Abstract

Background

Clinical and preclinical data demonstrate the analgesic actions of adenosine. Central administration of adenosine agonists, however, suppresses arousal and breathing by poorly understood mechanisms. This study tested the two-tailed hypothesis that adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation (PRF) of C57BL/6J mice modulate breathing, behavioral arousal, and PRF acetylcholine release.

Methods

Three sets of experiments used 51 mice. First, breathing was measured by plethysmography after PRF microinjection of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) or saline. Second, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and time to recovery of righting response (RoRR) was quantified after PRF microinjection of SPA or saline. Third, acetylcholine release in the PRF was measured before and during microdialysis delivery of SPA, the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX), or SPA and DPCPX.

Results

First, SPA significantly decreased respiratory rate (−18%), tidal volume (−12%) and minute ventilation (−16%). Second, SPA concentration accounted for 76% of the variance in RoRR. Third, SPA concentration accounted for a significant amount of the variance in acetylcholine release (52%), RoRR (98%), and breathing rate (86%). DPCPX alone caused a concentration-dependent increase in acetylcholine, decrease in RoRR, and decrease in breathing rate. Coadministration of SPA and DPCPX blocked the SPA-induced decrease in acetylcholine and increase in RoRR.

Conclusions

Endogenous adenosine acting at adenosine A1 receptors in the PRF modulates breathing, behavioral arousal, and acetylcholine release. The results support the interpretation that an adenosinergic-cholinergic interaction within the PRF comprises one neurochemical mechanism underlying the wakefulness stimulus for breathing.

Introduction

ADENOSINE has particular relevance for anesthesiology due to the good agreement between preclinical and clinical data that adenosine can provide nonnarcotic analgesia (reviewed in1,2). Long-standing evidence that the adenosine antagonist caffeine promotes wakefulness3,4 prompted the more recent findings that adenosine promotes sleep (reviewed in5) and that opioid-induced decreases in brain levels of adenosine contribute to sleep disruption caused by opioids.6,7 The neuronal networks, neurotransmitters, and receptor systems by which adenosine alters behavioral arousal and control of breathing remain incompletely understood.

An extensive neuronal network and multiple neurotransmitters, including adenosine and acetylcholine, regulate the loss of wakefulness during anesthesia8 and sleep.9 For example, cholinergic neurotransmission in the pontine reticular formation promotes arousal10 and adenosine alters arousal, in part, by inhibiting cholinergic neurons11 that provide acetylcholine to the pontine reticular formation.12 Enhancing cholinergic neurotransmission in the pontine reticular formation causes a significant decrease in the release of acetylcholine within frontal association cortex,13 the rodent homologue of primate prefrontal cortex.14,15 The discovery that activating adenosine receptors in the prefrontal cortex of mouse decreases acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation16 encourages efforts to better understand the functional significance of adenosinergic signaling in the pontine reticular formation. Therefore, the present experiments were designed to test the two-tailed hypothesis that adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J (B6) mouse modulate breathing, behavioral arousal, and acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation.

Materials and Methods

Three sets of experiments were performed using procedures described in detail previously.16–19 First, microinjection and whole body plethysmography were used to test the effects on breathing of activating adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation. Second, microinjections were made to determine whether administering an adenosine A1 receptor agonist directly into the pontine reticular formation modulates behavioral arousal by altering time to recovery of righting response after isoflurane anesthesia. Finally, microdialysis was performed to deliver an adenosine A1 receptor agonist and antagonist to the pontine reticular formation of anesthetized mouse while quantifying acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation, breathing rate, and time to resumption of righting after isoflurane anesthesia.

Animals and Drug Solutions

Protocols for animal experiments were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals and complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition (National Academy of Sciences Press, Washington, DC, 2011). Adult, male, B6 mice (n = 51; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in temperature and humidity controlled rooms with constant illumination and ad libitum access to food and water. Drugs delivered to the pontine reticular formation by microinjection or microdialysis included the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX; Sigma-Aldrich). A microinjection volume of 50 nL was delivered over a 1-min period. Salts for Ringer’s solution (147 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 4 mM KCl, 10 µM neostigmine) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Neostigmine bromide was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, as was dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Drug solutions for intracranial administration were prepared immediately prior to use. For microdialysis delivery, DPCPX was dissolved in DMSO and diluted in Ringer’s to a final DMSO concentration of 1.0%. SPA was dissolved in Ringer’s.

Implantation of Intracranial Guide Tubes for Microinjection Experiments

Briefly, mice (n = 12) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) delivered in 100% O2, then transferred to a Kopf Model 962 stereotaxic frame with a Kopf Model 923-B mouse anesthesia mask (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Delivered isoflurane concentration was decreased to 1.6% and measured continuously using a Cadiocap/5 monitor (Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, CO). Warm water was pumped through a heating pad (TP400 T/Pump Heat Therapy System, Gaymar, Orchard Park, NY) to maintain core body temperature at 37 °C. A craniotomy was made above the colliculi to enable access to the pontine reticular formation. One 26-gauge stainless steel guide tube occluded with a removable stylet (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) was aimed for stereotaxic coordinates 4.7 mm posterior to bregma, 0.7 mm lateral to midline, and 5 mm ventral to bregma.20 Dental acrylic (Jet Acrylic Self Curing Resin and Liquid, Lang Dental Manufacturing Company Inc., Wheeling, IL) was applied to hold the guide tube in place. Isoflurane delivery was then stopped and animals were observed until they were ambulatory. Mice were allowed to recover from surgery for 7 days before being used for experiments.

