Abstract

Background:

Sleep duration is dependent on circadian rhythm that controls a variety of key cellular functions. Circadian disruption has been implicated in colorectal tumorigenesis in experimental studies. We prospectively examined the association between sleep duration and risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).

Methods:

In the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, 75 828 postmenopausal women reported habitual sleep duration at baseline 1993–1998. We used Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of CRC and its associated 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results:

We ascertained 851 incident cases of CRC through 2010, with an average 11.3 years of follow-up. Compared with 7 h of sleep, the HRs were 1.36 (95% CI 1.06–1.74) and 1.47 (95% CI 1.10–1.96) for short (⩽5 h) and long (⩾9 h) sleep duration, respectively, after adjusting for age, ethnicity, fatigue, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), physical activity, and waist to hip ratio. The association was modified by the use of HRT (P-interaction=0.03).

Conclusion:

Both extreme short and long sleep durations were associated with a moderate increase in the risk of CRC in postmenopausal women. Sleep duration may be a novel, independent, and potentially modifiable risk factor for CRC.

Keywords: sleep, colorectal neoplasms, risk factors, women, prospective studies

Both short and long sleep durations have been associated with increased risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, as well as all-cause mortality (Gallicchio and Kalesan, 2009; Parish, 2009). However, the association between habitual sleep duration and the risk of commonly occurring cancers is largely unknown.

Earlier studies hypothesised that electric light at night disrupts the circadian rhythm and impairs the secretion of the pineal hormone melatonin. Nocturnal suppression of melatonin may lead to an elevation of circulating oestrogen levels (Stevens and Davis, 1996). Therefore, many studies have examined night shift work or rotating shift work in association with the risk of hormone-related cancers (Conlon et al, 2007; Kolstad, 2008; Poole et al, 2011). The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) evaluated experimental and epidemiologic evidence of the association between shift work and various cancers (IARC, 2010). The panel concluded that there was sufficient experimental evidence from animal studies that have demonstrated that light at night can substantially promote the development of different types of tumours. There was consistent evidence for an association between night shift work and breast cancer in adequately designed epidemiologic studies; however, the evidence for other types of cancer was very limited owing to inconsistent study findings. Therefore, IARC classified ‘shift work that involves circadian disruption’ as a ‘probably carcinogenic to human (group 2A)’(IARC, 2010; Straif et al, 2007).

Recent studies, including a few genome-wide association studies, have implicated circadian rhythm in various aspects of carcinogenesis, including DNA damage response, DNA repair, glucose metabolism and immune suppression (Bass and Takahashi, 2010; Dupuis et al, 2010; Sancar et al, 2010; Froy, 2011). Several lines of evidence suggest a potential role of circadian rhythm in colorectal cancer (CRC) development (Wood et al, 2008; Alhopuro et al, 2010; Basterfield and Mathers, 2010). For example, inactivation of the Period 2 gene accelerated intestinal and colonic tumorigenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice (Wood et al, 2008). In the Min mice, strong significant positive correlations between sleep duration and both tumour multiplicity and burden were observed (Basterfield and Mathers, 2010). In humans, somatic mutations of the CLOCK gene have been frequently found in microsatellite-instable CRC (Alhopuro et al, 2010).

In spite of enhanced understanding on the physiology of circadian rhythm in metabolism homeostasis and colorectal tumorigenesis, habitual sleep duration, an important and potentially modifiable lifestyle factor, in association with CRC has not been examined in population-based studies. We therefore tested the hypothesis that sleep duration is associated with the risk of CRC in a large cohort of postmenopausal women. As hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been shown to improve sleep quality in postmenopausal women (Polo-Kantola et al, 1998; Welton et al, 2008), we performed an a priori analysis to test the interaction between HRT and sleep duration. In addition, we examined the association between other sleep habits and risk of CRC.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Women’s Health Initiative–Observational Study (WHI-OS) is a multiethnic cohort of 93 676 US women who were recruited from 40 clinical centres in 24 states and the District of Columbia, between September 1993 and December 1998. Detailed information on the study population, recruitment methods, and measurement protocols was previously published (WHI, 1998). All women provided written informed consent. The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of each participating clinical centre. The IRB at Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center approved this analysis.

Among 93 676 women included in the initial WHI-OS, we excluded 12 075 women who reported a history of cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer at baseline, 752 with unknown cancer history, 480 with missing data on sleep duration and quality, 3090 with daily energy intake of <600 Kcal or>5000 Kcal, and 71 who did not have the data on energy intake. We also excluded 1380 women who were censored (death or diagnosis of CRC) during the first 2 years of follow-up to account for potential reverse causality, that is, change of sleep duration or habits as a result of subclinical CRC. The final analytic cohort consisted of 75 828 women.

Case ascertainment

The outcome of interest was incident CRC that was defined according to International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICDO) 2rd edition site codes C18.0–C18.9, C19.9, and C20.9. Cases with CRC were ascertained through September 2010 using annual self-administered questionnaires. All cases included in the present analysis were centrally adjudicated by trained physicians at each clinical centre. Vital status was ascertained through follow-up questionnaires and National Death Index searches.

Data collection

At the baseline screening visit, women completed a questionnaire to provide detailed information on ‘Thoughts and Feelings’, including sleep habits and psychosocial factors. The measures of sleep habits in the WHI Study were developed by sleep researcher consultants to the WHI Behavioural Advisory Committee (Levine et al, 2003). Ten questions were used to assess sleep habits in the past 4 weeks: (1) ‘Did you take any kind of medication or alcohol at bedtime to help you sleep?’ (2) ‘Did you fall asleep during quiet activity like reading, watching TV, or riding in car?’ (3) ‘Did you nap during the day?’ (4) ‘Did you have trouble falling asleep?’ (5) ‘Did you wake up several times at night?; (6) ‘Did you wake up earlier than you planned to?’ (7) ‘Did you have trouble getting back to sleep after you woke up too early?’ (8) ‘Did you snore?’ (9) ‘Overall, how was your typical night’s sleep during the past 4 weeks?’ and (10) ‘About how many hours of sleep did you get on a typical night during the past 4 weeks?’. Question #9 was used to define sleep quality that ranges from very sound or restful, sound or restful, average quality, restless, and to very restless. Question #10 was used to define sleep duration with categories of ⩽5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and ⩾10 h. For all other questions, a five-point scale (0,<1, 1–2, 3–4, and ⩾5 times per week) was used to evaluate the response, with an additional choice of ‘Don’t know’ for self-reported snoring. Sleep disturbance was defined as having frequent experience (⩾3 times per week) of each habit.

