Abstract

The Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) in complex with its co-activator Cdc20 is responsible for targeting proteins for ubiquitin-mediated degradation during mitosis. The activity of APC/C–Cdc20 is inhibited during prometaphase by the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (SAC) yet certain substrates escape this inhibition. Nek2A degradation during prometaphase depends on direct binding of Nek2A to the APC/C via a C-terminal MR dipeptide but whether this motif alone is sufficient is not clear. Here, we identify Kif18A as a novel APC/C–Cdc20 substrate and show that Kif18A degradation depends on a C-terminal LR motif. However in contrast to Nek2A, Kif18A is not degraded until anaphase showing that additional mechanisms contribute to Nek2A degradation. We find that dimerization via the leucine zipper, in combination with the MR motif, is required for stable Nek2A binding to and ubiquitination by the APC/C. Nek2A and the mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC) have an overlap in APC/C subunit requirements for binding and we propose that Nek2A binds with high affinity to apo-APC/C and is degraded by the pool of Cdc20 that avoids inhibition by the SAC.

Keywords: APC/C, Kif18A, Nek2A, spindle assembly checkpoint

Introduction

The Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) is a large E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for targeting proteins for degradation during mitosis. Despite being composed of at least 15 subunits it is absolutely dependent on one of two co-activators, Cdc20 or Cdh1, for its activity (Pines, 2011). The co-activators assist in the binding of substrates to the APC/C and recognize destruction motifs in these, the most common being D boxes or KEN boxes. D-box destruction motifs are bound by a combined interface composed of the co-activator and the APC10 subunit (Carroll and Morgan, 2002; Passmore et al, 2003; Carroll et al, 2005; Matyskiela and Morgan, 2009; Buschhorn et al, 2011; da Fonseca et al, 2011; Schreiber et al, 2011). In addition, the co-activators contain a C box that activates the APC/C (Kimata et al, 2008a) and in combination with a C-terminal IR motif contributes to the binding of co-activators to the APC/C (Passmore et al, 2003; Thornton et al, 2006). The IR motif is able to bind to TPR subunits of the APC/C while the C box is closer to the catalytic core (Wendt et al, 2001; Vodermaier et al, 2003; Matyskiela and Morgan, 2009; Buschhorn et al, 2011; da Fonseca et al, 2011; Schreiber et al, 2011).

During mitosis Cdc20 is the essential co-activator that directs the APC/C towards a range of substrates in a defined temporal manner (Pines, 2011). Cdc20 is inhibited by the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (SAC), a surveillance mechanism ensuring proper chromosome segregation (Musacchio and Salmon, 2007; Nilsson, 2011). The SAC is activated by improperly attached kinetochores and this leads to the binding of the three checkpoint proteins, Mad2, BubR1 and Bub3 to Cdc20, forming the mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC) (Hardwick et al, 2000; Sudakin et al, 2001; Tang et al, 2001; Fang, 2002; Nilsson et al, 2008). The MCC exists either as a free complex or in complex with the APC/C (Sudakin et al, 2001; Morrow et al, 2005; Herzog et al, 2009) via an interaction with the APC8 subunit of the APC/C (Izawa and Pines, 2011). Exactly how Cdc20 is inhibited when in complex with checkpoint proteins is not clear although the BubR1 protein has been proposed to act as a pseudo-substrate, preventing the binding of substrates to Cdc20 (Burton and Solomon, 2007; Lara-Gonzalez et al, 2011). In agreement with this BubR1 interacts with the propeller domain of Cdc20, which would otherwise bind destruction motifs in substrates (Tang et al, 2001; Kraft et al, 2005; Kimata et al, 2008b; Chao et al, 2012). An additional inhibitory mechanism is that Cdc20 becomes a substrate of the APC/C when part of the MCC and this contributes to maintain the SAC (Pan and Chen, 2004; Nilsson et al, 2008).

Despite the strong inhibition of Cdc20 by the SAC, certain proteins such as Nek2A and Cyclin A escape this inhibition and are degraded during prometaphase in a Cdc20-dependent manner (Hames et al, 2001; Elzen den and Pines, 2001; Hayes et al, 2006; Wolthuis et al, 2008; Di Fiore and Pines, 2010). Recent work has shown that Cyclin A has high affinity for Cdc20 and can compete with BubR1 for binding to Cdc20 (Di Fiore and Pines, 2010). This property of Cyclin A in combination with direct targeting of the Cyclin A–Cdk1–Cks complex to the APC/C via the Cks subunit allows Cyclin A to be degraded during an active checkpoint (Wolthuis et al, 2008; Di Fiore and Pines, 2010). Nek2A harbours an MR dipeptide at its extreme C terminus that resembles the IR dipeptide found in the co-activators Cdc20 and Cdh1 (Hayes et al, 2006). This MR dipeptide allows Nek2A to bind directly to the APC/C independently of Cdc20 and is required for Nek2A degradation during an active SAC (Hayes et al, 2006). The direct binding of Nek2A bypasses the requirement for the substrate binding propeller domain of Cdc20 and indeed the C-box motif of Cdc20 is sufficient to promote Nek2A degradation (Kimata et al, 2008a). It is however not clear whether the MR dipeptide-mediated interaction with the APC/C is sufficient for degradation during an active SAC, nor whether the MCC and Nek2A can bind simultaneously to the APC/C.

Here, we describe the identification of Kif18A as a novel substrate of the APC/C–Cdc20 complex that contains a C-terminal LR dipeptide, which we show is required for binding to the APC/C and for Kif18A degradation. In contrast to Nek2A, Kif18A is not degraded until anaphase, which shows that additional mechanisms contribute to Nek2A degradation during an active SAC. Indeed, we find that C-terminal fragments of Nek2A harbouring the MR motif are not degraded until anaphase and to escape SAC inhibition Nek2A requires dimerization through its leucine zipper. Dimerization of Nek2A is required for stable binding to the APC/C but Nek2A is not able to compete with the MCC and instead binds to the apo form of the APC/C. We propose that stable binding of Nek2A to apo-APC/C is required for efficient degradation by the small amounts of Cdc20 that escape inhibition by the SAC.