Behavioral Conditioning and Quantification of Breathing

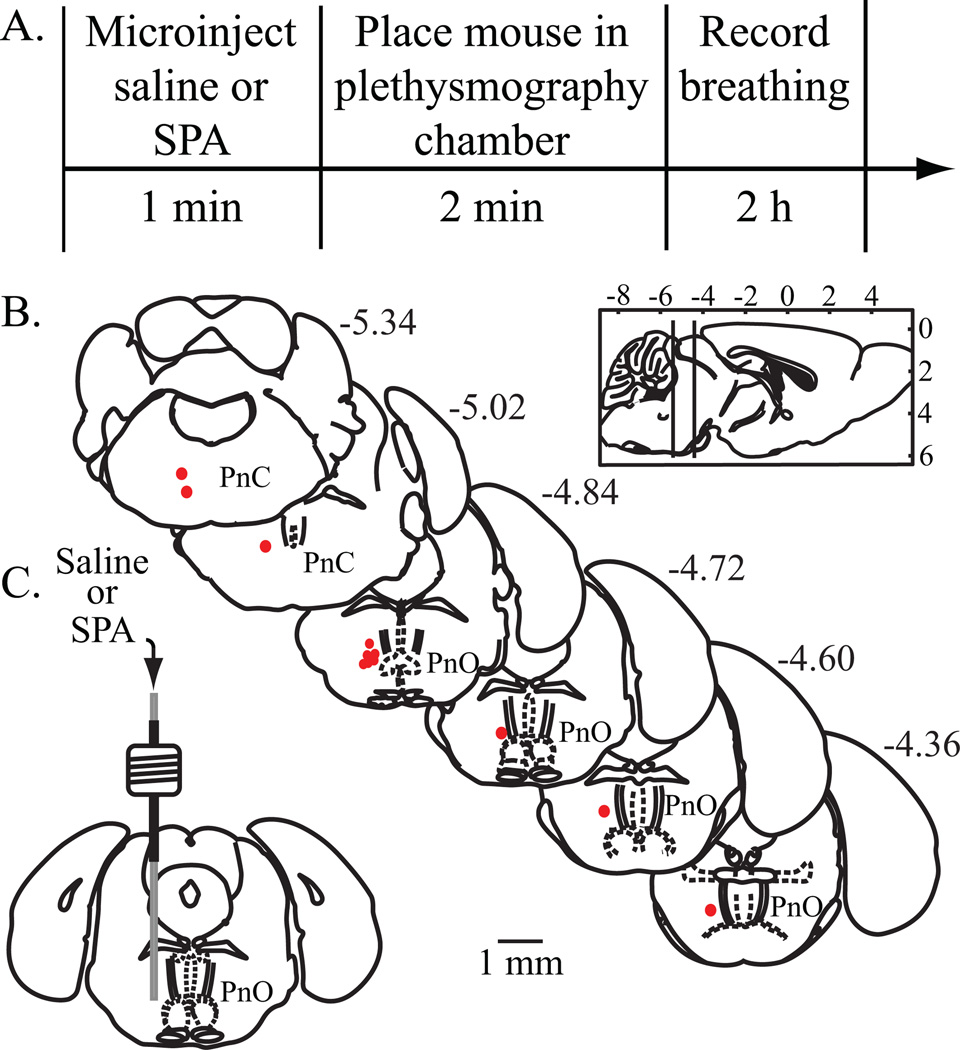

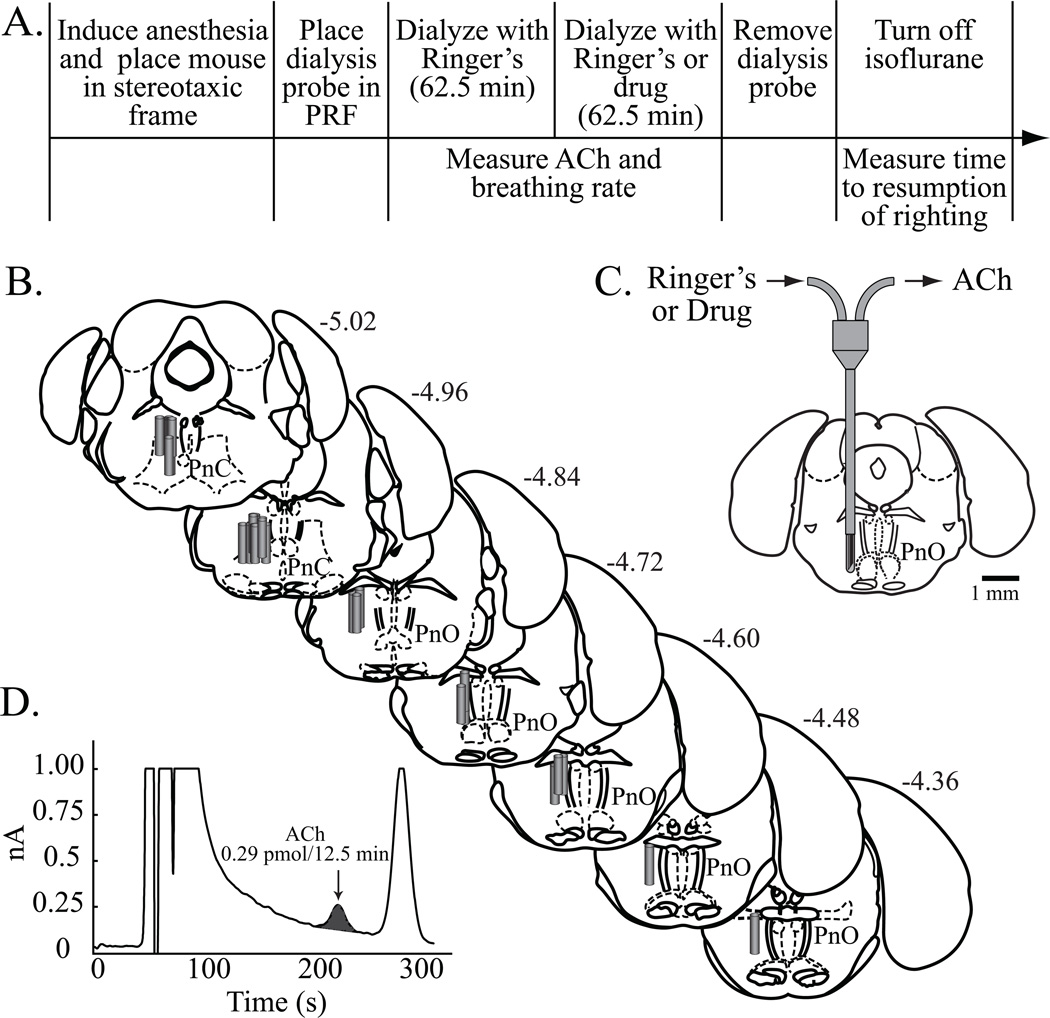

During the surgical recovery period, mice were conditioned to the testing procedures by daily handling and by being placed in a whole body plethysmography chamber for unrestrained mouse (PLY 3211; Buxco Electronics Inc., Troy, NY). A 2-h baseline recording of breathing was then obtained for each mouse. Microinjections were performed between 11:00 AM and 1:00 PM. A manual microdrive connected to a 31-gauge microinjector was used to deliver saline (vehicle control) or the selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA (8.8 pmol/50 nL, equivalent to 3.9 ng/50 nL). Every mouse received one microinjection each of saline and SPA, with a minimum of 3 days between microinjections in the same mouse. As schematized by figure 1A, immediately after the microinjection mice were placed in pre-calibrated, temperature controlled (26–28°C) plethysmography chambers. Dependent measures of breathing were obtained in 5-min bins for 2 h, yielding a total of 24 bins per mouse.

Figure 1.

Study design for obtaining plethysmographic measures of breathing, and results from histological localization of microinjection sites. Sagittal and coronal schematics were modified from a mouse brain atlas.18 (A) The top row summarizes the sequence of procedures used to quantify the effects of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) on breathing. The bottom row reports the amount of time required for each procedure. (B) Filled red circles indicate the microinjection sites. All sites were localized to the oral (PnO) and caudal (PnC) pontine reticular nuclei, which comprise the pontine reticular formation. The numbers shown at the top right of each coronal drawing correspond to the distance (mm) posterior to bregma. The sagittal schematic of the mouse brain has vertical lines that delineate the anterior-to-posterior range of microinjection sites. (C) The coronal diagram illustrates a permanently implanted guide tube containing a removable microinjection cannula in the PnO.

