Abstract

While occupational stress and fatigue have been well described throughout medicine, the radiology community is particularly susceptible due to declining reimbursements, heightened demands for service deliverables, and increasing exam volume and complexity. The resulting occupational stress can be variable in nature and dependent upon a number of intrinsic and extrinsic stressors. Intrinsic stressors largely account for inter-radiologist stress variability and relate to unique attributes of the radiologist such as personality, emotional state, education/training, and experience. Extrinsic stressors may account for intra-radiologist stress variability and include cumulative workload and task complexity. The creation of personalized stress profiles creates a mechanism for accounting for both inter- and intra-radiologist stress variability, which is essential in creating customizable stress intervention strategies. One viable option for real-time occupational stress measurement is voice stress analysis, which can be directly implemented through existing speech recognition technology and has been proven to be effective in stress measurement and analysis outside of medicine. This technology operates by detecting stress in the acoustic properties of speech through a number of different variables including duration, glottis source factors, pitch distribution, spectral structure, and intensity. The correlation of these speech derived stress measures with outcomes data can be used to determine the user-specific inflection point at which stress becomes detrimental to clinical performance.

Keywords: Stress, Voice analysis, Speech recognition

Introduction

Speech recognition technology is currently in widespread use for computerized medical report transcription. A number of operational, economic, and efficiency benefits are derived through the use of speech recognition including the digitization of medical data, elimination of third party transcription services, ability to archive data into a centralized database, and improved report turnaround and communication [1, 2]. Medical reports which previously required days for delivery can now be finalized and communicated in minutes, which improves the timeliness of health care delivery and in theory can lead to improved clinical outcomes [3]. Along with these derived benefits in operational efficiency and data management, adoption of speech recognition technology does come at a cost. By transferring editing and transcription responsibilities to the end user (i.e., radiologist), use of speech recognition can result in decreased productivity [4], which is of particular importance in the current practice environment of reduced economic reimbursements, increased data volume and complexity, and heightened expectations in service delivery [5]. These combined pressures have the potential to increase occupational stress and fatigue, which has been shown to be associated with increased errors, which is in turn can lead to adverse events and diminished health care outcomes [6–9].

A number of landmark publications have been issued from the Institute of Medicine which has highlighted the unexpectedly high frequency of medical errors and occupational stress/fatigue among health care professionals [7, 10]. Technology has been a double-edged sword for the radiology community. On one hand, it has dramatically improved the quality and accessibility of data, while on the other hand, it has created heightened expectations for health care consumers while precipitating stress associated with new technology adoption [11]. One solution to address these “technology-induced” stressors is to expand the intrinsic functionality of the technologies in use, so as to perform multiple applications in a single setting. In addition to the continued use of speech recognition technology for computerized report transcription, the same technology could simultaneously be used to measure and analyze occupational stress and fatigue in real-time, specific to the unique profile of each individual end user and context of the task being performed. The derived user-specific stress/fatigue analytics could be used in the creation of a number of workflow and quality-enhancing deliverables including customizable intervention strategies for stress/fatigue reduction, creation of automated workflow templates, and targeted quality assurance and peer review.

Occupational Stress and Fatigue in Radiology

Occupational stress and fatigue existing throughout medicine and radiology is no exception. Declining reimbursements, commoditization of services, disintegration of protective geographic boundaries, enlarging and more complex imaging datasets, and increasing demands for quality, safety, productivity, and timeliness all contribute to stress within the radiology community [5]. The resulting occupational stress and fatigue in radiology practice can manifest itself in a number of different forms including visual fatigue, decision fatigue, physiologic stress, and emotional stress [12]. To date, the one form of occupational fatigue which has been documented in radiology practice is visual fatigue, which has been shown to be increase with heightened work demands [13]. The combined forms of stress and fatigue can result in eye strain, faulty image perception, diagnostic uncertainty, inefficient workflow, and error (i.e., misinterpretation) [14, 15].

The resulting stress experienced in the workplace is dynamic in nature, affecting individuals to varying degrees, changing throughout the course of the workday, and modifying in accordance with task complexity and familiarity. As a result of this user and context variability in stress, measurement and analysis of occupational stress should be performed in real-time, with feedback provided at the point of care. The goal is to educate radiologists as to the presence and severity of stress/fatigue, while empowering them to proactively manage its effects through the creation of customizable intervention strategies, application of adaptable technology, and workload alteration. If properly channeled, the effects of occupational stress can be used to the advantage of the end user, but this first requires a thorough knowledge and understanding of its presence and impact on clinical performance.

