Abstract

Background

Management of musculoskeletal conditions in the UK is increasingly delivered in multidisciplinary clinical assessment and treatment services (CATS) at the primary–secondary care interface. However, there is little evidence concerning the characteristics and management of patients attending CATS.

Aim

To describe the characteristics, investigation, and treatment of adults attending a musculoskeletal CATS.

Design and setting

Cross-sectional analysis of cohort study baseline data from a musculoskeletal CATS in Stoke-on-Trent Primary Care Trust, UK.

Method

All patients referred from primary care between February 2008 and June 2009 were mailed a pre-consultation questionnaire concerning pain duration, general health status, anxiety, depression, employment status, and work absence due to musculoskeletal problems. At the consultation, clinical diagnoses, body region(s) affected, investigations, and treatment were recorded.

Result

A total of 2166 (73%) completed questionnaires were received. Chronic pain duration >1 year (55%), major physical limitation (76%), anxiety (49%), and depression (37%) were common. Of those currently employed, 516 (45%) had taken time off work in the last 6 months because of their musculoskeletal problem; 325 (29%) were unable to do their usual job. The most frequent investigations were X-rays (23%), magnetic resonance imaging (18%), and blood tests (14%): 1012 (48%) received no investigations. Injections were performed in 282 (13%) and 492 (23%) were referred to physiotherapy.

Conclusion

Although most patients presented with musculoskeletal problems suitable for CATS, chronic pain, physical limitation, anxiety, depression, and work disability were commonplace, highlighting the need for a biopsychosocial model of care that addresses psychological, social, and work-related needs, as well as pain and physical disability.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, health services, musculoskeletal diseases, referral and consultation, work disability

INTRODUCTION

Musculoskeletal disorders such as back pain and osteoarthritis are highly prevalent and frequently lead to consultation in primary care,1,2 where most are managed. They comprised a considerable proportion of the £16.8 billion that sickness absence from work cost the UK economy in 2009, at an average of 6.4 working days lost per employee.3 Back pain is the most common cause of long-term work absence in manual workers, followed by mental health problems, and other musculoskeletal disorders, and is the third most common cause of long-term work absence among non-manual workers.3 Dame Carol Black’s report Working for a Healthier Tomorrow advocates retention in, or return to, work to be a key indicator of the successful treatment of working-age people.4 Achieving this for the large numbers of patients with musculoskeletal problems poses a major challenge.

For patients with musculoskeletal problems, referral for a specialist opinion has traditionally been to orthopaedic or rheumatology services in secondary care. Recent UK governmental policy has emphasised provision of patient-centred care in services designed around individuals’ needs, which build partnerships between hospitals and general practice.5 Management of musculoskeletal conditions has shifted away from secondary care towards multidisciplinary clinical assessment and treatment services (CATS) at the primary–secondary care interface.6 CATS act as a ‘one-stop shop’ for efficient, rapid assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of patients, yet, crucially, they are also intended to provide holistic care, addressing patients’ psychological, social, and physical needs to enable them to continue working.6 However, there is limited evidence concerning the characteristics of patients referred to CATS, which is needed to inform appropriate resourcing. For example, it is not known whether the majority of patients have simple regional musculoskeletal complaints amenable to treatment with traditional biomedical approaches, or whether they are frequently complicated by chronic symptoms, widespread pain, and psychosocial distress.

Therefore, a prospective cohort study was carried out of patients referred to a musculoskeletal CATS in North Staffordshire, which were cited as an example of good practice in the Department of Health’s Musculoskeletal Services Framework.6 Using baseline data from this cohort, this article describes the musculoskeletal problems addressed in the CATS consultation and the prevalence of physical disability, anxiety, depression, and musculoskeletal-related work absence.

How this fits in

Management of musculoskeletal conditions in the UK has shifted away from secondary care towards multidisciplinary clinical assessment and treatment services (CATS) at the primary–secondary care interface. Although most patients are referred with regional musculoskeletal problems that are appropriate for management in CATS, chronic pain, impaired physical function, anxiety, depression, and work disability are highly prevalent. Musculoskeletal CATS should provide a holistic biopsychosocial model of care that identifies and addresses psychosocial needs and work disability, in addition to pain and physical disability.