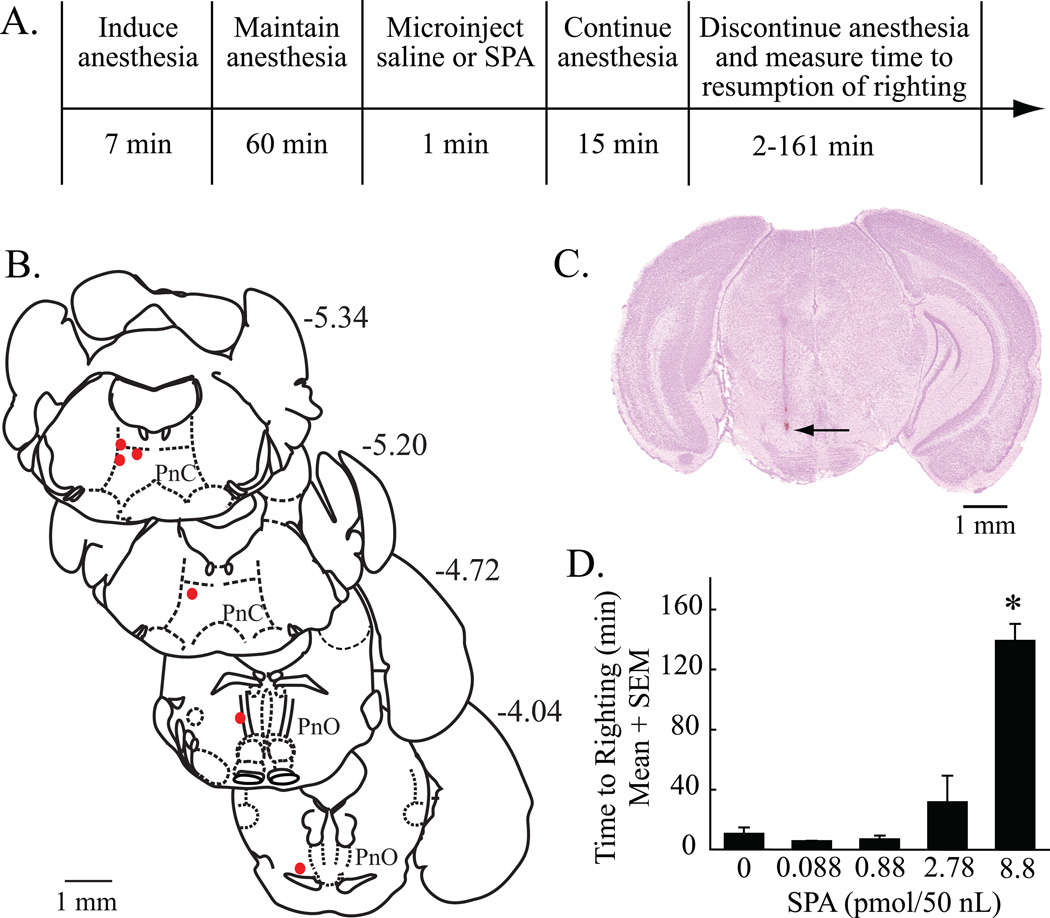

Measurement of Time to Resumption of Righting after Anesthesia

Mice (n = 6) were implanted with a guide tube as described above and experiments began after the 7-day recovery period. Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in 100% O2 delivered for 7 min. Anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% isoflurane for 60 min, then saline or SPA (0.088, 0.88, 2.78, or 8.8 pmol/50 nL, equivalent to 0.039, 0.39, 1.239, or 3.9 ng/50 nL, respectively) was microinjected into the pontine reticular formation. Anesthesia was continued for an additional 15 min, then isoflurane delivery was discontinued and mice were placed in dorsal recumbency on a heating pad. The time to righting and resumption of normal weight bearing posture was recorded. Time to resumption of righting is an established, surrogate measure of the time needed to regain wakefulness after discontinuing the delivery of an anesthetic drug.16,17,21

In Vivo Microdialysis and High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Electrochemical Detection

A third group of mice (n = 33) was anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in 100% O2, and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Monitoring procedures were the same as described above. A midline incision was made in the scalp, followed by a craniotomy at stereotaxic coordinates 4.7 mm posterior to bregma and 0.7 mm lateral to the midline.20 A CMA/7 dialysis probe (6 kDa cutoff; 1.0 mm length, 0.24 mm diameter cuprophane membrane; CMA/Microdialysis, North Chelmford, MA) was aimed for the pontine reticular formation. Delivered isoflurane concentration was reduced and maintained at 1.3%, which corresponds to the EC50 or minimum alveolar concentration (1 MAC) for B6 mouse.22

The microdialysis probe was perfused continuously (2 µL/min) with Ringer's solution (control). A CMA/110 liquid switch was used to change the dialysis solution from Ringer’s to Ringer’s containing drug. One dialysis sample (25 µL) was collected every 12.5 min. Control levels of acetylcholine release were determined during dialysis with Ringer’s prior to dialysis delivery of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 mM) and antagonist DPCPX (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 mM). Drugs were delivered for 62.5 min. As described in detail,16 approximately 5% of the drug concentration that is delivered to the dialysis probe is estimated to cross the dialysis membrane and enter the brain. Thus, drug concentrations that were tested for effects on the dependent measures are estimated to have ranged from 0.05 to 500 µM. Each mouse was used for only one microdialysis experiment, and only one concentration of the drug was tested per mouse. After the last dialysis sample was collected, the microdialysis probe was removed from the brain, the scalp incision was closed, and anesthesia was discontinued. Mice were removed from the stereotaxic frame and placed in dorsal recumbency under a heat lamp. Temperature under the heat lamp was maintained between 28 and 32°C. The time (min) required for resumption of righting was recorded.

Dialysis samples were injected offline into a high performance liquid chromatography system for electrochemical detection of acetylcholine (Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN). The amount of acetylcholine recovered by the microdialysis probe was tested before and after every experiment by placing the probe in an acetylcholine solution of known concentration. Data from an experiment were eliminated if a significant difference by t-test was seen between the pre- and postexperiment probe recoveries.

Histological Analysis of Microinjection and Microdialysis Sites

Mice were deeply anesthetized and decapitated 7 days after microdialysis experiments and 3 days after microinjection experiments. Brains were immediately removed and frozen, and coronal sections of 40 µm thickness were obtained. The sections were mounted serially on glass slides and fixed with hot paraformaldehyde vapor (80°C). The location of each microdialysis or microinjection site was determined by comparing the cresyl-violet stained sections with an atlas of the mouse brain.20 Results from an experiment were included in the group data only when histology confirmed that the microdialysis probe or microinjector had been placed in the pontine reticular formation.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were run using Prism 5 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, version 5.0d for MAC OS X). Dependent measures of breathing obtained by whole body plethysmography were analyzed by paired t-test, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures, and Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. The effects of microinjecting SPA into the pontine reticular formation on time to righting were tested by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Acetylcholine release was expressed as percent of mean acetylcholine measured during dialysis with Ringer’s (control condition). Drug main-effects on acetylcholine release, time to resumption of righting after anesthesia, and breathing rate during anesthesia were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test or Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. Nonlinear regression analysis was used to determine the amount of variability in acetylcholine release, anesthesia recovery time, and breathing rate accounted for by the concentration of SPA or DPCPX that was used for dialysis of the pontine reticular formation. Analyses were independently confirmed by the University of Michigan Center for Statistical Consultation and Research. Analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System v9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The regression approach used a general linear model in which dose was considered to have a linear effect while ignoring correlations among observations on the same mouse. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant effect.

