Abstract

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 produces the phytotoxin coronatine, a major determinant of the leaf chlorosis associated with DC3000 pathogenesis. The DC3000 PSPTO4723 (cmaL) gene is located in a genomic region encoding type III effectors; however, it promotes chlorosis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana in a manner independent of type III secretion. Coronatine is produced by the ligation of two moieties, coronafacic acid (CFA) and coronamic acid (CMA), which are produced by biosynthetic pathways encoded in separate operons. Cross-feeding experiments, performed in N. benthamiana with cfa, cma, and cmaL mutants, implicate CmaL in CMA production. Furthermore, analysis of bacterial supernatants under coronatine-inducing conditions revealed that mutants lacking either the cma operon or cmaL accumulate CFA rather than coronatine, supporting a role for CmaL in the regulation or biosynthesis of CMA. CmaL does not appear to regulate CMA production, since the expression of proteins with known roles in CMA production is unaltered in cmaL mutants. Rather, CmaL is needed for the first step in CMA synthesis, as evidenced by the fact that wild-type levels of coronatine production are restored to a ΔcmaL mutant when it is supplemented with 50 μg/ml l-allo-isoleucine, the starting unit for CMA production. cmaL is found in all other sequenced P. syringae strains with coronatine biosynthesis genes. This characterization of CmaL identifies a critical missing factor in coronatine production and provides a foundation for further investigation of a member of the widespread DUF1330 protein family.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 is a model plant pathogen that causes disease in tomato and the model plants Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana benthamiana (with disease in the latter plant occurring only if the hopQ1-1 gene, encoding an avirulence determinant, is deleted) (1, 2). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 subverts plant immunity primarily through the action of the phytotoxin coronatine (COR) and ca. 30 effectors injected by the type III secretion system (T3SS). COR mimics the plant stress hormone jasmonic acid-isoleucine (JA-Ile) and has multiple activities that promote bacterial pathogenesis, including opening stomata to permit bacterial entry from the surfaces of plant leaves and antagonizing salicylic acid-dependent defense signaling (3–5). COR-deficient mutants exhibit partially reduced bacterial growth in planta and strongly reduced disease-associated chlorosis (6, 7). The T3SS, in contrast, is essential for pathogenesis and is encoded by a cluster of hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenesis) and hrc (hypersensitive response conserved) genes (8). Collectively, the type III effectors, designated Hops (Hrp outer proteins), are also essential for virulence (9). Although individual effectors are dispensable, P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 polymutants lacking certain combinations of a few effectors can have substantially reduced virulence (10–13). A study of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 polymutants lacking effector gene cluster IX (hopAA1, PSPTO4719, hopV1, shcV, hopAO1, PSPTO4723, hopD1′, IS52, hopG1) revealed that PSPTO4723 is essential for the spreading chlorosis associated with bacterial speck disease in tomato (14).

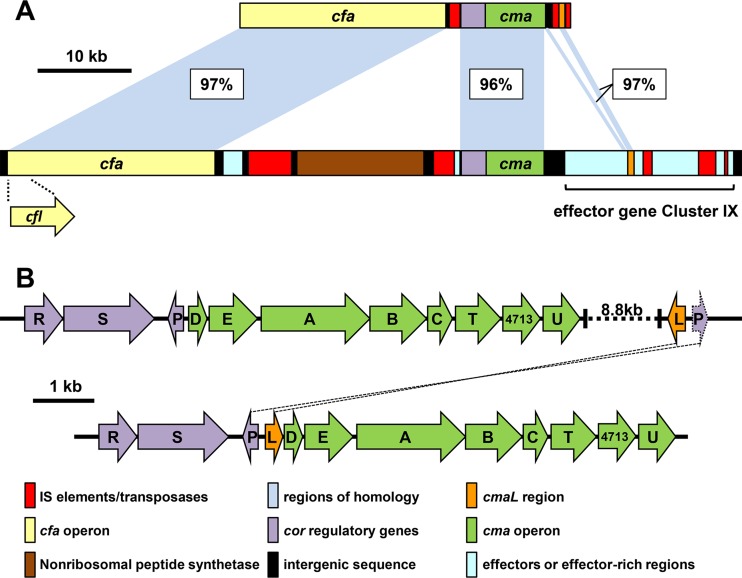

The function of PSPTO4723 was not evident from its genomic context, sequence, or phenotype (14). The gene lacks upstream hrp promoter sequences and coding sequences for N-terminal amino acid patterns associated with type III effectors. It is linked to duplicated sequences of corP, a regulator of COR production, and is further flanked by type III effector genes. BLAST analysis revealed PSPTO4723 to be a member of the DUF1330 family of proteins of unknown function, which are particularly prevalent in Proteobacteria, including those lacking T3SSs. Taken together, these properties suggest that PSPTO4723 is not a type III effector. However, the possibility that PSPTO4723 is an effector cannot be dismissed, because an unknown P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 factor, in addition to COR, can promote chlorosis in infected plants (15). Nevertheless, the most likely role for PSPTO4723 is in the production of COR (14).

