Abstract

Background:

Recent reports from cancer screening trials in high-risk populations suggest that autoantibodies can be detected before clinical diagnosis. However, there is minimal data on the role of autoantibody signatures in cancer screening in the general population.

Methods:

Informative p53 peptides were identified in sera from patients with colorectal cancer using an autoantibody microarray with 15-mer overlapping peptides covering the complete p53 sequence. The selected peptides were evaluated in a blinded case–control study using stored serum from the multimodal arm of the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening where women gave annual blood samples. Cases were postmenopausal women who developed colorectal cancer following recruitment, with 2 or more serum samples preceding diagnosis. Controls were age-matched women with no history of cancer.

Results:

The 50 640 women randomised to the multimodal group were followed up for a median of 6.8 (inter-quartile range 5.9–8.4) years. Colorectal cancer notification was received in 101 women with serial samples of whom 97 (297 samples) had given consent for secondary studies. They were matched 1 : 1 with 97 controls (296 serial samples). The four most informative peptides identified 25.8% of colorectal cancer patients with a specificity of 95%. The median lead time was 1.4 (range 0.12–3.8) years before clinical diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest that in the general population, autoantibody signatures are detectable during preclinical disease and may be of value in cancer screening. In colorectal cancer screening in particular, where the current need is to improve compliance, it suggests that p53 autoantibodies may contribute towards risk stratification.

Keywords: p53, microarray, biomarkers, autoantibodies, rectum, colon

Cancer screening is a core part of any national cancer control plan. Most current screening tests involve a single marker. It is likely that in the future, screening will be based on serial change and in the case of a blood test involve a panel of proteins arrayed on a diagnostic chip (Jacobs and Menon, 2011). Possible candidates for the latter include autoantibody signatures that take advantage of antitumor immunity to magnify the immune response to tumour antigens. Recent reports from cancer screening in high-risk populations, such as smokers, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asbestosis has shown that autoantibodies are detectable before radiographic detection in 26.5% of lung cancer patients (Trivers et al, 1996; Soussi, 2000; Li et al, 2005; Zhong et al, 2006; Qiu et al, 2008). There are however few data on such signatures in the general population and their role in early detection of cancer.

A likely candidate in such a diagnostic panel is p53, inactivation of which is a common event that occurs early in cancer development in many malignancies. Serum p53 autoantibodies are reported in many cancer patients and there is growing interest in their role in early detection of cancers (Soussi, 2000). Cancer-selective mutations cause overexpression, conformational stabilisation, nuclear accumulation and increase in circulatory half-life of mutated p53 (Winter et al, 1992; Casey et al, 1996), and result in induction of antibodies to several different immunodominant areas in p53 (Schlichtholz et al, 1992; Labrecque et al, 1993).

It is common for the initial reported performance of early detection markers not to be validated in independent data sets (Jacobs and Menon, 2011). It is likely that systematic bias in the selection of both cases and controls has a significant role. Hence, it has been suggested that biomarker study design should involve blinded evaluation in nested case–control studies within clinically relevant prospective cohort studies, where specimens have been banked before outcome ascertainment (Pepe et al, 2008). In keeping with this, we have evaluated the potential of p53 autoantibody signature in serial serum samples banked before colorectal cancer diagnosis in the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). We chose colorectal cancer as the exemplar, as it is one of the common cancers and contributes to a significant proportion of cancer-related death in the western world (GLOBOCAN; http://globocan.iarc.fr/). A blinded evaluation of informative p53-peptide epitopes was undertaken using an approach similar to the microarray strategy we recently developed to detect cancer-associated autoantibodies (Pedersen et al, 2011).

Materials and Methods

Samples

Sample set used to identify informative peptides

Two sets of sera, time of diagnosis sample set 1 and 2 from patients with colorectal cancer and controls were obtained from Asterand, Inc., Detroit, MI, USA. All cancer sera from Asterand, Inc., were taken before any cancer treatment, including surgery. Sample set 1 consisted of 58 cases (male, n=33, female, n=25) and 53 controls (male, n=33, female, n=20). Sample set 2 consisted of 157 cases (male, n=86, female, n=71) and 40 controls (male, n=20, female, n=20). Controls were sex-matched healthy volunteers.

Sample set from the UKCTOCS

Sample set from the UKCTOCS: Serum samples were obtained from women participating in the UKCTOCS (Menon et al, 2008, 2009). In the UKCTOCS trial (Menon et al, 2008), 202 638 postmenopausal women aged 50–74 years were recruited in 2001–2005, following random invitation from the population register. Exclusion criteria included bilateral oophorectomy, active malignancy, previous ovarian cancer and increased risk of familial ovarian cancer. They were randomised to the multimodal (annual screening using serum CA125, n=50 640), ultrasound (annual screening with ultrasound, n=50 639) or control group (n=101 359). At recruitment, written consent was obtained for use of data and samples in future secondary studies. Approval for use in this study was obtained from the Joint UCL/UCLH Committees on the Ethics of Human Research (Committee A) (Amendment 4, 31 June 2009). All participants are followed through a ‘flagging study’ with the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care in England and Wales and via the Central Services Agency and Cancer Registry in Northern Ireland. This provides notification of cancer registrations or deaths in the cohort. Up-to-date cancer registration data was obtained from the agencies in December 2009. Cancer notification in the controls was re-checked on 16 February 2011, to confirm that none of the controls had developed a cancer while the study was underway. The cases were women in the multimodal group of the UKCTOCS with more than one serum sample who were diagnosed with malignant neoplasm of colon, rectosigmoid junction or rectum (ICD-10 codes C18, C19, C20) up to 3 September 2009 after randomisation to the trial. Controls were women from the same centre who had no history of any cancer at last follow-up (16 February 2011) and had donated serum samples in the same year as the case. Controls were matched to cases using age (within 5 years) at the last sample before diagnosis in a 1 : 1 ratio. For baseline characteristics, (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the UKCTOCS colorectal cancer cases and controls.