Results

Kif18A binds to the APC/C through a C-terminal LR motif

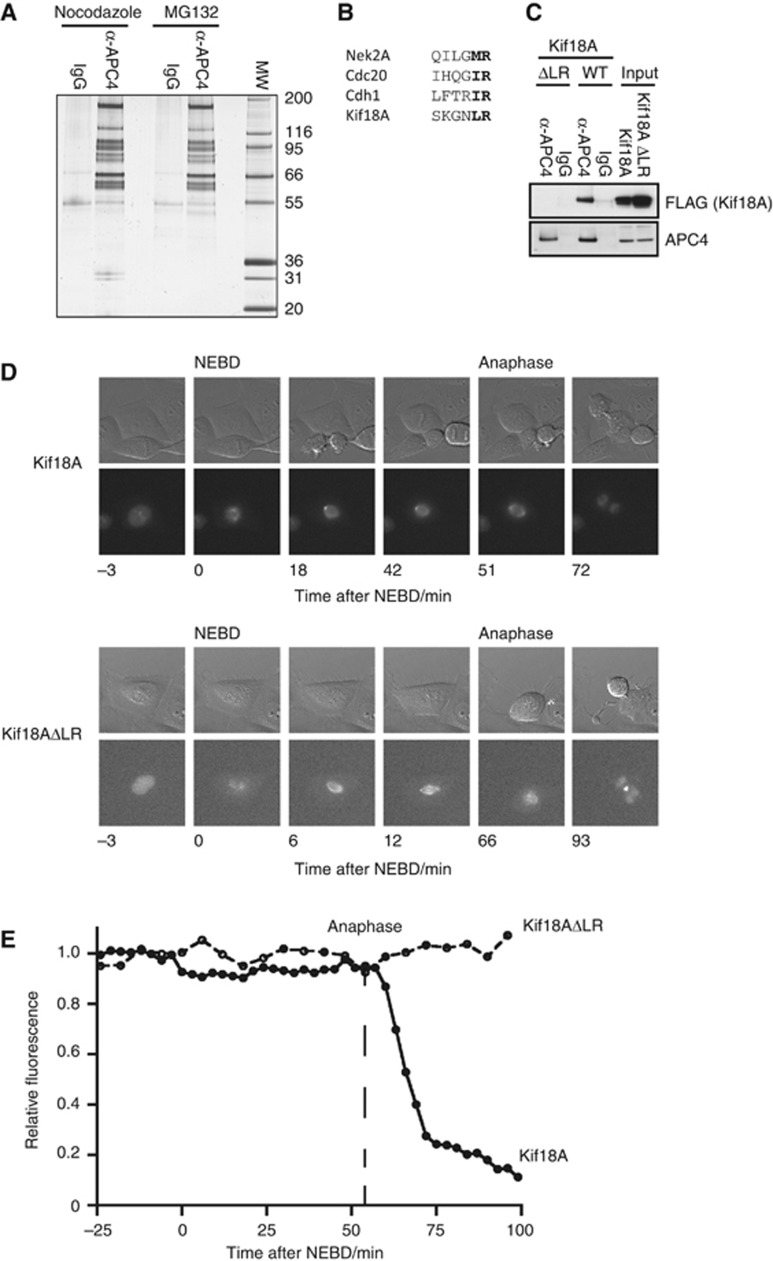

To identify novel APC/C interactors during mitosis, we performed affinity purifications of the complex from HeLa cells using a monoclonal antibody towards the APC4 subunit followed by peptide elution. The APC/C was purified from nocodazole-arrested cells and cells that were released from nocodazole into medium containing the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 1A). These, and control preparations, were analysed by mass spectrometry. In APC/C purifications from both conditions we identified two peptides of the kinesin Kif18A and in the sample from cells in metaphase we identified 14 peptides of Nek2A.

Figure 1.

Kif18A binds the APC/C through a C-terminal LR motif. (A) The APC/C complex was affinity purified using an APC4 antibody from nocodazole-arrested cells or cells released from nocodazole into MG132 for 2 h. A fraction of the sample was analysed by silver stain and the remaining sample analysed by mass spectrometry. (B) The amino-acid sequence of the last six amino acids from human Nek2A, Cdc20, Cdh1 and Kif18A is shown. (C) Stable HeLa cell lines expressing FLAG-tagged Kif18A or Kif18AΔLR were arrested with nocodazole and the APC/C complex purified using an APC4 antibody. The binding of Kif18A proteins was analysed by blotting for FLAG. (D) HeLa cells in G2 were injected with plasmids expressing Venus–Kif18A or Venus–Kif18ΔLR fusion proteins and mitotic progression was followed by time-lapse microscopy recording DIC and the Venus signal every 3 min. (E) The total Venus fluorescence was measured and plotted for each construct. At least five cells were analysed for each fusion protein.

Inspection of the human Kif18A sequence revealed that the two C-terminal residues were leucine-arginine (LR), which resembles the IR motif and MR motif found in the APC/C co-activators Cdh1, Cdc20 and Nek2A, respectively (Figure 1B). To investigate whether the LR motif in Kif18A had a role in APC/C binding, we created stable HeLa cell lines expressing inducible FLAG-tagged Kif18A or Kif18A where we deleted the last two residues (Kif18AΔLR). From these cell lines arrested in prometaphase we purified the APC/C using the APC4 antibody and monitored Kif18A binding using a FLAG antibody. We found that full-length Kif18A could be co-purified with the APC/C but removal of the C-terminal LR motif greatly reduced the interaction (Figure 1C).

To determine when Kif18A is degraded during mitosis we employed a live-cell imaging approach in which Venus-tagged Kif18A constructs were injected into HeLa cells and the total Venus fluorescence used as a read-out of protein stability as cells progress through mitosis (Clute and Pines, 1999). In agreement with characterizations of endogenous Kif18A (Mayr et al, 2007), the protein was stable throughout mitosis but was rapidly degraded at anaphase onset and this depended on its LR motif (Figure 1D and E). To determine whether Kif18A contained additional degradation motifs, we used a similar approach and analysed the degradation of various truncations: Venus-tagged Kif18A 453–898, 653–898 and 800–898. While the Kif18A 453–898 fragment was still degraded at anaphase the two other fragments were stable indicating that the region from 453 to 653 contains motifs required for degradation (Supplementary Figure S1A).

Together, these results show that Kif18A binds the APC/C and its degradation at anaphase depends on both a C-terminal LR motif and motifs between residues 453 and 653.

