Abstract

Ca2+ channels and calmodulin are two prominent signaling hubs1 that synergistically impact functions as diverse as cardiac excitability2, synaptic plasticity3, and gene transcription4. It is thereby fitting that these hubs are in some sense coordinated, as the opening of CaV1-2 Ca2+ channels are regulated by a single calmodulin (CaM) constitutively complexed with channels5. The Ca2+-free form of CaM (apoCaM) is already preassociated with the IQ domain on the channel carboxy terminus, and subsequent Ca2+ binding to this ‘resident’ CaM drives conformational changes that then trigger regulation of channel opening6. Another potential avenue for channel-CaM coordination could arise from the absence of Ca2+ regulation in channels lacking a preassociated CaM6,7. Natural fluctuations in CaM levels might then influence the fraction of regulatable channels, and thereby the overall strength of Ca2+ feedback. However, the prevailing view has been that the ultra-strong affinity of channels for apoCaM ensures their saturation with CaM8, yielding a significant form of concentration independence between Ca2+ channels and CaM. Here, we reveal significant exceptions to this autonomy, by combining electrophysiology to characterize channel regulation, with optical FRET sensor determination of free apoCaM concentration in live cells9. This approach translates quantitative CaM biochemistry from the traditional test-tube context, into the realm of functioning holochannels within intact cells. From this perspective, we find that long splice forms of CaV1.3 and CaV1.4 channels include a distal carboxy tail10-12 that resembles an enzyme competitive inhibitor, which retunes channel affinity for apoCaM so that natural CaM variations affect the strength of Ca2+ feedback modulation. Given the ubiquity of these channels13,14, the connection between ambient CaM levels and Ca2+ entry via channels is broadly significant for Ca2+ homeostasis. Strategies like ours promise key advances for the in situ analysis of signaling molecules resistant to in vitro reconstitution, such as Ca2+ channels.

Our investigations build on a CaV1.4 channel mutation underlying congenital stationary night blindness15. This mutation yields a premature stop that deletes the distal carboxy tail (DCT) of these retinal Ca2+ channels, and produces a surprising emergence of their Ca2+ regulation by CaM11,12 (Ca2+-dependent inactivation, CDI). Full-length CaV1.4 channels lack CDI11,12, thereby maintaining Ca2+-driven transmitter release at tonically depolarized retinal synapses. Hence, the emergence of CDI likely impairs vision. Mechanistically, the DCT contains an ICDI module that is reported to somehow ‘switch off’ the latent CDI of CaV1.4 channels11,12.