Much is now known about COR synthesis (16). Several of the ca. 50 pathovars of P. syringae appear to be capable of producing COR, including pathovars glycinea, tomato, maculicola, atropurpurea, morsprunorum, aesculi, and oryzae (16–18). The pathovars differ largely in host specificity, but COR and other phytotoxins variously produced by P. syringae strains have no apparent role in host specificity. Moreover, many strains of P. syringae pv. tomato do not produce COR (19, 20). The genetics, biochemistry, and regulation of COR production have been studied extensively in P. syringae pv. glycinea PG4180, which encodes COR biosynthesis genes compactly on a 90-kb plasmid (18). In contrast, in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, the COR biosynthesis genes are part of a complex pathogenicity island and are more dispersed (21). COR production has been increasingly studied in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in recent years, particularly its regulation and effects on bacterium-plant interactions.

COR is formed by the amide linkage of two precursors, the polyketide coronafacic acid (CFA) and the ethylcyclopropyl amino acid coronamic acid (CMA) (16, 18). CFA and CMA are produced independently and can be supplied exogenously to restore COR production to corresponding P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants (6, 22). The cfa and cma operons, respectively, responsible for the production of these moieties are separated by 26 kb in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, and it is noteworthy that PSPTO4723 is only 8.8 kb downstream from cmaU, the last gene in the cma operon (21, 23). The cma genes are linked with the corR, corS, and corP genes, encoding a modified two-component regulator system that coregulates the cfa and cma operons (21, 22). Current uncertainties about COR production in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 suggest that PSPTO4723 could be involved in the regulation of COR production, the ligation of CFA and CMA, or the biosynthesis of l-allo-isoleucine, the first step in CMA biosynthesis.

The P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 response regulator CorR regulates the production of both CFA and CMA (22). The corR gene is preceded by hopAQ1, which encodes an unconfirmed candidate type III effector and is itself preceded by a HrpL-responsive promoter (22, 24, 25). HrpL is an extracytoplasmic function (ECF) class alternative sigma factor that regulates the expression of the hrp-hrc T3SS genes and the hop genes (26, 27). In P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, HrpL is needed to produce both CFA and CMA, and intriguingly, CorR is needed to fully express HrpL (22). The dependence of CorR expression on HrpL extends to factors, such as HrpV, that act upstream of HrpL (28), but coordination between the two virulence systems is not fully understood (22). Another intriguing aspect of COR regulation is that cmaE and cmaU show significant antisense expression, which raises the possibility of further regulatory complexities in the production of CMA (29).

The ligation of CFA and CMA depends on the product of cfl (coronofacate ligase [CFL]) (30), the first gene in the cfa operons of both P. syringae pv. glycinea PG4180 and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (31). Cfl shows similarity to enzymes that activate carboxylic acids by adenylation (32), which is consistent with the potential ligation of CFA-adenylate to CMA. However, the role of Cfl is unclear, because it is also required for CFA production (18, 33).

Biosynthesis of l-allo-isoleucine, a diastereomer of l-isoleucine, is another possible role for PSPTO4723 in COR production. The biosynthesis of CMA begins with the activation of l-allo-isoleucine by the nonribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domain of CmaA (34). The complete CmaA/CmaB/CmaC/CmaD/CmaE/CmaT biosynthetic pathway utilizes cryptic chlorination of thioester-tethered l-allo-isoleucine to produce the cyclopropyl ring in CMA. While l-allo-isoleucine is strongly preferred over l-isoleucine as a substrate for the CMA pathway (34, 35), the source of l-allo-isoleucine is unknown (16).

Here we use P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants variously deficient in hrp-hrc genes, PSPTO4723, and cfa and cma genes to explore the role of PSPTO4723. We use N. benthamiana as a test plant because it supports sufficient growth of T3SS-deficient hrp-hrc mutants for COR production in the absence of type III effectors (9, 13). We demonstrate that (i) the contribution of PSPTO4723 to chlorosis in N. benthamiana is independent of T3SS export functions; (ii) PSPTO4723 mutants can cross-feed CFA-deficient mutants but not CMA-deficient mutants in mixed-inoculum plant chlorosis assays; (iii) PSPTO4723 mutants are not deficient in the production of the CMA biosynthetic enzymes; (iv) such mutants accumulate CFA rather than COR in culture; and (v) COR production in culture can be restored to PSPTO4723 mutants by exogenous l-allo-isoleucine. These and other observations indicate that PSPTO4723 plays a role in the production of l-allo-isoleucine. Accordingly, we refer to the PSPTO4723 gene as cmaL below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. P. syringae strains were cultivated on King's B (KB) medium at 30°C (36). Escherichia coli strains were cultivated on Luria-Bertani medium (37). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter): rifampin, 50; spectinomycin, 50; chloramphenicol, 20; gentamicin, 10 for plasmids and 5 for genomic integrants; kanamycin, 50.

Plasmid construction tools.

Plasmids were created as described below and were transformed into E. coli DH5α or E. coli Top10 by standard electroporation or heat shock procedures, respectively (38). Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology. PCRs were performed using Ex Taq DNA polymerase and PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). Restriction enzymes and DNA ligation procedure enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs. Construct sequences were verified through sequencing performed by the Cornell University Life Sciences Core Laboratories Center.