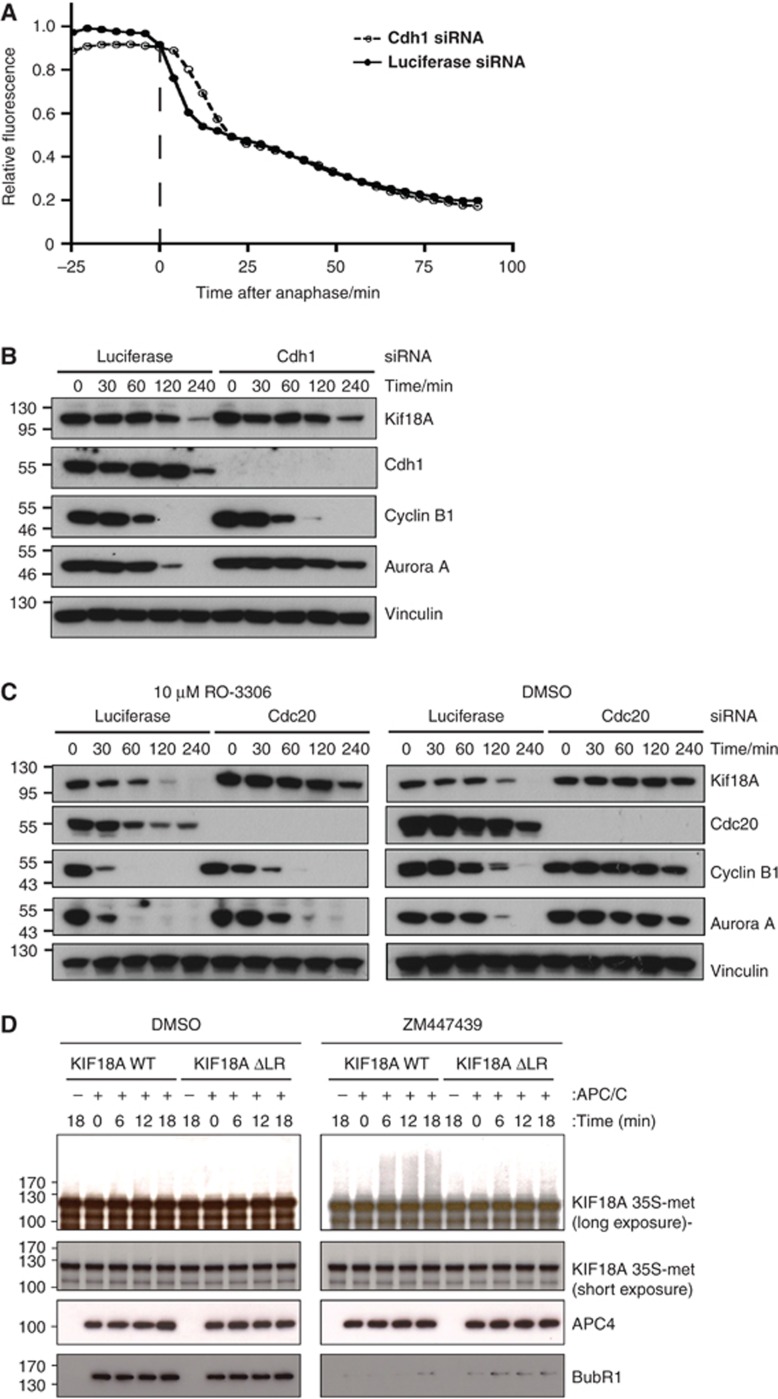

Cdc20 is required for Kif18A degradation at anaphase

The initiation of Kif18A degradation at anaphase could indicate a specific requirement for the co-activator Cdh1 for Kif18A degradation as Cdh1 can only activate the APC/C when CDK1 activity is low (Kramer et al, 2000). To investigate this, we depleted Cdh1 by RNAi and analysed the impact this had on degradation of Venus–Kif18A stably expressed in U2OS cells. Compared to control treated cells we detected no inhibition of Venus–Kif18A degradation when cells were treated with Cdh1 RNAi (Figure 2A). In a similar approach, cells treated with a control RNAi oligo or a Cdh1 RNAi oligo were released from a nocodazole block and samples collected for western blot analysis at different times following release. Although Cdh1 was efficiently depleted this had no effect on the degradation of Kif18A but did delay the degradation of Aurora A, a Cdh1 substrate (Figure 2B; Floyd et al, 2008; García-Higuera et al, 2008). However, when we depleted Cdc20 and forced cells out of mitosis with the CDK1 inhibitor RO3306 (Vassilev et al, 2006) and monitored Kif18A degradation by western blotting, Kif18A was clearly stabilized (Figure 2C). To determine whether the APC/C–Cdc20 complex was directly able to ubiquitinate Kif18A, we employed an in vitro APC/C ubiquitin ligase assay using in vitro translated Kif18A as a substrate. In these assays, APC/C purified from checkpoint-arrested cells or cells released from the checkpoint using the Aurora B inhibitor ZM447439 (Ditchfield et al, 2003) were used and the Cdc20 that co-purified was responsible for the observed in vitro activity (Supplementary Figure S1B). We found that APC/C–Cdc20 was able to ubiquitinate Kif18A and this was dependent on both the LR motif in Kif18A and sensitive to the SAC (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Kif18A is ubiquitinated by the APC/C–Cdc20 complex. (A) A stable U2OS cell line expressing FLAG–Venus-tagged Kif18A was treated with control RNAi oligo or Cdh1 RNAi oligo and cells were analysed as they progressed through mitosis by time-lapse microscopy recording every 4 min. Total Venus fluorescence was quantified at each time point and the average curve of five cells per condition is shown. (B) Control-depleted or Cdh1-depleted HeLa cells were released from a nocodazole block and samples collected at the indicated time points and analysed for the levels of the indicated proteins by western blot. (C) Control-depleted or Cdc20-depleted HeLa cells were released from a nocodazole block and seeded into fresh medium containing DMSO or 10 μM RO-3306 and samples collected at the indicated time points and analysed by western blot. (D) HeLa cells were treated with taxol (100 ng/ml) for 16 h and 5 μM MG132 was added for 2 h either with or without 3 μM ZM447439 and cells collected by mitotic shake-off. The APC/C was purified using an APC4 antibody and used for in vitro ligase assays where 35S-methionine labelled (35S-met) Kif18A or Kif18A ΔLR were used as substrates. The extent of ligation was determined by autoradiography, high and low exposures are shown. APC4 and BubR1 levels were determined in parallel by western blot analysis of a small fraction of the reaction.

We conclude from these data that Kif18A is a novel APC/C–Cdc20 substrate at anaphase. Although it was possible that Kif18A could play a role in localizing the APC/C to the mitotic spindle we did not observe an effect on APC/C spindle localization in Kif18A-depleted cells (Supplementary Figure S2).

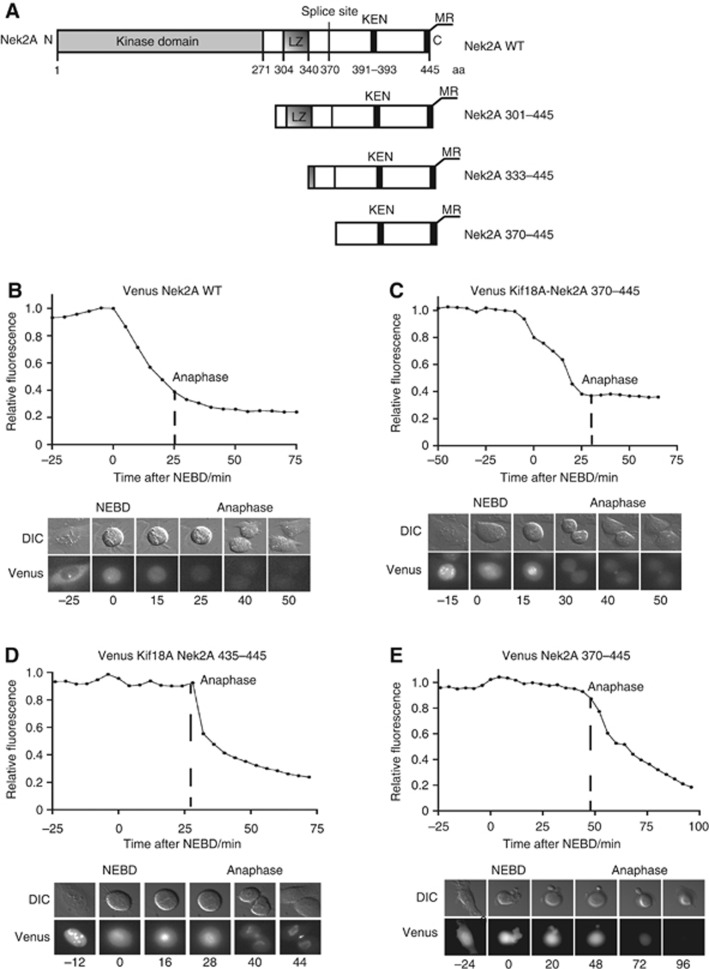

The leucine zipper of Nek2A is required for degradation during an active SAC

Our observation that Kif18A was not degraded until anaphase, despite it showing characteristics similar to Nek2A, raised the question of whether the MR motif in Nek2A was sufficient to target it for degradation during an active checkpoint. Nek2A and Nek2B are splice variants and while Nek2B is stable during prometaphase Nek2A contains an additional terminal exon encoding amino acids 370–445 that allows it to be degraded at nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) (Figure 3A and B). To determine whether this region would target Kif18A for degradation during an active checkpoint, we generated a chimeric Kif18A-Nek2A 370–445 fusion and compared it to a construct in which the last 10 amino acids of Kif18A were changed to that of Nek2A. We then created stable isogenic inducible U2OS cell lines that expressed Venus-tagged Kif18A-Nek2A 370–445 and Kif18A-Nek2A 435–445 and used the total fluorescent intensity of the Venus tag as a marker for degradation of these forms of Kif18A. While Kif18A-Nek2A 435–445 was degraded at anaphase Kif18A-Nek2A 370–445 was efficiently degraded at NEBD (Figure 3C and D). Surprisingly when we analysed the degradation of Venus Nek2A 370–445 this was not degraded until anaphase (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

The C terminus of Nek2A can target Kif18A for degradation during an active checkpoint. (A) Schematic of Nek2A primary sequence and truncation constructs analysed. (B–E) Stable U2OS/FRT/TRex cell lines expressing the indicated proteins were analysed by time-lapse microscopy and DIC and Venus signal recorded at the intervals indicated. The total fluorescence was determined for each time point and indicated in the plot with reference to the peak intensity, which is set to one. At least five cells in two independent experiments have been analysed for each fusion protein and a representative curve is shown. (B) Venus Nek2A WT (C) Venus Kif18A-Nek2A 370–445 (D) Venus Kif18A Nek2A 435–445, (E) Venus Nek2A 370–445.

