Abstract

Introduction

To compare the diagnostic values of three-dimensional sonohysterography (3DSH), transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), and 2-dimensional sonohysterography (2DSH) in the work-up of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), in particular the ability of each method to identify intracavitary lesions arising from the endometrium or uterine wall.

Materials and methods

24 patients referred for AUB underwent TVUS followed by 2-D and 3-D HS in the same session. Three-dimensional data were acquired with a free-hand technique during maximal distention of the uterus. Within 10 days of the sonographic session, each patient underwent hysteroscopy, which was considered the reference standard. For each of the 3 imaging methods, we calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy.

Results

Hysteroscopy demonstrated the presence of an intrauterine lesion in 21/24 patients (87.5%). In 3/24 patients hysteroscopy was negative. For TVUS, 2DSH, and 3DSH, sensitivity was 76% (16/21), 90% (19/21), 100% (21/21), respectively; specificity was 100% (3/3), 100% (19/19), 100% (21/21); PPV was 100%, 100%, 100%; NPV was 37%, 60%, 100%; accuracy was 76%, 90%, 100%.

Conclusions

3DSH is more sensitive that 2DSH or TVUS in the detection of intrauterine lesions. If these preliminary results are confirmed in larger studies, 3DSH could be proposed as a valuable alternative to diagnostic hysteroscopy.

Keywords: Sonohysterography, Three-dimensional sonohysterography, Hysteroscopy, Abnormal uterine bleeding

Sommario

Introduzione

Valutare l'impatto diagnostico della Isterosonografia Tridimensionale (ISG 3D) nello studio della cavità uterina in donne con sanguinamento anomalo (SUA) rispetto all'ecografia transvaginale (ETV) e all'isterosonografia bidimensionale (ISG 2D), particolarmente per l'identificazione di neoformazioni a sviluppo endocavitario della superficie endometriale e della parete uterina.

Materiali e metodi

Ventiquattro pazienti affette da SUA sono state incluse nello studio. Ciascuna di esse é stata sottoposta ad ETV, ISG e ISG 3D durante la medesima seduta. Le acquisizioni 3D sono state ottenute con tecnica free-hand in fase di massima replezione idrica della cavità. Tutte le pazienti sono state valutate con isteroscopia entro 10 giorni dall'ecografia. Considerando l'esame isteroscopico come reference standard, sono stati calcolati i valori di sensibilità, specificità, valore predittivo positivo (VPP), valore predittivo negativo (VPN) ed accuratezza delle tre metodiche.

Risultati

L'isteroscopia ha dimostrato la presenza di lesioni endocavitarie in 21/24 pazienti (87,5%). Nelle restanti pazienti l'esame isteroscopico è risultato negativo. ETV, ISG 2D ed ISG 3D hanno mostrato rispettivamente sensibilità del 76% (16/21), 90% (19/21), 100% (21/21); specificità del 100% (3/3), 100% (19/19), 100% (21/21); VPP del 100%, 100%, 100%; VPN del 37%, 60%, 100%; accuratezza 76%, 90%, 100%. L'ISG 3D ha consentito una completa identificazione dei rapporti delle lesioni con la cavità uterina e con la parete endometriale.

Conclusioni

L'ISG 3D è una metodica con maggiore sensibilità nella definizione delle lesioni della cavità uterina rispetto all'ISG 2D ed all'ETV. Se questi dati preliminari saranno confermati da studi piú ampi, ISG 3D potrebbe essere proposta come alternativa all'isteroscopia eseguita a soli fini diagnostici.

Introduction

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is a fairly common complaint among reproductive-aged and post-menopausal women. In most cases AUB is caused by hormonal disorders, but it can also be an indirect sign of other more or less serious conditions, such as endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, or malignant lesions of the cervix or endometrium [1]. In both pre- and post-menopausal women, the causes of these episodes are usually benign. Consequently, it is important to identify a relatively noninvasive, low-cost method that can reliably differentiate between cases that require surgical intervention and those that are related to hormonal or functional conditions.

