Abstract

In mammals, postnatal haematopoiesis occurs in the bone marrow (BM) and involves specialized microenvironments controlling haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) behaviour and, in particular, stem cell dormancy and self-renewal. While these processes have been linked to a number of different stromal cell types and signalling pathways, it is currently unclear whether BM has a homogenous architecture devoid of structural and functional partitions. Here, we show with genetic labelling techniques, high-resolution imaging and functional experiments in mice that the periphery of the adult BM cavity harbours previously unrecognized compartments with distinct properties. These units, which we have termed hemospheres, were composed of endothelial, haematopoietic and mesenchymal cells, were enriched in CD150+ CD48− putative HSCs, and enabled rapid haematopoietic cell proliferation and clonal expansion. Inducible gene targeting of the receptor tyrosine kinase VEGFR2 in endothelial cells disrupted hemospheres and, concomitantly, reduced the number of CD150+ CD48− cells. Our results identify a previously unrecognized, vessel-associated BM compartment with a specific localization and properties distinct from the marrow cavity.

Keywords: bone marrow, endothelium, haematopoiesis, perivascular cells

Introduction

The mammalian skeletal system contains a specialized network of highly branched, sinusoidal blood vessels, which play important roles in the regulation of the surrounding tissue and have been functionally linked to processes as diverse as bone formation and haematopoiesis (Yin and Li, 2006; Bianco, 2011; Doan and Chute, 2012). Tissue-derived VEGF family growth factors and their endothelial receptors—most importantly, the ligand-receptor pair VEGF-A and VEGFR2/Flk1—are key regulators of angiogenic blood vessel growth both under physiological and pathological conditions (Olsson et al, 2006; Carmeliet and Jain, 2011). In bone development, mesenchymal cells and growth plate chondrocytes are major sites of VEGF-A production, which attracts growing vessels and stimulates the expansion of the local vasculature (Zelzer and Olsen, 2005; Wang et al, 2007; Eshkar-Oren et al, 2009). VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signalling in healthy, adult mice is also required for the maintenance of vessel beds in organs such as endocrine glands, intestine, lung and kidney, which, like sinusoidal vessels in the bone, all carry fenestrations (Kamba et al, 2006). Highlighting that sinusoidal vessels, osteogenesis and the haematopoietic system are coupled, excessive VEGF production not only enhanced the ossification of bones, but also led to haematological changes (Wang et al, 2007; Maes et al, 2010). Among other cell types, sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) and perivascular mesenchymal (stem and osteoprogenitor) cells have been shown to control haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) behaviour. CXCL12-abundant reticular cells, which are found in endosteum as well as in close association with SECs in the marrow cavity, are required for the maintenance of the HSC pool (Sugiyama et al, 2006). Likewise, CD146-positive osteoprogenitors, the mesenchymal precursors that give rise to osteoblasts, together with SECs can organize an ecotopic haematopoietic niche after xenotranplantation (Sacchetti et al, 2007). Nestin-expressing mesenchymal stem cells have been proposed to form a niche with HSCs that is influenced by the surrounding microenvironment and hormonal signals (Mendez-Ferrer et al, 2010). However, it was recently shown that most HSCs were lost when the gene encoding murine stem cell factor was simultaneously inactivated in SECs and leptin receptor-expressing perivascular cells, whereas the targeting of Nestin+ cells did not affect HSC frequency and function (Ding et al, 2012). Further arguing for a central role of SECs in the haematopoietic system, the expression of VEGFR2 was required for the engraftment of transplanted haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells into irradiated recipient mice (Hooper et al, 2009).

Regardless of these important insights into the role of specific stromal cells and molecular signals regulating haematopoiesis, relatively little is known about the distribution and organization of key cell types and specific microenvironments in the bone marrow (BM) cavity. Previous studies have suggested that the abundance and proliferation of colony-forming cells in the murine femur increase towards the inner surface of the bone (Lord et al, 1975; Frassoni et al, 1982). Colony-forming units were also found in multicellular aggregates, termed as ‘hematons’, found in BM aspirates (Blazsek et al, 1995). Despite these findings, insight into the structural or functional compartmentalization of the marrow in situ remains very limited. Here, we report the existence of a previously unrecognized BM compartment composed of endothelial, mesenchymal and haematopoietic cells. These structures, which we have termed hemospheres, have a distinct morphology and other features distinguishing them from the marrow cavity. Utilizing the lineage hierarchy and clonal growth properties of haematopoietic cells (Becker et al, 1963; Dick et al, 1985), we have used advanced genetic labelling to show that hemospheres are previously unrecognized, VEGFR2-dependent sites of clonal haematopoietic cell expansion in the adult organism.

