wise comparison were calculated using a t-test. For GFP::Annexin V and CED-1::GFP detection, deconvolution of Z-stack epifluorescence images was performed with AutoQuant software (Bitplane) using a blind deconvolution algorithm (20 iterations, medium noise). Engulfment of cell corpses in bec-1(ok691)(m+z−) was analyzed by the detection of CED-1::GFP surrounding the cell corpses inside engulfing cells that express CED-1::GFP. Engulfment of cell corpses in bec-1(ok691)(m−z−) was analyzed using the Pced-1ced-1c::gfp reporter, which expresses the cytoplasmic fragment of CED-1 fused to GFP. Engulfed cell corpses were recognized as dark spheres surrounded by cytoplasmic CED-1c::GFP.

Plasmid construction and transgenic strains

For Pced-1mcherry::bec-1, a full-length bec-1 cDNA fragment with N-terminal SalI-BamHI sites and a C-terminal KpnI site was cloned into the SalI and KpnI sites of pZZ954, which contains a 5.1 kb ced-1 promoter and the unc-54 3′UTR. To visualize expression of the construct, a SalI-mcherry-BamHI fragment was cloned into the resulting plasmid to create Pced-1mcherry::bec-1. Pced-1mcherry::bec-1 was maintained as extrachromosomal arrays generated by microinjection into bec-1(ok691)/nT1[qIs51] together with the dominant roller marker pRF4 [rol-6(su1006)]. Embryos negative for nT1[qIs51] GFP and positive for mCherry were used to quantify the number of apoptotic cell corpses.

For Pegl-1mcherry::bec-1, a full-length bec-1 cDNA fragment was inserted between the BamHI-AgeI sites of pZZ609, which contains a 1 kb egl-1 promoter and a 5.6 kb egl-1 3′UTR. mCherry was cloned into the BamHI site upstream of bec-1 to create Pegl-1mcherry::bec-1. The plasmid containing Pegl-1mcherry::bec-1 was injected into bec-1(ok691)/nT1[qIs51] together with the dominant roller injection marker pRF4 [rol-6(su1006)] to generate extrachromosomal transgenic lines. The extrachromosomal arrays were integrated by irradiation followed by five outcrosses. Expression of the transgene was confirmed by RT-PCR and immunostaining. For immunofluorescence staining, the embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, freeze-cracked and treated with dimethylformamide (DMF, Sigma-Aldrich Corp., D4551). The embryos were stained with anti-dsRed antibodies (rabbit, 1:100 in PBS, Clontech 632496) and labeled with goat-anti-rabbit AlexaFluor594 (donkey, 1:250 in PBS, Invitrogen A21207). After five outcrosses, live embryos negative for nT1[qIs51] GFP were used to quantify the number of apoptotic cell corpses.

For Pdyn-1sel-1sp::gfp::annexinV, a 3.2 kb dyn-1 promoter was cloned to drive expression of gfp::annexinV in the L754 vector. An 85 amino acid sel-1 signal peptide was amplified from pSZ8 (gift of Dr. Michael O. Hengartner, University of Zurich, Switzerland) and inserted into the N-terminus of gfp::annexinV to facilitate secretion of the protein. The plasmid containing Pdyn-1sel-1sp::gfp::annexinV was injected into ced-1(e1735) together with the dominant roller injection marker pRF4 [rol-6(su1006)] to generate extrachromosomal transgenic lines. The extrachromosomal arrays were integrated by irradiation followed by five outcrosses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Hong Zhang, Dr. Michael O. Hengartner, and Dr. Bruce Bamber for providing nematode strains and reagents, and Dr. Katherine Luby-Phelps and Mr. Abhijit Bugde in the UTSW Live Cell Imaging Core for assistance with microscopy. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). The work in the authors’ laboratory was funded by NIH awards RO1 CA109618 (B.L.) and GM067848 (Z.Z.); and an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholars Award in Aging (K.J.)

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- bec-1

C. elegans ortholog of yeast VPS30/mammalian BECN1

- BH3

BCL2 homology 3

- C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- lgg-1

C. elegans ortholog of yeast ATG8/mammalian MAP1LC3A

- mRFP

monomeric red fluorescent protein

- PS

phosphatidylserine, PtdIns3-kinases, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/22352