We used validated constructed scores to evaluate several psychosocial factors, including depression, fatigue, pain, social strain, and care giving. The constructed score incorporates the responses to several related questions on ‘Thoughts and Feelings’ questionnaire. For example, depressive symptoms were assessed with a scale that used 6-item from 20-item Center For Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Burnam et al, 1988).

At baseline, women completed structured questionnaires to provide information on demographic features, lifestyle factors, medical history, medications use, hormone use, reproductive history, and family history of diseases. Physical measures of weight, height, and waist and hip circumference were also taken. Physical activity was assessed by computing average weekly metabolic equivalent of task (MET) of moderate and vigorous leisure-time physical activity. Participants completed a validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire that inquired about usual intake of 122 food items in the past 3 months (Patterson et al, 1999).

Statistical analysis

Person–years of follow-up were calculated from the third year after the date of response to the baseline questionnaire to the date of first diagnosis of CRC, death, loss to follow-up, or 17 September 2010, whichever occurred first. We examined the characteristics of the study subjects, including sleep habits, across levels of sleep duration using the χ2 test for the categorical variables and ANOVA for the continuous variables. The absolute incidence rates for CRC according to sleep duration were standardized within 5-year age categories to the age distribution of person–years for our entire study cohort. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of CRC in relation to sleep duration. We used the most prevalent category, 7 h of sleep, as the reference group in the main analysis. However, because the risk estimates for 7 and 8 h of sleep were the same, we used combined 7 and 8 h of sleep as the normative reference group in subsequent analyses in order to attain more stable risk estimates. Nine and ⩾10 h of sleep were combined to form the extreme long sleep duration category because only 401 women reported sleeping for ⩾10 h per night. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by including an interaction term for sleep duration or key confounding variables by age and no variable was shown to violate this assumption. The potential confounding factors evaluated included age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, body mass index (BMI), or waist to hip ratio (WHR), physical activity, psychosocial factors, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, medical history, use of colonoscopy, HRT, reproductive factors, first-degree family history of CRC, frequency of sleep habits, and daily energy and food intake. We selected a parsimonious model by including confounding factors that were associated with risk of CRC and that changed the risk estimates for sleep duration by 10% or more. Waist to hip ratio and physical activity did not change the risk estimates by >10% however these variables were included in all the models because they are known risk factors for CRC in women. The missing information for the confounding factors was coded as a missing category for data analysis. In addition, we plotted the adjusted HRs against each category of sleep duration. In examining the frequency of sleep habits in association with incident CRC, we used the ‘No event or less than 3 times per week’ as the reference group and sleep duration was included as an additional factor in the models.

Stratified analyses were performed according to tumour site (colon vs rectum, and proximal vs distal), as well as diabetes (yes vs no), WHR (< vs ⩾median value), use of HRT (never vs ever), and physical activity (< vs⩾median value of weekly MET). The ICDO2 site codes were used to define the tumour location, including proximal tumours (codes 18.0, 18.2, 18.3, 18.4, and 18.5) and distal tumours (codes 18.6, 18.7, 19.9, and 20.9). The cases (n=102) with nonspecified code were not included in this analysis. We also evaluated the joint effect of sleep duration (⩽5, 6–8, and ⩾9 h) and sleep quality (very restless and restless, average, sound and very sound) in association with incident CRC. Significance of interaction was tested using the Wald test. The missing category for each stratified variable was excluded from the stratified analyses. A lag analysis was performed by excluding women censored in the first 5 years of follow-up in order to account further for reverse causality.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and P-values <0.05 indicate statistical significance. SAS 9.0 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used in statistical analysis.

Results

During an average 11.3 (s.d. 3.1, range 2–15) years of follow-up, 851 incident first primary CRC cases were identified, including 700 with colon cancer, 111 with rectal cancer, and 40 with rectosigmoid cancer. There were 461 proximal and 288 distal CRCs. The average age of study participant was 63.5 years at baseline.

Table 1 shows that 38% of women reported sleeping for 7 h per night in the WHI study population. Short sleep duration (⩽5 h) was reported more commonly among African Americans and among those with lower educational and family income levels, unfavourable psychosocial profiles, or characteristics of sleep disturbance. Women who reported long sleep duration (⩾9 h) were older and less likely to have trouble falling asleep and had less energy expenditure from moderate and vigorous recreational physical activity. Energy intake, average daily intake of total fat, saturated fat, red meat, fruit and vegetable, folate, total carbohydrate, fibre, vitamin D, and calcium were not significantly associated with sleep duration (results not shown).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects according to habitual sleep duration in the WHI-OS (1994–2010).

|

Sleep duration (hours per night)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics (mean (s.d.) or %) | ⩽5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ⩾9 | P -value a |

| No. of participants | 5927 | 20 267 | 28 914 | 17 293 | 3427 | |

| Prevalence (%) | 7.8 | 26.7 | 38.1 | 22.8 | 4.5 | |

| Age at baseline, years | 63.5 (7.6) | 63.3 (7.4) | 63.1 (7.3) | 63.6 (7.1) | 64.0 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 68.0 | 79.8 | 87.4 | 89.6 | 87.0 | |

| African American | 17.5 | 9.9 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 6.8 | |

| Hispanic | 6.0 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 4.0 | |

| Asian/Pacific island | 5.6 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |

| Other | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.0 | |

| Missing | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Education (no college, %) | 39.6 | 31.6 | 27.7 | 28.6 | 30.8 | <0.001 |

| Employment (currently work, %) | 34.6 | 35.1 | 34.6 | 34.8 | 33.8 | 0.54 |

| Total family income ($) (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| <20,000 | 22.8 | 15.1 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 16.5 | |

| 20 000–34 999 | 23.7 | 22.6 | 20.5 | 20.8 | 21.7 | |

| 35 000–49 999 | 16.6 | 18.9 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 18.6 | |

| 50 000–74 999 | 15.3 | 18.1 | 20.3 | 19.9 | 17.9 | |

| ⩾75 000 | 13.3 | 18.2 | 21.7 | 20.6 | 17.3 | |

| Missing/do not know | 8.3 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 11.5 | |