|

Median (25th–75th centiles)

|

P -value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | Controls ( n =94) | Cancers ( n =97) | Mann–Whitney test |

| Age (years) at randomisation | 65.0 (60.2–69.7) | 65.0 (61.3–70.4) | 0.606 |

| Age at last period | 50.6 (47.4–53.7) | 49.9 (45.6–52.9) | 0.389 |

| Duration of HRT use in those on HRT at randomisation (years) | 12.1 (8.4–17.5) | 12.6 (10.3–14.6) | 1 |

| Duration of OCP use (years) in those who had used it | 6 (2–15) | 5 (2–13.5) | 0.967 |

| Miscarriages (pregnancies <6 months) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.954 |

| No. of children (pregnancies >6 months) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.083 |

| Height (cms) | 162.6 (157.5–167.6) | 160.0 (156.2–165.1) | 0.167 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.0 (62.1–76.2) | 66.7 (60.0–76.2) | 0.379 |

|

Number (%)

|

Fisher’s exact test | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.285 | ||

| White | 89 (94.7%) | 93 (95.9%) | |

| Black | 4 (4.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Other | 0 | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Hysterectomy | 12 (12.8%) | 13 (13.4%) | 1 |

| Ever use of OCP | 39(41.5%) | 46 (47.4%) | 0.467 |

| Use of HRT at recruitment | 12 (12.8%) | 25 (25.7%) | 0.028 |

| Maternal history of ovarian cancer | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (2.1%) | 1 |

| Maternal history of breast cancer | 6 (6.4%) | 5 (5.2%) | 0.765 |

Abbreviations: HRT=hormone replacement therapy; OCP=oral contraceptive pill.

At all 13 trial centres, blood samples were collected into Greiner Bio-One gel tubes (Greiner Bio-One Ltd., Stonehouse, Cat. no.: 455071) and shipped overnight to the central laboratory. The blood was centrifuged at 4000 r.p.m. for 10 min and 500 μl aliquots of serum dispensed into straws (MAPI CryoBioSystem, Cryo Bio System, Paris, France) that were heat sealed, barcoded, databased and frozen using a two-stage process; 24 h at −80°C and then in liquid nitrogen (vapour phase at −180°C). For this study, samples were thawed and immediately aliquoted into 2D barcoded tubes (0.5 ml Tracker Tubes in Loborack, MP52325, Micronics, High Wycombe, UK), refrozen at −80°C and shipped frozen to the University of Copenhagen where they were assayed blinded to the case–control status.

p53 peptide microarray

15-mer peptides with 10-amino-acid overlap representing the whole p53 protein (Supplementary data 1) were printed on Schott Nexterion Slide H (Schott AG, Mainz, Germany) as described (Pedersen et al, 2011). In brief, peptides were printed on a BioRobotics MicroGrid II spotter (Genomics Solution, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) using Stealth 3B Micro Spotting Pins (Telechem International ArrayIt Division, Arrayit Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Human sera, diluted 1 : 25 (1 μl in 25 μl PBS with 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) for MPX16 and 1 : 4 for MPX48 (1 μl in 4 μl PBS-T), were incubated on the slides in a closed container at room temperature with gentle agitation for 1 h, washed three times in PBS-T, followed by 1 h incubation with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fc specific) diluted 1 : 5000 in PBS-T. Slides were washed and scanned in a ProScanArray HT Microarray Scanner (PerkinElmer) followed by image analysis with ProScanArray Express 4.0 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Each spot was done in three or four replicates and the mean value of relative fluorescence intensity was used. For comparison, slides were scanned with identical scanning parameters. Data were analysed and plotted using Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The intra-assay variation of spot triplicates was less than 10%. Coefficient of variation values of the inter-assay variations were between 17% and 26% for peptides with relative fluorescence intensity values in the dynamic range between 25 000 and 40 000. Peptides with relative fluorescence intensity values above 50 000 had coefficient of variation values 2–5%.

The UKCTOCS samples were randomised, coded and blinded for the investigators performing the microarray analysis. The code was revealed after the complete data set was completed and quantified.

p53 protein ELISA assay

The last serial sample obtained from each individual in the UKCTOCS case–control study was assayed using commercial p53 protein ELISA assay (Dianova GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) (Rohayem et al, 1999). In addition, all serial samples from women who had autoantibodies to p53 peptides in the microarray were tested.

Statistics

For each peptide, or p53 protein in the ELISA assay, sensitivity was determined at 95% specificity. Reactivity was defined as elevated if it was above the cutoff defined by the 95% percentile in the corresponding control samples. Sensitivity and AUC of the receiver operating characteristic curve were calculated. To investigate if combining the information of several key peptides (selected as those with sensitivity greater than 10% in the UKCTOCS samples when specificity was set at 95%) improves predictive performance, a multivariate classifier approach was evaluated. Four different discriminant analysis (DA) methods were assessed (linear, quadratic, logistic and kth nearest neighbour DA) using leave-one-out cross-validation, where the discriminant function was determined with each sample left out in turn, and then used to classify that sample.

