Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus causes a wide range of infectious diseases in humans and various animal species. Although presumptive host-specific factors have been reported, certain genetic lineages seem to lack specific host tropism, infecting a broad range of hosts. Such Extended-Host-Spectrum Genotypes (EHSGs) have been described in canine infections, caused by common regional human methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) lineages. However, information is scarce about the occurrence of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) EHSGs. To gain deeper insight into EHSG MSSA and EHSG MRSA of human and canine origin, a comparative molecular study was carried out, including a convenience sample of 120 current S. aureus (70 MRSA and 50 MSSA) isolates obtained from infected dogs. spa typing revealed 48 different spa types belonging to 16 different multilocus sequence typing clonal complexes (MLST-CCs). Based on these results, we further compared a subset of canine (n = 48) and human (n = 14) strains, including isolates of clonal complexes CC5, CC22, CC8, CC398, CC15, CC45, and CC30 by macrorestriction (pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [PFGE]) and DNA-microarray analysis. None of the methods employed was able to differentiate between clusters of human and canine strains independently of their methicillin resistance. In contrast, DNA-microarray analysis revealed 79% of the 48 canine isolates as carriers of the bacteriophage-encoded human-specific immune evasion cluster (IEC). In conclusion, the high degree of similarity between human and canine S. aureus strains regardless of whether they are MRSA or MSSA envisions the existence of common genetic traits that enable these strains as EHSGs, challenging the concept of resistance-driven spillover of MRSA.

INTRODUCTION

Since the early 1980s, potentially host-specific ecovars of Staphylococcus aureus strains have been an ongoing subject of scientific discourse (1, 2).

In recent years, comparative molecular analysis of S. aureus isolates from different hosts determined differences on the genome level for some lineages, indicating the occurrence of host-specific genotypes (3, 4) or tissue tropism (5). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) revealed clonal complexes (CC) associated with specific hosts in different studies (4, 6, 7). Ruminants in particular seem to harbor S. aureus belonging to sequence types (ST) which are rarely found among humans (8). In addition, mobile genetic elements (MGEs) were found to harbor putative host-specific virulence-associated factors which may play a role during S. aureus infections in a certain host. For example, variants of S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPI) such as SaPIbov or SaPIequ harbor genes encoding a von Willebrand factor-binding protein paralogue which enhances coagulation activity of the pathogen in bovine or equine plasma (9). Moreover, the phage-encoded immune evasion cluster (IEC) is described as a human-specific element comprising various combinations of the following proteins and corresponding genes: the staphylococcal complement inhibitor (scn), the plasminogen activator staphylokinase (sak), the chemotaxis inhibitory protein (chp), and the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A (sea). Different studies reported high IEC carriage rates among human S. aureus strains (10, 11), while the IEC was less frequently detected in strains of animals, especially those of ruminant origin (6, 10, 12).

S. aureus strains which harbor the mecA gene (methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]) encoding methicillin resistance have been identified among humans as well as in companion animals and in livestock. MLST analysis of MRSA showed that dogs in particular are predominantly infected with common regional lineages of human origin, like sequence type 22 (ST22) and ST5 (13–17). Moreover, different reports revealed MRSA strains of canine and human origin with indistinguishable macrorestriction patterns by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis (18–21), indicating a cross-species transmission. Such genetic lineages with the ability to infect several different animal species as well as humans were denominated extended-host-spectrum genotypes (EHSG) (22).

While recent literature has focused on the characterization of EHSG MRSA, scarce information is provided concerning the comparative analysis of human and canine methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), even though identical lineages have been reported in humans and dogs living in the same household, indicating a zoonotic potential (23).

The purpose of this study was therefore to investigate the genetic background of canine MRSA and MSSA representing different geographic origins (mainly Germany) and infection sites. Further, several representatives of each genotype detected among the canine isolates were selected for a broad comparative analysis, including human isolates sharing the same genetic background, using DNA-microarray analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Canine strains, verification of S. aureus, and detection of methicillin resistance.

A convenience sample of 120 canine S. aureus strains, isolated from various infection sites between 2000 and 2011 and identified and collected in veterinary diagnostic laboratories (Vet Med Labor GmbH, Ludwigsburg, Germany; Institute of Microbiology and Epizootics; Synlab, Augsburg, Germany), was stored in glycerol stocks at −80°C. In order to rule out simple contamination of the infection site, information about the culturing process and semiquantitative data on each positive S. aureus specimen as well as information on further bacterial species detected in some of the samples are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The majority of strains were isolated in Germany (10 different federal states), whereas 26 strains originated from nine other European countries: Austria (6 isolates), Italy (5 isolates), France (5 isolates), Netherlands (4 isolates), Sweden (2 isolates), Denmark (1 isolate), Luxembourg (1 isolate), Norway (1 isolate), and Spain (1 isolate) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Three isolates came from an unknown geographical origin. All isolates were verified as S. aureus, and methicillin resistance was detected according to the presence of mecA using a protocol described by Merlino et al. (27).