Voice Stress Analysis

The intrinsic characteristics of speech can provide a number of insights about each individual human speaker, which collectively create unique “voice identification,” based upon their individual phonatory properties [16–18]. Human emotion, including psychological stress, can also be detected in speech through the use of voice stress analysis [19–21]. These factors are attributed to the fact that speech represents the output of a number of high level and integrated neurological systems including sensory, cognitive, and motor components [22].

The analysis of stress in speech can be performed using a voice stress analyzer (VSA), which operates by detecting stress in the acoustic properties of speech [23, 24]. A number of speech variables can be used in stress analysis including duration, glottal source factors, pitch distribution, spectral structure, and intensity [25–28]. While VSA focuses on the relatively narrow range of 8–14 Hz in speech, an alternative technology is layered voice analysis (LVA), which uses a wider spectrum for information extraction and can evaluate a wider range of emotions including excitement, confusion, and attention [29]. LVA is available in a wide variety of commercially available products including server-based intelligence systems, hand-held devices, and standard computer software. The derived analytics of VSA and/or LSA could be automatically generated through computational analysis and directly integrated into existing speech recognition technology displays, in accordance with individual end user viewing preferences. The education and training for VSA/LSA display and analysis could be performed in conjunction with that of speech recognition, so end users would concurrently learn implementation strategies for both technologies in tandem.

Both intrinsic and extrinsic stressors have been reported to affect acoustic speech. Extrinsic stressors are often environmental in nature, while intrinsic stressors can take a number of forms including high workload stress, multi-tasking, emotional state, and occupational fatigue [30]. These intrinsic stressors are the primary focus of the proposed technology, and whose presence ironically has been shown to impact speech recognition performance [31–34]. As a result, knowledge and understanding of stress in speech can simultaneously serve as a means for improving both clinical and technical performance of radiologist end users.

The objective measurement and characterization of intrinsic stress in speech has been applied to date in a number of occupational settings including aviation, law enforcement, military, and telecommunications [29, 35, 36]. Examples of “stressed speech classification” include categorizing and prioritizing emergency 911 call services, assessment of pilot fatigue, analysis of battlefield stress, and assessment of emotional state among crime suspects. In many respects, pilots and radiologists share many similarities relating to time urgency, decision fatigue related to cognitive overload, and technology dependence in job performance. As a result, the application of stress speech analysis in radiology may provide a similar role to that already used for pilots. The key to success in radiology practice will be largely predicated on the ability to characterize subtle stress-related changes in speech in a context and user-specific fashion, through the creation of personalized speech profiles.

