Alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), a mechanism involving the replication of new telomeric DNA from a DNA template, is used by some cancer cells to lengthen their telomeres. Reddel and colleagues now show that ALT activity exists in normal somatic tissues as well. A telomere with a DNA tag is found to be intertelomerically copied in normal somatic cells but not germline cells, providing important implications for understanding telomere maintenance and its evolution.

Keywords: ALT, recombination, telomeres

Abstract

Some cancers use alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), a mechanism whereby new telomeric DNA is synthesized from a DNA template. To determine whether normal mammalian tissues have ALT activity, we generated a mouse strain containing a DNA tag in a single telomere. We found that the tagged telomere was copied by other telomeres in somatic tissues but not the germline. The tagged telomere was also copied by other telomeres when introgressed into CAST/EiJ mice, which have telomeres more similar in length to those of humans. We conclude that ALT activity occurs in normal mouse somatic tissues.

Vertebrate telomeres contain many tandem repeats of the sequence 5′-TTAGGG-3′ (Meyne et al. 1989). In normal somatic cells, telomeres shorten with every cell division, whereas in germline cells and many immortalized cell lines and cancers, telomere length is maintained by the enzyme telomerase (Shay and Bacchetti 1997), which synthesizes new telomeric DNA by reverse-transcribing the template region of its RNA subunit (Greider and Blackburn 1989). Some immortalized cell lines and cancers lengthen their telomeres without telomerase (Bryan et al. 1995, 1997) by synthesizing new telomeric DNA using telomeric DNA as the copy template (for review, see Cesare and Reddel 2010). To test the hypothesis that this alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) activity occurs in normal mammalian cells, we generated a telomere-tagged transgenic mouse strain and examined whether other telomeres copy the tagged telomere.

Results and Discussion

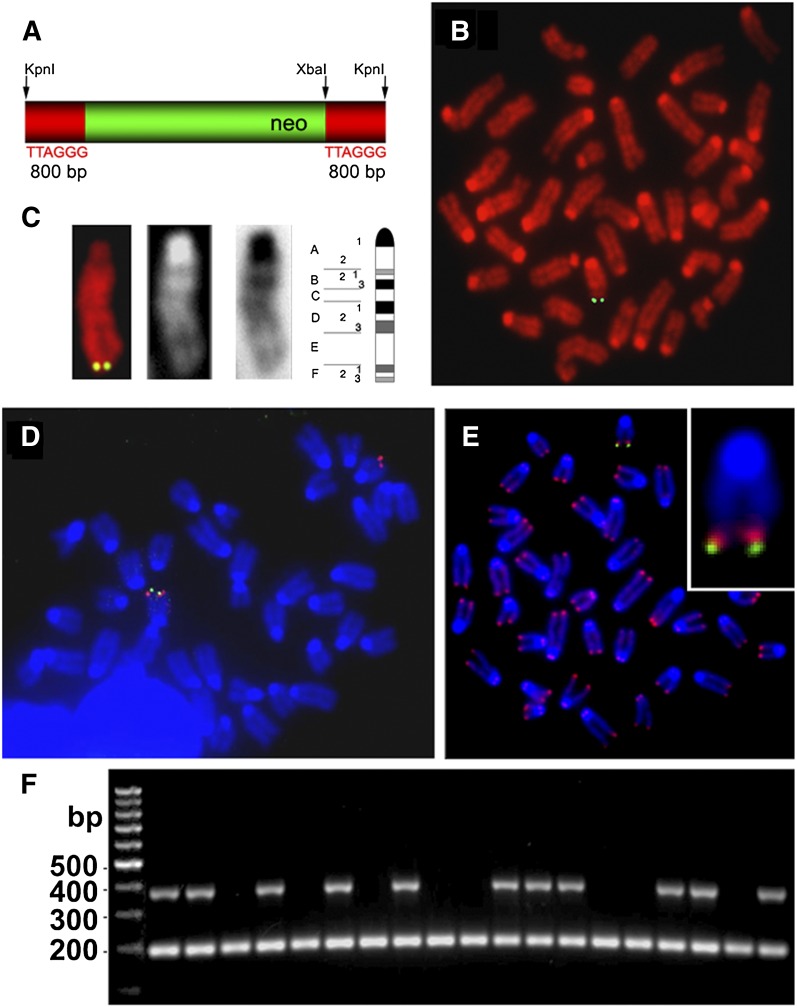

R1-129 mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were electroporated with a telomere targeting construct, Tel (Fig. 1A; Dunham et al. 2000). Of 13 G418-selected R1-129 ESC clones, one (designated R1-10) contained a single telomeric integration site of Tel in the chromosome 15 long arm as detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Fig. 1B–D). The intratelomeric location was verified by dual-color FISH, which detected a telomeric sequence proximal to Tel (Fig. 1E). We did not observe the tag at any site other than chromosome 15q in R1-10 ESCs after 13 passages in vitro, suggesting that telomere–telomere copying may not be active in mouse ESCs under these conditions, although it has been reported that telomere lengthening can occur during transient Zscan4 activation (Zalzman et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

