Abstract

Background:

To evaluate surgical outcome and survival benefit after quaternary cytoreduction (QC) in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) relapse.

Methods:

We systematically evaluated all consecutive patients undergoing QC in our institution over a 12-year period (October 2000–January 2012). All relevant surgical and clinical outcome parameters were systematically assessed.

Results:

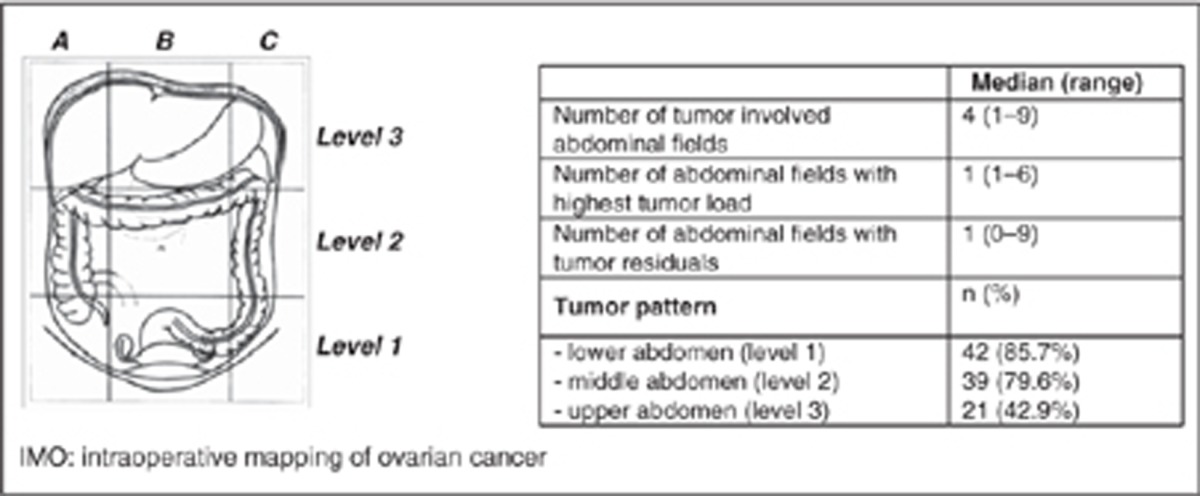

Forty-nine EOC patients (median age: 57; range: 28–76) underwent QC; in a median of 16 months (range:2–142) after previous chemotherapy. The majority of the patients had an initial FIGO stage III (67.3%), peritoneal carcinomatosis (77.6%) and no ascites (67.3%). At QC, patients presented following tumour pattern: lower abdomen 85.7% middle abdomen 79.6% and upper abdomen 42.9%. Median duration of surgery was 292 min (range: a total macroscopic tumour clearance could be achieved. Rates of major operative morbidity and 30-day mortality were 28.6% and 2%, respectively.

