Abstract

Under anaerobic environments, the mitochondria have undergone remarkable reduction and transformation into highly reduced structures, referred as mitochondrion-related organelles (MROs), which include mitosomes and hydrogenosomes. In agreement with the concept of reductive evolution, mitosomes of Entamoeba histolytica lack most of the components of the TOM (translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane) complex, which is required for the targeting and membrane translocation of preproteins into the canonical aerobic mitochondria. Here we showed, in E. histolytica mitosomes, the presence of a 600-kDa TOM complex composed of Tom40, a conserved pore-forming subunit, and Tom60, a novel lineage-specific receptor protein. Tom60, containing multiple tetratricopeptide repeats, is localized to the mitosomal outer membrane and the cytosol, and serves as a receptor of both mitosomal matrix and membrane preproteins. Our data indicate that Entamoeba has invented a novel lineage-specific shuttle receptor of the TOM complex as a consequence of adaptation to an anaerobic environment.

Mitochondria are highly divergent structures in eukaryotes, and often reveal degenerate morphology, function, and components in eukaryotes that have been adapted in anoxic or hypoxic environments. Such degenerated mitochondria with reduced or no organellar genome are called mitochondrion-related organelles (MROs), which include mitosomes and hydrogenosomes. While the minimal common function of MROs is still in debate1,2,3,4,5,6, protein import of nuclear-encoded proteins into MROs is indispensable for the organisms that possess MROs. All organisms possessing MRO that have been investigated so far, indeed retain at least a gene encoding the core translocation channel Tom40 of the TOM (Translocase of the Outer membrane of Mitochondria)7,8,9,10,11. However, in agreement with the concept of reductive evolution, other components of the canonical aerobic mitochondria such as subunits of TOM, SAM (Sorting and Assembly Machinery), TIM (Translocase of the Inner membrane of Mitochondria), and small TIM complexes8,12,13 are often missing in MROs. These data imply two possible scenarios of evolution of mitochondrial protein import: the majority of the import machinery of MROs has been secondarily lost7,8, or the transport machinery or subunits were replaced with unique and possibly lineage-specific components14.

The TOM complex is involved in the initial process of the import of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial preproteins into the mitochondria. Remarkable variation exists in the architecture of TOM complexes among eukaryotic lineages. In yeast and mammals, the translocation channel (Tom40), membrane-anchored receptors for the recognition of a targeting signal in preproteins (Tom22, Tom20, and Tom70), and accessory subunits (Tom5, Tom6, and Tom7) consist the TOM complex15,16. In plants, an 8-kDa truncated form of Tom22 serves as translocase17 and chloroplast import receptor Toc64 homolog functions as a TOM component18, while in trypanosomes, Tom40 appears to be replaced by Omp85 of archaic origin19. Tom20, a presequence binding receptor appeared to have independently evolved from two distinct ancestral genes in the animal and plant lineages20. Therefore, the investigation of the TOM complex may shed light on the evolution of the protein import machinery of endosymbiont-derived organelles.

Entamoeba histolytica is an anaerobic unicellular parasite, and causes hemorrhagic dysentery and extra intestinal abscesses that are responsible for an estimated 100,000 deaths in endemic areas annually21. This parasite possesses mitosomes, and is a good representative of mitochondrial diversification. Entamoeba MRO contains the sulfate activation pathway, which has been so far identified only in this organism9. Moreover, it lacks a genome22, has no membrane potential22,23, and is devoid of an import system using the canonical transit peptide9. Furthermore, E. histolytica has none of the homologous subunits of the TOM complex except Tom409,13. This fact, more specifically the lack of Tom20 and Tom70 receptors, suggests that import of mitosomal proteins does not depend on receptor recognition in Entamoeba, or that Entamoeba possesses an unprecedented receptor subunit undetectable by currently available in silico analysis. Here we show that the TOM complex in the E. histolytica mitosomes contains a lineage specific subunit, designated Tom60, which is associated with Tom40. Repression of Tom40 or Tom60 by gene silencing shows defects in protein import to mitosomes, and consequently retardation of proliferation. Tom60 is distributed to both the periphery of the mitosomal outer membrane and the cytosol. Moreover, our data strongly suggest that Tom60 is capable to bind in vitro to both mitosomal matrix proteins and membrane proteins.

Results

Demonstration of Tom40 localization on Entamoeba mitosomes

As we aimed to characterize TOM complex from Entamoeba, we first established an E. histolytica cell line expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged E. histolytica Tom40 (EhTom40) at the carboxyl terminus (Tom40-HA). To verify the expression and mitosomal localization of Tom40-HA, we fractionated lysates from Tom40-HA-expressing trophozoites by two rounds of Percoll gradient ultracentrifugation and analyzed the fractions by immunoblot with anti-HA antibody and anti-Cpn60 antiserum9. Cpn60 served as a canonical mitosomal marker. The banding pattern of Tom40-HA among fractions was similar to that of Cpn60 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Next, we carried out the immunofluorescence assay (IFA) using anti-HA antibody and anti-Cpn60 antiserum (Supplementary Fig. S2). Fluorescence signals of Tom40-HA were observed as dotted pattern and were merged with fluorescence signals of Cpn60, suggesting that EhTom40 is localized in mitosomes. Moreover, mitosomal localization of EhTom40 was also supported by immunoelectron microscopy (immuno-EM) (Supplementary Fig. S3) showing that Tom40-HA is concentrated on mitosomal outer membranes.

