Summary

We reviewed the cranial nerve dysfunctions of eight patients with symptomatic cavernous internal carotid (CSIC) aneurysms treated by endovascular intraaneurysmal occlusion.

Aneurysms were classified into three types according to their location and direction of growth. Anterior type aneurysms`, which involved anterior bend of CSIC represented third nerve dysfunction. Posterior type aneurysms, which located posterior bend of CSIC preferred to affect sixth nerve function. CSIC aneurysms that extended over the both bends had total ophthalmoplegia. All patients responded to endovascular treatment, though partial resolution was recorded in the case of upward gaze or lateral gaze impairment. Endovascular treatment with detachable coils offers an excellent alternative with acceptable risks of morbidity.

Key words: symptomatic aneurysm, cavernous internal carotid artery, GDC

Introduction

Aneurysms involving the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery may produce cranial nerve dysfunction by compression, and occasionally rupture or ischemic events 1,2. The management of symptomatic cavernous aneurysms has evolved over a long period of time. Surgical attempts were parent vessel occlusion, carotid trapping and direct neck clipping with increasing technical experiences. These treatment choices could often carry long-term complications of stroke and high risk of mortality. Endovascular techniques have been developed and applied to this condition. Balloon occlusion test (BOT) with induced hypotension or blood flow evaluation reduced the risk of stroke. So recent treatment strategies are parent vessel occlusion in the case of adequate collateral supply or bypass surgery following sacrifice of IC. Despite these strategies, immediate and delayed stroke after carotid occlusion can still occur. We report the results of intraaneurysmal occlusion with detachable coils for the patients, who are not recommended for parent vessel occlusion. The neuro-ophthalmologic features of CSIC aneurysms are discussed in connection with the anatomy.

Methods

Patient population (table 1)

Table 1.

Clinical and aneurysm characteristics in eight patients

| Case | Age/Sex | Location | Size (mm) |

VER (%) |

Material | Follow-up (mos) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KR | 59/F | L | 30 | 2.5 | IDC | 90 | aldosteronism |

| KY | 74/F | R | 25 | 2.3 | IDC | 37 | BOTin, bilateral |

| OS | 66/F | L | 15 | 23 | GDC | 35 | BOTin |

| 25 | GDC | 12* | |||||

| OH | 77//F | L | 15 | 22 | GDC | 35 | BOTin |

| 33 | GDC | 28* | |||||

| HM | 25/F | L | 15 | 7 | GDC | 25 | bilateral |

| 12 | GDC | 21* | |||||

| UA | 49/F | L | 7 | 23 | GDC | 15 | |

| YH | 53/M | R | 20 | 18 | GDC | 8 | BOTin |

| BT | 68/F | L | 20 | 18 | GDC | 6 | ruptured |

|

VER = volume embolization ratio. BOTin = intolerance of balloon occlusion test * = months after the second embolization | |||||||

Eight patients with aneurysms that involved the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery were treated with detachable coils (IDC: two cases, GDC: six cases). These aneurysms originated entirely in the cavernous sinus. Carotid cave aneurysms were excluded from this study. Patient’s age at treatment rangedfrom 25 to 77 years, with an average of 59 years. This study included seven women and one man. Six aneurysms were located in the left cavernous sinus and two in the right. Four patients could not tolerate balloon test occlusion of the internal carotid artery. Another three patients were enrolled in this treatment due to primary aldosteronism, bilateral CSIC aneurysms, and a ruptured case. One patient chose endovascular embolization rather than parent vessel occlusion because of a small aneurysm. The angiographic size of the aneurysms ranged from 7 to 30 mm, with a mean of 18.4 mm. Two patients had thrombus demonstrated by magnetic resonance image. All patients presented with mass effect symptoms from compression of the adjacent cranial nerves by the aneurysms.

Endovascular treatments were performed from a transfemoral artery access in six patients and by carotid puncture in two. Double catheter technique was applied to one case and neck-remodeling technique was used in two.