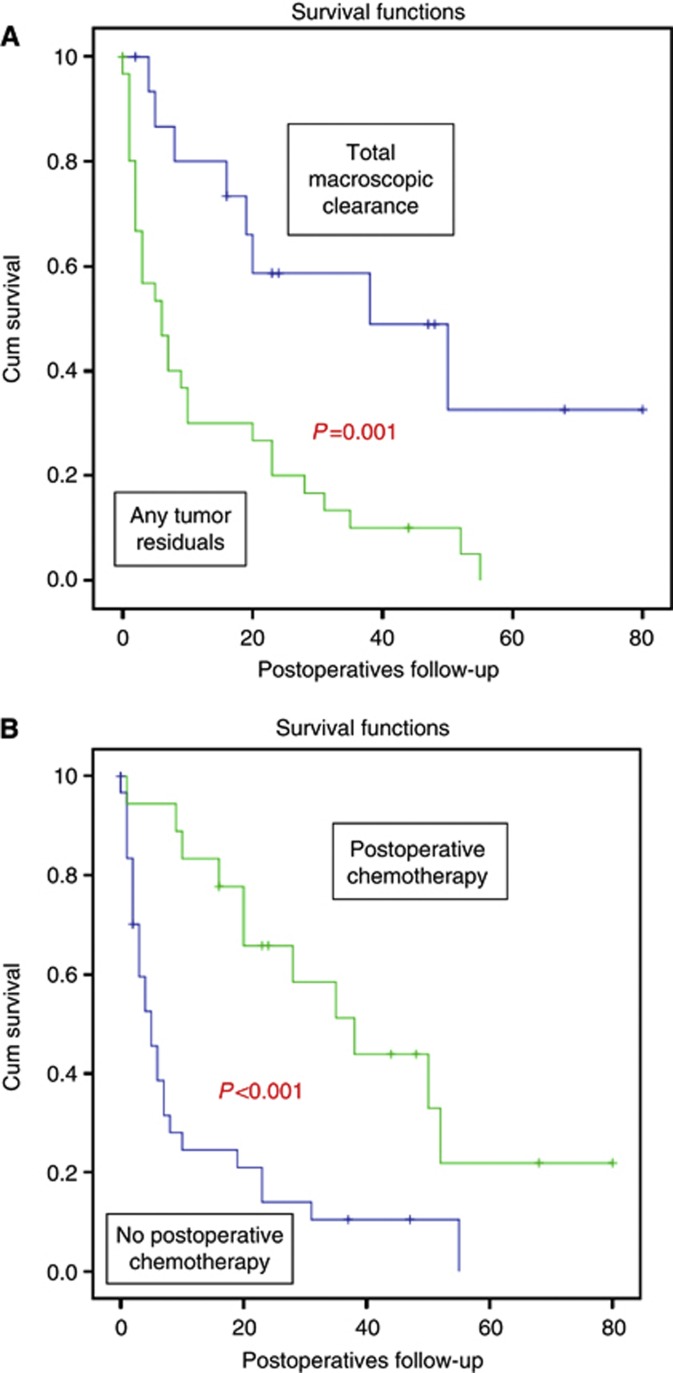

Mean follow-up from QC was 18.41 months (95% confidence interval (CI):12.64–24.18) and mean overall survival (OS) 23.05 months (95% CI: 15.5–30.6). Mean OS for patients without vs any tumour residuals was 43 months (95% CI: 26.4–59.5) vs 13.4 months (95% CI: 7.42–19.4); P=0.001. Mean OS for patients who received postoperative chemotherapy (n=18; 36.7%) vs those who did not was 40.5 months (95% CI: 27.4–53.6) vs 12.03 months (95% CI: 5.9–18.18); P<0.001.

Multivariate analysis indentified multifocal tumour dissemination to be of predictive significance for incomplete tumour resection, higher operative morbidity and lower survival, while systemic chemotherapy subsequent to QC had a protective significant impact on OS. No prognostic impact had ascites, platinum resistance, high grading and advanced age.

Conclusion:

Even in this highly advanced setting of the third EOC relapse, maximal therapeutic effort combining optimal surgery and chemotherapy appear to significantly prolong survival in a selected patients ‘group’.

Keywords: ovarian cancer relapse, quaternary cytoreduction, overall survival, morbidity, tumour dissemination

The knowledge around epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), a rare but most often fatal ending disease, has been constantly increasing over the last decades. Novel theories and discoveries about its true origin and its special histopathological features have shed light into the actual nature and behaviour of EOC, aiming to set the basis for an optimal therapeutic management of the affected patients (Singer et al, 2002; Shih and Kurman, 2004; Shih and Kurman, 2005; Kurman and Shih, 2008; Vang et al, 2009; Kurman and Shih, 2010).

Even though many questions remained to be answered in the future, such as the optimal timing of primary debulking, the therapeutic benefit of targeted agents and most importantly putative mechanisms of early detection or even prevention of the disease, the value of optimal tumour resection defined by the amount of postoperative residual disease has well been established in numerous prospective and retrospective analyses for the primary situation of the disease (Bristow, 2000; Chi et al, 2004; du Bois et al, 2005; Kurman et al, 2008; Zivanovic et al, 2008; du Bois et al, 2009; Fanfani et al, 2010). Complete tumour resection outranks prognostically other unfavourable factors such as peritoneal carcinomatosis or even advanced FIGO stage (Aletti et al, 2009; Harter et al, 2009; Wimberger et al, 2010).

Various authors have attempted to define the role of surgery in the relapsed setting of the disease. Numerous analyses mainly of retrospective design could show a benefit of patients who underwent complete secondary or even tertiary cytoreduction (Leitao et al, 2004; Pfisterer et al, 2005; Chi et al, 2006; Harter et al, 2006; Karam et al, 2007; Gultekin et al, 2008; Schorge et al, 2010; Shih et al, 2010a; Fotopoulou et al, 2011a; Hızlı et al, 2012). Two multicenter, prospective randomised trials, one of the AGO German group (DESKTOP III) and one of the American GOG (GOG 213) are ongoing randomising EOC patients to secondary cytoreduction and subsequent second-line chemotherapy or second-line chemotherapy alone. The results of these trials will reliably define the final role of high-quality surgery in the first relapse of the ovarian cancer disease and change the global standard of treatment.

Data about quaternary cytoreductive surgery are, however, very scarce. To our knowledge only one single monocentric analysis exists so far including 15 patients who underwent quaternary surgery treated in the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (Shih et al, 2010). This study was conducted to evaluate the impact of quaternary cytoreduction (QC) on overall survival (OS) of patients with recurrent EOC. We analysed the surgical outcome including operative morbidity and mortality, identified independent predictors of complete tumour resection and described the intraoperative tumour dissemination patterns followed in the third-OC relapse as defined by a validated intraoperative documentation tool for ovarian cancer mapping.

