Abstract

Background:

Endo180 (CD280; MRC2; uPARAP)-dependent collagen remodelling is dysregulated in primary tumours and bone metastasis. Here, we confirm the release and diagnostic accuracy of soluble Endo180 for diagnosing metastasis in breast cancer (BCa).

Methods:

Endo180 was quantified in BCa cell conditioned medium and plasma from BCa patients stratified according to disease status and bisphosphonate treatment (n=88). All P-values are from two-sided tests.

Results:

Endo180 is released by ectodomain shedding from the surface of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 BCa cell lines. Plasma Endo180 was significantly higher in recurrent/metastatic (1.71±0.87; n=59) vs early/localised (0.92±0.37; n=29) BCa (P<0.0001). True/false-positive rates for metastasis classification were: 85%/50% for the reference standard, CA 15-3 antigen (28 U ml−1); ⩽97%/⩾36% for Endo180; and ⩽97%/⩾32% for CA 15-3 antigen+Endo180. Bisphosphonate treatment was associated with reduced Endo180 levels in BCa patients with bone metastasis (P=0.011; n=42). True/false-positive rates in bisphosphonate-naive patients (n=57) were: 68%/45% for CA 15-3 antigen; ⩽95%/⩾20% for Endo180; and ⩽92%/⩾21% for CA 15-3 antigen+Endo180.

Conclusion:

Endo180 is a potential marker modulated by bisphosphonates in metastatic BCa.

Keywords: bisphosphonates, bone metastasis, breast cancer, collagen receptor, diagnostic marker, plasma marker

Breast cancer (BCa) is the most frequent malignancy in women in the economically developed world (Ferlay et al, 2010). Despite introduction of screening and advances in adjuvant therapy, approximately one-third of early BCa patients will go on to develop metastatic disease involving visceral organs and/or bone (Peto et al, 2012). In the majority of European centres, metastatic BCa is monitored using the serum marker CA 15-3 antigen (Duffy et al, 2010), an epitope in the highly glycosylated transmembrane protein mucin-1 (MUC-1) that is shed from the tumour cell surface (Thathiah et al, 2003; Thathiah and Carson, 2004). Latest recommendations for tumour markers in locally recurrent or metastatic BCa published by the American Association of Clinical Oncology in November 2007 (Harris et al, 2007) and the European Society for Medical Oncology in June 2011 (Cardoso et al, 2011) conclude that CA 15-3 antigen is useful as a marker together with, but not as a replacement for, diagnostic imaging and routine clinical assessment. Identification of markers that are more sensitive, either alone or in combination with CA 15-3 antigen, may help to improve this current diagnostic limitation for metastatic BCa.

Endo180 (CD280; MRC2; urokinase plasminogen activator-associated protein; uPARAP) is a 180-kDa type 1 transmembrane receptor that interacts with extracellular and intracellular collagens (Wienke et al, 2003). Endo180 expression is correlated with tumour grade, disease progression and poor prognosis in BCa (Wienke et al, 2007), head and neck cancer (Sulek et al, 2007), prostate cancer (Kogianni et al, 2009) and glioblastoma multiforme (Huijbers et al, 2010). Endo180-dependent collagen remodelling has mechanistic roles in the promotion of BCa progression (Curino et al, 2005; Wienke et al, 2007) and metastatic bone lesion pathology (Caley et al, 2011). In this study, we report that Endo180 ectodomain is released from BCa cells and measurement of soluble Endo180 in plasma, alone or in combination with CA 15-3 antigen, provides an accurate method for the classification of metastatic disease. The results also indicate that Endo180 levels are modulated following treatment with bisphosphonates.

Patients and methods

Preparation of conditioned medium and cell lysates

MCF-7-Endo180 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured as previously described (Sturge et al, 2003, 2006; Wienke et al, 2007). Protein was precipitated from conditioned medium and cell lysates prepared as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Immunoblot analysis

Conditioned medium pellets and corresponding cell lysates were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). Immunoblot analysis was carried out using A5/158 or 39.10 mouse anti-human Endo180 monoclonal antibodies (1 μg ml−1) or CAT-2 rabbit anti-mouse Endo180 polyclonal antibody (1.5 μg ml−1) (Sturge et al, 2003, 2006, 2007; Wienke et al, 2007; Kogianni et al, 2009; Huijbers et al, 2010; Caley et al, 2011) as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Patients