Results

SPA Depressed Breathing

The first set of experiments (figs. 1–3) determined that microinjection of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA into the pontine reticular formation of awake mouse significantly depressed breathing. All microinjection sites were histologically confirmed to be in the pontine reticular formation (fig. 1B, C). Average stereotaxic coordinates for the 12 injection sites were 4.9 ± 0.08 mm posterior to bregma, 0.6 ± 0.03 mm lateral to the midline, and 4.7 ± 0.07 mm ventral to bregma.20

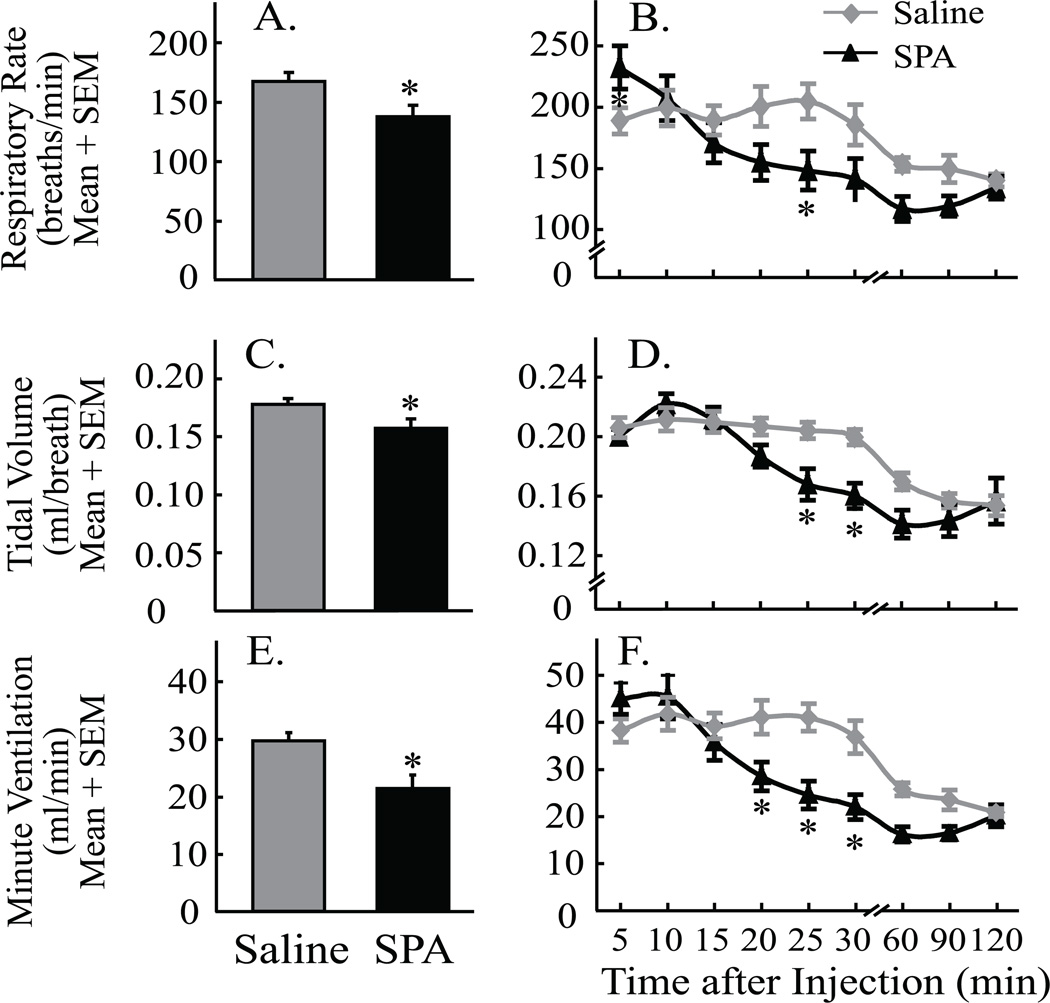

Figure 3.

Microinjection of N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) into the pontine reticular formation significantly depressed breathing. Graphs illustrate respiratory rate (A & B), tidal volume (C & D), and minute ventilation (E & F) quantified by plethysmography after microinjection of SPA and saline. Asterisks indicate a significant (P < 0.05) difference from saline (vehicle control). Data are from 12 mice.

Figure 2 shows representative traces of breathing recorded from a single, unrestrained B6 mouse. Compared to saline (control) injection (fig. 2A) breathing was markedly slowed within 5 min after microinjection of SPA (fig. 2B) and continued to decrease over the next 30 min (fig. 2C, D, and E). Figure 3 summarizes the group data from the plethysmographic studies of breathing. Figures 3A, C, and E plot measures of breathing averaged for 2 h after microinjection of SPA and saline into the pontine reticular formation. These data were analyzed by paired t-test. SPA significantly decreased respiratory rate (fig. 3A; t = 3.4; df = 11; P = 0.0028), tidal volume (fig. 3C, t = 3.4; df = 11; P = 0.0032), and minute ventilation (fig. 3E, t = 5.9; df = 11; P < 0.0001). In additional experiments, co-administration of DPCPX (100 µM) and SPA (8.8 mM) diminished the SPA-induced decrease in minute ventilation by 24%. Considered together, these findings of significant respiratory depression across a 2-h period justified a detailed time-course analysis of changes in breathing caused by SPA. Measures of breathing depicted at 9 time points after microinjection are plotted in figures 3B, D, and F. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparisons tests were used to analyze the data. For respiratory rate (fig. 3B) there was a significant main-effect of time after injection (F = 15.8; df = 8, 176; P < 0.0001) and time-by-drug interaction (F = 4.8; df = 8, 176; P < 0.0001). Post hoc analysis using Dunn’s multiple comparisons test revealed that SPA significantly decreased breathing rate at 25 min (P < 0.05) after microinjection into the pontine reticular formation. For tidal volume (fig. 3D) there was a significant main-effect of time after injection (F = 34.4; df = 8, 176; P < 0.0001) and a significant time-by-drug interaction (F = 4.4; df = 8, 176; P < 0.0001). SPA significantly decreased tidal volume at 25 min (P < 0.05) and 30 min (P < 0.01) after administration. Minute ventilation (fig. 3F) showed a significant main-effect of time after injection (F = 37.8; df = 8, 176; P < 0.0001), drug treatment (F = 4.2; df = 1, 176; P = 0.05), and a significant time-by-drug interaction (F = 7.6; df = 8, 176; P < 0.0001). SPA significantly decreased minute ventilation at 20 min (P < 0.05), 25 min (P < 0.001) and 30 min (P < 0.01) after microinjection.

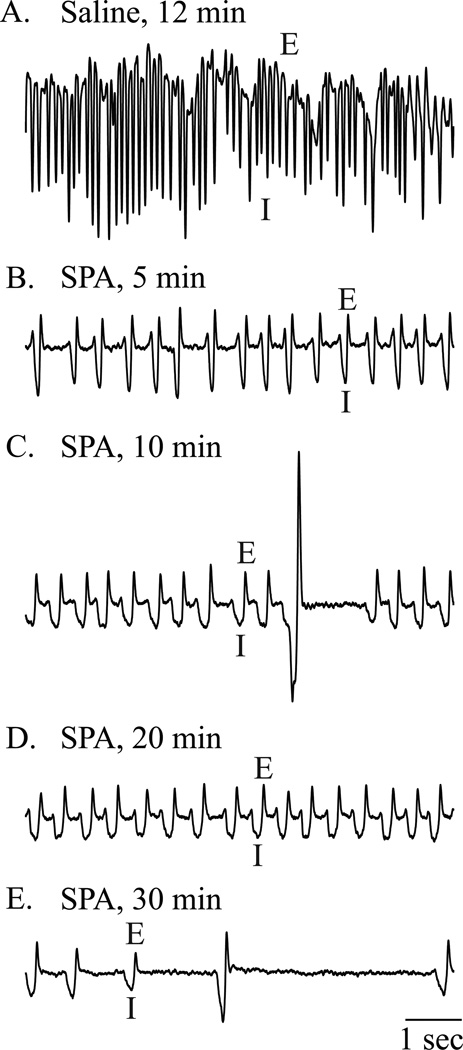

Figure 2.