Baseline molecular typing of canine S. aureus strains.

All isolates were typed by sequencing the tandem repeat region of the staphylococcal protein A-encoding gene (spa) (28). Associations with corresponding clonal complexes (MLST-CCs) were determined by the use of the ridom spa server (http://www.ridom.de/) as described before (29). In total, 58 canine isolates with at least one representative strain of each spa type were investigated by DNA-microarray hybridization of 334 distinct genetic loci using an Alere Identibac S. aureus Genotyping chip according to previously described protocols and procedures (6). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed for selected isolates representing distinct spa types (26).

Comparative molecular analysis of representative canine and human S. aureus strains.

In total, 14 human strains (provided by S. Monecke, Technical University of Dresden, Dresden, Germany/Alere Technologies GmbH, Jena, Germany; W. Witte, Robert-Koch-Institut, Wernigerode, Germany; and the Institute of Microbiology, Free University Berlin, Berlin, Germany) were included for comparative analysis with 48 canine strains from each CC comprising more than three isolates.

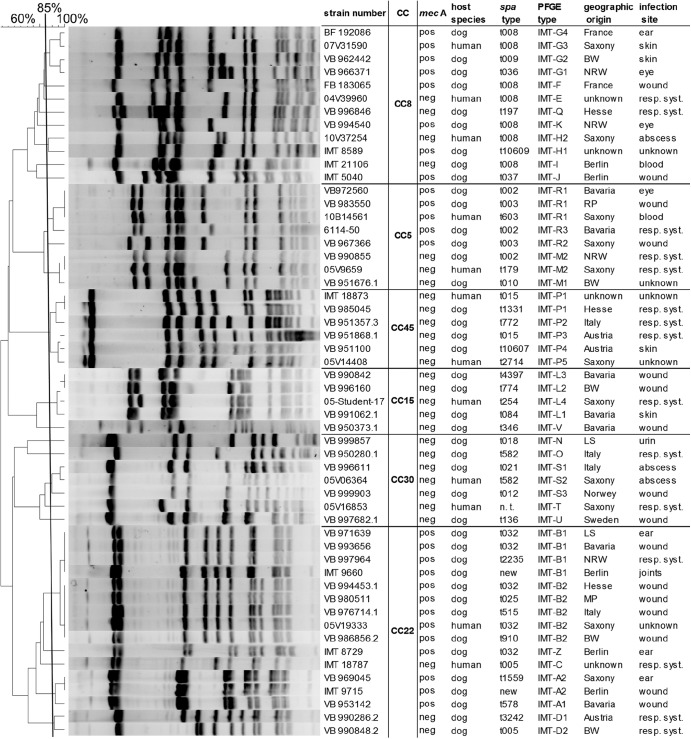

Macrorestriction analysis of chromosomal DNA using endonuclease SmaI followed by comparative analysis of the resulting PFGE pattern was carried out employing BioNumerics version 6.5 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) (Dice coefficient [tolerance, 1.2%; optimization, 0.5%]) as described before (22). Isolates with ≥85% similarity according to the dendrogram were considered to belong to a group of clonally related strains (indicated with capital letters). Subgroups were denominated by numbers within each group (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Macrorestriction analysis of representative canine and human isolates. SmaI macrorestriction patterns are shown with a dendrogram (cluster analysis; Dice coefficient [1.2% tolerance and 0.5% optimization]) displaying 43 canine and 12 human isolates with spa type, PFGE type, and host origin. Strains are grouped into clonal complexes according to the spa type and macrorestriction pattern. Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; BW, Baden Wuerttemberg, Germany; MP, Mecklenburg Pomerania, Germany; NRW, North Rhine Westphalia, Germany; RP, Rhineland Palatinate, Germany; LS, Lower Saxony, Germany; resp. syst., respiratory system; n.t., not typed; pos, positive; neg, negative.