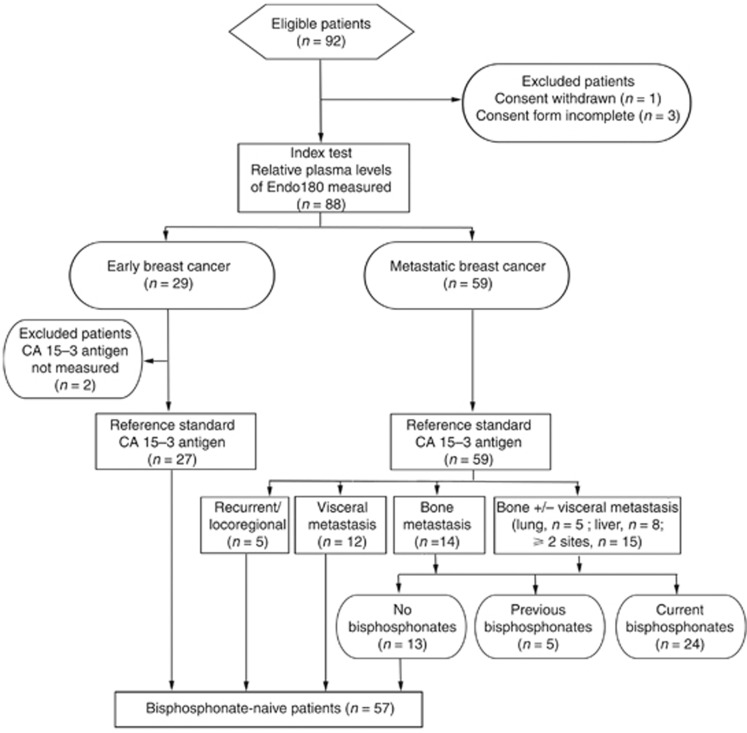

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Tissue Bank Committee (REC reference 07/MRE09/54). The study population was restricted to a consecutive series of 92 patients with histologically confirmed BCa who attended breast oncology clinics at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust between 4 March 2011 and 29 August 2011 and was designed following the guidelines of Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy studies (STARD) (Bossuyt et al, 2003). Three patients were excluded from the study due to incorrect completion of consent forms and one patient who originally agreed to enter the study withdrew consent (Figure 1). Treatment followed the standard of care that patients normally receive at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. Early BCa was defined as a localised tumour previously treated with definitive surgery, systemic therapy and adjuvant radiotherapy (as clinically indicated) or receiving on-going (neo)-adjuvant systemic therapy. All early BCa patients had a staging investigation that was negative with no evidence of recurrent disease at outpatient review when blood samples were collected. Metastatic disease sites were determined from the most recent radiological evaluation. The definition of visceral metastasis was radiological evidence of recurrent disease involving the pleura, peritoneum or lymph nodes (paratracheal, axillary, mediastinal, supraclavicular, infraclavicular) or lesions in visceral organs (liver, lung, spleen). The definition of bone metastasis was the detection of osseous lesions by bone scintigraphy, computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging. Exclusion criteria were inadequate haematological and/or biochemical parameters.

Figure 1.

Details of patients included in the study. Number of patients recruited and excluded is shown together with those for whom index and reference standard tests were performed. Numbers of patients with recurrent/locoregional disease, visceral metastasis, bone metastasis alone or bone metastasis with visceral metastasis in lung, liver or more than one visceral site are indicated. Numbers of patients who were bisphosphonate naive, had previously received, or were currently receiving, bisphosphonates are shown.

Plasma preparation and analysis

Plasma samples were collected and Endo180 and CA 15-3 antigen levels were analysed as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Advisory Service (Imperial College London) used SPSS software to predict that 17 patients would be necessary for each patient group to detect low-to-moderate correlation between variables (α=5% probability, type 1 error significance level; 95% power; 50% confidence interval (CI); 40% standard deviation). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to determine assumed linearity. Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness of fit was used to test likelihood of a normal distribution at 95% confidence. John Tukey criteria defined outliers as values that were 1.5 times above the third quartile (Q3) or below the first quartile (Q1). Non-parametric tests were used to calculate the probability (P) of a significant difference (95% CI). Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparison between two groups. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance was used for comparison between more than two groups. Where statistical differences were found, Bonferonni multiple comparisons adjustment was applied to confirm pairwise differences. For Bonferonni correction, the overall type I error constraint was set to 0.05 and the level of statistical significance was set to 0.05/n, where n is the number of tests. P-values<0.05/n were considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided. The test used for each analysis is cited in the text and figure legends.