The Personalized Speech Profile

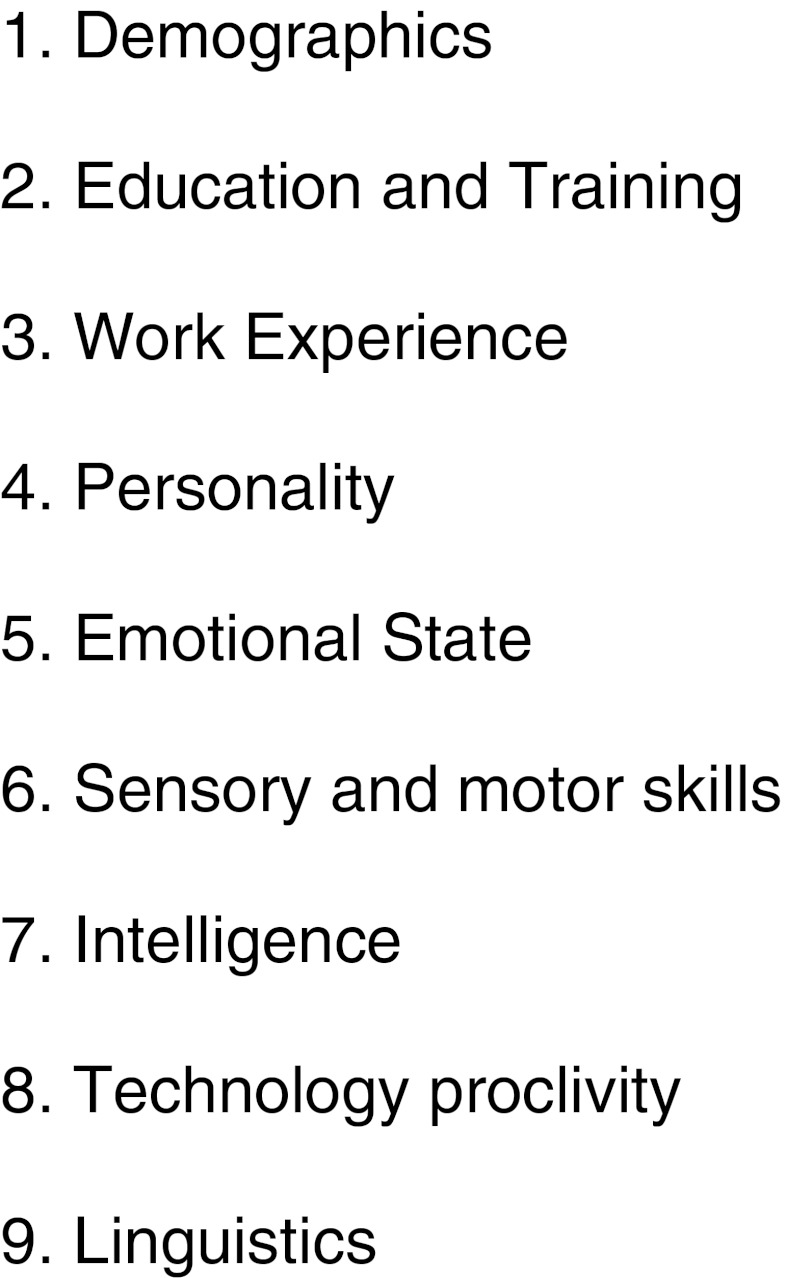

The ability to create a personalized speech profile is directly related to the uniqueness of each individual end user’s speech characteristics. In addition to speech-related characteristics, the personalized speech profile takes into account a number of other user-specific factors which have the potential to affect occupational stress and fatigue (Fig. 1) [37]. These individual profile attributes reflect how the population of practicing radiologists (and other health care professionals) is unique to one another and do not represent a homogeneous population, which is not reflected in conventional technology development and implementation [38].

Fig. 1.

Variables used for end user speech stress profiling

Due to the fact that work demands and stress/fatigue measures are constantly changing, the personalized speech profile is designed to be dynamic in nature and respond to this stress variability. Some stressors are relatively predictable (e.g., cumulative workload, increasing task complexity) and can therefore be incorporated into routine workflow. Other stressors are far more variable and less predictable (e.g., emotional state) and require an adaptive method for measurement and intervention. It is therefore important that the personalized speech profile take into account these changing stressors and correlate them with the historical performance and stress measures of the individual end user. The dynamic nature of this data collection and analysis provides an iterative mechanism for technology refinement, with the goal of continuously improving the accuracy and predictability of stress analysis in speech along with the interaction effects of various stressors.

The uniqueness of each personalized speech profile provides an additional application of the technology, as a dynamic method for end user identification and authentication. The profile could be employed to validate each individual end user’s identity, in a manner similar to biometrics technologies. Unlike conventional biometrics technologies which are static and fixed (e.g., fingerprint or retinal scanning), the speech profile would provide a method for dynamic user identification and authentication. Not only could an end user’s identity be validated with the technology, but the corresponding stress measure recorded during the authentication process could be cross-referenced with the individual end user’s speech stress profile database to gauge how this stress relates to the historical measures of the end user and resulting performance outcomes. The result of this analysis could determine the degree of access and workflow allowed, in keeping with the specific task being performed. As an example, an interventional radiologist preparing to perform a technically challenging procedure may be required to undergo identification and authentication using speech stress analysis. The input data would be used to collectively validate their identity, correlate the stress measurement with their personalized profile, and correlate this with context-specific performance data. In one example, the interventional radiologist’s recorded stress measurement may be within a range consistent with high performance and safety measures for the specific procedure and authentication would be granted. In another example, the interventional radiologist’s recorded stress measure may be associated with lower than acceptable quality/safety performance data. In this scenario, a preemptory alert may notify the radiologist of the concern and trigger an alternative strategy (e.g., postponing the procedure, deferring to another colleague).

The dynamic capabilities of the personalized speech profile can also extend to stressors affecting speech (e.g., sleepiness, illness), which could impact stress and job performance. The ability to longitudinally track and analyze speech characteristics over a prolonged time period of use for each individual end user provides a mechanism for determining the degree of speech variability and its relationship to external stressors. The ultimate goal is to continuously refine the personalized speech profile in accordance with the dynamic and changing attributes of each individual end user, while using historical stress and performance data to predict future stress and guide “best use” applications of the technology, as it relates to the specific task and end user.