Inheritance of the telomere-targeted DNA tag Tel. (A) Schematic representation of the telomere targeting construct Tel, consisting of a neomycin resistance cassette (neo; green) that, after KpnI digestion, is flanked by 800-bp telomeric repeats (red) on either side. (B) Integration of the Tel tag (green) into a single chromosome, detected by FISH using a biotinylated plasmid pSXneo probe on a colcemid-arrested metaphase chromosome spread of R1-10 ESCs (passage 3) after G418 selection. (C) The tagged chromosome arm (green signal on red chromosome; left panel) was identified as 15q by the direct (white chromosome; second panel from left) and inverse DAPI (black chromosome; second panel from right) banding pattern. (Right) The location of the tag was chromosome band 15F3 (with reference to the mouse idiogram). (D) Identification of the tagged chromosome end was confirmed in a colcemid-arrested metaphase spread by cohybridization of biotinylated plasmid pSXneo (green) and a digoxigenin-labeled BAC probe, 15-T (red), specific for mouse chromosome 15q subtelomere. (E) Telomeric integration of the Tel tag (green) was demonstrated by FISH on metaphase chromosomes hybridized sequentially with pSXneo plasmid probe and detected with avidin-FITC (green) and a telomere-specific Cy3-conjugated PNA probe (red). Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The proximal telomere FISH signal relative to the pSXneo signal (see the magnified insert) indicates that the Tel construct is integrated intratelomerically. (F) PCR genotyping indicated Mendelian inheritance of the Tel tag in 50% of the established C29 mouse strain. The top band shows the neoR-PCR product of 380 bp and the internal control intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (FABPI) product of 194 bp in size. As shown in the representative gel, ∼50% (11 out of 19 samples) of the mice in a hemizygous mating were transgenic for the Tel tag.

Chimeric mice were generated by blastocyst injections of R1-10 ESCs. One (B11) of three Balb/c and one (C29) of 20 C57BL/6 blastocyst injection chimeras were germline transmitters of Tel as determined by neoR-PCR genotyping. Mice generated from founders B11 and C29 were bred for six generations onto an R1-129 background and for 13 generations onto a C57BL/6 background, respectively, with the transgene being transmitted by both male and female parents; no phenotypic abnormality was detected. Telomere copying in the germline would result in >50% of offspring being transgenic, but inheritance was Mendelian in both lines (Fig. 1F). After this was observed in the B11 line over six generations, all further studies were of the C29 line, where exactly 50% (357 of 714 pups) were transgenic over 13 generations. There was therefore no evidence of ALT activity in the germline, including during meiosis.

