Abstract

Epithelial ovarian cancer, once categorizing all epithelial cancers of the ovary and fallopian tube, is now recognized to be an umbrella term. We are recognizing two categories of ovarian cancer, with the “type 1” cancers containing further types, including low grade serous cancers, mucinous, clear cell, and low grade endometrioid. These types are genetically and histologically as different as is their outcome. The paper accompanying this editorial further dissects low grade serous cancers to show that those carrying oncogenic KRAS or BRAF mutations have an unexpectedly excellent clinical outcome. We discuss this newest unexpected behavior of ovarian cancer.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, KRAS, BRAF, serous, borderline tumor

Once again we find epithelial ovarian cancer forging its own path rather than following the classical paths forged by other carcinomas. These classical paths describe carcinomas as having a select cell of origin, spreading by nodal extension and hematogenous dissemination, generally metastasizing to first encountered capillary beds, and more recently, having mutational activation of a signaling pathway that creates a dominant driving event. This dominant driving event portends poor outcome and, when interrupted therapeutically, results in clinical benefit. We are learning that what we have known as epithelial ovarian cancer is really a collection of cancers of Mullerian origin 1. These Mullerian cancers shed into and spread within the peritoneal cavity long before lymphovascular dissemination, and their genetic and genomic events are varied.

The recent and significant growth in our understanding of epithelial ovarian cancers, has led us to recognize its increasingly divergent behavior. The two type system proposed by Shih and Kurman in 2004 1 is now generally accepted. Type 2 cancers encompass the high grade serous cancers, both more common and also accounting for the frequent late stage diagnosis and worse outcome 2–4. Type 2 tumors contain mutant p53 and frequently have abnormalities in homologous recombination DNA repair pathways, including BRCA1/2 mutations, resulting in genomic instability and varied genomic signatures, rather than subsets with definable drivers 5–7. They grow rapidly with a high mitotic index and are responsive to platinum-based chemotherapy. Provocative data suggest that these cancers arise from the distal fallopian tube 8,9. There are equally strong arguments that type 1 ovarian cancers, currently encompassing the low grade serous, clear cell, low grade endometrioid, and transitional cell histologies, need to be broken out into types, rather than subtypes. These different types can be readily separated by a combination of histology and genomics (Fig 1) 10,11. Thus, this “reinvention” of the component parts of epithelial ovarian cancers leaves great opportunities to better understand what each means to the patient.

Figure 1. Epithelial ovarian cancers are now divided into two categories.

Type 1 cancers are now recognized to have 4 types, low grade serous, low grade endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous histologies. Type 2 cancers include in one unit, both the high grade serous and now most agree, also the high grade endometrioid histologies.

The paper presented by Grisham and colleagues in this edition of Cancer furthers our understanding of the molecular basis and behavior of type 1 low grade serous ovarian tumors. Markedly different from type 2 high grade serous cancers, there are strong arguments that low grade serous cancers arise in or from serous borderline tumors of the ovary 12–14. They are slowly growing tumors with a low mitotic index and are now believed to be poorly responsive to platinum-based chemotherapy, yet are associated with 10 year survivals superior to the type 2 high grade serous cancers. These low grade serous borderline tumors and cancers are genetically stable and, as a class, have wild type p53 and BRCA1/2 genes.

This type 1 ovarian cancer subtype is characterized by mutations in a number of genes, most commonly KRAS and BRAF 1,15,16. Grisham and colleagues report that 57% of tumors harbored a BRAF (n=26) or KRAS (n=17) mutation within the 75 patients whose tumors were analyzed. All BRAF mutations (35%) were V600E, and all KRAS mutations were codon 12, either G12D (n=11) or G12V (n=6). BRAF and KRAS mutations were mutually exclusive. The sites of mutation, V600E in BRAF and codon 12 in KRAS, are long recognized to be oncogenic 17,18. What do we know of solid tumors bearing KRAS and BRAF mutations? In colon cancer, melanoma, and thyroid cancers, KRAS and BRAF mutation-bearing tumors are more aggressive than their wild-type counterparts 19–22. Only the recent application of BRAF-targeted therapeutics has changed the survival landscape of the BRAF-mutated melanoma 21,23. Vemurafenib, a selective BRAF-targeted agent, was recently FDA-approved for V600E BRAF mutant melanoma. Paradoxically, though rare at 5% of cases, colon cancers with a V600E BRAF mutation responded poorly to therapy 24 and it is well recognized that presence of KRAS mutation is associated with poor response to EGFR inhibitors 25,26. This lack of response occurred due to the upregulation of EGFR causing activation of the downstream survival protein, AKT. This also explains why attempts to treat BRAF V600E or KRAS mutant bearing colon tumors with an EGFR inhibitor were unsuccessful.

