Abstract

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy worldwide, and in Canada, it is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men. The stratification of prostate cancer into risk categories has allowed for improved counselling of patients and provides guidance for treatment selection. However, the exact definition of high-risk prostate cancer remains controversial, and that lack of consensus remains a barrier to assessing available data from various institutions and from clinical trials. The proportion of patients with locally advanced high-risk disease has fallen in the last 20 years largely because of screening for prostate-specific antigen, but management in this population continues to be an important clinical problem. A factor that has emerged in recent years is the importance of local disease control, with data from multiple randomized trials suggesting that local therapy improves progression-free survival, disease-free survival, and overall survival. Further research in this population is necessary to improve outcomes.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, radiotherapy, locally advanced, local control

1. INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy, with 913,000 new cases and 215,000 deaths estimated worldwide in 20081. In the United States, prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men, and it is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death2.

Risk stratification systems are widely used to assist with patient counselling, to guide treatment selection risk, and to ensure prognostic uniformity in clinical trials and in the evaluation of treatment outcomes. Based on work by D’Amico et al., the Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada developed a classification system3,4 based on T category, prostate-specific antigen (psa) level at diagnosis, and Gleason score for patients with localized or locally advanced disease. In that system, high-risk disease is defined as the presence of any of cT3 or cT4 category, psa greater than 20 ng/mL, or Gleason score 8 or higher. That model has been demonstrated to be internally consistent and to accurately predict prostate cancer–specific mortality in patients treated with surgery or radiation therapy (rt)5,6. However, the exact definition of high-risk prostate cancer at diagnosis remains controversial, and that lack of consensus constitutes a barrier to comparisons of clinical outcomes in various institutional series and of the results of clinical trials (Table i). As a result, the patients studied in clinical trials of high-risk prostate cancer constitute a very heterogeneous group, including those having clinically organ-confined disease (cT1/T2), with a Gleason score of 8–10 or a psa level exceeding 20 ng/mL (or both), and those having locally advanced disease (cT3/T4).

TABLE I.

Definitions of high-risk prostate cancer

| Source | Definition |

|---|---|

| Genitourinary Radiation Oncologists of Canada4 | Clinical stage ≥ T3a OR Gleason score 8–10 OR psa ≥ 20 ng/mL |

| D’Amico et al., 19983 | Clinical stage ≥ T2c OR Gleason score 8–10 OR psa ≥ 20 ng/mL |

| Radiation Therapy Oncology Group7 | Clinical stage ≥ T2c OR Gleason score 8–10 AND psa < 100 ng/mL OR Any clinical stage AND Gleason score 8–10 AND psa 20–100 ng/mL |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network8 | Clinical stage ≥ T3 OR Gleason score 8–10 OR psa > 20 ng/mL OR Any two of

|

| European Association of Urology9 | Clinical stage ≥ T3 OR Gleason score 8–10 OR psa ≥ 20 ng/mL |

psa = prostate-specific antigen.

The proportion of patients presenting with locally advanced disease at diagnosis has declined since the early 1990s, largely as a result of widespread psa screening. However, this presentation remains a common clinical problem, and management remains controversial10. The term “high-risk locally advanced disease” has also been applied in the post-surgery setting to patients with pathologic T category T3 or T4. In the present article, we discuss the importance of achieving local disease control only in patients presenting with locally advanced disease (cT3/T4) at diagnosis and in those with pT3/T4 tumours after radical prostatectomy (rp).

2. PRESENTATION WITH CLINICALLY LOCALLY ADVANCED DISEASE

2.1. Primary Treatment with RT

External-beam rp (ebrt), even with dose escalation, used as monotherapy for patients with locally advanced disease has been shown not to be effective in locally advanced prostate cancer, and combined-modality treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (adt) is now the accepted treatment approach in this setting11.

In the landmark 22863 trial by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, overall survival and local control were considerably improved with the use of 3 years of adjuvant adt. An update of that trial with a median follow-up of 9.1 years confirmed the survival advantage for combination treatment, showing a 10-year overall survival of 58% in the combined-treatment group compared with 40% in the rt-only group. The proportion of patients with locally advanced disease in that trial was in the order of 90% in both arms12.

