Abstract

The present study was designed to determine the half-life of gfpm2+ mRNA, which encodes mycobacterial co-don-optimised highly fluorescent GFPm2+ protein, and to find out whether mycobacterial promoter activity can be quanti-tated more accurately using the mRNA levels of the reporter gene, gfpm2+, than the fluorescence intensity of the GFPm2+ protein. Quantitative PCR of gfpm2+ mRNA in the pulse-chased samples of the rifampicin-treated Mycobacterium smegmatis/gfpm2+ transformant showed the half-life of gfpm2+ mRNA to be 4.081 min. The levels of the gfpm2+ mRNA and the fluorescence intensity of the GFPm2+ protein, which were expressed by the promoters of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell division gene, ftsZ (MtftsZ), were determined using quantitative PCR and fluorescence spectrophotometry, respectively. The data revealed that quantification of mycobacterial promoter activity by determining the gfpm2+ mRNA levels is more accurate and statistically significant than the measurement of GFPm2+ fluorescence intensity, especially for weak promoters.

Keywords: gfpm2+, half-life, promoter activity, mycobacteria, quantitative PCR, fluorescence intensity.

INTRODUCTION

Drug-resistant strains of tubercle bacilli and opportunistic infection of HIV patients by tubercle bacilli have necessitated identification of novel drug targets that are vital to the bacilli. This has prompted the study of the regulation of expression of a large number of genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, in terms of cloned promoter activity in M. tuberculosis, and in the surrogate Mycobacterium smegmatis, a saprophyte used for the study of mycobacterial biology. The activity of the promoters is usually determined by quantifying the levels or activity of the reporter proteins, such as β-galactosidase (lacZ) [1, 2], chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (cat) [3], catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (xylE) [4], bacterial luciferase (luc) [5], and variants of green fluorescent protein (gfp) [6-9]. However, the levels and activity of these reporter proteins are dependent on the transcriptional, translational, and stability regulations, with the possibility of making measurements erroneous [10, 11]. Secondly, when promoter activity needs to be quantitated during prolonged durations and dormant conditions, GFP and LacZ, which are stable reporter proteins [12, 13], would persist throughout the duration of the experiment, making measurements erroneous. Although GFP proteins of short half-life are available [14], they are derivatives of GFPMUT2 of lower intensity, making detection and quantification of weak promoter activity difficult.

A direct measurement of the levels of the reporter gene mRNA would alleviate these concerns, provided the mRNA has short half-life. Further, a fluorescent reporter protein of very high intensity, and hence sensitivity, would facilitate initial qualitative noninvasive detection of promoter activity. In view of these facts, the present study was designed to determine: (i). the half-life of mRNA of the reporter gene, gfpm2+ [15], which encodes mycobacterial codon-optimised GFPm2+ protein of very high fluorescence intensity, and (ii). the accuracy and statistical reliability of the measurement of promoter activity by quantifying the levels of gfpm2+ mRNA, in comparison to the quantification of fluorescence intensity of GFPm2+ protein, in mycobacterial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155, which was used for the transformation with promoter constructs and transcription pulse chase experiments, was cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco) liquid medium containing 0.2% glycerol and 0.05% Tween-80, hygromycin (50 μg/ml) till OD600 nm 0.6 (mid-log phase). Escherichia coli JM109, which was used for the propagation of the plasmid constructs, was cultured in Luria-Bertani medium containing hygromycin (150 μg/ml) at 170 rpm at 37°C.

Plasmid Constructs

The E. coli-mycobacterial shuttle vector, pMN406 [8], contains gfpm2+ gene, which encodes the GFPm2+ variant possessing improved solubility characteristics, of high fluorescence intensity and twice more fluorescent than eGFP, and stable in expression in slow- and fast-growing mycobacteria [15]. It possesses its own ribosome binding site and was codon-optimised for optimal expression in mycobacteria. While pMN406-∆Pimyc-Q1-K1 carries the complete region encompassing five promoters (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P6) of MtftsZ, pMN406-∆Pimyc-K2-K1 carries only two promoters (P1 and P2) of MtftsZ [9]. pMN406 [8] carries the constitutive mycobacterial promoter, Pimyc, (positive control), which can be replaced with other promoters, and pMN406-∆Pimyc is devoid of promoter (negative control).

