Abstract

Trends in utilization and outcomes after autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for Burkitt Lymphoma (BL) were analyzed in 241 recipients reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) between 1985 and 2007. The autologous HCT cohort had a higher proportion with chemotherapy sensitive disease, peripheral blood grafts and HCT in first complete remission (CR1). The use of autologous HCT has declined over time with only 19% done after 2001. Overall survival (OS) at 5 years for the autologous cohort was 83% for those in CR1, and 31% for non-CR1 recipients. Corresponding progression free survival (PFS) was 78% and 27%, respectively. After allogeneic HCT, OS at 5 years was 53% and 20% for the CR1 and non-CR1 cohorts while PFS was 50% and 19%, respectively. The most common cause of death was progressive lymphoma. Allogeneic HCT performed in a higher risk subset (per NCCN guidelines) resulted in a 5 year PFS of 27%. Autologous HCT, resulted in a 5 year PFS of 44% in those transplanted in second CR.

Keywords: alloHCT, autoHCT, Burkitt lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is an aggressive but highly curable mature B cell, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) composed of monomorphic, medium-sized B cells with basophilic cytoplasm and numerous mitotic figures. Chromosomal translocation leading to overexpression of MYC, a growth fraction of nearly 100% and a common predilection for extra nodal disease sites are consistent features 1,2. Median age at diagnosis of BL is 45 years and 30% of patients are over the age of 60 years 3. Although 3 clinical variants of BL (endemic, sporadic and immunodeficiency associated BL) have been distinguished, sporadic BL accounts for 1–2% of all adult lymphomas in the US and Western Europe. Higher level evidence based therapeutic recommendations are lacking in adult BL because of its relative rarity in adults, lack of randomized trials in adult BL 3 and the variable pathological definitions used over time 4. However with modern chemotherapy regimens, cure rates have increased with 3 year survival varying between 50 to 90% 5,6. According to NCCN consensus guidelines, normal LDH, fully resected stage 1 disease or a single mass <10 cm represent low risk disease and all other patients have high risk disease7. These guidelines recommend no preferred standard approaches to those with disease relapsing after modern induction regimens and these patients represent the highest risk subset.

In the 1980s and 1990s, BL was treated with regimens used for other NHL subtypes with inferior remission rates and survival. Due to these poor results with conventional chemotherapy, HCT was used in high-risk patients as consolidation therapy in first complete remission (CR1) or after relapse although very few published reports are available. Introduction of contemporary intensive multi agent therapy with central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis had dramatic results with 2 year disease free survivals (DFS) of 75-80% in pediatric patients with advanced disease 8. The use of such brief, high intensity regimens in adults in combination with the anti CD20 antibody Rituximab has resulted in dramatic improvement, with reported 3 year survival close to 90% in some series 6. It is hard to evaluate the role of autologous or allogeneic HCT in the era of modern effective chemotherapy regimens for BL. We analyzed trends in utilization and outcomes of autologous and allogeneic HCT for BL over the past 2 decades and the current utilization of HCT in BL so that indirect comparison can be made to current chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Source

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) is a voluntary group of more than 500 transplant centers worldwide. Participating centers register basic information on all consecutive HCTs to a Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Detailed demographic and clinical data are collected on a representative sample of registered patients using a weighted randomization scheme. Compliance is monitored by on site audits. Patients are followed longitudinally, with yearly follow-up. Computerized checks for errors, physician reviews of submitted data and on-site audits of participating centers ensure the quality of data.

Patients

The study population included all persons with BL or Burkitt leukemia receiving a HCT reported to the CIBMTR between 1985 and 2007. Because of their shared immunophenotypic and cytogenetic features BL and Burkitt leukemia (previously known as L3 acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL] in the French–American–British [FAB] classification system) were analyzed as a combined group as has been performed in most modern series 5,9. Central pathology review was not performed. HIV positive patients were included in the analysis (n=4).

Study Endpoints

Outcomes studied included non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression / relapse, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). NRM was defined as death within 28 days post-transplant or death without lymphoma progression. Progression/relapse was defined as progressive lymphoma after HCT (≥ 28 days) or lymphoma recurrence after a complete remission. For PFS, subjects were considered treatment failures at the time of lymphoma progression or death from any cause. OS interval was defined as time from the date of transplant to the date of death with patients censored at the time of last contact. Other outcomes analyzed included acute- and chronic graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD and cGVHD) and cause of death (COD). aGVHD and cGVHD were defined and graded using established criteria. Disease status prior to HCT was defined as follows.Primary Induction Failure (PIF) cohort was defined as patients who never achieved complete remission (but cold be with partial remission, stable or progressive disease on treatment). Chemosensitive relapse was defined as relapse with a partial response to therapy (≥ 50% reduction in bidimensional diameter of all disease sites with no new sites of disease). Chemoresistant relapse was defined as relapsed disease with a partial response to salvage therapy (<50% reduction in diameter of all disease sites or development of new disease sites).