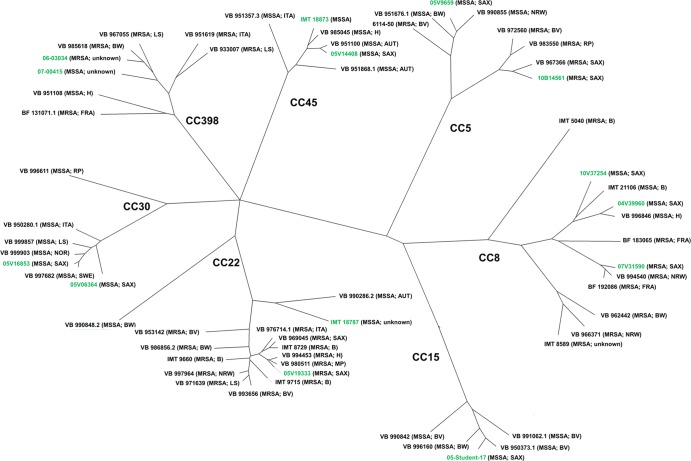

A rendered tree was calculated based on microarray hybridization results after BioNumerics cluster analysis of the data using Pearson correlation and the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) (see Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Rendered tree based on the microarray hybridization results of 334 target sequences after cluster analysis of the data performed using Pearson correlation and UPGMA. Canine isolates are black; human strains are highlighted in green. The branch lengths display the percentages of different loci in comparison to other isolates. Each strain is shown with its geographic origin. B, Berlin, Germany; BV, Bavaria, Germany; BW, Baden Wuerttemberg, Germany; H, Hesse, Germany; LS, Lower Saxony, Germany; MP, Mecklenburg Pomerania, Germany; NRW, North Rhine Westphalia, Germany; RP, Rhineland Palatinate, Germany; SAX, Saxony, Germany; AUT, Austria; FRA, France; ITA, Italy; NEL, Netherlands; NOR, Norway; SWE, Sweden.

RESULTS

Clonal background of the canine S. aureus isolates.

spa typing of 120 S. aureus strains (70 MRSA, 50 MSSA) revealed 47 different spa types associated with 16 different CCs (Table 1) according to http://www.ridom.de/, microarray analysis, or multilocus sequence typing results. While 40 isolates belonged to CC5 (t003, t002, and t010), 27 were assigned to CC22 (t032, t005, t025, t515, t578, t910, t1559, t2235, and t3242), 14 to CC8 (t008, t009, t036, t037, t197, and t10609), 9 to CC45 (t015, t772, t1331, and t10607), 7 to CC398 (t011, t034, t889, t3081, and t6867), and 5 to CC30 (t012, t018, t021, t136, and t582). Five CC15 isolates were represented by spa types t084, t254, t346, and t4397. The remaining 12 isolates belonged to 10 different CCs (CC1, CC6, CC7, CC12, CC25, CC59, CC72, CC101, CC121, and CC188) (Table 1). All MRSA isolates were identified within CC5, CC22, CC8, or CC398, while MSSA isolates were assigned to 17 different CCs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of canine strains used in this study

| CCa | All S. aureus strains (n = 120) |

Selected S. aureus strains |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of strains | spa type | No. of MRSA strains | No. of MSSA strains | Microarray hybridization |

No. of strains with MLST results | ST | ||

| No. of MRSA strains | No. of MSSA strains | |||||||

| 5 | 17 | t002 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| 21 | t003 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 225 | |

| 2 | t010 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| 22 | 1 | t005 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| 1 | t025 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 16 | t032 | 16 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 22 | |

| 1 | t515 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t578 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | t910 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 22 | |

| 1 | t1559 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t2235 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 22 | |

| 1 | t3242 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 22 | |

| 8 | 8 | t008 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | t009 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 254 | |

| 1 | t036 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t037 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 239 | |

| 1 | t197 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| 1 | t10609 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 254 | |

| 45 | 6 | t015 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 45 |

| 1 | t772 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 45 | |

| 1 | t1331 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t10607 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 45 | |

| 398 | 3 | t011 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 398 |

| 1 | t034 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t899 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t3081 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t6867 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 15 | 2 | t084 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| 1 | t254 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t346 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | t4397 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 | |

| 30 | 1 | t012 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1 | t018 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 30 | |

| 1 | t021 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 30 | |

| 1 | t136 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 34 | |

| 1 | t582 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | SLV 30 | |

| 7 | 3 | t091 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 121 | 1 | t159 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1 | t1425 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | t127 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | t207 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | SLV 6 |

| 12 | 1 | t771 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| 25 | 1 | t6145 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 25 |

| 59 | 1 | t216 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 59 |

| 72 | 1 | t6155 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | SLV 72 |

| 101 | 1 | t1312 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 101 |

| 188 | 1 | t189 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 188 |

CC, clonal complex.