Results

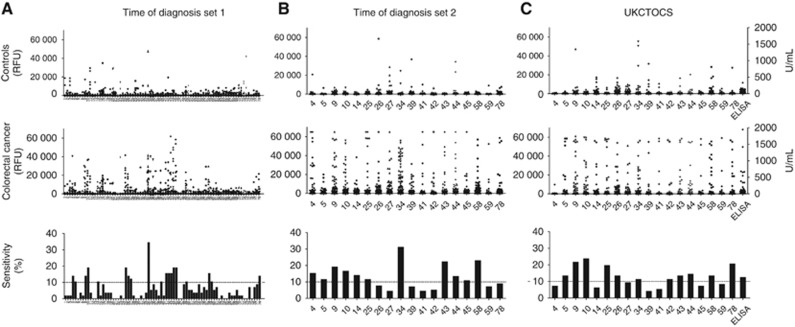

Sera obtained at the time of diagnosis were used for selecting relevant peptides (time of diagnosis sample set 1) and consisted of 58 colorectal cancer patients (male; n=33, female; n=25; mean age 60.3 years s.d. 7.5) and 53 controls (male; n=33, female; n=20; mean age 46.4 years s.d. 6.4). The patient sera were tested for autoantibodies to 15-mer p53 peptides covering the full sequence of the native p53. In all, 18 out of 78 p53 peptides (p53-4, -5, -9, -10, -14, -25, -27, -34, -39, -41, -45, -58, -59, -78) detected autoantibodies in 10% or more of the cancer patients with a specificity of 95% (Figure 1A). These peptides were selected and their biomarker value verified in a second set of serum samples (time of diagnosis sample set 2) to confirm the selected peptide targets. This set consisted of 157 (male=86, female=71) colorectal cancer patients whose mean age was 59.3 years s.d. 8.0. In all, 69 were stage I, 69 were stage II and 19 were stage III. The controls consisted of 40 subjects (male=20, female=20, mean age 38.7 years s.d. 7.7). Elevated levels of autoantibodies to 11 of the 18 p53 peptides (p53-4, -5, -9, -10, -14, -25, -34, -43, -44, -45, and -58) were found in over 10% of the cases (Figure 1B and Table 2). No obvious gender-related differences in p53 responses were found with the 18 selected peptides.

Figure 1.

Autoantibodies to p53 peptide (microarray) and p53 protein (ELISA) in time of diagnosis set I, time of diagnosis set II, and the UKCTOCS set. DOTPLOT of serum IgG autoantibodies binding to 15-mer scanning p53 peptides measured by peptide-array assay and expressed as relative fluorescence units (RFU) (y-axis). (A) Serum from healthy (n=53) and colorectal cancer individuals (n=58) (time of diagnosis #1). (B) Serum from healthy (n=40) and colorectal cancer individuals (n=157) in time of diagnosis set #2 (training set). (C) Serum from last sample before diagnosis in controls (n=94) and colorectal cancer (n=97) individuals from the UKCTOCS set. Bar graphs represent the sensitivity for each p53 peptide at 95% specificity.

Table 2. AUC and sensitivity for Asterand and UKCOTCS colorectal cancer patients.

|

AUC

|

Sensitivity (%)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | I–III | UKCTOCS | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | I–III | UKCTOCS |

| p53-4 | 0.5632 | 0.6196* | 0.5421 | 0.5848 | 0.5279 | 14.5 | 17.4 | 10.5 | 15.3 | 7.2 |

| p53-5 | 0.5319 | 0.5080 | 0.6039 | 0.5019 | 0.5627 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 13.4 |

| p53-9 | 0.6071 | 0.6061 | 0.5447 | 0.6018* | 0.6648*** | 17.4 | 21.7 | 15.8 | 19.1 | 21.6 |

| p53-10 | 0.6154* | 0.6382* | 0.6342 | 0.6275* | 0.6340** | 14.5 | 17.4 | 15.8 | 16.6 | 23.7 |

| p53-14 | 0.6562* | 0.6069 | 0.7382* | 0.6427** | 0.5651 | 10.1 | 11.6 | 21.1 | 14.0 | 6.2 |

| p53-25 | 0.5076 | 0.5493 | 0.5770 | 0.5275 | 0.5976* | 11.6 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 19.6 |

| p53-26 | 0.5255 | 0.5040 | 0.5763 | 0.5222 | 0.5472 | 4.3 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 13.4 |

| p53-27 | 0.5203 | 0.6054 | 0.5763 | 0.5644 | 0.5577 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 0 | 4.4 | 9.3 |

| p53-34 | 0.6306* | 0.7053* | 0.7895* | 0.6873*** | 0.5951* | 31.9 | 27.5 | 42.1 | 31.2 | 11.3 |

| p53-39 | 0.5355 | 0.5033 | 0.5434 | 0.5195 | 0.5103 | 7.2 | 2.9 | 21.1 | 7.0 | 4.1 |

| p53-41 | 0.5520 | 0.5366 | 0.5184 | 0.5374 | 0.5559 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 0 | 4.4 | 5.2 |

| p53-42 | 0.5350 | 0.5542 | 0.5092 | 0.5404 | 0.5032 | 4.3 | 7.2 | 0 | 5.1 | 11.3 |

| p53-43 | 0.6571** | 0.6808** | 0.5947 | 0.6589** | 0.5897* | 26.1 | 21.7 | 10.5 | 22.3 | 13.4 |

| p53-44 | 0.6348* | 0.5944 | 0.5434 | 0.6051* | 0.5810 | 15.9 | 8.7 | 10.5 | 13.4 | 14.4 |

| p53-45 | 0.6178* | 0.6121 | 0.6329 | 0.6172* | 0.5582 | 10.1 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 7.2 |

| p53-58 | 0.6504** | 0.6768** | 0.6493 | 0.6599** | 0.5664 | 20.3 | 27.5 | 15.8 | 22.9 | 13.4 |

| p53-59 | 0.5601 | 0.5534 | 0.5974 | 0.5419 | 0.5158 | 8.7 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 7.1 | 8.2 |

| p53-78 | 0.6304* | 0.5982 | 0.5303 | 0.6043* | 0.5454 | 11.6 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 8.9 | 20.6 |

Abbreviations: AUC=area under curve; UKCTOCS=United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening.

