Abstract

Introduction

Neutropenic enterocolitis (NEC) can be a life-threatening complication of chemotherapy in leukemic patients. Early diagnosis and treatment is therefore crucial.

Methods

A 38-year-old woman with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chemotherapy-induced neutropenia suddenly developed symptoms suspicious of NEC. Transabdominal ultrasound showed features consistent with NEC, later confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan.

Results

The patient was scanned using portable ultrasound (US) equipment (Esaote My Lab 25). US findings showed involvement of the cecum, appendix, ascending colon and proximal middle transverse colon, with features resembling gas containing fissures within the colon wall itself. The risk of colon rupture was confirmed by CT scan. The patient underwent successful hemicolectomy after intravenous treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), platelets and fresh frozen plasma transfusion.

Discussion

A prompt bedside US examination upon development of symptoms allowed an early diagnosis of NEC and identified features consistent with imminent colon wall rupture, shifting the management of this life-threatening complication from medical to surgical. Multidisciplinary intervention was crucial for a successful hemicolectomy in a severely affected neutropenic patient.

Keywords: Neutropenic, Enterocolitis, Leukemia, Ultrasound sonography, Hemicolectomy

Sommario

Introduzione

La tiflite (Neutropenic enterocolitis, NEC) può essere una complicanza fatale in pazienti affetti da leucemia e sottoposti a chemioterapia. Una precoce diagnosi e terapia sono essenziali.

Metodi

Una donna di 38 anni affetta da leucemia linfoblastica acuta durante la neutropenia indotta dalla chemioterapia improvvisamente ha sviluppato segni e sintomi compatibili con NEC. Una ecografia addominale ha mostrato segni di NEC confermati successivamente con la TC.

Risultati

È stato utilizzato un ecografo portatile (Esaote My Lab 25). Segni ecografici di coinvolgimento intestinale sono stati trovati a carico del cieco, appendice, colon ascendente e della parte prossimale del colon trasverso, con aspetti compatibili con presenza di gas nella parete stessa. Il rischio di perforazione del colon è stato confermato con l'esame TC. La paziente è stata sottoposta con successo a una emicolectomia dopo aver ricevuto antibiotici per endovena, G-CSF, e trasfusione di granulociti, piastrine e plasma fresco congelato.

Discussione

Una ecografia eseguita precocemente al letto del paziente appena sono comparsi i sintomi ha permesso non solo di identificare segni compatibili con NEC, ma di identificare segni di possibile imminente rottura della parete, cambiando il trattamento da medico a chirurgico. Un intervento multidisciplinare è stato essenziale permettendo alla paziente di essere sottoposta con successo a una emicolectomia durante neutropenia.

Introduction

Neutropenic enterocolitis (NEC) is a life-threatening complication in patients affected by leukemia and solid tumors treated with chemotherapy [1]. It can also develop in patients with aplastic anemia or cyclic neutropenia who have not received cytotoxic treatment [2]. It is a necrotizing inflammatory disease of the ileocecal region. Clinically it is characterized by neutropenia, fever and abdominal pain with or without diarrhea. The pathogenic mechanisms leading to NEC are probably multifactorial such as neutropenia, destruction of the normal mucosal architecture due to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, possible coexistent leukemic or lymphomatous infiltrates, thrombocytopenia related intramural hemorrhage and shift in the normal gastrointestinal microbial flora due to antibiotics, antifungals and nosocomial colonization by hospital flora [3]. The cecum is almost always affected, but the terminal ileum as well as other parts of the small bowel and right and left colon can also be involved in NEC. Macroscopically the involved bowel segments show edematous and thickened walls, with varying degrees of ulceration and hemorrhage. Perforation occurs in 5–10% of cases. Early diagnosis is crucial in order to start conservative medical management which seems to be the best strategy in most cases [4].

Materials and methods

A 38-year-old woman with acute lymphoblastic leukemia was admitted to our hematology division to receive chemotherapy-based treatment for the disease. The patient's induction chemotherapy regimen was a daunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and l-asparaginase based Italian muliticenter protocol approved by the institutional review board of our university.