Techniques for transformations and genomic modifications.

Suicide vectors for gene deletions or single-crossover insertions were mobilized into DC3000 backgrounds through conjugation mediated either by biparental mating with the plasmid transformed into E. coli S17-1 or by triparental mating utilizing pRK2013 (39, 40). Deletions created using pK18mobsacB with and without FLP recombination target (FRT) cassettes were performed as described previously (1, 41). Plasmid insertions using pK18mob (42) were selected by plating on KB medium with kanamycin and, when appropriate, spectinomycin. Nonsuicide vectors were transformed into DC3000 backgrounds by electroporation (43). Integrations were checked by PCR and/or by phenotype and antibiotic resistance.

DC3000 mutant strains created for this study.

The regions flanking the cfa operon were amplified by primers p2534/p2535 and p2536/p2537 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) from DC3000 genomic DNA, gel purified (Qiagen), digested with XmaI, ligated together, and then digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into pK18mobsacB to create pCPP5735. A FRT-Spr/Smr cassette, amplified with P2259/P2260 from pCPP5242, was ligated into the XmaI site of pCPP5735 in the reverse orientation to create pCPP5762. pCPP5762 was conjugated into CUCPB5112; integrants were selected on the basis of spectinomycin resistance and were then counterselected on the basis of sucrose sensitivity for vector removal to create CUCPB5532.

The ΔhrcQB-hrcU::ΩSp region of CUCPB5113 (11) was amplified using primers P1296/P2203 and was blunt-end cloned into pK18mobsacB to create pCPP5949. This was integrated into CUCPB5529 (13), and then the vector backbone was removed by counterselection to create CUCPB5540.

The FRTGmR cassette from pCPP5209 was amplified with primer pair p2259/2260, digested with XbaI, and ligated into the XbaI site in pCPP5608 to create pCPP5729. This was conjugated into CUPB5113, and integrants were selected for with gentamicin; then the vector backbone was removed by counterselection to create CUCPB5488. cmaL was deleted from CUCPB5488 as described previously by using pCPP5999 (14) to create CUCPB5570.

The regions flanking the cma operon were amplified from DC3000 genomic DNA with primer pairs P2695/P2696 and P2697/P2698. These flanks were gel purified, digested with SpeI, and ligated together. This ligation product was gel purified, digested with EcoRV, and then ligated into the EcoRV site in pk18mobsacB to create pCPP6017. A FRT-Sp/Smr cassette, amplified from pCPP5242 with primer pair P2259/P2260, was ligated into the XmaI site of pCPP6017 to create pCPP6018. pCPP6018 was conjugated into CUCPB5112, and integrants were selected for with kanamycin; then the vector backbone was removed by counterselection to create CUCPB5591. pCPP6018 was then used in the same manner, but on DC3000, to create strain CUCPB5593.

The regions flanking the genome segment encoding corS to corP were amplified from DC3000 genomic DNA with primer pairs p1063/p1064 and p1065/1066 in a splicing-by-overlap extension (SOEing) PCR (44) that resulted in two ca. 1-kb flanks with a BamHI site engineered in the middle. This was cloned into pENTR-D-TOPO by using an Invitrogen TOPO cloning kit to create pKR36. A FRT-Spr/Smr cassette, amplified with primer pair P1696/1697, was ligated into the introduced BamHI site to create pCPP5265. pCPP5265 and pCPP5215 (45) were recombined by using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen) to create pCPP5266. pCPP5266 was conjugated into DC3000, and integrants were selected for with kanamycin; then the vector backbone was removed by counterselection to create CUCPB5392.

Single-gene-copy complementation of the ΔcmaL mutation for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of COR production was achieved by Tn7-mediated site-specific integration of an approximately 1.1-kb fragment containing cmaL with 500 bp upstream and 300 bp downstream. This fragment was amplified from DC3000 genomic DNA by using primers jnw182 and jnw183 and was ligated into the HindIII site of pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Tc to create pCPP6357. pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Tc and pCPP6357 were used to make specific insertions adjacent to glmS in the DC3000 ΔcmaL genome. Integrants were initially selected on solid mannitol-glutamate (MG) minimal medium with 5 μg/ml tetracycline and were then isolated on solid KB medium with rifampin and 5 μg/ml tetracycline. Insertion into individual isolates was confirmed using primers oSWC461 and oSWC462.

Construction of gene fusions encoding HA-tagged CMA proteins.

Genomic C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged fusions were made by single-crossover integrations into the target genome with a pK18mob derivative containing a ca. 1-kb region of DNA upstream of the respective cma gene stop codon fused to an HA tag sequence. Primers jnw166 to jnw181 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) were used, and the products were first digested with XhoI and then ligated into SalI-digested pK18mob. Single-crossover recombination reactions between the resultant plasmids in the series pCPP6338 to pCPP6345 were integrated into P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and CUCPB5563 to create strains CUCPB6053 to CUCPB6068. Constructs were checked by PCR with a primer upstream of the primed sequence used to create the construct and jnw147, which primes the sequence used to tag all constructs with HA.