Implementation Goals and Objectives

The combined standardized speech stress analysis, personalized profile, task complexity, and clinical outcomes data could ultimately be used to determine the specific inflection point at which performance metrics begin to deteriorate with elevated stress levels, which would be specific to both the individual end user and tasks being performed. In order to take into account the dynamic nature of these data, it is essential that longitudinal user and context-specific stress data be utilized, in order to account for fluctuations in performance. The calculated levels of “acceptable stress” will be unique to each individual end user and can change over time, in accordance with their individual performance and stress data variations. This adaptability of the data and technology implementation strategy is predicated on the simple facts that individual end users experience stress differently and exhibit different performance outcomes, which are often task dependent. Societal standards based upon meta-analysis of the data can determine the quality threshold requirements, and these can in turn be applied to each individual end user to determine the inflection point for triggering intervention.

The various types of intervention strategies have been described [8] and can include changes to workload distribution, employment of automated workflow templates, use of computerized decision support tools, and mandatory time-outs (with personalized stress reduction options). The goal is to ensure quality standards are maintained in keeping with the unique performance data of each individual end user, while also providing some degree of flexibility in accordance with individual end user preferences and workflow demands.

The derived analytics could be used to create a number of functional tools, which could be adapted to institutional and individual end user requirements and expectations. These could include the following:

Real-time measurement of occupational stress and fatigue in speech.

Creation of a standardized stress database, which can be correlated with workflow and outcomes data.

Creation of an end user profiling system which can take into account the unique attributes of each individual end user and the various stressors (both internal and external) experienced.

Creation of customizable stress interventions commensurate with individual end user preferences, profile characteristics, and performance.

Technology assessment tool, which provides a standardized mechanism for correlating stress/fatigue measures with workflow, task complexity, and clinical outcomes.

The implementation of the proposed technology could potentially have an adverse effect on radiologist productivity and departmental workflow, as voluntary and/or involuntary “time-outs” are taken to respond to increasing stress levels. While larger imaging departments could more easily accommodate to these productivity and workflow changes, smaller imaging departments with less personnel could be adversely affected. Strategies to address these potential changes in workflow/productivity could include schedule modification (e.g., scheduling interventional procedures earlier when occupational stress/fatigue levels are lowest) and selective outsourcing of diagnostic imaging studies (e.g., through teleradiology) during high stress/high volume periods. Another concern for technology implementation is the potential for heightened medicolegal scrutiny. The goal of the technology is to provide end users with personalized stress and outcomes performance data, with the hopes of improving quality outcomes. If used as designed, this could ultimately provide objective data to justify practice patterns and serve as a defense in the case of an adverse clinical outcome. The goal is to optimally balance the often competing demands of enhanced quality and productivity.

Conclusion

While speech recognition technology has provided significant improvement in operational efficiency in radiology practice, its intrinsic functionality is currently underutilized and largely limited to computerized report transcription. Speech offers a number of additional applications including stress analysis, which has been successfully used in a number of nonmedical applications. The integration of voice stress analysis in radiology practice could be readily facilitated through existing speech recognition technology and could provide an objective mechanism for quantifying occupational stress in real time, while also providing valuable insights as to how stress impacts workflow and quality performance on both individual and collective perspectives. Since occupational stress is both user and context-specific, implantation of voice stress analysis should take into account the unique attributes of individual end users as well as the diversity and complexity of tasks being performed. This inter- and intra-radiologist stress variability can be accounted for by the creation of personalized speech stress profiles, which provide insights as to how unique individual attributes affect stress and how this data can be used to create customized stress intervention strategies. While the primary goal of implementing speech stress analysis into everyday clinical practice is improved quality, other derived benefits could include improved job satisfaction, workflow/productivity, and emotional well-being.