Results

Release of soluble Endo180

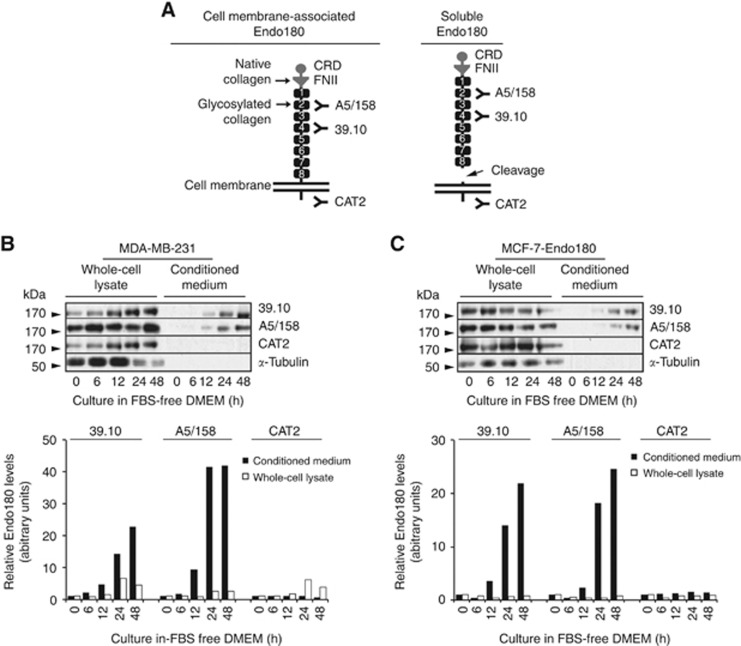

Viable disease markers are released into the circulation in appreciable and easily detectable amounts (Diamandis, 2010). Antibodies that bind epitopes in the ectodomain (A5/158 and 39.10) (Sturge et al, 2003) or intracellular domain (CAT-2) (Sturge et al, 2007) of Endo180 (Figure 2A) were used to immunoblot whole-cell lysates and corresponding conditioned media from MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7-Endo180 cells, in which the receptor enhances their pro-tumorigenic and metastatic behaviour (Sturge et al, 2003, 2006; Wienke et al, 2003, 2007). Endo180 detection by all three antibodies in MDA-MB-231 (Figure 2B) and MCF-7-Endo180 (Figure 2C) whole-cell lysates; and by A5/158 and 39.10, but not CAT-2, in corresponding conditioned media confirmed that Endo180 ectodomain is released in a soluble form from BCa cells. Soluble Endo180 levels were increased in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7-Endo180 cell conditioned media by 9.5-fold (after 12 h) and 42-fold (after 24 and 48 h) culture in serum-free medium (Figure 2B and C).

Figure 2.

Endo180 is cell membrane-associated or released in soluble form in monolayers of human BCa cell lines cultured under serum-free conditions. (A) The domain structure of cell membrane-associated Endo180. The cysteine-rich domain (CRD), fibronectin type II domain (FNII) and C-type lectin-like domains (CTLDs), of which there are eight (1–8); and binding sites of the known ligands for FNII (native collagen) and CTLD-2 (glycosylated collagen and sugar moieties); are shown. Three anti-Endo180 antibodies and their respective epitopes are depicted: mouse anti-human Endo180 monoclonal antibody 39.10 is mapped to bind CTLD-4 (unpublished); mouse anti-human Endo180 monoclonal antibody A5/158 is mapped to bind CTLD-2 (Sturge et al, 2003); and rabbit anti-mouse CAT-2 monoclonal antibody was raised against the conserved 42 amino-acid intracellular domain of mouse Endo180 and has equal affinity for the detection of the receptor in human cell lysates (Sturge et al, 2007; Caley et al, 2011). The domain structure of soluble Endo180 ectodomain following its juxtamembrane cleavage and predicted detection by 39.10 and A5/158 antibodies, but not CAT-2 antibody, is also shown. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells and (C) MCF-7 cells that overexpress Endo180 (MCF-7-Endo180) were cultured in DMEM without fetal bovine serum for 0 (time zero), 6, 12, 24 and 48 h at which time whole-cell lysates and corresponding conditioned medium were collected. Samples were resolved on 8% w/v SDS polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and immunoblot analysis was performed using the three anti-Endo180 monoclonal antibodies: 39.10 (1 mg ml−1), A5/158 (1 mg ml−1) and CAT-2 (1.5 mg ml−1); and α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1/1000 dilution) and horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1/4000 dilution). Representative immunoblots from 10 experimental repeats are presented with corresponding graphs showing relative Endo180 levels calculated by the densitometric analysis of 39.10, A5/158 and CAT-2 immunoreactive bands. Relative Endo180 levels in conditioned media (black bars) were calculated by normalisation against relative Endo180 levels at time zero (relative Endo180 level=1.0) for all subsequent time points (6, 12, 18 and 24 h). Relative Endo180 levels in cell lysates (white bars) were adjusted against the level of α-tubulin and normalised against the relative Endo180 levels at time zero (relative Endo180 level=1.0) for all subsequent time points (6, 12, 18 and 24 h). The markers of molecular weight in kilodaltons (kDa) are indicated using black arrowheads for each immunoblot.

Detection of soluble Endo180 in plasma

Immunodetection of Endo180 by 39.10 antibody in human tissue and cell lysates has been well characterised (Wienke et al, 2007; Kogianni et al, 2009; Huijbers et al, 2010; Caley et al, 2011) and was adapted here as a research assay in accordance with recommendations for initial biomarker discovery where no commercial test exists (Pepe et al, 2008). A single and easily quantifiable 180 kDa immunoreactive band could be detected by 39.10 antibody in plasma resolved using SDS–PAGE (Supplementary Figure 1).