Statistical Analysis

Patient-, disease-, and transplant-related variables and outcomes were described in 3 cohorts – recipients of autologous HCT or allogeneic HCT from matched sibling or unrelated / mismatched related donors. Univariate probabilities of developing aGVHD and cGVHD, NRM, and lymphoma progression were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks. Probabilities of OS and PFS were calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimator 10. Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated with a log transformation. Multivariate analyses were not performed because of the imbalance in baseline characteristics of the cohorts and the changes in BL management over the period studied.

RESULTS

Patient, Disease-, and Transplant-Related Variables

Between 1985 and 2007, 249 patients received HCT for BL. Three patients were excluded from analysis due to inadequate data collection and 5 syngeneic twin transplant recipients were excluded. Out of the 241 patients, 113 patients received an autologous HCT and 128 received an allogeneic HCT. Completeness of follow-up (the ratio of the sum of the observed follow-up time to the sum of the potential follow-up time) for all subjects was 86% for both cohorts.

Table 1 describes subject-, disease- and transplant related variables of three cohorts analyzed 113 autologous HCT recipients, 80 HLA-identical sibling HCT recipients and 48 unrelated or mismatched related donor grafts recipients (including 8 cord blood graft recipients). The autologous cohort was older compared with the HLA identical sibling and unrelated/ mismatched related cohorts (P < 0.001). Majority of patients had a pre-transplant Karnofsky/Lansky performance score (KPS) of 90 or higher. Median time from diagnosis to transplant was 7 months (2–74 months) in the autologous cohort, 6 months (1–29 months) in HLA-identical sibling and 9 months (1–113 months) in the unrelated / mismatched related cohort.

Table 1.

Characteristics of recipients of autologous, HLA-identical sibling or unrelated/mismatched related donor HCT for BL

| Autologous N (%) |

HLA-identical sibling N (%) |

Unrelated/ mismatched related N (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 113 | 80 | 48 | |

| Age, median (range), years | 31 (5–76) | 24 (3–55) | 22 (2–54) | <0.001 |

| Age at transplant | 0.005 | |||

| <10 yrs | 6 (5) | 10 (13) | 10 (21) | |

| 10–19 yrs | 26 (23) | 22 (28) | 12 (25) | |

| 20–29 yrs | 21 (19) | 21 (26) | 10 (21) | |

| 30–39 yrs | 20 (18) | 15 (19) | 8 (17) | |

| 40–49 yrs | 14 (12) | 7 (9) | 6 (13) | |

| 50–59 yrs | 12 (11) | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | |

| ≥60 yrs | 14 (12) | 0 | 0 | |

| Male Sex | 79 (70) | 53 (66) | 39 (81) | 0.183 |

| Karnofsky score at HCT <90% | 32 (28) | 29 (36) | 23 (48) | 0.184 |

| Interval from diagnosis to transplant, median (range), months | 7 (2–74) | 6 (1–29) | 9 (1–113) | 0.002 |