|

Lifestyle factors

| ||||||

| Never smokers (%) | 50.7 | 49.9 | 50.0 | 50.4 | 49.9 | 0.77 |

| Years of smoking in smokers | 0.56 | |||||

| <20 | 21.2 | 21.8 | 21.5 | 21.6 | 22.0 | |

| ⩾20 | 25.2 | 25.7 | 26.0 | 25.2 | 25.6 | |

| Never smoked and missing | 53.6 | 52.5 | 52.5 | 53.2 | 52.5 | |

| No. of cigarettes smoked per day | 0.53 | |||||

| <15 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 10.6 | |

| 15–24 | 14.7 | 15.0 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 15.5 | |

| ⩾25 | 20.8 | 21.0 | 21.6 | 21.1 | 20.8 | |

| Never smoked and missing | 53.9 | 52.8 | 52.9 | 53.7 | 53.1 | |

| Alcohol (serving per week) | 2.3 (4.7) | 2.4 (4.8) | 2.4 (4.8) | 2.4 (4.7) | 2.4 (5.2) | 0.89 |

| Physical activityb | 12.3 (13.7) | 12.5 (13.5) | 12.5 (13.9) | 12.3 (13.6) | 11.9 (13.2) | 0.08 |

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.74 |

| Body mass index, kg m−2 | 27.9 (5.9) | 28.0 (5.9) | 27.9 (5.9) | 27.9 (5.9) | 28.0 (5.8) | 0.71 |

| Total energy intake, kcal | 1613 (707) | 1632 (730) | 1624 (704) | 1621 (744) | 1609 (698) | 0.14 |

|

Medical history and medication (yes, %)

| ||||||

| Screening colonoscopy | 48.8 | 49.1 | 48.9 | 48.7 | 48.9 | 0.98 |

| Colorectal polyps removed | 9.33 | 8.76 | 8.83 | 8.47 | 8.61 | 0.79 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1.21 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 0.34 |

| Treated type 2 diabetes | 4.13 | 4.27 | 4.59 | 4.57 | 4.29 | 0.36 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 16.1 | 17.0 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 0.74 |

| Hypertension | 34.2 | 33.7 | 33.8 | 33.4 | 32.6 | 0.20 |

| First-degree family history of CRC | 14.9 | 15.2 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 14.9 | 0.90 |

| Use of NSAIDs | 19.6 | 19.2 | 19.3 | 19.0 | 18.4 | 0.56 |

|

Frequency of sleep habits (⩾3 times per week, %)

| ||||||

| Use of sleeping pill | 9.13 | 9.08 | 9.18 | 8.64 | 9.31 | 0.66 |

| Fall asleep during quiet activity | 37.9 | 30.4 | 23.7 | 20.3 | 24.1 | <0.001 |

| Nap during the day | 16.6 | 12.9 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 19.1 | <0.001 |

| Trouble falling sleeping | 34.4 | 12.7 | 5.19 | 3.64 | 5.78 | <0.001 |

| Wake up several times | 65.0 | 43.6 | 34.3 | 33.1 | 36.8 | <0.001 |

| Wake up earlier than planned | 49.4 | 25.7 | 13.0 | 8.01 | 8.11 | <0.001 |

| Trouble getting back to sleep | 47.8 | 21.8 | 9.20 | 5.27 | 5.25 | <0.001 |

| Very restless sleep | 14.2 | 2.13 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 1.08 | <0.001 |

| Snoring | 16.2 | 15.0 | 14.4 | 15.8 | 18.5 | <0.001 |

|

Psychosocial factors (%)

| ||||||

| Depression (CES-D>0.06)c | 24.0 | 13.1 | 7.95 | 7.11 | 12.6 | <0.001 |

| More fatigue (score⩽65)d | 65.9 | 52.5 | 46.0 | 44.9 | 56.7 | <0.001 |

| More pain (score<75) (%)e | 47.3 | 34.6 | 29.2 | 28.6 | 35.5 | <0.001 |

| More social strain (score >10)f | 13.9 | 9.04 | 6.36 | 5.83 | 6.70 | <0.001 |

| Care giving ⩾3 times per week | 12.1 | 9.67 | 8.44 | 8.00 | 9.00 | <0.001 |

|

Reproductive factors (%)

| ||||||

| Pregnant ever | 90.7 | 90.6 | 90.4 | 90.5 | 90.8 | 0.47 |

| Oral contraceptive ever use | 41.8 | 42.0 | 41.3 | 41.2 | 41.5 | 0.78 |

| Age at menopause, year | 47.9 (6.5) | 48.1 (6.4) | 48.1 (6.4) | 48.0 (6.4) | 48.2 (6.5) | 0.23 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 0.05 | |||||

| Never | 33.2 | 32.4 | 32.4 | 32.9 | 31.1 | |

| Former user | 22.8 | 21.9 | 22.4 | 22.9 | 24.0 | |

| Current user | 41.1 | 42.8 | 42.3 | 41.3 | 42.5 | |

Abbreviations: CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CRC=colorectal cancer; NSAIDs=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; WHI-OS=Women’s Health Initiative–Observational Study.

P-value for χ2 test or analysis of variance.

Metabolic equivalent of task (hour per week): total energy expenditure from moderate and vigorous recreational physical activity.

Depression (CES-D ranges from 0 to 1). A higher score indicates a greater likelihood of depression. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale >0.06 was used to indicate depression.

Fatigue score (ranges from 0 to 100). A higher score indicates less fatigue.

Pain score (ranges from 0 to 100). A higher score indicates a more favourable condition.

Social strain score (ranges from 4 to 20). A higher score indicates more strain.