METHOD

This study was undertaken using baseline data from a cohort study.7 All participants provided written informed consent.

Study setting

Stoke-on-Trent Primary Care Trust (PCT) serves a population of more than 270 000 people. Since the mid-1990s, the PCT has run a multidisciplinary musculoskeletal service at the primary–secondary care interface, to which secondary care musculoskeletal referrals are triaged following clinical review of referral letters to musculoskeletal, rheumatology, and orthopaedic services. The musculoskeletal service is the preferred provider for patients with non-surgical, non-inflammatory musculoskeletal problems. The triage process aims to manage musculoskeletal conditions requiring non-surgical interventions in the community, while appropriate cases are directed to rheumatology or orthopaedic services.

Data collection

All adults aged ≥18 years seen at this musculoskeletal CATS between February 2008 and June 2009 were invited to participate in the study. Patients were mailed a health questionnaire 2 weeks before the CATS appointment and asked to bring the completed questionnaire with them when they attended clinic. All participants were seen by a research assistant when they attended for the CATS appointment and were given a further opportunity to participate in the study if they had not brought the baseline questionnaire with them. The clinician undertaking the CATS consultation did not have access to the completed health questionnaire.

The questionnaire contained validated health assessment instruments including the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2,8 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),9 and pain duration.10 Data were collected regarding age, sex, postcode, marital status, self-reported height/weight, smoking history (categorised as current, previous, or never), current employment status, absence from work in the preceding 6 months because of musculoskeletal problems, and current work status (categorised as doing usual job, working fewer hours, doing lighter duties, on paid/unpaid sick leave).

Clinical diagnosis (including pain location) addressed during the CATS consultation, investigations requested, treatment prescribed, onward referral, and discharge/follow-up plans were recorded by the clinician conducting the consultation.

Analysis

Age, sex, and neighbourhood deprivation scores, based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2007,11 were compared between study participants and non-participants. Non-participants included those who did not attend their CATS appointment and those who attended but did not wish to participate. Age, sociodemographic data, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI) were summarised for study participants as a whole.

Participants were categorised into four mutually exclusive groups according to the location(s) of the problem addressed in the CATS consultation: upper limb/neck only, spine only, lower limb only, or multiple sites. Pain was considered to be multisite when the clinician recorded either more than one location (upper limb/neck, spine, lower limb) or a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, generalised osteoarthritis, or polymyalgia rheumatica.

Investigations requested, joint injections performed, referral to physiotherapy and pain clinics, and discharge/follow-up planning (discharged to GP, follow-up appointment made, follow-up appointment pending results of investigations) were summarised and compared by pain location (upper limb/neck only, spine only, lower limb only, or multiple sites), using χ2 tests.

Pain duration was categorised as less than 3 months, 3–12 months, 1–2 years, 3–10 years, and > 10 years. Mean scores and standard deviations (SDs) for the eight domains of the SF-36 were calculated and normalised, using the general population mean of 50 (SD = 10) and the conventional scoring.8 Major physical limitation was defined as responding ‘Yes, limited a lot’, the worst response category, to any one of the 10 items comprising the SF-36 physical function scale (PF-10).12 Probable anxiety and depression were defined as a score of > 11 on the anxiety and depression subscales of the HADS respectively: scores 8–10 were considered borderline.9

Current employment was defined as either having a full-time or part-time paid job, or being employed but being currently off sick for 6 months or less. Among those in current employment, the proportions of participants who reported time off work during the preceding 6 months because of musculoskeletal problems, and currently not doing their usual job (working fewer hours, doing lighter duties, or being on paid or unpaid sick leave) were calculated.

The proportion of participants within each category of pain duration, and those reporting major physical limitation, anxiety, depression, and work absence were calculated for the whole study population, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Sample size

Sample size was based on the number of patients (approximately 3500) who are referred to the musculoskeletal and back pain interface clinics in Stoke-on-Trent PCT during the course of a year. Based on the authors’ previous studies, it was expected that 75% of those invited to the study would participate.13 The resulting sample size of 2500 would, for example, allow a 95% CI of ±2%, based on estimated prevalences of 50% for chronic pain and major physical limitation.