Hysteroscopy is performed by introducing a fiberoptic endoscope into the uterine cavity after the induction of general anesthesia. Although this approach is fairly invasive and expensive, it is considered a reference standard for identifying uterine lesions associated with AUB because it allows direct visualization and biopsy of the lesion, which are mandatory for its correct identification [2,3]. Other techniques for the assessment of the uterine cavity include transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS), conventional (or 2-dimensional [2D]) sonohysterography (2DSH), and three-dimensional sonohysterography (3DSH). TVUS is currently considered a first-level examination in the work-up of AUB. It is well tolerated, noninvasive, and relatively inexpensive, and it provides adequate information on the thickness and homogeneity of the endometrium and the presence of gross focal lesions [4]. In some cases, however, TVUS is not reliable for identifying the nature of the lesions seen (benign proliferation, hyperplasia, polyps, neoplasia) [5,6]. An additional limitation of this method is that it frequently misses certain types of lesions, including tiny polyps or other small lesions [7–9] and submucosal leiomyomas [10].

2DSH is currently indicated when TVUS fails to identify the cause of uterine bleeding or when it reveals an abnormality of the uterine cavity that cannot be reliably characterized [11]. 2DSH involves injection of several milliliters of saline into the uterine cavity during TVUS, which distends the walls of the organ and thus facilitates the detection of focal endometrial lesions. For this reason, 2DSH is better suited than TVUS for exploration of the uterine cavity [12–14]. It is also minimally invasive and low-cost, and it is virtually free of major complications [15].

Some studies [16–19] have found that 3DSH offers even better visualization of the endometrium and more accurate assessment of the uterine cavity, as well as improved visualization of uterine anatomy, which is particularly useful in cases of congenital anomalies [20]. Data for 3-dimensional elaboration can be acquired with a mechanical transducer. Another option involves the use of a free-hand technique with a conventional 2-D transducer. The data can then be re-elaborated with special software. The 3D re-elaboration requires only a few seconds to reconstruct the entire volume of the uterine walls and cavity.

The aim of the present study was to compare the diagnostic impact of 3DSH with that of TVUS and 2DSH in the work-up of patients with AUB, in particular its ability to identify intracavitary neoformations on the endometrial surface or the uterine wall.

Materials and methods

After obtaining ethical committee approval, we enrolled 24 patients with AUB who had been referred to the radiology service of our hospital. Candidates were excluded if they had genital infections or known or suspected cervical carcinoma. All participants provided informed consent to all study procedures.

The uterus of each patient was examined with TVUS and 2DSH and 3DSH (all performed during a single session). The images were recorded on the hard disk of the computer and later subjected to double-blinded assessment by a radiologist and a gynecologist. All three examinations were performed with an iU22 scanner (Koninklijke Philips Electronics, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) and a transvaginal transducer (8–4 MHz). With TVUS, the uterus was examined in the sagittal and axial planes. A sterile vaginal speculum was used for the SH examinations. After disinfection with a 10% solution of povidone–iodine (Surgical Betadine, Meda Pharma, Italy), a SH balloon catheter (5.5 F, GTA Medical Device, Imperia, Italy) was inserted in the uterine cervix, the balloon was inflated, and the uterine cavity was filled with saline solution until the cavity was well distended and the endometrial wall could be well visualized. During the 2-D examination, the uterine cavity was examined in the axial and sagittal planes. The 3D examination was carried out with a free-hand technique during maximum distention of the uterus. Within 10 days after the sonographic examinations, each patient was evaluated with hysteroscopy.

Statistical analysis

For each of the 3 sonographic techniques, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) in the identification of uterine lesions and compared the results with those obtained with hysteroscopy (reference standard).

Results

Hysteroscopy revealed intracavitary lesions in 21/24 patients (87.5%) (Figs. 1–5). In the other patients, the examination was negative, and the AUB was attributed to hormonal dysfunction. TVUS revealed intracavitary lesions in 16 of the hysteroscopy-positive cases (sensitivity 76% (16/21), specificity 100% (3/3), PPV 100% (16/16), NPV 37% (3/8), accuracy 76% (16/21)).

Fig. 1.

Septate uterus with a polyp in one hemicavity. (a) Transvaginal ultrasound: sagittal scan of the uterine body. (b) 2-D sonohysterography: the intracavitary polyp is clearly visualized (arrow). (c) 3-D sonohysterography: multiplane reconstruction. Visualization in the coronal plane allows precise assessment of the septum (S) and polyp (arrow) in one of the hemicavities.