A PCR fragment amplified from P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genomic DNA with primer pair p2668/p2712 was digested with BsaAI and XbaI and was ligated into pENTR11 digested with XmnI/XbaI to create pCPP6205. pCPP6205 was LR cloned into pCPP5296 using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen) to create pCPP6206.

Leaf chlorosis assays of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 derivatives.

DC3000 derivative strains were grown on KB medium with appropriate antibiotic selection to maintain plasmids. For individual inoculations, bacteria were scraped from plates, suspended in 10 mM MgCl2, diluted to 3 × 104 CFU/ml, and then inoculated into leaves with a blunt syringe. For cross-feeding coinoculation experiments, bacteria were suspended from the plate in 10 mM MgCl2 individually at a concentration of 3 × 106 CFU/ml each for a total bacterial concentration of 6 × 106 CFU/ml. In both experiments, plants were placed in a 23°C growth chamber with a 16-h day and 90% relative humidity for 6 days to allow symptom development and were then photographed.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR).

Bacteria were inoculated from overnight growth on solid KB medium into KB broth or from solid MG medium (46) into MG broth supplemented with 50 μM ferric citrate at a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 and were incubated for 4 h at 30°C with shaking. Amounts of bacteria equivalent to 1 ml of a culture with an OD600 of 0.4 were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellets were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy minikit from Qiagen, including an on-column DNase treatment. An additional DNase treatment was performed with Ambion DNase I (Invitrogen) by mixing 50 μl of the RNA extract with 5 μl of the buffer supplied and 1 μl of the enzyme mixture and incubating at 37°C for 20 min. This mixture was cleaned with the RNeasy minikit RNA cleanup protocol and was eluted in 50 μl nuclease-free water. RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Scientific) and was diluted to 100 ng/μl.

Reverse transcriptase PCR was performed using qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences). Relative levels of gene expression were assayed in qPCRs using iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The primers for these reactions were designed with Beacon Designer (Premier Biosoft) to give similar reaction results. Primer pair oSWC381/oSWC382 was used to assay the normalizing gene, gap1 (PSPTO_1287, encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), which has been used for this purpose previously in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (26, 29). Primer pair jnw125/jnw126 was used to amplify a short region in the first 1.5 kb of the cma operon. A second primer pair, jnw127/jnw128, amplified a region in the last 1.5 kb of the cma operon and was used to verify that the 3′ end of the operon is not regulated differently under the conditions used for this experiment (data not shown). Cycle threshold (CT) values were used to determine the levels of cma operon transcripts relative to those of gap1 transcripts. The reactions were run and monitored on an iQ5 Multicolor real-time PCR detection system and were analyzed with the software included in the system (Bio-Rad).

HA tag detection.

Bacteria were inoculated from overnight growth on solid KB medium into KB broth or from solid MG medium into MG broth supplemented with 50 μM ferric citrate at a starting OD600 of 0.001 and were incubated with shaking for 24 h at 30°C. Appropriate antibiotic selection was used to maintain any plasmids. Cultures in mid-log growth (OD600, 0.2 to 0.8) were harvested by centrifugation. Bacteria in an amount equal to 1 ml of a culture with an OD600 of 0.5 were boiled directly in 15 μl of a 5×-concentrated sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample loading buffer. Proteins were separated on 4 to 15% acrylamide gradient gels (Bio-Rad) and were transferred to an Immobilon-FL membrane (Millipore). These blots were probed with a rat monoclonal antibody against HA (Roche) diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer, washed, and then probed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Invitrogen), diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer, as a secondary antibody. Blots were visualized using a chemiluminescent reaction and photosensitive film. The images for the production of HA-tagged Cma proteins are all derived without modification from a single blot and immunostaining procedure.

Coronatine production cultures.

Bacteria were grown overnight on solid MG medium. Then they were inoculated into 100-ml MG broth cultures supplemented with 50 μM ferric citrate at a starting OD600 of 0.001 and were incubated with shaking for 72 h at 30°C, after which they were harvested for analysis. For cultures involving the addition of l-isoleucine or l-allo-isoleucine, 5 mg of powder (Sigma) was dissolved in sterile water and then added to 100 ml of culture 24 h after inoculation when the cultures were in late-log phase. At 72 h, all cultures tested were found to have an OD600 of 1.8 ± 0.1 regardless of genotype or amendment. Cultures were separated into cell and supernatant fractions by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Then the supernatants were passed through a 0.2-μm filter and were stored at −20°C until analysis.

Detection of coronatine pathway products.