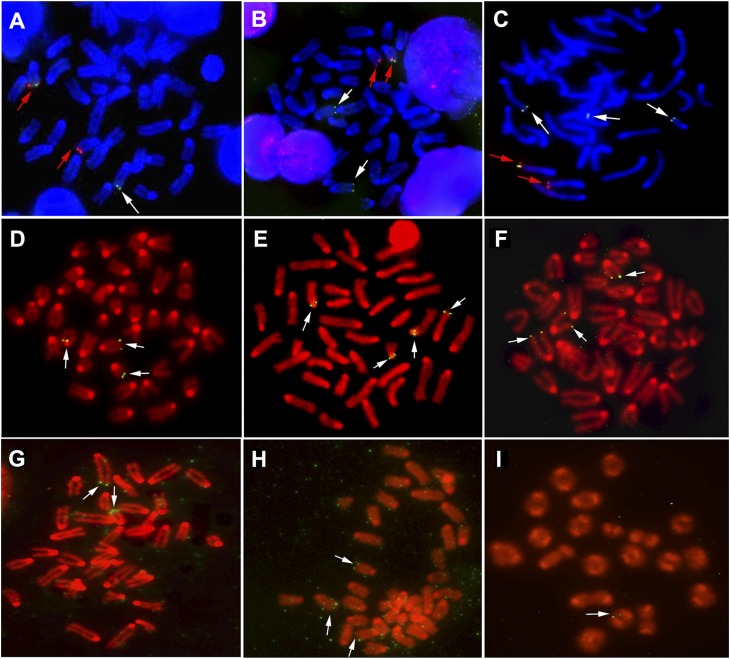

FISH analysis of colcemid-arrested metaphases, all of which were euploid, from isolated splenocytes that had been stimulated ex vivo for 48 h with a combination of B- and T-cell mitogens (lipopolysaccharide [LPS] and Concanavalin A [Con A]) showed that the telomere tag was copied from chromosome 15 onto other chromosomes (Fig. 2A–D). In metaphases where the tag was identified unequivocally in its original chromosome 15 location, 49% also had a copy of the tag at one or more additional chromosome ends. The additional locations appeared to be random, indicating that no chromosome (including the chromosome 15 homolog) was preferentially involved in telomere copying. We isolated naive B- and T-cell populations of 90%–95% purity, as determined by FACS analysis (data not shown), from splenocyte suspensions and stimulated them for 48–72 h ex vivo with cell type-specific mitogens—LPS or Con A, respectively. FISH analysis again showed that Tel was present on both chromosome 15 and other telomeres in both B and T cells (Fig. 2E,F, respectively), and this was also detected in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Fig. 2G) and dermal keratinocytes (Fig. 2H) but not in spermatocytes (Fig. 2I). A very small percentage of MEFs was tetraploid, and these were excluded from further analysis. Of 420 euploid MEF metaphases where a tagged chromosome 15 was unequivocally identified, 130 (31%) also had a copy of the tag on one or more additional chromosome ends.

Figure 2.

Copying of the Tel tag from chromosome 15 onto other telomeres in mouse tissues. (A–C) Splenocytes were grown for 48 h ex vivo followed by chromosome harvest and cohybridization of biotinylated plasmid pSXneo (green) and a digoxigenin-labeled BAC probe, 15-T (red), specific for mouse chromosome 15q subtelomere. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The two homologous chromosomes 15 are indicated with red arrows (one of which is the originally tagged chromosome with a green hybridization signal), and additional neo-tagged chromosome ends are indicated by white arrows. (D) Splenocytes were grown for 48 h ex vivo, followed by chromosome harvest and FISH with biotinylated pSXneo plasmid as a probe and detection with avidin-FITC. Chromosome spreads were counterstained with DAPI and pseudo-colored red. Examples of metaphases are shown, where chromosome ends in addition to the tagged chromosome 15 show a hybridization signal (white arrows), demonstrating that the Tel tag has been copied. The following cell types were analyzed in the same way. (E,F) B cells and T cells were isolated and cultured ex vivo for 48 h in the presence of LPS and for 72 h in the presence of Con A, respectively. (G) MEFs isolated from individual embryos were grown ex vivo for up to 5 d. (H) Adult mouse skin keratinocytes were grown from tail skin for 5 d. (I) Direct preparations of spermatocytes were made from testes of mice that were at least 8 wk old; no copying of the Tel tag was observed.

Although these observations clearly indicate that telomeres in normal mouse somatic cells are lengthened by copying DNA present in other telomeres, the proportion of cells containing multiple tags (49% and 31% of splenocytes and MEFs, respectively) is not equivalent to the frequency of lengthening events for several reasons. First, detection of an additional tag does not indicate whether the copying event occurred in that cell or in one of its predecessors. Second, the assay detects only the subset of de novo telomere extension events where the copy template happens to be the tagged telomere. Third, the assay was not designed to detect telomere extension events involving other telomeric copy templates, such as another region of the same telomere (Muntoni et al. 2009).