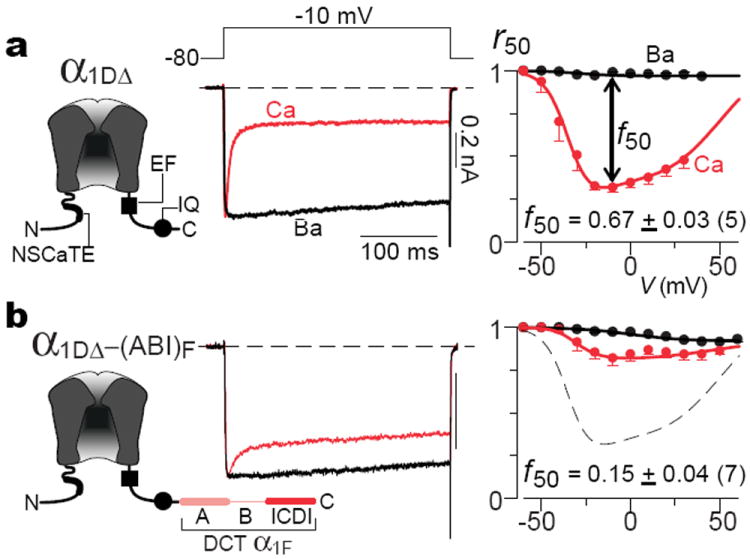

Figure 1 summarizes our initial characterization of ICDI effects. Because CaV1.4 channels yield diminutive currents16, we appended the DCT of the main CaV1.4 subunit (α1F) onto the core of better-expressing CaV1.3 channels (main subunit α1D). This previous approach permits robust investigation of DCT effects11,12. As baseline, Fig. 1a displays the CDI of core CaV1.3 channels (left, α1DΔ), similar to natural short splice variants8. Core channels contain all elements required for CDI6,17, including the IQ domain for apoCaM preassociation6, and EF-hand-like region for CDI transduction18. Depolarization thereby evoked rapidly decaying Ca2+ current (middle, red trace), indicative of strong CDI. Since Ba2+ binds CaM poorly17, the slow Ba2+ current decay (black trace) delineates the background inactivation of a distinct voltage-dependent process6,7 (VDI). Thus, the fraction of peak current remaining after 50-msec depolarization (right, r50) relates intimately to inactivation, with the difference between Ca2+ and Ba2+ r50 relations indexing CDI (f50). Appending the CaV1.4 DCT onto the CaV1.3 core (Fig. 1b, left) strikingly reduced CDI (middle and right) versus control (dashes) (Supplemental 1.2). Importantly, the DCT did not altogether abolish CDI as reported before11,12, but spared a clear residuum. This difference foreshadowed major mechanistic and biological consequences.

Figure 1. Distal carboxy tail of CaV1.4 weakens Ca2+ regulation of channels.

a, Core CaV1.3 channel contains all known structural elements required for CDI (left schematic of main subunit α1DΔ, containing NSCaTE17, EF18, and IQ6) and thereby exhibits robust CDI (right two sub-panels). Average f50 CDI metric at bottom (mean ± sem), with number of cells in parentheses. Throughout, current bars pertain to Ca2+ currents, Ba2+ currents scaled for kinetic comparison, and tail currents clipped to frame. b, Adding DCT of α1F (main pore-forming CaV1.4 subunit) to core CaV1.3 channel weakens CDI. A, B, and ICDI segments of DCT defined in Supplemental 1.1. Dashed curve reproduces baseline from a.

Hints of these consequences came by qualitative consideration of underlying mechanism. As background, we recapitulated coarse structural underpinnings of DCT effects. To confirm DCT collaboration with core channel elements11,12, we showed the lack of DCT effects on CaV2.2 channels (Supplemental 1.3), which presumably lack complementing modules. As well10,12, only ICDI and A sub-segments (Fig. 1b, left) are required (Supplemental 1.4). Beyond these initial points of clarity, actual DCT mechanisms remain controversial. One group used GST pulldowns of channel peptides to support an allosteric mechanism (Supplemental 1.5), where the ICDI associates with an EF-hand-like module to eliminate CDI transduction12 (Fig. 1a, left), but leaves apoCaM/channel binding unchanged. By contrast, another group employed channel peptide FRET to advance a competitive mechanism (Supplemental 1.5), where ICDI competes with apoCaM for binding near the channel IQ domain (Fig. 1a, left), thus inhibiting CDI by displacing CaM from channels11.