*P<0.05: **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Sensitivity at 95% specificity for time of diagnosis set II and UKCTOCS colorectal cancer cases.

In the UKCTOCS, 50 640 women were randomised to the multimodal group. Median follow-up was 6.78 (inter-quartile range 5.89–8.43) years. Colorectal cancer notification was received for 101 women who had donated more than one sample before diagnosis. A total of 97 (297 serial samples) women with colorectal cancer of the 101 who had given consent for secondary studies and 97 age-matched controls (296 serial samples) were initially included in the study. Three controls were subsequently excluded from the analysis because of notification of cancer diagnosis at final follow-up. The majority of the cases were diagnosed before the roll out of the bowel cancer screening programme in the United Kingdom. Of the 97 women, there were 2 (2%) women diagnosed in 2003, 9 (9%) in 2004, 22 (23%) in 2005, 29 (30%) in 2006, 31 (32%) in 2007, and 4 (4%) in 2008. Up-to-date cancer registration data for this study was obtained in December 2009 and the small number of women with colorectal cancer diagnosed in 2008 reflects the delay in central registration of cancer (Fourkala et al, 2012).

The mean age at randomisation was 65.1 (s.d. 5.8) for cases and 64.6 (s.d. 5.9) for controls. There were no difference in baseline characteristics between cases and controls except for possible higher use of hormone replacement therapy at recruitment in those who developed colorectal cancer (P=0.028). There was no difference in p53 peptide response in controls when we compared HRT users with non-HRT users, where Mann–Whitney tests showed a non-significant result for all 18 peptides (P-values ranged between 0.067 and 0.916).

In samples from the UKCTOCS set taken nearest to diagnosis, autoantibodies to 11 of the 18 p53 peptides were elevated in over 10% of cases (p53-5, -9, -10, -25, -26, -34, -42, -43, -44, -58, -78), of which 8 peptides were identical to the peptides identified in the time of diagnosis sample set 2. The two best performing peptides, p53-9 and p53-10, each detected 21.6% and 23.7% of the colorectal cancer patients, respectively, whereas the peptides p53-5, -25, -34, -43, -44 and -58 each detected between 10% and 20% of the patients with a 95% specificity, which is similar to the results obtained with time of diagnosis sample set 2 (Figure 1C and Table 2). Three additional peptides had sensitivities over 10% only in the UKCTOCS set, p53-26, p53-42 and p53-78 detecting 13.4%, 11.3%, and 20.6%, respectively, of patients with 95% specificity. In contrast, p53-4 and p53-34 failed to demonstrate the same sensitivity in UKCTOCS as seen in the time of diagnosis set. No evidence was found of any association between the age of the patients and the presence of autoantibodies, excluding differences in age between the different sample sets as a possible explanation of the small differences in recognised p53 epitopes.

The four best performing peptides in the UKCTOCS cases (p53-9, p53-10, p53-25, p53-78), were selected to form part of a DA aiming to correctly classify each sample in turn using a discriminant function based on the remaining samples (‘leave-one-out’ cross-validation) (Supplementary data 2). Quadratic DA demonstrated a sensitivity of 25.8% at 95% specificity. Using the ‘leave-one-out’-predicted probabilities to create a receiver operating characteristic curve, the AUC was calculated as 0.608 (95% CI: 0.527–0.688). Kth nearest neighbour DA achieved an AUC of 0.674 (95% CI: 0.597, 0.750) but only had a sensitivity of 16.5% at 95% specificity.