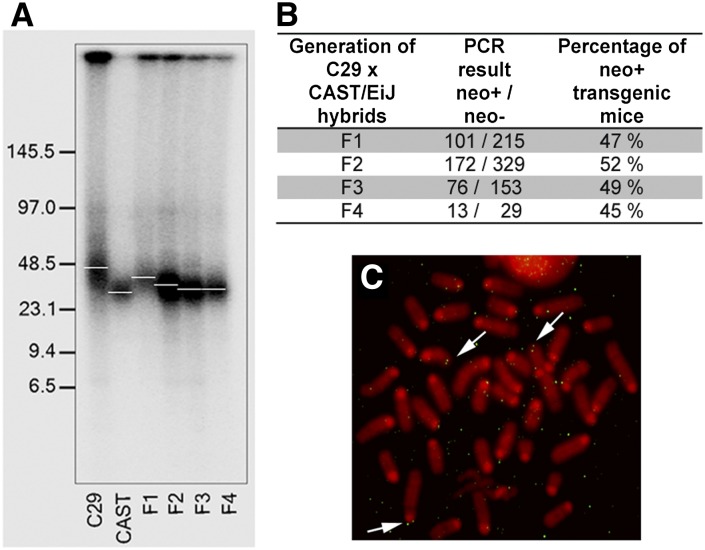

To test whether telomeric copy templating is unique to the Mus musculus strain with long telomeres, we introgressed Tel to mice with shorter telomeres. (C29 × CAST/EiJ)F1 mice were backcrossed to M. musculus castaneus (CAST/EiJ) mice for four generations, until the telomere lengths were similar to nonhybrid CAST/EiJ (Fig. 3A). Transgene inheritance followed the Mendelian pattern, and copying of the 15q tag to telomeres of other chromosomes was detected in lymphocytes (Fig. 3B,C).

Figure 3.

Copying of the Tel tag from chromosome 15 onto other telomeres in CAST/EiJ mouse tissues. (A) Southern analysis of terminal restriction fragments (TRFs) of DNA from Tel-tagged C29 mice, CAST/EiJ mice, and Tel-tagged C29 × CAST/EiJ hybrids, generations F1, F2, F3, and F4. Wild-derived CAST/EiJ mice have shorter telomeres than C29 mice (C57BL/6). Generation F1 hybrids have a bimodal telomere length distribution, where long C57BL/6 telomeres became shorter, and the short CAST/EiJ telomeres became longer. With continuous breeding of the Tel-tagged mice against a CAST/EiJ background, the median telomere length (white lines) of the hybrids had attained that of the parental CAST/EiJ strain by generation F4. (B) Genotyping showed that, as observed in the C57BL/6 background (C29 mice), the Tel tag segregated in a Mendelian manner, with ∼50% of the C29 × CAST/EiJ hybrid offspring being transgenic, indicating that telomere copying did not occur in the germline. (C) FISH analyses of chromosome spreads from generation F4 C29 × CAST/EiJ splenocytes. Splenocytes from F4 hybrids were grown and analyzed as described in Figure 2A. In addition to chromosome 15, telomeres from other chromosomes have a hybridization signal (arrows), demonstrating that copying of the Tel tag onto other chromosomes has occurred also in mice with telomere lengths more similar to those in humans.

The presence of ALT activity had previously been deduced from the observation that certain telomerase-negative immortalized mammalian cells are able to maintain the length of their telomeres (Bryan et al. 1995, 1997; Hande et al. 1999; Niida et al. 2000; Zou et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2003). In other situations—e.g., in fixed tumor samples where it is not possible to test whether telomere length is maintained during cellular proliferation or where cells or tissues have telomerase activity—ALT activity has been detected indirectly based on the presence of telomere phenotypes that are characteristic of cell lines that use ALT, such as ALT-associated PML bodies or abnormally large fluctuations in telomere length (Murnane et al. 1994; Bryan et al. 1997; Hande et al. 1999; Henson et al. 2005; Perrem et al. 2001; Morrish and Greider 2009). The ALT reporter mouse strain that we described here, however, is designed to detect synthesis of new telomeric DNA using another telomere as the copy template. This permits detection of ALT in the presence of telomerase and does not depend on detecting the absence of telomere shortening or the presence of the hallmarks of ALT-positive immortalized cells, many of which might only be present when ALT activity is dysregulated.

We did not detect ALT activity in the mouse germline. The number of germ cell divisions per mouse generation has been observed to be 25 in females and 34–133 in males (Drost and Lee 1995) or ∼50 cell divisions per generation, based on the observations that telomerase-null mice lose ∼5 kb of telomeric DNA per mouse generation and ∼100 base pairs (bp) per cell division (for review, see Lansdorp 2009). Therefore, in the Tel-tagged C29 mouse, we observed no Tel copying in ∼650 germ cell divisions (13 generations). Consistent with this, FISH analysis of spermatocytes found no evidence for tag copying by other telomeres. Tel tag copying very early in development would result in a substantial proportion of somatic cells having the same telomere tagged in addition to 15q, but this was not observed. A study concluding that there is ALT activity in early cleavage embryos (Liu et al. 2007) may be compatible with our data, however, given that our assay detects only copying of another telomere and not intratelomeric templating, which also occurs in ALT (Muntoni et al. 2009).