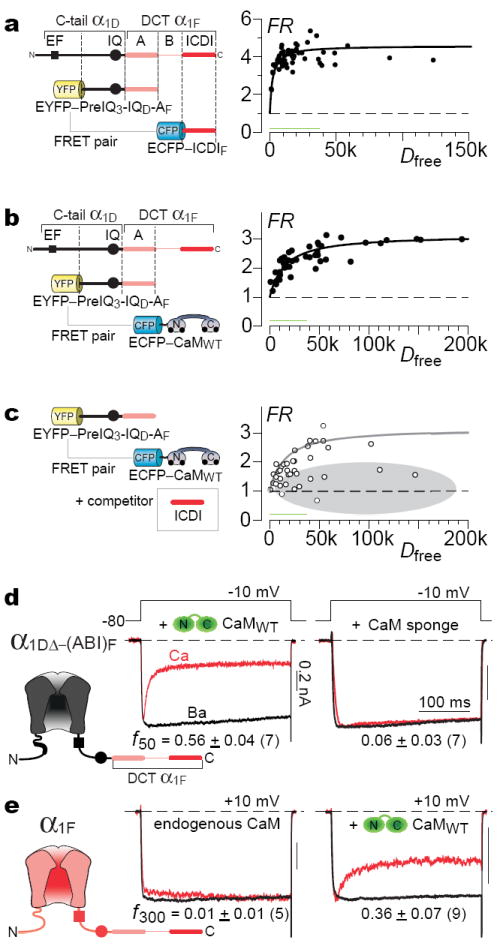

To aid resolution, we pursued two preliminary approaches. First, live-cell FRET 2-hybrid assays6,17 tested whether the CaV1.4 ICDI (Fig. 2a, CFP fused to ICDI, ECFP–ICDIF) could bind the presumed apoCaM preassociation module of CaV1.3 (YFP fused to PreIQ3–IQ–A from Fig. 1b, EYFP–PreIQ3–IQD–AF; Supplemental 2.1). We thus resolved a high-affinity in situ binding curve (Fig. 2a), where FRET strength (FR) is plotted cell-by-cell versus free ECFP–ICDIF concentration (Dfree, free donor). By contrast to prior analyses utilizing single-number FRET indices11, our binding-curve clearly excludes low-affinity interaction, and a similar binding curve held true for partners solely derived from CaV1.4 (Supplemental 2.2). We also confirmed avid binding between apoCaM (ECFP–CaMWT in resting cells) and this EYFP–PreIQ3–IQD–AF module6 (Fig. 2b). More telling, the ICDI (without fluorophore) attenuated the same apoCaM interaction (Fig. 2c, gray zone), suggesting that ICDI and apoCaM could vye for IQ occupancy (Supplemental Fig. 2.2b). In all, these data confirmed the potential for competition, but pertained only to peptides, without guarantee of analogous events within intact channels.

Figure 2. Provisional evidence for competition.

a, FRET, CFP-tagged ICDI of α1F versus YFP-tagged PreIQ3-IQ-A from Fig. 1b (Supplemental 2.1). FR ∝ FRET efficiency times fraction of YFP-tagged molecules bound6. Dfree, relative concentration of unbound CFP-tagged molecules; green bar ~500 nM6. b, FRET, apoCaM versus PreIQ3-IQ-A in a. c, ICDI (without fluorophore) attenuates binding in b. Gray reference curve from b. d, Left, CDI is rescued upon overexpressing CaM with chimera in Fig. 1b. Right, CaM sponge (CaV1.2 YFP–PreIQ3-IQ6) eliminates CDI. e, Overexpressing CaM with full-length CaV1.4. f300, 300-ms version of f50.

Accordingly, a second provisional approach specifically targeted the holochannel configuration. Scrutiny of mechanisms (Supplemental 1.5) revealed that manipulating apoCaM levels would affect CDI only in the competitive, but not strict allosteric framework. Indeed, elevating CaM sharply reversed ICDI effects (Fig. 2d, middle), and apoCaM chelation eliminated residual CDI (Fig. 2d, right; Supplemental 2.3). Importantly, augmenting CaM also boosted CDI of full-length CaV1.4 channels (Fig. 2e, cf., ref. 19). Overall, both preliminary approaches supported competition, and the residual CDI seen earlier (Fig. 1b) appeared to reflect incomplete competition. Still, these data neither excluded more nuanced allosteric mechanisms20, nor revealed whether biologically relevant CaM fluctuations could modulate CDI.