In order to verify the association with CCs using http://www.ridom.de/, 37 representatives were characterized by MLST. While most of these strains showed common STs (ST5, ST225, ST22, ST254, ST239, ST8, ST45, ST398, ST15, ST188, ST30, ST34, ST7, ST1, ST12, ST25, ST59, and ST101), three isolates belonged to new STs, being single-locus variants (SLV) of ST30, ST6, or ST72, respectively (Table 1).

For further molecular analysis, representative S. aureus isolates of each CC comprising more than three isolates (including CC5, CC22, CC8, CC398, CC45, CC15, and CC30) were chosen for comparative molecular analysis with 14 human isolates known to share the same CCs using PFGE analysis as well as DNA-microarray hybridization. Evaluation with a focus on the human-specific immune evasion cluster (IEC) showed a carriage rate of 79% (38/48) among these clinical canine S. aureus isolates.

Comparative analysis of human and canine S. aureus isolates. (i) CC5.

Six canine strains (four MRSA and two MSSA) and two human strains (one MRSA and one MSSA) of CC5 were chosen for comparative analysis using PFGE and DNA-microarray hybridization.

PFGE analysis showed high similarity within the CC5 macrorestriction pattern comprising two different clusters dependent on methicillin resistance. Indistinguishable PFGE patterns displayed by human and canine isolates were found in both clusters (Fig. 1).

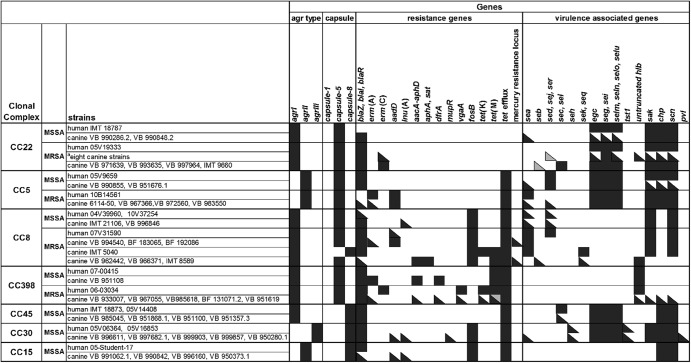

Microarray hybridization results revealed that canine and human CC5 isolates yielded positive signals for genes of the virulence-associated enterotoxin gene cluster (egc) seg, sei, selm, seln, selo, and selu, while sed, sej, and ser were less frequently detected (Fig. 2). All but one canine strain harbored IEC genes (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Microarray hybridization results for agr type and capsule type and a selection of resistance- and virulence-associated genes. Black squares, positive; gray squares, ambiguous results according to Alere DNA-microarray analysis software; divided squares, variable results for individual isolates within grouped strains per lane. The eight canine strains indicated by the superscript “a” among the CC22 MRSA strains are VB 994453.1, VB 980511, VB 976714.1, IMT 8729, VB 969045, IMT 9715, VB 953142, and VB 986856.2.

Six isolates carried the bla resistance operon, excluding the human and one canine MRSA isolate. All MRSA isolates were positive for aadD, a gene encoding aminoglycoside resistance. Among the five MRSA isolates, four harbored staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element type II (SCCmec II; Rhine-Hesse epidemic strain/UK-EMRSA-3) and one SCCmec I variant (Geraldine clone) (canine strain) (Table S2 in the supplemental material). Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL)-positive strains were not detected.

(ii) CC22.

PFGE analysis of 14 representative canine isolates (12 MRSA and 2 MSSA) and 2 human strains (1 MSSA and 1 MRSA) revealed five different clusters (Fig. 1).

The IMT-B2 subgroup pattern, which was closely related to the Barnim epidemic strain (UK-MRSA-15) (22), was identified for four canine MRSA isolates (Fig. 1).

Genes belonging to the egc cluster were detected in all but one canine strain. Furthermore, all but one of the canine strains harbored genes of the IEC, while genes encoding the staphylococcal enterotoxins SEC and SEL were identified only infrequently in three canine isolates. One canine isolate yielded a positive result for staphylococcal enterotoxin A. PVL was not detected.

The bla operon was present in all isolates except for one human MSSA. The erm(C) gene for erythromycin resistance was detected infrequently (n = 8) in canine isolates but missing among the human strains. All MRSA isolates harbored SCCmec IV.

(iii) CC8.

Seven MRSA and two MSSA isolates of canine origin as well as three human isolates (one MRSA and two MSSA) were chosen for comparative analysis of isolates belonging to CC8.