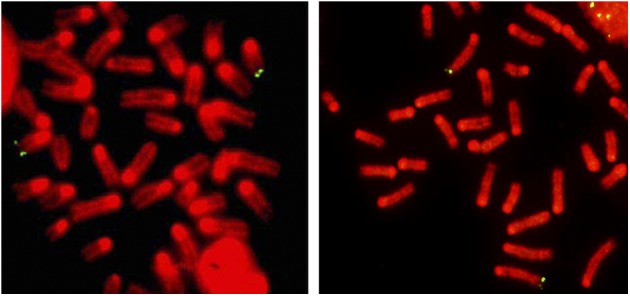

Another study reported frequent subtelomeric recombination events in cells from late-generation telomerase-null mouse Eμmyc+ tumors with short telomeres but not in primary telomerase-positive bone marrow cells (Morrish and Greider 2009). We hybridized chromosome spreads from activated splenocytes with subtelomeric bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) probes for chromosome 2 (Morrish and Greider 2009) and chromosome 15 (Korenberg et al. 1999). No recombination events involving other chromosomes were detected by either probe in any metaphase (n = 50) (Fig. 4), in agreement with previous studies (Dunham et al. 2000; Rudd et al. 2007).

Figure 4.

FISH analysis with chromosome-specific subtelomeric probes of stimulated splenocytes. FISH with BAC probes specific for the subtelomeric region of the long arm of chromosome 15 (green avidin-FITC signals; left panel) or for the long arm of chromosome 2 (green avidin-FITC signals; right panel) consistently only demarcated either chromosome 15 or chromosome 2 homologs, respectively. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI and pseudo-colored red.

We presented evidence that in several somatic tissues, telomeric DNA was synthesized using the tagged telomere as the copy template. We cannot rule out the possibility that the telomeric tag perturbs normal telomere function. However, our detection of ALT activity in splenocytes is supported by evidence that splenocytes of late-generation telomerase-null mice underwent telomere lengthening after immunization (Herrera et al. 2000). Although the possibility that immunization resulted in selection of a pre-existing population of splenocytes with long telomeres was not ruled out, the data were consistent with telomere lengthening by ALT. A potential caveat is that the ALT activity might be an in vitro artifact because our detection method required ex vivo culture to obtain metaphase chromosomes, but in many cases, this took only a few days. A further caveat we considered is that the result might be relevant only to species with very long telomeres, but when we introgressed the Tel tag to CAST/EiJ mice that have shorter telomeres, we found that telomere–telomere copying events occurred in these animals also.

Our results indicate that ALT activity may be a normal component of telomere biology in mammalian somatic cells in vivo. ALT therefore appears to be analogous to telomerase in that both of these mechanisms for synthesizing new telomeric DNA may be present in normal somatic tissues but at levels insufficient to prevent gradual telomere shortening, and either may become up-regulated in immortalized cell lines and cancers to levels that result in telomere length maintenance.

It has been proposed that recombination-mediated telomere synthesis was the archetypal telomere lengthening mechanism when eukaryotes first evolved linear chromosomes and that this was permanently repressed when it was superseded by telomerase in later eukaryotes (de Lange 2004). Our data support the speculation that well-regulated ALT activity has persisted in eukaryotic cells until now. We found that ALT is more tightly repressed in the germline for unknown reasons, and in agreement with this observation, it is clear that ALT does not substitute for telomerase in the germline of telomerase-null mice because they undergo intergenerational telomere shortening (Blasco et al. 1997). The paucity of prior direct evidence for ALT activity in normal cells may be due to the difficulty of detecting a nontelomerase mechanism when telomerase is also active. Dysregulation of this normal ALT activity presumably results in the abnormal telomere phenotype seen in ALT-positive cancer cells. Given that ALT is an attractive therapeutic target in ALT-positive cancers, it will be important to understand the role of ALT in normal mammalian tissues to predict the side effects of ALT inhibitors.

Materials and methods

Mice

All animal studies were performed in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes and were authorized by the Children’s Medical Research Institute/Children’s Hospital at Westmead Animal Ethics Committee.