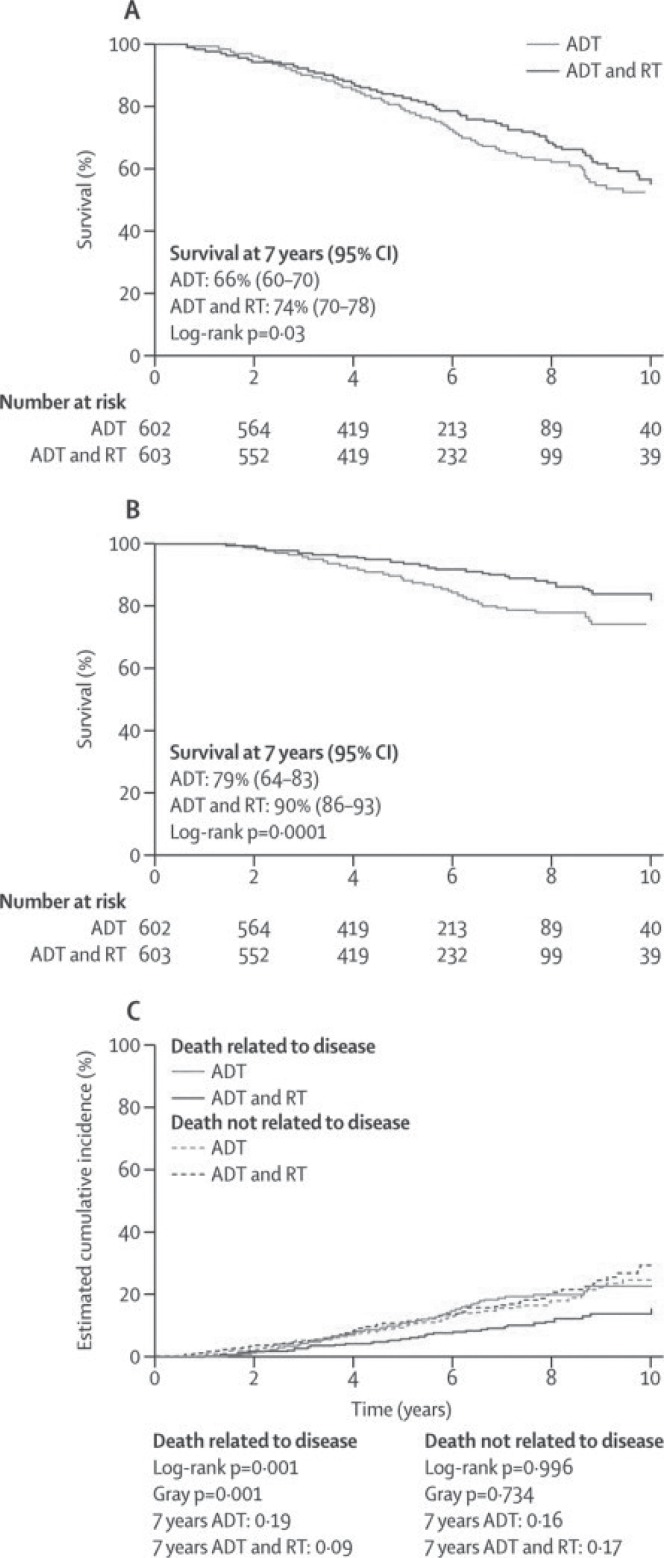

Three large randomized trials have now demonstrated the importance of local treatment and local control of tumour in improving outcomes in patients with locally advanced disease (Table ii). The ncic pr.3–U.K. Medical Research Council (mrc) PR07 study randomized 1205 patients with high-risk locally advanced disease to treatment with combined-modality therapy (rt and life-long adt) or to treatment with adt alone14. In excess of 85% of the patients had cT3/T4 disease. With a median follow-up of 6 years, combined-modality treatment resulted in a 23% reduction in overall mortality (Figure 1) and a 46% reduction in disease-specific mortality. A 70% reduction in disease progression was observed with the addition of rt, and local disease progression as a first manifestation of overall progression was reduced to 15% from 39%. The side effects of rt were of modest clinical magnitude, and serious long-term genitourinary or gastrointestinal toxicities from rt were uncommon. Patient-reported outcomes also showed that the negative impact of rt on bowel function was of modest clinical magnitude, with recovery by 36 months of scores tending to match those in patients not receiving rt.

TABLE II.