Identification of 600-kDa Entamoeba TOM complex and a novel subunit Tom60

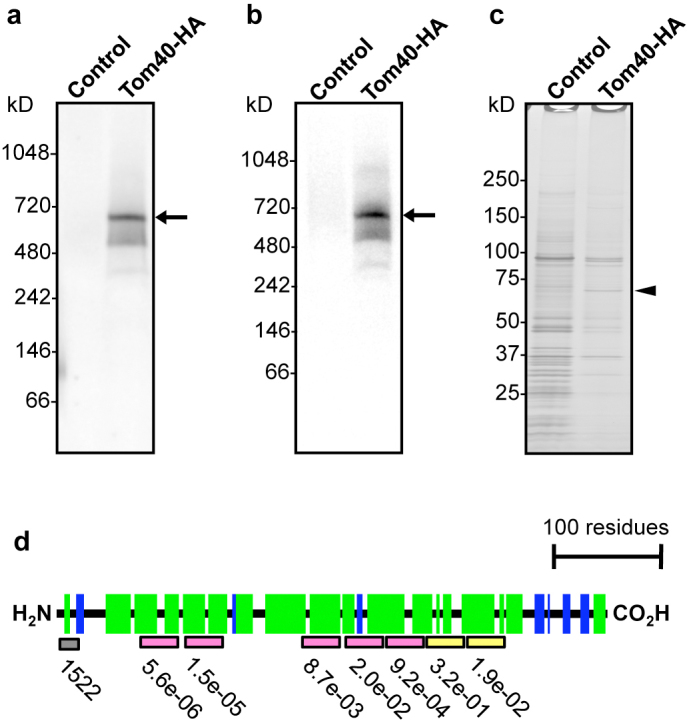

The TOM complex exists in yeast as a ~400-kDa complex, composed of Tom40, Tom22, Tom5, Tom6, and Tom724. To see if Entamoeba mitosomes contain TOM complex, and if so, to isolate the whole complex and identify proteins interacting with EhTom40, we investigated an EhTom40-containing complex by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) followed by immunoblot with anti-HA antibody. Immunoblot analysis of the 100,000 × g organelle-enriched fraction of Tom40-HA-expressing trophozoites with anti-HA antibody showed a 600-kDa band (Fig. 1a). To isolate and identify proteins that are associated with the 600-kDa band, the complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody (Fig. 1b) and electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. A band of approximately 60-kDa in size was detected exclusively in samples co-immunoprecipitated with lysates from the Tom40-HA-expressing trophozoites (Fig. 1c). The band was subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric analysis (LC-MS/MS), identified to be XP_657124 (Supplementary Fig. S4 and S5, and Supplementary Table S1A), and designated as E. histolytica Tom60 (EhTom60). EhTom60 was also detected by LC-MS/MS analysis of the 600-kDa complex (Supplementary Table S1B). The protein was previously identified in our mitosome proteome9.

Figure 1. Identification of the Entamoeba TOM complex and its novel subunit.

(a), The TOM complex demonstrated by BN-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. (b), Immunoprecipitation of the TOM complex (arrows) from Tom40-HA transformant by BN-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with anti-HA antibody. (c), SDS-PAGE and silver stain of immunoprecipitated TOM complex from Tom40-HA. Arrowhead indicates Tom60. (d), Prediction of the secondary structure and the domain organization of EhTom60. Gray box indicates the hydrophobic cluster, while pink and yellow boxes depict putative tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs) conserved among genus Entamoeba or those specific to E. histolytica, respectively. Probability and E-value are shown (Supplementary Fig. S4). Green and blue boxes indicate α-helices and β-strands, respectively, predicted by PSIPRED (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Lineage specific distribution of Tom60

Tom60 appears to be uniquely present in the genus. Tom60 orthologs were found in E. dispar and E. invadens (EDI_218540 and EIN_149090, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S4), whereas they were not identified in bacteria, archaea, and other eukaryotes. Among amoebozoan organisms, we confirmed by BLAST search (using the threshold of E-value < 0.1) that a Tom60 homolog is absent in the Dictyostelium discoideum (dictyBase: http://dictybase.org/) and Acanthamoeba catellani (https://www.hgsc.bcm.edu/content/acanthamoeba-castellani-neff) genomes, and the transcriptome of Mastigamoeba balamuthi (Spears, C. and Roger, A., personal communication).

In silico analyses indicate that Entamoeba Tom60 contains putative tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs)25 and an amino-terminal hydrophobic cluster (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S4). TPRs are implicated in protein-protein interactions, and are also present in Tom20 and Tom70, which are membrane-spanning receptors for mitochondrial import26, suggesting that Entamoeba Tom60 may be a receptor for mitosomal import. However, in contrast to the above-mentioned TPR-containing mitochondrial receptors, which consist of only α-helices, Entamoeba Tom60 appears to contain β-strands, based on the secondary structure prediction by PSIPRED (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S6). The predicted structural differences argue against the premise that Entamoeba Tom60 has a common evolutionary origin with Tom20 and Tom70.

Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses of TPR elements from 23 yeast proteins, plant Toc64, human Tom34 (Supplementary Table S2), 36 D. discoideum proteins (Supplementary Table S3), and 28 TPR-containing proteins from Entamoeba (Supplementary Table S4), showed that TPRs of Entamoeba Tom60s have no significant affinity with TPRs from other proteins. Therefore, we conclude that Entamoeba Tom60 is a genus-specific protein.