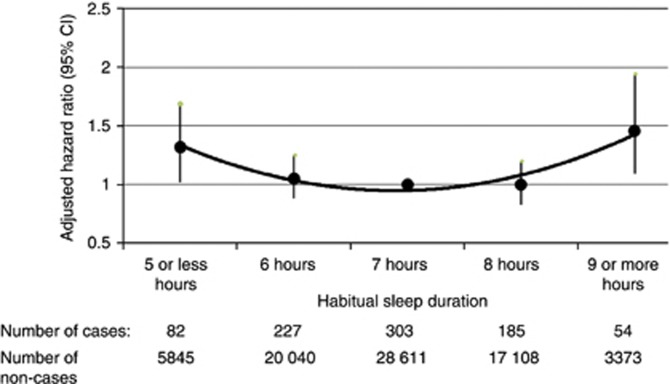

Table 2 shows the age-adjusted incidence rates as well as the risk estimates of colon and rectal cancers, separately as well as collectively according to sleep duration. Both short and long sleep duration were associated with a significantly moderate increase in risk of CRC. The final model included age (continuous), ethnicity, constructed variable for fatigue (continuous), use of HRT (never, past, current, and missing), WHR, and physical activity (dichotomous by median value of WHR or MET, and missing). The adjustment of other sleep habits did not change the risk estimate for sleep duration. Figure 1 shows a U-shaped pattern of risk of CRC according to individual category of sleep duration. When the combined 7 and 8 h of sleep was used as the reference group, the HRs were 1.32 (95% CI 1.04–1.68) for short and 1.46 (95% CI 1.10–1.93) for long sleep duration. We also observed a slightly insignificant increased risk of colon and rectum cancer, as well as proximal and distal colon cancers, in association with both short and long sleep duration.

Table 2. Associations between habitual sleep duration and risk of colorectal cancer in the WHI-OS (1994–2010).

| Sleep duration (hours per night) | No. of cases | Age-adjusted incidence rate/100,000 person–years) | HR a | 95% CI | HR b | 95% CI | HR c | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Colorectal cancer

d

| ||||||||

| Total cases | 851 | |||||||

| ⩽5 | 82 | 131.4 | 1.46 | 1.14, 1.86 | 1.42 | 1.11, 1.81 | 1.36 | 1.06, 1.74 |

| 6 | 227 | 100.8 | 1.11 | 0.93, 1.32 | 1.09 | 0.92, 1.30 | 1.08 | 0.91, 1.28 |

| 7 | 303 | 91.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 8 | 185 | 93.8 | 1.03 | 0.86, 1.23 | 1.00 | 0.84, 1.20 | 1.01 | 0.84, 1.21 |

| ⩾9 | 54 | 142.4 | 1.57 | 1.17, 2.09 | 1.49 | 1.12, 2.00 | 1.47 | 1.10, 1.96 |

|

Colon cancer

| ||||||||

| Total cases | 700 | |||||||

| ⩽5 | 62 | 98.4 | 1.32 | 1.01, 1.73 | 1.29 | 0.98, 1.68 | 1.20 | 0.91, 1.58 |

| 6 | 192 | 85.4 | 1.12 | 0.94,1.33 | 1.11 | 0.94, 1.32 | 1.08 | 0.90, 1.28 |

| 7–8 | 404 | 76.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| ⩾9 | 42 | 106.6 | 1.46 | 1.06, 2.00 | 1.40 | 1.02, 1.92 | 1.36 | 0.99, 1.87 |

|

Rectal cancer

| ||||||||

| Total cases | 111 | |||||||

| ⩽5 | 12 | 19.0 | 1.58 | 0.85, 2.92 | 1.56 | 0.84, 2.89 | 1.53 | 0.81, 2.88 |

| 6 | 26 | 11.6 | 0.94 | 0.60, 1.49 | 0.94 | 0.60, 1.48 | 0.94 | 0.59, 1.48 |

| 7–8 | 65 | 12.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| ⩾9 | 8 | 20.5 | 1.72 | 0.82, 3.58 | 1.68 | 0.81, 3.50 | 1.68 | 0.80, 3.50 |

|

Proximal cancers

| ||||||||

| Total cases | 461 | |||||||

| ⩽5 | 41 | 64.7 | 1.32 | 0.95,1.83 | 1.28 | 0.92, 1.77 | 1.20 | 0.86, 1.68 |

| 6 | 122 | 53.9 | 1.07 | 0.86,1.33 | 1.06 | 0.86, 1.32 | 1.04 | 0.84, 1.29 |

| 7–8 | 269 | 50.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| ⩾9 | 29 | 73.3 | 1.51 | 1.03, 2.22 | 1.44 | 0.98, 2.12 | 1.39 | 0.95, 2.04 |

|

Distal cancers

| ||||||||

| Total cases | 288 | |||||||

| ⩽5 | 29 | 46.6 | 1.42 | 0.96, 2.10 | 1.40 | 0.95, 2.08 | 1.32 | 0.89, 1.98 |

| 6 | 69 | 30.7 | 0.93 | 0.71, 1.23 | 0.93 | 0.70, 1.23 | 0.92 | 0.69 1.21 |

| 7–8 | 174 | 32.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| ⩾9 | 16 | 41.0 | 1.29 | 0.77, 2.15 | 1.26 | 0.75, 2.10 | 1.21 | 0.72, 2.02 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; WHI-OS=Women’s Health Initiative–Observational Study.

Crude HR.

HR was adjusted for age.

HR was adjusted for age, ethnicity, fatigue, hormone replacement therapy, waist to hip ratio, and physical activity.

Includes cancers of colon, rectum, and rectosigmoid.

Figure 1.

Plot of hazard ratios and 95% CIs of colorectal cancer according to habitual sleep duration per night. Seven-hour is the reference group. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, ethnicity, fatigue, HRT, WHR, and physical activity.

Table 3 shows the prevalence of sleep disturbance ranged from 10% to 40% for frequent ‘use of sleeping pills’ to frequent ‘wake up several times at night’, respectively. Frequent ‘trouble falling asleep’, ‘nap in the day’, ‘wake up several times at night’, and ‘trouble getting back to sleep’ were each associated with a moderate significant increase of risk of CRC in the univariate analysis. However, the association with frequent ‘nap in the day’ was attenuated by >10% after age adjustment. The observed associations for other factors were attenuated by 8–10% when age and other confounding factors were included in the model. Adjustment for sleep duration further attenuated slightly the association between frequent ‘trouble falling sleep or getting back to sleep’ and risk of CRC. ‘Very restless sleep’ compared with ‘average sleep quality’ was associated with increased risk of CRC, albeit the analysis was based on a restricted sample size.