Microinjection of N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) into the pontine reticular formation altered respiratory rhythm. Each of the five frames shows 8 s of recording from the same mouse obtained during one session in the plethysmography chamber. These recordings are representative of the group data. Breathing waveforms are labeled to indicate expiration (E) and inspiration (I). (A) Respiratory rate after microinjection of saline was about 170 breaths/min in this animal. (B-E) Breathing traces show decreasing respiratory rate across time (5, 10, 20, and 30 min after injection of SPA). (E) SPA caused irregular breathing and long periods of apnea.

SPA Delayed Resumption of Righting After Isoflurane Anesthesia

A second set of experiments in a separate group of mice was designed (fig. 4A) to determine whether microinjection of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA into the pontine reticular formation modulates behavioral arousal. Microinjection sites from the six mice used for this study were confirmed to be within the pontine reticular formation (fig. 4B and C). The average location of the injection sites was 5.0 ± 0.2 mm posterior to bregma, 0.7 ± 0.04 mm lateral to the midline, and 4. 6 ± 0.08 mm ventral to bregma.20 One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of SPA concentration on the time required for resumption of righting after discontinuation of isoflurane anesthesia (fig. 4D) (F = 22.1; df = 4, 22; P < 0.0001). Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test identified the 8.8 pmol/50 nL concentration of SPA as causing a significant increase in recovery time (P < 0.05). Nonlinear regression analysis showed that the concentration of SPA accounted for 76% of the variance in wake-up time after anesthesia.

Figure 4.

Microinjection of N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) into the pontine reticular formation increased time to resumption of righting following isoflurane anesthesia. (A) The top row outlines the sequence of experimental manipulations and the bottom row reports the time required for each procedure. (B) Filled red circles indicate the location of each microinjection site to the oral (PnO) and caudal (PnC) pontine reticular nuclei, which comprise the pontine reticular formation. Numbers shown at the top right of each drawing correspond to the distance (mm) posterior to bregma. (C) A cresyl-violet stained coronal section of mouse brainstem shows a representative microinjection site (arrow) in the PnO at approximately 4 mm posterior to bregma and 0.8 mm lateral to the midline. (D) Time to resumption of righting following isoflurane anesthesia was significantly increased after microinjection of SPA (8.8 pmol/50 nL). Data are from three trials per concentration of SPA. Each concentration of SPA was tested in at least three mice. Asterisk indicates a significant (P < 0.05) difference from saline (vehicle control, 0 pmol SPA).

Adenosine A1 Receptors in the Pontine Reticular Formation Modulate Acetylcholine Release and Behavioral Arousal

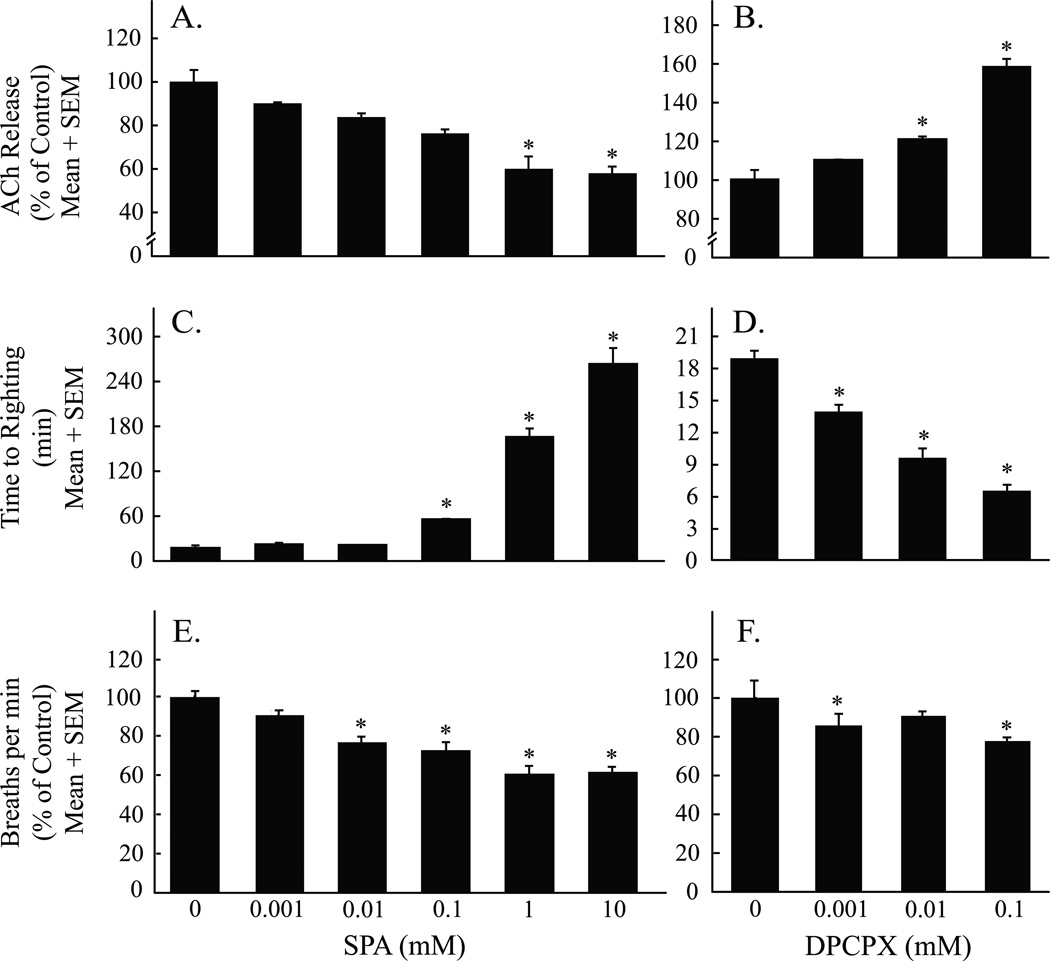

Figure 5A outlines the design used for the microdialysis studies. Figure 5B summarizes the results of the histological analysis, which confirmed that all 18 microdialysis sites from experiments using SPA were localized to the pontine reticular formation. Average stereotaxic coordinates were 4.9 ± 0.03 mm posterior to bregma, 4.8 ± 0.04 mm ventral to bregma, and 0.6 ± 0.04 mm lateral to the midline.20 These stereotaxic coordinates were used to place the microdialysis probe (fig. 5C) for drug delivery into the pontine reticular formation while simultaneously measuring acetylcholine release (fig. 5D). Figure 6A shows that dialysis administration of SPA to the pontine reticular formation caused a concentration-dependent decrease in acetylcholine release (F = 5.8; df = 5, 24; P < 0.0001) within the pontine reticular formation. Figure 6B shows that dialysis delivery of DPCPX to the pontine reticular formation caused a concentration-dependent increase in acetylcholine release (F = 16.9; df =3, 14; P < 0.0001). SPA (fig. 6C) caused a concentration-dependent increase in the time to resumption of righting after anesthesia (F = 110.1; df = 5, 12; P < 0.0001). In contrast, DPCPX (fig. 6D) caused a concentration-dependent decrease in time to resumption of righting after anesthesia (F = 74.1; df = 3, 8; P < 0.0001). SPA (fig. 6E) caused a concentration-dependent decrease in breathing rate (F = 25.2; df = 5, 12; P < 0.0001). DPCPX (fig. 6F) also caused a concentration-dependent decrease in breathing rate (F = 8.7; df = 3, 8; P = 0.007). Nonlinear regression analyses revealed that the concentration of SPA accounted for 52% of the variance in acetylcholine release, 98% of the variance in wake-up time, and 86% of the variance in breathing rate. Across all experiments there was no significant difference in the amount of time (min) that mice were exposed to isoflurane (i.e., total anesthesia time).