Materials and methods

A systematic evaluation was performed to assess the intraoperative tumour dissemination pattern, the surgical procedures performed as well as the operative morbidity and mortality for all consecutive women, undergoing quaternary surgical cytoreduction in the Department of Gynaecology at the Charité, Campus Virchow Clinic between October 2000 and January 2012. Quaternary surgery was defined as the fourth surgical cytoreductive attempt due to the third or higher histologically proven ovarian cancer relapse (i.e., primary, secondary, tertiary and QC). Staging at primary operation was defined in accordance with the FIGO criteria for epithelial ovarian carcinoma (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: Changing in definitions of clinical staging for carcinoma of the cervix and ovary, 1987).

All operations were performed through midline laparotomy by one of four gynaecologic oncologic surgeons in cooperation within a multidisciplinary surgical team to achieve radicality through a multivisceral approach. Primary aim was maximal tumour reduction in an elective setting for symptomatic but resectable recurrence and/or to achieve palliation in situations like bowel obstruction, bleeding or pain in the minority of the cases. However, even in the palliative emergency setting, all patients were operated also in terms of en-bloc resections, and removal of large parts of the tumour together with the obstructed small or large bowel. Main reason for that was that in this quaternary setting a simple surgery, such as merely ileostomy or colostomy was not feasible due to the massive adhesions, which in combination with the peritoneal carcinosis or even peritonitis made any simple dissection impossible. For that reason, surgical effort was in these patients equal if not higher compared with the elective surgeries and we performed all dissections in terms of an extraperitoneal, en-bloc preparation. Patients who presented with ascites and/or diffuse tumour dissemination in imaging modalities and without symptoms, which made an operative intervention inevitable, were not operated but received a systemic treatment.

In every patient, the detailed tumour pattern was intraoperatively assessed by an independent trained person as based on the surgical procedures performed and by a systematic interview of the surgical team. Postoperatively all histological findings and collected data were entered into a validated documentation system (intraoperative mapping of ovarian cancer (IMO)), especially developed for ovarian neoplasms with special focus on the description of the tumour pattern, maximal tumour burden, postoperative tumour residuals and the amount of preoperative ascites. All further relevant patients’ data including history, follow-up and survival data were abstracted from the individual patients’ records.

Intraoperative mapping of ovarian cancer

Intraoperative mapping of ovarian cancer represents a detailed and objective surgical and histopathological documentation system validated to obtain an objective description of the ovarian tumour spread within the abdominal cavity, both in primary and recurrent situations and to define more precisely the histopathological features of the malignancy (Sehouli et al, 2003; Sehouli et al, 2009; Fotopoulou et al, 2011b; Braicu et al, 2012). Three ‘IMO levels’ divide the abdomen into three spaces: lower (level 1), middle (level 2) and upper (level 3) abdomen (Table 2). Nine ‘IMO fields’, three at each level, provide a subclassification of the peritoneal cavity aiming at a more precise documentation of the tumour dissemination pattern. The patients’ informed consent was always given before surgery and sample collection and documentation.

Follow-up

Patients were regularly evaluated at the end of the treatment for evidence of a new disease recurrence. Clinical examinations, transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound, CA125 (if the preoperative value was elevated) assays were performed every 3 months. A CT/MRI scan was ordered if the above examinations revealed any pathology. Isolated CA125 increase was not regarded as a recurrence.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., 233S. Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL, USA). The Fisher’s exact test and Kendall’s tau-b were used for the univariate analysis, where appropriate. Crude and adjusted odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were obtained using logistic regression analysis. Estimates of survival were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank tests were used for univariate statistical comparisons. The relative importance of variables as independent predictors of OS was analysed with the multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for prognostic factors were estimated. All significances reported were two-tailed at a level of 0.05. The follow-up time was calculated starting on the day of surgery.

Results

A total of 49 patients who underwent quaternary surgery in our institution were identified. The total number of operations conducted at the same time due to primary malignant lesions of the ovary/peritoneum or fallopian tube of any stage was 1029 and 743 for ovarian cancer relapse of any line. In eight (16.3%) patients quaternary surgery was performed after the fourth relapse, whereas in four (8.2%) patients quaternary surgery was even performed after the fifth relapse. In all, 70% of the patients underwent QC between 3 and 10 years after primary diagnosis of the malignant disease with a median of 16 months (range: 2–142) after previous chemotherapy. Forty-four (89.8%) patients had a first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (i.e., paclitaxel plus carboplatin or carboplatin plus cyclophosphamide). Thirty-one patients (63.3%) were initially platinum sensitive. Only 13 patients (26.5%) received platinum as third- or fourth-line chemotherapy before quaternary surgery. The vast majority of the patients (67.3%) had a FIGO III tumour stage. Although >90% of the patients had no or <500 ml ascites, 38 patients (77.6%) presented a peritoneal carcinomatosis at quaternary surgery. Relevant patients- and tumour-related characteristics are presented in Table 1. Only 4 (8%) patients were operated in an acute emergency setting due to bowel obstruction or perforation, the other 45 patients (92%) were operated in an elective setting due to symptomatic but potentially resectable disease.