RESULTS

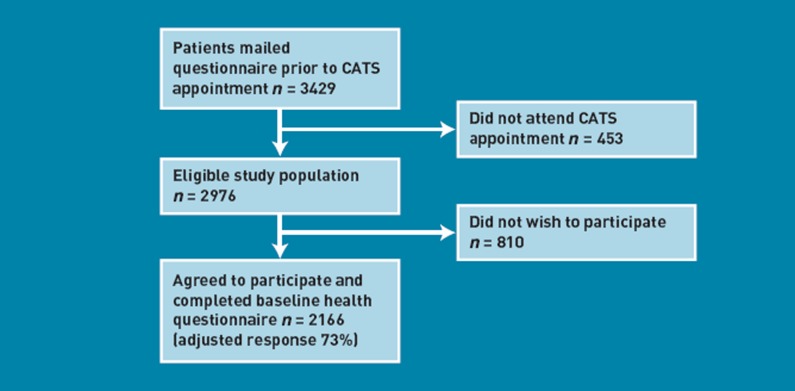

A total of 3429 patients were mailed the questionnaire; 453 (13%) did not attend their CATS appointment. Of the remainder, 2166 completed questionnaires were received (adjusted response 73%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Sociodemographics

There were no differences in mean age or median neighbourhood deprivation scores between those who participated and those who did not take part or did not attend. However, there was a lower percentage of males in the group who participated (43% versus 47%, P = 0.011).

The sociodemographic characteristics, smoking status, and BMI of participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data, smoking status, and body mass index of the cohort

| Characteristic, total n = 2166 | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 51.1 (15.2) |

| Age group, years, n (%) | |

| 18–44 | 750 (35) |

| 45–64 | 992 (46) |

| ≥65 | 424 (20) |

| Female, n (%) | 1238 (57) |

| Living arrangements, n (%) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 1530 (71) |

| Living alone | 322 (15) |

| BMI, n (%)a | |

| Normal/underweight (< 25 kg/m2) | 631 (30) |

| Overweight (25–30 kg/m2) | 792 (38) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 674 (32) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Never smoked | 989 (46) |

| Previously smoked | 682 (32) |

| Current smoker | 493 (23) |

BMI = body mass index. BMI data were missing for 69 (3%) participants. Missing data for all other variables < 1%.

Pain location and diagnosis

Most patients were diagnosed with a musculoskeletal problem considered suitable for an interface service: rheumatological problems (such as inflammatory arthritis, connective tissue disease or polymyalgia rheumatica) and ‘red flag’ pathologies such as malignancy were infrequently encountered (58 patients, 3% and 11 patients, < 1% respectively). The lower limb was the site most frequently addressed in the CATS consultation (656 patients, 31%, 95% CI = 29% to 33%), followed by the upper limb and neck (607 patients, 29%, 95% CI = 27% to 31%), spine (537 patients, 25%, 95% CI = 23% to 27%), and multiple sites (221 patients, 10%, 95% CI = 9% to 12%). The remaining patients were generally given specific diagnoses with no site specified, such as gout, inflammatory arthritis, and joint hypermobility.

The most common diagnoses at each site are shown in Table 2. Combining diagnoses across all joint sites, 487 participants (23%, 95% CI = 21% to 25%) received a diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

Table 2.

Most frequent diagnoses made at each joint sitea

| Neck, n (%) | Shoulder, n (%) | Elbow, n (%) | Hand and wrist, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 183 | Total | 291 | Total | 68 | Total | 233 |

| Neck pain without referral to the arm | 151 (83) | Subacromial pathology | 179 (62) | Epicondylitis | 45 (66) | Carpal tunnel syndrome | 95 (41) |

| Neck pain with referral to the arm | 36 (20) | Glenohumeral OA/frozen shoulder | 78 (27) | Other | 24 (35) | OA (nodal, radiocarpal, first CMCJ) | 58 (25) |