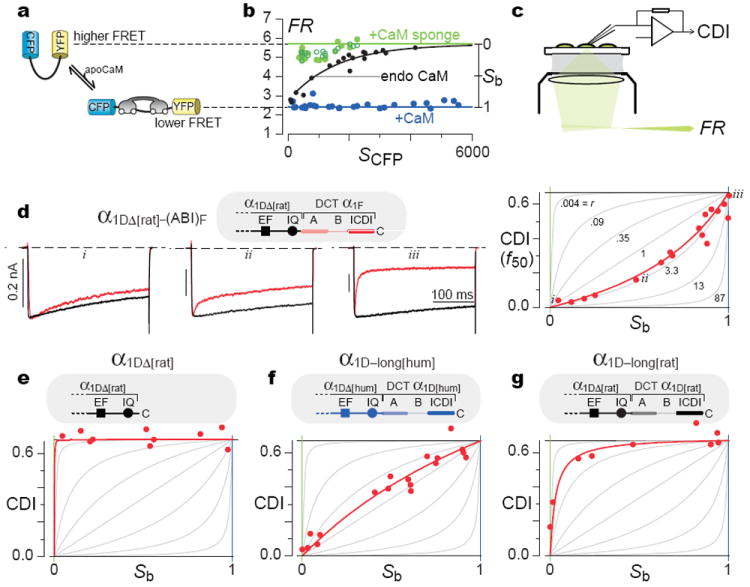

These limitations might be overcome, if only the free apoCaM concentration could be quantified within the very cells where CDI was measured. If so, one could delineate the holochannel equivalent of classic enzyme inhibition plots20, which rigorously distinguish among mechanisms. Accordingly, we incorporated a recently developed optical FRET-based sensor of apoCaM, BSCaMIQ. Here, CFP and YFP flank the apoCaM binding site of neuromodulin9 (Fig. 3a), such that the overall FRET is determined by free apoCaM concentration. We confirmed the limiting behaviors by coexpressing BSCaMIQ with excess CaM (Fig. 3b, blue line at FRmin) or CaM-chelating peptides (green line at FRmax; Supplemental 3.1). As expected, FR was nearly independent of isolated CFP fluorescence (SCFP), an approximate measure of sensor expression in each cell. By contrast, when BSCaMIQ was expressed alone, FR demonstrated a comforting rise towards FRmax (Fig. 3b, black line), as anticipated for a sensor that itself chelates and decreases free apoCaM. With reassurance of BSCaMIQ performance in our system, we coexpressed BSCaMIQ and Ca2+ channels, and measured free apoCaM concentration before determining CDI in the same cell (Fig. 3c). If free apoCaM were varied among cells by CaM overexpression or chelation, the resulting CDI versus apoCaM plot would rigorously distinguish among mechanisms. Specifically, using the relation between FRET and free apoCaM concentration in our cells9 (Supplemental 3.2), the exact signature of competition20 becomes as shown in Fig. 3d (right, gray curves) and

| (1) |

where CDImax is the maximal CDI without ICDI; Kd-channel-apparent is the apparent dissociation constant of channels for apoCaM (with competitive inhibitor); Kd-sensor is the dissociation constant of BSCaMIQ for apoCaM9 (2.3 μM); and Sb is the fraction of sensor bound to apoCaM (Supplemental 3.3). As Fig. 3b shows, Sb is directly determined from FR, and ranges from 0 to 1 with increasing apoCaM. If ICDI competition is strong (r > 1), curves will be upwardly concave (Fig. 3d, right, gray curves); if weak (r < 1), curves will be downwardly concave.

Figure 3. Live-cell holochannel biochemistry proves competition.

a, BSCaMIQ schematic. b, BSCaMIQ expressed alone (black curve and data), and coexpressed with CaM or CaM sponges (neuromodulin IQ (filled green, Supplemental 3.1) or CaV1.2 PreIQ3-IQ6 (open green)). SCFP, isolated CFP fluorescence6. c, Approach to obtain CDI and FRET readouts of apoCaM (FR) in single cells. d, CDI–Sb analysis for α1DΔ[rat]–(ABI)F, respectively, for -10 mV steps. Right, family of gray CDI–Sb curves illustrate potential profiles for competitive inhibition, according to Eq. 1. Superimposed red data and fit conform to competitive profile. Left, corresponding exemplar traces, labelled i-iii. e-g, CDI–Sb analysis for α1DΔ[rat], α1D–long[hum], and α1D–long[rat]. Format as in d.

Figure 3d also displays the experimental outcome for core CaV1.3 channels affixed to the CaV1.4 DCT (α1DΔ–(ABI)F, from Fig. 1b). In the CDI–Sb plot on the right, each symbol corresponds to a single cell, and together these data fit remarkably well to the competitive scheme (red curve, Eq. 1). On the left, current traces from exemplar cells (i, ii, and iii) explicitly demonstrate the appropriate increase of CDI with growing Sb and apoCaM. Importantly, parallel analysis of core CaV1.3 channels revealed far greater apoCaM affinity (Fig. 3e), yielding maximal CDI throughout. Hence, the upward concavity in Fig. 3d is a genuine ICDI effect, not an unanticipated property of the CaV1.3 core. Critically, at high apoCaM (Sb ~ 1), CDI of both constructs converged, yielding a hallmark of competition20.