Macrorestriction analysis revealed eight distinct PFGE clusters with a notable resemblance to one human and one canine MRSA isolate within patterns IMT-G3 and G4 (Fig. 1).

Genes of the IEC were present in most of the isolates (negative: three canine isolates). The staphylococcal enterotoxin genes sed, sej, and ser as well as seb, sek, and seq were found infrequently. All CC8 isolates were negative for pvl.

The bla operon was identified in all but one canine and one human isolate. Resistance-encoding genes aadD, aacA-aphD, and aphA3 (aminoglycoside resistance), lnu(A) (lincosamide resistance), tet(M) and tet(K) (tetracycline resistance), and erm(A) and erm(C) (erythromycin resistance) as well as qacC (resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds) were infrequently detected.

Four MRSA isolates harbored SCCmec IV, while one canine isolate (ST239-MRSA) carried SCCmec III. Three strains yielded positive signals for the truncated mecR as well as ugpQ and Q9XB68-dcs and harbored an atypical SCCmec according to the microarray hybridization results.

Additionally, one MSSA isolate was positive for ccrB-4, part of a chromosomal cassette.

(iv) CC398.

Five canine MRSA isolates and one canine MSSA isolate were chosen for further investigation and compared to two human isolates (one MRSA and one MSSA) within CC398. All isolates were not typeable (NT) by PFGE following digestion with SmaI.

CC398-associated strains lacked most of the tested virulence-associated genes, except one canine isolate, which carried the IEC.

All isolates harbored the bla resistance operon and were positive for tet(M). One canine and one human MRSA yielded positive signals for tet(K) as well. The resistance-encoding genes dfrA (trimethoprim resistance), erm(A), erm(C), aacA-aphD, and vga (streptogramin resistance) were not detected frequently (Fig. 2).

Signals corresponding to two different SCCmec types (IV and V) were obtained from most CC398 isolates, while one mecA-positive isolate could not be further characterized using an Alere Identibac S. aureus Genotyping chip. It yielded positive signals for mecA and ugpQ (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

(v) CC45.

Four canine MSSA isolates were chosen for further analysis by PFGE and DNA-microarray hybridization for comparisons that included two representative human MSSA isolates.

PFGE analysis revealed more than 85% similarity for all investigated isolates and further showed indistinguishable macrorestriction patterns (IMT-P1) for one human and one canine isolate.

Components of the egc and the IEC were detected in all isolates, while the enterotoxin-encoding genes sec and sel were identified infrequently.

All isolates yielded positive signals for the bla operon.

(vi) CC30.

Five canine MSSA isolates were compared to two human MSSA strains.

PFGE analysis revealed five distinct macrorestriction patterns with one human and two canine strains belonging to the same cluster (IMT-S).

All isolates carried egc as well as genes of the IEC. The toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 gene (tst) was detected in three canine strains and one human isolate. Two of these isolates (one human and one canine strain) carried seh (ST34-MSSA) as well. A tst-negative canine MSSA strain showed a positive signal for pvl.

The bla operon was present in all isolates. Additionally, one canine strain was positive for aadD, lnu(A), and mupR (mupirocin resistance).

(vii) CC15.

Within CC15, four canine MSSA strains were compared to one human MSSA strain. PFGE analysis revealed two different patterns with three canine strains and the human isolate belonging to IMT-L. According to the microarray results, genes of the IEC were identified in each isolate. All isolates but one (canine) yielded positive signals for the bla operon. One of these strains carried aadD and lnu(A), too.

Rendered tree.

Overall, the comparative analysis of microarray hybridization results (including 334 different gene loci) from 48 canine and 14 human isolates which were visualized in a rendered tree (Fig. 3) revealed a close resemblance for canine and human MRSA and MSSA, regardless of factors such as host, geographic origin, infection site, and isolation time.

DISCUSSION

Molecular typing results for 120 canine S. aureus (MRSA, 70; MSSA, 50) isolates originating from various geographic origins and diseases identified several well-known clonal backgrounds, including common local human lineages as well as the CC398 livestock-associated (LA) lineage. The obvious lack of canine-associated clones among MRSA is in accordance with recent studies which ascertained that MRSA strains isolated from pets belong to the same lineages as the dominant human lineages in each country, indicating a spillover of hospital-associated MRSA from people to their in-contact pets (30). Unexpectedly, even MSSA isolates obtained from infected dogs belonged to clonal backgrounds which are well known for human isolates, indicating the adaptive ability of certain genotypes (extended-host-spectrum genotypes [EHSGs]), regardless of their being MRSA or MSSA. In line with these findings, microarray analysis revealed no specific differences in the frequency and composition of virulence-associated and resistance genes carried by canine S. aureus from those carried by human isolates.