| Disease stage at diagnosis | 0.076 | |||

| I–II | 34 (30) | 14 (18) | 19 (40) | |

| III–IV | 76 (67) | 50 (63) | 26 (54) | |

| Unknown | 3 (3) | 16 (20) | 3 (6) | |

| Number of prior chemotherapy lines | 0.032 | |||

| 1 | 26 (23) | 9 (11) | 4 (8) | |

| 2 | 42 (37) | 23 (29) | 17 (35) | |

| 3 or more | 25 (22) | 18 (23) | 22 (46) | |

| Missing | 20 (18) | 30 (38) | 5 (10) | |

| Rituxan prior to Tx | 6 (5) | 11 (14) | 12 (25) | 0.002 |

| Methotrexate or Cytarabine prior to HCT | 46(32) | 28(35) | 33(69) | <0.001 |

| Reduced Intensity Conditioning | NA | 10 (13) | 4 (8) | 0.556 |

| Conditioning regimen details-allogeneic group | NA | 0.609 | ||

| Cy+TBI | 52 (65) | 32 (67) | ||

| Bu+Cy | 12 (15) | 5 (10) | ||

| CY + Etoposide based | 6 (8) | 1 (2) | ||

| Others (Low dose TBI, BU, MEL) | 10(12) | 10(20) | ||

| Conditioning regimen-autologous group | NA | NA | NA | |

| TBI-based | 30 (27) | |||

| BEAM and similar | 62 (55) | |||

| CBV or similar | 12 (11) | |||

| BuMEL/BuCy | 6 (5) | |||

| Others | 3 (3) | |||

| Extranodal involvement at diagnosis | 80 (71) | 40 (50) | 35 (73) | <0.001 |

| Marrow involvement at diagnosis | 25 (22) | 17 (21) | 13 (27) | 0.011 |

| CNS involvement at diagnosis | 13 (12) | 10 (13) | 5 (10) | 0.398 |

| Disease status prior to transplant | 0.001 | |||

| PIF sensitive | 13 (12) | 8 (9) | 8 (17) | |

| PIF resistant | 5 (4) | 3 (4) | 4 (8) | |

| CR1 | 48 (42) | 27 (34) | 3 (6) | |

| REL sensitive | 17 (15) | 3 (4) | 6 (13) | |

| REL resistant | 3 (3) | 4 (5) | 6 (13) | |

| CR2 or beyond | 19 (17) | 23 (29) | 16 (33) | |

| Unknown | 8 (7) | 12 (15) | 5 (10) | |

| Chemotherapy sensitivity at transplant | 0.011 | |||

| Sensitive | 97 (86) | 62 (78) | 34 (71) | |

| Graft type | <0.001 | |||

| Bone marrow | 31 (27) | 55 (69) | 32 (67) | |

| Peripheral blood | 82 (73) | 25 (31) | 8 (17) | |

| Cord blood | 0 | 0 | 8 (17) | |

| Year of HCT | <0.001 | |||

| 1985–1988 | 1 (1) | 17 (21) | 0 | |

| 1989–1992 | 21 (19) | 10 (13) | 2 (4) | |

| 1993–1996 | 31 (27) | 16 (20) | 7 (15) | |

| 1997–2000 | 38 (34) | 16 (20) | 9 (19) | |

| 2001–2004 | 16 (14) | 15 (19) | 19 (40) | |

| 2005–2007 | 6 (5) | 6 (8) | 11 (23) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | NA | <0.001 | ||

| T-cell depletion | 13 (16) | 5 (10) | ||

| FK506+MTX+-other | 4 (5) | 16 (33) | ||

| CsA+MTX+-other | 41 (51) | 27 (56) | ||

| Median follow-up of survivors, months | 79 (9–222) | 56 (4–233) | 50 (26–160) |

Abbreviations NA = not applicable; CR = complete remission; PIF = primary induction failure; REL = relapse; CY = cyclophosphamide, GVHD = graft versus host disease; MTX = methotrexate; CsA = cyclosporine; FK506 = tacrolimus.

The majority of patients across cohorts had Stage III or IV BL at diagnosis. Autologous HCT cohort tended to have fewer lines of pre-HCT chemotherapy and more recipients transplanted in CR1. Central nervous system involvement was similar across cohorts. Extranodal involvement at diagnosis was 71% in the autologous, 50% in the HLA identical sibling and 73% in the unrelated / mismatched related cohorts respectively. At the time of HCT, 42% of the autologous, 34% of the HLA identical sibling and 6% of the unrelated / mismatched related cohorts were in first complete remission (CR1). Proportion of patients with sensitivity to chemotherapy at HCT was 86% in the autologous, 78% of the matched sibling allogeneic and 71% of the unrelated / mismatched related cohorts. The commonest conditioning regimen prior to autologous HCT was BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine and Melphalan) in 55%. There was limited use of reduced intensity conditioning (10%) prior to allogeneic HCT. Among myeloablative regimens, cyclophosphamide (Cy) and TBI (Cy-TBI) and busulfan (Bu) and Cy (Bu-Cy) accounted for > 75%. There was a substantial decline in the numbers of autologous HCT performed in recent years with only 19% being performed after 2000. Similarly there was increasing use of non sibling donor allografts in recent years (63% after 2000).

Outcomes

Outcomes after HCT are summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Outcomes after HCT for BL

| Autologous (N =113) |

HLA-identical siblings (N=80) |

Unrelated/ mismatched related (N=48) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome event | Prob (95% CI) | Prob (95% CI) | Prob (95% CI) | P-valuea |

| 100 day mortality | 4 (1–8) | 20 (12–30) | 19 (9–31) | <0.001 |

| Acute GVHD @ 100 days, grades (2–4) | NA | 35 (25–46) | 53 (39–67) | 0.044 |

| Acute GVHD @ 100 days, grades (3–4) | NA | 15 (8–24) | 35 (23–49) | 0.010 |

| Chronic GVHD | NA | |||

| @ 1 year | 17 (9–26) | 16 (7–28) | 0.873 | |

| @ 3 years | 18 (10–28) | 16 (7–28) | 0.734 | |

| @ 5 years | 18 (10–28) | 16 (7–28) | 0.734 | |

Abbreviations ANC = neutrophil recovery; TRM = treatment-related mortality; PFS = progression-free survival; PROB = probability; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3.

Outcomes of patients in CR1 versus beyond CR1

| Autologous | Allogeneic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR1 | Non-CR1 | CR1 | Non-CR1 | ||||||

| Outcome event | N | Prob (95% CI) | N | Prob (95% CI) | N | Prob (95% CI) | N | Prob (95% CI) | P-valuea |