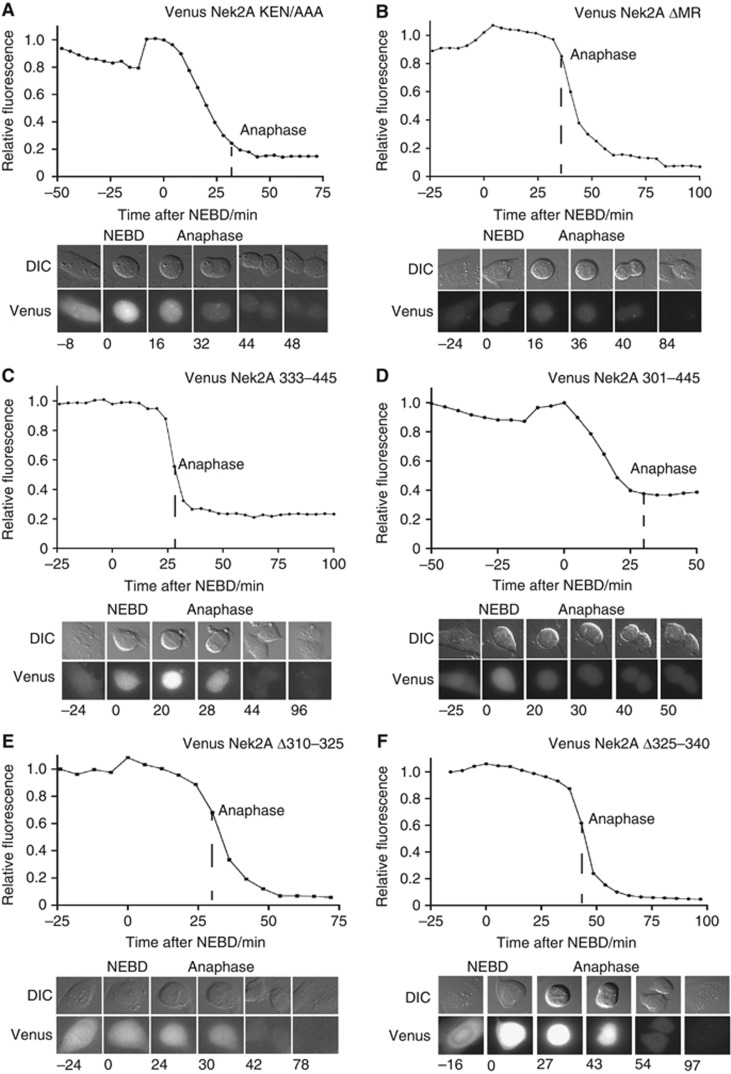

To understand how Nek2A 370–445 could target a protein for degradation at NEBD despite being an anaphase substrate itself we reinvestigated Nek2A degradation. We created isogenic stable U2OS cells that expressed different inducible Venus–Nek2A constructs. Nek2A is a dimer (Fry et al, 1999) so we made the Venus–Nek2A constructs resistant to RNAi depletion of Nek2A to avoid effects through dimerization with the endogenous protein. Due to the variation in the time it takes to align the chromosomes on the metaphase plate cells spend different times in prometaphase but all the Nek2A constructs analysed below initiated degradation as specified irrespective of how long they spend in prometaphase. In agreement with previous observations, we observed that Venus–Nek2A started to be degraded at NEBD and this depended on the C-terminal MR motif but not a KEN box present in 370–445 (Figures 3B, 4A and B). The Venus–Nek2AΔMR construct was efficiently degraded at anaphase likely due to the presence of additional destruction motifs. When we compared the degradation of Nek2A 370–445, Nek2A 333–445 and Nek2A 301–445 it was clear that including the leucine zipper of Nek2A changed the degradation profile from anaphase to NEBD (Figures 3A, E, 4C and D). To address whether the leucine zipper was required for degradation of Nek2A at NEBD in the context of the full-length protein, we made 15 amino acids deletions in that region and analysed the degradation pattern. In a manner similar to the wild-type protein, Venus Nek2A Δ280–295, with a deletion just outside the leucine zipper, was degraded at NEBD (Supplementary Figure S3) but both Nek2A Δ310–325 and Nek2A Δ325–340 were degraded at anaphase (Figure 4E and F) revealing that an intact leucine zipper is required.

Figure 4.

Nek2A degradation during prometaphase requires the leucine zipper and the MR motif. (A–F) Stable U2OS/FRT/TRex cell lines expressing the indicated Nek2A proteins were analysed by time-lapse microscopy and DIC and Venus signal recorded at the intervals indicated. The total fluorescence was determined for each time-point and indicated in the plot with reference to the peak intensity, which is set to one. At least five cells in two independent experiments have been analysed for each fusion protein and representative curves are shown. (A) Venus Nek2A KEN/AAA, (B) Venus Nek2A ΔMR (C) Venus Nek2A 333–345 (D) Venus Nek2A 301–445 (E) Venus Nek2A Δ310–325 (F) Venus Nek2A Δ325–340.

Our results show that for Nek2A to be degraded during an active checkpoint it needs both the C-terminal MR motif and its leucine zipper. Deletion of either one of these motifs shifts the degradation to anaphase.

Dimerization of Nek2A is required for its degradation during an active checkpoint

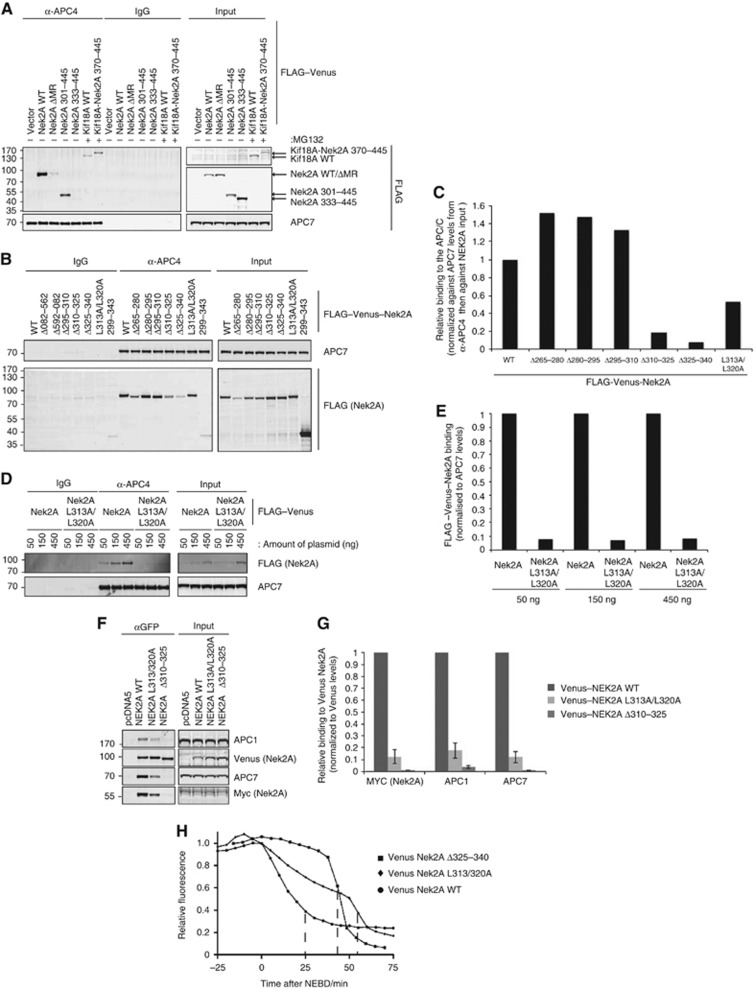

To understand why the leucine zipper was required for Nek2A degradation during an active checkpoint, we analysed the ability of the different Nek2A constructs to bind to the APC/C. Nek2A and Kif18A constructs were transfected into HeLa cells and the APC/C purified from nocodazole-arrested cells (Figure 5A–C). From these experiments, it was clear that both the C-terminal MR motif and leucine zipper of Nek2A were required for high affinity binding to the APC/C, even though the leucine zipper alone did not bind to the APC/C (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Nek2A must dimerize through its leucine zipper to bind to the APC/C when the spindle checkpoint is active. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 500 ng of the indicated FLAG–Venus–Nek2A or Kif18A fusion expression constructs and arrested in prometaphase by treatment with 200 ng/ml nocodazole for 18 h. The APC/C was immunoprecipitated using anti-APC4 antibodies and blots were probed with a FLAG antibody to assay binding of the specified FLAG–Venus fusion proteins. (B) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of the indicated FLAG–Venus–Nek2A expression constructs, treated with nocodazole for 18 h and then collected by shake-off. The APC/C was immunoprecipitated using anti-APC4 antibodies. Binding of Nek2A proteins was determined by probing with FLAG antibodies and then quantified by Licor. (C) Bar graph comparing binding of the indicated FLAG–Venus–Nek2A proteins to the APC/C after normalization against APC7 and then FLAG inputs. (D) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with increasing amounts of FLAG–Venus–Nek2A WT or L313/L320A expression constructs and treated with nocodazole for 18 h. After APC/C immunoprecipitation with anti-APC4, FLAG–Venus–Nek2A binding was determined using an anti-FLAG antibody. (E) Bar chart comparing relative binding between Nek2A WT and Nek2A L313A/L320A after normalization to APC7 levels. (F) The indicated FLAG–Venus–Nek2A fusion proteins were purified using GFP-Trap beads for 1 h, binding of Myc–Nek2A or the APC/C was determined by Licor using anti-Myc, anti-APC1 and anti-APC7 antibodies. (G) Relative binding of Myc–Nek2A, APC1 and APC7 to FLAG–Venus–Nek2A WT, Nek2A L313A/L320A or Nek2A Δ310–325 after normalization to FLAG–Venus–Nek2A levels. Data are mean±s.d. (n=3) and FLAG–Venus–Nek2A WT is set to 1. (H) Representative degradation curves of Venus Nek2A WT, Venus Nek2A L313A/L320A and Nek2A Δ325–340. Ten cells from two independent experiments were analysed for Nek2A L313A/L320A.

