Abstract

Objective

In rats transgenic for human HLA–B27 and β2-microglobulin (B27-transgenic rats), colitis and peripheral inflammation develop spontaneously. Therefore, B27-transgenic rats provide a model of spondylarthritis. Because inflammation in these rats requires CD4+ T lymphocytes and involves intestinal pathology, we hypothesized that dendritic cells (DCs) that migrate from the intestine and control CD4+ T cell differentiation would be aberrant in B27-transgenic rats.

Methods

Migrating intestinal lymph DCs were collected via thoracic duct cannulation from B27-transgenic and control (HLA–B7–transgenic or nontransgenic) rats. The phenotypes of these DCs and of mesenteric lymph node DCs were assessed by flow cytometry. The ability of DCs to differentiate from bone marrow precursors in vitro was also assessed.

Results

Lymph DCs showed increased activation and, strikingly, lacked the specific DC population that is important for maintaining tolerance to self-antigens. This population of DCs was also depleted from the mesenteric lymph nodes of B27-transgenic rats. Furthermore, in vitro culture of DCs from bone marrow precursors revealed a defect in the ability of B27-transgenic rats to produce DCs of the migratory phenotype, although the DCs that were generated induced enhanced interleukin-17 (IL-17) production from naive CD4+ T cells.

Conclusion

We describe 2 different mechanisms by which HLA–B27 may contribute to inflammatory disease: increased apoptotic death of B27-transgenic DCs that normally function to maintain immunologic tolerance and enhanced IL-17 production from CD4+ T cells stimulated by the surviving B27-transgenic DCs.

The spondylarthritides (SpAs) are a group of interrelated disorders with common genetic predisposing factors. Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is the prototype disease in this group; other entities include reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and arthritis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). SpA affects axial and peripheral joints, entheses, skin (psoriasis), gut (IBD), and eyes (uveitis). Genetic factors are thought to account for most of the disease susceptibility, and expression of the class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) gene HLA–B27 is strongly associated with the development of SpA (1). However, the mechanisms by which HLA–B27 causes pathology are unclear. Transgenic rats expressing the human HLA–B*2705 and human β2-microglobulin (β2m) genes (B27-transgenic rats) provide an animal model for SpA, and much of what is known about the role of HLA–B27 has been revealed using this model. In B27-transgenic animals, inflammatory disease resembling human SpA develops spontaneously and is characterized by peripheral arthritis, psoriasis, and colitis (2). Animals transgenic for human β2m and another human class I MHC allele, HLA–B*0702, do not display any overt inflammation and are useful controls (3).

Dendritic cells (DCs) drive the differentiation of naive T cells. They initiate protective T cell responses against pathogens and help prevent damaging auto-immune responses by inducing mechanisms collectively described as self-tolerance (4). DC precursors, which develop in bone marrow, differentiate in secondary lymphoid organs or somatic tissue. Migratory DCs traffic constitutively from tissue to lymph nodes (LNs) via lymph (5) and are essential for initiating immune responses against pathogens and self antigens (6-8).

Several lines of evidence indicate that DCs may be involved in the initiation of SpA. For instance, disease development in B27-transgenic rats relies on HLA–B27 expression on bone marrow–derived cells (9) and on CD4+ T cells (10), which require DCs for their activation and differentiation. Abnormal interactions also occur between B27-transgenic DCs and T cells (11, 12). Furthermore, recent data have implicated several DC-expressed genes (IL23R, ERAP1, RUNX3, IL12B) in increased susceptibility to the development of AS (13, 14). There is also evidence for a causal connection between the intestinal symptoms associated with SpA and systemic inflammation. For example, B27-transgenic animals do not experience joint or intestinal inflammation when they are raised in the absence of commensal intestinal bacteria (15, 16). Also, a lack of intestinal inflammation in patients with AS indicates a good prognosis (17).

We therefore hypothesized that HLA–B27 expression would contribute to disease by altering the functions of migrating intestinal DCs. These cells can be purified from the thoracic duct lymph of rats after mesenteric lymphadenectomy (18, 19) and can be identified by their expression of CD103 (20). We investigated the CD103+ DCs of B27-transgenic rats and demonstrated that a specific population of migratory DCs is depleted from intestinal lymph, mesenteric LNs (MLNs), and DCs grown from bone marrow precursors. The remaining bone marrow–derived DCs preferentially induce interleukin-17 (IL-17) production from CD4+ T cells. These changes may contribute to the development of inflammatory disease in these rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

HLA–B*2705–transgenic rats of founder line 33-3 (B27-transgenic) on a Fischer background (F344/NTac-Tg[HLA–B2705, â2M]33-3Trg) (Taconic) were bred under license. F344 HLA–B*0702–transgenic rats (B7-transgenic) of the 120-4 line, were obtained from Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France. B27-transgenic and B7-transgenic rats were back-crossed with PVG rats (strain PVG/OlaHsd; Harlan) for a minimum of 3 generations before being used in the experiments. The backcross generations for each experiment were as follows: for histology, B27-transgenic (N5); for lymph, B27-transgenic (N3–N6) and B7-transgenic (N3); for MLNs, B27-transgenic (N10) and B7-transgenic (N5); for bone marrow-derived DCs, B27-transgenic (N8 or greater).

All offspring were screened for the expression of HLA–B27 or HLA–B7, using flow cytometry. Age-matched nontransgenic littermates were used as controls. DA rats were purchased from Harlan. All rats were used at the age of 8-14 weeks, unless otherwise stated. The rats were maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions at the University of Glasgow. All procedures were approved by the University of Glasgow Ethical Review Panel and were performed under licenses from the UK Home Office.

Collection of tissue and cells

Tissue specimens were immediately fixed in neutral buffered formalin. They were then dissected, paraffin-embedded, sectioned (5 μm), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were obtained using a light microscope with a 10× objective and analyzed using cell^B software (Olympus).

Lymph was collected from male rats using previously described methods (21, 22). Briefly, mesenteric lymphadenectomy was performed on 5–6-week-old rats. At least 5 weeks later, a 3Fr cannula (Harvard Apparatus) was inserted into the thoracic duct at the time of laparotomy. Lymph was collected for up to 48 hours.