Results

The CSIC aneurysms were classified into three types according to their location, especially relation to the internal carotid artery (IC). The types were assessed not only by angiogram and also by MRI, because of the high incidence of thrombus in the aneurysm.

Anterior type: aneurysms occupied anterior and middle compartments of the CS. They extended anterior to the anterior bend of the internal carotid, but not posterior to the posterior bend. Aneurysms compressed the C3-4 portion of IC medial and inferior (figures 1A,B).

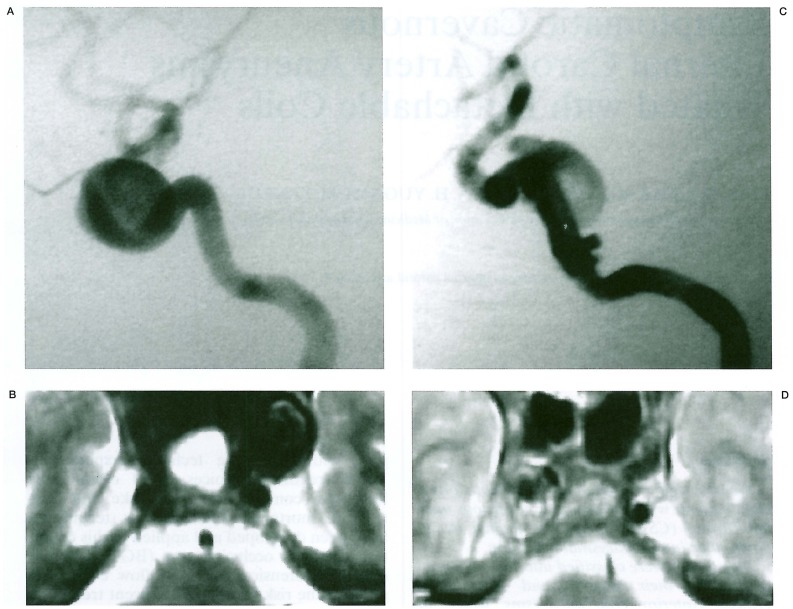

Figure 1.

Types of CSIC aneurysms. A,B) Anterior type (Case KR). Note internal carotid arteries are deviated anteriorly and inferiorly. C,D) Posterior type (Case HM). Aneurysms have the neck at the posterior carotid genu and occupy the posterior compartment of CS.

Posterior type: aneurysms occupied the posterior compartment of the CS. They expanded lateral and posterior, and compressed the posterior bend of IC anterior and medial (figures 1C,D).

Anterior-posterior type: aneurysms occupied the whole length of the CS. They expanded beyond the anterior and posterior bend of the IC (figure 2).

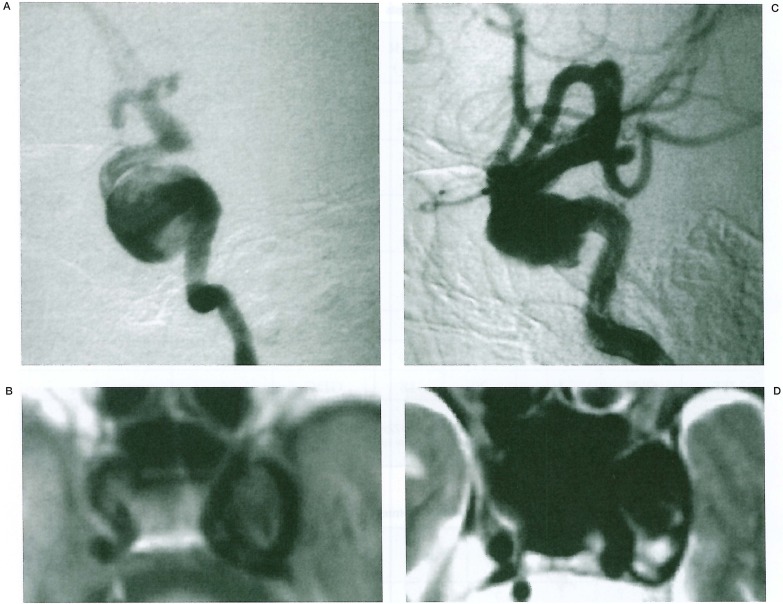

Figure 2.