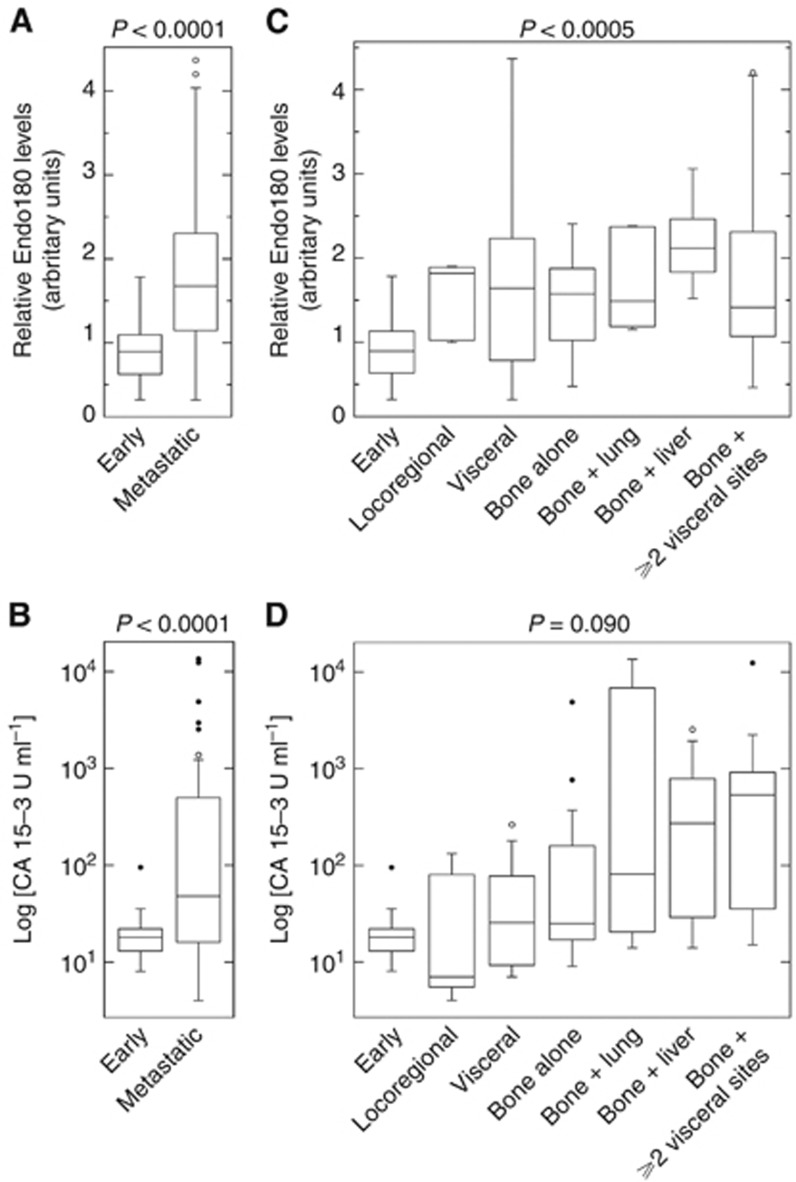

Elevated Endo180 in metastatic BCa

Endo180 levels in plasma collected from 88 BCa patients (Figure 1) did not correlate with their clincopathological characteristics or current treatment (Supplementary Data; Supplementary Tables 1–3). The median time from diagnosis of patients with early BCa (n=29) was 5 months (range=0–180 months; Q1: 3 months; Q3: 25 months) and with metastatic BCa (n=59) was 60 months (range=0–300 months; Q1: 17 months; Q3: 156 months). The range of relative Endo180 plasma levels in early BCa cases (n=29) was consistent with a normal distribution (P=0.69; mean±s.d.=0.92±0.37; range=0.32–1.78; Q1: 0.63; Q3: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.78–1.06, Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness of fit), indicating that Endo180 release into plasma during early BCa is a tightly regulated event. Relative Endo180 levels in recurrent/metastatic BCa (n=59) were significantly elevated compared with early BCa (P<0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-test) and inconsistent with a normal distribution (P=0.01; mean±s.d.=1.71±0.87; range=0.32–4.37; Q1: 1.13; Q3: 2.30; 95% CI: 1.49–1.94, Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness of fit) (Figure 3A), indicating that dysregulated Endo180 release occurs at this advanced disease stage. As expected, CA 15-3 antigen levels were significantly higher (P<0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-test) in recurrent/metastatic (n=59) compared with early (n=27) BCa (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Endo180 levels are elevated in the plasma of patients with metastatic compared with early BCa. Plasma samples from BCa patients (n=88) were resolved on 8% w/v SDS polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and immunoblot analysis was performed using 1 mg ml−1 mouse anti-human Endo180 monoclonal 39.10 antibody and 1/4000 dilution of horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (a representative blot is presented in Supplementary Figure 1). Relative plasma Endo180 levels were calculated from the mean measurement obtained from three analytical repeats. Plasma from the same early BCa patient was used as a reference control (relative Endo180 level=1.0) and the normalisation of densitometric measurements on all analytical gels. CA 15-3 antigen concentrations (U ml−1) were measured using a non-competitive two-step immunoassay in plasma samples (n=86a) collected in parallel. The box and whiskers plots shown depict the total range, interquartile distribution, outliers (open or closed circles) and median value (horizontal line) of relative plasma Endo180 levels (A, C) and plasma concentrations of CA 15-3 antigen (Log10 [U ml−1]) (B, D). (A) The graph compares relative plasma Endo180 levels in cases of early BCa (n=29) and metastatic BCa (n=59). (B) The graph compares plasma concentrations of CA 15-3 antigen (Log [U ml−1]) in cases of early BCa (n=27a) and metastatic BCa (n=59). (C) The graph compares relative plasma Endo180 levels in cases of early BCa (n=29) and recurrent locoregional disease (n=5) or metastasis in visceral tissue alone (n=12), bone alone (n=14) or bone with dissemination in lung (n=5), liver (n=8) or two or more visceral organs (n=15). (D) The graph compares plasma concentrations of CA 15-3 antigen (Log10 [U ml−1]) in cases of early BCa (n=27*) and metastatic sites as described above (C). The P-values shown were determined using Mann–Whitney U-test for comparison between cases of early BCa and metastatic BCa (A, B); or Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance for comparison between early BCa and recurrent/metastatic BCa stratified according to affected tissue sites (C, D), and confirmed by Bonferroni adjustment (P=0.05/n, n=7). aData for CA 15-3 antigen were missing for 2 out of the 29 early BCa patients included in the study.