Mesenteric LNs were harvested in serum-free RPMI and digested using Liberase (0.4 Wünsch units/ml; Roche) and DNase (50 μg/ml; Roche). Single-cell suspensions were generated by filtering digested tissue through a 40-μm cell strainer (Becton Dickinson).

Flow cytometry

Cells were either stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies or with biotinylated antibodies and fluorochrome-labeled streptavidin. The cells were then extensively washed and analyzed using a MACSQuant analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec) or an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). A FACSAria instrument (Becton Dickinson) was used for flow cytometric sorting.

Fluorochrome-labeled reagents included the following: phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated annexin V (Becton Dickinson), HLA–B7 (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]–conjugated BB7.1; Serotec), HLA–B27 (FITC-conjugated HLA–A/B/C-m3; Serotec), class II MHC (PerCP-conjugated OX6; Becton Dickinson), CD4 (allophycocyanin-conjugated OX35; Becton Dickinson), CD11b (PE-conjugated OX42; Becton Dickinson), CD25 (PE-conjugated OX39; Becton Dickinson), CD80 (PE-conjugated B7-1; Becton Dickinson), and CD86 (PE-conjugated B7-2; Serotec). The following biotinylated lineage markers were used: CD45RC (OX22; BioLegend), CD45RA (OX33; BioLegend), Igκ light chain (OX12; conjugated in house), and T cell receptor α/β (R73; conjugated in house). Antibodies specific for CD103 (OX62), CD172a (OX41), T cell receptor α/β, and OX12 were obtained from Prof. Neil Barclay (Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford, UK). The antibodies were conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen), or biotin (Thermo Scientific). Dead cells were identified using DAPI (Molecular Probes).

Mixed lymphocyte reactions

Mixed lymphocyte reactions were performed as previously described (22). Briefly, flow-sorted class II MHC–positive CD103+ lymph DCs from B27-transgenic PVG (RT1c) rats were cultured for 5 days with 1 × 105 cells from the LNs of DA (RT1av1) rats. For bone marrow–derived DC mixed lymphocyte reactions, live class II MHC–positive CD103+ cells were flow sorted and cultured for 5 days with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–stained 1 × 105 flow-sorted CD4+CD25−CD45RC+ naive T cells. Two methods were used to assess T cell proliferation. For lymph DCs, 3H-thymidine was added for the final 12 hours of culture, after which the cultures were harvested onto filter mats and analyzed with a scintillation counter. For bone marrow–derived DCs, T cells were labeled with CFSE, and proliferating cells were identified by flow cytometry. Immediately before harvesting of the bone marrow-derived DC/T cell cocultures, samples of supernatant were harvested, and the concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and interferon-γ (IFNγ) were measured by Luminex assay (BioLegend).

Bone marrow cultures

Bone marrow cells were harvested, and red blood cell–free cell suspensions were cultured for 7 days in RPMI 1640 with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (all from Invitrogen). Cultures were supplemented with mouse Flt-3 ligand [Flt-3L]) prepared in-house. Some cultures were also supplemented with granulocyte–macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 100 ng/ml) or Q-VD-OPh (Q-VD) (both from R&D Systems). On occasion, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium lipopolysaccharide(LPS)(Invivo-Gen) overnight before harvesting.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test or analysis of variance was used to test for statistically significant differences between populations. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. GraphPad Prism software was used for the analyses.

RESULTS

To test the hypothesis that migrating intestinal DCs are altered in B27-transgenic rats, we examined lymph DCs collected by thoracic duct cannulation (TDC) (23, 24). This technique is the best manner in which to obtain bona fide migrating DCs.

Symptoms of intestinal inflammation in B27-transgenic PVG rats

First, we evaluated the suitability of available B27-transgenic rats on a F344 background for TDC. Unfortunately, the microanatomy of the lymph duct in these rats renders them unsuitable for this procedure (data not shown). B27-transgenic rats have previously been crossed onto both PVG and Lewis rat strains, both of which develop spontaneous inflammatory disease (ref. 25, and Taurog J: personal communication). Our previous TDC procedures using Lewis rats had a lower success rate (Milling S: unpublished data). We therefore crossed B27-transgenic F344 rats with wild-type PVG rats to obtain B27-transgenic PVG rats from which we could reliably acquire lymph.