Localization and membrane topology of Tom60

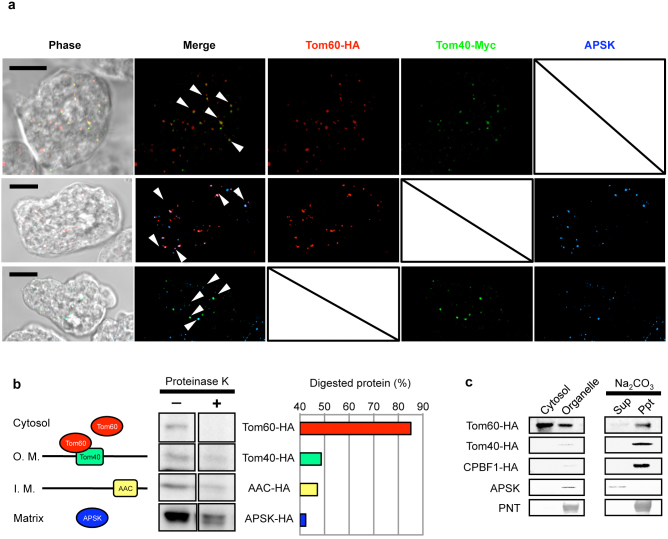

We confirmed by IFA the mitosomal localization of Tom60 in an E. histolytica cell line expressing Tom40-Myc and Tom60-HA. EhTom40, EhTom60, and APS kinase9 (APSK; XP_656278) were colocalized and concentrated in the mitosomes (Fig. 2a). However, faint cytosolic signals were also detected for EhTom60 (data not shown). Next, to verify localization, cellular fractionation of lysates was performed, followed by immunoblot analysis. EhTom60 was detected in both the 100,000 × g organelle fraction and the soluble supernatant fraction, suggesting that EhTom60 is present in both mitosomes and the cytosol. We next investigated the topology of EhTom60, EhTom40, and other mitosomal proteins by examining their sensitivity to proteinase K treatment followed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2b). Proteinase K sensitivity increased in the order of APSK-HA, AAC-HA (inner membrane protein23,27)/Tom40-HA, and Tom60-HA (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, sodium carbonate treatment, which liberates soluble and peripheral membrane proteins from organelles28, decreased the amount of organelle-associated Tom60-HA and increased that of soluble Tom60-HA, while Tom40-HA and CPBF1-HA (single-membrane spanning protein)29 remained in the pellet fraction after the treatment (Fig. 2b, left and Fig. 2c). These data demonstrate that EhTom60 is a cytosolic protein which can associate with EhTom40 on the surface of the mitosomal outer membrane.

Figure 2. Localization and topology of Tom40 and Tom60.

(a), Indirect fluorescence analyses of Tom40-HA and Tom60-Myc. Anti-APSK antiserum was used as mitosomal marker. Scale bar = 10 μm. (b), Differential sensitivity of several mitosomal proteins to proteinase K treatment. Left panel shows expected topologies of Tom60, Tom40, AAC, and APSK. “O. M.” and “I. M.” indicate outer and inner membranes, respectively. Middle panel shows immunoblots of each organelle fraction treated (+) or untreated (−) with proteinase K. Right panel shows the ratio of digested protein to that of total undigested protein. (c), Fractionation of mitosomal components. Lysates from amoebae expressing Tom60-HA, Tom40-HA, and CPBF1 (cysteine protease binding family protein 1; XP_65521829)-HA were fractionated. The three upper and two lower blots were reacted with anti-HA, anti-APSK, or anti-pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase (PNT, XP_00191409955) antibody. CPBF1 and PNT serve as a control for single- and multi-membrane spanning proteins, respectively.

Phenotypes of Tom40- and Tom60-gene silencing

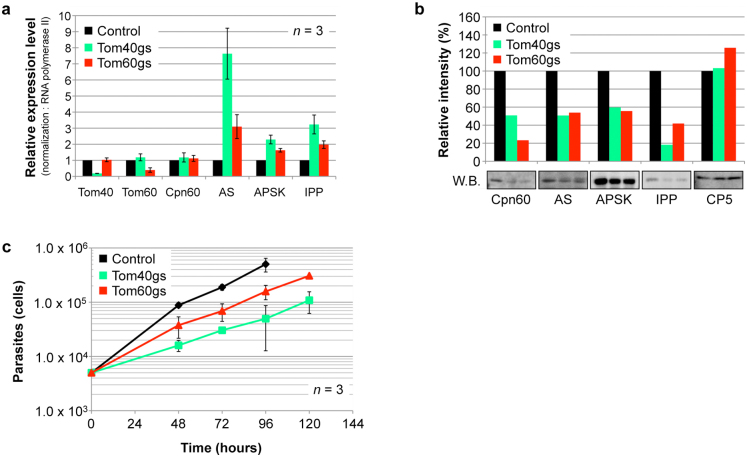

The importance of mitosomal matrix proteins, i.e., ATP sulfurylase (AS; XP_653570), APSK, inorganic pyrophosphatase (IPP; XP_649445), Cpn60, and AAC for E. histolytica proliferation was previously verified by gene silencing27. To demonstrate the biological importance of the mitosomal import machinery per se, we established E. histolytica strains in which EhTom40 and EhTom60 genes were silenced. Gene silencing was verified by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 3a). Repression of EhTom40 and EhTom60 genes caused a decrease in the transport of mitosomal matrix proteins, Cpn60, AS, APSK, and IPP (Fig. 3b). On the contrary, we observed a remarkable accumulation of AS, APSK, and IPP transcripts in EhTom40- and EhTom60-gene silenced strains (Fig. 3a). Finally, repression of EhTom40 and EhTom60 genes caused growth retardation when compared to control (Fig. 3c), suggesting that EhTom40 and EhTom60 are important for proliferation. These data also suggest that gene transcription of matrix proteins was upregulated by compensatory mechanisms, but was not sufficient to overcome undesirable effects caused by the repression of proteins involved in the mitosome import. Taken together, we conclude that EhTom40 and EhTom60 play essential roles in the import of matrix proteins to mitosomes.

Figure 3. Phenotypes of Tom40- and Tom60-gene silenced strain.

(a), Effects on the relative mRNA expression levels of mitosomal proteins of Tom40- and Tom60-gene silencing. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (b), Effects on the amount of mitosomal proteins in organelle fractions from Tom40-gene silenced (gs) and Tom60gs strains. Cysteine protease 5 (CP5) was used as loading control. Relative levels of each transcript and protein are shown after normalization against control. (c), Growth kinetics of Tom40gs, Tom60gs, and control strains.