References

- 1.Elliott MR, Ravichandran KS. Clearance of apoptotic cells: implications in health and disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:1059–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickman G, Julian L, Olson MF. How apoptotic cells aid in the removal of their own cold dead bodies. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:735–42. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Y, Tibrewal N, Birge RB. Phosphatidylserine recognition by phagocytes: a view to a kill. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregory CD, Pound JD. Cell death in the neighbourhood: direct microenvironmental effects of apoptosis in normal and neoplastic tissues. J Pathol. 2011;223:177–94. doi: 10.1002/path.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddien PW, Horvitz HR. The engulfment process of programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:193–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.022003.114619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lettre G, Hengartner MO. Developmental apoptosis in C. elegans: a complex CEDnario. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrm1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu X, Odera S, Chuang CH, Lu N, Zhou Z. C. elegans Dynamin mediates the signaling of phagocytic receptor CED-1 for the engulfment and degradation of apoptotic cells. Dev Cell. 2006;10:743–57. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu X, Lu N, Zhou Z. Phagocytic receptor CED-1 initiates a signaling pathway for degrading engulfed apoptotic cells. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinchen JM, Cabello J, Klingele D, Wong K, Feichtinger R, Schnabel H, et al. Two pathways converge at CED-10 to mediate actin rearrangement and corpse removal in C. elegans. Nature. 2005;434:93–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Z, Yu X. Phagosome maturation during the removal of apoptotic cells: receptors lead the way. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:474–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinchen JM, Doukoumetzidis K, Almendinger J, Stergiou L, Tosello-Trampont A, Sifri CD, et al. A pathway for phagosome maturation during engulfment of apoptotic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:556–66. doi: 10.1038/ncb1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu N, Zhou Z. Membrane trafficking and phagosome maturation during the clearance of apoptotic cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012;293:269–309. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394304-0.00013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanjuan MA, Dillon CP, Tait SW, Moshiach S, Dorsey F, Connell S, et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450:1253–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He C, Levine B. The Beclin 1 interactome. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thoresen SB, Pedersen NM, Liestøl K, Stenmark H. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase class III sub-complex containing VPS15, VPS34, Beclin 1, UVRAG and BIF-1 regulates cytokinesis and degradative endocytic traffic. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3368–78. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mariño G, Fernández AF, Cabrera S, Lundberg YW, Cabanillas R, Rodríguez F, et al. Autophagy is essential for mouse sense of balance. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2331–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI42601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–35. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris J. Autophagy and cytokines. Cytokine. 2011;56:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupont N, Jiang S, Pilli M, Ornatowski W, Bhattacharya D, Deretic V. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J. 2011;30:4701–11. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeSelm CJ, Miller BC, Zou W, Beatty WL, van Meel E, Takahata Y, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate the secretory component of osteoclastic bone resorption. Dev Cell. 2011;21:966–74. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chua CE, Lim YS, Lee MG, Tang BL. Non-classical membrane trafficking processes galore. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:3722–30. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu X, Zou Z, Sun Q, Luby-Phelps K, Cheng P, Hogan RN, et al. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell. 2007;128:931–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellén MA, de la Rosa EJ, Boya P. The autophagic machinery is necessary for removal of cell corpses from the developing retinal neuroepithelium. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1279–90. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellén MA, de la Rosa EJ, Boya P. Autophagy is not universally required for phosphatidyl-serine exposure and apoptotic cell engulfment during neural development. Autophagy. 2009;5:964–72. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez J, Almendinger J, Oberst A, Ness R, Dillon CP, Fitzgerald P, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (LC3)-associated phagocytosis is required for the efficient clearance of dead cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17396–401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113421108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Konishi A, Arakawa S, Yue Z, Shimizu S. Involvement of Beclin 1 in engulfment of apoptotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13919–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.348375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruck A, Attonito J, Garces KT, Núnez L, Palmisano NJ, Rubel Z, et al. The Atg6/Vps30/Beclin 1 ortholog BEC-1 mediates endocytic retrograde transport in addition to autophagy in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2011;7:386–400. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.4.14391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W, Zou W, Yang Y, Chai Y, Chen B, Cheng S, et al. Autophagy genes function sequentially to promote apoptotic cell corpse degradation in the engulfing cell. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:27–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takacs-Vellai K, Vellai T, Puoti A, Passannante M, Wicky C, Streit A, et al. Inactivation of the autophagy gene bec-1 triggers apoptotic cell death in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1513–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conradt B, Xue D. Programmed cell death. WormBook. 2005;6:1–13. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.32.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu N, Yu X, He X, Zhou Z. Detecting apoptotic cells and monitoring their clearance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;559:357–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-017-5_25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Z, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. CED-1 is a transmembrane receptor that mediates cell corpse engulfment in C. elegans. Cell. 2001;104:43–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meléndez A, Levine B. Autophagy in C. elegans. WormBook. 2009:1–26. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.147.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang P, Zhang H. The coiled-coil domain protein EPG-8 plays an essential role in the autophagy pathway in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2011;7:159–65. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.2.14223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowland AM, Richmond JE, Olsen JG, Hall DH, Bamber BA. Presynaptic terminals independently regulate synaptic clustering and autophagy of GABAA receptors in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1711–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly WG, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Fire A. Distinct requirements for somatic and germline expression of a generally expressed Caernorhabditis elegans gene. Genetics. 1997;146:227–38. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly WG, Fire A. Chromatin silencing and the maintenance of a functional germline in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1998;125:2451–6. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin Y. Transformaion. In: Hope IA, ed. C. elegans: A practical approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999:69-96. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Züllig S, Neukomm LJ, Jovanovic M, Charette SJ, Lyssenko NN, Halleck MS, et al. Aminophospholipid translocase TAT-1 promotes phosphatidylserine exposure during C. elegans apoptosis. Curr Biol. 2007;17:994–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The TRA-1A sex determination protein of C. elegans regulates sexually dimorphic cell deaths by repressing the egl-1 cell death activator gene. Cell. 1999;98:317–27. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu QA, Hengartner MO. Human CED-6 encodes a functional homologue of the Caenorhabditis elegans engulfment protein CED-6. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1347–50. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Z, Caron E, Hartwieg E, Hall A, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans PH domain protein CED-12 regulates cytoskeletal reorganization via a Rho/Rac GTPase signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2001;1:477–89. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee HK, Mattei LM, Steinberg BE, Alberts P, Lee YH, Chervonsky A, et al. In vivo requirement for Atg5 in antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;32:227–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borsos É, Erdélyi P, Vellai T. Autophagy and apoptosis are redundantly required for C. elegans embryogenesis. Autophagy. 2011;7:557–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.5.14685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogura K, Wicky C, Magnenat L, Tobler H, Mori I, Müller F, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2389–400. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Yan L, Zhou Z, Yang P, Tian E, Zhang K, et al. SEPA-1 mediates the specific recognition and degradation of P granule components by autophagy in C. elegans. Cell. 2009;136:308–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. 2006;11:1–11. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.