Figure 5.

Study design for obtaining measures of acetylcholine (ACh) release, and results from the histological localization of microdialysis sites. The coronal drawings of mouse brainstem were modified from a stereotaxic atlas.18 (A) The top row describes the time course of microdialysis in the pontine reticular formation (PRF). The bottom row indicates when the dependent measures were obtained. (B) All microdialysis sites were localized to the pontine reticular formation, which is comprised of the oral (PnO) and caudal (PnC) pontine reticular nuclei. Cylinders represent the dialysis membranes and are drawn to scale. (C) Drawing schematizes placement of a microdialysis probe in the PnO. The dialysis membrane at the ventral tip of the probe is drawn to scale. (D) A representative chromatogram shows a peak representing ACh obtained from the PnO during dialysis with Ringer’s (control).

Figure 6.

Acetylcholine (ACh) release in the pontine reticular formation (A and B), time for resumption of wakefulness after anesthesia (C and D), and breathing rate (E and F) varied as a function of drug concentration. Each drug concentration was tested in three mice. Asterisks identify concentrations of N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) and 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX) that caused a significant (P < 0.05) change from control (0 mM SPA or DPCPX).

Dialysis delivery of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX was used to determine whether endogenous adenosine acting at adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation modulates acetylcholine release, recovery time from general anesthesia, and rate of breathing. The 12 microdialysis sites from experiments with DPCPX were histologically confirmed to be in the pontine reticular formation (fig. 5B). Average stereotaxic coordinates for these dialysis sites were 4.9 ± 0.04 mm posterior to bregma, 4.8 ± 0.05 mm ventral to bregma, and 0.6 ± 0.06 mm lateral to the midline.20 Nonlinear regression analyses revealed that the concentration of DPCPX accounted for 77% of variance in acetylcholine release, 95% of variance in wake-up time, and 48% of the variance in breathing rate. One-way ANOVA showed there was no significant difference in total anesthesia time across experiments.

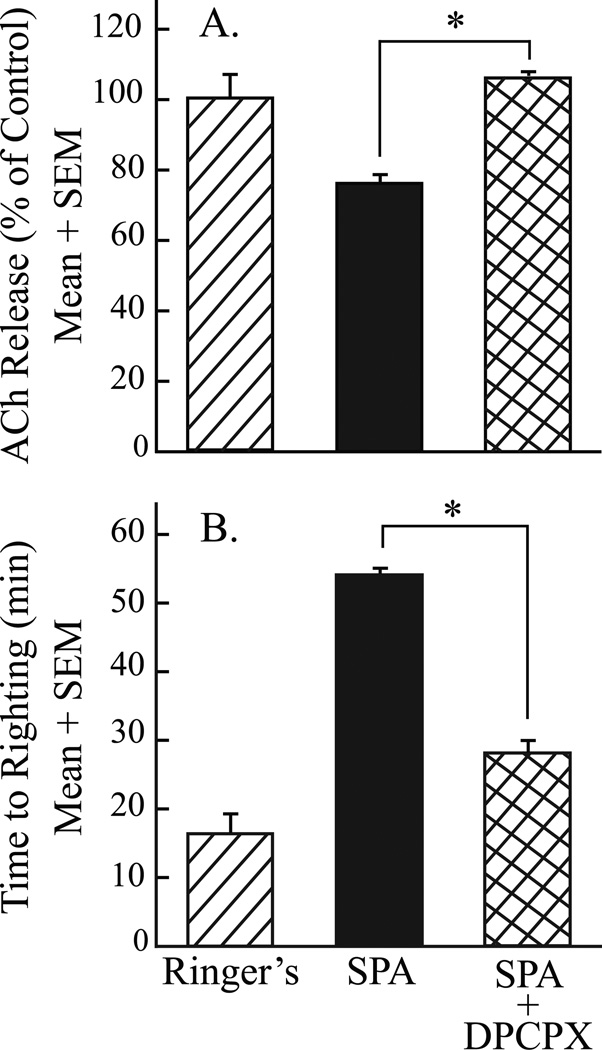

A final set of experiments (fig. 7) determined that the effects of SPA on acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation and behavioral arousal were blocked by coadministration of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX. The microdialysis sites from three experiments in which SPA and DPCPX were coadministered were histologically confirmed to be in the pontine reticular formation (fig. 5B) at 4.6 ± 0.14 mm posterior to bregma, 4.70± 0.05 mm ventral to bregma, and 0.8 ± 0.00 mm lateral to the midline.20 One-way ANOVA identified a significant drug main-effect on acetylcholine release (fig. 7A; F = 5.3; df = 2, 9; P = 0.03) and anesthesia recovery time (fig. 7B; F = 114.1; df = 2, 6; P < 0.0001). The Tukey/Kramer procedure demonstrated that coadministration of SPA and DPCPX to the pontine reticular formation blocked the SPA-induced decrease in acetylcholine release within the pontine reticular formation (fig. 7A, P < 0.05) and blocked the SPA-induced increase in wake up time from anesthesia (fig. 7B, P < 0.01). One-way ANOVA found no significant difference in total anesthesia time.

Figure 7.

Coadministration of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-sulfophenyl adenosine (SPA) and antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX) to the pontine reticular formation (A) blocked the SPA-induced decrease in acetylcholine (ACh) release, and (B) increased time to resumption of righting after isoflurane anesthesia. Data for SPA (solid bars) are from figure 6A and B (0.1 mM SPA). Asterisks indicate a significant (P < 0.05) difference from SPA.

Discussion

The results show for the first time that endogenous adenosine, acting at adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation, modulates breathing, behavioral arousal, and acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation. The potential clinical significance of these mechanistic data is discussed relative to evidence that cholinergic neurotransmission in the pontine reticular formation modulates breathing and promotes electroencephalographic activation that is characteristic of wakefulness.