Table 1. Patients, tumour-related and surgical characteristics of the 49 patients who underwent QC due to EOC relapse.

| Variables | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| N | 49 |

| Median age at surgery (years) | 57 (28–76) |

|

FIGO stage at primary diagnosis

| |

| I | 6 (12.2%) |

| II | 6 (12.2%) |

| III | 33 (67.3%) |

| IV | 1 (2.04%) |

| Histology | |

| Serous-papillary | 33 (67.3%) |

| Mucinous | 1 (2%) |

| Endometriod | 12 (24.5%) |

| Clear cell | 3 (6.1%) |

|

Intraoperative ascites

| |

| None | 33(67.3%) |

| <500 ml | 12 (24.5%) |

| ⩾500 ml | 2 (4.1%) |

|

Grading

| |

| G1 | 3 (6.1%) |

| G2 | 11 (22.4%) |

| G3 | 29 (59.2%) |

|

Median CA125 (U/ml)

| |

| Preoperative | 736 (28–2843) |

| After 3 cycles of chemotherapy | 220 (19–365) |

| After chemotherapy completion | 84 (21–156) |

|

Postoperative tumor residuals

| |

| None | 16 (32.6%) |

| ⩽0.5 cm | 15 (30.6%) |

| 0.5–1 cm | 9 (18.3%) |

| >1 cm | 9 (18.3%) |

|

Years after primary diagnosis

| |

| 2–3 years | 3 (6.1%) |

| 3–5 years | 20 (40.8%) |

| 5–10 year | 14 (28.5%) |

| >10years | 12 (24.5) |

|

Lymph nodes affected

| |

| N0 | 4 (8.2%) |

| N1 | 14 (28.6%) |

| Nx | 31 (63.3%) |

|

Operative procedure

| |

| Peritonectomy | 21 (42.9%) |

| Pelvic LND | 2 (4.1%) |

| Paraaortic LND | 5 (10.2%) |

| Peritonectomy | 21 (43%) |

| Partial liver resection | 3 (6.1%) |

| Liver capsule resection | 1 (2%) |

| Small bowel resection | 25 (51%) |

| Large bowel resection | 21 (42.9%) |

| Partial gastrectomy | 1 (2%) |

| Ileostomy | 10 (20.4%) |

| Colostomy | 6 (12.2%) |

| Cholecystectomy | 2 (4.1%) |

| Splenectomy | 2 (4.1%) |

| Diaphragmatic resection | 1 (2.0%) |

|

Operative morbidity and mortality

| |

| Any major operative complication | 14 (28.6%) |

|

Major complications

| |

| Anastomotic insufficiency | 3 (6.1%) |

| Postoperative fistula formation | 1 (2%) |

| Thromboembolic event | 1 (2%) |

| Infection/sepsis | 9 (18.4%) |

| Postoperative haemorhage | 4 (8.2%) |

|

Symptomatic thrombosis/embolism

| |

| Short bowel syndrome | 1 (2%) |

| Bowel obstruction | 1 (2%) |

| Pneumonia/Pleura effusion | 6 (12.2%) |

| Multiorgan failure | 2 (4.1%) |

| 30-days mortality | 1 (2%) |

Abbreviations: EOC=epithelial ovarian cancer; FIGO=International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; LND=lymph node dissection; QC=quaternary cytoreduction.

Median duration of surgery was 292 min (range: 62–670 min). In 32.6% of the patients a total macroscopic tumour clearance could be obtained (Table 1). More than 80% of the patients had a tumour involvement of the middle and lower abdomen. Detailed tumour dissemination patterns are presented in Table 2. Following anatomic structures were affected with tumour: large bowel 34 (69.4%), small intestine 30 (61.2%), mesentery 24 (49%), pelvic side wall 22 (44.9%), abdominal wall 21 (42.9%), pouch of douglas/vaginal cuff 15 (30.6%), diaphragm 11 (22.4%), omentum 10 (20.4%), liver/liver capsule 8 (16.3%), greater curvature of stomach 5 (10.2%) and spleen 5 (10.2%).

Table 2. Intraoperative tumour dissemination pattern and fields of higher tumour load and tumour residuals according to intraoperative mapping of ovarian cancer.

In the vast majority of the patients a multivisceral surgical approach was required to achieve optimal tumour resection. All surgical procedures performed are presented in Table 1. Median number of performed intestinal resections was 1 (range: 0–4) with median numbers of intestinal anastomoses of 1 (range: 0–4). In up to 10% of the patients bulky lymph nodes had to be removed; with median number of removed pelvic and paraaortic lymph nodes of 3 (range: 1–11) and 5 (range: 1–23), respectively. Rates of major operative morbidity and 30-day mortality were 28.6% and 2%, respectively. Details are presented in Table 1.

Within a mean follow-up time of 18.41 months (95% CI: 12.64–24.18), 38 patients (77.6%) have died. No autopsy was performed in any of the cases, but clinically all patients died due to tumour progression or tumour-related complications.