ESC culture and electroporation

R1-129 mouse ESCs were cultured according to established procedures in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), nonessential amino acids, leukemia inhibitory factor, and β-mercaptoethanol (Nagy 2003). The Tel telomere targeting construct (Fig. 1A; Dunham et al. 2000) was linearized with KpnI, and the corresponding fragment was gel-purified. After G418 selection, colonies were expanded and screened for telomeric integration by FISH.

Splenocyte isolation and culture

Spleens were removed from euthanized mice and stored in ice-cold sterile PBS before they were transferred into 70-μm cell strainers (BD Falcon) in a 100-mm dish with PBS-CMF and forced through the mesh. Red blood cells were lysed in 10 mM KHCO3, 150 mM NH4Cl, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 5% FBS. Cells were washed with 10% FBS-supplemented RPMI 1640 medium and either set up as splenocyte cultures or processed for isolation of B and T cells.

Enrichment of B and T cells

B and T cells were purified using a B-cell isolation kit and a pan-T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified B cells were mitogenically stimulated with 15 μg/mL LPS (from Salmonella typhosa; Sigma) and cultured for 48–72 h. Pan-T cells were mitogenically stimulated with 5 μg/mL Con A (Sigma) and cultured for 72 h.

Flow cytometry analysis of purified splenocytes

The purity of B and T cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. Cell fractions were stained with a fluorochrome-conjugated antibody against B-cell or pan-T-cell markers; i.e., CD45R (B220) for B cells and CD90 for pan-T cells (both from Miltenyi Biotec). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a FACSCanto flow cytometer with a 488-nm argon ion laser and a 633-nm diode laser.

Keratinocyte isolation and culture

Skin keratinocytes were isolated from tails of euthanized adult mice. Skins were incubated overnight in dispase (Sigma) made up in keratinocyte medium-SFM (GIBCO) at a final concentration of 5 mg/mL. The epidermis was transferred into a new dish with TryPLE Select enzyme (GIBCO) with the basal layer downward and was incubated at room temperature. Keratinocytes were seeded in collagen-coated T75 culture flasks (Falcon) at a density of 4 × 104 to 5 × 104 cells per square centimeter and grown without feeder layers in keratinocyte medium-SFM (GIBCO) with 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor and 10−10 M cholera toxin (Yano and Okochi 2005).

Spermatocyte isolation

Male mice older than 8 wk were euthanized, and testes were excised and transferred to a tube containing 2% trisodium citrate. Testes were detunicated, seminiferous tubules were finely chopped, and spermatocytes were released by repeated pipetting and filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer. Cells were resuspended in 1% trisodium citrate for 30 min, followed by fixation with methanol:glacial acetic acid (3:1).

Isolation of metaphase chromosomes

Metaphase chromosomes were harvested by adding Colcemid (KaryoMax, GIBCO) at a concentration of 0.1 μg/mL for 2 h for ESCs and splenocytes or for 4 h for fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Cells were resuspended in hypotonic 0.8% trisodium citrate, followed by fixation with a 3:1 mixture of methanol and glacial acetic acid.

Slide pretreatment for FISH

Slides were incubated in RNase A (Sigma) solution at 100 μg/mL in 2× SSC for 1 h at 37°C, followed by three 5-min washes in 2× SSC. Slides were prefixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS, followed by digestion in 0.1% pepsin (Sigma) solution in 10 mM HCl (pH 2.0) for 10 min at 37°C. After three washes with PBS, slides were dehydrated through an ascending ethanol series and air-dried.

DNA probes for FISH

Plasmid pSXneo and the subtelomeric BAC clones for mouse chromosome 2 (RPCI-23 391E5, Invitrogen) and mouse chromosome 15 (CT7 62I2, Invitrogen) were purified using the HiPure plasmid filter purification kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cy3-conjugated mouse chromosome 15 painting probe (StarFish, Cambio) was purchased ready to use. Double-stranded plasmid and BAC DNA probes were labeled by nick translation with biotin-16-dUTP or digoxigenin-11-dUTP using a Biotin-Nick Translation mix and a DIG-Nick Translation mix (Roche), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Slide denaturation and hybridization

Metaphase spreads were denatured by heating 200 μL of 70% deionized formamide and 2× SSC solution (pH 7.5) under a coverslip for 2–3 min on a 72°C hotplate. Slides were quenched in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 2 min, followed by dehydration in 90% and 100% ethanol. For each slide, 4–20 ng/μL of nick translated probe was denatured separately for 10 min at 98°C and cooled for 4 min on ice. The subtelomeric BAC probes as well as the chromosome 15 painting probe were preannealed for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of excess mouse COT-1 DNA (Invitrogen). After overnight hybridization at 37°C, slides were washed in 50% formamide and 2× SSC at 42°C, followed by three washes in 2× SSC at room temperature. For the BAC probes, the stringency was increased to three washes in 0.1× SSC at 65°C.