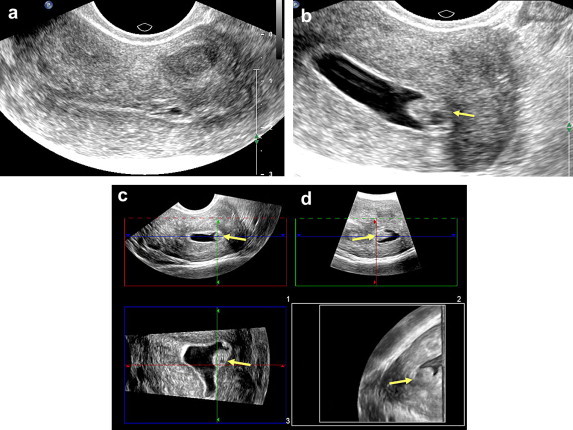

Fig. 2.

Sessile polyp arising from the left wall. (a) Transvaginal ultrasonography provides inadequate visualization of the lesion. (b) 2-D sonohysterography provides good visualization of the intracavitary polyp (arrow). (c) 3-D sonohysterography with multiplane reconstruction and (d) 3-D sonohysterography with volumetric reconstruction: coronal scan of the cavity provides precise information on the polyp's attachment to the juxta-tubal endometrium (arrow).

Fig. 3.

Congenital malformation. (a) 2-D sonohysterography: The axial section suggests the presence of a fundus defect (arrow). (b) 3-D sonohysterography with multiplane reconstruction reveals an arcuate (or saddle-shaped) uterus (arrow).

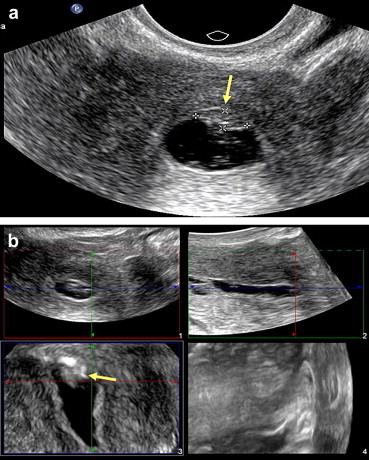

Fig. 4.

Assessment of the uterine fundus. (a) 2-D sonohysterography: Axial scan of the uterus reveals evidence suggestive of a small lesion in the fundus (arrow). (b) 2-D sonohysterography: the fundus lesion is clearly visualized (arrow). The irregular appearance of the wall is caused by peristalsis.

Fig. 5.

Value of coronal-plane scans. (a) A polyp located in the tubal angle can be fully explored on the coronal scan (arrow). (b) A submucosal myoma (associated with menometrorrhagia) can be seen protruding into the cavity of uterus. The fundus malformation can be seen better on the coronal reconstruction (arrow).

2DSH displayed 100% specificity (19/19), 90% sensitivity (19/21), PPV and NPV of 100% (19/19) and 60% (3/5), respectively, and 90% accuracy (19/21).

In all 21 of the hysteroscopy-positive cases, 3DSH detected lesions arising from the endometrial or myometrial wall and protruding into the uterine cavity (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy – all 100%). In these patients, 3DSH clearly depicted the lesions' relation with the uterine cavity and endometrial wall.

Discussion

Our experience shows the 3DSH is more sensitive than TVUS or 2DSH in detecting and characterizing lesions arising from the endometrial or myometrial wall that protrude into the uterine cavity. Diagnostic hysteroscopy with biopsy (if needed) is currently considered the reference standard for the work-up of patients with AUB [2]. However, it is invasive and expensive, and it is associated with serious complications like perforation of the uterus and infections of the genitourinary tract [3]. Alternative diagnostic procedures include TVUS, 2DSH, and 3DSH.