Adenosine in the Pontine Reticular Formation Depressed Breathing by Actions at Adenosine A1 Receptors

Respiratory depression secondary to the loss of wakefulness is of key relevance for sleep-disorders medicine23 and anesthesiology.8 Although adenosine is known to modulate breathing24,25 and adenosine receptor antagonists are used to treat respiratory disorders such as asthma,26,27 the neuronal networks through which adenosine alters breathing are not understood. Adenosine A1 receptors are distributed widely in the human pontine reticular formation and in the cerebral cortex.28 The respiratory recordings of figure 2 illustrate that microinjection of SPA into the pontine reticular formation caused a prolonged depression of breathing. After microinjection of SPA, breathing was characterized by frequent episodes of apnea and by prolonged inspiration with occasional inspiratory gasps. Respiratory rate, tidal volume, and minute ventilation averaged over 2 h after microinjection of SPA into the pontine reticular formation were significantly depressed compared to measures of breathing after saline (control) injections (figs. 3A, C and E). The finding that the SPA-induced decrease in respiratory rate was concentration-dependent (fig. 6E) identifies receptor mediation as one underlying mechanism. The results are consistent with in vitro data showing that bath application of an adenosine A1 receptor agonist depresses respiratory-related phrenic discharge.29 The present results also extend the in vitro data from the spinal cord29 by identifying the pontine reticular formation as a supraspinal region where enhancing adenosinergic neurotransmission at adenosine A1 receptors suppresses breathing (figs. 3 and 6).

Although the pontine reticular formation contains no neurons that generate respiratory rhythm, the depression of breathing caused by microinjecting the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA into the pontine reticular formation (figs. 1–3) is consistent with documented connections between the pontine reticular formation and ponto-medullary respiratory nuclei.30 The fact that the pontine reticular formation does not contain neurons that generate the respiratory rhythm may, in part, account for the finding that DPCPX did not increase breathing, relative to saline control (fig. 6F). This is speculative but fits with the interpretation that the respiratory depression caused by SPA resulted from adenosinergic inhibition of wakefulness-promoting acetylcholine (fig. 6A). An additional limitation associated with the fig. 6 data is that inferences about breathing are based solely on measures of respiratory rate. The pontine reticular formation is a component of the reticular activating system and stimulation of this reticular core has long been known to activate both primary and secondary muscles of breathing.31 The gradual decline in the stimulating effect of wakefulness on respiratory rate also can be visualized in the time course data from mice that received saline injections (figs 3B, D, and F). By 120 min after the saline injection these mice displayed decreased grooming and locomotor activity, indicative of diminished arousal, and a decrease in all measures of breathing.

An Adenosine A1 Receptor Agonist Decreased Behavioral Arousal

Time to resumption of righting following isoflurane anesthesia was significantly prolonged by microinjection of SPA into the pontine reticular formation (fig. 4D). Dialysis delivery of SPA to the pontine reticular formation also caused a concentration-dependent increase in anesthesia recovery time (fig. 6C). The pontine reticular formation contributes to the regulation of sleep and wakefulness,9 anesthesia,32,33 and nociception.34–37 The present finding that delivery of SPA to the pontine reticular formation decreased behavioral arousal in B6 mice is consistent with data obtained from rat38 and cat39 showing that adenosine agonists in the pontine reticular formation depress wakefulness. The SPA-induced increase in time required for resumption of wakefulness (fig. 6C) and the DPCPX-induced reduction in wake-up time (fig. 6D) were both concentration-dependent, indicating mediation by adenosine A1 receptors. The DPCPX-induced promotion of arousal (fig. 6D) is consistent with data from asthma patients indicating that adenosine antagonists that cause a dose-dependent stimulation of breathing can also produce the unwanted side effect of sleep suppression.40

The finding that behavioral arousal was depressed by SPA should not be interpreted to imply effects that are restricted to the adenosine A1 receptor subtype. The increase in time to resumption of righting caused by SPA (figs. 4D and 6C) is in agreement with the discovery that delivery of the adenosine A2A receptor agonist 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenethylamino-5’-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS) into the pontine reticular formation of B6 mouse decreased wakefulness.41 The A2A receptor agonist CGS also decreased time to righting when delivered to the prefrontal cortex of B6 mouse.16 The prefrontal cortex42 and the pontine reticular formation contribute to the regulation of sleep and wakefulness, but adenosine A1 receptor-mediated alterations in behavioral arousal are not limited to these two brain regions. Throughout wide areas of the brain conditional deletion of the adenosine A1 receptor gene impairs the normal rebound increase in electroencephalographic slow wave activity that follows sleep restriction.43

Endogenous Adenosine in the Pontine Reticular Formation Modulates Behavioral Arousal and Breathing by Altering Acetylcholine Release

Systemic administration of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor physostigmine to humans reverses propofol anesthesia,44 and microinjection of neostigmine into the pontine reticular formation of B6 mice activates the electroencephalogram.19 Administration of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA into the pontine reticular formation by microdialysis caused a significant, concentration-dependent decrease in acetylcholine release within the pontine reticular formation (fig. 6A) and an increase in time required for resumption of waking after anesthesia (fig. 6C). The adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX delivered into the pontine reticular formation caused a concentration-dependent increase in acetylcholine release (fig. 6B) and a corresponding decrease in the time required for resumption of wakefulness (fig. 6D). Coadministration of SPA and DPCPX blocked the SPA-induced decrease in acetylcholine release (fig. 7A) and the SPA-induced increase in time to waking after anesthesia (fig. 7B). These findings are consistent with data from cat showing that dialysis delivery of SPA to pontine reticular formation caused a decrease in acetylcholine release and an increase in the time required to recover after anesthesia.39 Thus, the present results are generalizable across several species. Finally, the DPCPX data indicate that endogenous adenosine acting at adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation of B6 mouse decreases behavioral arousal and inhibits acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation.

In summary, the finding that the adenosine agonist SPA delayed emergence from anesthesia suggests that adenosine receptors in the pontine reticular formation suppress wakefulness. In addition, the concentration-dependence (fig. 6) and antagonist blocking (fig. 7) data support the conclusion that adenosinergic inhibition of wakefulness, breathing, and acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation is mediated by adenosine A1 receptors. Cholinergic neurons in the laterodorsal tegmental and pedunculopontine tegmental (LDT/PPT) nuclei promote arousal and stimulation of LDT/PPT nuclei increases acetylcholine release in the pontine reticular formation.45 Adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation are located presynaptically on cholinergic LDT/PPT neurons,11 and LDT neurons are inhibited by activating presynaptic or postsynaptic adenosine receptors.46 The present results support and extend the previous in vitro data by specifying the functional outcomes of activating adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation. The results also identify for the first time adenosinergic-cholinergic interaction in the pontine reticular formation as a component of normal respiratory drive contributing to the wakefulness stimulus for breathing.47

Final Boxed Summary Statement.

What we already know about this topic

Adenosine signaling in the central nervous system regulates sleep, pain, and breathing, but the networks, neurotransmitters, and receptors involved remain incompletely understood

What this article tells us that is new

In an in vivo mouse model, endogenous adenosine acting at adenosine A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation inhibits breathing, behavioral arousal, and acetylcholine release

Interactions between cholinergic and adenosinergic signaling in the pontine reticular formation regulate normal respiratory drive and contribute to the wakefulness stimulus for breathing

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sha Jiang, B.S. (Research Associate) and Mary A. Norat, B.S. (Senior Research Associate) from the Department of Anesthesiology, and Kathy Welch, M.A., M.P.H. (Statistician Staff Specialist, Center for Statistical Consultation and Research), University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan for expert assistance.

Support: Supported by grants HL65272 (RL), HL40881 (RL), and MH45361 (HAB) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and by the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Summary Statement: Adenosine acting at A1 receptors in the pontine reticular formation depresses breathing, increases anesthesia recovery time, and decreases acetylcholine release. These results suggest that an adenosinergic-cholinergic interaction contributes to the wakefulness stimulus for breathing.