Rifampicin Treatment, RNA Extraction, and DNaseI Treatment

Mid-log phase M. smegmatis transformants containing pMN406 were grown to mid-log phase and treated with rifampicin (500 μg/ml), as described [16]. Cells were washed with 0.5% Tween-80 solution, and RNA isolation was carried out using hot-phenol method, as described [8], but with slight modifications. Cells were harvested at 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min post-addition of rifampicin and washed with 0.5% Tween-80 solution Cell pellets were transferred to 1.5 ml capacity microfuge tube and were repeatedly chilled in liquid nitrogen and crushed using micro pestle. Cells were lysed in 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 5 mM vanadyl ribonucleoside complexes (VRC). Lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min and then extracted with 65°C pre-heated phenol (saturated with 100 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.2, containing 10 mM EDTA), followed by once with phenol:chloroform (1:1, v/v), and twice with chloroform. Total RNA was precipitated using 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and an equal volume of isopropanol at -70°C for 3 hrs. RNA pellet was washed with 80% ethanol, dissolved in RNase-free water, and stored at -70°C. The RNA samples were quantitated using Nanospectrophotometer (Implen) and integrity was verified on 1% formaldehyde agarose gel. The gel was prepared in RNase-free buffer containing 20 mM sodium borate (pH 8.3), 0.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 3.3% formaldehyde. The electrophoresis was carried out in the same buffer with formaldehyde at 1.85%. The samples were loaded in the buffer containing 50% formamide (v/v), 6% formaldehyde, 20% glycerol (v/v), 20 mM sodium borate (pH 8.3), and 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), along with few grains of bromophenol blue. Five µg of total RNA preparations were treated with 5 units of DNase I (Fermentas), 2 µl of 10x DNase I buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 at 25°C, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM CaCl2), for 60 min followed by addition of 1 µl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and inactivation at 65°C for 10 min. RNA purity was confirmed with genomic DNA PCR using 500 ng RNA with gfpm2+-specific RT-PCR primers (mycgfp2+-RT-r and mycgfp2+-RT-f; Table 1) and M. smegmatis 16S rRNA-specific RT-PCR primers (Ms-16S-rRNA-RT-r and Ms-16S-rRNA-RT-f; Table 1). Integrity of the RNA was rechecked by loading 500 ng of DNase I-treated RNA on formaldehyde agarose gel.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Primers used in the Study

| mycgfp2-RT-f | 5' atgtcgaagggcgaggagctgttcaccggc 3’ |

| mycgfp2-RT-r | 5' gaagcactggacgccgtaggtcagggtggtg 3' |

| Ms-16SrRNA-RTf | 5' gcggtgtgtacaaggcccggg 3' |

| Ms-16SrRNA-RTr | 5' cgtcaagtcatcatgccccttatgtcc 3' |

cDNA Preparation

Three μg of total RNA was denatured in 1x reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3 at 25 °C, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM DTT) for 10 min at 65°C followed by snap-chilling on ice for 5 min. Respective primers (mycgfp2+-RT-r and mycgfp2+-RT-f; Table 1) were added and incubated for 5 min at a suitable annealing temperature for hybridisation. Snap chilling on ice for 5 min followed by extension of the primer using 40 units of Revert Aid Premium (RNase H-) reverse transcriptase (MBI Fermentas), 20 units of RiboLock (Fermentas), 2 µl of 10 mM dNTPs mix (Sigma) at 42°C for 1 hr (total reaction volume, 30 µl). Heat inactivation was carried out at 70°C for 10 min. One µl of cDNA preparation was taken as template for real time PCR. Similarly, the cDNA for the 16S rRNA was also prepared using specific primers (Ms-16S-rRNA-RT-r and Ms-16S-rRNA-RT-f; Table 1).

Real Time PCR

Real Time PCR was carried out using DyNamo SYBR Green qPCR kit (Finnzymes). The reaction mix contained 1x master mix, 1x of ROX dye, 0.5 µM each of forward and reverse primers, 1 µl of cDNA, and water to make up the reaction volume to 10 µl. Real Time PCR was performed for 40 cycles in ABI Prism (Real Time PCR System by Applied Biosystems) and the data were analysed using 7000 SDS (Version 2.3) software (Applied Biosystems). The Real Time PCR Cτ values for 16S rRNA, obtained using specific primers (Table 1), were used for normalisation of Cτ values for gfpm2+ mRNA.