| NRM | 48 | 57 | 30 | 80 | |||||

| @ 1 year | 2 (0–10) | 9 (3–18) | 23 (10–39) | 27 (17–37) | <0.001 | ||||

| @ 5 years | 4 (1–13) | 12 (5–22) | 23 (10–39) | 30 (20–40) | <0.001 | ||||

| Progression/Relapse | 48 | 57 | 30 | 80 | |||||

| @ 1 year | 13 (5–24) | 51 (38–63) | 24 (10–39) | 51 (40–62) | <0.001 | ||||

| @ 5 years | 18 (8–30) | 61 (47–73) | 27 (13–44) | 51 (40–62) | <0.001 | ||||

| PFS | 48 | 57 | 30 | 80 | |||||

| @ 1 year | 85 (71–93) | 40 (27–52) | 53 (34–69) | 22 (14–32) | <0.001 | ||||

| @ 5 years | 78 (63–88) | 27 (16–40) | 50 (30–66) | 19 (11–29) | <0.001 | ||||

| Overall survival | 48 | 57 | 30 | 81 | |||||

| @ 1 year | 85 (72–93) | 42 (29–54) | 53 (34–69) | 23 (14–33) | <0.001 | ||||

| @ 5 years | 83 (69–91) | 31 (19–44) | 53 (34–69) | 20 (12–30) | <0.001 | ||||

Abbreviations NRM = Non relapse mortality; PFS = progression-free survival; PROB = probability; CI = confidence interval.

Table 4.

Outcomes of patients in first (CR1) versus a later complete remission (CR ≥ 2) versus those not in CR

| Autologous | Allogeneic | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR1 | CR ≥2 | Non-CR | CR1 | CR ≥2 | Non-CR | ||||||||

| Outcome event |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

P-valuea |

| Progression/ | 48 | 19 | 38 | 30 | 39 | 41 | |||||||

| Relapse | |||||||||||||

| @ 1 year | 13 (5–24) | 44 (21–65) | 55 (38–69) | 24 (10–39) | 49 (32–63) | 54 (37–67) | <0.001 | ||||||

| @ 5 years | 18 (8–30) | 50 (26–70) | 67 (49–79) | 27 (13–44) | 49 (32–63) | 54 (37–67) | <0.001 | ||||||

| PFS | 48 | 19 | 38 | 30 | 39 | 41 | |||||||

| @ 1 year | 85 (71–93) | 50 (26–70) | 34 (20–49) | 53 (34–69) | 30 (17–45) | 14 (6–27) | <0.001 | ||||||

| @ 5 years | 78 (63–88) | 44 (21–65) | 19 (9–34) | 50 (30–66) | 27 (15–42) | 11 (4–24) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Overall | |||||||||||||

| survival | 48 | 19 | 38 | 30 | 39 | 42 | |||||||

| @ 1 year | 85 (72–93) | 53 (29–72) | 37 (22–52) | 53 (34–69) | 31 (17–45) | 16 (6–28) | <0.001 | ||||||

| @ 5 years | 83 (69–91) | 53 (29–72) | 22 (10–36) | 53 (34–69) | 28 (15–43) | 12 (4–25) | <0.001 | ||||||

Abbreviations TRM = treatment-related mortality; PFS = progression-free survival; PROB = probability; CI = confidence interval.

Probabilities of treatment-related mortality and progression/relapse were calculated using the cumulative incidence estimate. Progression-free survival and overall survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimate.

Non relapse mortality (NRM)

Day-100 mortality rates were 4% for the autologous cohort, 20% for the HLA identical sibling cohort and 19% (P < 0.001) for unrelated / mismatched related cohort (Table 2). Cumulative incidence estimates of NRM at 5 years were 8% (95% CI 3-14) in the autologous cohort, 28% (95% CI 19-38) in the HLA-identical sibling cohort and 30% (95% CI 18-44) in the unrelated/ mismatched related cohort (P < 0.001). For those receiving autologous HCT in first remission (CR1) the 5 yr NRM was 4% (95% CI 1-13) vs. 12% (95% CI 5-22) for those not in CR1 (P < 0.001; Table 3). Similar comparison in the allogeneic cohort indicated a 5 yr NRM of 23% (95% CI 10-39) for those in CR1 vs. 30% (95% CI 20-40) for those not in CR1 (P < 0.001).