Results

SEC subpopulations in the BM

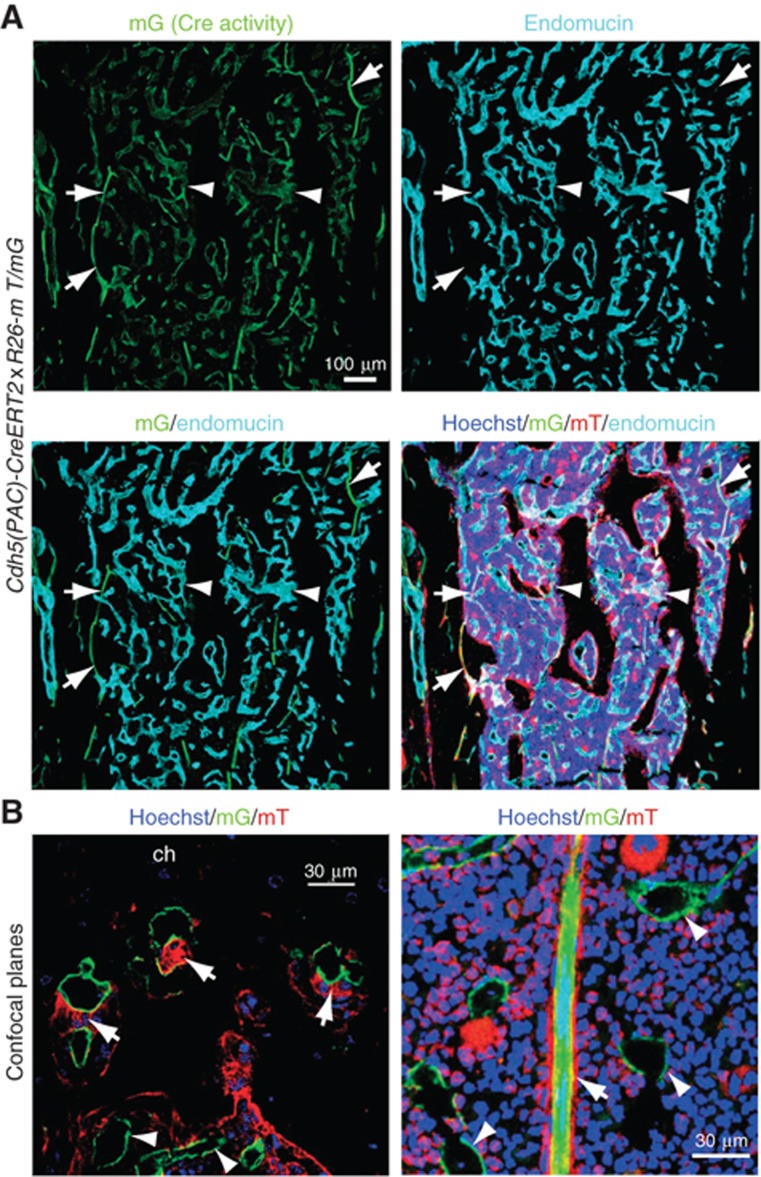

Since numerous studies had indicated important roles of SECs in the adult BM, we investigated the organization of BM vessels in the context of the surrounding tissue by combining endothelial-specific, tamoxifen-inducible Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 transgenics (Wang et al, 2010) with mT/mG Cre reporter mice (Muzumdar et al, 2007). While the resulting offspring displayed ubiquitous expression of membrane-targeted tomato protein (mT), administration of tamoxifen and activation of Cre recombinase led to the excision of the mT cassette and expression of membrane-attached enhanced green fluorescent protein (mG) with a very high efficiency in endothelial cells (Figure 1A and B). This method permitted the detailed analysis of the sinusoidal endothelium and the surrounding tissue without the technical drawbacks related to specificity and penetration of antibodies in thick tissue sections. A previous study has reported two different endothelial structures in the BM of long bone, namely VEGFR3− VEGFR1+ arterioles and VEGFR2+ VEGFR3+ SECs (Hooper et al, 2009). Those two vessel types can be readily distinguished with antibodies recognizing endomucin (Morgan et al, 1999), which labelled all SECs but not arterioles and arteries (Figure 1A). Furthermore, we found that sinusoidal vessels can be further classified into two subtypes that are either associated with or devoid of perivascular, tomato-positive (non-endothelial) cells (Figure 1B and 2A). While the majority of vessels in the BM lacked perivascular cells, mT+ cell coverage was seen on those at the periphery of the BM cavity close to the growth plate chondrocytes of the metaphysis, a structure that persists in adult rodents (Figure 1B). These vessels had a diameter of 10–25 μm and, upon ultrastructural examination, were associated with cells that were morphologically identified as bone-resorbing osteoclasts or as cells with a mesenchymal morphology (Supplementary Figure 1A). Antibody staining indicated that the latter corresponded to cells expressing markers that are characteristic of pericytes and mesenchymal osteoprogenitors such as NG2, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ), Nestin and CD146 (Armulik et al, 2005; Crisan et al, 2008; Mendez-Ferrer et al, 2010) (Supplementary Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Gene targeting in the BM vasculature. (A) Maximum intensity projection of confocal images showing sinusoidal vessels in the femoral bone marrow cavity of a 3-month-old Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 x ROSA26-mT/mG mouse. Cre-induced mG signal marks endomucin-negative arterioles (arrows) as well as virtually all endomucin+ sinusoidal capillaries (arrowheads). (B) Confocal planes showing the association of mT+ perivascular cells (arrows in left image, red) with vessels in direct proximity of the growth plate (left) but not in the sinusoidal vasculature (arrowheads) within the marrow cavity of 3-month-old Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 x ROSA26-mT/mG mice. Image on the left shows an individual confocal plane of the inset in Figure 2A. Arrow in right image indicates an arteriole. SECs (green) and cell nuclei (Hoechst, blue) are labelled. Ch, chondrocytes.

Figure 2.

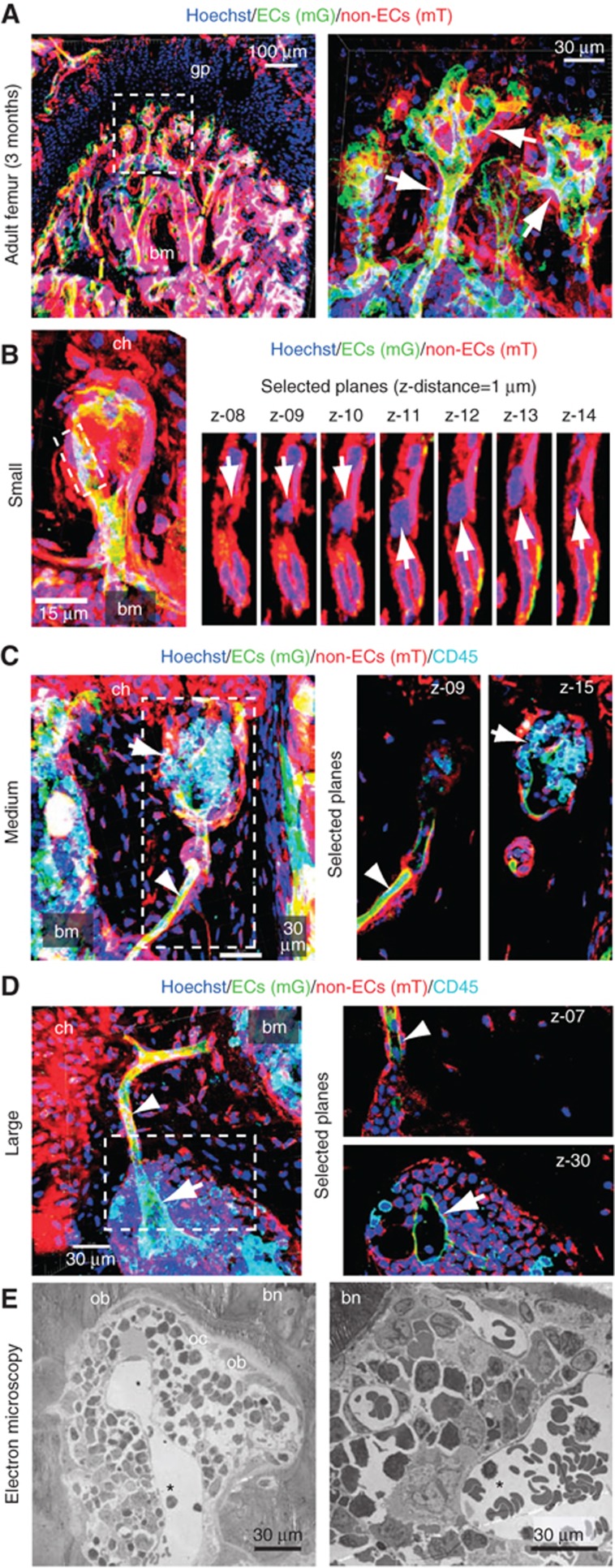

Morphological features of hemospheres. (A) Maximum intensity projection of the metaphyseal region near the growth plate (gp) in a 3-month-old Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 × ROSA26-mT/mG mouse. ECs (mG, green), non-endothelial cells (mT, red) and cell nuclei (blue) are labelled. Right panel, inset at higher magnification. Vessels covered by mT+ cells (arrows) and trabecular bone marrow (bm) are indicated. (B–D) Visualization of hemospheres in mT/mG mice. Individual confocal planes (right) and projection of Z-stack (left) are shown. Chondrocytes (ch) and bone marrow (bm) are indicated. (B) Smallest structures show the separation of the mG+ endothelial and mT+ perivascular layers (elongated nuclei) with enclosed putative haematopoietic cell (round nucleus, arrow). (C), More CD45+ (cyan) haematopoietic cells were found in the enlarged space between ECs and mT+ cells in bigger hemospheres (arrow), while mG+ and mT+ cells remained associated in the vessel outside this structure (arrowhead). The central capillary (arrow) was dilated in large hemospheres in comparison to the adjacent vessel (arrowhead). (D) In the largest hemospheres, the number of enclosed CD45+ cells was increased further. (E) Electron micrographs of hemospheres with central lumenized endothelium (asterisk), surrounding haematopoietic cells, peripheral osteoblasts (ob) and osteoclasts (oc), and enclosing bone (bn).

Identification of a peripheral, vessel-associated BM compartment

The vascular structures at the BM periphery showed further heterogeneity. In a small fraction (<5%) of distal vessels, we observed the detachment of the outer, mT+ layer from the endothelium and the appearance of additional cells with round nuclei in the resulting space (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 2). In larger (30–90 μm in diameter) structures of this type, the area between ECs and perivascular cells was further expanded and, concomitantly, the number of the enclosed cells, which expressed the marker CD45, increased (Figure 2C; Supplementary Figure 2). As these bulged, cyst-like and often spherical haematopoietic cell-containing units have not been described previously, we termed them as hemospheres. In hemospheres exceeding an outer diameter of about 150 μm, the central vessel had a diameter of 60–120 μm (Figure 2D; Supplementary Figure 2). Ultrastructural analysis also showed that the endothelium inside these large units was indeed no longer associated with mesenchymal cells or osteoclasts, but rather represented regular sinusoidal capillaries that were surrounded by haematopoietic cells on their outer (abluminal) surface (Figure 2E; Supplementary Figure 6B–E). The mT+ cells in the outer lining of hemospheres expressed the osteoblast lineage markers Runx2, osterix, osteopontin and N-cadherin (Supplementary Figure 3). This pattern of marker expression suggests the differentiation of perivascular mesenchymal cells, which have a known lineage relationship with osteoblasts and can function as osteoprogenitors (Maes et al, 2007; Valtieri and Sorrentino, 2008), during the formation of hemospheres.

Structures bearing all key features of hemospheres were also observed in the sternum, in the epiphyseal cartilage of secondary ossification centres, in vertebrae, in the skull as well as in human femur (Supplementary Figure 4). This suggests that hemospheres reflect a common structural compartment shared by different BM-containing skeletal elements and mammalian species.