However, the comparative analysis of microarray data gained from human and canine strains mirrors the natural genetic composition and variability within each clonal complex (Fig. 3). For most of the CCs mentioned in this study, comparable variations have been detected before, including the occurrence of certain SCCmec types (31). Our data indicate that the genetic variability between individual MRSA and MSSA strains within each CC does not depend on factors such as host, date of isolation, and geographic origin (Fig. 1).

In particular, with regard to the fact that all isolates originated from infected animals, the idea of the role of putative host-specific factors such as the IEC could also be challenged, since the IEC was detected in 38 (79%) of 48 DNA-microarray-characterized canine isolates (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In a recent study, Verkaik et al. identified S. aureus strains of human (n = 21) origin as main IEC carriers (90%), while only 33.8% of the investigated animal strains (n = 77) tested positive. Animals infected with a “typical human strain” according to amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) genotyping were dogs, cats, rabbits, and horses. These strains clustered together with human strains, and 45.3% of them were IEC positive (12). However, the clonal background (spa type and sequence type) of these strains remains unknown. This report demonstrates the regular occurrence of the IEC among canine isolates that belong to typical human lineages (CC5, CC15, CC22, CC30, and CC45). This finding suggests either that the probability or frequency of the loss of the IEC phages is low or that there might be a potential benefit of IEC genes in at least some nonhuman hosts as well. Furthermore, one canine CC398-associated MRSA strain carried the IEC, leading to the assumption that humans are a possible infection source, since IEC-carrying CC398 MRSA have been reported predominantly in human isolates (32). Even though the effects of IEC genes are described as specific for humans, knowledge is scarce about the expression and functional effects of factors carried on the IEC in dogs. Lijnen et al. compared fibrinolytic and fibrinogenolytic activities of staphylokinase (Sak) in different species and identified high activity in humans as well as in dogs, indicating a potential role of Sak in the canine host as well (33). However, whether the IEC or the mutually exclusive untruncated hlb may possess a beneficial effect in the canine host still needs to be investigated in further experimental studies.

Moreover, PFGE analysis proved the presence of indistinguishable MRSA and MSSA strains in dogs and humans. These results are in accordance with a recent study concerning Japanese canine S. aureus isolates from healthy and infected dogs. The isolated MSSA and MRSA strains predominantly exhibited ST5, a common ST in Japanese health care-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) (39).

In particular, CC22- and CC5-MRSA were frequently associated with canine infections. These MRSA lineages are widely distributed and predominant among human strains in Germany (35). Furthermore, CC8, CC30, and CC45 S. aureus (MRSA and MSSA) strains which were characterized from canine samples had previously been reported for human infections as well (35). While all canine strains of lineages CC30 and CC45 in this study were methicillin susceptible, MRSA strains of these clonal complexes had been described in human infections in Germany as well (35). The absence of canine CC30 and CC45 MRSA might have been an accident due to the sample size. Other possible reasons could be the limited occurrence of these lineages in Germany or the loss of the mecA gene. However, canine CC30 MRSA strains had been reported in the past as well (36).

The isolation of CC398 S. aureus from dogs was reported before (24, 25, 37), which confirms the ability of these strains to adapt to hosts other than livestock or humans. Overall, comparative analysis of canine and human isolates belonging to CC5, CC22, CC15, CC30, and CC45 revealed a remarkable PFGE pattern concordance, although the canine isolates originated from nine German federal states as well as eight further European countries and were collected over a period of 10 years. A close relationship of human and canine S. aureus PFGE patterns besides those obtained during nosocomial outbreaks in veterinary settings has been reported before, in particular for CC22 isolates (15).

With respect to the current proportion of S. aureus strains among canine wound samples being 5.8% (3.6% MRSA; unpublished IMT data), direct human-to-dog transmission might be an important but not the only infection source for canine patients. Although our group has recently reported a low rate (1.8%) of nasal S. aureus carriage in dogs in the community (38), cases of autoinfection seem to be as likely a source of S. aureus infections in colonized dogs as events of transmission between different pets, humans, or contaminated environmental sites. Nonetheless, we demonstrated that each of the canine strains reported here can possibly be found in humans as well, providing evidence for the occurrence of EHSG MSSA and MRSA among diseased dogs. However, a possible host adaptation by alteration of similar surface-associated proteins such as has been reported for CC398 isolates only recently (34) cannot be ruled out by the methods used in this study. Moreover, since companion animals are in contact with the large microbiome and resistome pools of the environment, further (unknown) MGEs may enhance the ability of individual strains to adapt to certain hosts. More detailed genetic information obtained through comparative genome analysis is needed with respect to these issues.