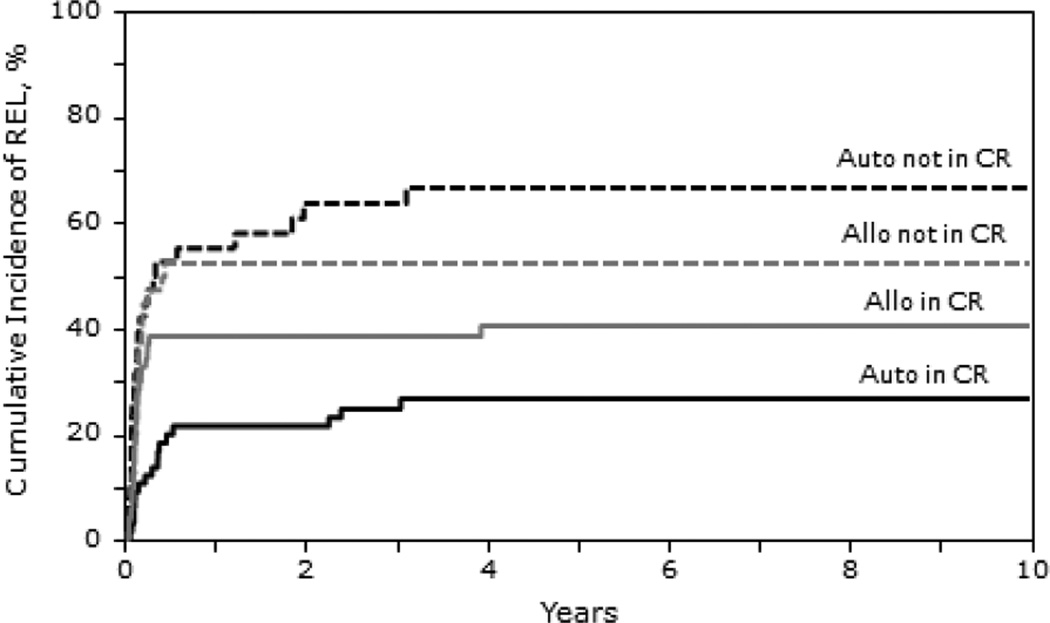

Progression/Relapse

The 1,3 and 5-year probability of progression were similar in all the cohorts; at 5 years it was 44% in the autologous cohort (95% CI 35-53), 42% (95% CI 31-53) in the HLA identical sibling cohort and 48% (95% CI 34-62; p=0.811) in the unrelated / mismatched related cohort. For autologous HCT recipients treated in CR1 vs. those beyond CR1, the progression rate was 18% (95% CI 8-30) and 61% (95% CI 47-73), respectively. For allogeneic recipients, progression risk at 5 years was 27% (95% CI 13-44) for those in CR1 vs. 51% (95% CI 40-62; p<0.001) in recipients beyond CR1. Patients in later complete remission (CR ≥2) receiving autologous or allogeneic HCT had a higher incidence of lymphoma progression at 5 years (50% and 49%, respectively) compared with those transplanted in CR1 ((P < 0.001; Table 4). For those not in CR at HCT the incidence of lymphoma progression at 5 years was 67% for the autologous and 54% for allogeneic cohorts.

PFS

The 1,3 and 5 year PFS estimates for those receiving autologous HCT were 60% (95% CI 51-69) , 53% (95% CI 44-62) and 48% (95% CI 39-58) respectively. Similar 1, 3 and 5 year PFS estimates for the HLA identical sibling cohort were 33% (95% CI 23-44), 31% (95% CI 22-42) and 30% (95% CI 20-41) respectively. In the unrelated/ mismatched related cohort, 1,3 and 5 year PFS estimates were 24% (95% CI 13-38) , 22% (95% CI 12-35) and 22% (95% CI 12-35) respectively (P < 0.001).