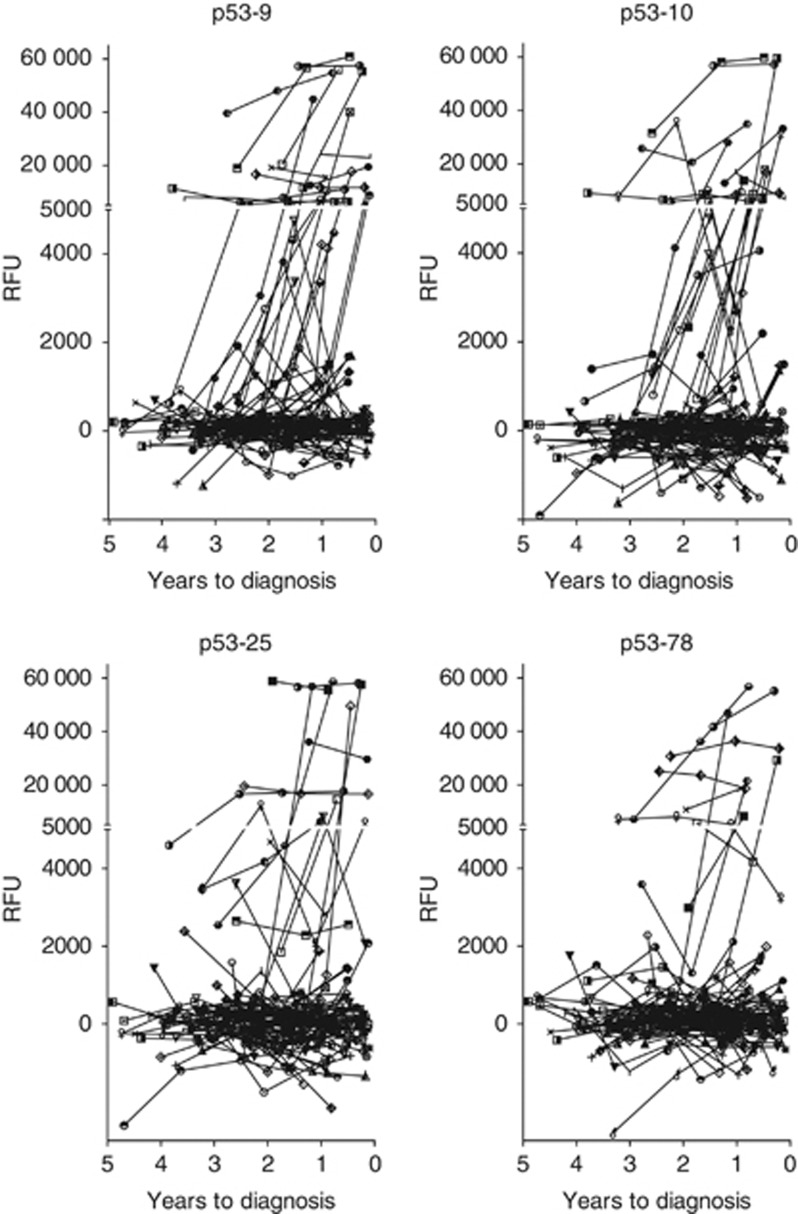

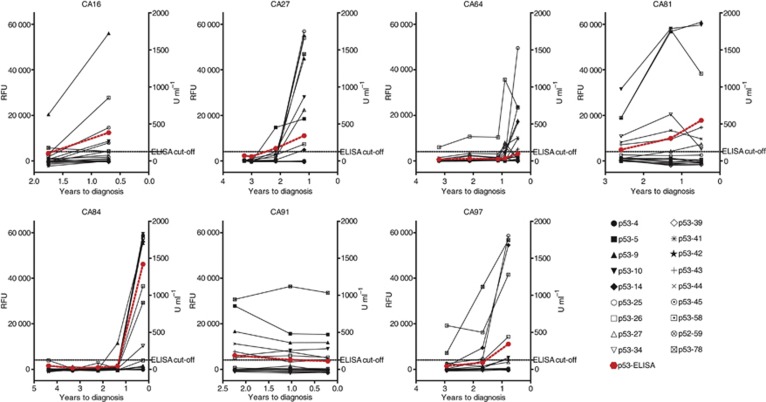

Analysis of serial samples taken before diagnosis in individual cancer cases demonstrated early development of autoantibodies to the top four (p53-9, -10, -25, -78) of the 11 immunogenic p53 epitopes (Figure 2; remaining peptides in Supplementary data 3). Autoantibodies to p53-10 were detected in 23 colorectal cancer cases and were already detectable in 10 of the patients at the time the first serum sample was collected, a median of 2.1 years (range 1.0–3.8) before diagnosis. In the remaining 13 patients, p53-10 autoantibodies developed at a median of 0.8 (range 0.1–2.6) years before diagnosis. Overall, the four most informative peptides collectively identified colorectal cancer patients at a median lead time of 1.4 (range 0.1–3.8) years before clinical diagnosis. Specificity was 95%. As time progressed additional peptides were recognised, demonstrating epitope spread most likely consequent on increasing accumulation of mutated p53 (Figure 3, Supplementary data 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Autoantibodies in pre-diagnostic serial samples from colorectal cancer patients (n=97) to selected p53 peptides. Each graph represents the autoantibody reactivity to peptide p53-9, p53-10, p53-25, p53-78. Each symbol represents a single cancer patient. Number of years before diagnosis is indicated on the x-axis. y-axis represents relative fluorescence units (RFU).

Figure 3.

Pre-diagnostic serial samples from selected colorectal cancer patients to p53 peptides. Each graph represents a single colorectal cancer patient and autoantibodies to all the 18 p53 peptides investigated in the validation set. x-axis represents number of years before diagnosis. Graphs for p53 protein ELISA are marked with red colour. Left y-axis represents relative fluorescence units (RFU). Right y-axis represents U ml−1 for ELISA results.

Using a p53 protein ELISA test, 11 cases tested positive compared with the 25 cases that tested positive with the peptide array (Figure 1C, Supplementary data 5). When serial samples were analysed, we detected 11 cases 1.2 years before time of diagnosis with the ELISA assay compared, whereas this was extended to 1.4 years before diagnosis using the most informative p53 peptides on the microarray (Figure 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study in the general population exploring the development of p53 autoantibodies using serial samples taken from women before clinical diagnosis of cancer. p53 autoantibodies were found in 26% of colorectal patients with a median lead time of 1.4 (range 0.12–3.8) years and a specificity of 95%. Early development of autoantibodies to certain immunogenic p53 epitopes was followed by autoantibodies to additional peptides as time progressed towards diagnosis.

The strengths of our study included use of (1) a prospective-specimen collection, retrospective-blinded-evaluation study design (Pepe et al, 2008), (2) a cohort where the screening intervention had minimal impact on the incidence of the cancer of interest – colorectal in our study, (3) detailed follow-up using the national cancer registry, (4) inclusion of samples from 96% of women with serial samples who were identified to have developed colorectal cancer after randomisation, (5) no significant difference in baseline characteristics of cases and controls, (6) blinded assay to avoid handling bias, and (7) simultaneous and sensitive detection of autoantibodies to multiple target epitopes. The main limitation is that data were not available with regard to mode of diagnosis or stage of the cancers, as this was not provided by the cancer registry. As most of the cancers were diagnosed before implementation of the UK colorectal screening programme (National Health Service UK; http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/bowel), it is likely that they were diagnosed following symptomatic presentation. In addition, although the cohort was recruited through random invitation from population registers, it has lower mortality rates compared with the general population due to a healthy volunteer effect (Burnell et al, 2011). However, it is likely that a similar healthy volunteer effect exists in individuals enrolled in screening programmes for colorectal cancer.