Plasma Endo180 levels are increased in locoregional disease, visceral metastasis and bone metastasis

To investigate whether Endo180 was predictive of recurrent and/or metastatic disease in visceral and/or osseous tissue, the 59 recurrent/metastatic patients were stratified according to tissue site(s) affected by secondary lesions. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction (P=0.05/n, n=7) revealed that relative Endo180 levels were significantly different (P=0.0005) in early BCa (mean±s.d.: 0.92±0.37, n=29), recurrent locoregional disease (mean±s.d.: 1.53±0.46, n=5), metastases in one or more visceral tissues (mean±s.d.: 1.78±1.20, n=12), bone metastasis alone (mean±s.d.: 1.48±0.64, n=14) and bone metastasis with additional dissemination in lung(s) (mean±s.d.: 1.72±0.61, n=5), liver (mean±s.d.: 2.18±0.48, n=8) or ⩾2 visceral tissue sites (mean±s.d.: 1.71±1.09, n=15) (Figure 3C). Individual Mann–Whitney U-tests confirmed that relative Endo180 levels increased for all metastatic sites compared with early BCa (P<0.01). Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance conferred a trend towards significance between CA 15-3 antigen concentrations (U ml−1) in the same groups of patients (P<0.09) (Figure 3D).

Diagnostic accuracy of Endo180

The performance of Endo180 and CA 15-3 antigen, alone and in combination, for the classification of recurrent/metastatic vs early/localised BCa was assessed. The respective sensitivity (% true-positive rate) and specificity (% false-positive rate) for the classification of metastasis by CA 15-3 antigen alone (fixed cutoff: 28 U ml−1) (as used in the Department of Medical Oncology at Imperial College NHS Trust) was 85% and 50%. For a consecutive range of values for Endo180 alone (variable cutoff: 0.95–1.65 relative plasma levels), the respective range of true-positive and false-positive rates for the classification of metastasis was 82–97% and 36–54%. For CA 153 antigen (fixed cutoff: 28 U ml−1) combined with Endo180 (variable cutoff: 0.95–1.65 relative levels), the respective true-positive and false-positive rates for classification of metastasis was 94–97% and 32–48% (Supplementary Figure 2).