Tom60 serves as a cytosolic receptor of mitosomal proteins

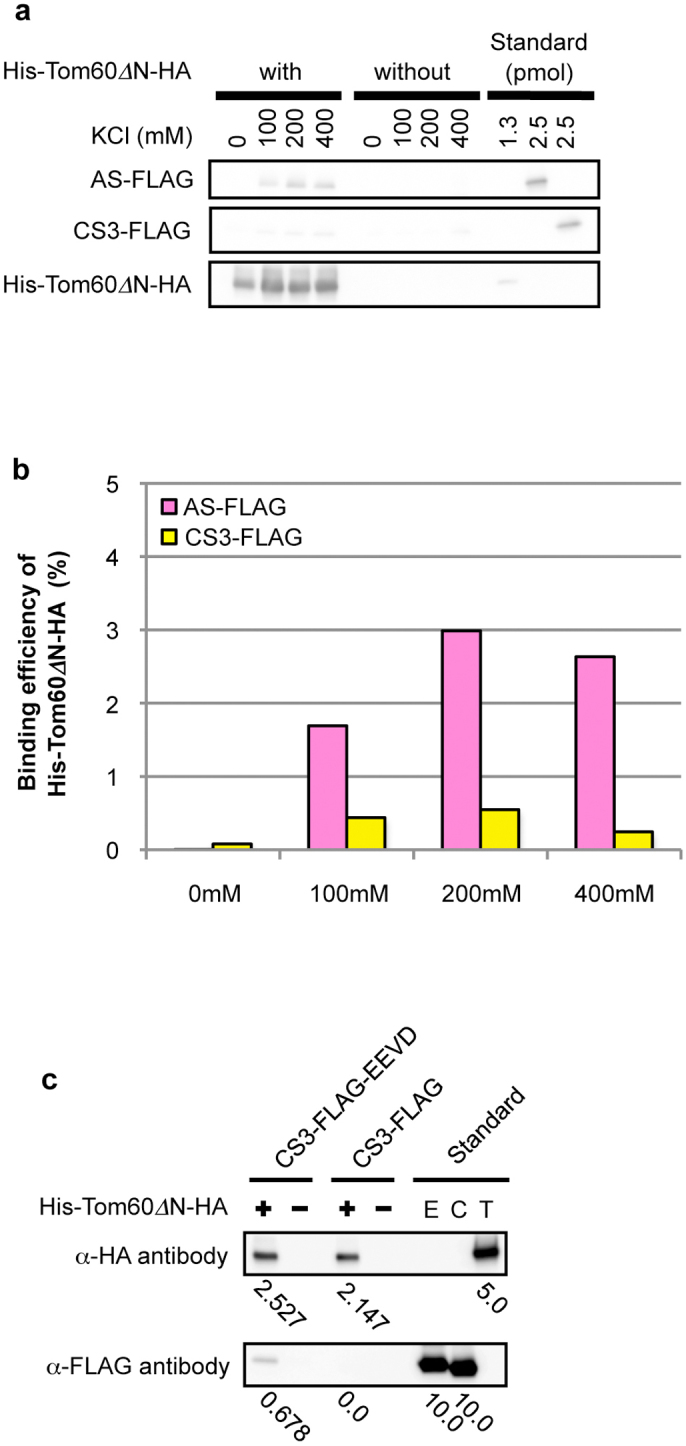

To verify whether EhTom60 functions as a receptor subunit of the TOM complex, we performed an in vitro binding assay, using recombinant AS and cysteine synthase isotype 3 (CS3, XP_653246; control for an irrelevant cytosolic protein) that have the FLAG-tag at the carboxyl terminus, and recombinant His-Tom60ΔN-HA, which lacks the amino-terminal hydrophobic region (a.a. 1–30) of EhTom60, and contained the His-tag at the amino terminus. We removed the amino-terminal region of EhTom60 because it negatively affected solubility of the recombinant protein. His-Tom60ΔN-HA showed a higher binding affinity towards AS-FLAG than CS3-FLAG (Fig. 4a and b; Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, the binding efficiency of His-Tom60ΔN-HA to AS-FLAG, but not CS3-FLAG, increased at higher KCl concentrations, which agreed well with the salt dependence of the binding between mitochondrial preproteins and the yeast Tom2030. These results strongly suggest that EhTom60 functions as a receptor for soluble proteins imported into the mitosomal matrix.

Figure 4. In vitro binding assay of Tom60 and a mitosomal protein.

(a), Immunoblotting of proteins bound to His-Tom60ΔN-HA. AS-FLAG is a mitosomal matrix protein, while CS3-FLAG is a cytosolic protein as a control. Approximately 40% of the whole eluates and 1.3 or 2.5% of standards used for the binding assay were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses with anti-HA and anti-FLAG mouse monoclonal antibody (clone M2, Sigma-Aldrich Japan). (b), Relative binding efficiency of His-Tom60ΔN-HA towards a mitosomal matrix protein. The data were quantitated based on the result shown in Fig. 4a. Vertical and horizontal axes indicate the binding efficiency of His-Tom60ΔN-HA towards substrates and the KCl concentrations, respectively. Low bars in the graph are described numerically while measurements and calculations are described in Supplementary Fig. S7 and Supplementary Methods. (c), The verification of interaction between His-Tom60ΔN-HA and the “EEVD” motif. CS3-FLAG-EEVD is an engineered cytosolic protein in which the “EEVD” motif was added to the carboxyl terminus, like in cytosolic Hsp70 and Hsp90, while CS3-FLAG is a negative control. Approximately 50% of the whole eluates and 5.0 or 10.0 pmol of standards used for the binding assay were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis, as described above. “E”, “C”, and “T” stand for CS3-FLAG-EEVD, CS3-FLAG, and His-Tom60ΔN-HA, respectively. Values below panels indicate protein amounts (pmol) estimated by densitometric scanning of the blots.