Buoyed by advances for the retinal CaV1.4 DCT, we wondered whether CDI–Sb analysis might uncover like DCT mechanisms in other Ca2+ channel subtypes, with yet broader distribution and impact. We considered a long splice variant of the human CaV1.3 channel10 (α1D–long[hum]), which contains a DCT homologous to that in CaV1.4. This long variant has recently been reported to exhibit decreased CDI10 compared to a short variant akin to core channels (e.g., Fig. 3e). It thus seemed plausible that a competitive ICDI mechanism could extend to these channels, an important possibility given the wide distribution of CaV1.3 channels13,14, and the predominance of the long variant throughout brain10. Complicating this view, however, were our prior observations that corresponding long and short variants of rat CaV1.3 channels exhibit no difference in CDI8. Indeed, all experiments to this point used the rat CaV1.3. Accordingly, we undertook CDI–Sb analysis of long CaV1.3 variants from both human and rat. The long CaV1.3 variant of human (Fig. 3f) clearly adhered to a competitive ICDI mechanism, with maximal CDI equivalent to that of core channels (cf., Fig. 3d). This argues that long forms of CaV1.3 and CaV1.4 channels do share a common ICDI mechanism. However, the CDI–Sb relation for the long CaV1.3 variant of humans differs quantitatively from that with the CaV1.4 DCT (cf., Figs. 3f, d), indicating that the strength of ICDI competition is customized by channel isoform. Indeed, the long CaV1.3 variant of rat exhibited extreme customization (Fig. 3g). Here, CDI–Sb analysis unmasks competitive inhibition, but the competition is weak enough that CDI remains maximal, except with overt chelation of apoCaM (at Sb ~ 0). The steep saturation of this CDI–Sb relation thus explains prior data that CDI was unaffected by the rat CaV1.3 DCT, as no depletion was used8. Importantly, the CDI–Sb curve for the long rat variant (Fig. 3g) is distinct from that for the CaV1.3 core (Fig. 3e), where CDI stayed maximal throughout. Hence, the rat CaV1.3 DCT entails customization, not elimination of the competitive inhibitory mechanism (Supplemental 3.4).

The similarity of DCT elements, particularly of human and rat CaV1.3, suggested that minute differences produce extremes of tuning. Indeed, we found that a single valine-to-alanine switch within the ICDI explains the difference (human:rat, ICDI position 47; Supplemental 3.5).

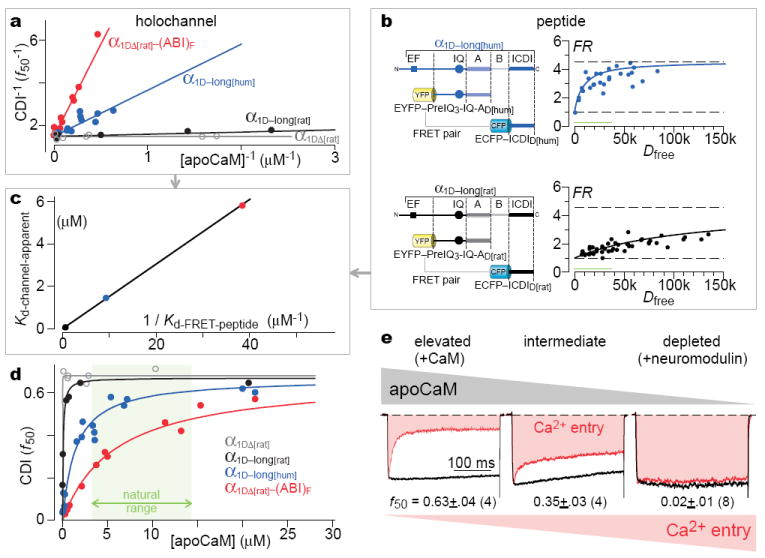

While the CDI–Sb analysis established a competitive inhibitory mechanism at the holochannel level, still critically unresolved was whether the ICDI/IQ peptide interactions studied thus far (Fig. 2c) were relevant to holochannel competition, especially given the multiplicity of CaM sites in channels6,17,21,22. This is a generic challenge for large signaling complexes. Importantly, enzyme analysis could be extended to resolve even this ambiguity. Fig. 4a summarizes our data for competitive inhibition in holochannels, recasting CDI–Sb data into classic reciprocal-plot form20, where channel CDI (f50) corresponds to enzyme catalytic velocity V, and apoCaM to enzyme substrate S. Visual accord with the textbook signature of competition underscores the insights already provided by in situ holochannel biochemistry. Beyond this, if ICDI/IQ binding actually underlies holochannel competition, enzyme analysis additionally predicts a linear relation between the apparent apoCaM dissociation constant for holochannels (Kd-channel-apparent, Eq. 1) and the reciprocal of the peptide dissociation constant (1 / Kd-FRET-peptide)