Fluorescence Intensity Measurements

Fluorescence measurements were carried out in Fluoromax 4, HORIBA JOBIN YVON Fluorescence spectrophotometer, as described earlier [7]. In brief, different transformants were inoculated from glycerol stock and grown till O.D.600 = 0.6. These were again sub-cultured and grown to 0.6 O.D600 nm. In order to avoid clump formation, which is prevalent in mycobacterial cultures, 1 ml of culture was withdrawn and passed through a syringe containing 24 gauge needle. These cultures were then diluted 1:10 by adding 100 µl of culture in 900 µl of phosphate-buffered saline. GFP fluorescence was measured by using 490 nm excitation filter (slit width 10 nm) and 520 nm emission filter (slit width 10 nm). Fluorescence value of the buffer alone was deducted from the fluorescence values of GFPm2+ expression from the different constructs, and the deducted values were plotted.

Statistical Analysis

Fold activities of different promoter constructs were measured using fluorescence spectrophotometer and real time PCR from three independent biological triplicates. Promoter activities within a given method (i.e. fluorescence spectrophotometry or real time PCR) were compared and two-sided P-values were obtained by paired t-tests. To compare fluorescence intensity-based and real time PCR-based quantitation, unpaired t-tests were applied to obtain two-sided P-values.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Determination of gfpm2+ mRNA Half-life

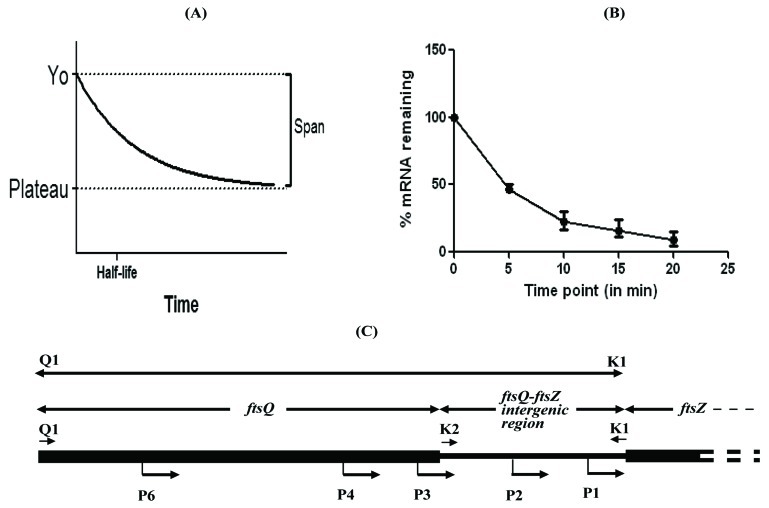

By plotting the levels of gfpm2+ mRNA remaining in the pulse-chased samples against time, the half-life of gfpm2+ mRNA was calculated, as first order exponential decay kinetics [18], as follows (Fig. 1A, B). Bacterial mRNA degradation follows first order exponential decay kinetics. Therefore, half-life of mRNA can be represented by the equation, t½ = 0.693/k, where k = the rate constant for mRNA decay (i.e., percent change over time). The value of k can be determined by plotting the concentration of mRNA over time and determining the slope of a best-fit line (slope = k). The value of rate constant, k for gfpm2+ mRNA degradation was found to be 0.1698. Thus, t½, the half-life was found to be 0.693/0.1698 = ~ 4.1 min. Rate constant was calculated using Graphpad Prism software using the following equation for one phase decay: Y = (Y0 - Plateau)*exp(-K*X) + Plateau, where X = Time, Y = mRNA levels, starting at Y0 and decaying (with one phase) down to plateau; Y0 and plateau have same units as Y; K = Rate constant equal to the reciprocal of the X-axis units (Fig. 1A, B).

Fig. (1).

The one phase decay curve (A) and the mRNA quantification curve (B) from the pulse-chase experiment. The half-life of gfpm2+ mRNA was calculated from the equation, t1/2= 0.693/k, where k= the rate constant for mRNA decay (i.e., percent change over time), as described in the text. (C). Organisation of the Q1-K1 region containing all the 5 promoters (P1,P2, P3, P4, and P6,) and of K2-K1 containing P1 and P2 promoters of MtftsZ.