| Other | 9 (5) | Acromioclavicular OA | 40 (14) | Tendon problems (trigger finger, de Quervains’ tenosynovitis) | 48 (21) | ||

| Other | 23 (8) | Other | 45 (19) | ||||

| Spine, n (%) | Hip, n (%) | Knee, n (%) | Foot and ankle, n (%) | ||||

| Total | 615 | Total | 142 | Total | 514 | Total | 141 |

| Low back pain without referral to the leg | 286 (47) | OA | 75 (53) | OA | 289 (56) | Achilles pathology and plantar fasciitis | 42 (30) |

| Low back pain with referral to the leg | 233 (38) | Trochanteric bursitis | 40 (28) | Menisceal pathology | 114 (22) | Ankle problems (ligament injury, instability, tendonitis/tendinopathy) | 38 (27) |

| Spinal stenosis | 41 (7) | Other | 31 (22) | Anterior knee pain | 43 (8) | Mid-foot OA/flat feet | 29 (20) |

| Other | 79 (13) | Ligament pathology (cruciate, collateral) | 41 (8) | Forefoot problems (Morton’s neuroma, hallux valgus, first MTPJ OA) | 23 (16) | ||

| Other | 75 (15) | Other | 24 (17) |

CMCJ = carpometacarpal joint. MTPJ = metatarsophalangeal joint. OA = osteoarthritis. Column totals add up to greater than 100% as some participants have more than one diagnosis recorded.

Investigations, interventions, referrals, and follow-up

Investigations requested, interventions undertaken, onward referral, and plans for discharge and/or follow-up are shown in Table 3. One thousand and twelve participants (48%, 95% CI = 45% to 50%) did not receive any investigations. X-ray was performed least frequently in the spine only group (8% of the spine group received X-ray), whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (37%) were most frequently requested in this group. Blood tests were most frequently requested in the multiple site group (32%). Both electrophysiological tests and diagnostic ultrasound were most frequently requested in the upper limb/neck only group. Corticosteroid injections were performed in 282 participants (13%, 95% CI = 12% to 15%) and were most frequent in the upper limb/neck only group (25%). Four hundred and ninety-two participants were referred to physiotherapy (23%, 95% CI = 21% to 25%) but this did not appear to differ by pain location (P = 0.93). Referrals to pain clinics were infrequent (2%) but were most frequent in those with pain at multiple sites (P < 0.001). Referral rates to orthopaedics and rheumatology were low (151 [7%] and 60 [3%] respectively).

Table 3.

Frequency of investigations, interventions, referrals, and follow-up by location of the problem

| Total | Upper limb/neck | Spine | Lower limb | Multiplea | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2130 | 607 | 537 | 656 | 221 | |

| Investigations, n (%) | ||||||

| X-ray | 475 (22) | 146 (24) | 45 (8) | 174 (27) | 74 (33) | < 0.001 |

| MRI | 393 (18) | 47 (8) | 199 (37) | 124 (19) | 14 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Blood test | 308 (14) | 78 (13) | 69 (13) | 48 (7) | 70 (32) | < 0.001 |

| Electrophysiological tests | 138 (6) | 108 (18) | 5 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 17 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Ultrasound | 96 (5) | 62 (10) | 3 (< 1) | 21 (3) | 4 (2) | < 0.001 |

| No investigation | 1012 (48) | 281 (46) | 276 (51) | 328 (50) | 86 (39) | 0.009 |

| Interventions and referrals, n (%) | ||||||

| Injection | 282 (13) | 152 (25) | 7 (1) | 91 (14) | 28 (13) | < 0.001 |

| Referral to physiotherapy | 492 (23) | 141 (23) | 133 (25) | 154 (23) | 53 (24) | 0.93 |

| Referral to pain clinic | 46 (2) | 2 (< 1) | 15 (3) | 0 (0) | 29 (13) | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up, n (%) | ||||||

| Discharge to GP | 821 (39) | 248 (41) | 162 (30) | 301 (46) | 86 (39) | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up appointment | 208 (10) | 47 (8) | 100 (19) | 35 (5) | 16 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up pending results | 747 (35) | 244 (40) | 162 (30) | 198 (30) | 89 (40) | < 0.001 |

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. More than one location (upper limb/neck, spine, lower limb) recorded or recorded diagnosis of fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, generalised osteoarthritis, or polymyalgia rheumatica.