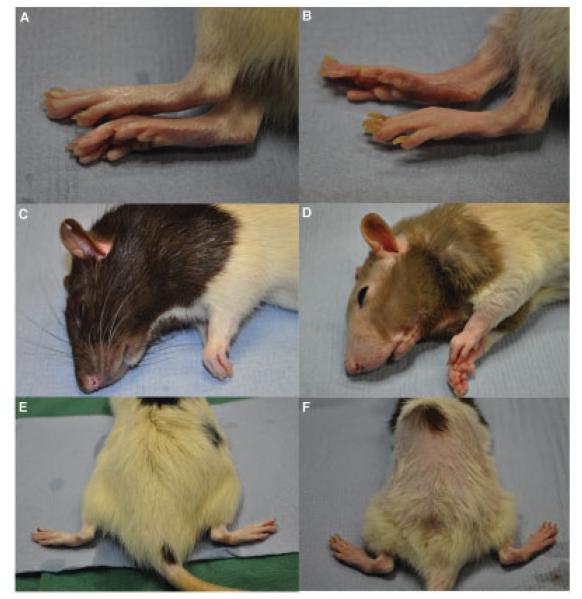

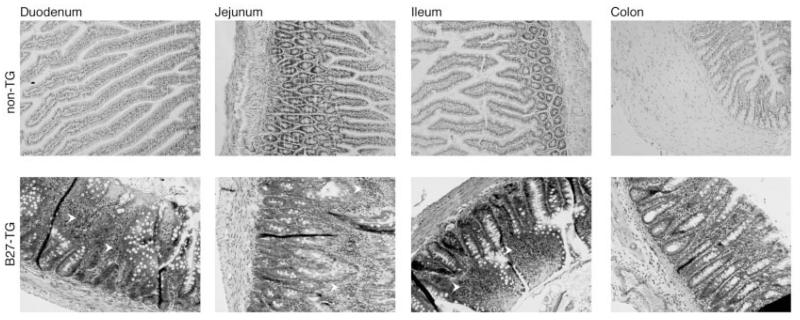

We observed the B27-transgenic PVG rats to determine whether they acquired symptoms of inflammation. Like B27-transgenic F344 rats, B27-transgenic PVG rats experienced mild diarrhea. On occasion, when rats were maintained in our colony for longer periods, nail deformities, hair loss, and reddening of the paws were observed (Figure 1). Arthritis has been observed to occur in 25–30% of B27-transgenic PVG rats, beginning after 14 weeks of age (Taurog J: personal communication). We characterized intestinal disease in the B27-transgenic PVG rats. Consistent with previous observations (3), our analysis of 15-week-old B27-transgenic rats revealed inflammation in the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Systemic disease in HLA–B27–transgenic rats on a PVG background. B27-transgenic rats were backcrossed to a PVG background for >10 generations. Representative images of the hind feet, head, and back of wild-type rats (A, C, and E) and 4-week-old B27-transgenic rats (B, D, and E) are shown. The B27-transgenic rats clearly displayed nail dystrophy, hair loss on the head and back, and reddening of the feet.

Figure 2.

Presence of inflammation in the intestines of HLA–B27–transgenic (B27-TG) rats on a PVG background. Intestinal tissue specimens from nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats were obtained under terminal anesthesia and fixed in formalin. Fixed specimens were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. B27-transgenic rats had shortened, inflamed villi in duodenal, jejunal, and ileal sections. Inflammatory infiltrates were observed in the lamina propria throughout the small intestine of B27-transgenic rats (arrowheads).

Fewer lymph DCs in B27-transgenic rats

B27-transgenic PVG rats were used for all experiments, together with nontransgenic littermates and B7-transgenic rats, which also were backcrossed onto a PVG background. Lymph was collected from individual rats for 24-hour periods. Samples were analyzed either 24 hours after cannulation (day 1; 0–24 hours) or 48 hours after cannulation (day 2; 24–48 hours). Lymph DCs had high expression of CD103 and class II MHC (24, 26, 27) (Figure 3A).

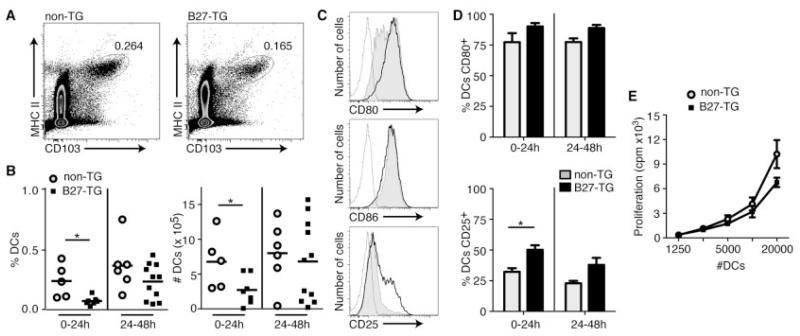

Figure 3.

Characteristics of dendritic cells (DCs) migrating from the intestine of HLA–B27–transgenic (B27-TG) rats. Thoracic duct lymph was collected from nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats and analyzed by flow cytometry. A, DCs were identified by their expression of CD103 and class II major histocompatibility complex (MHCII). Lymph was collected for 24 hours, either immediately after cannulation (0–24 hours) or for the subsequent 24 hours (24–48 hours). Both the percentage and the absolute number of DCs from each rat were calculated. Values are the percent total cells represented by DCs. B, Data for multiple nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats at both time points were compiled and analyzed. Bars show the mean. C, Representative histograms with gating of DCs stained for CD80, CD86, or CD25 from nontransgenic rats (shaded), B27-transgenic rats (thick line), or isotype controls (thin line) are shown. D, CD80 and CD25 data for multiple nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats at 0–24 hours and 24–48 hours were pooled and compared. Bars show the mean ± SEM. * = P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. E, Allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reactions using flow-sorted lymph DCs from B27-transgenic rats and nontransgenic littermates were performed. Proliferation was measured by incorporation of 3H-thymidine after 5 days. Values are the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells for DCs from nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats; the results are representative of 5 experiments.

B27-transgenic rats ages 10–14 weeks had significantly fewer lymph DCs during the first 24-hour collection period (day 1) compared with nontransgenic rats (Figure 3B). A similar trend was observed during the second 24-hour collection period (day 2), but the difference between the 2 groups was not statistically significant (Figure 3B). The mean proportions of lymph DCs, calculated for a minimum of 3 cannulation experiments, were similar in lymph from nontransgenic rats and B7-transgenic rats (additional information is available from the corresponding author).

More-activated phenotype in lymph DCs from B27-transgenic rats

A hallmark of DCs is their sensitivity to their environment; inflammation mediators activate DCs in vitro and in vivo (28-30). Because the intestine of B27-transgenic rats is inflamed, we predicted that lymph DCs would be activated. We therefore analyzed lymph DC expression of costimulatory molecules CD80, CD86, and CD25, which is the most sensitive marker of activation on rat DCs (31) (Figure 3C). When we compared B27-transgenic rats with nontransgenic rats, we observed no significant differences in CD80 or CD86 expression (Figures 3C and D). However, expression of CD25 was significantly increased on a proportion of lymph DCs from B27-transgenic rats at 0–24 hours (Figure 3D). A similar pattern of CD25 expression was observed during the second 24-hour collection period, but the difference between the 2 groups was not statistically significant (Figure 3D).

Similar ability of B27-transgenic and nontransgenic lymph DCs to induce allogeneic T cell proliferation

The primary function of DCs is to induce proliferation and differentiation of T cells in LNs (32). CD103+ class II MHC–positive lymph DCs drive proliferation and differentiation of allogeneic naive CD4+ T cells (27). We performed allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reactions using flow-sorted lymph DCs from B27-transgenic rats and nontransgenic littermates on 5 independent occasions. As shown in a representative experiment (Figure 3E), neither lymph DC population consistently displayed an enhanced ability to stimulate proliferation.