Mean PFS for the entire patient population was 22.5 months (95% CI: 13.6–32.2). In a patients population where 32.6% of the patients underwent total macroscopic clearance, mean OS was 23.05 months (95% CI: 15.5–30.6) and median OS was 10 months (95% CI: 0.1–22 months).

When stratifying the patients according to their postoperative tumour residuals, then patients who underwent a total macroscopic tumour clearance had with a mean OS of 43 months (95% CI: 26.4–59.5) a highly significantly better outcome (P=0.001) than those patients with any tumour residuals who presented mean OS rates of 13.4 months (95% CI: 7.42–19.4). Survival curves are presented in Figure 1. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in OS between patients operated due to the third or more than the third relapse (P=0.42).

Figure 1.

Survival curves of ovarian cancer patients after quaternary debulking surgery according to (A) postoperative tumour residuals and (B) the application of postoperative systemic chemotherapy.

Thirty-one patients (63.3%) did not receive any subsequent systemic chemotherapy after quaternary surgery. The reasons were as follows: 1 (2%) patient died, 23 (47%) patients refused any systemic treatment and 7 (14.2%) patients were too weak to receive any chemotherapy. Mean OS was for those patients who received postoperative adjuvant treatment significantly higher compared with patients who did not receive any chemotherapy (40.5 months; 95% CI: 27.4–53.6 vs 12.03 months; 95% CI: 5.9–18.18, respectively; P<0.001). Survival curves are presented also in Figure 1. The reasons for not receiving a postoperative chemotherapy were not assessed.

Univariate analysis identified only incomplete tumour resection (P=0.001), multifocal tumour dissemination (P=0.001; i.e., >4 IMO fields involved with tumour) and no chemotherapy after quaternary surgery (P<0.001) as having a negative significant impact on OS. No significant impact on OS appeared to have: age >65 years (P=0.32), ascites (P=0.45), extrapelvic tumour involvement (P=0.24), grading (P=0.16), FIGO IIIc/IV vs lower (P=0.8) and initial platinum response (P=0.67).

However, in multivariate analysis, tumour residuals failed to retain any prognostic significance for OS and only multifocal tumour dissemination, defined as >4 IMO fields affected with tumour, was identified to negatively affect OS. Systemic chemotherapy subsequent to quaternary surgery was shown to have a significant protective impact on OS (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis for OS, postoperative tumour residuals and operative morbidity after quaternary in EOC relapse.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P -value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

OSa

| |||

| Postoperative chemotherapy (yes vs no)b | 0.29 | 0.13–0.65 | 0.003 |

| Multifocal tumour dissemination (>4 vs ⩽4 number of tumour affected IMO fields) | 3.14 | 1.43–6.9 | 0.004 |

|

Postoperative tumour residualsc

| |||

| Multifocal tumour dissemination (>4 vs ⩽4 number of tumour affected IMO fields) | 11.5 | 1.17–112.4 | 0.036 |

|

Operative morbidityd

| |||

| Limited tumour dissemination (⩽4 vs >4 number of tumour affected IMO fields)b | 0.082 | 0.011–0.61 | 0.015 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; EOC=epithelial ovarian cancer; HR=hazard ratio; IMO=intraoperative mapping of ovarian cancer; OS=overall survival.

Not significant: grading; G3 vs G1/G2 (P=0.09); ascites: <500 ml vs ⩾500 ml (P=0.41); tumour residuals: none vs any (P=0.65); extrapelvic tumour involvement: yes vs no (P=0.79) and age: <65 vs > 65 years (P=0.49).

Protective.

Not significant; grading: G3 vs G1/G2 (P=0.37); platinum sensitivity: yes vs no (P=0.46) and extrapelvic tumour involvement: yes vs no (P=0.55).

Not significant; grading: G3 vs G1/G2 (P=0.58); extrapelvic tumour involvement: yes vs no (P=0.108), platinum sensitivity: yes vs no (P=0.16) and age: <65 vs >65 years (P=0.99).

In univariate analysis no factors could be identified to significantly affect PFS: advanced age >65 years (P=0.10), ascites >500 ml (P=0.60), tumour residuals (P=0.25), >4 IMO fields of tumour involvement (P=0.34), extrapelvic tumour involvement (P=0.664), initial advanced FIGO stage IIIc or IV (P=0.83), high grading (P=0.17) and platinum responder after first-line chemotherapy (0.78).

Multivariate analysis identified only limited tumour pattern, defined as 4 or less IMO fields being involved with tumour, to be protective against surgical morbidity (HR=0.082; 95% CI: 0.011–0.61; P=0.015). Also multifocal tumour dissemination, defined as >4 tumour affected IMO fields, was identified to have an independent significant risk of incomplete tumour resection (HR=11.5; 95% CI: 1.17–112.4; P=0.036). Other factors such as high grading, ascites >500 ml, postoperative tumour residuals, extrapelvic tumour involvement, platinum sensitivity and advanced age >65 years failed to reveal any independent significant impact. Detailed multivariate analysis data are presented in Table 3.