Comparison across location of problem.

Eight hundred and twenty-one participants were discharged to the care of their GP at this appointment (39%, 95% CI = 37% to 41%). Discharge was highest in the lower limb group (46%) and lowest in the spine group (30%). A follow-up appointment in the interface service was arranged for 208 participants at this appointment (10%, 95% CI = 9% to 11%), with the decision to discharge or follow-up awaiting the results of investigations in a further 747 participants (35%, 95% CI = 33% to 37%).

Health status and work absence

Pain duration, physical limitation, anxiety, depression, and work absence are shown in Table 4. Pain duration was greater than 1 year in 1202 participants (55%, 95% CI = 53% to 58%). Individual SF-36 domain scores were below the general population norm of 50 for all eight domains. The largest deviations from the population norm were seen for the physical function, role limitations (physical), bodily pain, and social functioning domains. Major physical limitation was reported by 1651 participants (76%, 95% CI = 75% to 78%). One thousand and sixty participants (49%, 95% CI = 47% to 51%) had symptoms of anxiety: 619 probable cases (29%), with a further 441 borderline cases (20%). Eight hundred (37%, 95% CI = 35% to 39%) had symptoms of depression: 380 probable cases (18%) and 420 borderline cases (19%). One thousand one hundred and thirty-six participants were in current employment (53%], 95% CI = 51% to 55%). Of these, 516 (45%, 95% CI = 43% to 48%) had taken time off work in the last 6 months because of their musculoskeletal problem, and 325 (29%, 95% CI = 26% to 31%) were unable to do their usual job.

Table 4.

Pain duration, physical limitation, anxiety, depression, and work absence

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Pain duration, n (%) | |

| Less than 3 months | 310 (14) |

| 3–12 months | 650 (30) |

| 1–2 years | 424 (20) |

| 3–10 years | 510 (24) |

| >10 years | 268 (12) |

| SF-36 domain, mean (SD) | |

| Physical function | 36.5 (12.0) |

| Role limitations — physical | 35.7 (12.1) |

| Bodily pain | 34.4 (8.6) |

| General health | 41.5 (11.3) |

| Vitality | 41.5 (11.5) |

| Social functioning | 38.3 (13.2) |

| Role limitations — emotional | 40.0 (15.4) |

| Mental health | 43.3 (12.3) |

| Major physical limitation, n (%) | 1651(76) |

| Anxiety, n (%) | |

| Borderline (HADS 8–10) | 441 (20) |

| Probable case (HADS ≥11) | 619 (29) |

| Depression, n (%) | |

| Borderline (HADS 8–10) | 420 (19) |

| Probable case (HADS ≥11) | 380 (18) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Currently employed | 1136 (53) |

| Time off work because of musculoskeletal problems in the preceding 6 months | 516 (45] |

| Ability to perform usual job, n (%) | |

| Currently performing usual job | 811 (71) |

| Working fewer hours | 65 (6) |

| Doing lighter duties | 125 (11) |

| On paid sick leave | 108 [10] |

| On unpaid leave | 27 (2) |

Missing data for all variables < 1%.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This is the first study highlighting the complexity of patients referred from primary care to multidisciplinary musculoskeletal CATS. The findings demonstrate the significant impact of musculoskeletal problems, with over three-quarters of patients reporting major physical limitation. The infrequency of ‘red flag’ pathologies emphasises the importance of effective clinical triage of referral letters, which, in the CATS used here, is carried out by clinically trained personnel. The underlying principle of this model of care, that most patients with musculoskeletal pain can be managed in a ‘one-stop shop’ without referral to expensive secondary care services, appears to be borne out by the small proportions requiring follow-up or referral to orthopaedics or rheumatology. However, this approach might be open to question, given the complexity of these patients, with high prevalences of chronic pain, impaired quality of life, and anxiety and depressive symptoms. More than half of patients required further investigation, 13% received local corticosteroid injections, and 23% were referred to physiotherapy. Despite high prevalences of chronic pain, anxiety, and depression, only 2% were referred to specialist pain clinics, suggesting that psychosocial issues are under-recognised and under-treated, and that CATS clinicians need to be appropriately trained in the biopsychosocial model of pain. Importantly, substantial absence from work was identified. Of those in current employment, almost half had taken time off work because of musculoskeletal problems in the preceding 6 months, and 29% were unable to perform their usual job.