As the leucine zipper mediates dimerization of Nek2A we wanted to address whether Nek2A had to be a dimer to bind with high affinity to the APC/C. We mutated two critical leucine residues in the leucine zipper predicted to be required for dimerization (Croasdale et al, 2011), L313A/L320A, and analysed the ability of this mutant to bind the APC/C. At high expression levels, there was still detectable binding of Nek2A L313A/L320A to the APC/C although it was reduced compared to wild type (Figure 5B and C). However, at lower levels of expression Nek2A L313A/L320A was strongly impaired in binding to the APC/C (Figure 5D and E). We also performed purifications of Nek2A, Nek2A L313A/L320A and Nek2A Δ310–325 and analysed the binding both to APC/C and to myc-tagged Nek2A. Again Nek2A L313A/L320A and Nek2A Δ310–325 were strongly impaired in binding to the APC/C and this correlated exactly with the level of binding to myc–Nek2A (Figure 5F and G). When we analysed the degradation pattern of Nek2A L313A/L320A it initiated at NEBD with a slower initial rate than wild-type Nek2A (Figure 5H), suggesting an intermediate phenotype between that of Nek2A and Nek2A Δ310–325/Nek2A Δ325–340.

Our results establish that dimerization of Nek2A is critical for high affinity binding to the APC/C and efficient degradation during an active checkpoint.

Nek2A binds apo-APC/C during prometaphase

There was a clear correlation between the affinity of the different Nek2A constructs for the APC/C and their degradation during an active SAC. As the MCC binds with high affinity to the APC/C, Nek2A might have to compete with the MCC for a common binding site on the APC/C. Potential support for this might be provided by the observation that Nek2A was sensitive to the presence of the MCC in in vitro ubiquitination assays (Supplementary Figure S4A; and see also Herzog et al, 2009).

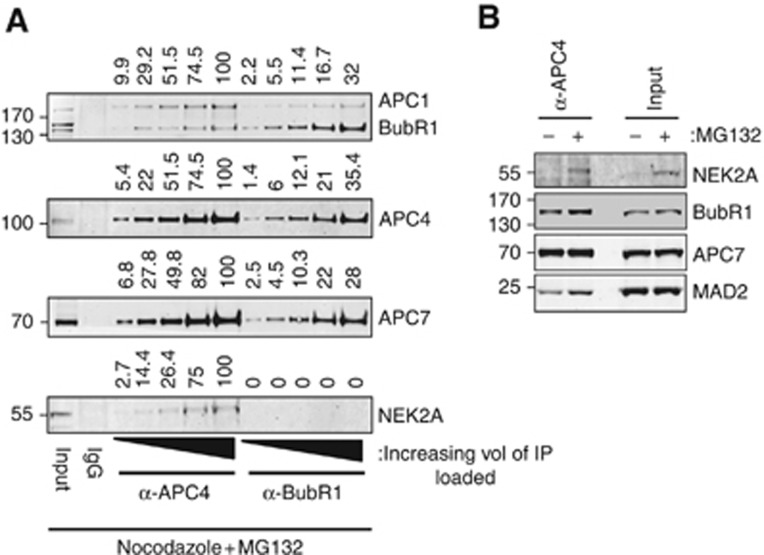

To explore the concept of Nek2A competition with the MCC, we first determined whether Nek2A could bind to the APC/C–MCC complex. We compared the binding of endogenous Nek2A to APC/C purified from HeLa cells treated with MG132 using either an APC4 antibody or to APC/C–MCC purified using a BubR1 antibody. The APC/C purified using an APC/C antibody is an ∼1:1 mixture of apo-APC/C and APC/C–MCC (Herzog et al, 2009). Different amounts of APC/C were analysed by western blotting and it was clear that Nek2A was only present in APC4 purifications, indicating that Nek2A and the MCC did not bind simultaneously to the APC/C (Figure 6A). To determine whether Nek2A was able to displace the MCC from the APC/C, we overexpressed Nek2A more than a 100-fold above its endogenous levels and analysed MCC binding to the APC/C. We only observed a slight decrease in MCC binding upon overexpression of Nek2A in two out of five experiments, indicating that competition with the MCC was an unlikely mechanism by which Nek2A escapes SAC inhibition (Supplementary Figure S4B). To determine whether Nek2A had to be recruited to the APC/C before prometaphase or could also bind once the SAC was activated, we exploited the observation that Nek2A levels increased during a mitotic arrest when the proteasome was blocked with MG132 (Figure 1A). Nocodazole-arrested cells were either treated with DMSO or MG132 and after 2 h the APC/C was purified. This experiment revealed that Nek2A produced during prometaphase could bind to the APC/C (Figure 6B). Taken together, our results clearly suggest that Nek2A binds the apo form of the APC/C during prometaphase.

Figure 6.

Nek2A binds to the apo-APC/C during prometaphase. (A) APC4 and BubR1 were immunoprecipitated from HeLa cells that were collected by shake-off after treatment with nocodazole (200 ng/ml) for 18 h and 5 μM MG132 for 2 h. Increasing amounts of each IP were loaded. Blots were probed with the indicated antibodies and quantified by Licor. Above each lane, the relative amount of signal is indicated with respect to the maximum signal for APC1, APC4, APC7 and Nek2A. (B) U20S cells were treated for 18 h with nocodazole (200 ng/ml). Mitotic cells were collected by shake-off and incubated in nocodazole ±5 μM MG132 for 2 h and then harvested by shake-off. The APC/C was purified using anti-APC4 antibodies and co-immunoprecipitated endogenous Nek2A was detected using anti-Nek2 antibodies.

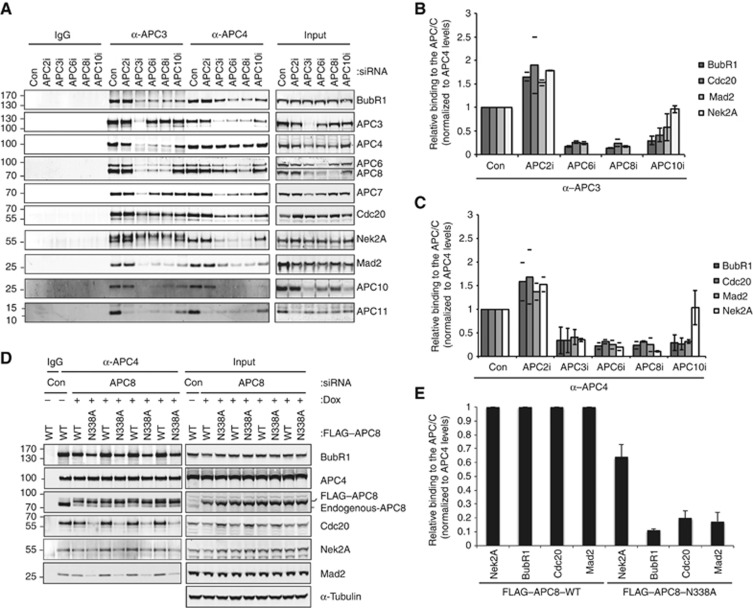

Nek2A interaction with the APC/C depends on APC8

To gain further insight into how Nek2A interacts with the APC/C during prometaphase to become an efficient substrate, we analysed its interaction with the APC/C. We depleted each of three TPR subunits, APC3, APC6 and APC8, the catalytic APC2 subunit or the substrate binding subunit APC10 and determined the effect on Nek2A binding in APC3 and APC4 purifications (Figure 7A–C). Depletion of any TPR subunit under our conditions, which have a higher ionic strength binding buffer compared to a previous study (Izawa and Pines, 2011), severely impaired binding of both Nek2A and MCC while APC10 depletion specifically affected MCC binding (Figure 7A–C). When we analysed the interdependencies of the different TPR subunits we observed that the stability of the entire TPR subunit cluster appeared to depend on all the individual subunits being present (Supplementary Figure S5) making it difficult to determine if Nek2A was binding to a single specific TPR subunit. However, the fact that Nek2A was absent from APC3 purifications when we depleted APC6 or APC8 suggested that APC3 could not be the direct receptor for Nek2A and pointed to a role for APC6 and APC8. To investigate this, we turned to a recently described mutation in the APC8 subunit, APC8 N338A, which affects MCC binding (Izawa and Pines, 2011) and analysed whether this also affected Nek2A binding. We depleted APC8 and replaced it with either FLAG–APC8 WT or FLAG–APC8 N338A. As reported, MCC binding was strongly reduced in APC8 N338A and Nek2A binding was also reduced although to a lesser extent (Figure 7D and E). In conclusion, the interaction between Nek2A and the APC/C is at least in part mediated by APC8 but interestingly the APC10 subunit involved in recognition of destruction motifs is not required.

Figure 7.