Table 3. Associations between weekly frequency of sleep disturbance and risk of colorectal cancer in the WHI-OS (1994–2010).

| 0 or <3 times | ⩾3 times | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly sleep habits | Cases a | HR b | Prevalence c | Cases a | HRb,d | 95% CI | HR b , e | 95% CI | HR b , f | 95% CI | HR b , g | 95% CI |

| Use of sleeping pil | 770 | 1.00 | 10.0% | 76 | 0.98 | 0.77, 1.24 | 0.98 | 0.78-1.24 | 0.99 | 0.78, 1.26 | 0.99 | 0.78, 1.26 |

| Fall asleep during quiet activity | 618 | 1.00 | 24.3% | 223 | 1.10 | 0.95, 1.28 | 1.10 | 0.95, 1.28 | 1.07 | 0.92, 1.25 | 1.06 | 0.92, 1.24 |

| Nap in the day | 707 | 1.00 | 13.9% | 140 | 1.36 | 1.13, 1.62 | 1.14 | 0.95, 1.37 | 1.10 | 0.92, 1.33 | 1.10 | 0.91, 1.32 |

| Trouble falling asleep | 756 | 1.00 | 10.8% | 94 | 1.30 | 1.05, 1.61 | 1.25 | 1.01, 1.55 | 1.20 | 0.96, 1.50 | 1.15 | 0.91, 1.44 |

| Wake up several times | 481 | 1.00 | 40.2% | 361 | 1.18 | 1.03, 1.36 | 1.10 | 0.96, 1.27 | 1.06 | 0.92, 1.22 | 1.04 | 0.90, 1.20 |

| Wake up early than planned | 678 | 1.00 | 18.0% | 170 | 1.17 | 0.99, 1.39 | 1.15 | 0.98, 1.37 | 1.12 | 0.94, 1.33 | 1.09 | 0.91, 1.30 |

| Trouble getting back to sleep | 698 | 1.00 | 15.0% | 151 | 1.31 | 1.10, 1.56 | 1.26 | 1.06, 1.51 | 1.22 | 1.02, 1.46 | 1.19 | 0.98, 1.44 |

| Snoring | 275 | 1.00 | 16.5% | 143 | 1.20 | 0.98, 1.46 | 1.20 | 0.98, 1.47 | 1.16 | 0.95, 1.43 | 1.16 | 0.95, 1.42 |

| Poor sleep quality (very restless) | 352 | 1.00 | 2.4% | 23 | 1.39 | 0.91, 2.11 | 1.52 | 1.00, 2.32 | 1.42 | 0.93, 2.17 | 1.23 | 0.78, 1.92 |

Abbreviations: cases=number of incident cases; CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; WHI-OS=Women’s Health Initiative–Observational Study.

Two columns showed the number of cases who had less frequent sleep habit/disturbance (0 or <3 times per week) or frequent sleep habit/disturbance (⩾3 times per week), respectively. For variable ‘snoring’, many women did not report whether they snored. For variable ‘poor sleep quality’, there were 352 reported average sleep quality and 23 reported very restless sleep. The numbers in the two columns do not add up to 851 because of the missing information.

Those who reported no or less frequent experience of certain sleep habit served as the reference group, and the more frequent experience of certain habits was the comparison group.

The prevalence of the frequent experience of each sleep habit/disturbance (⩾3 times per night) in the study population.

Crude HR.

HR was adjusted for age.

HR was adjusted for age, ethnicity, fatigue, hormone replacement therapy, waist to hip ratio, and physical activity.

HR was adjusted for sleep duration in addition.

The association between sleep duration and the risk of CRC was strengthened in the 5-year lag analysis based on 572 cases. Compared with 7 h of sleep, the HRs were 1.46 (95% CI 1.08–1.97) for short and 1.59 (95% CI 1.13–2.25) for long sleep duration, after adjusting for the same confounding factors as in the main analysis.

Table 4 shows the interaction of sleep duration by use of HRT (P-value for interaction 0.03). Short sleep duration was associated with an increased risk among women who never received HRT, but not among their counterparts who received HRT. On the other hand, long sleep duration was associated with an increased risk of CRC only among women who ever received HRT, but not among women who never received HRT. There was no interaction by WHR, physical activity, diabetes, or sleep quality (P-values for interaction=0.34, 0.69, 0.94, and 0.21, respectively).

Table 4. Association between sleep duration and risk of colorectal cancer by use of HRT in the WHI-OS (1994–2010).

| HRT | Never ( n =24 681) | Ever ( n =48 986) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration (hours per night) | Cases a | HR b | 95% CI | Cases a | HR b | 95% CI | P -value c |

| ⩽5 | 41 | 1.75 | 1.23, 2.50 | 40 | 1.07 | 0.78, 1.50 | |

| 6 | 88 | 1.12 | 0.86, 1.45 | 134 | 1.01 | 0.82, 1.24 | |

| 7–8 | 174 | 1.00 | 305 | 1.00 | |||

| ⩾9 | 13 | 1.00 | 0.57, 1.76 | 40 | 1.70 | 1.22, 2.37 | 0.03 |

Abbreviation: cases=number of incident case; CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; HRT=hormone replacement therapy; WHI-OS=Women’s Health Initiative–Observational Study.

The analysis was based on 73 667 women who reported the use of HRT.

HR was adjusted for age, ethnicity, fatigue, waist to hip ratio, and physical activity.

P-value for interaction.

Discussion

In this well-established large cohort of postmenopausal women in the United States, we found that self-reported extreme habitual sleep duration, either short (⩽5 h) or long (⩾9 h), was significantly associated with a moderate increase in risk of CRC independent of a number of confounding factors, compared with the normally recommended hours of sleep, 7–8 h per night. A U-shaped association was observed. The association between sleep duration and risk of CRC was modified by HRT. Frequent experience (⩾3 times per week) of trouble falling asleep or getting back to sleep was associated with slightly increased risk of CRC. The association may be partially mediated by sleep duration.

Two previous studies on night shift work and the risk of CRC generated inconsistent findings. A prospective cohort study has shown that longer years of rotating night shift work was associated with moderately increased risk of CRC among female nurses (Schernhammer et al, 2003). However, the other study did not find an association between night shift work and colon or rectal cancer among women naval radio–telegraph operators (Tynes et al, 1996).

Only seven studies have investigated the association between sleep duration and cancer risk. The study findings from four prospective studies and one population-based study on sleep duration and risk of breast cancer were mixed (Verkasalo et al, 2005; McElroy et al, 2006; Pinheiro et al, 2006; Wu et al, 2008; Kakizaki et al, 2008b). One Japanese prospective study has associated long sleep duration with a decreased risk of prostate cancer (Kakizaki et al, 2008a). No association was found for sleep duration and endometrial cancer in the WHI-OS (Sturgeon et al, 2012). In a large prospective study in Europe,<6 h of sleep was associated with moderately increased overall cancer incidence compared with 7–8 h of sleep (von et al, 2012). Owing to the paucity of the research, no conclusion can be drawn on sleep duration and cancer risk.