References

- 1.Deer T, Krames ES, Hassenbusch SJ, Burton A, Caraway D, Dupen S, Eisenach J, Erdek M, Grigsby E, Kim P, Levy R, McDowell G, Mekhail N, Panchal S, Prager J, Rauck R, Saulino M, Sitzman T, Staats P, Stanton-Hicks M, Stearns L, Willis KD, Witt W, Follett K, Huntoon M, Liem L, Rathmell J, Wallace M, Buchser E, Cousins M, Ver Donck A. Polyanalgesic consensus conference 2007: Recommendations for the management of pain by intrathecal (intraspinal) drug delivery: Report of an interdisciplinary expert panel. Neuromodulation. 2007;10:300–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2007.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan TJ, Habib AS. Adenosine as a non-opioid analgesic in the perioperative setting. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:487–494. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000267260.00384.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredholm BB, Battig K, Holmen J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE. Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:83–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Muller CE. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors - An update. Pharm Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porkka-Heiskanen T, Kalinchuk AV. Adenosine, energy metabolism and sleep homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson AM, Battersby AS, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Opioid-induced decreases in rat brain adenosine levels are reversed by inhibiting adenosine deaminase. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1327–1333. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bdf894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauthier EA, Guzick SE, Brummett CM, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Buprenorphine disrupts sleep and decreases adenosine concentrations in sleep-regulating brain regions of Sprague Dawley rat. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:743–753. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822e9f85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mashour GA, Lydic R. Neuroscientific Foundations of Anesthesiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steriade M, McCarley RW. Brain Control of Wakefulness and Sleep. 2nd edition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. The neurochemistry of sleep and wakefulness. In: Brady ST, Albers RW, Price DL, Siegel GJ, editors. Basic Neurochemistry. New York: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 982–999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rainnie DG, Grunze HC, McCarley RW, Greene RW. Adenosine inhibition of mesopontine cholinergic neurons: Implications for EEG arousal. Science. 1994;263:689–692. doi: 10.1126/science.8303279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonard TO, Lydic R. Pontine nitric oxide modulates acetylcholine release, rapid eye movement sleep generation, and respiratory rate. J Neurosci. 1997;17:774–785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00774.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeMarco GJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Carbachol in the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mouse decreases acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2004;123:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex--an update: Time is of the essence. Neuron. 2001;30:319–333. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janiesch PC, Krüger H-S, Pöschel B, Hanganu-Opatz IL. Cholinergic control in developing prefrontal-hippocampal networks. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17955–17970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2644-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dort CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Adenosine A1 and A2A receptors in mouse prefrontal cortex modulate acetylcholine release and behavioral arousal. J Neurosci. 2009;29:871–881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4111-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flint RR, Chang T, Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. GABAA receptors in the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mouse modulate neurochemical, electrographic, and behavioral phenotypes of wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12301–12309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1119-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Icaza EE, Huang X, Fu Y, Neubig RR, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Isoflurane-induced changes in righting response and breathing are modulated by RGS proteins. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1500–1505. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ba7815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas CL, Bowman GN, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. C57BL/6J and B6.V-LepOB mice differ in the cholinergic modulation of sleep and breathing. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:918–929. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00900.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paxinos G, Franklin K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Second Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelz MB, Sun Y, Chen J, Cheng Meng Q, Moore JT, Veasey SC, Dixon S, Thornton M, Funato H, Yanagisawa M. An essential role for orexins in emergence from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1309–1314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707146105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonner JM, Gong D, Li J, Eger EI, 2nd, Laster MJ. Mouse strain modestly influences minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration and convulsivity of inhaled compounds. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1030–1034. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199910000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Edited by 5th. New York: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 1–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spyer KM, Thomas T. A role for adenosine in modulating cardio-respiratory responses: A mini-review. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:121–124. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herlenius E, Aden U, Tang LQ, Lagercrantz H. Perinatal respiratory control and its modulation by adenosine and caffeine in the rat. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:4–12. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RA, Spina D, Page CP. Adenosine receptors and asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S446–S456. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vass G, Horvath I. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the pathomechanism and treatment of respiratory diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:917–922. doi: 10.2174/092986708783955392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukumitsu N, Ishii K, Kimura Y, Oda K, Sasaki T, Mori Y, Ishiwata K. Adenosine A1 receptor mapping of the human brain by PET with 8-dicyclopropylmethyl-1-11C-methyl-3-propylxanthine. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong X-W, Feldman JL. Modulation of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons by presynaptic adenosine A1 receptors. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3458–3467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03458.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee LH, Friedman DB, Lydic R. Respiratory nuclei share synaptic connectivity with pontine reticular regions regulating REM sleep. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L251–L262. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orem J, Lydic R. Upper airway function during sleep and wakefulness: Experimental studies on normal and anesthetized cats. Sleep. 1978;1:49–68. doi: 10.1093/sleep/1.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Sleep, anesthesiology, and the neurobiology of arousal state control. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1268–1295. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown EN, Lydic R, Schiff ND. General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2638–2650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kshatri AM, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Cholinomimetics, but not morphine, increase antinociceptive behavior from pontine reticular regions regulating rapid-eye-movement sleep. Sleep. 1998;21:677–685. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanase D, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Microinjection of an adenosine A1 agonist into the medial pontine reticular formation increases tail flick latency to thermal stimulation. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1597–1601. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200212000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Leptin replacement restores supraspinal cholinergic antinociception in leptin-deficient obese mice. J Pain. 2009;10:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson SL, Watson CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Thermal nociception is decreased by hypocretin-1 and an adenosine A1 receptor agonist microinjected into the pontine reticular formation of Sprague Dawley rat. J Pain. 2010;11:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marks GA, Shaffery JP, Speciale SG, Birabil CG. Enhancement of rapid eye movement sleep in the rat by actions at A1 and A2a adenosine receptor subtypes with a differential sensitivity to atropine. Neuroscience. 2003;116:913–920. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanase D, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Dialysis delivery of an adenosine A1 receptor agonist to the pontine reticular formation decreases acetylcholine release and increases anesthesia recovery time. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:912–920. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200304000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mastronarde JG, Wise RA, Shade DM, Olopade CO, Scharf SM. Sleep quality in asthma: Results of a large prospective clinical trial. J Asthma. 2008;45:183–189. doi: 10.1080/02770900801890224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coleman CG, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Dialysis delivery of an adenosine A2A agonist into the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mouse increases pontine acetylcholine release and sleep. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1750–1759. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muzur A, Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. The prefrontal cortex in sleep. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:475–481. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bjorness TE, Kelly CL, Gao T, Poffenberger V, Greene RW. Control and function of the homeostatic sleep response by adenosine A1 receptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1267–1276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2942-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meuret P, Backman SB, Bonhomme V, Plourde G, Fiset P. Physostigmine reverses propofol-induced unconsciousness and attenuation of the auditory steady state response and bispectral index in human volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:708–717. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Pedunculopontine stimulation alters respiration and increases ACh release in the pontine reticular formation. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R544–R554. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.3.R544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arrigoni E, Rainnie DG, McCarley RW, Greene RW. Adenosine-mediated presynaptic modulation of glutamatergic transmission in the laterodorsal tegmentum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1076–1085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01076.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fink BR. Influence of cerebral activity in wakefulness on regulation of breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:15–20. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]