Production of CFA and COR by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 wild-type, ΔcmaD-U (with deletion of the operon comprising cmaD through cmaU), Δcfl-cfa9 (with deletion of the operon comprising cfl through cfa9), and ΔcmaL strains was determined by quantitative HPLC of extracted culture filtrates. Each replicate sample was extracted from 100 ml of culture filtrate as described previously (47); the organic fractions were rotoevaporated to dryness; and the contents were transferred to a tared vial with methanol and were then dried to a constant weight for analysis. For HPLC, each sample was dissolved in 1 ml of methanol, and then 20-μl injections were used for the analysis. Thus, each injection represents 2 ml of culture filtrate. HPLC employed a Spherisorb Octyl column (5 μm; 4.6 by 250 mm; Sigma-Aldrich), eluted with acetonitrile-water-formic acid (35:65:0.1) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min (Waters 600 pump), with detection by UV absorbance at 208 nm (extracted from a 194- to 450-nm scan on a Waters 996 diode array detector), using standards for the determination of retention times (the COR standard was from Sigma Chemical; the CFA and CFA-isoleucine standards were from C. Bender, Oklahoma State University). Concentrations of COR (retention time, ∼ 9 to 9.5 min) were estimated using a six-point standard curve of COR (0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 μg) to determine peak area units per microgram of COR, and CFA (retention time, 7 to 7.5 min) amounts were estimated using COR peak area equivalents. The limit of detection (LOD), established at a signal-to-noise ratio of 3, was estimated at 50 ng for each standard. Putative COR peaks were confirmed by comparison of spectral scans and coinjection with the standard. The presence of CFA and COR was additionally confirmed by low-resolution electrospray mass spectrometry (LRESIMS) by infusion of sample solutions at 5 μl/min by a syringe pump (Harvard apparatus) into a Micromass ZMD-4000 spectrometer and comparison with standards. Positive-ion spectra were obtained with capillary and cone voltages of 3.5 kV and 50 V, respectively; negative ion spectra were obtained with capillary and cone voltages of 3.5 kV and 45 V, respectively.

RESULTS

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants unable to deliver type III effectors can produce COR-dependent chlorosis in N. benthamiana leaves.

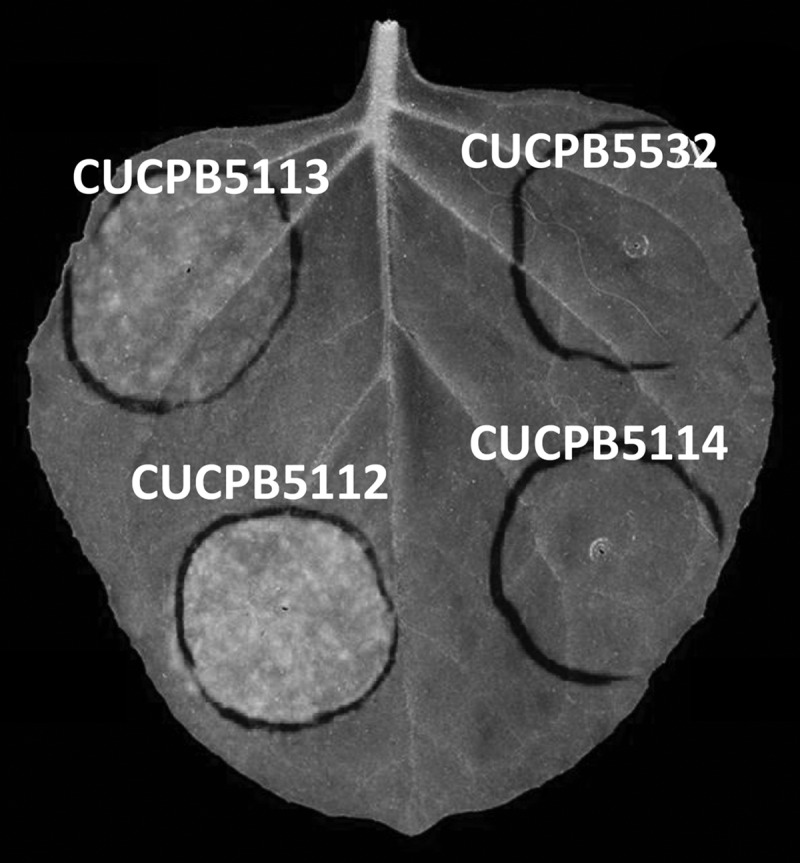

We had noted previously that the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 T3SS-deficient mutant CUCPB5113 produces chlorosis and exhibits significant growth in an N. benthamiana leaf model of infection (9, 13). We inoculated N. benthamiana leaves with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 derivatives with T3SS mutations differing in their regulatory impacts on COR production. CUCPB5113 (ΔhrcQB-hrcU) is deficient in T3SS inner membrane export functions and is not expected to alter COR regulation (11). CUCPB5112 (ΔhrcC::nptII) has a nonpolar mutation resulting from insertion of an nptII gene lacking its promoter and terminator, and this may subtly affect COR production through altered expression of hrpV, which is downstream of hrcC and encodes a negative regulator of hrpL expression (28, 48). CUCPB5114 (ΔhrpK-hrpR::Cmr) lacks the hrp-hrc gene cluster, including hrpL, and therefore is expected to be deficient in COR production (49). N. benthamiana leaves were inoculated with test strains at 3 × 104 CFU/ml and were photographed 6 days later. Chlorosis was observed with CUCPB5113 and CUCPB5112 (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material [in color]). Chlorosis elicitation by CUCPB5112 was stronger, and it was COR dependent, as indicated by its loss in the derivative CUCPB5532 (ΔhrcC Δcfl-cfa9), which cannot produce CFL. These observations confirm that P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 can elicit COR-dependent chlorosis in N. benthamiana in the absence of an active T3SS.