Until the present study, there has been no prospective study on sleep duration and risk of CRC. We observed a U-shaped association between sleep duration and incidence of CRC. A similar pattern has been reported for sleep duration and coronary heart disease (Ayas et al, 2003), type 2 diabetes (Yaggi et al, 2006), and all-cause mortality (Parish, 2009). The association between short sleep duration and an increased risk of CRC was in line with the finding from a colonoscopy-based case–control study of 338 cases and 902 controls, which showed a 50% increase in risk of colorectal adenoma for <6 h compared with ⩾7 h of sleep. However, this study did not report the association between long sleep duration and risk of colorectal adenoma (Thompson et al, 2011). Our observation on the association between long sleep duration and increased risk of CRC was consistent with a retrospective hospital-based case–control study in Hong Kong among 822 cases with CRC and 926 controls, which found that cases slept for significantly longer hours than controls did (Ho et al, 2006).

The mechanisms underlying the observed positive associations between extreme short and long sleep durations and risk of CRC are unknown and likely to be different. The harm of short sleep or sleep restriction has been well-recognised, including impaired glucose and appetite control (Grandner et al, 2010) and compromised immune function. Sleep enhances adaptive immune responses, whereas sleep disturbances can lead to immune suppression and a shift to a predominance of cancer-stimulatory cytokines (Dimitrov et al, 2007). There is no consensus on the probable mechanisms for the harm of long sleep. Our study finding on the positive association between long sleep duration and risk of CRC may not be explained by the melatonin hypothesis. A previous study has shown that a higher endogenous estradiol level is an independent risk factor for CRC in the WHI Study (Gunter et al, 2008). If long sleep duration was thought to decrease oestrogen levels by augmenting the production of melatonin, we would expect to observe an inverse association between long sleep duration and risk of CRC. Nevertheless, the association between the number of hours of sleep and circulating levels of melatonin has not been well-established (Viswanathan and Schernhammer, 2009), with only one cross-sectional study showing that the postmenopausal Singapore women who slept 9 or more hours a night had a 42% higher mean level of urinary melatonin than those who slept 6 or fewer hours (Wu et al, 2008). Long sleep duration is also considered being a marker of frailty and ill health (Knutson and Turek, 2006). Interestingly, we only observed the association between long sleep duration and increased risk of CRC among women who received HRT. It indicates that hormone-related mechanism may mediate such an association or vice versa. In a cross-sectional study of 614 individuals, each additional hour of sleep was significantly associated with an increase in levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6; and each hour reduction in sleep was associated with an increase in levels of tumour necrosis factor-α (Patel et al, 2009). Therefore, sleep duration may contribute to systemic inflammation and subsequently CRC.

We noticed a slight increase in risk of CRC associated with frequent experience of trouble getting back to sleep or falling asleep, snoring, and very restless sleep. Two studies have investigated sleep disturbance in association with cancer incidence or mortality. One prospective study observed a modestly increased overall cancer risk for those prescribed any hypnotic compared with non-users (Kripke et al, 2012) and the other suggested that baseline sleep-disordered breathing was associated with increased overall cancer mortality in a community-based study (Nieto et al, 2012). These two previous studies did not include sleep duration in the statistical models. It is conceivable that sleep duration partially mediated the association between trouble falling asleep or getting back to sleep, or very restless sleep and risk of CRC because sleep duration was tightly associated with these factors in our study. In light of a moderate prevalence of these sleep habits in the general population, even a slight increase in CRC risk would have a public health impact. Further research using refined ascertainment of sleep habits may identify new risk factors for CRC.

We found a statistically significant interaction between sleep duration and use of HRT. The finding suggested that HRT may not only improve sleep in postmenopausal women but also counteract potential carcinogenic effect associated with short sleep duration. The differential associations by long sleep duration were also interesting, although the underlying mechanism remains unknown. Nevertheless, our observations suggested that there is a common biological mechanism shared by HRT and regulation of sleep duration (e.g., circadian rhythm), as well as the distinct carcinogenic effect associated with short vs long sleep duration in the context of HRT. The investigation on sleep duration by different types of HRT (such as oestrogen alone or oestrogen combined with progestin) in a large study may provide more insight into such an interactive effect. Short sleep duration has been associated with obesity in cross-sectional studies (Cappuccio et al, 2008) and obesity is a risk factor for CRC. However, obesity, as well as physical activity, was not shown to be interacting with sleep duration in modifying risk of CRC in our study. Similarly, the study on colorectal adenoma also did not find BMI to be a confounding factor (Thompson et al, 2011).

Strengths of this study include its prospective design and large number of cases. We evaluated a broad spectrum of potential confounding factors that may account for the underlying association. However, residual confounding effect by recognised factors, such as fatigue, or unmeasured factors, such as undiagnosed comorbid conditions, may not have been fully accounted for in this analysis owing to potential limitations in study questionnaires. Given the prospective design of this study, the possibility of reverse causality was unlikely to explain the findings. The major analyses lagged by 2 years and the sensitivity analysis lagged by 5 years, both strengthened our confidence in the validity of the study findings.

There are several limitations to our study. First, self-reported sleep duration at study baseline may not have captured actual habitual sleep duration, but rather perceived habitual sleep duration. Subjective report can either under- or over-report sleep duration compared with objective measures using polysomnography (Bliwise and Young, 2007). This potential non-differential measurement error may dilute the association between extreme sleep duration and CRC risk. Nevertheless, one study has shown that self-reported sleep duration correlates well with actigraphic assessment of sleep (Lockley et al, 1999). Second, we did not have information on change in sleep duration over time, occupational history, including night shift work history, or nocturnal exposure to light for our study cohort. In the WHI Study, the question on nocturnal sleep duration at baseline was not ascertained during the follow-up visit. Third, as our analyses are confined to older women, the results may not be generalisable to men or younger women owing to sleep and endocrine differences by age and sex (Manber and Armitage, 1999). Finally, although short sleep duration has been associated with increased risk of colorectal adenoma (Thompson et al, 2011), we could not accurately examine colorectal adenoma because only prior history of colorectal polyp removal was queried at baseline.