Detection of probes

Slides were blocked with nonfat dry milk (Sigma) solution in 4× SSC and 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma). The biotinylated probe was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated avidin DCS (Vector Laboratories) in 4× SSC, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma). The digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe was detected using the Fluorescent Antibody Enhancer Set for DIG Detection (Roche) and a rhodamine-conjugated anti-DIG antibody according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The signal was amplified with biotinylated goat anti-avidin antibody (Vector Laboratories) diluted in 4× SSC, 1% BSA, and 0.1% Tween 20. Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma) in 2× SSC for 5 min at room temperature and mounted with 2.3% DABCO (Sigma) in 90% glycerol.

Telomere-specific FISH (PNA FISH)

Slides were cross-linked in 4% formaldehyde and PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed three times for 3 min each in 1× PBS, dehydrated through an ascending ethanol series, and air-dried. Slides were overlaid with FITC-conjugated telomere-specific (CCCTAA)3 PNA probe (Panagene) in hybridization mix (70% deionized formamide, 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.2, 0.5% blocking reagent [Roche]) under a coverslip and denatured at 80°C, followed by hybridization for 3 h at room temperature. Slides were washed in 70% formamide, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and 0.1% BSA for 10 min at room temperature, followed by a second wash in 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.08% Tween 20 for 10 min. Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma) and mounted with 2.3% DABCO (Sigma) in 90% glycerol.

Microscopy and imaging

Slides were analyzed on a motorized eight-position stage on an AxioImager M1 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss) and scanned for metaphases with a 10× objective under DAPI excitation using Metafer 4 software (Metasystems). Registered metaphases were rescanned and imaged with a Plan-Apochromat 63× oil immersion objective (NA 1.4), appropriate filter sets (Semrock), and an AxioCam MRm digital camera (Carl Zeiss). Images were histogram-adjusted, pseudo-colored, and analyzed with Isis 5.2.0 software (Metasystems).

Isolation of genomic DNA for genotyping

Preparation of genomic DNA from mouse tail tips for genotyping was performed with a Wizard SV genomic purification system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR genotyping

Five microliters of genomic DNA (∼150 ng) was PCR-amplified in a 50-μL reaction using GoTaq Green Master mix (Promega) and neoR-specific primers. Internal control primers amplifying a sequence from the intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (FABPI) gene were included in the reaction. The primer sequences used were (Stratman et al. 2003) NEO forward, 5′-TGCTCCTGCCGAGAAAGTATCCATCATGGC-3′; NEO reverse, 5′-CGCCAAGCTCTTCAGCAATATCACGGGTAG-3′; FABPI forward, 5′-TGGACAGGACTGGACCTCTGCTTTCCTAGA-3′; and FABPI reverse, 5′-TAGAGCTTTGCCACATCACAGGTCATTCAG-3′.

Cycling conditions were 1 min at 93°C, followed by 30 cycles of 20 sec at 93°C and 3 min at 68°C. The neoR-PCR product resulted in a 380-bp amplimer, whereas the FABPI primers amplified a 194-bp product. PCR products were separated on a 2% TAE agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide (Sigma) and were imaged on a FluorChem 5500 (Alpha Innotech).

Terminal restriction fragment (TRF) analysis

TRFs were prepared by digestion with HinfI and RsaI. TRFs were separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) for 23 h at 6 V/cm with an initial switch time of 1 sec and a final switch time of 6 sec. Gels were dried for 2 h at 60°C, denatured, neutralized, and hybridized overnight to a γ-32P-ATP-labeled (CCCTAA)4 telomeric probe in Church buffer. Gels were washed in 4× SSC and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen overnight prior to visualization using a Typhoon Trio Imager (GE Healthcare).

Acknowledgments

We thank CMRI Bioservices staff for animal husbandry; Melinda Power, Tatiana Radziewic, and Joshua Studdert of the Embryology Unit for assistance with ESC culture and chimera production; Christine Smyth for FACS analysis; and Philip Hodgkin (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia) for advice on splenocyte culture and separation. This work was supported by a Cancer Council NSW program grant, a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia project grant, and the Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Virtual Research Institute of Aging, Japan. P.P.L.T. is an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.205062.112.