Hormone replacement therapy use at recruitment was higher in those who developed colorectal cancer (P<0.05). This is in keeping with recent data from prospective cohort studies, where a positive association between serum oestrogen and colorectal cancer risk has been noted (Zervoudakis et al, 2011). Although hormone replacement therapy has been reported to have confounding effects in protein biomarker studies (Pitteri and Hanash, 2011), we found no difference in p53 peptide response in the controls when we compared HRT users in the controls with non-users. This suggests that it is unlikely that the observed differences in p53 autoantibodies between cancer patients and controls were related to HRT use.

We detected autoantibodies in pre-diagnostic samples of 25.8% of colorectal cancer patients with a specificity of 95%. This is in keeping with clinical studies, which have found autoantibodies to p53 at diagnosis in 5–24% of colorectal cancer patients (Houbiers et al, 1995; Sthoeger et al, 1997; Hallak et al, 1998; Kressner et al, 1998; Tang et al, 2001; Lechpammer et al, 2004; Saleh et al, 2004; Suppiah et al, 2008; Liu et al, 2009). Several peptide sequences from the p53 protein were identified as potential targets for autoantibody reactivity in the colorectal cancer patients. These were primarily located in the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions, outside the mutation hotspots of the protein (Lubin et al, 1993; Schlichtholz et al, 1994). It has been suggested that cancer-selective immuno-dominant p53 epitopes may help decrease false-positives and increase specificity assays (Schlichtholz et al, 1994; Vennegoor et al, 1997). Our findings suggest that a selected p53-peptide biomarker assay has higher sensitivity and specificity compared with an ELISA assay using full-length denatured p53 protein (Figures 1 and 3, Supplementary data 5).

The present study shows that p53 antibodies can be detected before diagnosis in a cohort of randomly selected normal-risk individuals. p53 autoantibodies had already developed in 10 of the 97 women at the time the first serum sample was collected 1.0–3.8 years before clinical diagnosis, whereas 13 women seroconverted during the course of the study 0.1–2.6 years before diagnosis. The lead time associated with p53 autoantibodies varied between the cancer patients from 3.8 years to less than 1 year before diagnosis. These findings are in keeping with a recent study on the presence of autoantibodies to HER2 and p53 in serum from breast cancer patients collected on average 153 days before time of diagnosis (Lu et al, 2012). Similarly, autoantibodies to p53 have been reported before diagnosis of lung cancer in small cohorts of high-risk patients with COPD (Lubin et al, 1995; Trivers et al, 1996) or asbestosis, with an average lead time of 3.5 years (range: 1–12 years) (Li et al, 2005). In addition, p53 autoantibodies have also been described before diagnosis of a variety of malignancies (Trivers et al, 1995), but these earlier studies all have been limited to analysis of small number of patients in high-risk cohorts or at a single time point before diagnosis (Lubin et al, 1995; Trivers et al, 1995, 1996; Soussi, 2000; Li et al, 2005; Zhong et al, 2006; Qiu et al, 2008). In our study, autoantibodies to p53 peptides increased as time progressed towards diagnosis, which is consistent with studies demonstrating an association between p53 autoantibodies and stage at diagnosis; in a study of 998 colorectal cancer patients, p53 autoantibodies were detectable in 29% with over 10 positive nodes, 12% with negative nodes, and 6% with carcinoma in situ (Tang et al, 2001).

Although p53 autoantibodies do not possess sufficient diagnostic sensitivity to be used as the sole screening test, they could be combined with demographic and clinical parameters to build risk stratification scores needed in current colorectal screening programs. There are a plethora of validated screening tests with high specificities and reasonable sensitivities (colono/sigmoidoscopy, CT/MR colonography, capsule endoscopy, faecal DNA, and occult blood) but a major issue with these procedures is limited compliance. The hope is that a ‘risk assessment evaluation’ test may lead to higher acceptance of these procedures and improve compliance among the screening populations (Nielsen et al, 2011). At present, a large Danish study of over 5000 individuals is underway to validate a risk assessment evaluation for colorectal cancer that combines demographic and clinical data with the biomarkers, carcino-embryonic antigen and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (Nielsen et al, 2011). There is also the possibility of using methylation markers as part of such a risk assessment strategy in the future (Li et al, 2009; Tanzer et al, 2010).

Many studies have combined markers to increase sensitivity of diagnostic autoantibody tests (Wang et al, 2005; Chatterjee et al, 2006), and an autoantibody test consisting of a combination of six antigens, including p53 (p53, NY-ESO-1, CAGE, GBU4-5, Annexin 1, and SOX2) has been validated in a large screening study of high-risk individuals for lung cancer (Boyle et al, 2011). In addition, it was recently shown that a combination of p53 autoantibodies and CA125 levels increased sensitivity for ovarian cancer from 73.8% (CA125) to 85.7% (CA 125+p53 autoantibodies) (Lu et al, 2011), illustrating the potential in combining well-known biomarkers with autoantibodies to p53.

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale general population study exploring lead time of p53 autoantibodies in individuals before clinical diagnosis of cancer. The finding that p53 autoantibodies were elevated in one in four colorectal cancer patients up to 3.8 years before clinical diagnosis suggests that autoantibody signatures may be of value in risk stratification and cancer screening particularly in colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Karin Uch Hansen and Susanne Johannesen for excellent technical assistance. We are particularly grateful to the women throughout the United Kingdom who are participating in the UKCTOCS trial, to the entire medical, nursing, and administrative staff who work on the UKCTOCS and to the independent members of the oversight committees. This work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, Danish Medical Research Council, The Danish Cancer Research Foundation, Agnes and Poul Friis Foundation, a programme of excellence from the University of Copenhagen. The trial was core funded by the Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK, and the Department of Health, with additional support from the Eve Appeal, Special Trustees of Bart’s and the London, and Special Trustees of University College London Hospital (UCLH). A large portion of this work was done at UCLH/UCL within the ‘women’s health theme’ of the National Institute for Health Research UCLH/UCL Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre supported by the Department of Health. The researchers are independent from the funders.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