Strengths and limitations

The study had a high response rate, with 73% of persons who attended their CATS appointment agreeing to participate. An additional strength is that it included consecutive adults attending the CATS, aged ≥18 years, irrespective of their presenting musculoskeletal problems. This study demonstrates the feasibility of collecting outcome data for research purposes in routine clinical practice, supporting the collection of patient-reported outcome measures described in recent healthcare policy documents.5,14

There are two main limitations of the study. First, the study population was derived from one locality, so the findings might not be representative of patients attending CATS in other geographical regions. This locality is one of fairly high socioeconomic deprivation. Rates of obesity, anxiety, depression, and work disability might therefore reflect trends in the local population rather than being specific to this cohort. The prevalence of obesity in this cohort is above the UK national average, whereas the prevalence of smoking is consistent with the national picture.15 Differences between the configuration of CATS services and referral pathways in different areas might limit the generalisability of the study findings. Nevertheless, the CATS used was highlighted in the Musculoskeletal Services Framework as a successful model of interface care,6 and is broadly consistent with the design of musculoskeletal services proposed therein. Secondly, the study did not include a comparator cohort that would allow this musculoskeletal CATS to be compared to more traditional musculoskeletal services such as orthopaedics and rheumatology. Although this musculoskeletal CATS is the preferred local provider for patients with non-surgical, non-inflammatory musculoskeletal problems, at the time of the study, direct referrals into rheumatology and orthopaedic clinics were possible, potentially reducing the generalisability of the findings. One further caveat is that the study did not collect data pertaining to waiting times to the first CATS appointment, which might influence attendance and psychosocial issues.

Comparison with existing literature

Owing to the novelty of musculoskeletal CATS in the UK, there are no suitable cohorts based at the primary–secondary care interface with which the study findings can be compared. A recent evaluation of a physiotherapist-led musculoskeletal clinical assessment service did not assess anxiety, depression, or work absence.16The prevalences of anxiety and depression in the study cohort are higher than those reported in general population samples,17,18 and in those suffering from neck/upper limb pain.19 They are similar to studies of people consulting with musculoskeletal problems in primary care,20,21 and with musculoskeletal problems (including inflammatory arthritis) in secondary care.22–24 The findings are consistent with previous studies showing high levels of work absence in those consulting in primary care in the UK for back pain,20,25 and those suffering from low back pain in the Netherlands who are referred to rehabilitation centres.26Overall, the study provides empirical evidence about the high frequency of anxiety, depression, and work absence in patients consulting with non-inflammatory musculoskeletal problems at the primary–secondary care interface, highlighting the importance of recognising and tackling these important issues in this setting.

Implications for research and practice

The high prevalences of chronic pain, anxiety, depression, and work disability provide insight into the nature and range of support services needed, and, crucially, the importance of providing appropriate training for health professionals to deliver a biopsychosocial model of care. The prevalence of work absence due to musculoskeletal problems supports the need for healthcare professionals to recognise retention in, or return to, work as a key indicator of the successful treatment of working-age people advocated by Working for a Healthier Tomorrow,4 and raises the question as to whether specific vocational rehabilitation programmes should be incorporated into care pathways at the primary–secondary care interface.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people who contributed to the management and/or administration of the study, either at the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre or Stoke-on-Trent PCT: Joanne Bailey, Helen Duffy, Tina Gilbert, Rhian Hughes, Zoë Mayson, Janet Ough, Diane Stanyer, Vicki Taylor, and Sue Weir. Dr Andrew Hassell led the funding application. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contribution of the research nurse teams at the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre and Haywood Hospital, and the clinicians within Stoke-on-Trent PCT musculoskeletal and back pain interface services to data acquisition.