References

- 1.Halsted MJ, Froehlee M. Design, implementation, and assessment of a radiology workflow management system. AJR. 2008;191:321–327. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White KS. Speech recognition implementation in radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:841–846. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-1511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koivikko MP, Kauppinen T, Ahovuo J. Improvement of report workflow and productivity using speech recognition—a follow up study. J Digit Imaging. 2008;21:378–382. doi: 10.1007/s10278-008-9121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiner BI, Siegel EL, Knight N. Radiology reporting: past, present, and future: the radiologist perspective. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;5:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiner B, Kruspinski EA. The insidious problem of fatigue in medical imaging practice. J Digit Imaging. 2012;1:3–6. doi: 10.1007/s10278-011-9436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leape LL. Errors in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851–1857. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520230061039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington DC: National Academy; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiner B, Kruspinski EA. Innovation strategies for combating occupational stress and fatigue in medical imaging. J Digit Imaging. 2012;25:445–448. doi: 10.1007/s10278-011-9437-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmreich RL. On error management: lessons from aviation. BMJ. 2000;32:781–785. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crossing the Quality Chasm: a New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiner BI, Siegel EL, Siddiqui K. Evolution of the digital revolution: a radiologist perspective. J Digit Imaging. 2003;16:324–330. doi: 10.1007/s10278-003-1743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krupinski EA, Reiner B. Real-time occupational stress and fatigue measurement in medical imaging practice. J Digit Imaging. 2012;25:319–324. doi: 10.1007/s10278-011-9439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vertinsky T, Forster B. Prevalence of eye strain among radiologists: influence of viewing variables on symptoms. AJR. 2005;184:681–686. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krupinski EA. Medical image perception issues for PACS deployment. Semin Roentgenol. 2003;38:231–243. doi: 10.1016/S0037-198X(03)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krupinski EA, Berbaum KS, Caldwell RT, et al. Long radiology workdays reduce detection and accommodation accuracy. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollien H, Scwartz R. Speaker identification utilizing noncontemporary speech. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2001;46:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuenzel H. On the problem of speaker identification by victims and witnesses. Forensic Linguistics. 1994;1:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens KN: Sources of inter and intra-speaker variability in the acoustic properties of speech sounds. Proceedings of the 7th International Cons. Phonetics Sciences, Montreal, 1971, pp 206–232

- 19.Cummings K, Clements M. Analysis of global waveforms across stress styles. Proceedings of the IEEE, ICASSP. 1990;2847:369–372. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollien H, Saletto JA, Miller SK. Psychological stress in voice: a new approach. Sturdia Phonetica Posnaniensa. 1993;4:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams CE, Stevens KN. Emotions and speech: some acoustical correlates. Journal of the Associated Society of America. 1972;2:1238–1250. doi: 10.1121/1.1913238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.http://www.voicestress.org/voicestress (Florida Study). Pdf

- 23.Brockway BF, Plummer OB, Lowe BM. The effects of two types of nursing reassurance upon patient vocal stress levels as measured by a new tool, the PSE. Nurs Res. 1976;25:440–446. doi: 10.1097/00006199-197611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Car DH, Greaner J, Hibler N, et al. A description and analysis of the operation and validity of the psychological stress evaluator. J Forensic Sci. 1980;25:174–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams CE, Stevens KN. Emotions and speech: some acoustic correlates. J Acoustic Soc Am. 1972;52:1238–1250. doi: 10.1121/1.1913238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streeter LA, Macdonald NH, Apple W, et al. Acoustic and perceptual indicators of emotional stress. J Acoustic Soc Am. 1983;73:1354–1360. doi: 10.1121/1.389239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rostolland D. Acoustic features of shouted voice part 1. Acustica. 1982;50:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieberman P, Michaels S. Some aspects of fundamental frequency and envelope amplitude as related to the emotional content of speech. J Acoustic Soc Am. 1962;7:922–927. doi: 10.1121/1.1918222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopkins CS, Ratley RJ, Benincasa DS, et al: Evaluation of voice stress analysis technology. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2005, pp 1–10

- 30.Zhou G, Hansen JHL, Kaiser JF. Nonlinear feature based classification of speech under stress. IEEE Transactions on Speech and Audio Processing. 2001;9:201–216. doi: 10.1109/89.905995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baber C, Mellor B, Graham R, et al. Workload and the use of automated speech recognition: the effects of time and resource demands. Speech Commun. 1996;20:37–54. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(96)00043-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y. Cepstral domain talker stress compensation for robust speech recognition. IEEE Trans Acoust, Speech, Signal Processing. 1988;36:433–439. doi: 10.1109/29.1547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray IR, Baber C, South A. Toward a definition and working model of stress and its effects on speech. Speech Commun. 1996;20:3–12. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(96)00040-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitmore J, Fisher S. Speech during sustained operations. Speech Commun. 1996;20:55–70. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(96)00044-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuroda I, Fujiwara O, Okamura N, et al. Method for determining pilot stress through analysis of voice communication. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 1976;47:528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson TR, Moore TJ, McKinley RL: Issues in the development and use of speech recognition database for military cockpit environments. Proc of Speech Tech’85, Media Dimensions, 1985, pp. 172–176

- 37.Reiner B, Kruspinski EA. Demystifying occupational stress and fatigue through the creation of an adaptive end-user profiling system. J Digit Imaging. 2012;2:201–205. doi: 10.1007/s10278-011-9441-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiner B. One size (doesn’t) fit all. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;4:567–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]