The patient was affected by chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, and she suddenly overnight developed fever (axillary temperature 38.5 °C) and abdominal pain and had two episodes of diarrhea. She complained of abdominal tenderness especially in the right upper and lower quadrants and in the epigastrium. The patient's vital signs were normal but the abdominal pain and fever did not resolve after intravenous paracetamol treatment. Two hours later, early in the morning, the patient's temperature was still 38.5 °C and the abdominal pain was worse particularly at the level of the right-side colon with exacerbation of pain upon palpation. Vital signs were still normal but the patient looked poor. Physical examination revealed abdominal distension with abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness. Transabdominal real-time US scanning of the bowel was performed using a 3.5–5 MHz convex probe and a 7 MHz linear transducer. Portable US equipment was used (Esaote model My Lab 25), and both axial and transverse scans were performed on the colon [5].

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of our university, and informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Results

At US scanning the colon wall appeared severely hypoechoic, non-stratified and thickened (11 mm) with loss of the haustral pattern. The lumen was distorted (not hyperechoic linear shaped) and there were highly echogenic lines running through the thickened wall that could be consistent with gas containing fissures [5]. The surrounding fat appeared homogenous and hyperechoic. Also the appendix (which was closely attached to the cecum) presented a thickened wall and was increased in size with fluid surrounding the viscera and with inflamed periappendicular fat. The colon appeared firm with no peristalsis, and the described pattern regarded only the cecum and ascending colon up to the proximal middle transverse colon. Small amounts of free periappendicular and perihepatic fluid were detected in the abdomen along the right paracolic gutter.

The rest of the colon (distal middle transverse, left colic flexure, descending colon and sigmoid colon) did not show any abnormal US features (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

US scanning: the colon wall looks severely hypoechoic non-stratified and thickened (11 mm) with loss of the haustral pattern. The lumen is distorted (white arrowheads). There are highly echogenic lines running through the thickened wall consistent with gas containing fissures (black arrowheads).

The patient had been afebrile until that morning and was being administered ciprolfoxacin and fluconazole prophylactic therapy as per the internal protocol for afebrile neutropenic patients.

Right after the transabdominal US examination, conservative medical management was started, such as bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, hydration and intravenous broad spectrum antibiotic treatment including appropriate anaerobic coverage and antifungal drugs. The patient's surveillance blood cultures were all negative (neutropenic afebrile patients undergo random surveillance blood culture tests twice a week as per the internal protocol of our institution). The patient was monitored for vital signs; she had normal blood pressure, moderate heartbeat and was breathing freely and well. Blood chemistry determined by portable blood analyser (STAT®) did not reveal impaired kidney or liver function, so dose adjustment of antibiotics was not required.

The patient's total white cell count was 290 × 109/L, hemoglobin level was 9.5 g/dL and platelet count was 45,000 × 109/L. The patient was severely neutropenic with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 20/μL.

Bedside transabdominal US findings and the patient's clinical status prompted us to call for urgent surgical consultation, alert the operating room, arrange for a volunteer granulocyte donor to be summoned to the blood transfusion center for a granulocyte donation and book platelet and fresh frozen plasma transfusion in view of a possible surgical intervention.

Surgical bedside examination confirmed the risk of colon rupture with consequent contamination of the peritoneal cavity and thus the necessity of surgical treatment and probable hemicolectomy.