When evaluating separately only the four patients who were operated in a nonelective setting due to bowel obstruction (n=3) or intestinal perforation (n=1); then median OS was only 5 months (range: 0.1–11 months). The one patient with perforation died on the twentieth postoperative day and all other patients developed at least one major complication such as abscess formation or impaired wound healing. None of the patients could be operated completely tumour free, but in two of the four patients postoperative residual disease was <1 cm. One of these four patients managed to receive a postoperative systemic treatment.

Discussion

The present systematic evaluation represents the largest analysis of cytoreductive surgical effort beyond the tertiary cytoreduction so far. We could show that even in this highly palliative situation of the fourth or higher EOC relapse postoperative residual tumour and multimodality of treatment in terms of postoperative systemic chemotherapy were associated with a significant prolongation of survival. These findings are congruent to the well-established experiences already reported for the primary, secondary or even tertiary cytoreduction against EOC; where maximal surgical effort, reflected in minimal postoperative residual disease, was translated in a significant survival benefit (Gadducci et al, 2000; Leitao et al, 2004; Pfisterer et al, 2005; Chi et al, 2006; Harter et al, 2006; Benedetti et al, 2007; Karam et al, 2007; Gultekin et al, 2008; Schorge et al, 2010; Shih et al, 2010a; Fotopoulou et al, 2011a; Hızlı et al, 2012). Despite the extensive tumour dissemination with almost half of the patients carrying tumour load in the upper abdomen and more than two-thirds of the patients presenting peritoneal carcinomatosis, we could achieve an optimal tumour reduction in >60% of the patients. This underlines the value of high-quality surgery performed in specialised centres with adequate infrastructure and experience (Aletti et al, 2009). The fact that tumour residual disease failed to retain any prognostic significance for survival in multivariate analysis may be attributed to the small number of patients, where multifactorial multivariate analysis has to be interpreted with caution.

Interestingly, other factors with well-established prognostic value such as ascites, peritoneal carcinomatosis, platinum resistance, high grading and extrapelvic tumour involvement failed to retain any prognostic significance for this quaternary setting. Moreover, we found that survival was not significantly different between patients operated due to the third or higher number for relapses. The factor ‘platinum resistance’, which nowadays constitutes an almost restrictive factor against secondary cytoreduction, does not appear to have any role in the quaternary setting. This may be explained by the high selection process of the surgical candidates.

Two years ago Shih et al (2010b) published the first monocentric experience with quaternary surgery for EOC relapse including the limited number of 15 patients. Their findings showed remarkable equivalence to ours: the number of sites of recurrence and optimal tumour debulking were associated with a prolonged survival, especially when a total macroscopic tumour clearance could be obtained. In context with our data they also reported that all other well-established predictive factors for primary ovarian cancer and first relapse such as time to recurrence and response to platinum failed to retain any prognostic value on survival. This paradigm shift that appears to occur in terms of loss of value of conventional prognostic and predictive factors is not new. In all six so far existing studies evaluating tertiary cytoreduction in EOC, there is clear evidence that otherwise established common clinical factors were not able to adequately predict surgical outcome after tertiary surgery (Leitao et al, 2004; Karam et al, 2007; Gultekin et al, 2008; Shih et al, 2010a; Fotopoulou et al, 2011a; Hızlı et al, 2012). This is probably attributed to the high patients’ selection that inevitably occurs in these advanced settings. In contrast to the initial onset of EOC where all patients undergo surgery, even of variable quality and effort, candidates for secondary and even more for tertiary surgery are mostly being carefully selected, so that selection bias interfere with any prognostic analyses. A major drawback of most evaluations of relapse surgeries is the retrospective and not systematic character of data assessment, resulting in complete lack of transparency of the indications for surgery and of the criteria used to select the optimal candidates. An ongoing open prospective randomised trial of the German AGO group, the DESKTOP III, aims to prospectively validate for the first time the AGO score for identification of the ‘optimal’ candidates for secondary cytoreduction, who would benefit from a surgical approach. A further prospectively randomised trial of the GOG group (GOG 213) bring the entire concept even a step forward by additionally testing the value of bevacizumab in the secondary setting: patients are stratified to whether or not they are surgical candidates. If patients are deemed to be surgical candidates they are randomised to surgery or no surgery followed by randomisation to chemotherapy. If patients are randomised to no surgery they are subsequently randomised to carboplatin and paclitaxel or carboplatin/paclitaxel and bevacizumab.

We report of major operative morbidity rates similar to the 20% reported by Shih et al (2010b). When we evaluate this under the perspective of heavy pretreatment, including multiple prior cytotoxic therapies and multiple surgeries, it cannot be regarded as unexpectedly high. A relevant point of attention is, however, that both centres represent highly specialised, reference centres for ovarian cancer surgery, emphasising once more the tight association of surgical excellence and low operative morbidity (Aletti et al, 2009).