In our study, TVUS showed the poorest performance in the detection of protruding endometrial or myometrial lesions. In fact, although this approach offered high specificity and a 100% PPV – comparable to those for diagnostic hysteroscopy – it was associated with lower sensitivity (76%) and PPV (37%), which reflected its failure to detect wall anomalies in 5 of the hysteroscopy-positive cases. These figures can probably be attributed to the limited capacity of this method to identify peripheral and isthmal lesions in nondistended uteri and to detect small lesions protruding into the uterine cavity when the endometrium is thickened, hyperechoic, and heterogeneous. As previously demonstrated, assessments of the uterine cavity based exclusively on the thickness of the endometrium will not reveal small lesions. When the uterus is not distended, these lesions are compressed and flattened, and they adapt to the shape of the endometrial cavity [8,13]. TVUS did not provide adequate definition of the anatomic relations between detected lesions and the uterine cavity and/or endometrium. In our study, TVUS yielded false-negative results in 5 of the 21 cases with protruding endometrial or myometrial lesions identified by hysteroscopy. Therefore, negative TVUS findings cannot be considered reliable and should be verified with other diagnostic procedures.

As for 2DSH, this method not only equaled TVUS in terms of specificity and PPV (100%), it offered higher sensitivity, NPV, and accuracy (90%, 60%, and 90%, respectively). This method identified 19/21 intracavitary lesions and/or endometrial wall lesions, compared with the 16/21 detected by TVUS. These results can probably be attributed to the fact that sonographic examination of the distended uterus allows better visualization of the endometrial wall and more effective detection of any anomalies that may be present, as demonstrated in previous studies [1,2,9–20]. This improved visualization is associated with better definition of the lesions' anatomic relations with the uterine cavity and myometrium. Indeed, some studies have concluded that 2DSH is also useful in the preoperative work-up of certain lesions [21]. They demonstrated that 2DSH is an optimal method for evaluating the magnitude of the protrusion, the angle between the mass and the endometrium, and the extension of the protruding lesion within the myometrium [21]. Its use is therefore recommended in cases of AUB in which TVUS yields negative results [1]. The images obtained with 2DSH can be re-elaborated to obtain 3-dimensional reconstructions.

In our study, 3DSH displayed 100% sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy in identifying focal lesions, values that are comparable to those of the reference method (hysteroscopy), and it correctly detected the lesions in the 2 cases that produced false-negative results in 2DSH. The performance of 3DSH was not only statistically superior to that of 2DSH in detecting the lesions, it also provided better anatomic definition of these lesions thanks to the use of coronal-plane scans, which cannot be obtained with the 2-D technique.

These observations are in line with the results obtained in other studies, which demonstrate the superiority of 3DSH over 2DSH in defining the relations between intracavitary lesions and the endometrium and also the degree of myometrial involvement [16,17,21]. According to these studies, in fact, evaluation of the uterus in three different planes allows correct definition of the volume of the lesion, which cannot be measured with precision during a 2-dimensional examination. 3DSH also allowed us to identify an arcuate uterus that was missed with the other techniques we tested in this study. On the basis of our findings, 3DSH can therefore be considered a valid alternative to diagnostic hysteroscopy in the work-up of patients with AUB. In any case, definitive diagnosis requires histological analysis of the suspicious lesion [22]. The NiGo technique has recently been proposed for use in these cases: it allows one to collect biopsy material during 2DSH, without having to resort to hysteroscopy [23].

Three-dimensional re-elaboration of the data obtained with 2DSH can provide reconstruction of the entire volume of the uterus (walls and cavity) within only a few seconds. The information obtained from 3-D reconstruction of the uterine volume could theoretically improve the accuracy of an examination based on the NiGo technique plus 2DSH.