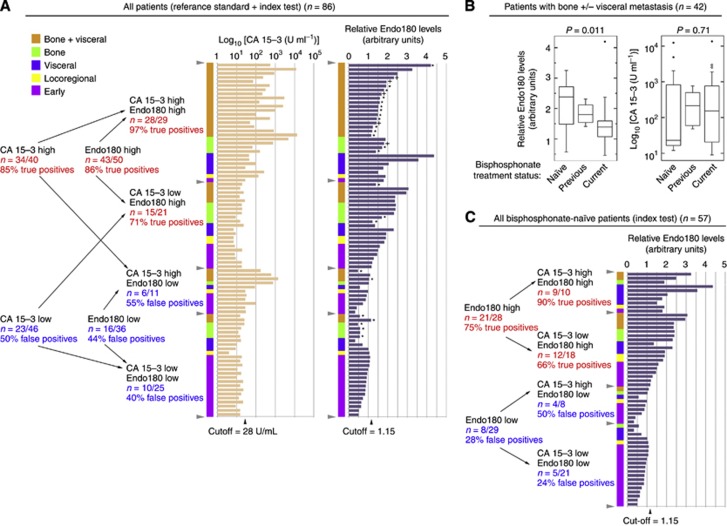

Modulation of Endo180 by bisphosphonates

Stratification of the 42 patients with bone metastasis (with or without additional visceral metastasis) according to bisphosphonate treatment status (Figure 4A) and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction (P=0.05/n, n=3) revealed that Endo180 levels were significantly higher in bisphosphonate-naive cases (mean±s.d.=2.17±0.79, n=13) compared with those having previous (mean±s.d.: 1.83±0.33, n=5) or current (mean±s.d.=1.37±0.74, n=24) bisphosphonate treatment (P=0.011) (Figure 4B). In contrast, CA 15-3 antigen levels were unaltered by bisphosphonates (P=0.71) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Endo180 improves the prediction of metastatic BCa in the bisphosphonate-naive setting. (A) Stratification of all patients for which the index test and reference standard test were performed (n=86a) according to low or high CA 15-3 antigen and Endo180 status with respective cutoffs of 28 U ml−1 and relative plasma level of 1.15 indicated with grey arrowheads. Disease status for each patient is indicated using the following colour code: early BCa (pink), locoregional disease (yellow), visceral metastasis alone (purple), bone metastasis alone (green) and bone plus visceral metastasis (orange). The sensitivity (% true positives) and specificity (% false negatives) of Endo180 and CA 15-3 antigen for classification of metastasis are indicated as fractional numbers of patients and corresponding percentages. Patients currently (*) or previously (+) receiving bisphosphonate treatment are indicated. Box and whiskers plots depicting the total range, interquartile distribution, outliers (open and closed circles) and median value (horizontal line) of: (B) Endo180 and CA 15-3 antigen; in the 42 patients with bone metastasis with or without visceral tissue metastasis classified as bisphosphonate naive (n=13), having previously received bisphosphonates (n=5) or currently being treated with bisphosphonates (n=24). The P-values shown were determined using Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA, and confirmed by Bonferroni adjustment (P=0.05/n, n=3). (C) Evaluation of the sensitivity (% true positives) and specificity (% false negatives) of Endo180 and CA 15-3 antigen in all 57 bisphosphonate-naive patients was conducted using the same criteria as used in (A). The Endo180 cutoff (1.15) chosen for the analyses presented in (A, C) was close to the Q1 value for recurrent/metastatic BCa (1.13) and the Q3 value for early BCa (1.13) and was higher than the upper 95% CI for early BCa (1.06). aData for CA 15-3 antigen were missing for 2 out of the 29 early BCa patients included in the study.

The true-positive and false-positive rates of 68% and 45% for CA 15-3 antigen (fixed cutoff: 28 U ml−1); 70–95% and 20–31% for Endo180 alone (variable cutoff: 0.95–1.65 relative levels); and 87–92% and 21–28% for Endo180 in combination with CA 15-3 antigen in bisphosphonate-naive cases (n=57) indicates that Endo180 improves the specificity for classifying metastasis where there is no current or prior exposure to these agents (Figure 4C).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that Endo180 has the potential to fulfil the official National Institutes of Health definition of a biomarker as a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention (Diamandis, 2010). The accuracy of Endo180 for the classification determined in this study is aligned with biomarker discoveries made by homing-in on aberrant collagen turnover in metastatic bone disease (Lipton et al, 2011) where Endo180 is proposed to play a fundamental role (Caley et al, 2011; Sturge et al, 2011). In addition, Endo180 also has a direct molecular (Behrendt et al, 2000) and functional (Sturge et al, 2003; Messaritou et al, 2009) relationship with urokinase-type plasminogen activator, which is currently recommended as a prognostic marker for recurrent/metastatic BCa (Harris et al, 2007; Cardoso et al, 2011).

CA 15-3 antigen is normally present on luminal epithelial cells lining breast ducts and its ectodomain is proteolytically cleaved by sheddases and membrane-type I matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) during metastasis (Thathiah et al, 2003; Thathiah and Carson, 2004). Interestingly a co-functional relationship between Endo180 and MT1-MMP has been reported in vivo (Wagenaar-Miller et al, 2007) and in vitro (Messaritou et al, 2009). Together with the observation that Endo180 and MT1-MMP are co-expressed on epithelial and stromal cells in primary tumours (Kogianni et al, 2009), this suggests that MT1-MMP could facilitate Endo180 release and that the cellular source of Endo180 is tumour and/or stromal in origin. These independent cellular mechanism(s) and/or sources may explain the weak linear correlation between Endo180 and CA 15-3 antigen (Supplementary Figure 3).

The elevated levels of Endo180 observed during locoregional recurrence, visceral metastasis and bone metastasis suggests that increased ectodomain shedding occurs when the disease becomes active at a range of tissue sites. However, for the diagnosis of early invasive cancer, the release of Endo180 from small asymptomatic tumours – either from the tumour cells themselves and/or their stromal microenvironment – will need to be detectable above background levels in the normal population. This could be feasible given that Endo180 participates in tumour cell and stromal cell collagen turnover in primary tumours and osteolytic metastases (Curino et al, 2005; Wienke et al, 2007; Caley et al, 2011), indicating that its release could be linked to bidirectional and heterotypic interactions between tumour and stromal cells. Since 25, out of the 29, BCa patients currently or previously receiving bisphosphonates had metastatic lesions in their visceral tissue, as well as bone, it is also feasible that bisphosphonates modulate Endo180 activity at non-bone sites.

