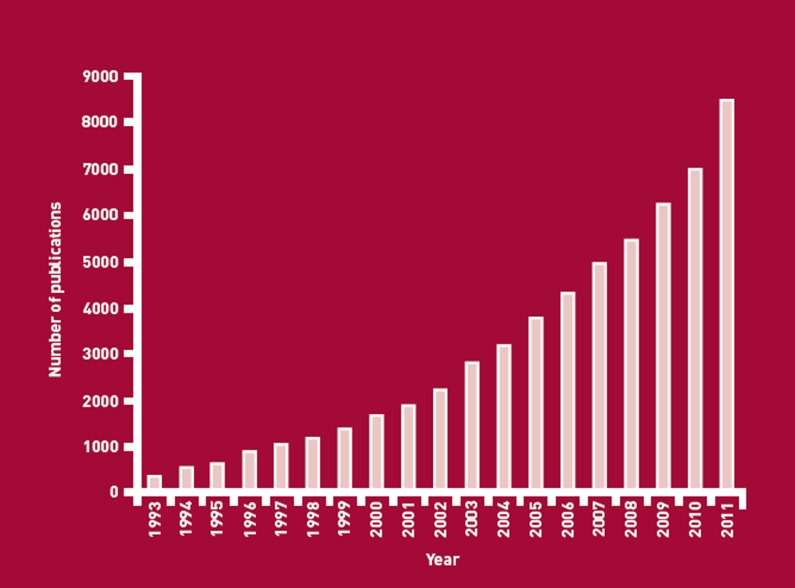

Over the past few years there has been an explosion of interest in the concept of multimorbidity, the existence of multiple longterm conditions in one individual. A search of Medline for papers on multimorbidity or the related term comorbidity reveals that the number of publications on this topic has increased more than twenty fold in the past 20 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of publications on multimorbidity or comorbidity by year.

This level of interest of multimorbidity reflects a growing tension between two opposing trends. Medicine is increasingly focused on helping people to manage longterm conditions rather than treating acute illness, and many people have multiple longterm conditions, and yet medical services are becoming ever more specialised and fragmented. Attention has been paid to improving vertical integration across primary and secondary care using disease pathways for individual conditions such as diabetes or heart failure, but this can be at the expense of holistic coordinated care for people with multiple conditions.

Thanks to all the research over the past two decades we have learnt a great deal about the epidemiology of multimorbidity, the consequences for patients and healthcare professionals of designing systems based on a single disease paradigm, and the adverse impact of multimorbidity on health. We now understand that multimorbidity is extremely common,1 and is particularly prevalent in deprived areas.2 Qualitative studies have shown that providing care for one disease at a time can be inconvenient, inefficient, and unsatisfactory, both for patients with multimorbidity and for healthcare professionals.3–6 It can lead to treatment decisions that are inappropriate and unnecessarily burdensome,7 or to patients seeing many different clinicians, making them feel that there is no one professional who understands them as a ‘whole person’.8 Most importantly, research has highlighted that people with multimorbidity have impaired quality of life, increased morbidity, reduced life-expectancy, and increased rates of depression, and these patients account for a high proportion of resource use in both primary and secondary care.9,10

The time has come to stop just describing the problem of multimorbidity, but to do something about it. Previous research on interventions to improve the management of multimorbidity has been very limited.11 We have enough information now to know what problems need to be solved, and what the priorities should be in redesigning healthcare services. These changes need to start with the way we organise general practice. Although coordinating the care of people with multimorbidity is also a challenge for hospitals, general practice provides the foundation for the organised care of most major long-term conditions.

A new approach to providing care for patients with multimorbidity would have several key ingredients. First, these patients should be specifically identified and their records should be flagged so that they can be managed in a different way and the impact of these changes can be monitored. Second, we should seek to enhance continuity of care for this particular group of individuals with complex needs.12 They are the people who most value and have most to gain from continuity of care, but they are less likely to receive it because of the large number of services they are involved with.1 Continuity could be enhanced by ensuring that each patient with multimorbidity has a clearly designated usual doctor and nurse. Continuity is not only important because patients value having someone they know and trust who understands their needs,12 but also for reasons that patients may not appreciate, since it ensures that one person takes responsibility for coordinating their care. Receptionists should be trained to ensure that patients see their usual doctor, and we should explain to patients the benefits of this, even if it means waiting for an appointment.12 Patients with multimorbidity should be offered longer appointments since they are likely to need to discuss several problems.