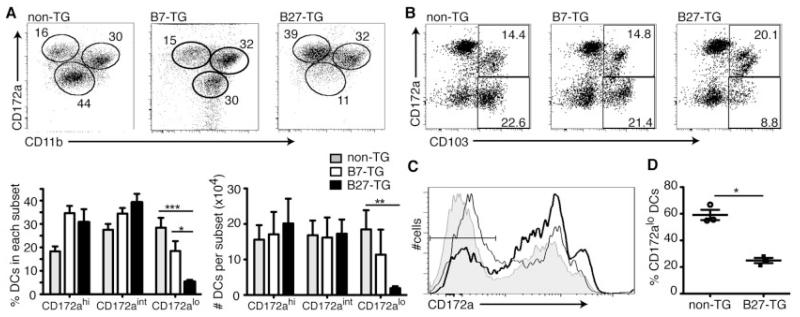

Absence of a subset of migrating lymph DCs in B27-transgenic rats

Lymph DCs can be categorized into 3 functionally discrete subsets (24). These subsets are described as CD172ahighCD11blow (CD172ahigh), CD172intermediateCD11b+ (CD172aintermediate), and CD172alowCD11bintermediate (CD172alow). We examined lymph DCs from B27-transgenic rats and nontransgenic littermates at 0-24 hours. B27-transgenic rats had fewer CD172alow lymph DCs, as a proportion of lymph cells and in absolute numbers, compared with nontransgenic and B7-transgenic rats (Figure 4A). Although the proportion of CD172ahigh and CD172aintermediate lymph DCs in B27-transgenic rats was higher than that in nontransgenic rats, the numbers of cells in these lymph DC subsets did not increase (Figure 4A). The same statistically significant pattern was observed at 24–48 hours (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Absence of a population of migratory DCs in B27-transgenic rats. Thoracic duct lymph was collected from nontransgenic, B7-transgenic, and B27-transgenic rats and analyzed by flow cytometry. A, Class II MHC–positive CD103+ cells were analyzed for their expression of CD172a and CD11b. Values in the dot plots are percentages. The experiment was repeated 3 times, and both the percentage and the absolute numbers of DCs in each subset were calculated. Bars show the mean ± SEM. B, Mesenteric lymph nodes were collected from nontransgenic, B7-transgenic, and B27-transgenic rats, and the proportion of CD172a− cells within the class II MHC–positive CD103+ lineage–negative (T cell receptor α/β−, CD45RA−, Igκ− CD45RC−) cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Values in the dot plots are percentages. C and D, Flow cytometric analysis was performed to determine the number (C) and percent (D) of CD172a− cells. A representative histogram shows the expression of CD172a in CD103+ cells from nontransgenic rats (shaded), B7-transgenic rats (thin line), and B27-transgenic rats (thick line) (C). The percentages of CD172a− cells, as gated in C, from 3 individual experiments were compared (D). Data in A were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Data in D were analyzed by Student’s t-test. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001. See Figure 3 for other definitions.

We next sought to determine whether the absence of a subset of migrating lymph DCs was reflected in MLNs, which are the normal destination for lymph DCs. Consistent with the lymph data, B27-transgenic rats at 10–16 weeks of age had a significantly smaller proportion of CD103+ CD172alow MLN DCs compared with nontransgenic littermates and age-matched B7-transgenic rats (Figures 4B–D). In 6-week-old rats, before the onset of symptoms of inflammation, we observed a similar loss of CD103+CD172alow DCs (additional information is available from the corresponding author). This loss of CD172alowCD103+ MLN DCs was not associated with any increase in the number of CD172a+CD103+ DCs in MLNs (data not shown).

Consistent with previous findings from our laboratory (33), we observed a significantly reduced level of class II MHC expression on CD103+ DCs in MLNs. A similar trend was observed on CD103+ lymph DCs, but the difference did not reach significance. All of the DCs in B27-transgenic MLNs expressed HLA–B27 (additional information is available from the corresponding author).

As described above, the proportion of CD172alow DCs was lower in the lymph and MLNs of B27-transgenic rats compared with those of B7-transgenic rats and nontransgenic littermates, indicating an HLA–B27–associated loss of the migratory CD172alow subset of intestinal DCs from B27-transgenic rats.

Apoptotic death of B27-transgenic Flt-3L–supplemented bone marrow–derived DCs

We hypothesized that the effects of the transgene on DCs might not be confined to the intestinal compartment. We therefore examined bone marrow–derived DCs to determine whether the defect was systemic. Bone marrow-derived DCs cultured with the growth factor Flt-3L resemble steady-state migrating DC populations more closely than those cultured with GM-CSF (34).