The role of bisphosphonates as an adjuvant therapy has recently been explored in the ABCSG-12 (Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group 12) and AZURE (Adjuvant Treatment with Zoledronic Acid in Stage II/III Breast Cancer) trials. ABCSG-12 reported that addition of zoledronic to endocrine therapy reduced disease-free survival but not overall survival in premenopausal women with endocrine responsive BCa (Gnant et al, 2009, 2011). In the AZURE trial, zoledronic acid did not improve disease-free or overall survival but significantly reduced visceral metastases and locoregional recurrence in a low oestrogen environment (Coleman et al, 2011). Given the important role of Endo180 in collagen remodelling – and the demonstration here that Endo180 is suppressed by bisphosphonates – it is possible that the elevated activity of Endo180 at locoregional and visceral sites helps drive the bisphosphonate-sensitive mechanism identified in disseminated tumour cells (Solomayer et al, 2012); and/or adjacent stromal cells; in the collagen-rich microenvironments of primary and secondary tumours.

Prospective-sample-collection and retrospective-blinded-evaluation will be necessary to ascertain how Endo180 levels change as metastatic disease develops and progresses; and to validate whether Endo180 is an accurate diagnostic, screening or prognostic marker in metastatic BCa. The observation that Endo180 is suppressed by bisphosphonates suggests that it could be an indicator of response to bisphosphonates; and should be tested in the setting of metastatic bone disease for its prognostic accuracy in predicting skeletal-related events in correlation with bone-targeted treatment. In a broader context, Endo180 could also be considered as a generalised marker for metastatic disease in other solid tumours.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this study; Professor Gerry Thomas and the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, Human Biomaterials Resource Centre (Tissue Bank); Professor Clare M Isacke (Institute of Cancer Research, London) for Endo180 antibodies; Dr Richard Harvey (Department of Medical Oncology, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust) for CA 15-3 antigen measurement. The Division of Cancer at Imperial College London, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust is an Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre (ECMC) supported by funds from Cancer Research UK and the Department of Health (C37/A7283) and forms part of Imperial Cancer Research UK Centre (C42671/A12196). CP is recipient of a CRUK Clinician Scientist award. JW is The Flow Foundation Professor of Oncology at Imperial College London. MPC and GK were supported by donations from Tony and Rita Gallagher and Imperial College NHS Healthcare Trust Special Trustees (to JW and JS). MPC was funded by The Rosetrees Trust (Grant JS16/M59; to JW and JS). A-VF was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia fellowship (project supervisor: JS) and Imperial College NHS Healthcare Special Trustees (to JW and JS). MR-T was funded by the Association of International Cancer Research (Grant 08-0803 to JS).

Author contributions

JS conceived the study. CP recruited patients for inclusion in the study. JS, CP, MCP, A-VF and GK designed the experiments. A-VF and GK conducted cell line experiments. KP, LW, JO and KE collected and processed the samples. KP and MCP conducted the index test. MR-T performed epitope mapping. CP retrieved clinicopathological and treatment data. CP and JS cross-referenced data and performed the data analysis. JS, CP and JW discussed and interpreted the data. JS and CP wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary Material