| (2) |

where Kd-channel is the holochannel dissociation constant for apoCaM without inhibitor, and [ICDI] is the effective concentration of ICDI at the channel preassociation site for apoCaM20 (Supplemental 4.1) Conversely, if peptide interactions are peripheral or the inhibitory mechanism not strictly competitive, this relation will likely fail (Supplemental 4.2). To test this prediction, we noted that CDI–Sb analysis had already determined Kd-channel-apparent for channels with three different ICDIs (Figs. 3d, f, g; Fig. 4a). Also, Kd-FRET-peptide for the CaV1.4 ICDI was measured in Fig. 2a, and the remaining Kd-FRET-peptide values are deduced in Fig. 4b. The resulting linear plot (Fig. 4c) argues that ICDI/IQ binding indeed underlies holochannel competition, and apoCaM/channel preassociation involves the IQ with Kd-channel ~10 nM (Fig. 3e, Supplemental 4.1).

Figure 4. Molecular interactions and biology of competitive inhibitory tuning.

a, Reciprocal-plot representation of Fig. 3 (d-g) relations. b, FRET assays characterizing presumed peptide interactions underlying holochannel competition (as in a). c, Linear relation between holochannel and peptide competition parameters. d, Linear format of quantitative tuning relations. Green biological range, 99% boundaries23. e, Consequences of connectivity in long variant of human CaV1.3. Natural variability of native CaM buffers (neuromodulin) affects CDI and Ca2+ entry for long variant of human CaV1.3. Left, CaM coexpression; middle, endogenous CaM; right, neuromodulin coexpression.

Transforming the reciprocal plots (Fig. 4a) into normal format raises diverse biological implications (Fig. 4d). The dogma has been that Ca2+ channels exhibit an ultra-strong apoCaM affinity8, ensuring maximal CDI over the green biological range23, as confirmed for channels lacking ICDI (Fig. 4d, gray curve). Earlier reports that ICDI simply ‘switches off’ CDI11,12 further promoted this perceived dissociation of CDI and apoCaM fluctuations. By contrast, we show here that the ICDI retunes CDI–[apoCaM] relations, so that natural variations of apoCaM modulate CDI and overall Ca2+ entry (Fig. 4d). Such interconnection opens new vistas, given the widespread impact and distribution of CaV1.3 and CaV1.4 channels13-15, and the regulation of CaM23. For example, coexpressing neuromodulin (a bio-molecule that impacts synaptic growth/remodeling/plasticity and buffers apoCaM24) with the long variant of human CaV1.3 channels indeed lowers apoCaM sufficiently to eliminate CDI and promote Ca2+ entry (Fig. 4e, Supplemental 4.3). This outcome may bear on schizophrenia, where hippocampal neuromodulin is decreased25. Moreover, neurodegenerative diseases are potentially affiliated with Ca2+ dysregulation and thereby altered apoCaM26. In Parkinson’s, excess alpha-synuclein is pathogenic27; these molecules bind apoCaM28; and elevated substantia-nigral CaV1.3 activity predisposes for disease29. In Alzheimer’s, CaM is depleted26. More broadly, certain heart failure models feature elevated CaM30. In all, exploring the (patho) physiological sequelae of Ca2+ channel connectivity with CaM now beckons at the frontier.