Nek2A and the MCC require the TPR subunits for binding to the APC/C and share a common binding site on APC8. (A) A double knockdown approach to deplete the indicated APC/C subunits was performed on HeLa cells. Following double thymidine synchronisation, cells were released into nocodazole (200 ng/ml). The APC/C was immunoprecipitated using anti-APC4 or anti-APC3 antibodies and blots were probed with the indicated antibodies and quantified by Licor. APC11 levels were used to determine that the APC2 depletion had worked. (B) Bar graph indicating the amount of MCC or Nek2A binding to anti-APC3 immunoprecipitates after treatment with the indicated siRNAs. Blots were quantificated by Licor and normalized against APC3 levels. Mean of two independent experiments where individual values from each independent experiment are denoted by a line (APC2, APC6, APC8), error bars indicate mean±s.d. of four independent experiments (APC10). (C) As (B) but displaying MCC and Nek2A binding after APC4 immunoprecipitation and normalization against APC4 levels. Mean of two experiments where individual values from each independent experiment are denoted by a line (APC2, APC6, APC8), error bars indicate mean±s.d. of four (APC3, APC10) experiments. (D) HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG–APC8 WT or FLAG–APC8 N338A were treated with the indicated siRNAs, synchronized with a double thymidine block and released into nocodazole (200 ng/ml)+5 μM MG132±doxycycline (20 ng/ml) then collected by shake-off after 18 h. APC/C complexes were immunoprecipitated using an anti-APC4 antibody and MCC or Nek2A binding was quantified using Licor. (E) Bar graph indicating levels of MCC or Nek2A binding after normalization against APC4 levels. Binding to FLAG–APC8 WT is set to 1. Error bars, mean±s.d. from four experiments.

Discussion

Here, we have analysed how substrates containing ‘IR-like’ motifs are degraded during mitosis. We describe Kif18A as a novel substrate that uses a C-terminal LR motif to be targeted by APC/C–Cdc20 for degradation at anaphase. Although APC/C–Cdc20-dependent degradation of Nek2A depends on a similar C-terminal MR motif we show that this is insufficient for escaping the SAC. Nek2A instead requires both its leucine zipper for dimerization and the MR motif to stably bind the apo-APC/C and these are required to escape the SAC. We favour the idea that the small amounts of Cdc20 escaping inhibition by the SAC promote Nek2A degradation and this requires stable association of Nek2A with the apo-APC/C.

Degradation of Kif18A at anaphase

Kif18A is an interesting APC/C–Cdc20 substrate in that it binds in prometaphase but is not degraded until anaphase, indicating that substrate recruitment to the APC/C is not sufficient for degradation. As Cyclin B1 and Securin start to be degraded at metaphase when the SAC becomes satisfied (Clute and Pines, 1999; Hagting et al, 2002) the fact that Kif18A is not degraded at this stage despite being able to bind suggests that additional inhibitory activities restrain APC/C–Cdc20 activity towards Kif18A until anaphase. It was recently shown that Cdc20 phosphorylations on Cdk1 sites regulate its ability to activate the APC/C (Labit et al, 2012) and as Cdk1 substrates are dephosphorylated at anaphase (Gavet and Pines, 2010) it could be that this alters Cdc20 activity at anaphase allowing Kif18A degradation. Interestingly, Kif18A binds the PP1 phosphatase in the region from 453 to 653 that we find is required for degradation (Colland et al, 2004; Meadows et al, 2011) and it will be important to determine if this interaction influences APC/C–Cdc20 activation and Kif18A degradation.

In many aspects, Kif18A and Nek2A resemble each other as APC/C substrates in that they are both dimers (Fry et al, 1999; Du et al, 2010), they both contain a C-terminal ‘IR like’ motif and they both depend on APC/C–Cdc20 for degradation. Despite this the timing of their degradation is markedly different. Since we found that Kif18A can be degraded during an active checkpoint if fused to Nek2A (370–445) there are potentially motifs in the region of Nek2A spanning residues 370–445 that mediate its escape from SAC inhibition.

Interaction of Nek2A with the APC/C and degradation during an active SAC

Our efforts to determine how Nek2A escapes the SAC have uncovered a complex picture. We find that dimerization of Nek2A via the leucine zipper is required for it to be degraded during prometaphase. The ability of Nek2A to dimerize corresponds exactly with the ability of Nek2A to bind stably to the APC/C, however, we find no evidence that dimerization-mediated binding is able to compete with the MCC for the APC/C despite the fact that their binding specificities overlap in part.

Why Nek2A has to be a dimer to bind stably to the APC/C is not clear but we envision two possibilities. First, both MR motifs in the Nek2A dimer bind to TPR subunits on the APC/C simultaneously and in a cooperative manner or second there is only one MR binding site and the increase in binding of the dimer is due to avidity. Avidity effects due to dimerization by a leucine zipper have been reported in DYNLL (LC8 dynein light chain) binding partners; dimerization results in a 200-fold increase in affinity largely due to a much lower off-rate (Radnai et al, 2010). Whether dimerization mediated stable APC/C binding is used by other substrates or regulators will be interesting to test.

Materials and methods

Cloning and generation of stable cell lines

Kif18A and Kif18ΔLR were amplified by PCR from GFP Kif18A (Mayr et al, 2007) and inserted into the BamHI and NotI sites of pcDNA5/FRT/TO FLAG and subcloned from here into pcDNA5/FRT/TO FLAG Venus or pRSET A using BamHI and XhoI. The generation of Kif18A-Nek2A (435–445) was performed by PCR, where the reverse primer contained the coding sequence for Nek2A 435–445. Kif18A Nek2A 370–445 was generated by subcloning Kif18A into pcDNA5/FRT/TO FLAG Venus Nek2A 370–445. Nek2A and fragments of Nek2A were generated by PCR and inserted into pcDNA5/FRT/TO FLAG Venus using BamHI and XhoI. The Nek2A sequence was made resistant to siRNA using the following primers: 5′-GAAACATCCAAACATTGTCAGATATTATGATCGGATTATTG-3′ and 5′-CAATAATCCGATCATAATATCTGACAATGTTTGGATGTTTC-3′ using pfu ultra polymerase (Stratagene). The generation of Nek2A mutants as well as 15 amino acids deletions was done using a quick-change protocol (Stratagene) using pcDNA5/FRT/TO FLAG Venus Nek2A siRES as a template. pET30a Nek2A was generated by PCR of Nek2A and insertion into the NcoI and NotI sites of the vector. pRSET A Nek2A 333–445 was obtained by subcloning from pcDNA5/FRT/TO FLAG Venus constructs using BamHI and XhoI. pET30 Cyclin B1 1–86 has been described previously (Garnett et al, 2009). All constructs were verified by complete sequencing of inserts.

The generation of stable HeLa and U2OS cell lines was undertaken in a similar manner to that described previously (Nilsson et al, 2008).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used at the indicated concentrations in PBS+5% milk unless otherwise stated: Nek2 (610594 BD Transduction Laboratories) 1:200 1% milk; Bub3 (611730 BD Transduction Laboratories) 1:1000; APC3 (610455, BD Transduction Laboratories) 1:1000; BubR1 (612503 BD Transduction Laboratories) 1:1000; Cyclin B (554176 BD Pharmingen) 1:2000; Mad2 (A300-301A Bethyl Laboratories) 1:2000; BubR1 (A300-995A Bethyl Laboratories) 1:500; APC7 (A302-551A Bethyl Laboratories) 1:2000; APC1 (A301-653A Bethyl Laboratories) 1:500 2% milk; Kif18A (A301-080A Bethyl Laboratories) 1:2000; FLAG (F3165 Sigma) 1:1000; Vinculin (V9131 Sigma) 1:40 000; FLAG (F7425 Sigma) 1:1000; APC8 (611401 Biolegend) 1:500 2.5% milk; Cdc20 (sc-13162 Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 1:1000; APC6 (sc6395 Santa Cruz) 1:200 1% milk; c-Myc (sc-40 Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Tubulin (ab6160 Abcam) 1:10 000; Aurora A (Ab1287 Abcam) 1:4000; Securin (ab94689 Abcam) 1:1000; GFP (11814460001 Roche) 1:200; APC10 (polyAb raised against full-length protein in J Pines laboratory) 1:500 1% milk; APC4 (mAb raised against C-terminal peptide J Pines laboratory); APC11 (mAb raised against C-terminal peptide J Pines laboratory). The BubR1 mAb antibody used for immunoprecipitation was raised against the TPR domain of BubR1.