Funding

This work is supported by an Arthritis Research UK Integrated Clinical Arthritis Centre Grant (17684), the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre Grant (18139), funding secured from Stoke-on-Trent PCT, and service support through the West Midlands North CLRN.

Ethical approval

South Staffordshire Local Research Ethics Committee (REC reference number: 07/H1203/86) approved the study.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Jordan K, Jinks C, Croft P. A prospective study of the consulting behaviour of older people with knee pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(525):269–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan K, Kadam U, Hayward R, et al. Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1):144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Confederation of British Industry. On the path to recovery: absence and workplace health survey 2010. London: Confederation of British Industry; 2010. http://www.midlandconstructionsafety.com/index_files/pdf/aspire3.pdf (accessed 11 Dec 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London: TSO; 2008. http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/hwwb-working-for-a-healthier-tomorrow.pdf (accessed 11 Dec 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. Cm7881. London: DoH; 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_117794.pdf (accessed 11 Dec 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. The Musculoskeletal Services Framework. A joint responsibility: doing it differently. London: DoH; 2006. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4138412.pdf (accessed 11 Dec 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roddy E, Zwierska I, Dawes P, et al. The Staffordshire Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Back Assessment (SAMBA) study: a prospective observational study of patient outcome following referral to a primary–secondary care musculoskeletal interface service. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vet HC, Heymans MW, Dunn KM, et al. Episodes of low back pain: a proposal for uniform definitions to be used in research. Spine. 2002;27(21):2409–2416. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000030307.34002.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department for Communities and Local Government. The English indices of deprivation 2010. London: Department for Communities and Local Government; 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/6871/1871208.pdf (accessed 11 Dec 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose MS, Koshman ML, Spreng S, Sheldon R. Statistical issues encountered in the comparison of health-related quality of life in diseased patients to published general population norms: problems and solutions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(5):405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn KM, Jordan K, Lacey RJ, et al. Patterns of consent in epidemiologic research: evidence from over 25,000 responders. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(11):1087–1094. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darzi A High quality care for all. NHS Next Stage review final report. Cm7432. London: Department of Health; 2008. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085825 (accessed 11 Dec 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health and Social Care Information Centre. Health Survey for England — 2011. Adult Trend Tables. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=10152&topics= 1%2fPublic+health%2fLifestyle&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1#top (accessed 8 Jan 2013)

- 16.Sephton R, Hough E, Roberts SA, Oldham J. Evaluation of a primary care musculoskeletal clinical assessment service: a preliminary study. Physiotherapy. 2010;96(4):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, Taylor EP. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40(4):429–434. doi: 10.1348/014466501163904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lisspers J, Nygren A, Soderman E. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD): some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96(4):281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Windt D, Croft P, Penninx B. Neck and upper limb pain: more pain is associated with psychological distress and consultation rate in primary care. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(3):564–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn KM, Croft PR. Classification of low back pain in primary care: using ‘bothersomeness' to identify the most severe cases. Spine. 2005;30(16):1887–1892. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000173900.46863.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallen CD, Peat G. Screening older people with musculoskeletal pain for depressive symptoms in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(555):688–693. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X342228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeley P, Creed F, Tomenson B, et al. Psychosocial predictors of health-related quality of life and health service utilisation in people with chronic low back pain. Pain. 2008;135(1–2):142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hider SL, Tanveer W, Brownfield A, et al. Depression in RA patients treated with anti-TNF is common and under-recognized in the rheumatology clinic. Rheumatology. 2009;48(9):1152–1154. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healey EL, Haywood KL, Jordan KP, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis and its impact on sexual relationships. Rheumatology. 2009;48(11):1378–1381. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wynne-Jones G, Dunn KM, Main CJ. The impact of low back pain on work: a study in primary care consulters. Eur J Pain. 2008;12(2):180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smeets RJ, Wittink H, Hidding A, Knottnerus JA. Do patients with chronic low back pain have a lower level of aerobic fitness than healthy controls? Are pain, disability, fear of injury, working status, or level of leisure time activity associated with the difference in aerobic fitness level? Spine. 2006;31(1):90–97. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192641.22003.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]