If ovarian cancer was to follow the trend of other solid tumors, then those tumors with a BRAF or KRAS mutation should behave poorly. Yet, this is not the case as low grade serous cancers and serous borderline tumors, have long been recognized to have a better prognosis. Grisham’s paper shows us that, also contrary to the genetic progression usually seen in solid tumors, there is loss rather than gain of the BRAF or KRAS mutation. Grisham and coworkers demonstrate the highest frequency of mutation is in the borderline tumors, with mutational loss with progression to micropapillary tumor and low grade serous carcinoma. Lastly, they show that those low grade serous cancers that have the BRAF mutation did not recur with no deaths at a median follow up of 43 months. This is the antithesis of what we expect with these oncogenic mutations.

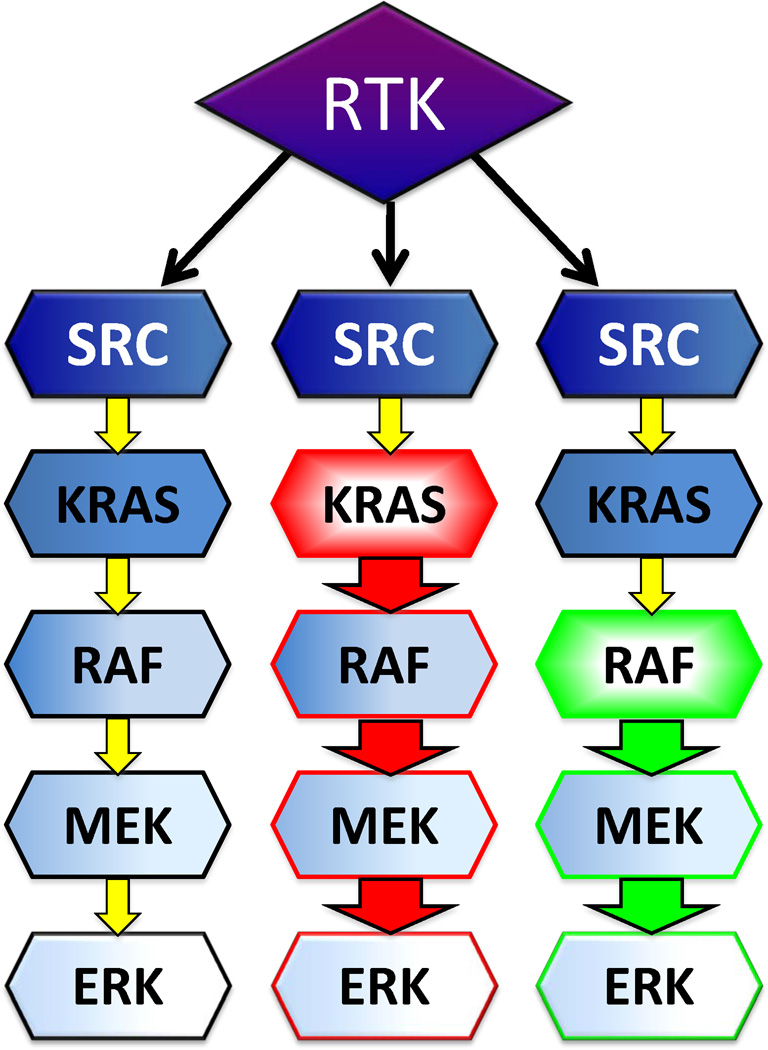

How do we capitalize on these new findings? The earlier recognition of the presence of BRAF and KRAS mutations in low grade serous cancers led to the logical choice of targeted therapy, using a MEK inhibitor, selumetinib (AZD6244; GOG-239; Farley et al, presented at the 2012 Society for Gynecologic Oncology meeting, Austin TX). MEK is immediately downstream of BRAF (fig 2) in the RAS→ RAF pathway and would be expected to be activated downstream of the mutation and thus a logical site to target. GOG-239 (NCT00551070) was a single arm two-step phase 2 trial of selumetinib 50mg twice daily continuously, specifically for low grade serous ovarian cancer patients; results were reported at the 2012 Society for Gynecologic Oncology meeting. A total of 52 women were entered, of those for whom mutational analysis was completed at the time of the report, 41% had KRAS mutations and 6% had BRAF mutations. There was an overall 16% response rate and median progression-free survival of approximately 7 months. The BRAF mutation carriers were less likely to be the responders, suggesting MEK pathway may be important in low grade serous cancers with other driving pathways. As pointed out by Grisham and colleagues, this could also be interpreted that those patients BRAF mutations did not recur and therefore are under-represented in this multi-institutional cohort.

Figure 2. RAF→RAS signaling.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) signal through Srchomology-2 domains to Src. It in turn activates the pathway to KRAS, RAF, to ultimately activate the mitogen-activated kinase, MAPK, pathway via MEK to ERK. An activating mutation in KRAS (shown in red), such as the codon 12 and 13 mutations described in low grade serous ovarian cancer, can drive downstream activation of the MAPK pathway without upstream the otherwise needed upstream stimulation by RTK. Similarly, an activating mutation in BRAF (shown in green), such as V600E

Grisham and colleagues have added important new findings of our understanding of the molecular basis and clinical behavior of type I ovarian cancers. These findings are important in that they can lead to triage decisions to reduce overtreatment of those women whose cancers are unlikely to recur. Continued evaluation of the molecular and proteomic pathway events underlying ovarian cancers will lead to improvements in our clinical trial directions and designs, and ultimately to improved quality and quantity of life for our patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute (EK).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ. Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1511–1518. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63708-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matulonis UA, Hirsch M, Palescandolo E, et al. High throughput interrogation of somatic mutations in high grade serous cancer of the ovary. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merritt MA, Cramer DW. Molecular pathogenesis of endometrial and ovarian cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2010;9:287–305. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2011-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vang R, Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ. Ovarian low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma: pathogenesis, clinicopathologic and molecular biologic features, and diagnostic problems. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:267–282. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181b4fffa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang J, D'Andrea AD, Kozono D. A DNA repair pathway-focused score for prediction of outcomes in ovarian cancer treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:670–681. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mankoo PK, Shen R, Schultz N, et al. Time to recurrence and survival in serous ovarian tumors predicted from integrated genomic profiles. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:230–236. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000180854.28831.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2007;211:26–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Baker PM, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma cell type is highly reproducible: a transcanadian study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:984–993. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e1a3bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Santos JL, et al. Tumor type and substage predict survival in stage I and II ovarian carcinoma: insights and implications. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell SE, McCluggage WG. A multistep model for ovarian tumorigenesis: the value of mutation analysis in the KRAS and BRAF genes. J Pathol. 2004;203:617–619. doi: 10.1002/path.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer G, Oldt R, 3rd, Cohen Y, et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:484–486. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer G, Stohr R, Cope L, et al. Patterns of p53 mutations separate ovarian serous borderline tumors and low- and high-grade carcinomas and provide support for a new model of ovarian carcinogenesis: a mutational analysis with immunohistochemical correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:218–224. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146025.91953.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurman RJ, Visvanathan K, Roden R, et al. Early detection and treatment of ovarian cancer: shifting from early stage to minimal volume of disease based on a new model of carcinogenesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell DA. Origins and molecular pathology of ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(Suppl 2):S19–S32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Mancera PA, Tuveson DA. Physiological analysis of oncogenic K-ras. Methods Enzymol. 2006;407:676–690. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sartore-Bianchi A, Bencardino K, Cassingena A, et al. Therapeutic implications of resistance to molecular therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(Suppl 3):S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)70012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lievre A, Blons H, Laurent-Puig P. Oncogenic mutations as predictive factors in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:3033–3043. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantwell-Dorris ER, O'Leary JJ, Sheils OM. BRAFV600E: implications for carcinogenesis and molecular therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:385–394. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5705–5712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1308–1324. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lievre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3992–3995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]