In summary, insufficient sleep is a common public health issue and there is increasing awareness of the impact of sleep problems on health (Ferrie et al, 2011). It is plausible that dysregulation of a system that governs circadian endocrine, immune, and metabolic function may be linked to cancer incidence in humans (Sephton and Spiegel, 2003). Our finding of a significantly increased risk of CRC in postmenopausal women with extreme sleep duration suggests the need for additional research to replicate this finding, and to further elucidate if it represents a causal association vs an association secondary to some other unidentified factors. If confirmed, our study findings suggest that the health benefits of adequate amount of sleep, 7–8 h per night, include reduced risk of CRC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Women’s Health Initiative Programme, which is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services (contract number N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221). Dr Jiao is supported by Dan Duncan Scholar Award, Gillson Longenbaugh Foundation, and Golfers Against Cancer Organisation. Dr El-Serag is supported by grant DK078154-03 from the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Dr White was supported by grant DK081736-01 from the NIDDK. This material is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, and the Houston VA Health Services Research and Development Centre of Excellence (HFP90-020), as well as DK58338 from the NIDDK. We thank the WHI investigators and staff for their dedication, and the study participants for making the programme possible. A listing of WHI investigators can be found at http://www.whiscience.org/publications/WHI_investigators_shortlist.pdf.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- Alhopuro P, Bjorklund M, Sammalkorpi H, Turunen M, Tuupanen S, Bistrom M, Niittymaki I, Lehtonen HJ, Kivioja T, Launonen V, Saharinen J, Nousiainen K, Hautaniemi S, Nuorva K, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Orntoft T, Arango D, Lehtonen R, Karhu A, Taipale J, Aaltonen LA (2010) Mutations in the circadian gene CLOCK in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Res 8: 952–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Malhotra A, Hu FB (2003) A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med 163: 205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Takahashi JS (2010) Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science 330: 1349–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basterfield L, Mathers JC (2010) Intestinal tumours, colonic butyrate and sleep in exercised Min mice. Br J Nutr 104: 355–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliwise DL, Young TB (2007) The parable of parabola: what the U-shaped curve can and cannot tell us about sleep. Sleep 30: 1614–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Wells KB, Leake B, Landsverk J (1988) Development of a brief screening instrument for detecting depressive disorders. Med Care 26: 775–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, Miller MA (2008) Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep 31: 619–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon M, Lightfoot N, Kreiger N (2007) Rotating shift work and risk of prostate cancer. Epidemiology 18: 182–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov S, Lange T, Nohroudi K, Born J (2007) Number and function of circulating human antigen presenting cells regulated by sleep. Sleep 30: 401–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, Saxena R, Soranzo N, Jackson AU, Wheeler E, Glazer NL, Bouatia-Naji N, Gloyn AL, Lindgren CM, Magi R, Morris AP, Randall J, Johnson T, Elliott P, Rybin D, Thorleifsson G, Steinthorsdottir V, Henneman P, Grallert H, Dehghan A, Hottenga JJ, Franklin CS, Navarro P, Song K, Goel A, Perry JR, Egan JM, Lajunen T, Grarup N, Sparso T, Doney A, Voight BF, Stringham HM, Li M, Kanoni S, Shrader P, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Kumari M, Qi L, Timpson NJ, Gieger C, Zabena C, Rocheleau G, Ingelsson E, An P, O’Connell J, Luan J, Elliott A, McCarroll SA, Payne F, Roccasecca RM, Pattou F, Sethupathy P, Ardlie K, Ariyurek Y, Balkau B, Barter P, Beilby JP, Ben-Shlomo Y, Benediktsson R, Bennett AJ, Bergmann S, Bochud M, Boerwinkle E, Bonnefond A, Bonnycastle LL, Borch-Johnsen K, Bottcher Y, Brunner E, Bumpstead SJ, Charpentier G, Chen YD, Chines P, Clarke R, Coin LJ, Cooper MN, Cornelis M, Crawford G, Crisponi L, Day IN, de Geus EJ, Delplanque J, Dina C, Erdos MR, Fedson AC, Fischer-Rosinsky A, Forouhi NG, Fox CS, Frants R, Franzosi MG, Galan P, Goodarzi MO, Graessler J, Groves CJ, Grundy S, Gwilliam R, Gyllensten U, Hadjadj S, Hallmans G, Hammond N, Han X, Hartikainen AL, Hassanali N, Hayward C, Heath SC, Hercberg S, Herder C, Hicks AA, Hillman DR, Hingorani AD, Hofman A, Hui J, Hung J, Isomaa B, Johnson PR, Jorgensen T, Jula A, Kaakinen M, Kaprio J, Kesaniemi YA, Kivimaki M, Knight B, Koskinen S, Kovacs P, Kyvik KO, Lathrop GM, Lawlor DA, Le BO, Lecoeur C, Li Y, Lyssenko V, Mahley R, Mangino M, Manning AK, Martinez-Larrad MT, McAteer JB, McCulloch LJ, McPherson R, Meisinger C, Melzer D, Meyre D, Mitchell BD, Morken MA, Mukherjee S, Naitza S, Narisu N, Neville MJ, Oostra BA, Orru M, Pakyz R, Palmer CN, Paolisso G, Pattaro C, Pearson D, Peden JF, Pedersen NL, Perola M, Pfeiffer AF, Pichler I, Polasek O, Posthuma D, Potter SC, Pouta A, Province MA, Psaty BM, Rathmann W, Rayner NW, Rice K, Ripatti S, Rivadeneira F, Roden M, Rolandsson O, Sandbaek A, Sandhu M, Sanna S, Sayer AA, Scheet P, Scott LJ, Seedorf U, Sharp SJ, Shields B, Sigurethsson G, Sijbrands EJ, Silveira A, Simpson L, Singleton A, Smith NL, Sovio U, Swift A, Syddall H, Syvanen AC, Tanaka T, Thorand B, Tichet J, Tonjes A, Tuomi T, Uitterlinden AG, van Dijk KW, van HM, Varma D, Visvikis-Siest S, Vitart V, Vogelzangs N, Waeber G, Wagner PJ, Walley A, Walters GB, Ward KL, Watkins H, Weedon MN, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Witteman JC, Yarnell JW, Zeggini E, Zelenika D, Zethelius B, Zhai G, Zhao JH, Zillikens MC DIAGRAM Consortium, GIANT Consortium, Global BPgen Consortium Borecki IB, Loos RJ, Meneton P, Magnusson PK, Nathan DM, Williams GH, Hattersley AT, Silander K, Salomaa V, Smith GD, Bornstein SR, Schwarz P, Spranger J, Karpe F, Shuldiner AR, Cooper C, Dedoussis GV, Serrano-Rios M, Morris AD, Lind L, Palmer LJ, Hu FB, Franks PW, Ebrahim S, Marmot M, Kao WH, Pankow JS, Sampson MJ, Kuusisto J, Laakso M (2010) New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet 42: 105–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie JE, Kumari M, Salo P, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M (2011) Sleep epidemiology--a rapidly growing field. Int J Epidemiol 40: 1431–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froy O (2011) The circadian clock and metabolism. Clin Sci 120: 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallicchio L, Kalesan B (2009) Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res 18: 148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, Perlis ML, Pack AI (2010) Problems associated with short sleep: bridging the gap between laboratory and epidemiological studies. Sleep Med Rev 14: 239–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter MJ, Hoover DR, Yu H, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, Manson JE, Howard BV, Wylie-Rosett J, Anderson GL, Ho GY, Kaplan RC, Li J, Xue X, Harris TG, Burk RD, Strickler HD (2008) Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, endogenous estradiol, and risk of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Res 68: 329–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JW, Yuen ST, Lam TH (2006) A case-control study on environmental and familial risk factors for colorectal cancer in Hong Kong: physical activity reduces colorectal cancer risk. Hong Kong Med J 12: 8–10 [Google Scholar]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) (2010) IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. In Shift-work, Painting and Fire-fighting. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyonvol. 98: 561–574 [Google Scholar]