Enrichment of CD150+ CD48− haematopoietic cells in hemospheres

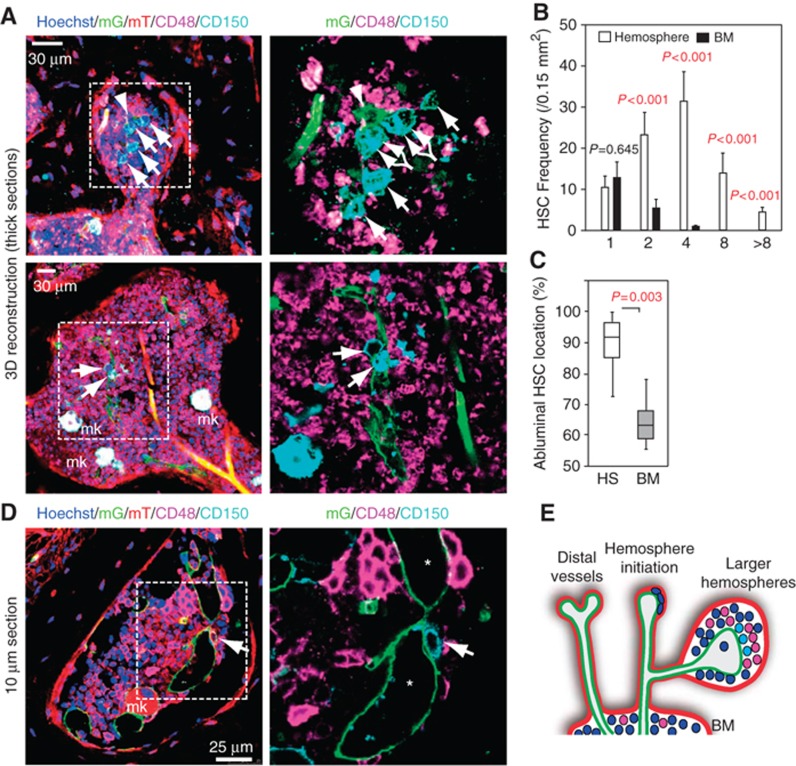

Since CD45+ haematopoietic cells were abundant in hemospheres, we further investigated the cellular composition of this compartment. According to the SLAM code established by Morrison and colleagues (Kiel et al, 2005), the CD150/SLAMF1+ CD48/SLAMF2− cell population is strongly enriched for HSCs. While the staining and imaging of hemospheres in thin tissue sections from Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mT/mG mice revealed the presence of single CD150+ CD48− cells, 3D reconstruction of thick tissue sections (see Materials and methods) permitted the visualization of multiple CD150+ CD48− cells in small clusters (Figure 3A–D; Supplementary Figure 5). Notably, clusters composed of more than two CD150+ CD48− cells were exclusively found inside hemospheres, but not in the BM cavity (Figure 3B), and were typically associated with the abluminal surface of sinusoidal vessels (Figure 3A, C and D), which is similar to what has been previously reported for single CD150+ CD48− cells in the BM cavity (Kiel et al, 2005). We also confirmed that CD150+ CD48− cells did not express lineage markers (Supplementary Figure 6A) and might therefore, in accordance with the SLAM code, potentially represent HSCs. Megakaryocytes and their progenitors, which are also CD150+ CD48−, were readily distinguishable because of their large size and nuclei (Figure 3A and D; Supplementary Figure 6A). Ultrastructural examination of hemospheres confirmed that vessel-associated haematopoietic cells displayed characteristic features of stem and progenitor cells, such as the low abundance of cellular organelles, globular shape and lack of inner membranes in mitochondria (Zeuschner et al, 2010; Supplementary Figure 6B–E).

Figure 3.

Enrichment of CD150+ CD48− cells in hemospheres. (A) 3D reconstruction of hemospheres in thick (100 μm) sections from a 6-week-old Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 x ROSA26-mT/mG femur. All channels (left) or only mG+ SECs (green, arrowhead in top panels) together with CD150 (cyan) and CD48 (magenta) immunofluorescence (right) are shown. CD150+ CD48− putative HSCs (arrows) and megakaryocytes (mk) are indicated. (B) Frequency of CD150+ CD48− cells (number per area) in hemospheres containing a total of 1, 2, 4, 8 or more of such cells, as indicated. Note that the CD150+ CD48− population was most concentrated in smaller hemospheres containing 2–4 of such cells. Equivalently sized areas (black bars) in the BM cavity hold only 1 or, in rare cases, 2 CD150+ CD48− cells. Error bars, s.e.m. (C) CD150+ CD48− cells inside hemospheres (HS) were predominantly associated with the abluminal surface of vessels. BM, bone marrow. Error bars, s.e.m. (D) Confocal section showing presence of CD150+ CD48− cells on the abluminal surface of a sinusoidal vessel inside hemosphere (lumen marked by asterisks). Mk, megakaryocyte. Right panel, higher magnification of inset. (E) Proposed model for the initiation and organization of hemospheres around distal sinusoidal vessels. SEC (green), perivascular mesenchymal cells (red), CD150+ CD48− cells (light blue) and other haematopoietic cells (purple and dark blue) are indicated.

Taken together, the evidence above suggests that hemospheres might be a specialized BM compartment, which is formed around distal, mesenchymal cell-covered vessels and contains CD150+ CD48− cells in high abundance (Figure 3E).

Distinct properties of hemospheres

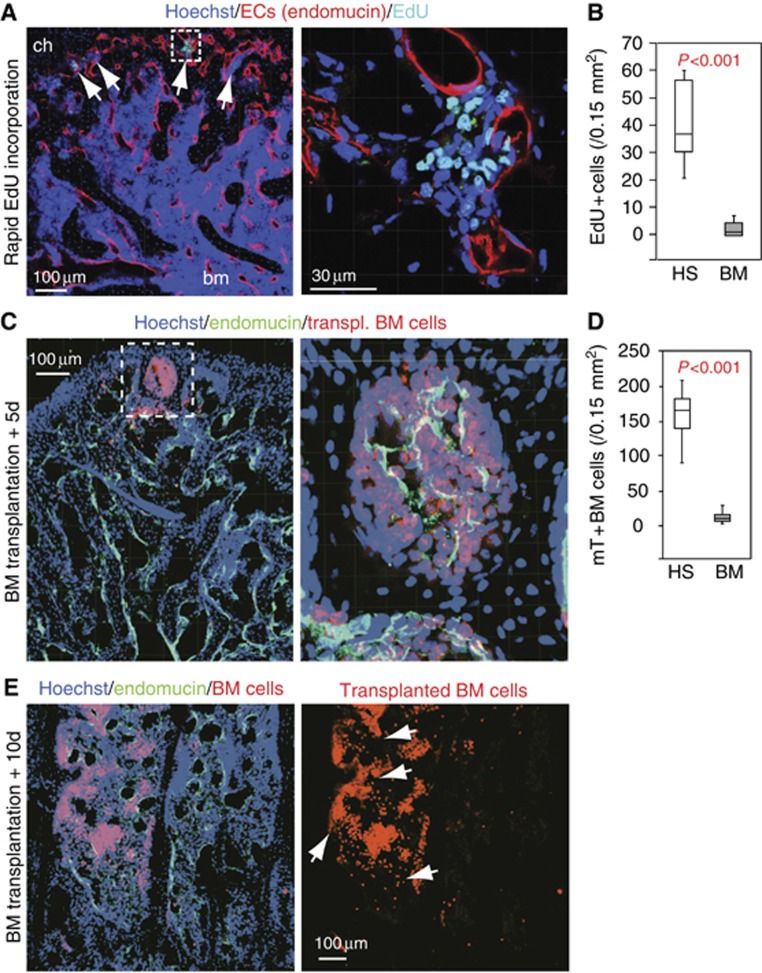

Besides the concentration of CD150+ CD48− cells, several other specific features distinguished hemospheres from the adjacent BM cavity. Indicating rapid haematopoietic cell proliferation within hemospheres, short-term EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) labelling of mitotic cells (see Materials and methods) robustly marked cell clusters in hemospheres, while significantly fewer labelled cells were seen in the BM cavity under the same conditions (Figure 4A and B). EdU+ cells displayed the round nuclear morphology of haematopoietic cells (Figure 4A) and were found in the same regions as CD45+ cells. SECs and cells of the osteogenic lineage were not labelled by this approach. We further confirmed that almost all EdU+ cells were not immunostained by antibodies recognizing lineage markers (Supplementary Figure 7A). In contrast, a fraction of around 30% of the EdU-labelled population exhibited CD48+ immunostaining (Supplementary Figure 7B), suggesting that these cells might potentially represent transit amplifying progenitors (Kiel et al, 2005).

Figure 4.