Fig 1.

Chlorosis produced in N. benthamiana by various P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants deficient in T3SS. N. benthamiana leaves were inoculated with the indicated strains at 3 × 104 CFU/ml by use of a blunt syringe and were photographed 6 days later. The strains used were CUCPB5113 (ΔhrcQB-hrcU), CUCPB5112 (ΔhrcC), CUCPB5532 (ΔhrcC Δcfl-cfa9), and CUCPB5114 (ΔhrpK-hrpR). For this and subsequent figures, more-detailed genotypes are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The original color photograph was converted with Adobe Photoshop to gray scale, which shows chlorotic areas to be noticeably lighter.

Chlorosis elicitation by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in N. benthamiana is dependent on CmaL.

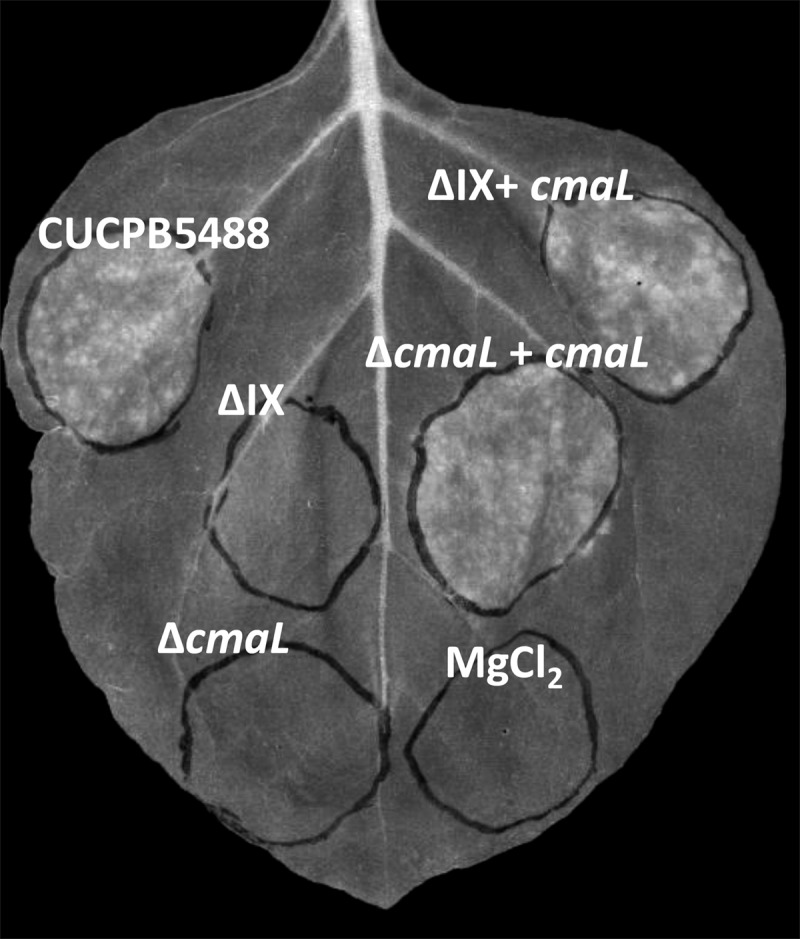

The cmaL gene is located in effector gene cluster IX in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Fig. 2A) and was previously shown to be important for the chlorosis produced in association with disease in tomato (14). Here we introduced cluster IX deletion mutations or ΔcmaL mutations into a ΔhopQ1-1 ΔhrcQB-hrcU background in order to determine whether CmaL makes the same contribution to chlorosis in N. benthamiana that we observed previously in tomato. N. benthamiana leaves were inoculated and photographed as described above. Chlorosis was eliminated by deletion of cluster IX or cmaL and was fully complemented by expression of cmaL alone (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material [in color]). These observations that CmaL promotes chlorosis in N. benthamiana in a T3SS-independent manner suggest that CmaL is important for COR production.

Fig 2.

Arrangement of the COR biosynthesis regions and cma operons in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and P. syringae pv. glycinea B076. (A) Relationship of the cmaL region to the COR biosynthesis genes of P. syringae pv. glycinea B076 (upper diagram), which is most closely related to PG4180 (61), and DC3000 (lower diagram). (B) The DC3000 cma genes and relevant portions of the flanking regions (upper diagram) and their relationship to the proposed location of cmaL as the first gene in an ancestral cma operon (lower diagram).

Fig 3.

CmaL promotes chlorosis elicitation by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in N. benthamiana. Leaves were inoculated and photographed as described for Fig. 1. Restoration of chlorosis promotion to effector gene cluster IX deletion mutants requires cmaL, as shown by the indicated strains, all of which have the ΔhrcQB-hrcU ΔhopQ1-1 background of CUCPB5488 with additional mutations indicated as follows: ΔIX, CUCPB5540 (ΔhrcQB-hrcU ΔhopQ1-1 ΔhopAA1-2-hopG1); ΔcmaL, CUCPB5570 (ΔhrcQB-hrcU ΔhopQ1-1 ΔcmaL); ΔIX + cmaL, CUCPB5540(pCPP6001); ΔcmaL + cmaL, CUCPB5570(pCPP6001).