References

- Behrendt N, Jensen ON, Engelholm LH, Mortz E, Mann M, Dano K (2000) A urokinase receptor-associated protein with specific collagen binding properties. J Biol Chem 275(3): 1993–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, Lijmer JG, Moher D, Rennie D, de Vet HC (2003) Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Clin Biochem 36(1): 2–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caley MP, Kogianni G, Adamarek A, Gronau J, Rodriguez-Teja M, Fonseca A-V, Mauri F, Sandison A, Rhim JS, Palmieri C, Cobb J, Waxman J, Sturge J (2011) TGFβ1-Endo180 dependent collagen deposition is dysregulated at the tumour-bone stromal interface in bone metastasis. J Path 226(5): 775–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso F, Fallowfield L, Costa A, Castiglione M, Senkus E (2011) Locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 22(Suppl 6): vi25–vi30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RE, Marshall H, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Burkinshaw R, Keane M, Gil M, Houston SJ, Grieve RJ, Barrett-Lee PJ, Ritchie D, Pugh J, Gaunt C, Rea U, Peterson J, Davies C, Hiley V, Gregory W, Bell R (2011) Breast-cancer adjuvant therapy with zoledronic acid. N Engl J Med 365(15): 1396–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curino AC, Engelholm LH, Yamada SS, Holmbeck K, Lund LR, Molinolo AA, Behrendt N, Nielsen BS, Bugge TH (2005) Intracellular collagen degradation mediated by uPARAP/Endo180 is a major pathway of extracellular matrix turnover during malignancy. J Cell Biol 169(6): 977–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamandis EP (2010) Cancer biomarkers: can we turn recent failures into success? J Natl Cancer Inst 102(19): 1462–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MJ, Evoy D, McDermott EW (2010) CA 15-3: uses and limitation as a biomarker for breast cancer. Clin Chim Acta 411(23-24): 1869–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 127(12): 2893–2917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Schippinger W, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, Postlberger S, Menzel C, Jakesz R, Seifert M, Hubalek M, Bjelic-Radisic V, Samonigg H, Tausch C, Eidtmann H, Steger G, Kwasny W, Dubsky P, Fridrik M, Fitzal F, Stierer M, Rucklinger E, Greil R, Marth C (2009) Endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 360(7): 679–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Stoeger H, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, Heck D, Menzel C, Jakesz R, Seifert M, Hubalek M, Pristauz G, Bauernhofer T, Eidtmann H, Eiermann W, Steger G, Kwasny W, Dubsky P, Hochreiner G, Forsthuber EP, Fesl C, Greil R (2011) Adjuvant endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: 62-month follow-up from the ABCSG-12 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 12(7): 631–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, Norton L, Ravdin P, Taube S, Somerfield MR, Hayes DF, Bast RC (2007) American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25(33): 5287–5312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijbers IJ, Iravani M, Popov S, Robertson D, Al-Sarraj S, Jones C, Isacke CM (2010) A role for fibrillar collagen deposition and the collagen internalization receptor Endo180 in glioma invasion. PLoS One 5(3): e9808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogianni G, Walker MM, Waxman J, Sturge J (2009) Endo180 expression with cofunctional partners MT1-MMP and uPAR-uPA is correlated with prostate cancer progression. Eur J Cancer 45(4): 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton A, Chapman JA, Demers L, Shepherd LE, Han L, Wilson CF, Pritchard KI, Leitzel KE, Ali SM, Pollak M (2011) Elevated bone turnover predicts for bone metastasis in postmenopausal breast cancer: results of NCIC CTG MA.14. J Clin Oncol 29(27): 3605–3610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaritou G, East L, Roghi C, Isacke CM, Yarwood H (2009) Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase activity is regulated by the endocytic collagen receptor Endo180. J Cell Sci 122(Part 22): 4042–4048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt PM, Potter JD (2008) Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(20): 1432–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Pan HC, Clarke M, Cutter D, Darby S, McGale P, Taylor C, Wang YC, Bergh J, Di Leo A, Albain K, Swain S, Piccart M, Pritchard K (2012) Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet 379(9814): 432–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomayer EF, Gebauer G, Hirnle P, Janni W, Luck HJ, Becker S, Huober J, Kramer B, Wackwitz B, Wallwiener D, Fehm T (2012) Influence of zoledronic acid on disseminated tumor cells in primary breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 23(9): 2271–2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge J, Caley MP, Waxman J (2011) Bone metastasis in prostate cancer: emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8(6): 357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge J, Todd SK, Kogianni G, McCarthy A, Isacke CM (2007) Mannose receptor regulation of macrophage cell migration. J Leukocyte Biol 82(3): 585–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge J, Wienke D, East L, Jones GE, Isacke CM (2003) GPI-anchored uPAR requires Endo180 for rapid directional sensing during chemotaxis. J Cell Biol 162(5): 789–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge J, Wienke D, Isacke CM (2006) Endosomes generate localized Rho-ROCK-MLC2-based contractile signals via Endo180 to promote adhesion disassembly. J Cell Biol 175(2): 337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulek J, Wagenaar-Miller RA, Shireman J, Molinolo A, Madsen DH, Engelholm LH, Behrendt N, Bugge TH (2007) Increased expression of the collagen internalization receptor uPARAP/Endo180 in the stroma of head and neck cancer. J Histochem Cytochem 55(4): 347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, Blobel CP, Carson DD (2003) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme/ADAM 17 mediates MUC1 shedding. J Biol Chem 278(5): 3386–3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, Carson DD (2004) MT1-MMP mediates MUC1 shedding independent of TACE/ADAM17. Biochem J 382(Part 1): 363–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar-Miller RA, Engelholm LH, Gavard J, Yamada SS, Gutkind JS, Behrendt N, Bugge TH, Holmbeck K (2007) Complementary roles of intracellular and pericellular collagen degradation pathways in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 27(18): 6309–6322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienke D, Davies GC, Johnson DA, Sturge J, Lambros MB, Savage K, Elsheikh SE, Green AR, Ellis IO, Robertson D, Reis-Filho JS, Isacke CM (2007) The collagen receptor Endo180 (CD280) is expressed on basal-like breast tumor cells and promotes tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res 67(21): 10230–10240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienke D, MacFadyen JR, Isacke CM (2003) Identification and characterization of the endocytic transmembrane glycoprotein Endo180 as a novel collagen receptor. Mol Biol Cell 14(9): 3592–3604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.