References

- Blasco MA, Lee HW, Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp PM, DePinho RA, Greider CW 1997. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 91: 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Englezou A, Gupta J, Bacchetti S, Reddel RR 1995. Telomere elongation in immortal human cells without detectable telomerase activity. EMBO J 14: 4240–4248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Englezou A, Dalla-Pozza L, Dunham MA, Reddel RR 1997. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat Med 3: 1271–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare AJ, Reddel RR 2010. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: Models, mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Genet 11: 319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Khoo CM, Naylor ML, Maser RS, DePinho RA 2003. Telomere-based crisis: Functional differences between telomerase activation and ALT in tumor progression. Genes Dev 17: 88–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T 2004. T-loops and the origin of telomeres. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drost JB, Lee WR 1995. Biological basis of germline mutation: Comparisons of spontaneous germline mutation rates among Drosophila, mouse, and human. Environ Mol Mutagen 25: 48–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham MA, Neumann AA, Fasching CL, Reddel RR 2000. Telomere maintenance by recombination in human cells. Nat Genet 26: 447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH 1989. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337: 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp P, Blasco MA 1999. Telomere length dynamics and chromosomal instability in cells derived from telomerase null mice. J Cell Biol 144: 589–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson JD, Hannay JA, McCarthy SW, Royds JA, Yeager TR, Robinson RA, Wharton SB, Jellinek DA, Arbuckle SM, Yoo J, et al. 2005. A robust assay for alternative lengthening of telomeres in tumors shows the significance of alternative lengthening of telomeres in sarcomas and astrocytomas. Clin Cancer Res 11: 217–225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera E, Martinez C, Blasco MA 2000. Impaired germinal center reaction in mice with short telomeres. EMBO J 19: 472–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenberg JR, Chen XN, Devon KL, Noya D, Oster-Granite ML, Birren BW 1999. Mouse molecular cytogenetic resource: 157 BACs link the chromosomal and genetic maps. Genome Res 9: 514–523 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdorp PM 2009. Telomeres and disease. EMBO J 28: 2532–2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Bailey SM, Okuka M, Muñoz P, Li C, Zhou L, Wu C, Czerwiec E, Sandler L, Seyfang A, et al. 2007. Telomere lengthening early in development. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1436–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyne J, Ratliff RL, Moyzis RK 1989. Conservation of the human telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n among vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 7049–7053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish TA, Greider CW 2009. Short telomeres initiate telomere recombination in primary and tumor cells. PLoS Genet 5: e1000357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni A, Neumann AA, Hills M, Reddel RR 2009. Telomere elongation involves intra-molecular DNA replication in cells utilizing alternative lengthening of telomeres. Hum Mol Genet 18: 1017–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane JP, Sabatier L, Marder BA, Morgan WF 1994. Telomere dynamics in an immortal human cell line. EMBO J 13: 4953–4962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A. 2003 Manipulating the mouse embryo: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Niida H, Shinkai Y, Hande MP, Matsumoto T, Takehara S, Tachibana M, Oshimura M, Lansdorp PM, Furuichi Y 2000. Telomere maintenance in telomerase-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells: Characterization of an amplified telomeric DNA. Mol Cell Biol 20: 4115–4127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrem K, Colgin LM, Neumann AA, Yeager TR, Reddel RR 2001. Coexistence of alternative lengthening of telomeres and telomerase in hTERT-transfected GM847 cells. Mol Cell Biol 21: 3862–3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MK, Friedman C, Parghi SS, Linardopoulou EV, Hsu L, Trask BJ 2007. Elevated rates of sister chromatid exchange at chromosome ends. PLoS Genet 3: e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Bacchetti S 1997. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur J Cancer 33: 787–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratman JL, Barnes WM, Simon TC 2003. Universal PCR genotyping assay that achieves single copy sensitivity with any primer pair. Transgenic Res 12: 521–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano S, Okochi H 2005. Long-term culture of adult murine epidermal keratinocytes. Br J Dermatol 153: 1101–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalzman M, Falco G, Sharova LV, Nishiyama A, Thomas M, Lee SL, Stagg CA, Hoang HG, Yang HT, Indig FE, et al. 2010. Zscan4 regulates telomere elongation and genomic stability in ES cells. Nature 464: 858–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Yi X, Wright WE, Shay JW 2002. Human telomerase can immortalize Indian muntjac cells. Exp Cell Res 281: 63–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]