The main limitation of our study is the small number of patients examined. In any case, this number seems to be an indicator of the applicational potential of 2DSH. In addition, the positive cases identified with TVUS may have biased the SH examinations, which were performed immediately after TVUS. This condition certainly influenced the statistical parameters for the SH technique.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 3DSH might represent a new standard for characterizing AUB: it is relatively noninvasive and associated with virtually no serious complications, but its diagnostic capacity is comparable to that of hysteroscopy. However, prospective, randomized studies on larger groups of patients are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Miller J.C., Schiff I., Thrall J.H., Lee S.I. Ultrasound and sonohysterography in the evaluation of abnormal vaginal bleeding. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5(11):1154–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Kroon C.D., de Bock G.H., Dieben S.W., Jansen F.W. Saline contrast hysterosonography in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2003;110(10):938–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.02472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indman P.D. Hysteroscopic complications. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;3:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)80131-8. (editorial) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubinsky T.J. Value of sonography in the diagnosis of abnormal vaginal bleeding. J Clin Ultrasound. 2004;32(7):348–353. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullinan J.A., Fleischer A.C., Kepple D.M., Arnold A.L. Sonohysterography: a technique for endometrial evaluation. Radiographics. 1995;15(3):501–516. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.3.7624559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubinsky T.J., Parvey H.R., Gormaz G., Curtis M., Maklad N. Transvaginal hysterosonography: comparison with biopsy in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14(12):887–893. doi: 10.7863/jum.1995.14.12.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronz L., Suter T., Rusca T. The value of transvaginal sonography with and without saline instillation in the diagnosis of uterine pathology in pre- and post-menopausal women with abnormal bleeding or suspect sonographic findings. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9(1):53–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.09010053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emanuel M.H., Verdel M.J., Wamsteker K., Lammes F.B. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasonography and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: clinical applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(2 Pt1):547–552. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dijkhuizen F.P., Brolmann H.A., Potters A.E., Bongers M.Y., Heinz A.P. The accuracy of transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of endometrial abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(3):345–349. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarzler P., Concin H., Bösch H. An evaluation of sonohysterography and diagnostic hysteroscopy for the assessment of intrauterine pathology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11(5):337–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.11050337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sylvestre C., Child T.J., Tulandi T., Tan S.L. A prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of two- and three-dimensional sonohysterography in women with intrauterine lesions. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(5):1222–1225. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yildizhan B., Yildizhan R., Ozkesici B., Suer N. Transvaginal ultrasonography and saline infusion sonohysterography for the detection of intra-uterine lesions in pre- and post-menopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Int Med Res. 2008;36(6):1205–1213. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laifer-Narin S., Ragavendra N., Parmenter E.K., Grant E.G. False-normal appearance of the endometrium on conventional transvaginal sonography: comparison with saline hysterosonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(1):129–133. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares S.R., Barbosa dos Reis M.M., Camargos A.F. Diagnostic accuracy of sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography and hysterosalpingography in patients with uterine cavity diseases. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(2):406–411. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernard J.P., Metzger U., Rizk E., Jeffry L., Camatte S., Taurelle R. Hysterosonography. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2002;30(11):882–889. doi: 10.1016/s1297-9589(02)00460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonilla-Musoles F., Raga F., Osborne N.G., Blanes J., Coelho F. Three-dimensional hysterosonography for the study of endometrial tumors: comparison with conventional transvaginal sonography, hysterosalpingography, and hysteroscopy. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65(2):245–252. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonilla-Musoles F., Raga F., Blanes J., Osborne N.G., Coelho F. Three dimensional hysterosonographic evaluation of the normal endometrium: comparison with transvaginal sonography and three dimensional ultrasound. J Gynecol Surg. 1997;13:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Torre R., De Felice C., De Angelis C., Coacci F., Mastrone M., Cosmi E.V. Transvaginal sonographic evaluation of endometrial polyps: a comparison with two-dimensional and three- dimensional contrast sonography. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1999;26(3–4):171–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radoncic E., Fnduk-Kurjac B. Three dimensional ultrasound for routine check-up in in vitro fertilization patients. Croat Med J. 2000;41(3):262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leone F.P., Lanzani C., Ferazzi E. Use of strict sonohysterographic methods for preoperative assessment of submucous myomas. Fertil Steril. 2002;79(4):998–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04916-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salim R., Lee C., Davies A., Jolaoso B., Ofuasia E., Jurkovic D. A comparative study of three-dimensional saline infusion sonohysterography and diagnostic hysteroscopy for the classification of submucous fibroids. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):253–257. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohan S., Page L.M., Higham J.M. Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21(6):891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicoletti L., Gorlero F., Lijoi D., Nicoletti A., Lorenzi P., Ragni N. A new technique to obtain endometrial directed biopsy during sonohysterography: the NiGo device. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(6):505–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]