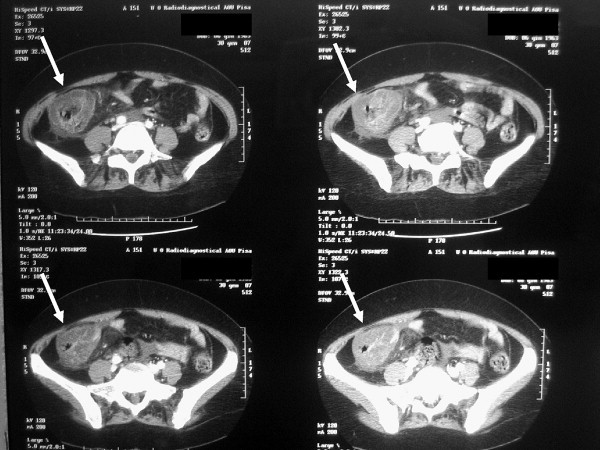

Before entering the operating room the patient underwent CT scan, which confirmed the US findings (Fig. 2) and she received the first doses of intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics with adequate anaerobic coverage and liposomal amphotericin-B. She also received the first granulocyte infusion, a prophylactic platelet transfusion and was started on subcutaneous administration of daily granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). Intravenous administration of morphine was necessary to control abdominal pain.

Fig. 2.

CT scan: view of the ascending colon with thickened wall and gas within the wall structure (with arrows).

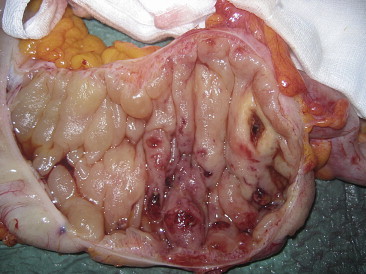

The patient underwent surgery about 4 h after the abrupt onset of severe abdominal symptoms and fever. Midline laparotomy was performed. Exploration of the abdominal cavity showed widespread serious effusion. Manual exploration of the viscera evidenced a greater thickness and congestion of the terminal ileum, cecum and ascending colon wall to the proximal transverse colon with perivisceral swelling and lymphadenopathy in the right end of the mesocolon. Right hemicolectomy was performed including resection of the right branch of the middle colic artery at its origin and regional lymphadenectomy, and in the end double-layer sutured side-to-side enterocolostomy was carried out (Fig. 3). Cultures from the surgical samples were negative.

Fig. 3.

Colon showing hemorrhagic necrosis, thickness and congestion of the wall.

The postoperative course was quite uneventful; the patient voided on the fourth day, and infection of two skin stitches was the only postsurgical negative consequence. Daily blood cultures were all negative.

The patient continued to receive intravenous antibiotic treatment, packed red blood cells and platelet transfusions, daily granulocyte transfusion and daily G-CSF.

Four days after hemicolectomy the patient fully recovered her white cell count. She was discharged from the surgical sub-intensive-care unit and retransferred to the Division of Hematology.

The patient was discharged with white cell count, hemoglobin level and platelet count within normal range. She was afebrile, and bone marrow assessment showed complete remission of the acute lymphoblastic leukemia by means of morphology, flow cytometry and molecular analysis. Abdominal US before discharge was normal.

The patient being clinically fully recovered and in complete remission of leukemia started a world wide search to identify a potential human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matched donor for a bone marrow transplant.

Discussion

NEC in cytopenic patients ranges from 2.6% [6] to 33% [7] with a pooled incidence rate of 5.3% related to 21 studies [8]. Despite aggressive management, mortality rates are high 21–48% [9]. NEC should always be suspected in neutropenic patients with abdominal pain, fever and diarrhea. Other specific diagnoses such as Clostridium difficilis induced pseudo-membranous colitis, ischemic colitis, acute appendicitis or intussusception should be excluded since the management of these pathologies is different. However, it may be impossible to make a differential diagnosis on the basis of clinical findings alone. The cecum is the predominant site of NEC probably due to its distensibility and limited blood supply (the term typhlitis was used in the early 1970s [10]). However, the small bowel (i.e. the terminal ileitis) and the colon (mainly the ascending portion) are sites of possible involvement.

Positive blood cultures (due to severe mucosal damage) have been found in 44% of patients in one series, and in up to 82% in others. The relatively low percentage in some series may be due to the use of prophylactic antibiotics in neutropenic patients.