It has been demonstrated that in fungi, metazoa, and plants, mitochondrial transport of matrix and membrane proteins is mediated by different receptors, Tom20 and Tom70, respectively. Tom20 directly recognizes the amino-terminal presequence of soluble matrix proteins. However, Tom70 interacts with membrane preproteins directly, or indirectly via cytosolic heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and Hsp90 chaperones. In the latter case, Hsp70 and Hsp90 that are bound to mitochondrial membrane preproteins31 further bind to the TPR domains of Tom70 via their conserved tetrapeptide “EEVD” motif at the carboxyl terminus32. We thus tested if Entamoeba TPR-containing Tom60 can also recognize the tetrapeptide motif present in E. histoltyica Hsp70 and Hsp90. His-Tom60ΔN-HA was mixed with recombinant CS3-FLAG or its engineered form (CS3-FLAG-EEVD), which has the tetrapeptide motif at the carboxyl terminus. CS3-FLAG-EEVD, but not CS-FLAG, efficiently bound to His-Tom60ΔN-HA (Fig. 4c). These results indicate that the EhTom60 is involved in the mitosomal transport of membrane proteins via cytosolic Hsp70 and Hsp90.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that Entamoeba possesses Tom60, a novel genus-specific peripheral membrane component of the TOM complex, that functions as a receptor/carrier to transport mitosomal proteins from the cytoplasm to mitosomes. One of the striking features of Tom60 is its bipartite localization, which allows Tom60 to function as a carrier of de novo synthesized mitosomal preproteins in the cytoplasm and a structural component of the TOM complex on the mitosomal membrane. In this respect, Entamoeba Tom60 resembles a mammalian peripheral membrane protein, Tom34, which serves as a co-chaperone of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in a Tom70-dependent transport33. However, there is a clear difference between Entamoeba Tom60 and mammalian Tom34. Tom60 has direct physical interaction with TOM complex, whereas Tom34 is indirectly associated with Tom40 via Tom22 and Tom7033,34. Moreover, Entamoeba Tom60 appears to play an indispensable role, judged from the severe growth defect caused by gene silencing (knock down), similar to yeast Tom20 and Tom7035, whereas Tom34-deficient mice were viable, grew normally, and had a normal Mendelian inheritance pattern36. Thus, Entamoeba Tom60 represents an unprecedented essential bipartite-localized receptor/carrier for the protein import to MROs. It was presumed that Tom20 and Tom70 are loosely associated with other components of TOM complex, mobilized on the entire mitochondrial surface, and capable of interacting with preproteins37. Similarly, we assume that cytosolic localization of the Entamoeba Tom60 also maximizes the chance of its interaction with mitosomal preproteins. The mechanisms of the recruitment of Tom60 to the mitosomal outer membrane remain unsolved. One possibility is that Tom60 loaded with a precursor protein docks to the TOM complex, whereas free unloaded Tom60 remains dissociated from the TOM complex in the cytosol. Another possibility is the post-translational modifications. It has been recently reported that the binding of mammalian Tom20 and Tom70 toward preproteins is regulated by phosphorylation38.

Tom60 is a robust receptor for the mitosomal transport. Tom60 seems to transport both soluble and membrane mitosomal proteins. It has been shown in Opisthokonta that mitochondrial soluble matrix and membrane preproteins are transported via binding with distinct TPR-containing mitochondrial receptors, namely Tom20 and Tom70, which recognizes the amino-terminal transit peptide or the internal (cryptic) targeting signals, respectively31. Subsequently, these preproteins are passed from Tom20 and Tom70 to Tom22 and inserted into the Tom40 channel31. Therefore, Tom22 plays a role as a receptor for both mitochondrial soluble matrix and membrane preproteins. Similarly, Entamoeba Tom60 binds to a soluble mitosomal matrix protein, AS, as well as the “EEVD” motif, which is conserved in cytosolic Hsp70 and Hsp90 from three Entamoeba species. It was demonstrated that in mammals, cytosolic Hsp70 and Hsp90 are involved in the Tom70-dependent transport of mitochondrial membrane preproteins to TOM complex39. Among MRO-containing eukaryotes, no organism that possesses both Tom70 and Tom20 has been discovered. Encephalitozoon1 and Blastocystis40,41 encodes only a Tom70 homolog, suggesting that the Tom70 homolog may play a bifunctional role similar to Entamoeba Tom60. In contrast, in Giardia42, Trichomonas43, and Cryptosporidium44, no potential receptor component of TOM complex has been identified. These organisms most likely possess a lineage-specific receptor like Entamoeba Tom60. Further investigation is needed to clarify if such lineage-specific functional Tom60 homologs also contain the TPR domains for the cargo interaction.

It was hypothesized that the TOM complex in early eukaryotes is composed of Tom40, Tom22, and Tom717. It was also shown that the TOM complex of the aerobic free-living social amoebozoan D. discoideum consists of Tom40, Tom22, Tom7, and Tom6, and lacks Tom20 and Tom707,13. These data indicate that a common ancestor of amoebozoan species also contained Tom40, Tom22, and Tom7 in its TOM complex. This presumption is also supported by the existence of Tom40 homologs in the genome of other amoebozoan species including Polysphondylium45, and Acanthamoeba45, and the transcriptome of Mastigamoeba (Stairs, C. and Roger, A., personal communication), and Tom7 homologs in Polysphondylium (EFA78398) and Acanthamoeba (Contig6955 in the Acanthamoeba genome database). However, we did not detect Tom22 homologs in these amoebozoa. These data are consistent with the premise that Entamoeba probably secondarily has lost Tom22 during separation within Amoebozoa. A key question regarding a lineage-specific presence of Tom60 in Entamoeba is why and how the loss of the canonical subunit Tom22 and gain of Tom60 occurred. We presume that it is related to the lack of mitosomal targeting sequences in Entamoeba9. In the general model of mitochondrial matrix protein import, Tom22 interacts with the positive-charged surface in the amphiphilic α-helix of presequences30,46. In contrast, such ionic interaction does not appear to mediate the binding between Entamoeba Tom60 and mitosomal proteins. An alternative explanation of the loss of Tom22 is that in the Entamoeba ancestor the mitosomal proteins that were acquired by lateral gene transfer, such as sulfate activation enzymes, were poorly imported into mitosomes by Tom22.