We should reorganise our recall systems so that instead of patients being repeatedly recalled to nurse-led chronic disease management clinics to discuss each of their long-term conditions separately they are invited to a regular comprehensive review at which all of their conditions can be reviewed at once. Most practices in the UK use computerised templates to systematise review of each long-term condition, but we need new and more sophisticated templates for these comprehensive reviews that can guide the tasks needed for each patient's particular combination of conditions.

At present, chronic disease reviews are dominated by collection of data needed to achieve targets for disease monitoring set by pay-for-performance schemes such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework. The danger is that these may not reflect the priorities of patients with multimorbidity.8 For these patients, trying to achieve ideal disease control with a view to greater life-expectancy in the future may be a lower priority than improving quality of life now, especially if it requires them to take numerous drugs that cause them unpleasant side-effects. Making these trade-offs can be difficult, and existing evidence based on studies of patients without comorbidities may not provide useful guidance,13 but it is surely important that any review of patients with multimorbidity includes identifying the main problems that affect their quality of life and discussion of these trade-offs.

The comprehensive review for patients with multimorbidity should include screening for and treating depression. We know that multimorbidity is strongly associated with depression, and identifying and treating this effectively helps to improve markers of disease control for physical health problems.14

Patients with multimorbidity are likely to be prescribed large numbers of drugs and the more drugs they are prescribed the less likely they are to take them reliably. Therefore the regular review of patients with multimorbidity should include a serious attempt to reduce and simplify their drug regimens. Although regular medication reviews are already a feature of chronic disease management programmes, these can easily become a ‘tick-box’ exercise. Attempts to reduce polypharmacy through initiatives aimed at doctors or through the involvement of practice-based pharmacists have had only limited success.15 More research is needed on how best to address polypharmacy, and several projects are underway.

How will we know if these approaches to improving the management of multimorbidity are effective? We need large scale and rigorous research, probably based on pragmatic cluster randomised trials which compare general practices that do or do not implement new approaches, including detailed process evaluation and analysis of cost-effectiveness. Outcome measures will need to be broader than simple indicators of disease control, for the reasons mentioned above. The most important outcomes for patients will include improved quality of life, measures of physical and mental health, and their experience of well coordinated, patient-centred care.

Introducing better care for multimorbidity will be a challenge at all levels of the healthcare system. At a national level, policy makers need to promote and incentivise continuity of care rather than speed of access, and measures to improve quality of life rather than just markers of disease control. Commissioners need to support service developments that provide horizontal integration of care for people across multiple disease domains, rather than focusing excessively on improving vertical integration between primary and secondary care within single disease domains. Researchers need to develop interventions based on sound theory and existing evidence about what is likely to work and to test them in rigorous studies. But general practices can make a start by considering how they organise their services, particularly in relation to continuity and coordination of care, in order to improve care for the large and increasing number of people with multimorbidity.

Competing interests

The author has declared no competing interests.

Provenance

Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, et al. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X548929. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp11X548929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett K, Mercer S, Norbury M, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in a large cross-sectional dataset: implications for health care, research and medical education. Lancet. 2012;43(4):497–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noël PH, Frueh BC, Larme AC, Pugh JA. Collaborative care needs and preferences of primary care patients with multimorbidity. Health Expect. 2005;8(1):54–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bower P, Macdonald W, Harkness E, et al. Multimorbidity, service organization and clinical decision making in primary care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2011;28(5):579–587. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith SM, O'Kelly S, O'Dowd T. GPs' and pharmacists' experiences of managing multimorbidity: a ‘Pandora's box'. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(576):285–294. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X514756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luijks HD, Loeffen MJ, Lagro-Janssen AL, et al. GPs' considerations in multimorbidity management: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X652373. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp12X652373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P, et al. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ. 2012;345:e6341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayliss EA, Edwards AE, Steiner JF, Main DS. Processes of care desired by elderly patients with multimorbidities. Fam Pract. 2008;25(4):287–293. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.France EF, Wyke S, Gunn JM, et al. Multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X636146. 10.3399/bjgp12X636146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ. 2012;345:e5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AP, Freeman GK. Promoting continuity of care in general practice. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von KM, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson SM, Hughes C, Kerse N, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub2. CD008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]