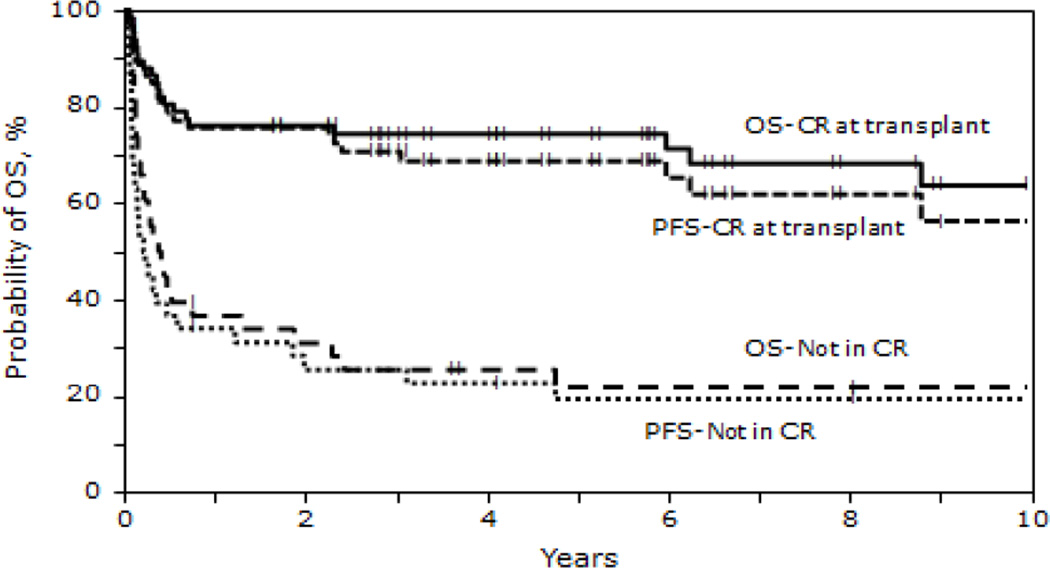

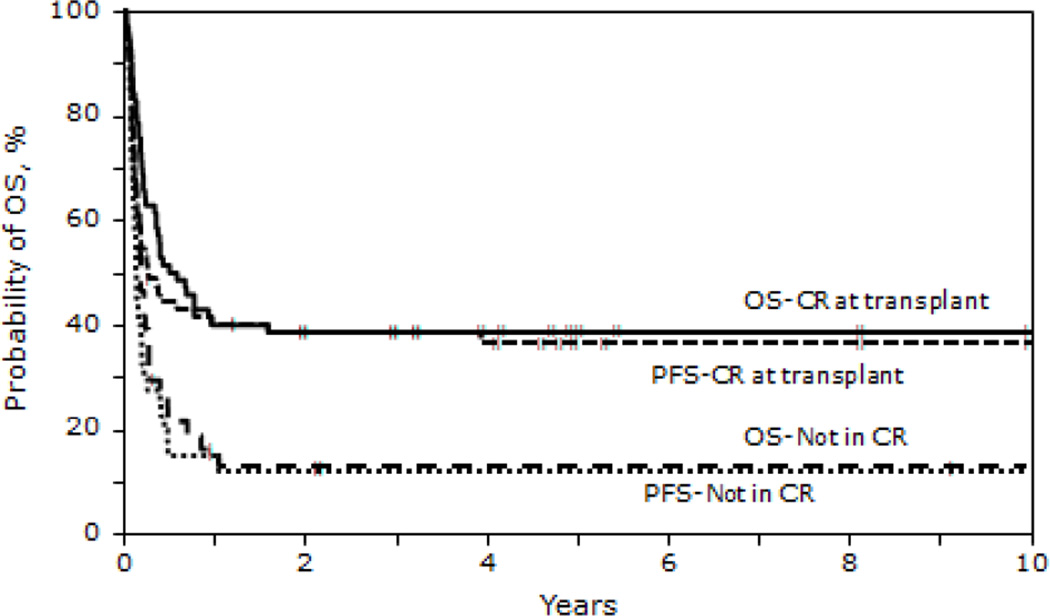

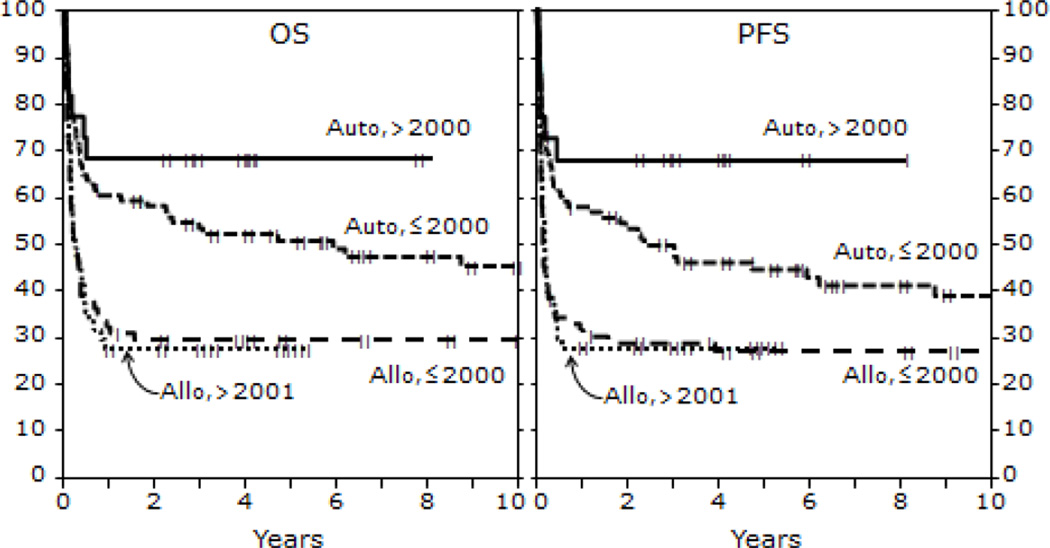

The 5 - year probability of PFS for recipients in CR1 receiving autologous HCT was 78% (95% CI 63-88) vs. 27% (95% CI 16-40) in recipients beyond CR1. For recipients of allogeneic HCT, 5 year PFS was 50% (95% CI 30-66) for those in CR1 vs. 19% (95% CI 11-29) in non CR1 recipients (P < 0.001). Patients in a second or subsequent CR receiving autologous or allogeneic HCT had inferior 5 year PFS 44% (95% CI 21-65) and 27%, (95% CI 15-42) respectively (Table 4). PFS at 5 years for those not in CR at HCT was 19% (95% CI 9-34) for autologous and 11% (95% CI 4-24) for allogeneic HCT cohorts (P < 0.001). Survival (Figures 1, 2 and 3)

Figure 1.

Probability of OS and PFS after autologous transplantation for BL by disease status

Figure 2.

Probability of OS and PFS after allogeneic transplantation for BL by disease status

Figure 3.