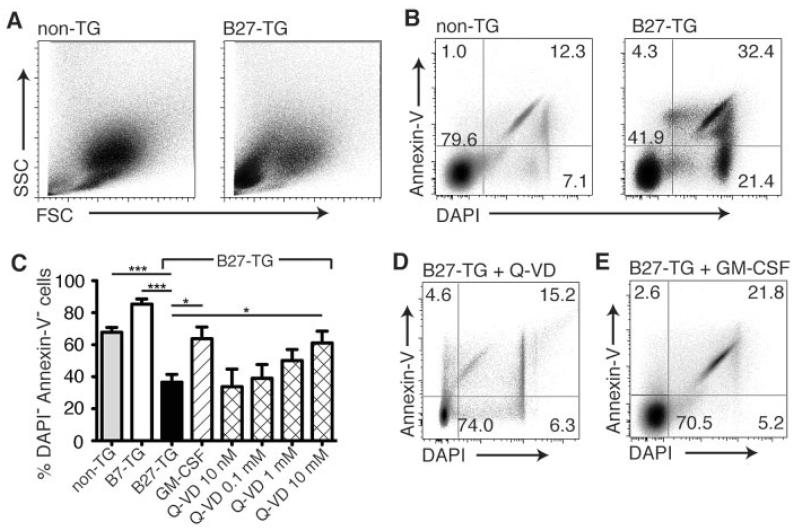

When bone marrow cells from rats at 8–14 weeks of age were cultured for 7 days with mouse Flt-3L, we observed that cultures of DCs from B27-transgenic rats contained a higher proportion of small granular cells (Figure 5A). We also observed a significantly lower proportion of live (annexin V–negative/DAPI-negative) cells in cultures of B27-transgenic rat bone marrow–derived DCs compared with cultures of DCs derived from both nontransgenic and B7-transgenic rats (Figures 5B and C). This cell death could be prevented when the Flt-3L–supplemented cultures were also supplemented with a potent, broad-spectrum caspase and apoptosis inhibitor, Q-VD (35). Q-VD restored the proportion of live cells in the B27-transgenic rat bone marrow–derived DC cultures (Figure 5D) to that observed in the cultures of DCs from nontransgenic rats (Figures 5B and C). This effect was reproducible, dose dependent, and statistically significant (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Effects of HLA–B27 expression on cultured bone marrow–derived DCs. Bone marrow cells from nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats were cultured for 7 days and analyzed by flow cytometry. A, Flt-3 ligand-supplemented cultures of DCs from B27-transgenic rats contained a higher proportion of small granular cells, as shown by the forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) characteristics of the cells. B and C, The proportion of live (annexin V–negative/DAPI-negative) cells in cultures of B27-transgenic rat bone marrow–derived DCs was significantly lower than that in cultures of DCs derived from both nontransgenic and B7-transgenic rats. D and E, Treatment with Q-VD-OPh (Q-VD) restored the proportion of live cells in the B27-transgenic rat bone marrow–derived DC cultures (D), but the effect of HLA–B27 on bone marrow–derived DCs was not observed when bone marrow–derived DCs were treated with with granulocyte-macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (E). Values in or adjacent to the quadrants in the dot plots represent the percentage of cells therein. Bars in C show the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. * = P < 0.05; *** = P < 0.001, by two-way analysis of variance. See Figure 3 for other definitions.

The effect of HLA–B27 on bone marrow–derived DCs was not observed when bone marrow–derived DCs were cultured with GM-CSF, which is another commonly used growth factor (36). Furthermore, the addition of GM-CSF to Flt-3L–supplemented bone marrow–derived DC cultures rescued the B27-transgenic DCs, restoring the normal DC phenotype (Figures 5C and E).

Induction of IL-17 production from naive CD4+ T cells by B27-transgenic Flt-3L–supplemented bone marrow–derived DCs

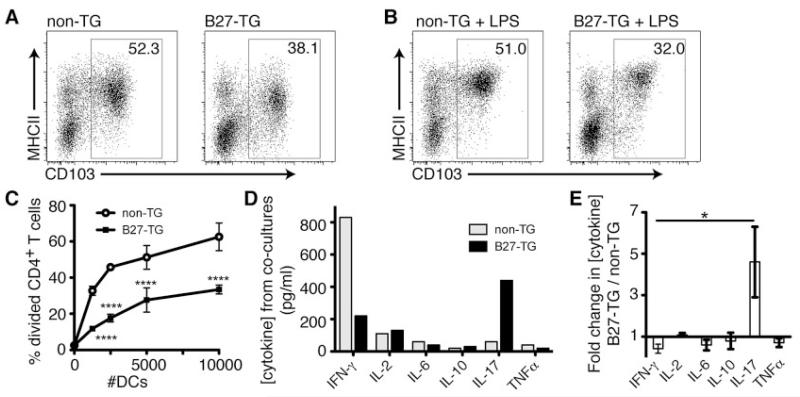

Flt-3L–supplemented bone marrow–derived DC cultures contain CD103+ class II MHC–positive cells, which are phenotypically analogous to the migratory cells in MLNs and lymph. Compared with cultures of bone marrow–derived DCs from nontransgenic control rats, cultures of bone marrow–derived DCs from B27-transgenic rats contained a smaller proportion of live (annexin V–negative/DAPI-negative) CD103+ class II MHC–positive cells (Figure 6A). When lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was added to the bone marrow–derived DC cultures overnight, all of the live CD103+ cells increased their expression of class II MHC (Figures 6A and B), which is a feature of DCs. When flow-sorted live CD103+ cells without LPS treatment were tested for their ability to stimulate allogeneic proliferation from flow-sorted naive CD4+ T cells, both nontransgenic and B27-transgenic DCs displayed this hallmark DC function (Figure 6C), although the nontransgenic DCs stimulated significantly stronger proliferation on every occasion. To investigate the ability of the DCs to induce T cell polarization, we measured the concentration of cytokines in coculture supernatants, using a Luminex assay. Nontransgenic and B27-transgenic DCs induced similar concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα (Figures 6D and E). Interestingly, nontransgenic DCs consistently induced more IFNγ, and B27-transgenic DCs induced more IL-17 production (Figures 6D and E).

Figure 6.

Functions of bone marrow–derived DCs in B27-transgenic rats. Bone marrow cells from nontransgenic and B27-transgenic rats were cultured with Flt-3 ligand (Flt-3L) for 7 days and analyzed by flow cytometry. A, Cultures of bone marrow–derived DCs from B27-transgenic rats contained a smaller proportion of live (annexin V–negative/DAPI-negative) CD103+ class II MHC–positive cells. B, The addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to the cultures for the final 12 hours before analysis resulted in increased expression of class II MHC. Values in the dot plots represent the percentage of CD103+ cells. C, Flt-3L–supplemented bone marrow–derived DCs from B27-transgenic rats were significantly less efficient at stimulating proliferation from naive CD4+ T cells compared with nontransgenic bone marrow–derived DCs. **** = P < 0.0001 versus nontransgenic, by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results are representative of 4 experiments. D and E, The concentration of cytokines in coculture supernatants was measured. Nontransgenic and B27-transgenic DCs induced similar concentrations of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), while nontransgenic DCs induced higher concentrations of interferon-γ (IFNγ), and B27-transgenic DCs induced higher concentrations of IL-17. Values in C–E are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. * = P < 0.05 by ANOVA. See Figure 3 for other definitions.