Distinct properties of hemospheres. (A) Rapid EdU incorporation in haematopoietic cells in hemospheres (arrows) at the periphery of the bone marrow. Cells in the BM cavity (bm) are not labelled under the same conditions. Right, higher magnification of inset in left panel. (B) Quantitation of cells labelled by rapid EdU incorporation inside hemospheres (HS) or bone marrow (BM). Error bars, s.e.m. (C) Intrafemorally injected, mT+ haematopoietic cells (red) are found preferentially in hemospheres in proximity of SECs at day 5 (+5d) after transplantation (endomucin, green). Right image is higher magnification of inset. Nuclei, Hoechst (blue). (D) Distribution of transplanted BM cells at 5 days after transplantation in HS in comparison to BM. Error bars, s.e.m. (E) Intrafemorally injected haematopoietic cells (red) colonize the bone marrow cavity (arrows) at 10 days (+10d) after transplantation. Right image shows red fluorescence only. Nuclei, Hoechst (blue); SECs, endomucin (green).

Following lethal irradiation and intrafemoral injection of fluorescently labelled BM cells, clusters of transplanted cells were found inside hemospheres at the periphery of the BM after 5 days. At this time point, very few fluorescent BM cells were found in the marrow cavity (Figure 4C and D), which was only populated by labelled cells by day 10 after transplantation (Figure 4E). Thus, repopulation of irradiated BM by transplanted haematopoietic cells was first seen in hemospheres and extended later to the rest of the BM cavity.

Lineage tracing of haematopoietic cells in the BM

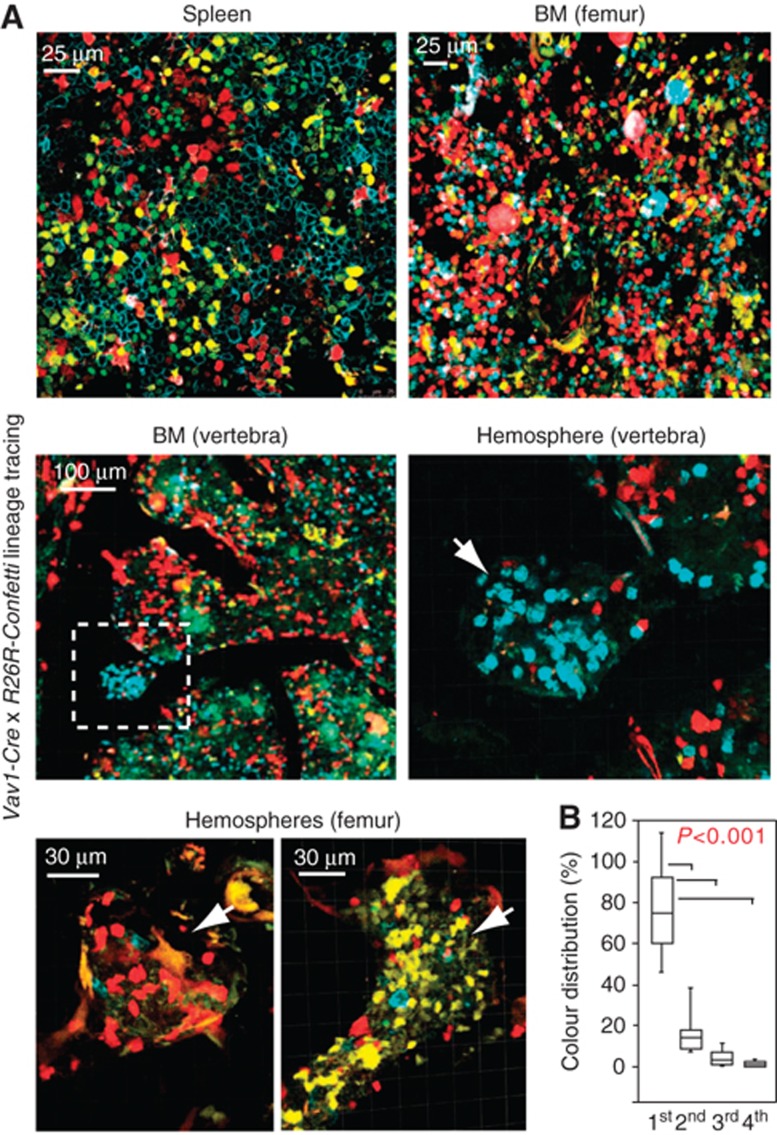

Genetic fate mapping has emerged as a powerful tool for the investigation of lineage relationships and clonal expansion processes (Snippert et al, 2010; Rinkevich et al, 2011). To address whether hemospheres were gradually filled by cells coming from the BM cavity or rather by local, clonal haematopoietic cell growth, we combined Vav1-Cre transgenics (de Boer et al, 2003) with R26R-Confetti mice. The latter are Cre reporters, which can express four different fluorescent proteins in a stochastic fashion in Cre-expressing cells (Snippert et al, 2010). The resulting double transgenic animals showed robust Cre reporter activity in the spleen and the BM cavity of all skeletal elements (Figure 5A). In the latter, differently coloured haematopoietic cells showed a random, highly mixed distribution (Figure 5A). Closer examination of hemospheres in femur and vertebra revealed that they preferentially contained cells labelled with a single fluorescent colour, while the same did not apply to the directly adjacent BM cavity (Figure 5A and B). Local expansion of uniformly coloured transplanted haematopoietic cells was also observed in the long bone of lethally irradiated recipient mice (Supplementary Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Clonal haematopoietic cell expansion in hemospheres. (A) Genetic lineage tracing with Vav1-Cre and R26R-Confetti transgenics in spleen and BM of 2-week-old mice (top panels), and in 6-week-old vertebrae (centre) or femur (bottom). Indicating clonal expansion, cell clusters of one colour are dominant in hemospheres. Centre right image is higher magnification of inset on the left. (B) Dominance of uniformly coloured cells (1st) inside hemospheres compared to the other, less prevalent colours (2nd, 3rd, 4th). Error bars, s.e.m.

As it is statistically unlikely that the dominance of uniformly coloured cells in hemospheres is the result of multiple independent Cre recombination events, the observed pattern indicated clonal expansion of haematopoietic stem or progenitor cells in situ. Together with the enrichment of CD150+ CD48− cells, the early repopulation of hemospheres by transplanted BM cells as well as the particularly high local proliferation, our data strongly suggest that hemospheres represent a specialized haematopoietic microenvironment with properties that are distinct from the BM cavity.