Randomized trials assessing the benefit of local radiotherapy (rt) in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (adt)

| Reference | Patients (n) | Median follow up (years) |

pfs adt vs. adt+rt |

dss adt vs. adt+rt |

os adt vs. adt+rt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widmark et al., 200913 | 875 | 7.6 | 26% vs. 75% p=0.0001 |

76% vs. 88% p<0.0001 |

61% vs. 70% |

| Warde et al., 201114 | 1205 | 6 |

hr: 0.3 95% ci: 0.23 to 0.39 p=0.001 |

hr: 0.54 95% ci: 0.27 to 0.78 p=0.0001 |

hr: 0.77 95% ci: 0.61 to 0.98 p=0.03 |

| Mottet et al., 201215 | 264 | 5.6 | 9% vs. 61% p<0.0001 |

86% vs. 93% p=0.0586 |

71.5% vs. 71.4%a |

Median overall survival not reached in either arm.

pfs = progression-free survival; dss = disease-specific survival; os = overall survival; hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval.

FIGURE 1.

Overall and disease-specific survival at 7 years in the pr.3 study. (A) Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival by treatment group. (B) Kaplan–Meier curve for disease-specific survival by treatment group. (C) Cumulative incidence of disease-specific survival. adt = androgen-deprivation therapy; rt = radiotherapy; ci = confidence interval. Reproduced, with permission, from The Lancet.

Similar data were reported by Widmark et al. in the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study 7 (spcg-7), in which 875 patients with prostate cancer were randomized to endocrine therapy alone or to endocrine therapy and ebrt13. With a median follow-up of 7.6 years, the cumulative incidence of prostate-cancer-specific mortality at 10 years was 23.9% in the endocrine-alone group and 11.9% in the endocrine plus rt group, for a relative risk of 0.44. At 10 years, the cumulative incidence for overall mortality was 39.4% in the endocrine-alone group and 29.6% in the endocrine plus rt group, for a relative risk of 0.6. Urinary, rectal, and sexual problems were slightly more frequent in the endocrine plus rt group. Approximately 80% of patients in the study had locally advanced disease. Although this trial—like the ncic pr.3–mrc PR07 study—addressed the issue of the effect of rt on survival, some differences between the studies were evident, with patients in the spcg-7 trial having a favourable prognosis. The maximum allowable psa for trial entry was 70 ng/mL. Patients with a psa exceeding 11 ng/mL were surgically staged, and those with positive pelvic nodes on histologic examination were excluded from the study. There were also some differences in treatment between the trials. In the spcg-7 study, total androgen blockade was administered for the first 3 months, and then antiandrogen therapy was given until progression or death. In the ncic pr.3–mrc PR07 study, hormonal therapy was adt, with lifelong luteinizing-hormone releasing-hormone analogue treatment or bilateral orchiectomy.

Mottet et al. recently reported the results of a randomized phase iii trial in which 264 patients, all with locally advanced disease, were randomized to adt alone for 3 years or to adt and ebrt15. With a median follow-up of 67 months, marked improvement in locoregional control was observed with the use of combined-modality therapy (90.2% vs. 70.8% with adt alone). There was also marked improvement in progression-free survival with the addition of ebrt (60.9% vs. 8.5% with adt alone). However, likely because of the small sample size, no improvement in overall survival has been seen to date.

The dose of rt used in those trials, 65–70 Gy, represented the standard of care in the 1990s when the trials were started. Since the late 1990s, the development of new rt techniques has allowed for a considerable increase in the rt dose, with acceptable morbidity, in patients with localized prostate cancer. Multiple clinical trials have shown an improvement in local control and improved freedom from relapse with higher doses of radiation16–18. It is therefore possible that the improvement in survival seen with the addition of rt to adt in the foregoing studies could be greater with the use of modern rt dose–fractionation schemes. Zelefsky et al., in a single-institution cohort study, demonstrated that local control, as assessed by post-treatment biopsies, is improved with the use of rt dose escalation19. Local tumour control was associated with a decrease in distant metastases and prostate cancer mortality—again emphasizing the importance of achieving optimal local control in these patients. In a number of recent studies, local recurrence of prostate cancer after ebrt has also been shown to occur predominantly at the site of the primary tumour before treatment, suggesting that supplementary focal therapy to the dominant primary tumour might also improve outcomes20,21.

Although dose-escalation techniques with megavoltage ebrt have evolved greatly in recent years, rectal dose constraints limit the total dose of rt that can be given using this strategy. That problem makes brachytherapy—usually in combination with ebrt as a form of dose escalation—an attractive option.