Our current hypothesis as to how a novel TOM complex evolved in Entamoeba mitosomes is as follows: The Entamoeba ancestor was exposed to anaerobic environments, under which oxygen-dependent energy generation became unusable. Under these conditions, the mitochondrion lost its electron transport chain, membrane potential, and other aerobic mitochondrion-related functions. The loss of membrane potential across the inner membrane promoted an elimination of the canonical membrane potential-dependent TIM23 and TIM22 complexes31. In agreement with this hypothesis, membrane potential-dependent AAC, that is present in the aerobic mitochondria, became non-reliant on the membrane potential in E. histolytica23. Moreover, as described above, Entamoeba mitosomal proteins lack a canonical positively-charged transit peptide9, which is utilized for the electrophoretic import via the membrane potential31. Alterations of the TIM complex led to the rearrangement of the TOM complex, more specifically loss of Tom22, which is associated with the TIM23 complex in a typical aerobic mitochondrion. Finally, loss of Tom22 must have been compensated with the invention of a new targeting mechanism dependent on Tom60. It was also suggested that subunit replacement might have occurred in the TIM complex of Trichomonas vaginalis43 and Giardia intestinalis42. It is worth further investigating how commonly replacement of subunits occurred in anaerobic MRO-possessing eukaryotes.

Methods

Organisms

Trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica HM-1:IMSS cl647 and G348 strains were cultivated axenically in Diamond BI-S-33 medium49.

RNA and cDNA preparation

Total RNA was isolated from various strains by TRIZOL® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, San Diego, CA). mRNA was purified using GenElute™ mRNA Miniprep Kits (Sigma-Aldrich Japan). cDNA was synthesized from mRNA using SuperScript™ III RNase H- reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), oligo(dT)20 primer, and primer 1 (Supplementary Table S5).

Plasmid construction

E. histolytica Tom40 and Tom60 genes were PCR-amplified from cDNA using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and corresponding primer sets (Supplementary Table S5). After restriction digestion, amplified fragments were ligated into pEhEx/HA50 and pEhEx/Myc29 using Ligation-Convenience Kit (Nippongene, Tokyo, Japan). To generate the plasmid for Tom40-Myc/Tom60-HA double-expression, a fragment containing the Tom40-Myc protein coding region flanked by the upstream and downstream regions of the CS1 gene was PCR-amplified from pEhEx/Tom40-Myc by primers 6/7 (Supplementary Table S5), and inserted into the Spe I-digested pEhEx/Tom60-HA using In-Fusion® system (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). For gene silencing, a 400-bp fragment corresponding to the amino terminus of Tom40 and Tom60 was PCR-amplified with appropriate primers (Supplementary Table S5). Restriction-digested fragments were ligated into Stu I/Sac I double-digested psAP-2-Gunma plasmid27.

Amoeba transformation

Lipofection of trophozoites, selection, and maintenance of transformants were performed as previously described9.

Immunofluorescence assay

Preparation of organelle fraction

Amoeba strains that expressed HA-tagged Tom60-HA, Tom40-HA, AAC-HA, APSK-HA, and CPBF1-HA29 proteins, strains in which Tom40 and Tom60 genes were silenced, and mock transformants (pEhEx/HA and psAP2-Gunma) were washed three times with 2% glucose/PBS. After resuspension in lysis buffer (10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH7.2, 250 mM sucrose, protease inhibitors), cells were disrupted mechanically by a Dounce homogenizer. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min to separate the organelle and cytosolic fractions. The 100,000 × g organelle fractions were resuspended with lysis buffer, and were recollected by the centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min.

Immunoprecipitation of the TOM complex

Organelle fractions were solubilized with IP buffer (2% digitonin/50 mM BisTris-HCl, pH7.2/50 mM NaCl/10% [W/V] glycerol, protease inhibitors). The lysate was mixed with Protein G-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare), and Sepharose beads were removed by centrifugation. Precleared lysates were mixed with anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody conjugated with agarose (Sigma-Aldrich Japan) at 4°C for 3 h. Agarose was washed three times with IP buffer containing 1% digitonin. Bound protein was eluted by IP buffer containing 1% digitonin and 600 μg/ml HA peptide (Sigma-Aldrich Japan).

Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE)

Organelle fractions were solubilized by either 2% digitonin or n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) at 4°C for 30 min, and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. BN-PAGE was performed using NativePAGE™ Novex® Bis-Tris Gel System (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's protocol. Immunoprecipitated samples were mixed with 0.25% Coomassie® G-250 (Invitrogen) before electrophoresis.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric analysis

In-gel trypsin digestion of protein bands of interest and LC-MS/MS were performed as previously described52,53.

Proteinase K treatment

Organelle fractions (50 μg protein each) were treated with or without final 2.8 μg/ml proteinase K (Roche) at 4°C for 15 min, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody. Band intensities were evaluated using the Analysis Toolbox in ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare).

Na2CO3 treatment

Organelle fractions (1 mg protein) in lysis buffer were diluted 20 times with ice-cold 100 mM Na2CO3, pH 11.5 and 150 mM NaCl, kept at 4°C for 30 min, and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min. The 100,000 × g supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and the precipitate washed once with Na2CO3 solution. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described above. Anti-PNT (1:1,000) and anti-APSK (1:1,000) rabbit antisera were used as primary antibodies. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) was used as secondary antibody.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed as described27 using primer sets (primers 12-25; Supplementary Table S5) for Tom40, Tom60, Cpn60, AS, APSK, IPP, and Rnapol (XM_643999) genes.