Loss of hemospheres in the absence of endothelial VEGFR2 signalling

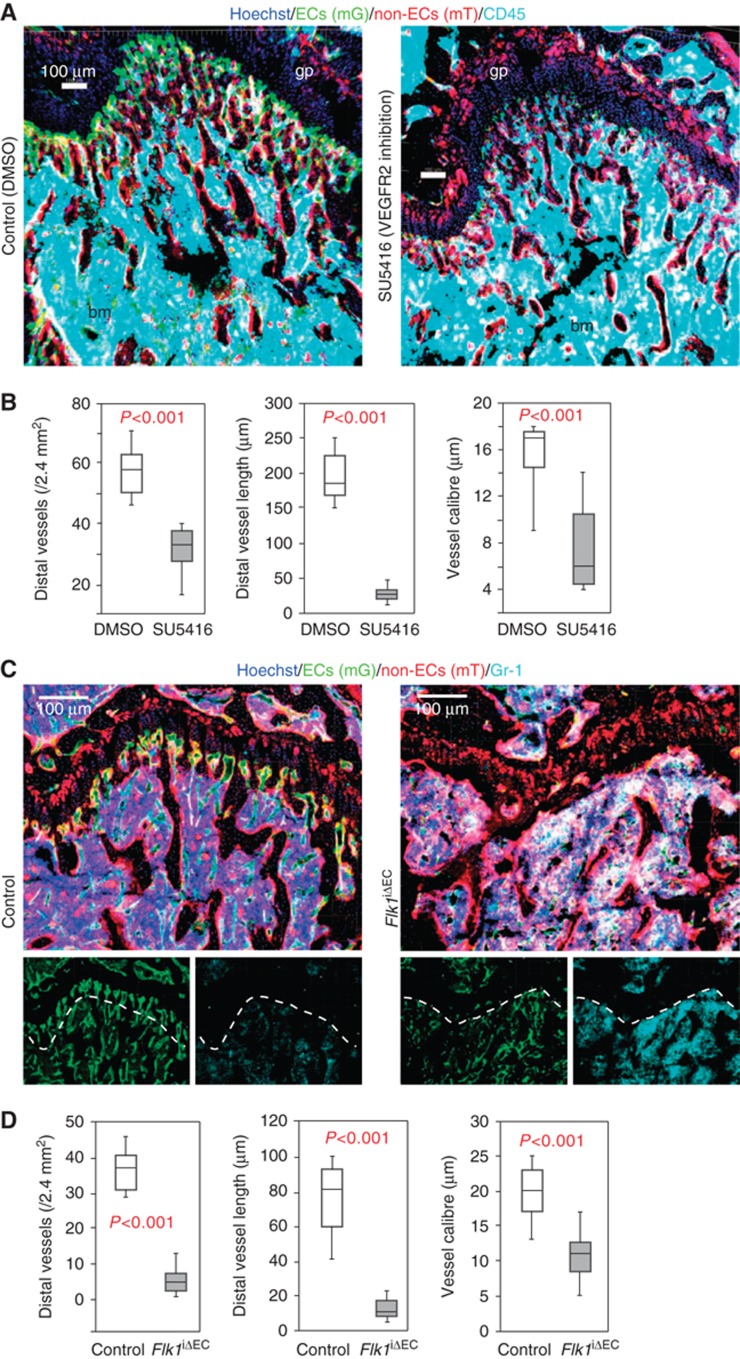

Given that hemospheres are organized around a central vessel, we next investigated the functional role of SECs in this structure. Inhibition of VEGF receptor kinase activity with suitable inhibitors is used for the targeting of vessel growth in tumours and other processes of pathological angiogenesis (Thurston and Kitajewski, 2008; Carmeliet and Jain, 2011). Indicating plasticity of the vasculature even in non-pathological situations, it has been shown that administration of VEGF pathway inhibitors can lead to vessel regression in the vasculature of adult mice and, in particular, in organs with fenestrated endothelium (Kamba et al, 2006). Sinusoidal vessels in the adult bone are fenestrated (Supplementary Figure 9A) and display a particularly high degree of VEGF-dependent vessel plasticity. Overexpression of VEGF-A in an inducible gain-of-function model (VEGF-AiGOF) (Maes et al, 2010) for as little as 4 days led to excessive sinusoidal vessel growth in the adult metaphysis (Supplementary Figure 9B). Conversely, administration of the VEGFR2 inhibitor SU5416 (Semaxanib) for 3 days led to a substantial reduction in BM vessel density in the femur, which was particularly pronounced for the most distal vessels in the metaphysis (Figure 6A and B; Supplementary Figure 9C). Short-term SU5416 administration did not disrupt the BM cavity (Figure 6A) or significantly alter the total number of haematopoietic cells.

Figure 6.

Morphological changes after loss of VEGFR2 activity. (A) Morphology of metaphysis and trabecular BM (bm) in vehicle (control) or SU5416-treated 6-week-old mice, as visualized with the indicated markers. (B) Reduction of distal vessel density and length, and capillary calibre in proximity of the growth plate of 8-week-old SU5416-treated animals. Error bars, s.e.m. (C) Morphological changes in the metaphysis of Flk1iΔEC mutants compared to control littermates (14-week-old mice), visualized with the indicated markers. Dotted line marks edge of trabecular BM. Small panels show mG (ECs, green) and Gr-1 (myeloid cells, cyan) immunosignals of the larger image above. (D) Quantitation of distal vessel density, length and capillary calibre in the Flk1iΔEC metaphysis at 14 weeks. Error bars, s.e.m.

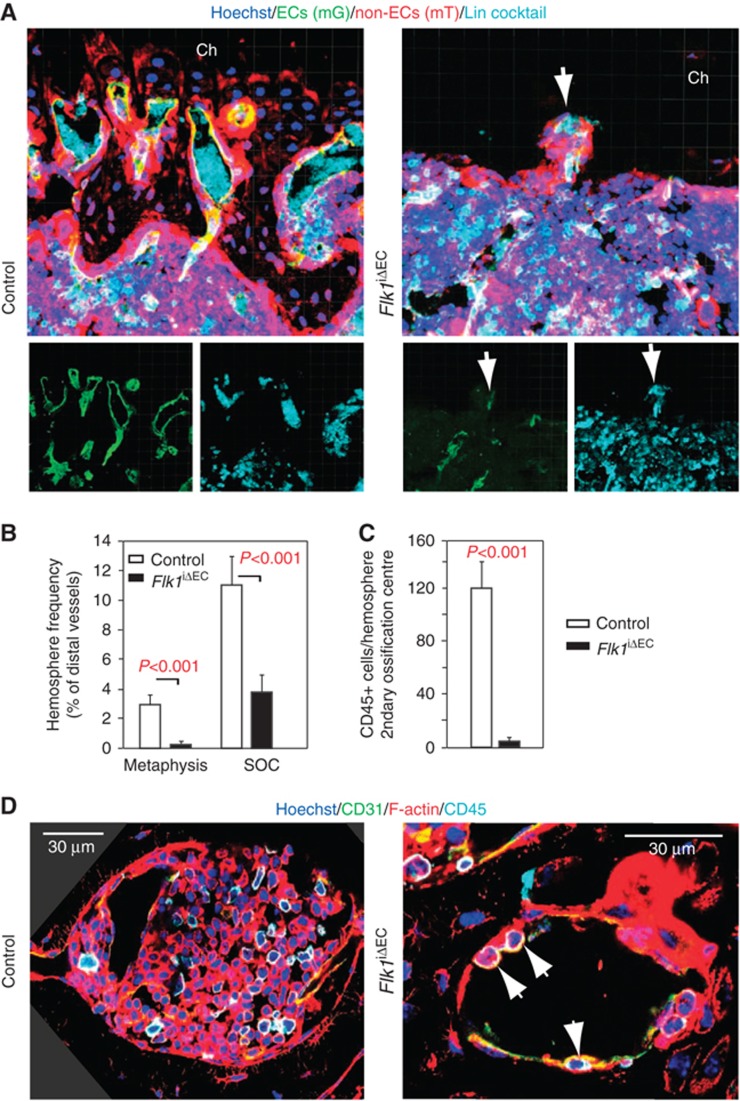

To explore the effect of prolonged loss of VEGFR2 activity and to specifically investigate the function of VEGFR2 in endothelial cells without affecting other VEGFR2-expressing cell populations such as osteoblasts and their progenitors (Deckers et al, 2000; Maes et al, 2010), we interbred mice carrying a floxed VEGFR2 (Flk1) gene with Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mT/mG double transgenics. Cre activity in Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mice was highly selective for ECs without targeting of adult haematopoietic, mesenchymal or osteoblastic cell populations (Figure 1). Triggering inactivation of Flk1 in ECs of adult animals led to a pronounced reduction of vessel density in the resulting Flk1iΔEC mutants (Figure 6C and D; Supplementary Figure 10). Organization of the metaphysis was disrupted substantially and structures resembling hemospheres were collapsed, deformed or absent (Figure 7A and B; Supplementary Figure 10). Mutant secondary ossification centres contained empty hemospheres with only a few SECs and largely devoid of CD45+ haematopoietic cells (Figure 7B–D). Indicating substantial changes in the properties of this compartment, staining with the hypoxia marker pimonidazole was strongly increased and rapid EdU labelling was no longer observed (Supplementary Figure 11A and B). As the general architecture of secondary ossification centres was preserved in the Flk1iΔEC femur, the disruption of hemospheres is likely to represent a direct effect of vessel regression and not the consequence of other, indirect changes in the surrounding tissue or in other organs. Like in SU5416-treated animals, the established BM cavity was still present in Flk1iΔEC mutants and contained a substantial amount of vessels (Figure 6C; Supplementary Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 7.

Targeting of VEGFR2 disrupts hemospheres. (A) Distal sinusoidal vessels are found in direct proximity of chondrocytes (ch) in the control metaphysis. The equivalent region is devoid of SECs and contains only a few, collapsed hemospheres (arrow) in Flk1iΔEC mutants. Small panels show mG (ECs, green) and lineage-committed haematopoietic cells (Lin cocktail, cyan) immunosignals of the larger image above. (B) Quantitation of collapsed hemospheres in the Flk1iΔEC metaphysis and secondary ossifications centres (SOC). Error bars, s.e.m. (C) Quantitation of CD45+ haematopoietic cells per hemosphere in the secondary ossification centre of adult control and Flk1iΔEC mice, as indicated. Error bars, s.e.m. (D) Hemospheres in the SOC of control animals are filled with CD31+ endothelial (green/yellow) and CD45+ (cyan) haematopoietic cells. In contrast, Flk1iΔEC hemospheres appear and contain only very few CD45+ cells (arrows). Red signal, phalloidin (F-actin). Three corners in the left panel are filled in dark grey to cover regions without image data, which are the result of image rotation.