A further highly important finding of this analysis is the significant impact of postoperative systemic chemotherapy on OS. Even though this may constitute a selection bias as those patients who were fit enough to tolerate chemotherapy following radical surgery may anyway have a more favourable survival compared with those patients who were too weak to tolerate any systemic treatment, our findings underline the importance of combinative systemic and surgical treatment in the fight against EOC even in this advanced setting. These results are similar to those recently reported by the authors of the largest multicenter, international analysis of tertiary surgery evaluating >400 EOC patients (Fotopoulou et al, 2012), where the patients cohort that underwent postoperative systemic chemotherapy had a highly significant better survival compared with those patients who, for any reason, did not receive any systemic treatment.

Concluding, we could show that total macroscopic tumour clearance at quaternary surgery combined with systemic chemotherapy was clearly associated with a significant prolongation of survival in patients with the third or higher EOC relapse. Even though our analysis is monocentric, nonrandomised, observational and with limited number of patients, our data support a maximal therapeutic effort in this highly selected patients group. Also, despite the fact that prospective randomised trials to validate the impact of quaternary surgery will never be feasible, a universal nihilistic approach based on the palliative nature of the malignant disease cannot be always justified. It appears that maximal surgical effort aiming at optimal tumour reduction remains of high value throughout the entire natural course of EOC, from the primary to secondary, tertiary and even quaternary setting. Future larger multicenter, prospectively assessed evaluations are warranted to validate the present findings.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aletti GD, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, Jones MB, Stanhope RC, Wilson TO, Podratz KC, Cliby WA (2009) Quality improvement in the surgical approach to advanced ovarian cancer: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Coll Surg 208(4): 614–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti P, De Vivo A, Bellati F, Manci N, Perniola G, Basile S, Muzii L, Angioli R (2007) Secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 14(3): 1136–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braicu EI, Sehouli J, Richter R, Pietzner K, Lichtenegger W, Fotopoulou C (2012) Primary vs secondary cytoreduction for epithelial ovarian cancer: a paired analysis of tumor pattern and surgical outcome. Eur J Cancer 48(5): 687–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow RE (2000) Surgical standards in the management of ovarian cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 12(5): 474–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi DS, Franklin CC, Levine DA, Akselrod F, Sabbatini P, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo R, Poynor EA, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR (2004) Improved optimal cytoreduction rates for stages IIIC and IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer: a change in surgical approach. Gynecol Oncol 94(3): 650–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, Huh J, Schwabenbauer S, Hummer AJ, Venkatraman ES, Aghajanian C, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR (2006) Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 106(9): 1933–1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi DS, Franklin CC, Levine DA, Akselrod F, Sabbatini P, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo R, Poynor EA, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR (2004) Improved optimal cytoreduction rates for stages IIIC and IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer: a change in surgical approach. Gynecol Oncol 94: 650–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Bois A, Quinn M, Thigpen T, Vermorken J, Avall-Lundqvist E, Bookman M, Bowtell D, Brady M, Casado A, Cervantes A, Eisenhauer E, Friedlaender M, Fujiwara K, Grenman S, Guastalla JP, Harper P, Hogberg T, Kaye S, Kitchener H, Kristensen G, Mannel R, Meier W, Miller B, Neijt JP, Oza A, Ozols R, Parmar M, Pecorelli S, Pfisterer J, Poveda A, Provencher D, Pujade-Lauraine E, Randall M, Rochon J, Rustin G, Sagae S, Stehman F, Stuart G, Trimble E, Vasey P, Vergote I, Verheijen R, Wagner U Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup; AGO-OVAR; ANZGOG; EORTC; GEICO; GINECO; GOG; JGOG; MRC/NCRI; NCIC-CTG; NCI-US; NSGO; RTOG; SGCTG; IGCS; Organizational team of the two prior International OCCC (2005) 2004 Consensus statements on the management of ovarian cancer: final document of the 3rd International Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference (GCIG OCCC 2004). Ann Oncol 16(Suppl 8): viii7–viii12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray-Coquard I, Pfisterer J (2009) Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l'Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer 115(6): 1234–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Gallotta V, Ercoli A, Pacelli F, Costantini B, Vizzielli G, Margariti PA, Garganese G, Scambia G (2010) Upper abdominal surgery in advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer: role of diaphragmatic surgery. Gynecol Oncol 116(3): 497–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou C, Richter R, Braicu IE, Schmidt SC, Neuhaus P, Lichtenegger W, Sehouli J (2011a) Clinical outcome of tertiary surgical cytoreduction in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 18: 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou C, Rolf Richter R, Elena-Ioana Braicu E-I, Kuhberg M, Feldheiser A, Schefold JC, Lichtenegger W, Sehouli J (2011b) Impact of obesity on operative morbidity and clinical outcome in primary epithelial ovarian cancer after optimal primary tumor debulking. Ann Surg Oncol 18(9): 2629–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou C, Zang R, Gultekin M, Cibula D, Ayhan A, Liu D, Richter R, Braicu I, Mahner S, Harter P, Trillsch F, Kumar S, Peiretti M, Dowdy SC, Maggioni A, Trope C, Jalid S (2012) Value of tertiary cytoreductive surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer: an international multicenter evaluation. Ann Surg Oncol; e-pub ahead of print September 2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gadducci A, Iacconi P, Cosio S, Fanucchi A, Cristofani R, Riccardo Genazzani A (2000) Complete salvage surgical cytoreduction improves further survival of patients with late recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 79: 344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gultekin M, Velipaşaoğlu M, Aksan G, Dursun P, Dogan NU, Yuce K, Ayhan A (2008) A third evaluation of tertiary cytoreduction. J Surg Oncol 98(7): 530–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter P, du Bois A, Hahmann M, Hasenburg A, Burges A, Loibl S, Gropp M, Huober J, Fink D, Schröder W, Muenstedt K, Schmalfeldt B, Emons G, Pfisterer J, Wollschlaeger K, Meerpohl HG, Breitbach GP, Tanner B, Sehouli J (2006) Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the AGO DESKTOP Ovar trial. Ann Surg Oncol 13(12): 1702–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter P, Hahmann M, Lueck HJ, Poelcher M, Wimberger P, Ortmann O, Canzler U, Richter B, Wagner U, Hasenburg A, Burges A, Loibl S, Meier W, Huober J, Fink D, Schroeder W, Muenstedt K, Schmalfeldt B, Emons G, du Bois A (2009) Surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: role of peritoneal carcinomatosis: exploratory analysis of the DESKTOP I Trial about risk factors, surgical implications, and prognostic value of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol 16(5): 1324–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hızlı D, Boran N, Yılmaz S, Turan T, Altınbaş SK, Celik B, Köse MF (2012) Best predictors of survival outcome after tertiary cytoreduction in patients with recurrent platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 163(1): 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics: Changing in definitions of clinical staging for carcinoma of the cervix and ovary (1987) Am J Obstet Gynecol 156: 263–264 [PubMed]