For 1342 men with high-risk prostate cancer, D’Amico et al. reported the risk of prostate cancer–related mortality after brachytherapy alone or in combination with adt, ebrt, or both22. Men who received brachytherapy and both adt and ebrt were significantly more likely to have multiple high-risk factors, and yet a significant reduction in prostate cancer mortality was observed in that cohort [hazard ratio (hr): 0.32; 95% confidence interval (ci): 0.14 to 0.73; p = 0.0006]. However, the proportion of patients with cT3/T4 disease in the trial was only 12%. A retrospective analysis from a Swedish group (Aström et al.23) of 214 consecutive patients treated with ebrt (50 Gy in 25 fractions) and high-dose-rate brachytherapy (two 10-Gy fractions) reported their results after a median follow-up of 48 months. In the high-risk group of 47 patients (32 with cT3/T4 disease), the 5-year biochemical no evidence of disease rate was 61%. A randomized trial by Sathya et al.24 compared the efficacy of an iridium implant plus ebrt with ebrt alone in patients with T2/T3 disease. Of the 104 patients randomized (40% with cT3 disease), 51 received an iridium implant of 35 Gy delivered to the prostate over 48 hours, plus 40 Gy ebrt delivered at 2 Gy per fraction over 4 weeks, and 54 received ebrt alone (66 Gy in 33 fractions). At a median follow up of 8.2 years, the rates of biochemical failure were 29% in the implant plus ebrt group and 61% in the ebrt-alone group. Local control was also better in the combined-treatment group (51% vs. 24%).

Although dose escalation using brachytherapy in locally advanced disease is a reasonable strategy, the data are currently insufficient to recommend that approach outside of a clinical research setting.

2.2. Primary Treatment with Surgery

In the past, rp was not considered an acceptable treatment approach in patients with locally advanced disease. However, because of improvements in surgical techniques, rp is now increasingly being used in selected patients with cT3a disease. Table iii lists the results of series investigating the primary use of surgery in this setting. Stephenson et al.28 reported the results of 6398 patients with prostate cancer treated with rp at the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center and Baylor College of Medicine. Of that group, only 4% (n = 254) had cT3/T4 disease. The 15-year prostate cancer–specific mortality was 38% for those patients.

TABLE III.

Outcomes for high-risk prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy

| Reference | Patients (n) | Median follow-up |

10-Year survival (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical recurrence–free | Prostate cancer–specific | Overall | |||

| Ward et al., 200525 | 841a | 10.3 years | 43 | 90 | 76 |

| Yossepowitch et al., 200726 | 957b | 46 months | 59 | ||

| Zwergel et al., 200727 | 275 | 42 months | 25c | 83 | 70 |

| Stephenson et al., 200928 | 1962 | 48 months | 92 | ||

| Spahn et al., 201029 | 712 | 77 months | 52 | 90 | 74 |

Results for patients with cT3 disease.

Results for cohort of patients using definition of high risk from D’Amico et al., 19983.

With deferred hormonal therapy.

The guidelines from the European and American associations of urology for the management of locally advanced disease suggest that an extended lymph node dissection be performed at the time of rp. Whether that procedure is just for staging or has any therapeutic value is controversial, and that question is currently being addressed in a randomized trial in Germany. Furthermore, patients with advanced disease undergoing rp would need to be advised that they have a risk of possible further adjuvant therapy in the form of rt with or without hormonal therapy. The possible value of local therapy in the form of prostatectomy, even in lymph-node-positive patients, was addressed by Engel et al.30, who used the Munich cancer registry to compare outcomes for patients with positive lymph nodes in whom rp was completed and for those in whom prostatectomy was abandoned. Among 1413 patients, prostatectomy was aborted in 456 with lymph-node-positive disease; in the remaining 957 patients, the prostatectomy was completed. At 28% versus 64%, 10-year survival was inferior for patients who did not undergo rp. Those results show a survival benefit for local treatment even in lymph-node-positive disease and therefore suggest that local control may result in improved outcomes overall. However, given the inherent bias in the study (the greater potential for prostatectomy abandonment in patients having unresectable and therefore more advanced disease), the results must be viewed with caution.

The use of adjuvant adt has not been shown to improve outcomes, except in the case of a small randomized trial by Messing et al.31, in which 98 patients with node-positive disease were randomized to receive observation or adjuvant hormonal therapy. However, the relevance of that study in contemporary practice is unclear, because the trial was started in the pre-psa era and adt was therefore given only at clinical progression.

Because of the highly selected nature of patients whose primary management was surgery, it is not possible to comment on the efficacy of that approach. Certainly, when used in selected patients and combined with adjuvant rt, surgery does achieve good local control. However, whether the additional morbidity associated with the use of combined treatment improves overall outcome is unknown at this time.