These data showed that B27-transgenic rats have a systemic defect in their ability to generate DCs, affecting bone marrow, lymph DCs, and DCs in MLNs. The results also demonstrated that the remaining DCs stimulate proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells and polarize these T cells to produce IL-17.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies using B27-transgenic rats (2) to investigate the pathogenesis of SpA have demonstrated roles for both CD4+ T lymphocytes (10, 37) and DCs (11, 12, 33). However, the mechanism by which DCs influence the development of inflammation is unclear. DCs are antigen-presenting cells that migrate via lymph from tissue to local LNs. They are uniquely potent in initiating the activation and differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells (4). Because inflammation in B27-transgenic rats and in patients with SpA often affects the intestine (2, 15, 38), we hypothesized that DCs migrating from this tissue may play a central pathogenic role.

TDC (18) is the best method for obtaining migrating intestinal DCs. Initial investigations in B27-transgenic rats on a F344 background revealed their unsuitability for TDC. In these rats, the thoracic duct is overlaid with numerous fine blood vessels that are unavoidably damaged during surgery, thereby contaminating lymph with blood-derived cells. Similar observations have been made in rats of the Lewis strain and in some strains of mice, which are not suitable for TDC (39). We therefore crossed B27-transgenic rats on a F344 background to PVG strain rats, which are suitable for cannulation (18). After crossing to PVG, as expected (3), transgene-expressing rats exhibited symptoms of inflammatory disease, including paw inflammation, nail deformities, and hair loss (Figure 1).

B27-transgenic PVG rats also displayed intestinal inflammation, and mild diarrhea was observed in all rats older than age 10 weeks. To investigate intestinal pathology, samples of duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The results demonstrated the presence of intestinal inflammation in B27-transgenic PVG rats but not in nontransgenic controls. This inflammation resembles that described for B27-transgenic rats on a LEW background (2). PVG rats were therefore used for all subsequent experiments.

Thoracic duct lymph from B27-transgenic, B7-transgenic, and nontransgenic rats contains CD103+ class II MHC–positive cells comprising ~0.4% of total lymph cells. These CD103+ class II MHC–positive lymph DCs potently stimulate proliferation from naive allogeneic CD4+ T lymphocytes (5). When we compared the frequencies and proportions of lymph DCs between B27-transgenic and nontransgenic rats, we observed that significantly fewer lymph DCs were collected from the B27-transgenic rats during the first 24-hour period. This observation was the first indication that there could be a defect in the lymph DCs from the B27-transgenic rats, although a statistically significant difference between the numbers of DCs collected from B27-transgenic and nontransgenic rats was not observed during the 24–48-hour collection period. It is possible that a difference in the numbers of migrating DCs during this period was masked by an increase in variability in the numbers of cells collected during the second day, when the flow of lymph became less consistent due to removal of the intravenous catheter that supplies the rats with saline for the first 24 hours after surgery.

Analysis of the activation status of lymph DCs from B27-transgenic and nontransgenic rats revealed no significant differences in their overall expression of the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. However, a small but significant increase in the proportion of B27-transgenic lymph DCs expressing CD25 was observed during the first 24 hours after cannulation. The increase in expression did not appear to be caused by loss of a CD25− DC population. CD25 is one of the most sensitive markers for activation of rat lymph DCs, and the data indicate a slight increase in the activation state of a proportion of the DCs migrating from the intestine of B27-transgenic rats. However, the B27-transgenic DCs did not consistently stimulate stronger proliferative responses from allogeneic CD4+ T cells.

Three functionally distinct subsets of DCs are found in the afferent lymph of wild-type PVG strain rats (24, 27). Therefore, we investigated the composition of the lymph DC subsets in the intestinal lymph of B27-transgenic rats. The 3 subsets are identified as CD172ahighCD11blow (CD172ahigh), CD172intermediate CD11b+ (CD172aintermediate), and CD172alow CD11bintermediate (CD172alow) (24). The CD172ahigh and CD172aintermediate lymph DCs are the most effective at stimulating proliferation and cytokine production from naive CD4+ T cells (24, 27). CD172alow lymph DCs are the only subset that carries fragments of apoptotic enterocytes to MLNs and can induce IL-10 production from naive CD4+ T cells (26, 27). In the B27-transgenic rats, the number and proportion of lymph DCs in the CD172alow DC population were significantly depleted compared with both the B7-transgenic and the nontransgenic controls. Although the proportions of the CD172ahigh and CD172aintermediate lymph DC populations increased, the absolute number of cells in these populations was unchanged, indicating that the CD172alow lymph DC population had disappeared and had not converted to either of the other lymph DC subsets. Indeed, the CD172alow and CD172ahigh/intermediate populations of lymph DCs have previously been shown not to be precursors of each other (23).

Analysis of MLNs produced an analogous observation: the proportion of class II MHC-positive CD103+ CD172alow MLN DCs was also reduced in B27-transgenic rats compared with both B7-transgenic and nontransgenic rats. These data demonstrate an HLA–B27–associated loss of CD103+ DCs from the lymph and MLNs of B27-transgenic rats. This defect is also apparent in the MLNs of rats at 6 weeks of age, before the onset of inflammatory disease. Importantly, the DCs in the B27-transgenic rats express high levels of the HLA–B27 molecule on their surface. The selective loss of a specific subset of migratory DCs is unprecedented in our experience. In other models of inflammation, lymph DC subsets have always been observed to maintain similar relative frequencies (24, 30).

In mice and humans, DCs are often identified by their expression of CD11c. Unfortunately, the intensity of CD11c staining with the available rat-specific antibodies is insufficient to use this marker to reliably identify DCs from tissue. Therefore, it has not been possible to ascertain whether there is a subset-specific loss of DCs purified from the intestines of B27-transgenic rats. Similarly, we have been unable to determine whether the CD172alow migratory DC subset is missing from other peripheral LNs, where CD103 expression cannot be used to identify migrating DC populations. Therefore, to determine whether the DC defect also occurred in other tissue, we cultured DCs from the bone marrow precursors of B27-transgenic, B7-transgenic, and nontransgenic rats.