Probability of OS and PFS after HCT for BL by year of HCT

OS at 1,3 and 5 years for those receiving autologous HCT were 62% (95% CI 53-71), 57% (95% CI 48-66) and 54% (95% CI 44-63) respectively. OS at 1, 3 and 5 years for the HLA identical sibling cohort were 33% (95% CI 23-44), 31% (95% CI 22-43) and 32% (95% CI 22-43) respectively. In the unrelated/ mismatched related cohort, 1,3 and 5 year OS was 25% (95% CI 14-38) , 23% (95% CI 12-36) and 23% (95% CI 12-36) respectively (P < 0.001). The 5 - year probability of OS for recipients in CR1 receiving autologous HCT was 83% (95% CI 69-91) vs. 31% (95% CI 19-44) in non CR1 recipients. For recipients of allogeneic HCT, 5 year OS was 53% (95% CI 34-69) for those in CR1 vs. 20% (95% CI 12-30) in non CR1 recipients (P < 0.001). Patients in a second or subsequent CR receiving autologous or allogeneic HCT had inferior 5 year OS 53% (95% CI 29-72) and 28% (95% CI 15-43) respectively (Table 4). OS at 5 years for those not in CR at HCT was 22% (95% CI 10-36%) for autologous and 12% (95% CI 4-25%) for allogeneic HCT cohorts (P < 0.001; Figures 1 and 2). Survival of patients transplanted before and after 2000 is shown in Figure 3.

GVHD

Cumulative incidences of aGVHD (≥ grade 2) in the allogeneic cohort by day 100 were 35% (95% CI 25-46) in the HLA-identical sibling cohort and 53% (95% CI 39-67) in the unrelated or mismatched related cohort (P = .04). Cumulative incidences of aGVHD (≥ grade 3) in the allogeneic cohort by day 100 were 15% (95% CI 8-24) in the HLA-identical sibling cohort and 35% (95% CI 23-49) in the unrelated or mismatched related cohort (P = .01). The incidence of cGHVD at 5 years was 18% (95% CI 10-28) in the HLA-identical sibling cohort and 16% (95% CI 7-28; P = .73) in the unrelated / mismatched related cohort (Table 2). Seven HLA-identical sibling patients had limited chronic GVHD and 4 extensive GVHD. All five unrelated matched patients had extensive chronic GVHD.

Causes of Death

The majority of deaths - 44 in the autologous cohort and 61 in the allogeneic cohort - were attributed to relapsed BL. Causes of death are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Causes of death

| Autologous | HLA-identical sibling |

Unrelated/ mismatched related |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Number of deaths | 56 | 54 | 37 |

| Primary disease | 44 (79) | 39 (72) | 22 (59) |

| GVHD | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Pulmonary syndrome | 0 | 3 (6) | 3 (8) |

| Infection | 2 (4) | 4 (7) | 2 (5) |

| Organ Failure | 0 | 3 (6) | 5 (14) |

| Others* | 9 (16) | 2 (4) | 4 (11) |

Abbreviation GVHD = graft versus host disease

Others include: new malignancy (n=3), hemorrhage (n=1), spongiform disorder brain (n=1), bilateral pneumonia ARDS (n=1), not specified (n=9)

DISCUSSION

This analysis was designed to examine the changing role of HCT in the era of modern chemotherapy for BL and to define the outcomes after HCT. The trends identified in this study confirm the declining use of HCT in BL since the advent of high intensity chemotherapy regimens and the availability of rituximab. However patients who relapse following initial response to therapy have an extremely poor prognosis and there is a paucity of data to guide the treatment approach of patients with relapsed or refractory BL. A retrospective registry analysis of 117 adult patients who underwent autologous HCT for BL included 47 patients with relapsed or resistant disease 11. OS rates at 3 years were 72, 37 and 7 percent for those transplanted in CR1, chemotherapy sensitive relapse and chemotherapy resistant relapse, respectively. Our analysis showed a 5 year OS for autologous HCT of 83% for those in first CR, 53% for those in a subsequent CR and 22% for those not in CR. The allogeneic HCT cohort in our analysis had 5 year survival rates of 53% for patients in first CR, 28% for those in a subsequent CR and 12% for those not in CR. The allogeneic cohort was comprised of patients who were younger (< 40 years) but had a higher proportion with chemotherapy resistant disease and more lines of prior therapy compared to the autologous cohort. Therefore the autologous and allogeneic cohorts are not directly comparable. We could not with review of registry data glean reason by centers on the choice of transplant type. A multivariate analysis was not performed because of the major baseline imbalance between groups and the long time period under study during which time transplant practice changed substantially. The choice of allogeneic vs. autologous HCT is guided by factors such as chemotherapy sensitivity, donor availability, disease status prior to autologous collection and status of peripheral blood and marrow involvement with BL. In the era of modern chemotherapy, there was a diminishing role for autologous HCT as a consolidative measure in first CR while allogeneic HCT seems to be reserved for patients with advanced disease. Autologous HCT in the post-relapse setting resulted in a PFS of 44% at 5 years for those achieving a subsequent CR prior to transplant.

Unfortunately the high NRM and high risk of relapse in the first year lead to substantial early mortality after allogeneic HCT. A clear graft vs. tumor effect cannot be determined from these data. The lack of relapse could represent a graft vs. tumor effect or could simply represent that relapse is unlikely because the patient mostly at risk died early.