In conclusion, the epidemiology of S. aureus takes many paths, and focusing on a single one might lead to a restricted view influencing intervention strategies (e.g., reinfection of human patients due to colonized or infected pets). The findings of this study strongly demand the strengthening of the “One Health” idea, the tight cooperation of human, animal, and public health sciences.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and is part of the MedVet-Staph project (01KI1014A).

We thank W. Witte (Robert-Koch-Institut, Wernigerode, Germany) for providing the human CC398 isolates and A. Soba (synlab.vet GmbH, Augsburg, Germany) for the canine isolate 6114-50. We also thank E. Antao for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 November 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at 10.1128/AEM.02704-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Devriese LA. 1984. A simplified system for biotyping Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from animal species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 56:215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Devriese LA, Nzuambe D, Godard C. 1984. Identification and characterization of staphylococci isolated from cats. Vet. Microbiol. 9:279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Herron-Olson L, Fitzgerald JR, Musser JM, Kapur V. 2007. Molecular correlates of host specialization in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 2:e1120 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lowder BV, Guinane CM, Ben Zakour NL, Weinert LA, Conway-Morris A, Cartwright RA, Simpson AJ, Rambaut A, Nubel U, Fitzgerald JR. 2009. Recent human-to-poultry host jump, adaptation, and pandemic spread of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19545–19550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Leeuwen WB, Melles DC, Alaidan A, Al-Ahdal M, Boelens HA, Snijders SV, Wertheim H, van Duijkeren E, Peeters JK, van der Spek PJ, Gorkink R, Simons G, Verbrugh HA, van Belkum A. 2005. Host- and tissue-specific pathogenic traits of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:4584–4591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Monecke S, Kuhnert P, Hotzel H, Slickers P, Ehricht R. 2007. Microarray based study on virulence-associated genes and resistance determinants of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 125:128–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smyth DS, Feil EJ, Meaney WJ, Hartigan PJ, Tollersrud T, Fitzgerald JR, Enright MC, Smyth CJ. 2009. Molecular genetic typing reveals further insights into the diversity of animal-associated Staphylococcus aureus. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:1343–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmes MA, Zadoks RN. 2011. Methicillin resistant S. aureus in human and bovine mastitis. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 16:373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Viana D, Blanco J, Tormo-Mas MA, Selva L, Guinane CM, Baselga R, Corpa JM, Lasa I, Novick RP, Fitzgerald JR, Penades JR. 2010. Adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus to ruminant and equine hosts involves SaPI-carried variants of von Willebrand factor-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 77:1583–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sung JM, Lloyd DH, Lindsay JA. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus host specificity: comparative genomics of human versus animal isolates by multi-strain microarray. Microbiology 154:1949–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Wamel WJ, Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. 2006. The innate immune modulators staphylococcal complement inhibitor and chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus are located on beta-hemolysin-converting bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 188:1310–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verkaik NJ, Benard M, Boelens HA, de Vogel CP, Nouwen JL, Verbrugh HA, Melles DC, van Belkum A, van Wamel WJ. 2011. Immune evasion cluster-positive bacteriophages are highly prevalent among human Staphylococcus aureus strains, but they are not essential in the first stages of nasal colonization. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malik S, Coombs GW, O'Brien FG, Peng H, Barton MD. 2006. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant staphylococci isolated from cats and dogs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moodley A, Stegger M, Bagcigil AF, Baptiste KE, Loeffler A, Lloyd DH, Williams NJ, Leonard N, Abbott Y, Skov R, Guardabassi L. 2006. spa typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from domestic animals and veterinary staff in the UK and Ireland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1118–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Strommenger B, Kehrenberg C, Kettlitz C, Cuny C, Verspohl J, Witte W, Schwarz S. 2006. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from pet animals and their relationship to human isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:461–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walther B, Wieler LH, Friedrich AW, Hanssen AM, Kohn B, Brunnberg L, Lubke-Becker A. 2008. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from small and exotic animals at a university hospital during routine microbiological examinations. Vet. Microbiol. 127:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weese JS, Dick H, Willey BM, McGeer A, Kreiswirth BN, Innis B, Low DE. 2006. Suspected transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between domestic pets and humans in veterinary clinics and in the household. Vet. Microbiol. 