UM and IJ have a financial interest through UCL Business and Abcodia Ltd in the third-party exploitation of clinical trials biobanks, which have been developed through the research at UCL. IJ has consultancy arrangements with Becton Dickinson, who have provided consulting fees, funds for research, and staff but not directly related to this study. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Boyle P, Chapman CJ, Holdenrieder S, Murray A, Robertson C, Wood WC, Maddison P, Healey G, Fairley GH, Barnes AC, Robertson JF (2011) Clinical validation of an autoantibody test for lung cancer. Ann Oncol 22: 383–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell M, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, Apostolidou S, Habib M, Kalsi J, Skates S, Parmar M, Seif MW, Amso NN, Godfrey K, Oram D, Herod J, Williamson K, Jenkins H, Mould T, Woolas R, Murdoch J, Dobbs S, Leeson S, Cruickshank D, Campbell S, Fallowfield L, Jacobs I, Menon U (2011) Impact on mortality and cancer incidence rates of using random invitation from population registers for recruitment to trials. Trials 12: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey G, Lopez ME, Ramos JC, Plummer SJ, Arboleda MJ, Shaughnessy M, Karlan B, Slamon DJ (1996) DNA sequence analysis of exons 2 through 11 and immunohistochemical staining are required to detect all known p53 alterations in human malignancies. Oncogene 13: 1971–1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Mohapatra S, Ionan A, Bawa G, Ali-Fehmi R, Wang X, Nowak J, Ye B, Nahhas FA, Lu K, Witkin SS, Fishman D, Munkarah A, Morris R, Levin NK, Shirley NN, Tromp G, Abrams J, Draghici S, Tainsky MA (2006) Diagnostic markers of ovarian cancer by high-throughput antigen cloning and detection on arrays. Cancer Res 66: 1181–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourkala EO, Gentry-Maharaj A, Burnell M, Ryan A, Manchanda R, Dawnay A, Jacobs I, Widschwendter M, Menon U (2012) Histological confirmation of breast cancer registration and self-reporting in England and Wales: a cohort study within the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening. Br J Cancer 106: 1910–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallak R, Mueller J, Lotter O, Gansauge S, Gansauge F, el-Deen Jumma M, Montenarh M, Safi F, Beger H (1998) p53 genetic alterations, protein expression and autoantibodies in human colorectal carcinoma: a comparative study. Int J Oncol 12: 785–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houbiers JG, van der Burg SH, van de Watering LM, Tollenaar RA, Brand A, van de Velde CJ, Melief CJ (1995) Antibodies against p53 are associated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 72: 637–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs I, Menon U (2011) The sine qua non of discovering novel biomarkers for early detection of ovarian cancer: carefully selected preclinical samples. Cancer Prev Res 4: 299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressner U, Glimelius B, Bergstrom R, Pahlman L, Larsson A, Lindmark G (1998) Increased serum p53 antibody levels indicate poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 77: 1848–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque S, Naor N, Thomson D, Matlashewski G (1993) Analysis of the anti-p53 antibody response in cancer patients. Cancer Res 53: 3468–3471 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechpammer M, Lukac J, Lechpammer S, Kovacevic D, Loda M, Kusic Z (2004) Humoral immune response to p53 correlates with clinical course in colorectal cancer patients during adjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis 19: 114–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Chen WD, Papadopoulos N, Goodman SN, Bjerregaard NC, Laurberg S, Levin B, Juhl H, Arber N, Moinova H, Durkee K, Schmidt K, He Y, Diehl F, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Kinzler KW, Markowitz SD, Vogelstein B (2009) Sensitive digital quantification of DNA methylation in clinical samples. Nat Biotechnol 27: 858–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Karjalainen A, Koskinen H, Hemminki K, Vainio H, Shnaidman M, Ying Z, Pukkala E, Brandt-Rauf PW (2005) p53 autoantibodies predict subsequent development of cancer. Int J Cancer 114: 157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Wang P, Li Z, Xu W, Dai L, Wang K, Zhang J (2009) Evaluation of tumour-associated antigen (TAA) miniarray in immunodiagnosis of colon cancer. Scand J Immunol 69: 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Kuhn E, Bristow RE, Giuntoli RL, Kjaer SK, Shih IM, Roden RB (2011) Comparison of candidate serologic markers for type I and type II ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 122: 560–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Ladd J, Feng Z, Wu M, Goodell V, Pitteri SJ, Li CI, Prentice RL, Hanash SM, Disis ML (2012) Evaluation of known oncoantibodies, HER2, p53, and cyclin B1, in pre-diagnostic breast cancer sera. Cancer Prev Res 5: 1036–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin R, Schlichtholz B, Bengoufa D, Zalcman G, Tredaniel J, Hirsch A, de Fromentel CC, Preudhomme C, Fenaux P, Fournier G, Mangin P, Laurent-Puig P, Pelletier G, Schlumberger M, Desgrandchamps F, Le Duc A, Peyrat JP, Janin N, Bressac B, Soussi T (1993) Analysis of p53 antibodies in patients with various cancers define B-cell epitopes of human p53: distribution on primary structure and exposure on protein surface. Cancer Res 53: 5872–5876 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin R, Zalcman G, Bouchet L, Tredanel J, Legros Y, Cazals D, Hirsch A, Soussi T (1995) Serum p53 antibodies as early markers of lung cancer. Nat Med 1: 701–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Hallett R, Ryan A, Burnell M, Sharma A, Lewis S, Davies S, Philpott S, Lopes A, Godfrey K, Oram D, Herod J, Williamson K, Seif MW, Scott I, Mould T, Woolas R, Murdoch J, Dobbs S, Amso NN, Leeson S, Cruickshank D, McGuire A, Campbell S, Fallowfield L, Singh N, Dawnay A, Skates SJ, Parmar M, Jacobs I (2009) Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol 10: 327–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, Sharma A, Burnell M, Hallett R, Lewis S, Lopez A, Godfrey K, Oram D, Herod J, Williamson K, Seif M, Scott I, Mould T, Woolas R, Murdoch J, Dobbs S, Amso N, Leeson S, Cruickshank D, McGuire A, Campbell S, Fallowfield L, Skates S, Parmar M, Jacobs I (2008) Recruitment to multicentre trials – lessons from UKCTOCS: descriptive study. BMJ 337: a2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen HJ, Jakobsen KV, Christensen IJ, Brunner N (2011) Screening for colorectal cancer: possible improvements by risk assessment evaluation? Scand J Gastroenterol 46: 1283–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen JW, Blixt O, Bennett EP, Tarp MA, Dar I, Mandel U, Poulsen SS, Pedersen AE, Rasmussen S, Jess P, Clausen H, Wandall HH (2011) Seromic profiling of colorectal cancer patients with novel glycopeptide microarray. Int J Cancer 128: 1860–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt PM, Potter JD (2008) Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 1432–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitteri SJ, Hanash SM (2011) Confounding effects of hormone replacement therapy in protein biomarker studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 134–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Choi G, Li L, Wang H, Pitteri SJ, Pereira-Faca SR, Krasnoselsky AL, Randolph TW, Omenn GS, Edelstein C, Barnett MJ, Thornquist MD, Goodman GE, Brenner DE, Feng Z, Hanash SM (2008) Occurrence of autoantibodies to annexin I, 14-3-3 theta and LAMR1 in prediagnostic lung cancer sera. J Clin Oncol 26: 5060–5066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohayem J, Conrad K, Zimmermann T, Frank KH (1999) Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of three commercially available enzyme immunoassays for anti-p53 antibodies. Clin Chem 45: 2014–2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh J, Kreissler-Haag D, Montenarh M (2004) p53 autoantibodies from patients with colorectal cancer recognize common epitopes in the N- or C-terminus of p53. Int J Oncol 25: 1149–1155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichtholz B, Legros Y, Gillet D, Gaillard C, Marty M, Lane D, Calvo F, Soussi T (1992) The immune response to p53 in breast cancer patients is directed against immunodominant epitopes unrelated to the mutational hot spot. Cancer Res 52: 6380–6384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichtholz B, Tredaniel J, Lubin R, Zalcman G, Hirsch A, Soussi T (1994) Analyses of p53 antibodies in sera of patients with lung carcinoma define immunodominant regions in the p53 protein. Br J Cancer 69: 809–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussi T (2000) p53 antibodies in the sera of patients with various types of cancer: a review. Cancer Res 60: 1777–1788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sthoeger Z, Evron E, Goland S, Shani A, Wolkowicz R, Goldfinger N, Rotter V, Fogel M (1997) Anti-p53 autoantibodies in colon cancer patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 815: 496–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppiah A, Alabi A, Madden L, Hartley JE, Monson JR, Greenman J (2008) Anti-p53 autoantibody in colorectal cancer: prognostic significance in long-term follow-up. Int J Colorectal Dis 23: 595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang R, Ko MC, Wang JY, Changchien CR, Chen HH, Chen JS, Hsu KC, Chiang JM, Hsieh LL (2001) Humoral response to p53 in human colorectal tumors: a prospective study of 1,209 patients. Int J Cancer 94: 859–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzer M, Balluff B, Distler J, Hale K, Leodolter A, Rocken C, Molnar B, Schmid R, Lofton-Day C, Schuster T, Ebert MP (2010) Performance of epigenetic markers SEPT9 and ALX4 in plasma for detection of colorectal precancerous lesions. PLoS One 5: e9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers GE, Cawley HL, DeBenedetti VM, Hollstein M, Marion MJ, Bennett WP, Hoover ML, Prives CC, Tamburro CC, Harris CC (1995) Anti-p53 antibodies in sera of workers occupationally exposed to vinyl chloride. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 1400–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers GE, De Benedetti VM, Cawley HL, Caron G, Harrington AM, Bennett WP, Jett JR, Colby TV, Tazelaar H, Pairolero P, Miller RD, Harris CC (1996) Anti-p53 antibodies in sera from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can predate a diagnosis of cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2: 1767–1775 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennegoor CJ, Nijman HW, Drijfhout JW, Vernie L, Verstraeten RA, von Mensdorff-Pouilly S, Hilgers J, Verheijen RH, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Kenemans P (1997) Autoantibodies to p53 in ovarian cancer patients and healthy women: a comparison between whole p53 protein and 18-mer peptides for screening purposes. Cancer Lett 116: 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yu J, Sreekumar A, Varambally S, Shen R, Giacherio D, Mehra R, Montie JE, Pienta KJ, Sanda MG, Kantoff PW, Rubin MA, Wei JT, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM (2005) Autoantibody signatures in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 353: 1224–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter SF, Minna JD, Johnson BE, Takahashi T, Gazdar AF, Carbone DP (1992) Development of antibodies against p53 in lung cancer patients appears to be dependent on the type of p53 mutation. Cancer Res 52: 4168–4174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervoudakis A, Strickler HD, Park Y, Xue X, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A, Gunter MJ (2011) Reproductive history and risk of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 826–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Coe SP, Stromberg AJ, Khattar NH, Jett JR, Hirschowitz EA (2006) Profiling tumor-associated antibodies for early detection of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 1: 513–519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.