Numerous microorganisms have been found in connection with NEC such as Clostridium septicum, Pseudomonas species, Enterococci, and Candida, and this knowledge guided our empirical treatment with intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics and antifungal drug. US was used to evaluate bowel-wall thickening (BWT). A thickness of >5 mm was considered abnormal, and the presence of gas within the colon wall, associated with the clinical picture of abdominal pain, fever and neutropenia were considered diagnostic of NEC. The degree of BWT was correlated with the outcome reported by Cartoni et al. that 60% of patients with BWT > 10 mm died from this complication compared with 4.2% of those with BWT ≤ 10 mm [11].

Early diagnosis is crucial to start conservative medical management which appears to be the best strategy in most cases. Some authors have proposed objective criteria for immediate surgical treatment such as: (1) persistent gastrointestinal bleeding in spite of resolution of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or clotting abnormalities; (2) free intraperitoneal perforation; and (3) clinical deterioration suggesting uncontrolled sepsis. Perforation of the colon wall occurs in 5–10% of cases. An accurate clinical evaluation of the patient by the Physician and Surgeon is mandatory in order to identify the cases which require surgery.

In our patient the abdominal symptoms and fever occurred abruptly, and a prompt bedside transabdominal US examination identified US features consistent with severe life-threatening NEC in a high risk neutropenic patient. Clinical symptoms and US findings suggested an urgent bedside surgical consultation which confirmed that surgical management was required, and before entering the operating room, the patient had already received the first dose of intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics with adequate anaerobic coverage, liposomal amphotericin-B and G-CSF. Furthermore, a volunteer granulocyte donor was called in for granulocyte donation.

Before surgery, CT scanning confirmed the presence of gas (as suggested by US) within the colon wall structure suggesting a high probability of perforation. This multidisciplinary procedure was carried out in a few hours. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial when dealing with this disease as there is no uniform approach to a successful management. A number of reports on NEC observed in patients with leukemia emphasize that early diagnosis of this disease was possible using US.

Transabdominal US proved to be a useful tool for identifying early signs of possible colon wall rupture and allowed an immediate real-time evaluation of the severity.

The mortality rate in patients with signs of perforation, sepsis and multi organ failure is higher than 50%. Had the colon wall rupture occurred, the likelihood of successful surgical intervention would have been poor in the presence of severe neutropenia.

A prompt bedside US scanning as soon as the symptoms developed was very useful and caused a multidisciplinary intervention and shift to surgical management. The timely intervention led to successful hemicolectomy in this severely neutropenic patient.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gomez L., Martino R., Rolston K.V. Neutropenic enterocolitis: spectrum of the disease and comparison of definite and possible cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:695–699. doi: 10.1086/514946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins G., Kushner J.P. Clostridial species in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis in patients with neutropenia. Am J Hematol. 1983;14:289–295. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830140311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbach D.R., Rostein O.D. Typhlitis. Can J Surg. 1999;42:415–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davila M.L. Neutropenic enterocolitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:44–47. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000198073.14169.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baud C., Saguintaah M., Veyrac C. Sonographic diagnosis of colitis in children. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:2105–2119. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mower W.J., Hawkins J.A., Nelson E.W. Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults with acute leukemia. Arch Surg. 1986;121:571–574. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400050089012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shamberger R.C., Weinstein H.J., Delorey M.J. The medical and surgical management of typhlitis in children with acute nonlymphocytic (myelogenous) leukemia. Cancer. 1986;57:603–609. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860201)57:3<603::aid-cncr2820570335>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorschluter M., Mey U., Strehl J. Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takaoka E., Kawai K., Ando S., Shimazui T., Akaza H. Neutropenic colitis during standard dose combination chemotherapy with nedaplatin and irinotecan for testicular cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:60–63. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietrich C.F., Hermann S., Klein S., Braden B. Sonographic signs of neutropenic enterocolitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Mar 7;12(9):1397–1402. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartoni C., Dragoni F., Micozzi A. Neutropenic enterocolitis in patients with acute leukemia: prognostic significance of bowel wall thickening detected by ultrasonography. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:756–761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]