Recombinant proteins

To generate recombinant histidine tagged (His6)-Tom60ΔN-HA, AS-FLAG, CS3-FLAG, and CS3-FLAG-EEVD proteins, we amplified Tom60, AS, and CS3 genes using appropriate primers sets (Supplementary Table S5) and pEhEx/Tom60-HA, pEhEx/AS-HA9, and pET15b/CS354 as templates. Fragments were digested by appropriate sets of restriction enzymes and ligated into pCold I (TaKaRa). These plasmids were transformed into BL21 Star™(DE3) One Shot® Chemically Competent E. coli (Invitrogen) and expression of recombinant proteins was induced by 1 mM IPTG. After lysis of bacteria and purification by Ni-NTA system (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany), the His6-tag was removed from His6-AS-FLAG, His6-CS-FLAG and His6-CS-FLAG-EEVD by AcTEV™ protease (Invitrogen).

In vitro binding assay of Tom60

The binding efficiency of His6-Tom60ΔN-HA was calculated and shown as the ratio of eluted AS-FLAG or CS3-FLAG to that of eluted His-Tom60ΔN-HA in the in vitro binding assay (Supplementary Methods). The hydrophobic nature of the amino terminus of Tom60 negatively affected solubility, thus it was removed prior to the binding assay. To verify the interaction between His6-Tom60ΔN-HA and the “EEVD” motif, we carried out the assay with CS3-FLAG-EEVD or CS3-FLAG. Assay condition was identical to in vitro binding assay as described in Supplementary Methods except that the assay buffer contained 50 mM KCl.

Author Contributions

T.M. did the experiments. T.M. and T.N. wrote the manuscript. T.M., F.M., K.N.-T. and T.N. interpreted the data.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Table S3

Supplementary Table S4

Acknowledgments

We thank Tsutomu Fujimura, Reiko Mineki, and Hikari Taka, the Division of Proteomics and Biomolecular Science, Biomedical Research Center at Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine for mass-spectrometric analysis, Courtney Spears and Andrew J. Roger, Centre for Comparative Genomics and Evolutionary Bioinformatics, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Dalhousie University for the information on Mastigamoeba transcriptome, Ghulam Jeelani and Eiko Nakasone for technical assistance, and Gil M. Penuliar and Herbert Santos for proof reading. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan to T.N. (23117001, 23117005, 23390099), a Grant-in-Aid on Bilateral Programs of Joint Research Projects and Seminars from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a Grant-in-Aid on Strategic International Research Cooperative Program from Japan Science and Technology Agency, a grant for research on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H23-Shinko-ippan-014) to T.N., a grant for research to promote the development of anti-AIDS pharmaceuticals from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation (KHA1101) to T.N., Strategic International Research Cooperative Program from Japan Science and Technology Agency to T.N. and by Global COE Program (Global COE for Human Metabolomic Systems Biology) from MEXT, Japan to T.N.