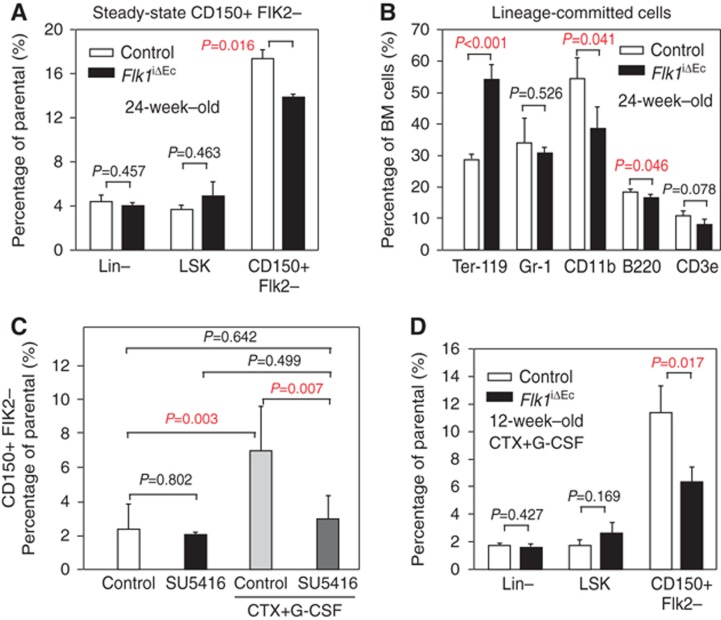

Reduced number of CD150+ Flk2− cells in EC-specific VEGFR2 mutants

The number of total, Lin− or LSK cells was not significantly altered in the Flk1iΔEC BM (Figure 8A; Supplementary Figure 12A). Likewise, despite alterations in the total number of red blood cells and CD11b+ leukocytes, major lineage-committed cell populations were maintained after targeting of Flk1 in the endothelium (Figure 8B). However, arguing for a role of hemospheres as a specialized BM compartment, flow cytometry revealed a small but significant reduction in CD150+ Flk2− cells, a subpopulation highly enriched in HSCs (Lu et al, 2011), in the Flk1iΔEC marrow (Figure 8A; Supplementary Figure 12A). A comparison of transplanted BM cells isolated from control (littermate) and Flk1iΔEC femur showed that the latter were less capable of rescuing lethally irradiated recipient mice in a short-term survival experiment (Supplementary Figure 12B).

Figure 8.

Altered putative HSC numbers after loss of VEGFR2 activity. (A) Analysis of LSK (Lin−, Sca-1+, cKit+) CD150+ Flk2− putative HSCs by multi-parametric flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 12A) in the femoral BM of 24-week-old Flk1iΔEC mutants and control littermates under steady-state conditions. Error bars, s.e.m. (B) Quantitation of lineage-committed cells isolated from 24-week-old Flk1iΔEC mutants and control littermates. Mutants showed increased Ter-119+ erythroid cells and reduced CD11b+ macrophages, while the number of B220+ B cells, CD3e+ T cells and Gr-1+ granulocytes/neutrophils/macrophages was not altered compared to littermates. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of LSK CD150+ Flk2− cells in the BM of control and SU5416-treated 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (Supplementary Figure 12C). Significant activation and mobilization of putative HSCs by CTX and G-CSF treatment was no longer obtained after SU5416 treatment. Statistics, one-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak pairwise multiple group comparison. (D) Quantitation of LSK CD150+ Flk2− putative HSCs after CTX+G-CSF mobilization in the femoral BM of 14-week-old control and Flk1iΔEC mice. Error bars, s.e.m.

HSCs can be activated and mobilized with a combination of cyclophosphamide (CTX) and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (Morrison et al, 1997; Kiel et al, 2005). This regime uncovered a significant reduction in the number of CD150+ Flk2− cells obtained from the marrow of SU5416-treated mice and EC-specific Flk1iΔEC mutants (Figure 8C and D; Supplementary Figure 12). Taken together, our data indicate important, previously unrecognized roles of endothelial VEGFR2 activity in the maintenance of the BM vasculature, hemosphere integrity and the abundance of CD150+ Flk2− cells.

Discussion

Despite the great importance of BM in the healthy organism and in disease conditions such as leukaemia (Li and Xie, 2005; Moore and Lemischka, 2006; Scadden, 2006; Morrison and Spradling, 2008), our knowledge of the spatial organization of this organ and the precise location of specific microenvironments is still insufficient. Here, we have identified a novel BM compartment with defined organization and distinct properties, the hemosphere. Hemospheres consist of an inner endothelial tube, peripheral mesenchymal cells (osteoblasts), and, enclosed in the space between these two layers, cells of the haematopoietic lineage. The presence of such structures in mouse long bone, sternum, skull and vertebrae as well as in human long bone suggests that hemospheres are structurally conserved and might represent a general compartment present in most or all marrow-containing skeletal elements. While we currently lack insight into the time course of hemosphere formation, the presence of differently sized structures suggests gradual expansion, which leads to the enlargement of the space surrounding the central endothelium and, concomitantly, an increase in the local number of haematopoietic cells.

Although it is currently technically impossible to separate and functionally characterize cells from hemospheres, several lines of evidence support that this compartment has properties that are distinct from the adjacent BM cavity. CD150+ CD48− cells, which might represent HSCs according to the SLAM code, and CD150− CD48+ progenitor cells were found in large numbers and associated with sinusoidal vessels inside hemospheres. A fraction of CD150− CD48+ cells and other, as yet unidentified cell populations inside hemospheres, displayed very high rates of local proliferation and were labelled by a short pulse of EdU administration in vivo. Fast proliferation is a feature associated with rapidly amplifying, oligo-potent or lineage-restricted progenitor cells within the haematopoietic hierarchy (Bryder et al, 2006). Genetic labelling identified hemospheres as a site of clonal haematopoietic cell expansion and transplanted, fluorescent BM cells were found inside hemosphere-like structures before they populated the remainder of the marrow cavity in transplanted animals. All these findings argue that hemospheres have specific properties and are thereby distinct from the rest of the BM cavity. It remains to be addressed whether hemospheres might actually represent specialized HSC niches or are a compartment for transit-amplifying progenitor cell specification. However, as it currently not possible to isolate, transplant or functionally characterize cells exclusively from hemospheres, it remains to be addressed whether this compartment has niche properties and can directly control the activity of haematopoietic stem or progenitor cells.

In addition to a previous report showing that VEGFR2 signalling is required for engraftment of transplanted HSC and reconstitution of haematopoiesis (Hooper et al, 2009), we now establish that this pathway plays important roles in BM homeostasis. While it cannot be ruled out that SECs and endothelial VEGFR2 signalling have multiple distinct functions in the BM, our phenotypic characterization suggests that the disruption of hemospheres is most likely a major underlying cause for the changes in haematopoietic cells within Flk1iΔEC mutant mice. Hemospheres are vessel-associated compartments and were very strongly affected in Flk1iΔEC mutant mice. Typically, we observed a complete collapse of these structures or, as in secondary ossification centres, the absence of haematopoietic cells. In contrast, the vasculature of the BM cavity was less impaired and the overall cellularity of the mutant marrow remained unaltered.

On the basis of our finding that BM contains specific structural compartments with distinct properties, future work will have to address the precise function of hemospheres and their potential roles in haematopoiesis, HSC maintenance, progenitor cell specification and clonal cell expansion.

Materials and methods

Mouse genetics

For loss-of-function experiments, Flk1floxed/floxed (Haigh et al, 2003) were combined with Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 (Wang et al, 2010) transgenic mice. The combination of the latter strain and Rosa26-mT/mG mice (Muzumdar et al, 2007) enabled the simultaneous labelling of the sinusoidal endothelium and surrounding tissues. Experiments with inducible Cre transgenics in adolescent and adult mice involved intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen solution (Sigma, T5648; 1 mg/ml; generated by diluting a 10 mg/ml tamoxifen stock solution in 1:4 ethanol:peanut oil) at a dose of 500 μg/mouse/day for 5 days into 4-week-old animals. The generation of VEGF-AiGOF mice and doxycycline-mediated induction of VEGF in the adult bone has been described previously (Maes et al, 2010). For the visualization of clonal expansion in the haematopoietic lineage, Vav1-Cre transgenics (de Boer et al, 2003) were combined with R26R-Confetti Cre reporters (Snippert et al, 2010). Mouse offspring was routinely genotyped using standard PCR protocols. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the institutional guidelines and were approved by local animal ethics committees.