CSIC aneurysms of antero-posterior type occupy the whole space of the cavernous sinus. Note the aneurysm expands beyond the anterior and also posterior bend of the IC (A,B)· MRI shows correct orientation of the aneurysm (C,D).

The clinical presentations depended on the location and the direction of growth. Anterior type aneurysms did not involve the abducens nerve. On the contrary, posterior type aneurysms rarely involve the oculomotor nerve. Anterior-posterior type showed total ophthalmoplegia (table 2). Nasal hemianopia was revealed in one patient. The aneurysm showed anterior type from the lateral view, although it mostly extended medial to the IC Trigeminal symptoms were unrelated to these types.

Table 2.

Response of symptoms following endovascular treatment with coils

| Case | Add | Up | Down | Palp | Pup | Abd | Tri | Dulation of symptoms |

Type of aneurysm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KR | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6M | A - M |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |||

| OS | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | A-M | |

| 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6M | ||

| 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |||

| HM | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 6M | P |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |||

| YH | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | IM | M-P |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | |||

| BT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4M | A _ M-P |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |||

| OH | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.5M | A _ M- P |

| 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | |||

| UA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1M | A *1 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |||

|

Add = adduction, Up = up ward gaze, Down down ward gaze, Palp = superior palpebre, Abd = abduction. Eye and eyelid movement is scored. 5; normal, 4; mild impairment, 3; moderate, 2; severe, and 1; complete dysfunction. Trigeminal symptoms(Tri) are classified as 3; no symptoms, 2; pain or numbness and 1; hypoesthesia. A; anterior bend, M; horizontal segment, P; posterior bend. *1; medial extension. | |||||||||

All cases achieved endovascular packing of the aneurysms with preservation of the parent artery. Two patients had low volume embolization rate (VER) because IDCs were used. Another six patients had 12 to 33% (mean = 21.5%) of VER, which was calculated from GDCs / aneurysm volume. Four patients showed coil compaction, and additional packing was done in three patients. No symptomatic ischemic event was recorded. Half of the patients had complete resolution of the presenting cranial nerve dysfunction. Dramatic, but partial improvement was recorded in the rest of the patients. Upward gaze disturbance remained in three of five patients with oculomotor palsy. Abducens palsy partially remained in three out of four patients after long-term follow-up. Angiographic coil compaction did not lead to a worsening of symptoms.

Discussion

Most cavernous aneurysms present with symptoms of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth cranial nerves. Medially projecting cavernous carotid aneurysm can produce optic nerve dysfunction. One patient in our series had subarachnoid bleeding due to extension into Meckel’s cave. A possible correlation between the size of aneurysms and the clinical presentation has been a mater of debate1. However, giant aneurysms may cause more symptoms than their smaller counterparts2. In this study location and direction of aneurysms revealed intimate relations with the cranial nerve symptoms. Anterior group presented oculomotor palsy and the posterior group tended to involve the abducens nerve. Upward gaze impairment was hard to cure after the treatment. The microsurgical anatomy of the cavernous sinus has been studied meticulously3. We will limit the anatomical consideration to the relationship between the carotid artery and oculomotor and abducens nerves. In the anterior compartment of the CS, the oculomotor nerve bifurcates into superior and inferior divisions, and then enters the superior orbital fissure. In this relatively small compartment, the third nerve travels adjacent to the anterior bend of the internal carotid artery. Anterior type aneurysms usually compress the IC medial and inferior, consequently the third nerve, especially its superior division may be harmed with ease. Guy et Al4 reported patients with oculomotor superior division palsy attributable to compression of the intracavernous aneurysm located by the anterior bend. On the contrary, the C5 (the posterior bend) portion of the IC occupies the posterior third compartment of the CS, where the oculomotor nerve just enters or runs out. On the other hand, the sixth nerve crosses the IC in this compartment. The sympathetic nerve arises from the superior cervical ganglion and joins the internal carotid artery. At the foramen lacerum, the sympathetic nerve sends filaments to the sixth nerve, which travels in the nerve and leaves to join the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve5. The sixth nerve is anchored by this anatomy. Posterior type aneurysms occupy the posterior third compartment of the CS. The origin and growth direction of the aneurysm may cause abducens palsy. Raeder described the paratrigeminal syndrome that consists of Horner’s syndrome and sixth nerve palsy6. Similar cases were reported with aneurysms of cavernous internal carotid artery. Isolated palsy of the abducens cranial nerve has been associated with lesions of posterior bend of the IC7,8.