References

- Lill R. & Kispal G. Maturation of cellular Fe-S proteins: an essential function of mitochondria. Trends Biochem Sci. 8, 352–356 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maralikova B. et al. Bacterial-type oxygen detoxification and iron-sulfur cluster assembly in amoebal relict mitochondria. Cell Microbiol. 3, 331–342 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar J. et al. Mitochondrial remnant organelles of Giardia function in iron-sulphur protein maturation. Nature. 426, 172–176 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutak R. et al. Mitochondrial-type assembly of FeS centers in the hydrogenosomes of the amitochondriate eukaryote Trichomonas vaginalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 10368–10373 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A. V. et al. Localization and functionality of microsporidian iron-sulphur cluster assembly proteins. Nature. 452, 624–628 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaousis A. D. et al. Evolution of Fe/S cluster biogenesis in the anaerobic parasite Blastocystis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109, 10426–10431 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow T. & Schneider A. Evolution of macromolecular import pathways in mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 365, 799–817 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz E. & Lithgow T. Back to basics: A revealing secondary reduction of the mitochondrial protein import pathway in diverse intracellular parasites. Biochim Biophys Acta. In press (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi-ichi F., Yousuf M. A., Nakada-Tsukui K. & Nozaki T. Mitosomes in Entamoeba histolytica contain a sulfate activation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106, 21731–21736 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagley M. J. et al. The protein import channel in the outer mitosomal membrane of Giardia intestinalis. Mol Biol Evol. 9, 1941–1947 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall S. D. et al. Trichomonas vaginalis Hmp35, a putative pore-forming hydrogenosomal membrane protein, can form a complex in yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem 278, 30548–30561 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett A. M. & Johnson P. J. Mitochondrion-related organelles in eukaryotic protists. Annu Rev Microbiol. 64, 409–429 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal P. et al. The essentials of protein import in the degenerate mitochondrion of Entamoeba histolytica. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000812 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal P., Likic V., Tachezy J. & Lithgow T. Evolution of the molecular machines for protein import into mitochondria. Science. 313, 314–318 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad N. J., Ward L. A. & Ryan M. T. Import and assembly of proteins into mitochondria of mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1592, 97–105 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner N., Wiedemann N., Meisinger C. & Lithgow T. Assembling the mitochondrial outer membrane. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11, 1044–1048 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maćasev D. et al. Tom22', an 8-kDa trans-site receptor in plants and protozoans, is a conserved feature of the TOM complex that appeared early in the evolution of eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 8, 1557–1564 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew O. et al. A plant outer mitochondrial membrane protein with high amino acid sequence identity to a chloroplast protein import receptor. FEBS Lett. 557, 109–114 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusnik M. et al. Mitochondrial preprotein translocase of trypanosomatids has a bacterial origin. Curr Biol. 21, 1738–1743 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A. J., Hulett J. M., Likić V. A., Lithgow T. & Gooley P. R. Convergent evolution of receptors for protein import into mitochondria. Curr Biol. 16, 221–229 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S. L. Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 361, 1025–1034 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León-Avila G. & Tovar J. Mitosomes of Entamoeba histolytica are abundant mitochondrion-related remnant organelles that lack a detectable organellar genome. Microbiology. 150, 1245–1250 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. W. et al. A novel ADP/ATP transporter in the mitosome of the microaerophilic human parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Curr Biol. 15, 737–742 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Model K. et al. Multistep assembly of the protein import channel of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Nat Struct Biol. 8, 361–370 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpenahalli M. R., Lupas A. N. & Söding J. TPRpred: a tool for prediction of TPR-, PPR- and SEL1-like repeats from protein sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 8, 2. (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. J., Frazier A. E., Gulbis J. M. & Ryan M. T. Mitochondrial protein-import machinery: correlating structure with function. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 456–464 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi-ichi F. et al. Sulfate activation in mitosomes plays an important role in the proliferation of Entamoeba histolytica. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 5, e1263 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki Y. et al. Polypeptide and phospholipid composition of the membrane of rat liver peroxisomes: comparison with endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial membranes. J Cell Biol. 93, 103–110 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada-Tsukui K. et al. A novel class of cysteine protease receptors that mediate lysosomal transport. Cell Microbiol. 14, 1299–1317 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brix J., Dietmeier K. & Pfanner N. Differential recognition of preproteins by the purified cytosolic domains of the mitochondrial import receptors Tom20, Tom22, and Tom70. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20730–20735 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacinska A. et al. Importing mitochondrial proteins: machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 138, 628–644 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. C., Hoogenraad N. J. & Hartl F. U. Molecular chaperones Hsp90 and Hsp70 deliver preproteins to the mitochondrial import receptor Tom70. Cell. 112, 41–50 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faou P. & Hoogenraad N. J. Tom34: a cytosolic cochaperone of the Hsp90/Hsp70 protein complex involved in mitochondrial protein import. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1823, 348–357 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wilpe S. et al. Tom22 is a multifunctional organizer of the mitochondrial preprotein translocase. Nature. 401, 485–489 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczko M. et al. Deletion of the receptor MOM19 strongly impairs import of cleavable preproteins into Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 269, 9045–9051 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada K. et al. Expression of Tom34 splicing isoforms in mouse testis and knockout of Tom34 in mice. J Biochem. 133, 625–631 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker P. J. et al. Preprotein translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane: Molecular dissection and assembly of the general import pore complex. Mol Cell Biol. 18, 6515–6524 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O. et al. Regulation of mitochondrial protein import by cytosolic kinases. Cell. 144, 227–239 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. C., Hoogenraad N. J. & Hartl F. U. Molecular chaperones Hsp90 and Hsp70 deliver preproteins to the mitochondrial import receptor Tom70. Cell. 112, 41–50 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoeud F. et al. Genome sequence of the stramenopile Blastocystis, a human anaerobic parasite. Genome Biol. 12, R29 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaousis A. D. et al. A functional Tom70 in the human parasite Blastocystis sp.: implications for the evolution of the mitochondrial import apparatus. Mol Biol Evol. 28, 781–791 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedelský P. L. et al. The minimal proteome in the reduced mitochondrion of the parasitic protist Giardia intestinalis. PLoS One. 6, e17285 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada P. et al. The core components of organelle biogenesis and membrane transport in the hydrogenosomes of Trichomonas vaginalis. PLoS One. 6, e24428 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcock F. et al. A small Tim homohexamer in the relict mitochondrion of Cryptosporidium. Mol Biol Evol. 29, 113–122 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtkowska M. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial outer membrane β-barrel channels. Genome Biol Evol. 4, 110–125 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano K. et al. Tom20 and Tom22 share the common signal recognition pathway in mitochondrial protein import. J Biol Chem. 283, 3799–3807 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. S., Mattern C. F. & Bartgis I. L. Viruses of Entamoeba histolytica. I. Identification of transmissible virus-like agents. J Virol. 9, 326–341 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracha R., Nuchamowitz Y., Anbar M. & Mirelman D. Transcriptional silencing of multiple genes in trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica. PLoS Pathog. 2, e48 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. S., Harlow D. R. & Cunnick C. C. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other. Entamoeba. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 72, 431–432 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada-Tsukui K., Okada H., Mitra B. N. & Nozaki T. Phosphatidylinositol-phosphates mediate cytoskeletal reorganization during phagocytosis via a unique modular protein consisting of RhoGEF/DH and FYVE domains in the parasitic protozoon Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 11, 1471–1491 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada-Tsukui K., Saito-Nakano Y., Ali V. & Nozaki T. A Retromerlike Complex Is a Novel Rab7 Effector That Is Involved in the Transport of the Virulence Factor Cysteine Protease in the Enteric Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Mol Biol Cell. 16, 5294–5303 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineki R. et al. In situ alkylation with acrylamide for identification of cysteinyl residues in proteins during one- and two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2, 1672–1681 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makiuchi T. et al. Compartmentalization of a glycolytic enzyme in Diplonema, a non-kinetoplastid euglenozoan. Protist. 162, 482–489 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain A. et al. Metabolome Analysis Revealed Increase in S-Methylcysteine and Phosphatidylisopropanolamine Synthesis upon l-Cysteine Deprivation in the Anaerobic Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. J Biol Chem. 285, 39160–39170 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf M. A., Mi-ichi F., Nakada-Tsukui K. & Nozaki T. Localization and targeting of an unusual pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase in Entamoeba histolytica. Eukaryot Cell. 9, 926–933 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Table S3

Supplementary Table S4