Autologous HCT in CR1 in the era before modern intense regimens for BL offered seem to have equivalent survival results compared to the reports for dose intense modern regimens such as CODOX-M (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high dose methotrexate) / IVAC (Ifosfamide, etoposode and high dose cytarabine) and R-hyperCVAD (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone alternating with high dose methotrexate and cytarabine) 6,12. With the CODOX-M/ IVAC regimen, 2 year EFS was 50-60% in high risk patients 13,14. These intense chemotherapy regimens6,12–14 are also associated with a lower NRM, usually less than 5%, than those reported for allogeneic HCT, but no necessarily autologous HCT. Notably in the current analysis, patients receiving autologous HCT were of high risk with a substantial proportion with extranodal (70%) or CNS (12%) involvement. The durability of benefit from HCT demonstrated in this analysis is longer than the follow up duration in most reports of contemporary chemotherapy regimens. The use of autologous HCT after a shortened course of contemporary aggressive chemotherapy may remain an interesting approach that could be tested in prospective trials.

Given these data, autologous HCT in CR1 is unlikely to offer additional advantage over current dose intense chemotherapy regimens. The declining use of HCT for BL in the setting of first CR is justified as the historical survival outcomes from this study are not superior to reported outcomes after current non-transplant approaches, particularly considering selection bias that might have influenced decision making. However HCT seems not to be inferior given the long term follow up data. In patients with advanced BL, autologous HCT may remain a salvage option provided subsequent disease control is obtained with second line chemotherapy.

Allogeneic HCT was mostly performed for those with higher risk / advanced BL and resulted in long term PFS for a minority of patients with relapses and mortality occurring mainly within the first year after HCT. HCT for BL will admittedly be hard to study in trials given the rarity of the disease and the good outcomes with upfront chemotherapy. Based on these results however, HCT should continue to be considered for select patients.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of relapse after autologous and allogeneic transplantation for BL by disease status.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would also like to give special thanks to Mahmoud Aljurf, MD, Brandon M. Hayes-Lattin, MD,, Luis M. Isola, MD, Chul Won Jung, MD, Armand Keating, MD, Ginna G. Laport, MD, Dipnarine Maharaj, MD, James R. Mason, MD, Philip L. McCarthy, MD, Arturo Molina, MD, MS, FACP and Julie M. Vose, MD

SUPPORT

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24- CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH234200637015C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Allos, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Angioblast; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Buchanan Family Foundation; CaridianBCT; Celgene Corporation; Cell Genix, GmbH; Children’s Leukemia Research Association; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Histo Genetics, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; Milliman USA, Inc.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Remedy MD; Sanofi; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; Stem Cyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stem soft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; Tarix Pharmaceuticals; Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; THERAKOS, Inc.; and Well point, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Blum KA, Lozanski G, Byrd JC. Adult Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma. Blood. 2004;104:3009–3020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yustein JT, Dang CV. Biology and treatment of Burkitt's lymphoma. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:375–381. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3281bccdee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly JL, Toothaker SR, Ciminello L, et al. Outcomes of patients with Burkitt lymphoma older than age 40 treated with intensive chemotherapeutic regimens. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9:307–310. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.n.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linch DC. Burkitt lymphoma in adults. Br J Haematol. 156:693–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizzieri DA, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Intensive chemotherapy with and without cranial radiation for Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma: final results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9251. Cancer. 2004;100:1438–1448. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas DA, Faderl S, O'Brien S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with hyper-CVAD plus rituximab for the treatment of adult Burkitt and Burkitt-type lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;106:1569–1580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Accessed [September 15, 2012]];The NCCN GUIDELINE Practice Guidelines in Oncology – v.3.2012. © 2012 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. Available at http://www.nccn.org. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to www.nccn.org. 2012.

- 8.Aldoss IT, Weisenburger DD, Fu K, et al. Adult Burkitt lymphoma: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:1508–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patte C, Auperin A, Michon J, et al. The Societe Francaise d'Oncologie Pediatrique LMB89 protocol: highly effective multiagent chemotherapy tailored to the tumor burden and initial response in 561 unselected children with B-cell lymphomas and L3 leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:3370–3379. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan E. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweetenham JW, Pearce R, Taghipour G, et al. Adult Burkitt's and Burkitt-like non-Hodgkin's lymphoma--outcome for patients treated with high-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in first remission or at relapse: results from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2465–2472. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magrath IT, Haddy TB, Adde MA. Treatment of patients with high grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas and central nervous system involvement: is radiation an essential component of therapy? Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;21:99–105. doi: 10.3109/10428199609067586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mead GM, Barrans SL, Qian W, et al. A prospective clinicopathologic study of dose-modified CODOX-M/IVAC in patients with sporadic Burkitt lymphoma defined using cytogenetic and immunophenotypic criteria (MRC/NCRI LY10 trial) Blood. 2008;112:2248–2260. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mead GM, Sydes MR, Walewski J, et al. An international evaluation of CODOX-M and CODOX-M alternating with IVAC in adult Burkitt's lymphoma: results of United Kingdom Lymphoma Group LY06 study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1264–1274. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]