Mixed-inoculum experiments suggest that CmaL has a function in CMA production.

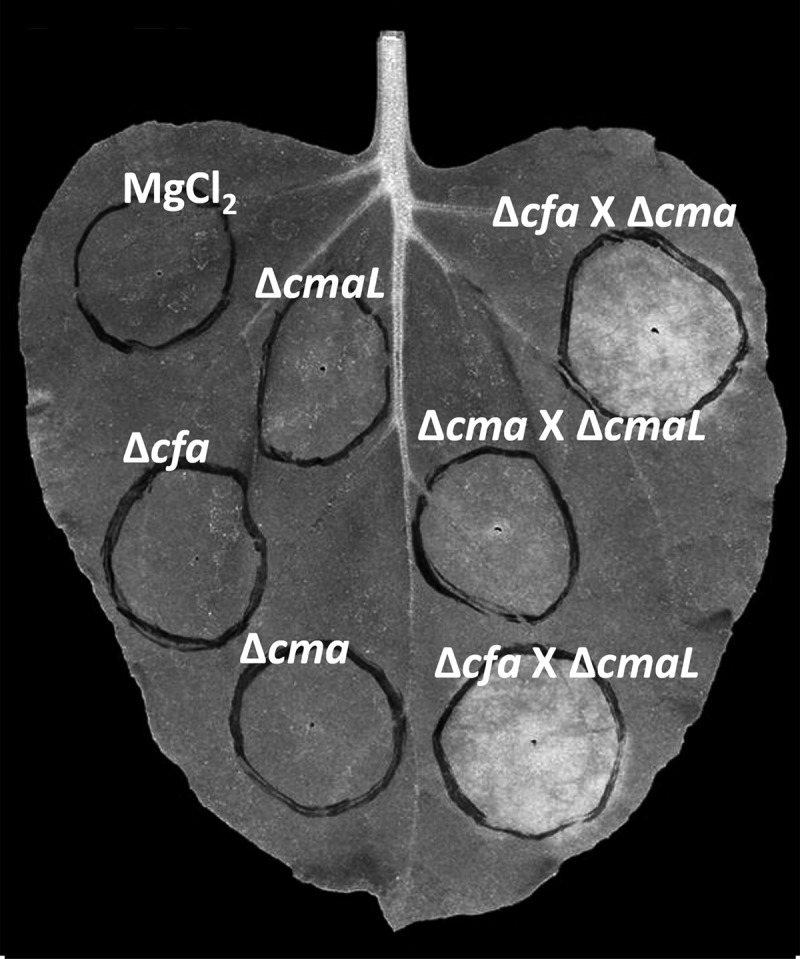

To determine whether CmaL functions specifically in the production of CFA or CMA, we constructed a series of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants lacking cmaL, cfl-cfa9, or cmaD-U in T3SS-deficient backgrounds (ΔhrcC or ΔhrcQB-hrcU). Mutants lacking cmaL, cfl-cfa9, or cmaD-U failed to elicit chlorosis in N. benthamiana (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material [in color]). However, chlorosis was observed following mixed inoculation with Δcfl-cfa9 and ΔcmaD-U strains, demonstrating a capacity for cross-feeding between mutants deficient in complementary pathways. Importantly, in mixed inoculations the ΔcmaL mutant could restore chlorosis elicitation with a Δcfl-cfa9 but not with a ΔcmaD-U partner. These observations are consistent with previous reports of COR production by cross-complementation of cocultured mutants deficient in CFA or CMA (18), and importantly, they suggest that the ΔcmaL mutant is deficient in CMA production.

Fig 4.

Chlorosis induction in N. benthamiana leaves following mixed inoculations with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants deficient in CFA, CMA, or CmaL, implicating CmaL in CMA production. N. benthamiana leaves were inoculated with 3 × 106 CFU/ml of each strain and were photographed as described for Fig. 1. The strains are all T3SS deficient, and “X” indicates a mixed inoculum. ΔcmaL, CUCPB5570 (ΔhrcQB-hrcU ΔhopQ1-1 ΔcmaL); Δcfa, CUCPB5532 (ΔhrcC Δcfl-cfa9); Δcma, CUCPB5591 (ΔhrcC ΔcmaD-U); Δcfa × Δcma, mixed inoculum comprising CUCPB5532 and CUCPB5591; Δcma × ΔcmaL, mixed inoculum comprising CUCPB5591 and CUCPB5570; Δcfa × ΔcmaL, mixed inoculum comprising CUCPB5532 and CUCPB5570.