115:148–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baptiste K, Williams K, Willams N, Wattret A, Clegg P, Dawson S, Corkill J, O'Neill T, Hart C. 2005. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci in companion animals. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1942–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loeffler A, Boag AK, Sung J, Lindsay JA, Guardabassi L, Dalsgaard A, Smith H, Stevens KB, Lloyd DH. 2005. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among staff and pets in a small animal referral hospital in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:692–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manian FA. 2003. Asymptomatic nasal carriage of mupirocin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a pet dog associated with MRSA infection in household contacts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:e26–e28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Duijkeren E, Wolfhagen MJ, Box AT, Heck ME, Wannet WJ, Fluit AC. 2004. Human-to-dog transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:2235–2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walther B, Monecke S, Ruscher C, Friedrich AW, Ehricht R, Slickers P, Soba A, Wleklinski CG, Wieler LH, Lubke-Becker A. 2009. Comparative molecular analysis substantiates zoonotic potential of equine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:704–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanselman BA, Kruth SA, Rousseau J, Weese JS. 2009. Coagulase positive staphylococcal colonization of humans and their household pets. Can. Vet. J. 50:954–958 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haenni M, Saras E, Chatre P, Medaille C, Bes M, Madec JY, Laurent F. 2012. A USA300 variant and other human-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains infecting cats and dogs in France. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:326–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Floras A, Lawn K, Slavic D, Golding GR, Mulvey MR, Weese JS. 2010. Sequence type 398 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection and colonisation in dogs. Vet. Rec. 166:826–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merlino J, Watson J, Rose B, Beard-Pegler M, Gottlieb T, Bradbury R, Harbour C. 2002. Detection and expression of methicillin/oxacillin resistance in multidrug-resistant and non-multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Central Sydney, Australia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothganger J, Turnwald D, Vogel U. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5442–5448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moodley A, Nightingale EC, Stegger M, Nielsen SS, Skov RL, Guardabassi L. 2008. High risk for nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Danish veterinary practitioners. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 34:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loeffler A, Lloyd DH. 2010. Companion animals: a reservoir for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the community? Epidemiol. Infect. 138:595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Monecke S, Berger-Bachi B, Coombs G, Holmes A, Kay I, Kearns A, Linde HJ, O'Brien F, Slickers P, Ehricht R. 2007. Comparative genomics and DNA array-based genotyping of pandemic Staphylococcus aureus strains encoding Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:236–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McCarthy AJ, Witney AA, Gould KA, Moodley A, Guardabassi L, Voss A, Denis O, Broens EM, Hinds J, Lindsay JA. 2011. The distribution of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in MRSA CC398 is associated with both host and country. Genome Biol. Evol. 3:1164–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lijnen HR, Stassen JM, Vanlinthout I, Fukao H, Okada K, Matsuo O, Collen D. 1991. Comparative fibrinolytic properties of staphylokinase and streptokinase in animal models of venous thrombosis. Thromb. Haemost. 66:468–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uhlemann AC, Porcella SF, Trivedi S, Sullivan SB, Hafer C, Kennedy AD, Barbian KD, McCarthy AJ, Street C, Hirschberg DL, Lipkin WI, Lindsay JA, Deleo FR, Lowy FD. 2012. Identification of a highly transmissible animal-independent Staphylococcus aureus ST398 clone with distinct genomic and cell adhesion properties. mBio 3:e00027–12 doi:10.1128/mBio.00027-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robert-Koch-Institut 2011. Epidemiologic bulletin nr. 26.12. Robert-Koch-Institut, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loeffler A, Pfeiffer DU, Lloyd DH, Smith H, Soares-Magalhaes R, Lindsay JA. 2010. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage in UK veterinary staff and owners of infected pets: new risk groups. J. Hosp. Infect. 74:282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Witte W, Strommenger B, Stanek C, Cuny C. 2007. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in humans and animals, Central Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:255–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walther B, Hermes J, Cuny C, Wieler LH, Vincze S, Abou Elnaga Y, Stamm I, Kopp PA, Kohn B, Witte W, Jansen A, Conraths FJ, Semmler T, Eckmanns T, Lübke-Becker A. 2012. Sharing more than friendship—nasal colonization with coagulase-positive staphylococci (CPS) and co-habitation aspects of dogs and their owners. PLoS One 7:e35197 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sasaki T, Tsubakishita S, Tanaka Y, Ohtsuka M, Hongo I, Fukata T, Kabeya H, Maruyama S, Hiramatsu K. 2012. Population genetic structures of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cats and dogs in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2152–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.