- Kakizaki M, Inoue K, Kuriyama S, Sone T, Matsuda-Ohmori K, Nakaya N, Fukudo S, Tsuji I, Ohsaki CS (2008a) Sleep duration and the risk of prostate cancer: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 99: 176–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizaki M, Kuriyama S, Sone T, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Hozawa A, Nakaya N, Fukudo S, Tsuji I (2008b) Sleep duration and the risk of breast cancer: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 99: 1502–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Turek FW (2006) The U-shaped association between sleep and health: the 2 peaks do not mean the same thing. Sleep 29: 878–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolstad HA (2008) Nightshift work and risk of breast cancer and other cancers--a critical review of the epidemiologic evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health 34: 5–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Langer RD, Kline LE (2012) Hypnotics' association with mortality or cancer: a matched cohort study. BMJ Open 2: e000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine DW, Kripke DF, Kaplan RM, Lewis MA, Naughton MJ, Bowen DJ, Shumaker SA (2003) Reliability and validity of the Women’s Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess 15: 137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockley SW, Skene DJ, Arendt J (1999) Comparison between subjective and actigraphic measurement of sleep and sleep rhythms. J Sleep Res 8: 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R, Armitage R (1999) Sex, steroids, and sleep: a review. Sleep 22: 540–555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy JA, Newcomb PA, Titus-Ernstoff L, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Egan KM (2006) Duration of sleep and breast cancer risk in a large population-based case-control study. J Sleep Res 15: 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto FJ, Peppard PE, Young T, Finn L, Hla KM, Farre R (2012) Sleep disordered breathing and cancer mortality: results from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 190–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish JM (2009) Sleep-related problems in common medical conditions. Chest 135: 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Zhu X, Storfer-Isser A, Mehra R, Jenny NS, Tracy R, Redline S (2009) Sleep duration and biomarkers of inflammation. Sleep 32: 200–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, gurs-Collins T (1999) Measurement characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol 9: 178–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro SP, Schernhammer ES, Tworoger SS, Michels KB (2006) A prospective study on habitual duration of sleep and incidence of breast cancer in a large cohort of women. Cancer Res 66: 5521–5525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Helenius H, Irjala K, Polo O (1998) When does estrogen replacement therapy improve sleep quality? Am J Obstet Gynecol 178: 1002–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole EM, Schernhammer ES, Tworoger SS (2011) Rotating night shift work and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 934–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Kang TH, Reardon JT, Lee JH, Ozturk N (2010) Circadian clock control of the cellular response to DNA damage. FEBS Lett 584: 2618–2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Kawachi I, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA (2003) Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the nurses' health study. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 825–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sephton S, Spiegel D (2003) Circadian disruption in cancer: a neuroendocrine-immune pathway from stress to disease? Brain Behav Immun 17: 321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RG, Davis S (1996) The melatonin hypothesis: electric power and breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect 104(Suppl 1): 135–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El GF, Bouvard V, Altieri A, brahim-Tallaa L, Cogliano V (2007) Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol 8: 1065–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon SR, Luisi N, Balasubramanian R, Reeves KW (2012) Sleep duration and endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 23: 547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CL, Larkin EK, Patel S, Berger NA, Redline S, Li L (2011) Short duration of sleep increases risk of colorectal adenoma. Cancer 117: 841–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynes T, Hannevik M, Andersen A, Vistnes AI, Haldorsen T (1996) Incidence of breast cancer in Norwegian female radio and telegraph operators. Cancer Causes Control 7: 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkasalo PK, Lillberg K, Stevens RG, Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J (2005) Sleep duration and breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Res 65: 9595–9600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan AN, Schernhammer ES (2009) Circulating melatonin and the risk of breast and endometrial cancer in women. Cancer Lett 281: 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von RA, Weikert C, Fietze I, Boeing H (2012) Association of sleep duration with chronic diseases in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam study. PLoS One 7: e30972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welton AJ, Vickers MR, Kim J, Ford D, Lawton BA, MacLennan AH, Meredith SK, Martin J, Meade TW WISDOM team (2008) Health related quality of life after combined hormone replacement therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 337: a1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHI. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study (1998) The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials 19: 61–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PA, Yang X, Taber A, Oh EY, Ansell C, Ayers SE, Al-Assaad Z, Carnevale K, Berger FG, Pena MM, Hrushesky WJ (2008) Period 2 mutation accelerates ApcMin/+ tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res 6: 1786–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AH, Wang R, Koh WP, Stanczyk FZ, Lee HP, Yu MC (2008) Sleep duration, melatonin and breast cancer among Chinese women in Singapore. Carcinogenesis 29: 1244–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaggi HK, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB (2006) Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29: 657–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]