Bone immunohistochemistry and laser scanning confocal microscopy

Hindlimb long bones, sternum, calvarium and vertebrae were collected from transgenic and mutant mice or age-matched littermate controls at appropriate time points. Adherent muscles were trimmed, long bone epiphyses were split into halves, and sterna were divided into 2–3 pieces for maximal exposure of the marrow cavities. Skeletal elements were initially fixed, decalcified and permeabilized in a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, pH 7.4), 10% EDTA and 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH 7.4) on ice for 4 h followed by extensive decalcification in 20% EDTA (pH 7.4) at 4°C for an additional 24 h. Bone tissues were washed with 1 × PBS, sequentially immersed in 10% (2 h), 30% (2 h) and finally 60% glycerol in PBS overnight at 4°C. Bone tissues were thus stored at −80°C or embedded in 8% gelatin (porcine) in the presence of 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP).

For experiments involving rapid EdU labelling, adult C57Bl/6 wild-type mice, Flk1iΔEC mutants or control littermates were intraperitoneally injected with 2.5 mg EdU (Invitrogen) in 100 μl PBS. Mice were sacrificed at 30 s following injection and bones were immediately dissected and transferred into fixation solution within 10 min. For metabolically labelling with the hypoxia probe pimonidazole (Pimo, Hypoxyprobe Inc.), mutant and control mice were intraperitoneally injected with 60 mg/kg Pimo in PBS. After 2 h, mice were rapidly labelled with EdU and tissues were collected immediately. Metabolized Pimo was detected by a rabbit antiserum against the non-oxidized, protein-conjugated form of pimonidazole (Hypoxyprobe Inc.).

For immunofluorescent stainings and morphological analyses, 60–100 μm thick sections were generated using low-profile blades on a Leica CM3050 cryostat. For antibody stainings that did not work on fixed or thick bone sections, thin (8 μm) cryosections were prepared. In these cases, freshly isolated distal ends of femurs were sliced longitudinally into fragments of ∼0.5 × 1.0 × 2.0 mm and fixed in 0.5% PFA in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The bone fragments were embedded in gelatin and snap-frozen in −80°C freezer. Sections were generated with a tungsten carbide blade on a Leica CM3050 cryostat.

Immunostaining, laser scanning confocal microscopy and 3D tissue reconstruction

Bone sections were air-dried, permeabilized in 0.25% Triton X-100, washed with PBS and blocked in 5% goat and/or rabbit serum at room temperature for 15 min. Blocked sections were probed with the following primary antibodies (diluted in 5% goat or donkey serum in PBS) for 1–2 h at room temperature: CD150 (1:200, R&D Systems, cat. no. MAB4330), CD48 (1:500, BD Pharmingen; 553682), NG2 (1:100, Millipore; AB5320), CD146 (1:200, Epitomics, EPR3208), PDGFRβ (1:200, eBioscience, APB5), Nestin (1:100, Santa Cruz; sc-101541), Runx2 (1:200, R&D Systems; MAB2006), Osterix (1:50, Santa Cruz, sc-22536-R), Osteopontin (OPN, 1:100, R&D Systems, AF808), N-Cadherin (1:200, R&D Systems, MAB1388), CD31 (1:500, Pharmingen; 553370) and CD45 (1:500, Becton Dickinson; 553077). Endomucin antibody was a gift of Dr Dietmar Vestweber, MPI for Molecular Biomedicine (Morgan et al, 1999). After primary antibody incubation, sections were washed with PBS for three times and incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor-coupled secondary antibodies (1:500, Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. Alexa Fluor-conjugated phalloidin was used at 1:1000 (stock at 10 mM). Cell nuclei were labelled with Hoechst 33342. Sections were thoroughly washed, air-dried and mounted with FluoroMount-G (Southern Biotech) and sealed with nail polish (RIMMEL, London).

The expression of fluorescent proteins (mTomato, mEGFP, mECYP, nEGFP, cEYFP, cERFP) or immunofluorescent stainings were analysed on a Leica SP5 inverted laser scanning confocal microscope. Conditions and parameters for signal acquisition from the R26R-Confetti-encoded fluorescent proteins were as follows: mECYP (Ex at 440 nm, laser beam at 458 nm, Em at 465–490 nm, 1.5 Airy), nEGFP (Ex at 488, laser beam at 488, Em at 500–510, 1.2 Airy), cEYFP (Ex at 515, laser beam at 514, Em at 530–550, 1.0 Airy) and cERFP (Ex at 561, laser beam at 561, Em at 590–630, 1.0 Airy). Z-stacks of images were processed and 3D reconstructed with the Imaris software (version 7.00, Bitplane).

Human femur biopsies were taken from a patient (female at the age of 13 years 8 months, Tanner pubertal stage B3) who was undergoing surgery because of medical indications. Informed consent was obtained from the patient and the parents, and approval was given by the Local Medical Ethics Committee at The Karolinska University Hospital. Paraffin sections were dewaxed and subjected to antibody staining according to standard protocols. Two-photon microscopy was performed on human femur samples using a customized 2-photon microscope (TriM Scope II, LaVision BioTec) with detection by an array of independent photo-multiplier tube (PMT) detectors with single-point illumination using a × 20 Olympus objective (NA=1.0).

Electron microscopy

For electron microscopy, the femur bone of 6-week-old mice was processed similar to a protocol published by Suzuki et al (2005) with some modifications. The bone was removed and directly transferred into 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2), cut longitudinally into two halves and fixed initially for 2 h at room temperature and overnight at 4°C under agitation. The sample was decalcified in 5% EDTA in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 3 days with one exchange of the solution after 1.5 days. The sample was post-fixed for 1.5 h in 1% OsmO4, 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide. Dehydration and embedding in epon was done under slight vacuum (Grills and Ham, 1989). In all, 70 nm ultrathin sections of the sample were taken in the area of interest and collected on filmed single slot copper grids (Leica UC6 ultramicrotome, Vienna, Austria). Sections got counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead, and were analysed at 80 kV on a FEI-Tecnai 12 electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Pictures were taken with imaging plates (Ditabis, Pforzheim, Germany).

Multiple parameter flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis of CD150+ Flk2− putative HSCs was essentially performed as previously described (Kiel et al, 2005; Wilson et al, 2008). Briefly, femurs and tibiae were collected and cleaned with kimwipes and then crushed with a sterile plastic mortar. Whole BM cells were released with Hank’s buffered salt solution supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 0.1% heparin (Invitrogen, HBSS). To obtain a single-cell suspension, cells were passed through 27.5 gauge needles twice and filtered through a nylon screen (60 μm mesh, Millipore). Cells were counted by trypan blue and a total of 10 × 106 cells were subjected to surface staining. For lineage markers staining, 1 × 106 total BM cells were used. For each staining, an equal amount of cells were included for the unstained, isotype control, or LSK staining only for subsequent gating. The cell pellets were first blocked with the BD Fc Block CD16/32 antibody (BD Pharmingen) on ice for 5 min and stained with the lineage-APC cocktail (20 μl/each, BD Pharmingen; 558074), c-Kit-PE-Cy7 (5 μl/each, BD Pharmingen; 558163), Sca-1 PerCP-Cy5-5 (5 μl/each, Invitrogen, MSCA18), Flk-2-PE (5 μl/each, BD, 553842) and CD150-AlexaFluor 488 (10 μl/each, SeroTec, MCA2274A488) simultaneously on ice for 15 min. For lineage-committed marker surface staining, the BD lineage cocktail kit (containing individual biotinylated CD3e, B220, Gr-1, CD11b and Ter-119, Pharmingen; 559971) and Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated to streptavidin were used. The stained cells were washed twice with HBSS, processed by a FACSCanto workstation and analysed with FACSDiva software (Version 6.0, BD Bioscience). Flow plots were manually compensated where necessary.

Transplantation assays

For the transient, allogenic haematopoietic cell transplantation, whole BM cells were collected from 8- to 12-week-old Rosa26-mT/mG or Vav1-Cre x R26R-Confetti transgenic mice. Cells were filtered, counted and incubated in biotinylated lineage cocktail antibodies (Pharmingen; 559971) in the microbeads buffer (Miltenyi, Biotec GmbH) at 4°C for 8 min. The antibody-conjugated BM cells were pelleted and washed with microbeads buffer, and then incubated with 20 μl magnetic microbeads at 4°C for 15 min. After negative selection with the MACS separation column, 0.8–1.0 × 105 lineage-depleted, fluorescently labelled haematopoietic cells were intrafemorally injected into 8-week-old C57Bl/6 mice that had been exposed to a lethal dose of γ irradiation (9.5 Gy, 137Cs, GammaCell), according to the method essentially described previously (Mazurier et al, 2003). Bone tissues were collected at the indicated days post transplantation.