Depletion of proteins by RNAi

All depletions of proteins by RNAi were performed using oligonucleotides at 100 nM and 2 μl/ml of Lipofectamine RNAi Max (Invitrogen) for 6 h. All oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma: Luciferase (5′-CGUACGCGGAAUACUUCGAA-3′), APC3 (5′-GGAAAUAGCCGAGAGGUAA-3′), APC10 (5′-GAAAUUGGGUCACAAGCUGUU), Cdc20 (5′-CGGAAGACCUGCCGUUACAUU-3′), Cdh1 (5′-UGAGAAGUCUCC-CAGUCAG-3′) and Nek2A (5′-AAACAUCGUUCGUUACUAU-3′). A mixture of two oligos were used for APC2, APC6 and APC8 knockdowns: APC2 oligonucleotide 1 (5′-GGUCUUACACAGGCUCAGU-3′), APC2 oligonucleotide 2 (5′-AGGCGGUGAUCUUGCUGUA-3′), APC6 oligonucleotide 1 (5′-CUAUGGACCUGCAUGGAUAUU-3′), APC6 oligonucleotide 2 (5′-CGAGGUAACAGUUGACAAAUU-3′), APC8 oligonucleotide 1 (5′-GAAAUUAAAUCCUCGGUAU-3′), APC8 oligonucleotide 2 (5′-GCAGUUGCCUAUCACAAUA-3′).

Purification and mass spectrometry of the APC/C

Nocodazole-arrested cells or cells released from nocodazole into 10 μM MG132 for 2 h were harvested by mitotic shake-off and washed with cold PBS buffer. The cells were resuspended in buffer A (175 mM NaCl, 30 mM Hepes-KOH pH=7.8, 6 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.05% Tween-20, 2 mM DTT, 3 mM ATP, 0.2 μM microcystin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml chymostatin and protease inhibitor cocktail; Complete tablets from Roche). Cells were lysed by nitrogen cavitation and lysate clarified by centrifugation. In all, 15–20 mg of total extract was incubated with 50 μl Protein G sepharose beads to which the APC4 antibody had been covalently coupled. Following incubation for 90 min, the beads were washed four times for 5 min with 750 μl buffer A without DTT and protease inhibitors. The APC/C complex was eluted with 50 μl buffer B (100 mM NaCl, 30 mM Hepes-KOH pH=7.8, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT and 1 mg/ml antigenic peptide) for 20 min and processed for mass spectrometry analysis.

Whole lanes were cut in 20 slices, destained completely and digested with trypsin (sequencing grade, Roche). Peptides were extracted with 0.25% formic acid-50% acetonitrile and dried in a Speed Vac (Thermo). Mass spectrometry analysis and data processing were carried out essentially as described previously (Pardo et al, 2010). Database searches were performed with Mascot v.2.1 (Matrix Science) against the human IPI database (v. June 2007). The search parameters were Trypsin/P with one missed cleavage, 20 p.p.m. mass tolerance for MS, 0.5 Da tolerance for MS/MS, variable modifications of Acetyl (Protein N-term), Carbamidomethyl (C), Deamidated (NQ), Gln->pyro-Glu (N-term Q), Glu->pyro-Glu (N-term E), Oxidation (M). Decoy database searches were performed at the same time as the real searches, resulting in false discovery rates under 5%. Protein identification required at least one high-confidence peptide (peptide score above identity threshold, e≤0.05, length >8 aas, precursor ion mass accuracy <5 p.p.m. where e≥0.005, peptide hit rank 1, delta peptide score >10).

Live-cell degradation assays

Cell lines were synchronized using a thymidine-aphidicolin scheme as described previously (Nilsson et al, 2008) and RNAi depletions of Nek2A performed after thymidine release. Microinjection of plasmids into HeLa cells has been described previously (Clute and Pines, 1999) and the stable cell lines were induced with 10 ng/ml doxycycline for 24 h before filming. Cells were filmed in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Life Technology) on a Deltavision Core microscope (Applied Precision) using a × 40 objective, NA=1.35 and the total fluorescence determined using the Image J software v 1.44 (NIH, Bethesda, USA).

Cdc20 and Cdh1 depletion experiments

HeLa cells were synchronized with a double thymidine block protocol and depletion of Cdc20 and Cdh1 was performed following release from the first thymidine block. Cells were released from the second thymidine block into 200 ng/ml nocodazole overnight and the mitotic harvested by shake-off.

For Cdh1 depletion experiments, cells were washed with pre-warmed DMEM and reseeded into dishes with fresh medium and all cells were collected at the indicated time points and lysed in RIPA buffer and protein concentration determined by BCA assay (Pierce).

For Cdc20 depletion experiments, cells were either seeded into DMSO or 10 μM RO-3306 (Merck-Calbiochem) and all cells harvested at the indicated times and lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

APC/C in vitro ubiquitination assays

APC/C ubiquitin ligase assays were carried out as previously described (Garnett et al, 2009) using APC/C captured with anti-APC4 antibodies cross-linked to protein G sepharose beads. Briefly, ubiquitination reactions were performed with ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, UbcH10, Ube2S, ATP, ubiquitin aldehyde and 35S-methionine-labelled substrates made with TnT T7 Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega).

Transient transfections

Cells were seeded at 90% density onto a 10-cm tissue culture dish. Plasmids (amounts are indicated in figure legends) were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 2.5 μl per ml of DMEM+FCS for 6 h before replacement of medium.

APC/C immunopurification assays

Cells were lysed in NETN (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM Tris pH 7.8 and 0.1% NP-40) supplemented with complete mini protease inhibitor (Roche) PhosStop (Roche) and 1 mM DTT for 20 min and clarified by centrifugation at 20 000 g. In general, purifications contained 10 μl of protein G sepharose cross-linked to 5 μg of antibody or 10 μl of GFP-Trap beads (Chromotek) in 200 μl of lysate (2.5 μg/μl). Unless otherwise stated, samples were incubated at 4°C on a thermomixer for 2 h at 1350, r.p.m., then washed in 3 × 500 μl of lysis buffer by inversion. Inputs contain 25 μg of lysate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jyoti S Choudhary for help with mass spectrometry. We are grateful to Andrew Fry and Prasad Jallepalli for discussions and Andrew Fry for the myc–Nek2A construct and Thomas U Mayer for providing Kif18A cDNA. We thank Stephen Taylor for providing the HeLa/FRT/TRex cell line and Jeffrey Parvin and Stephen Blacklow for providing the U2OS/FRT/TRex cell line. This work is supported by a grant to JN from the Lundbeck Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Council for Independent Research. The Proteomic Mass Spectrometry Laboratory was supported by the Wellcome Trust (079643/Z/06/Z).