Quantification of Promoter Activity

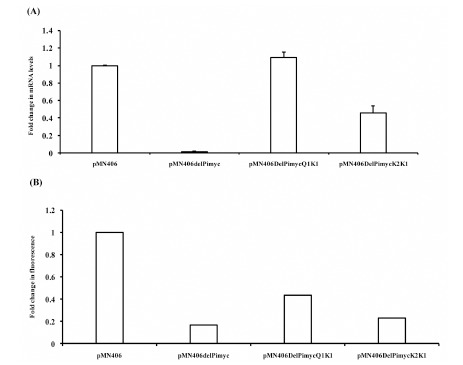

Subsequent to determining the half-life of gfpm2+ mRNA to be low, the promoters of the cytokinetic gene, ftsZ, of M. tuberculosis (MtftsZ), the activities of which were determined earlier in the laboratory [9], were used for quantitating promoter activity based on the gfpm2+ mRNA levels and GFPm2+ protein fluorescence intensity. The promoter region, Q1-K1, encompasses five promoters (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P6), while K2-K1 carries two promoters (P1 and P2), of MtftsZ [9] (Fig. 1C). These promoter regions were cloned in pMN406 [8], in place of the constitutive promoter, Pimyc, as described [9]. pMN406 and pMN406-∆Pimyc (devoid of Pimyc) were used as the positive control and negative control, respectively. The activity of Q1-K1, K2-K1, Pimyc, and of ∆Pimyc, were determined by quantitating the levels of gfpm2+ mRNA in the respective M. smegmatis mc2155 transformant, using real time PCR on gfpm2+ cDNA, as described [17]. With the gfpm2+ mRNA levels expressed from Pimyc (positive control) taken to be 1, the levels of gfpm2+ mRNA, from Q1-K1 was marginally (1.1-fold) higher (Fig. 2A). Whereas, the levels of gfpm2+ mRNA from K2-K1 region were 2.5-fold less than that of the positive control and 2.75-fold less than that from Q1-K1 (Fig. 2A). pMN406-∆Pimyc showed negligible expression. In parallel, the fluorescence intensity of GFPm2+ protein was determined in the M. smegmatis transformants, using fluorescence spectrophotometry, as described [7]. The fluorescence intensity of GFPm2+, expressed from Pimyc was 4.5 x 106 units (Fig. 2B), while that expressed from Q1-K1 accounted for 50% of the positive control. The level of expression from K2-K1 was 50% of the expression from Q1-K1 (Fig. 2B). ∆Pimyc showed basal level of fluorescence.

Fig. (2).

Quantification of the activity of the MtfsZ promoters using the levels of reporter mRNA and fluorescence intensity of the reporter protein. (A). Real time PCR quantification of the gfpm2+ reporter mRNA levels. (B). Fluorescence spectrophotometric quantification of the fluorescence intensity of the GFPm2+ reporter protein. Significant differences in the activity between the promoters under each method are indicated in term of P-values in the text.

Fold activities of different promoter constructs, which were measured using fluorescence spectrophotometer and real time PCR from three independent biological triplicates, were used for statistical analysis. Promoter activities within a given method (i.e. fluorescence spectrophotometry or real time PCR) were compared and two-sided P-values were obtained by paired t-tests. In order to compare fluorescence intensity-based and real time PCR-based quantification, unpaired t-tests were applied to obtain two-sided P-values. Statistical analysis of the promoter activities obtained from gfpm2+ mRNA quantification showed significant difference between K2K1 and ΔPimyc (P value = 0.0108) (Fig. 2A). On the contrary, GFPm2+ fluorescence from K2K1 showed no significant difference from the negative control, ΔPimyc (P value = 0.1759) (Fig. 2B). Similarly, GFPm2+ fluorescence from Q1K1 showed only 0.4-0.5 fold activity (P value = 0.001), in comparison to the positive control, Pimyc (Fig. 2B). On the contrary, qPCR showed that promoter activities of Q1K1 and Pimyc were comparable (Fig. 2A), as reported earlier [8]. Thus, for the determination of mycobacterial promoter activity, gfpm2+ mRNA quantification is accurate, statistically significant, and therefore reliable, as compared to GFPm2+ fluorescence intensity quantification, especially for regions of weak promoter activity, such as the K2-K1 region. The low half-life of gfpm2+ mRNA justifies the quantification of the mRNA levels for promoter activity.