Recently, the hematopoietic growth factor Flt-3L, rather than GM-CSF (36), has begun to be used to expand mouse bone marrow–derived DCs, generating DCs that more closely resemble the migratory DC populations in the steady state (34). We observed defects in Flt-3L–cultured cells from B27-transgenic rats but not in GM-CSF–cultured DC populations. Indeed, addition of GM-CSF to the Flt-3L–supplemented cultures restored normal B27-transgenic DC differentiation. When compared with B7-transgenic or nontransgenic cells, Flt-3L-supplemented B27-transgenic bone marrow–derived DC cultures contained a low frequency of CD103+ class II MHC–positive DCs and a high proportion of dead (DAPI-stained) and apoptotic (annexin V–positive) cells. The addition of the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor Q-VD prevented the proapoptotic effect of HLA–B27 in a dose-dependent manner.

Flt-3L–supplemented bone marrow–derived DCs (CD103+ class II MHC–positive) from B27-transgenic rats were significantly less efficient at stimulating proliferation from naive CD4+ T cells compared with nontransgenic bone marrow–derived DCs. However, the B27-transgenic bone marrow–derived DCs were able to stimulate some proliferation from naive CD4+ T cells. To determine the ability of bone marrow–derived DCs to induce differentiation of responding T cells, we analyzed the concentration of cytokines in supernatants from the cocultures. The cytokines induced at the highest concentrations were IL-17 and IFNγ. In every experiment, nontransgenic bone marrow–derived DCs induced more IFNγ, while B27-transgenic bone marrow-derived DCs induced higher concentrations of IL-17. Therefore, the surviving B27-transgenic DCs stimulate less proliferation from responding CD4+ T cells but polarize them to produce IL-17. These data are consistent with previous observations in B27-transgenic rats of increased production of IL-17 by CD4+ T cells (12, 40) and in human SpA (for review, see ref. 41).

Our data show that a systemic defect in DC generation occurs in B27-transgenic rats, affecting Flt-3L–dependent DCs in vitro and the CD172alow subset of migratory DCs in vivo. In rodents, lymph DCs are Flt-3L dependent (30, 42, 43). We therefore consider it likely that the losses of CD172alow DCs in vivo and of Flt-3L–dependent DCs in vitro are closely related phenomena. However, rat bone marrow–derived DCs do not differentiate into CD172a+ and CD172a− subsets, so it was not possible to directly test this correlation.

The mechanism by which HLA–B27 expression drives the apoptotic death of specific DCs is not clear. Consistent with the results reported here, we previously observed that the CD172a− (CD4−) subset of splenic DCs die more quickly when cultured (33). Therefore, the unfolded protein response (UPR), a coordinated cellular program that acts to reduce the level of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum and is known to be induced by expression of HLA–B27 in B27-transgenic rats (33, 44, 45), may accelerate apoptotic death in this already-susceptible DC subset. Apoptosis is known to be the consequence of persistent activation of the UPR (for review, see ref. 46). We have been unable, however, to identify apoptotic DCs in the lymph, MLNs, or intestines of B27-transgenic rats and are therefore unable to unequivocally identify the mechanism driving the loss of this DC subset in vivo.

We describe defects in migratory DC populations in B27-transgenic rats that are involved in the maintenance of self-tolerance to intestinal antigens (6, 26). A loss of self-tolerance caused by this DC defect, combined with the enhanced capacity of the remaining DCs to stimulate IL-17 production from T cells, could contribute to the establishment of inflammation in B27-transgenic rats. These changes in DC functions would allow development of the endoplasmic reticulum stress–induced HLA–B27–dependent IL-23/Th17 response described by other investigators (12, 40, 47). Identification of this in vivo defect in DCs, and our in vitro data demonstrating its reversibility, indicate potential for the development of novel therapeutic manipulations of the immune system to treat SpA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Prof. Allan Mowat for his help and advice and to the staff of the University of Glasgow Flow Cytometry Core Facility.

Supported by a Capacity Building Award in Integrative Mammalian Biology funded by a public-private partnership of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the British Pharmacological Society Integrative Pharmacology Fund (donors: AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer), the Health Technologies Knowledge Transfer Network, the Medical Research Council, and the Scottish Further and Higher Education Funding Council (to Ms Utriainen) and by grants from Arthritis Research UK (to Dr. Firmin), The Nuffield Foundation (to Ms Wright), and the Medical Research Council (to Dr. Cerovic).