3. PRESENTATION WITH LOCALLY ADVANCED DISEASE AFTER RP

3.1. Role of Adjuvant RT

About 20% of patients who undergo rp for localized disease experience a biochemical relapse. Three randomized controlled trials have all showed a benefit for adjuvant rt in men with pathologically advanced cancer (pT3 disease with extracapsular extension, positive surgical margins, or seminal vesicle invasion).

The Southwest Oncology Group 8794 study randomized 425 men with pT3 disease to adjuvant radiotherapy (60–64 Gy) or to observation32. Of the 211 men randomized to observation, 70 received salvage rt. With a median follow-up of more than 12 years, adjuvant rt was associated with significant improvements in metastasis-free survival (hr: 0.71; p = 0.016) and overall survival (hr: 0.7; p = 0.023).

Similarly, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 22911 trial randomized 1005 patients with pT3 disease to immediate postoperative rt of 60 Gy or to a wait-and-see policy33. With a median follow-up of 5 years, adjuvant rt was associated with an improvement in biochemical progression-free survival (74% vs. 52.6%, p < 0.0001). Updated results for that trial revealed that, after a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the 10-year biochemical progression-free survival was 60% in the rt arm compared with 40% in the observation arm. A reduction in locoregional failure to 7.3% from 16.6% with rt was also reported (p < 0.0001). Longer follow-up is necessary to determine whether those benefits will translate into an overall survival benefit.

The aro 96-02 study randomized 388 patients with pT3 disease to observation or to immediate postoperative rt34. By protocol design, 78 patients with persistently elevated psa after prostatectomy were excluded from the intention-to-treat analysis. Results were reported for 307 patients (159 in the observation arm, 148 in the adjuvant rt arm). Results favoured rt, with a 5-year progression-free survival of 54% in patients receiving adjuvant rt compared with 72% in patients in the observation arm (p = 0.0002).

All three trials provide strong evidence to support the importance of achieving local control of disease in patients with locally advanced disease after surgery. Whether there is a benefit of adjuvant compared with early salvage rt in the era of ultrasensitive psa testing is currently being tested in a large multicentre clinical trial—radicals35.

4. DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY

The importance of achieving local control in patients presenting with locally advanced prostate cancer is not surprising. Similar data are available for other cancers. Data for adjuvant rt to the breast in women who have had breast-conserving surgery and for post-mastectomy rt showed that the addition of rt led to an improvement in locoregional control and overall survival36,37. However, this comparison has been somewhat confusing in prostate cancer because of the competing risks for mortality in this group of patients (attributable to age at presentation) and also because of the difficulty in ascertaining local control. The mature level 1 evidence from multiple randomized trials that is now available shows that improved local control in this setting improves overall and disease-specific survival. The final analysis of the ncic pr.3–mrc PR07 study confirms the substantial benefit for the use of local treatment in the management of these patients. Data showing the benefit of local therapy (adjuvant rt after surgery in high-risk postoperative patients) also points to the importance of achieving local control of disease. The role of focal rt in this setting—either with high-dose-rate or interstitial brachytherapy—needs to be explored, as does the role of surgery, possibly with the use of preoperative ebrt (as routinely used in locally advanced rectal cancer). Only by accruing patients to prospective randomized trials will all of these issues be addressed.

5. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

6. REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: globocan 2008. Int J Cancer. 2008;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukka H, Warde P, Pickles T, Morton G, Brundage M, Souhami L, on behalf of the Canadian GU Radiation Oncologist Group Controversies in prostate cancer radiotherapy: consensus development. Can J Urol. 2001;8:1314–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chism DB, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Feigenberg SJ, Pollack A. A comparison of the single and double factor high-risk models for risk assignment of prostate cancer treated with 3D conformal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:380–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Amico AV, Cote K, Loffredo M, Renshaw AA, Schultz D. Determinants of prostate cancer specific survival following radiation therapy during the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol. 2003;170:S42–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000094800.63501.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roach M, Lu J, Pilepich MV, et al. Four prognostic groups predict long-term survival from prostate cancer following radiotherapy alone on radiation therapy oncology group clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:609–15. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, et al. nccn clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. eau guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol. 2011;59:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooperberg MR, Moul JW, Carroll PR. The changing face of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8146–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastian PJ, Boorjian SA, Bossi A, et al. High-risk prostate cancer: from definition to contemporary management. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1096–106. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolla M, Van Tienhoven G, Warde P, et al. External irradiation with or without long-term androgen suppression for prostate cancer with high metastatic risk: 10-year results of an eortc randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1066–73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widmark A, Klepp O, Solberg A, et al. on behalf of the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study 7. Swedish Association for Urological Oncology 3 Endocrine treatment, with or without radiotherapy, in locally advanced prostate cancer (spcg-7/sfuo-3): an open randomised phase iii trial. Lancet. 2009;373:301–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warde P, Mason M, Ding K, et al. Combined androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:2104–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61095-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mottet N, Peneau M, Mazeron JJ, Molinie V, Richaud P. Addition of radiotherapy to long-term androgen deprivation in locally advanced prostate cancer: an open randomised phase 3 trial. Eur Urol. 2012;62:213–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zietman AL, Bae K, Slater JD, et al. Randomized trial comparing conventional-dose with high-dose conformal radiation therapy in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate: long-term results from Proton Radiation Oncology Group/American College of Radiology 95-09. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1106–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.8475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuban DA, Tucker SL, Dong L, et al. Long-term results of the M.D. Anderson randomized dose escalation trial for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peeters ST, Heemsbergen WD, Koper PC, et al. Dose–response in radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: results of the Dutch multicenter randomized phase iii trial comparing 68 Gy of radiotherapy with 78 Gy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1990–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelefsky MJ, Reuter VE, Fuks Z, Scardino P, Shippy A. Influence of local tumor control on distant metastases and cancer related mortality after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008;179:1368–73. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chopra S, Toi A, Taback N, et al. Pathological predictors for site of local recurrence after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arrayeh E, Westphalen AC, Kurhanewicz J, et al. Does local recurrence of prostate cancer after radiation therapy occur at the site of primary tumor? Results of a longitudinal mri and mrsi study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e787–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Amico AV, Moran BJ, Braccioforte MH, et al. Risk of death from prostate cancer after brachytherapy alone or with radiation, androgen suppression therapy, or both in men with high-risk disease. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3923–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aström L, Pedersen D, Mercke C, Holmäng S, Johansson KA. Long-term outcome of high dose rate brachytherapy in radiotherapy of localised prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2005;74:157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sathya JR, Davis IR, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial comparing iridium implant plus external-beam radiation therapy with external-beam radiation therapy alone in node-negative locally advanced cancer of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1192–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward JF, Slezak JM, Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Zincke H. Radical prostatectomy for clinically advanced (cT3) prostate cancer since the advent of prostate-specific antigen testing: 15-year outcome. BJU Int. 2005;95:751–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yossepowitch O, Eggener SE, Bianco FJ, et al. Radical prostatectomy for clinically localized, high risk prostate cancer: critical analysis of risk assessment methods. J Urol. 2007;178:493–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zwergel U, Suttmann H, Schroeder T, et al. Outcome of prostate cancer patients with initial psa> or =20 ng/mL undergoing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1058–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson AJ, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, et al. Prostate cancer–specific mortality after radical prostatectomy for patients treated in the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4300–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spahn M, Joniau S, Gontero P, et al. Outcome predictors of radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL: a European multi-institutional study of 712 patients. Eur Urol. 2010;58:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engel J, Bastian PJ, Baur H, et al. Survival benefit of radical prostatectomy in lymph node-positive patients with prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2010;57:754–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messing EM, Manola J, Yao J, et al. on behalf of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study est 3886 Immediate versus deferred androgen deprivation treatment in patients with node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:472–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Paradelo J, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathological T3N0M0 prostate cancer significantly reduces risk of metastases and improves survival: long-term followup of a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2009;181:956–62. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolla M, Van Poppel H, Collette L, et al. Post operative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial (eortc 22911) Lancet. 2005;366:572–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiegel T, Bottke D, Steiner U, et al. Phase iii postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy compared with radical prostatectomy alone in pT3 prostate cancer with postoperative undetectable prostate-specific antigen: aro 96- 02/auo ap 09/95. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2924–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker C, Catton CN, Sydes MR, et al. radicals—an Intergroup randomised controlled trial in prostate cancer of optimal timing of radiotherapy and duration of hormone therapy after radical prostatectomy (mrc PR10, ncic pr.13) [abstract 407] Am Soc Clin Oncol Prostate Cancer Symp. 2007. [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=46&abstractID=20285; cited October 31, 2012]

- 36.Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, et al. on behalf of Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (ebctcg) Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:1707–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Recht A, Edge SB, Solin LJ, et al. on behalf of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Postmastectomy radiotherapy: clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1539–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]