Author contributions: APC/C purification and mass spectrometry analysis was designed by JP and performed by JN, LY and MP. Live-cell degradation assays and stability of Kif18A in Cdh1 and Cdc20 RNAi was performed by DH. Biochemical assays were performed by GS. BD performed immunofluorescence analysis and degradation of Kif18A fragments. JN performed the cloning and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Burton JL, Solomon MJ (2007) Mad3p, a pseudosubstrate inhibitor of APCCdc20 in the spindle assembly checkpoint. Genes Dev 21: 655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschhorn BA, Petzold G, Galova M, Dube P, Kraft C, Herzog F, Stark H, Peters J-M (2011) Substrate binding on the APC/C occurs between the coactivator Cdh1 and the processivity factor Doc1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 6–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CW, Enquist-Newman M, Morgan DO (2005) The APC subunit Doc1 promotes recognition of the substrate destruction box. Curr Biol 15: 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CW, Morgan DO (2002) The Doc1 subunit is a processivity factor for the anaphase-promoting complex. Nat Cell Biol 4: 880–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao WCH, Kulkarni K, Zhang Z, Kong EH, Barford D (2012) Structure of the mitotic checkpoint complex. Nature 484: 208–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clute P, Pines J (1999) Temporal and spatial control of cyclin B1 destruction in metaphase. Nat Cell Biol 1: 82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colland F, Jacq X, Trouplin V, Mougin C, Groizeleau C, Hamburger A, Meil A, Wojcik J, Legrain P, Gauthier J-M (2004) Functional proteomics mapping of a human signaling pathway. Genome Res 14: 1324–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croasdale R, Ivins FJ, Muskett F, Daviter T, Scott DJ, Hardy T, Smerdon SJ, Fry AM, Pfuhl M (2011) An undecided coiled coil: the leucine zipper of Nek2 kinase exhibits atypical conformational exchange dynamics. J Biol Chem 286: 27537–27547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca PCA, Kong EH, Zhang Z, Schreiber A, Williams MA, Morris EP, Barford D (2011) Structures of APC/C(Cdh1) with substrates identify Cdh1 and Apc10 as the D-box co-receptor. Nature 470: 274–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore B, Pines J (2010) How cyclin A destruction escapes the spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Biol 190: 501–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield C, Johnson VL, Tighe A, Ellston R, Haworth C, Johnson T, Mortlock A, Keen N, Taylor SS (2003) Aurora B couples chromosome alignment with anaphase by targeting BubR1, Mad2, and Cenp-E to kinetochores. J Cell Biol 161: 267–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, English CA, Ohi R (2010) The kinesin-8 Kif18A dampens microtubule plus-end dynamics. Curr Biol 20: 374–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzen den N, Pines J (2001) Cyclin A is destroyed in prometaphase and can delay chromosome alignment and anaphase. J Cell Biol 153: 121–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G (2002) Checkpoint protein BubR1 acts synergistically with Mad2 to inhibit anaphase-promoting complex. Mol Biol Cell 13: 755–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd S, Pines J, Lindon C (2008) APC/C Cdh1 targets aurora kinase to control reorganization of the mitotic spindle at anaphase. Curr Biol 18: 1649–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry AM, Arnaud L, Nigg EA (1999) Activity of the human centrosomal kinase, Nek2, depends on an unusual leucine zipper dimerization motif. J Biol Chem 274: 16304–16310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Higuera I, Manchado E, Dubus P, Cañamero M, Méndez J, Moreno S, Malumbres M (2008) Genomic stability and tumour suppression by the APC/C cofactor Cdh1. Nat Cell Biol 10: 802–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett MJ, Mansfeld J, Godwin C, Matsusaka T, Wu J, Russell P, Pines J, Venkitaraman AR (2009) UBE2S elongates ubiquitin chains on APC/C substrates to promote mitotic exit. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1363–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavet O, Pines J (2010) Progressive activation of CyclinB1-Cdk1 coordinates entry to mitosis. Dev Cell 18: 533–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagting A, Elzen Den N, Vodermaier HC, Waizenegger IC, Peters J-M, Pines J (2002) Human securin proteolysis is controlled by the spindle checkpoint and reveals when the APC/C switches from activation by Cdc20 to Cdh1. J Cell Biol 157: 1125–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hames RS, Wattam SL, Yamano H, Bacchieri R, Fry AM (2001) APC/C-mediated destruction of the centrosomal kinase Nek2A occurs in early mitosis and depends upon a cyclin A-type D-box. EMBO J 20: 7117–7127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick KG, Johnston RC, Smith DL, Murray AW (2000) MAD3 encodes a novel component of the spindle checkpoint which interacts with Bub3p, Cdc20p, and Mad2p. J Cell Biol 148: 871–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MJ, Kimata Y, Wattam SL, Lindon C, Mao G, Yamano H, Fry AM (2006) Early mitotic degradation of Nek2A depends on Cdc20-independent interaction with the APC/C. Nat Cell Biol 8: 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog F, Primorac I, Dube P, Lénárt P, Sander B, Mechtler K, Stark H, Peters J-M (2009) Structure of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome interacting with a mitotic checkpoint complex. Science 323: 1477–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa D, Pines J (2011) How APC/C-Cdc20 changes its substrate specificity in mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 13: 223–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Baxter JE, Fry AM, Yamano H (2008a) A role for the Fizzy/Cdc20 family of proteins in activation of the APC/C distinct from substrate recruitment. Mol Cell 32: 576–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Trickey M, Izawa D, Gannon J, Yamamoto M, Yamano H (2008b) A mutual inhibition between APC/C and its substrate Mes1 required for meiotic progression in fission yeast. Dev Cell 14: 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Vodermaier HC, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F, Peters J-M (2005) The WD40 propeller domain of Cdh1 functions as a destruction box receptor for APC/C substrates. Mol Cell 18: 543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer ER, Scheuringer N, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Peters JM (2000) Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Mol Biol Cell 11: 1555–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labit H, Fujimitsu K, Bayin NS, Takaki T, Gannon J, Yamano H (2012) Dephosphorylation of Cdc20 is required for its C-box-dependent activation of the APC/C. EMBO J 31: 3351–3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Gonzalez P, Scott MIF, Diez M, Sen O, Taylor SS (2011) BubR1 blocks substrate recruitment to the APC/C in a KEN-box-dependent manner. J Cell Sci 124(Part 24): 4332–4345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyskiela ME, Morgan DO (2009) Analysis of activator-binding sites on the APC/C supports a cooperative substrate-binding mechanism. Mol Cell 34: 68–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr MI, Hümmer S, Bormann J, Grüner T, Adio S, Woehlke G, Mayer TU (2007) The human kinesin Kif18A is a motile microtubule depolymerase essential for chromosome congression. Curr Biol 17: 488–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows JC, Shepperd LA, Vanoosthuyse V, Lancaster TC, Sochaj AM, Buttrick GJ, Hardwick KG, Millar JBA (2011) Spindle checkpoint silencing requires association of PP1 to both Spc7 and kinesin-8 motors. Dev Cell 20: 739–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow CJ, Tighe A, Johnson VL, Scott MIF, Ditchfield C, Taylor SS (2005) Bub1 and aurora B cooperate to maintain BubR1-mediated inhibition of APC/CCdc20. J Cell Sci 118: 3639–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Salmon ED (2007) The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 379–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J (2011) Cdc20 control of cell fate during prolonged mitotic arrest: do Cdc20 protein levels affect cell fate in response to antimitotic compounds? Bioessays 33: 903–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J, Yekezare M, Minshull J, Pines J (2008) The APC/C maintains the spindle assembly checkpoint by targeting Cdc20 for destruction. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1411–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Chen R-H (2004) Spindle checkpoint regulates Cdc20p stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 18: 1439–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo M, Lang B, Yu L, Prosser H, Bradley A, Babu MM, Choudhary J (2010) An expanded Oct4 interaction network: implications for stem cell biology, development, and disease. Cell Stem Cell 6: 382–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore LA, McCormack EA, Au SWN, Paul A, Willison KR, Harper JW, Barford D (2003) Doc1 mediates the activity of the anaphase-promoting complex by contributing to substrate recognition. EMBO J 22: 786–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J (2011) Cubism and the cell cycle: the many faces of the APC/C. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 427–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radnai L, Rapali P, Hódi Z, Süveges D, Molnár T, Kiss B, Bécsi B, Erdödi F, Buday L, Kardos J, Kovács M, Nyitray L (2010) Affinity, avidity, and kinetics of target sequence binding to LC8 dynein light chain isoforms. J Biol Chem 285: 38649–38657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber A, Stengel F, Zhang Z, Enchev RI, Kong EH, Morris EP, Robinson CV, da Fonseca PCA, Barford D (2011) Structural basis for the subunit assembly of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 470: 227–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudakin V, Chan GK, Yen TJ (2001) Checkpoint inhibition of the APC/C in HeLa cells is mediated by a complex of BUBR1, BUB3, CDC20, and MAD2. J Cell Biol 154: 925–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Bharadwaj R, Li B, Yu H (2001) Mad2-Independent inhibition of APCCdc20 by the mitotic checkpoint protein BubR1. Dev Cell 1: 227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton BR, Ng TM, Matyskiela ME, Carroll CW, Morgan DO, Toczyski DP (2006) An architectural map of the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev 20: 449–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev LT, Tovar C, Chen S, Knezevic D, Zhao X, Sun H, Heimbrook DC, Chen L (2006) Selective small-molecule inhibitor reveals critical mitotic functions of human CDK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10660–10665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodermaier HC, Gieffers C, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F, Peters J-M (2003) TPR subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex mediate binding to the activator protein CDH1. Curr Biol 13: 1459–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt KS, Vodermaier HC, Jacob U, Gieffers C, Gmachl M, Peters JM, Huber R, Sondermann P (2001) Crystal structure of the APC10/DOC1 subunit of the human anaphase-promoting complex. Nat Struct Biol 8: 784–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolthuis R, Clay-Farrace L, van Zon W, Yekezare M, Koop L, Ogink J, Medema R, Pines J (2008) Cdc20 and Cks direct the spindle checkpoint-independent destruction of cyclin A. Mol Cell 30: 290–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.