REFERENCES

- 1.Brewerton DA, Hart FD, Nicholls A, Caffrey M, James DC, Sturrock RD. Ankylosing spondylitis and HL-A 27. Lancet. 1973;1:904–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer RE, Maika SD, Richardson JA, Tang JP, Taurog JD. Spontaneous inflammatory disease in transgenic rats expressing HLA-B27 and human β2m: an animal model of HLA-B27-associated human disorders. Cell. 1990;63:1099–112. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90512-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taurog JD, Hammer RE. Experimental spondyloarthropathy in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. Clinical Rheumatol. 1996;15(Suppl 1):22–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03342640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu LM, MacPherson GG. Lymph-borne (veiled) dendritic cells can acquire and present intestinally administered antigens. Immunology. 1991;73:281–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worbs T, Bode U, Yan S, Hoffmann MW, Hintzen G, Bernhardt G, et al. Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:519–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β- and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahlen-Yrlid L, Gustafsson T, Westlund J, Holmberg A, Strombeck A, Blomquist M, et al. CD11chigh dendritic cells are essential for activation of CD4+ T cells and generation of specific antibodies following mucosal immunization. J Immunol. 2009;183:5032–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breban M, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Taurog JD. Transfer of the inflammatory disease of HLA-B27 transgenic rats by bone marrow engraftment. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1607–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breban M, Fernandez-Sueiro JL, Richardson JA, Hadavand RR, Maika SD, Hammer RE, et al. T cells, but not thymic exposure to HLA-B27, are required for the inflammatory disease of HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Immunol. 1996;156:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacquard-Bouder C, Chimenti MS, Giquel B, Donnadieu E, Fert I, Schmitt A, et al. Alteration of antigen-independent immunologic synapse formation between dendritic cells from HLA–B27–transgenic rats and CD4+ T cells: selective impairment of costimulatory molecule engagement by mature HLA–B27. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1478–89. doi: 10.1002/art.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glatigny S, Fert I, Blaton MA, Lories RJ, Araujo LM, Chiocchia G, et al. Proinflammatory Th 17 cells are expanded and induced by dendritic cells in spondylarthritis-prone HLA–B27–transgenic rats. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:110–20. doi: 10.1002/art.33321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, Craddock N, Deloukas P, Duncanson A, et al. Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1329–37. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans DM, Spencer CC, Pointon JJ, Su Z, Harvey D, Kochan G, et al. Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease susceptibility. Nature Genet. 2011;43:761–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taurog JD, Richardson JA, Croft JT, Simmons WA, Zhou M, Fernandez-Sueiro JL, et al. The germfree state prevents development of gut and joint inflammatory disease in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2359–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieleman LA, Goerres MS, Arends A, Sprengers D, Torrice C, Hoentjen F, et al. Lactobacillus GG prevents recurrence of colitis in HLA-B27 transgenic rats after antibiotic treatment. Gut. 2003;52:370–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.3.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mielants H, Veys EM, Cuvelier C, De Vos M, Goemaere S, De Clercq L, et al. The evolution of spondyloarthropathies in relation to gut histology. III. Relation between gut and joint. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pugh CW, MacPherson GG, Steer HW. Characterization of nonlymphoid cells derived from rat peripheral lymph. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1758–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.6.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milling S, Yrlid U, Cerovic V, MacPherson G. Subsets of migrating intestinal dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:259–67. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaensson E, Uronen-Hansson H, Pabst O, Eksteen B, Tian J, Coombes JL, et al. Small intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells display unique functional properties that are conserved between mice and humans. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2139–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milling SW, Jenkins C, MacPherson G. Collection of lymph-borne dendritic cells in the rat. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milling S, MacPherson G. Isolation of rat intestinal lymph DC. In: Naik SH, editor. Dendritic cell protocols. Humana Press; Totawa (NJ): 2009. pp. 281–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Zhang M, Jenkins C, MacPherson GG. Dendritic cell heterogeneity in vivo: two functionally different dendritic cell populations in rat intestinal lymph can be distinguished by CD4 expression. J Immunol. 1998;161:1146–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yrlid U, Cerovic V, Milling S, Jenkins CD, Klavinskis LS, MacPherson GG. A distinct subset of intestinal dendritic cells responds selectively to oral TLR7/8 stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2639–48. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taurog JD, Maika SD, Simmons WA, Breban M, Hammer RE. Susceptibility to inflammatory disease in HLA-B27 transgenic rat lines correlates with the level of B27 expression. J Immunol. 1993;150:4168–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang FP, Platt N, Wykes M, Major JR, Powell TJ, Jenkins CD, et al. A discrete subpopulation of dendritic cells transports apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells to T cell areas of mesenteric lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2000;191:435–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milling S, Jenkins C, Yrlid U, Cerovic V, Edmond H, McDonald V, et al. Steady state migrating intestinal dendritic cells induce potent inflammatory responses in naïve CD4 T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:156–65. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:782–7. doi: 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Fontecha A, Sebastiani S, Hopken UE, Uguccioni M, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. J Exp Med. 2003;198:615–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turnbull E, Yrlid U, Jenkins CD, MacPherson G. Intestinal dendritic cell subsets: differential effects of systemic TLR4 stimulation on migratory fate and activation in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:1374–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacPherson GG, Fossum S, Harrison B. Properties of lymphborne (veiled) dendritic cells in culture. II. Expression of the IL-2 receptor: role of GM-CSF. Immunology. 1989;68:108–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Pabst O, Palmqvist C, Marquez G, Forster R, et al. Functional specialization of gut CD103+ dendritic cells in the regulation of tissue-selective T cell homing. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1063–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhaenens M, Fert I, Glatigny S, Haerinck S, Poulain C, Donnadieu E, et al. Dendritic cells from spondylarthritis-prone HLA–B27–transgenic rats display altered cytoskeletal dynamics, class II major histocompatibility complex expression, and viability. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2622–32. doi: 10.1002/art.24780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naik SH, Proietto AI, Wilson NS, Dakic A, Schnorrer P, Fuchsberger M, et al. Generation of splenic CD8+ and CD8− dendritic cell equivalents in Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand bone marrow cultures. J Immunol. 2005;174:6592–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caserta TM, Smith AN, Gultice AD, Reedy MA, Brown TL. Q-VD-OPh, a broad spectrum caspase inhibitor with potent antiapoptotic properties. Apoptosis. 2003;8:345–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1024116916932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.May E, Dorris ML, Satumtira N, Iqbal I, Rehman MI, Lightfoot E, et al. CD8+ T cells are not essential to the pathogenesis of arthritis or colitis in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Immunol. 2003;170:1099–105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elewaut D, Matucci-Cerinic M. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and extra-articular manifestations in everyday rheumatology practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1029–35. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ionac M, Laskay T, Labahn D, Geisslinger G, Solbach W. Improved technique for cannulation of the murine thoracic duct: a valuable tool for the dissection of immune responses. J Immunol Methods. 1997;202:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeLay ML, Turner MJ, Klenk EI, Smith JA, Sowders DP, Colbert RA. HLA–B27 misfolding and the unfolded protein response augment interleukin-23 production and are associated with Th17 activation in transgenic rats. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2633–43. doi: 10.1002/art.24763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Layh-Schmitt G, Colbert RA. The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis in spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:392–7. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328303204b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edelson BT, Wumesh KC, Juang R, Kohyama M, Benoit LA, Klekotka PA, et al. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8+ conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:823–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, Roux ER, Lyman SD, Shortman K, et al. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1953–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner MJ, Sowders DP, DeLay ML, Mohapatra R, Bai S, Smith JA, et al. HLA-B27 misfolding in transgenic rats is associated with activation of the unfolded protein response. J Immunol. 2005;175:2438–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner MJ, Delay ML, Bai S, Klenk E, Colbert RA. HLA-B27 up-regulation causes accumulation of misfolded heavy chains and correlates with the magnitude of the unfolded protein response in transgenic rats: implications for the pathogenesis of spondylarthritis-like disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:215–23. doi: 10.1002/art.22295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. 2008;454:455–62. doi: 10.1038/nature07203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodall JC, Wu C, Zhang Y, McNeill L, Ellis L, Saudek V, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced transcription factor, CHOP, is crucial for dendritic cell IL-23 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011736107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]