- Karam AK, Santillan A, Bristow RE, Giuntoli R, Gardner GJ, Cass I, Karlan BY, Li AJ (2007) Tertiary cytoreductive surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: selection criteria and survival outcome. Gynecol Oncol 104(2): 377–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Shih IeM (2008) Pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: lessons from morphology and molecular biology and their clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol 27(2): 151–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Shih IeM (2010) The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol 34(3): 433–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Visvanathan K, Roden R, Wu TC, Shih IeM (2008) Early detection and treatment of ovarian cancer: shifting from early stage to minimal volume of disease based on a new model of carcinogenesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198(4): 351–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao MM, Kardos S, Barakat RR, Chi DS (2004) Tertiary cytoreduction in patients with recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 95: 181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfisterer J, Harter P, Canzler U, Richter B, Jackisch C, Hahmann M, Hasenburg A, Burges A, Loibl S, Gropp M, Huober J, Fink D, Bois A AGO Ovarian Committee; AGO Ovarian Cancer Study Group (AGO-OVAR) (2005) The role of surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 15(Suppl 3): 195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorge JO, Wingo SN, Bhore R, Heffernan TP, Lea JS (2010) Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 108(2): 123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehouli J, Könsgen D, Mustea A, Oskay-Ozcelik G, Katsares I, Weidemann H, Lichtenegger W (2003) ‘IMO’–intraoperative mapping of ovarian cancer. Zentralbl Gynakol 125(3–4): 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehouli J, Senyuva F, Fotopoulou C, Neumann U, Denkert C, Werner L, Gülten OO (2009) Intra-abdominal tumor dissemination pattern and surgical outcome in 214 patients with primary ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol 99(7): 424–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih IeM, Kurman RJ (2005) Molecular pathogenesis of ovarian borderline tumors: new insights and old challenges. Clin Cancer Res 11(20): 7273–7279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih IeM, Kurman RJ (2004) Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol 164(5): 1511–1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih KK, Chi DS, Barakat RR, Leitao MM (2010a) Tertiary cytoreduction in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer: an updated series. Gynecol Oncol 117: 330–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih KK, Chi DS, Barakat RR, Leitao MM (2010b) Beyond tertiary cytoreduction in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 116(3): 364–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer G, Kurman RJ, Chang H-W, Cho SKR, Shih I-M (2002) Diverse tumorigenic pathways in ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Pathol 160: 1223–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vang R, IeM Shih, Kurman RJ (2009) Ovarian low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma: pathogenesis, clinicopathologic and molecular biologic features, and diagnostic problems. Adv Anat Pathol 16(5): 267–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberger P, Wehling M, Lehmann M, Kimmig R, Schmalfeldt B, Burges A, Harter P, Pfisterer J, du Bois A (2010) Influence of residual tumor on outcome in ovarian cancer patients with FIGO stage IV disease. An exploratory analysis of the AGO-OVAR (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Cancer Study Group). Ann Surg Oncol 17: 1642–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivanovic O, Eisenhauer EL, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Sabbatini P, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR, Chi DS (2008) The impact of bulky upper abdominal disease cephalad to the greater omentum on surgical outcome for stage IIIC epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 108(2): 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]