For competitive repopulation, 8-week-old C57Bl/6 female mice were lethally irradiated within 24 h. In all, 1 × 106 GFP-expressing BM cells, which were alone insufficient to permit survival, were infused via the lateral tail vein either in combination with 1 × 106 or 2.5 × 106 BM cells derived from mutant Flk1iΔEC or littermate control animals of the indicated experimental groups. Survival of the transplanted mice was recorded daily for 34 days.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Results were analysed using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney rank sum test. Comparison among multiple groups was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak pairwise multiple group comparison procedures. P<0.05 was considered as a significant difference.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K Mildner, the staff of the MPI-MBM animal facility and A Chagin for their help and EF Wagner for the generation of Flk1 mice. Funding was provided by the Max Planck Society, the University of Muenster, and the German Research Foundation (programs SFB 492 and SPP 1190).

Author contributions: RHA conceived the project; LW performed most of the experiments; RB, HS, HC, JJH and GB generated mouse models; RB, MGB, MS, LS and FK helped with experiments and the interpretation of data; DZ generated and interpreted the EM data; RHA and LW analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C (2005) Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res 97: 512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE (1963) Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells. Nature 197: 452–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P (2011) Bone and the hematopoietic niche: a tale of two stem cells. Blood 117: 5281–5288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazsek I, Liu XH, Anjo A, Quittet P, Comisso M, Kim-Triana B, Misset JL (1995) The hematon, a morphogenetic functional complex in mammalian bone marrow, involves erythroblastic islands and granulocytic cobblestones. Exp Hematol 23: 309–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryder D, Rossi DJ, Weissman IL (2006) Hematopoietic stem cells: the paradigmatic tissue-specific stem cell. Am J Pathol 169: 338–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK (2011) Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473: 298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, Zhang L, Norotte C, Teng PN, Traas J, Schugar R, Deasy BM, Badylak S, Buhring HJ, Giacobino JP, Lazzari L, Huard J et al. (2008) A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell 3: 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, Harker N, Coles M, Tolaini M, Norton T, Williams K, Roderick K, Potocnik AJ, Kioussis D (2003) Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol 33: 314–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckers MM, Karperien M, van der Bent C, Yamashita T, Papapoulos SE, Lowik CW (2000) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors during osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinology 141: 1667–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick JE, Magli MC, Huszar D, Phillips RA, Bernstein A (1985) Introduction of a selectable gene into primitive stem cells capable of long-term reconstitution of the hemopoietic system of W/Wv mice. Cell 42: 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ (2012) Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 481: 457–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan PL, Chute JP (2012) The vascular niche: home for normal and malignant hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia 26: 54–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshkar-Oren I, Viukov SV, Salameh S, Krief S, Oh CD, Akiyama H, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Zelzer E (2009) The forming limb skeleton serves as a signaling center for limb vasculature patterning via regulation of Vegf. Development 136: 1263–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frassoni F, Testa NG, Lord BI (1982) The relative spatial distribution of erythroid progenitor cells (BFUe and CFUe) in the normal mouse femur. Cell Tissue Kinet 15: 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills BL, Ham KN (1989) Transmission electron microscopy of undecalcified bone. J Electron Microsc Tech 11: 178–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh JJ, Morelli PI, Gerhardt H, Haigh K, Tsien J, Damert A, Miquerol L, Muhlner U, Klein R, Ferrara N, Wagner EF, Betsholtz C, Nagy A (2003) Cortical and retinal defects caused by dosage-dependent reductions in VEGF-A paracrine signaling. Dev Biol 262: 225–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper AT, Butler JM, Nolan DJ, Kranz A, Iida K, Kobayashi M, Kopp HG, Shido K, Petit I, Yanger K, James D, Witte L, Zhu Z, Wu Y, Pytowski B, Rosenwaks Z, Mittal V, Sato TN, Rafii S (2009) Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell 4: 263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamba T, Tam BY, Hashizume H, Haskell A, Sennino B, Mancuso MR, Norberg SM, O'Brien SM, Davis RB, Gowen LC, Anderson KD, Thurston G, Joho S, Springer ML, Kuo CJ, McDonald DM (2006) VEGF-dependent plasticity of fenestrated capillaries in the normal adult microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H560–H576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ (2005) SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 121: 1109–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Xie T (2005) Stem cell niche: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21: 605–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord BI, Testa NG, Hendry JH (1975) The relative spatial distributions of CFUs and CFUc in the normal mouse femur. Blood 46: 65–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Neff NF, Quake SR, Weissman IL (2011) Tracking single hematopoietic stem cells in vivo using high-throughput sequencing in conjunction with viral genetic barcoding. Nat Biotechnol 29: 928–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Goossens S, Bartunkova S, Drogat B, Coenegrachts L, Stockmans I, Moermans K, Nyabi O, Haigh K, Naessens M, Haenebalcke L, Tuckermann JP, Tjwa M, Carmeliet P, Mandic V, David JP, Behrens A, Nagy A, Carmeliet G, Haigh JJ (2010) Increased skeletal VEGF enhances beta-catenin activity and results in excessively ossified bones. EMBO J 29: 424–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Kobayashi T, Kronenberg HM (2007) A novel transgenic mouse model to study the osteoblast lineage in vivo. Ann NY Acad Sci 1116: 149–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurier F, Doedens M, Gan OI, Dick JE (2003) Rapid myeloerythroid repopulation after intrafemoral transplantation of NOD-SCID mice reveals a new class of human stem cells. Nat Med 9: 959–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma'ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS (2010) Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 466: 829–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, Lemischka IR (2006) Stem cells and their niches. Science 311: 1880–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SM, Samulowitz U, Darley L, Simmons DL, Vestweber D (1999) Biochemical characterization and molecular cloning of a novel endothelial-specific sialomucin. Blood 93: 165–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Spradling AC (2008) Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 132: 598–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Wright DE, Weissman IL (1997) Cyclophosphamide/granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induces hematopoietic stem cells to proliferate prior to mobilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1908–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L (2007) A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45: 593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L (2006) VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 359–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinkevich Y, Lindau P, Ueno H, Longaker MT, Weissman IL (2011) Germ-layer and lineage-restricted stem/progenitors regenerate the mouse digit tip. Nature 476: 409–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, Di Cesare S, Piersanti S, Saggio I, Tagliafico E, Ferrari S, Robey PG, Riminucci M, Bianco P (2007) Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell 131: 324–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scadden DT (2006) The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature 441: 1075–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, van Es JH, van den Born M, Kroon-Veenboer C, Barker N, Klein AM, van Rheenen J, Simons BD, Clevers H (2010) Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143: 134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T (2006) Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 25: 977–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Amizuka N, Oda K, Li M, Yoshie H, Ohshima H, Noda M, Maeda T (2005) Histological evidence of the altered distribution of osteocytes and bone matrix synthesis in klotho-deficient mice. Arch Histol Cytol 68: 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston G, Kitajewski J (2008) VEGF and Delta-Notch: interacting signalling pathways in tumour angiogenesis. Br J Cancer 99: 1204–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtieri M, Sorrentino A (2008) The mesenchymal stromal cell contribution to homeostasis. J Cell Physiol 217: 296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, Schmidt TS, Bochenek ML, Sakakibara A, Adams S, Davy A, Deutsch U, Luthi U, Barberis A, Benjamin LE, Makinen T, Nobes CD, Adams RH (2010) Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature 465: 483–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wan C, Deng L, Liu X, Cao X, Gilbert SR, Bouxsein ML, Faugere MC, Guldberg RE, Gerstenfeld LC, Haase VH, Johnson RS, Schipani E, Clemens TL (2007) The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest 117: 1616–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, van der Wath RC, Blanco-Bose W, Jaworski M, Offner S, Dunant CF, Eshkind L, Bockamp E, Lio P, Macdonald HR, Trumpp A (2008) Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell 135: 1118–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin T, Li L (2006) The stem cell niches in bone. J Clin Invest 116: 1195–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelzer E, Olsen BR (2005) Multiple roles of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in skeletal development, growth, and repair. Curr Top Dev Biol 65: 169–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuschner D, Mildner K, Zaehres H, Scholer HR (2010) Induced pluripotent stem cells at nanoscale. Stem Cells Dev 19: 615–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.