Methods

Molecular biology

Engineering of the rat CaV1.3 long variant (α1D, AF370009.1) were made as follows. For Fig. 1, a unique XbaI site was introduced by PCR following the IQ domain. The DCT of human α1F (NP005174) was amplified and cloned non-directionally via the unique XbaI site, yielding the sequence in Supplemental 1.1. For Fig. S3.4, a like process was repeated, except appropriate sections of the DCT of rat CaV1.3 long variant (α1D, AF370009.1) were first PCR amplified with flanking SpeI and XbaI sites (compatible ends), and cloned into the aforementioned unique XbaI site, leaving a unique XbaI site after the inserted section of the rat DCT. Appropriate segments of the ICDI segment of the human CaV1.3 long variant (α1D, NM000718) were then PCR amplified with flanking SpeI and XbaI sites, and cloned into the unique XbaI site, leaving a unique XbaI site after the inserted ICDI segment. For the V41A insertion (Fig. S3.4d), the human ICDI was point mutated via QuikChange® Mutagenesis (Strategene) prior to PCR amplification and insertion into the channel construct. For the A41V insertion (Fig. S3.4e), the rat ICDI was similar point mutated before cloning into the unique XbaI site of the aforementioned engineered rat CaV1.3 long variant. For FRET 2-hybrid constructs, fluorophore-tagged CaM constructs were made as described6. Other FRET constructs made by replacing CaM with appropriate PCR amplified segments, via unique NotI and XbaI sites flanking CaM6. Details of CaM sponges in Supplemental 3.1. All segments subject to PCR or QuikChange® were verified in their entirety by sequencing.

Transfection of HEK293 cells

For electrophysiology experiments, HEK293 cells were cultured in 10 cm plates, and channels were transiently transfected by a calcium phosphate protocol6,8. We applied 8 μg of cDNA encoding the desired channel α1 subunit, along with 8 μg of rat brain β2a (M80545) and 8 μg of rat brain α2δ (NM012919.2) subunits. β2a minimized voltage inactivation, enhancing resolution of CDI. Additional cDNA was added as required in co-transfections. All of the above cDNA constructs were driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter. To enhance expression, cDNA for simian virus 40 T antigen (1-2 μg) was co-transfected. For fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) 2-hybrid experiments, transfections and experiments were performed as described6. Electrophysiology and FRET were done at room temperature 1–2 d after transfection.

Whole-cell recording

Whole-cell recordings were obtained at room temperature using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Electrodes were pulled with borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, MTW 150-F4), resulting in 1–3 MΩ resistances, before series resistance compensation of 80%. The internal solutions contained, (in mM): CsMeSO3, 135; CsCl2, 5; MgCl2, 1; MgATP, 4; HEPES (pH 7.3), 5; and EGTA, 5; at 290 mOsm adjusted with glucose. The bath solution contained (in mM): TEA-MeSO3, 140; HEPES, 10, pH 7.3; CaCl2 or BaCl2, 10; 300 mOsm, adjusted with glucose. These are as reported8. To augment currents for the full-length CaV1.4 experiments in Fig. 2e, we used 40 mM CaCl2 or BaCl2 in the bath solution, while adjusting TEA-MeSO3 downwards to preserve osmolarity. As well, 5 μM Bay K 8644 was present in the bath throughout to further enhance currents.

FRET optical imaging

FRET 2-hybrid experiments were carried out in HEK293 cells and analyzed as described6. During imaging, the bath solution was either a Tyrode’s buffer containing 2 mM Ca2+, or the standard electrophysiological recording bath solution described above. Concentration-dependent spurious FRET was subtracted from the raw data prior to binding-curve analysis17. For simultaneous BSCaMIQ imaging and patch-clamp recording, three-cube FRET measurements were obtained prior to whole-cell break in, and did not change appreciably thereafter. For ICDI binding curves in Figs. 2a and 4b, unlabelled IQ domain of neuromodulin (sequence in Supplemental 3.1) was coexpressed to reduce interference from endogenous CaM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Tadross, Ivy Dick, and members of the Ca2+ signals lab for valuable comments; Michael Tadross for custom and elegant data-acquisition software; D.J. Black and Anthony Persechini for BSCaMIQ and neuromodulin cDNA; J. McRory and Terry Snutch for human α1F cDNA; J. Streissnig for the human α1D cDNA; and Vincent Wu for earlier foundational experiments. Supported by grants from the NIMH (to D.T.Y.), NHLBI (D.T.Y.), and NIDCD (D.T.Y. and Paul Fuchs).