The management of cavernous internal carotid aneurysms remains controversial. Proximal occlusion of the IC is preferred in the tolerable cases on BOT. However, the delayed stroke rate is between 6% and 7.5%. An extra haemodynamic stress on the collateral arteries also increases the chance of additional aneurysms developing. Intolerable cases need bypass surgery. Cavernous aneurysms that project into Meckel’s cave or superiorly through the carotid ring are at high risk for rupture. Direct surgical clipping of the aneurysm has also been reported with increasing experience. The reported complication rate was high, above 20%, which included 5% of deaths9. Large surgical series providing information on the responses of the patients with cranial nerve dysfunction documented the difficulty of achieving complete restoration of the function10. The current cases have demonstrated similar results with resolution of presenting cranial nerve signs. There was no ischemic event and no permanent morbidity or mortality associated with the current procedure11.

Conclusions

Patients who are represented with a symptomatic cavernous aneurysm and are not candidates for proximal occlusion can be treated with GDC. Presenting symptoms correlate with the location and expansive direction of the aneurysms. Cranial nerve dysfunctions generally respond to endovascular GDC treatment, but impairment of the sixth nerve and superior division of the third nerve makes it hard to obtain complete resolution. Aneurysm size and preoperative duration of symptoms may affect the likelihood of improvement. GDC treatment offers an alternative treatment choice without sacrificing the internal carotid artery.

References

- 1.Linskey ME, Sekhar LN, et al. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery; clinical presentation, radiographic features and pathogenesis. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn CD, Nicolle DA, et al. Giant cavernous aneurysms: Clinical presentation in fifty-seven cases. J Neuro-Opthalmol. 2000;20:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue T, Rhoton AL, Jr, et al. Surgical approach to the cavernous sinus: A microsurgical study. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:903–932. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guy JR, Day AL. Intracranial aneurysm with superior division paresis of the oculomotor nerve. Opthalmology. 1989;96:1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva MN, Saeki N, et al. Unusual cranial nerve palsy caused by cavernous sinus aneurysms. Clinical and anatomical considerations reviewed. Surg Neurol. 1999;52(2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raeder JD. Paratrigeminal paralysis of the oculopupillary symptomatic. Brain. 1924;47:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oleszczynska-Prost E, Tarantowicz-Mazurek D, et al. Abducent nerve palsy as the only symptom of intracavernous carotid aneurysm in a child. Klin Oczna. 1996;98(6):451–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal EZ, Gomori JM, et al. Recurrent abducens nerve palsy caused by dolichoectasia of the cavernous internal carotid artery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(2):255–257. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70799-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolenc V. Neurovascular surgery. New York: McGraw Hill; 1995. Intracavernous carotid artery aneurysms; p. 659.p. 672. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drake CG. Giant intracranial aneurysms: experience with surgical treatment in 174 patients. Clin Neurosurg. 1795;26:12–95. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/26.cn_suppl_1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halbach VV, Higashida RD, et al. Cavernous internal carotid aneurysms treated with electrolytically detachable coils. J Neuroophtalmol. 1997;17(4):231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]