Although the half-life of mRNA of GFPm [6] was 2.5 min [19], it was not used in this study as it gives lower fluorescence, compared to GFPm2+ [15], and hence not suited for quick qualitative detection of activity, especially of weak promoters. Similarly, the short half-life GFP variants [14] were not used, as they are derivatives of GFPMUT2, which is only 2-fold higher in fluorescence intensity than GFPMUT3 [20]. On the other hand, GFPm2+ has 10-fold higher fluorescence intensity than GFPMUT3 and double the fluorescence of eGFP, with improved solubility characteristics and stable expression in slow- and fast-growing mycobacteria [15]. Although lacZ mRNA half-life is only 90 sec [21], lacZ mRNA was not used for quantification, as GFPm2+ has the advantage of initial quick, non-invasive, and substrate-independent qualitative detection of promoter activity, over LacZ, using epifluorescence microscopy, fluorimetry, and flow cytometry [22], prior to the quantification of mRNA levels. Taken together, the present study offers a means for the sensitive, substrate-independent, quick, qualitative detection, and accurate and statistically significant quantification of mycobacterial promoter activity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a research grant (37(1361)/09/EMR-II) from CSIR and by Centre of Excellence in Tuberculosis Research part-grant from DBT. SM was a CSIR Senior Research Fellow. The infrastructural support from the DBT to the Indian Institute of Science, and from UGC-CAS, and DST-FIST to the Microbiology and Cell Biology Department, are acknowledged. The authors declare that they do not have any competing or conflicting interests.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Timm J, Lim EM, Gicquel B. Escherichia coli-Mycobacteria shuttle vectors for operon and gene fusions to lacZ: the pJEM series. J Bacteriol. 1994; 176:6749–53. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6749-6753.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland B, Purkayastha A, Monserrat C, Casart Y, Takiff H, McDonough KA. Fluorescence-based detection of lacZ reporter gene expression in intact and viable bacteria including Mycobacterium species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999; 179:317–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DasGupta SK, Bashyam MD, Tyagi AK. Cloning and assessment of mycobacterial promoters by using a plasmid shuttle vector. J Bacteriol. 1993; 175:5186–92. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5186-5192.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curcic R, Dhandayuthapani S, Deretic V. Gene expression in mycobacteria: transcriptional fusions based on xylE and analysis of the promoter region of the response regulator mtrA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1994; 13:1057–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts EA, Clark A, Friedman RL. Bacterial luciferase is naturally destabilised in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and can be used to monitor changes in gene expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005; 243:243–49. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker LP, Brooks DM, Small PL. The identification of Mycobacterium marinum genes differentially expressed in macrophage phagosomes using promoter fusions to green fluorescent protein. Mol Microbiol. 1998; 29:1167–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowley SC, Av-Gay Y. Monitoring promoter activity and protein localisation in Mycobacterium spp. using green fluorescent protein. Gene. 2001; 264:225–31. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy S, Mir MA, Anand SP, Niederweis M, Ajitkumar P. Identification and semi-quantitative analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv ftsZ gene-specific promoter activity-containing regions. Res Microbiol. 2004; 155:817–26. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy S, Ajitkumar P. Transcriptional analysis of the principal cell division gene, ftsZ, of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2005; 187:2540–50. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2540-2550.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pessi G, Blumer C, Haas D. lacZ fusions report gene expression, don't they? Microbiology. 2001; 147:1993–95. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner JB, Lolkema JS. LacZ-promoter fusions: the effect of growth. Microbiology. 2002; 148:1241–3. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-5-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tombolini R, Unge A, Davey ME, de Bruijn FJ, Jansson JK. Flow cytometric and microscopic analysis of GFP-tagged Pseudomonas fluorescens bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997; 22:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll P, James J. Assaying promoter activity using LacZ and GFP as reporters. Methods Mol Biol. 2009; 465:265–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-207-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blokpoel MC, O'Toole R, Smeulders MJ, Williams HD. Development and application of unstable GFP variants to kinetic studies of mycobacterial gene expression. J Microbiol Methods. 2003; 54:203–11. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinhauer K, Eschenbacher I, Radischat N, Detsch C, Niederweis M, Goroncy-Bermes P. Rapid evaluation of the mycobactericidal efficacy of disinfectants in the quantitative carrier test EN 14563 by using fluorescent Mycobacterium terrae. Appl Env Microbiol. 2010; 76:546–54. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01660-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sala C, Forti F, Magnoni F, Ghisotti D. The katG mRNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis is processed at its 5' end and is stabilised by both a polypurine sequence and translation initiation. BMC Microbiol. 2008;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arumugam M, Anand D, Vijayarangan N, et al. Nucleoside di-phosphate kinase gene is expressed through multiple transcripts in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Open J Microbiol. 2012;4:197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaern M, Elston TC, Blake WJ, Collins JJ. Stochasticity in gene expression: From theories to phenotypes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:451–64. doi: 10.1038/nrg1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andini N, Nash KA. Expression of tmRNA in mycobacteria is increased by antimicrobial agents that target the ribosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;322:172–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimised mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bannantine JP, Barletta RG, Thoen CO, Andrews RE., Jr Identification of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis gene expression signals. Microbiology. 1997;143:921–8. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Errampalli D, Leung K, Cassidy MB, et al. Applications of the green fluorescent protein as a molecular marker in environmental microorganisms. J Microbiol Meth. 1999;35:187–99. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]