Footnotes

Author contributions

X.L. devised and refined experimental design; carried out all phases of the experiments; and performed extensive data analysis. P.S.Y. consulted on initial molecular biology approaches; constructed certain channels with ICDI point mutations; and contributed importantly to CaV1.4 expression strategies and electrophysiological characterization. W.Y. conducted FRET experiments; undertook molecular biology; and extensively managed technical aspects of the project. D.T.Y. conceived, refined, and oversaw the experiments; performed FRET experiments; analyzed data; and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabasi AL. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000;407:651–654. doi: 10.1038/35036627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alseikhan BA, DeMaria CD, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu J, Wu LG. The decrease in the presynaptic calcium current is a major cause of short-term depression at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2005;46:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krey JF, Dolmetsch RE. Molecular mechanisms of autism: a possible role for Ca2+ signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang PS, Mori MX, Antony EA, Tadross MR, Yue DT. A single calmodulin imparts distinct N- and C-lobe regulatory processes to individual CaV1.3 channels. Biophys J. 2007;92:354a. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson MG, Liang H, Mori MX, Yue DT. FRET two-hybrid mapping reveals function and location of L-type Ca2+ channel CaM preassociation. Neuron. 2003;39:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang H, et al. Unified mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation across the Ca2+ channel family. Neuron. 2003;39:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang PS, et al. Switching of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CaV1.3 channels by calcium binding proteins of auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10677–10689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3236-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black DJ, Leonard J, Persechini A. Biphasic Ca2+-dependent switching in a calmodulin-IQ domain complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6987–6995. doi: 10.1021/bi052533w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A, et al. Modulation of voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating of CaV1.3 L-type calcium channels by alternative splicing of a C-terminal regulatory domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:20733–20744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802254200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh A, et al. C-terminal modulator controls Ca2+-dependent gating of CaV1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1108–1116. doi: 10.1038/nn1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahl-Schott C, et al. Switching off calcium-dependent inactivation in L-type calcium channels by an autoinhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15657–15662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604621103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platzer J, et al. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namkung Y, et al. Requirement for the L-type Ca2+ channel alpha1D subunit in postnatal pancreatic beta cell generation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1015–1022. doi: 10.1172/JCI13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strom TM, et al. An L-type calcium-channel gene mutated in incomplete X-linked congenital stationary night blindness. Nat Genet. 1998;19:260–263. doi: 10.1038/940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doering CJ, Hamid J, Simms B, McRory JE, Zamponi GW. Cav1.4 encodes a calcium channel with low open probability and unitary conductance. Biophys J. 2005;89:3042–3048. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick IE, et al. A modular switch for spatial Ca2+ selectivity in the calmodulin regulation of CaV channels. Nature. 2008;451:830–834. doi: 10.1038/nature06529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson BZ, et al. Critical determinants of Ca2+-dependent inactivation within an EF-hand motif of L-type Ca2+ channels. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:1906–1920. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76739-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griessmeier K, et al. Calmodulin is a functional regulator of CaV1.4 l-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.048082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantor CR, Schimmel PR. Biophysical Chemistry: The behavior of biological macromolecules. 11. Macmillan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Ghosh S, Nunziato DA, Pitt GS. Identification of the components controlling inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2004;41:745–754. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong L, Kleerekoper QK, He R, Putkey JA, Hamilton SL. Sites on calmodulin that interact with the C-terminal tail of Cav1.2 channel. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:7070–7079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black DJ, Tran QK, Persechini A. Monitoring the total available calmodulin concentration in intact cells over the physiological range in free Ca2+ Cell Calcium. 2004;35:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slemmon JR, Feng B, Erhardt JA. Small proteins that modulate calmodulin-dependent signal transduction: effects of PEP-19, neuromodulin, and neurogranin on enzyme activation and cellular homeostasis. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;22:99–113. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers JS, Thomas D, Saland L, Neve RL, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43) and synaptophysin alterations in the dentate gyrus of patients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bezprovanny I. Calcium signaling and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2009;15:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masliah E, et al. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee D, Lee SY, Lee EN, Chang CS, Paik SR. alpha-Synuclein exhibits competitive interaction between calmodulin and synthetic membranes. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1007–1017. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan CS, et al. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda S, et al. MicroRNA-1 negatively regulates expression of the hypertrophy-associated calmodulin and Mef2a genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2193–2204. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01222-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.