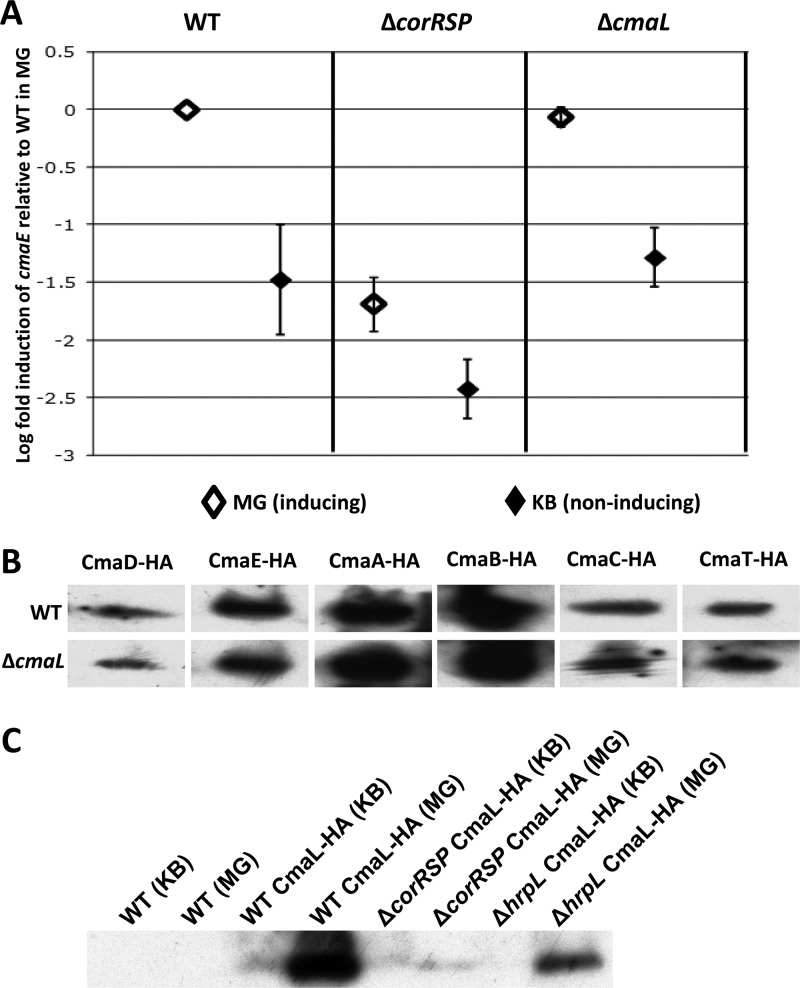

CmaL does not regulate cmaE transcript levels.

We used differentially inducing culture conditions and qRT-PCR to determine whether CmaL has a regulatory role in the expression of cmaE, the second gene in the cmaD-to-cmaU operon (23). To induce COR production in culture, we used mannitol glutamate (MG) minimal medium supplemented with ferric citrate (50). King's B (KB) medium was used as a rich noninducing medium (51). The P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutant CUCPB5392 (ΔcorRSP::FRTSpR) was used as a COR-deficient regulatory mutant control. The cmaE transcript levels in this mutant were compared with those in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and CUCPB5563 (ΔcmaL::FRTSpR). As expected, for wild-type P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, higher levels of cmaE RNA accumulated in MG medium than in KB medium, and this induction was strongly reduced with the ΔcorRSP mutant (Fig. 5A). cmaE RNA levels in the inducing medium were very similar in the wild-type and ΔcmaL strains. Similarly, the ΔcmaL mutation had no effect on the expression of cfl, the first gene in the cfa operon, or on that of cmaU, the last gene in the cma operon (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Thus, CmaL has no apparent role at the transcriptional level in regulating CMA production.

Fig 5.

CmaL does not regulate the production of proteins enabling CMA biosynthesis, and it is produced in a corRSP-dependent manner. (A) CmaL does not affect cma operon transcript levels. cmaE transcript levels were assayed by qRT-PCR after 4 h of bacterial growth in an inducing (MG) or a noninducing (KB) medium. Levels were expressed as abundance relative to levels of the gap1 normalizing transcripts, and then all values were compared to those for the wild type (WT) under inducing conditions. Results are means and standard errors from 4 replicates. Strains are labeled as follows: WT, P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000; ΔcorRSP, CUCPB5392; ΔcmaL, CUCPB5563. (B) Deletion of cmaL does not impact induced levels of accumulation of the six known CMA biosynthetic proteins that are encoded in the cma operon. A gene fusion encoding a C-terminal HA tag was introduced by recombination into cmaD, cmaE, cmaA, cmaB, cmcC, and cmaT in the genome of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (WT) or CUCPB5563 (ΔcmaL). Bacteria were grown for 24 h in MG medium, and HA-tagged protein levels were then assayed by immunoblotting. (C) CmaL production is regulated in a corRSP-dependent manner. Plasmid pCPP6001 carrying cmaL with 200 bp of upstream DNA and encoding a C-terminal HA tag fusion was electrotransformed into various bacteria, which were assayed for accumulation of HA-tagged proteins under inducing (MG medium) and noninducing (KB medium) conditions as described for panel B. Results for strains P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (WT), CUCPB5392 (ΔcorRSP), and UNL134-1 (ΔhrpL) are shown.

CmaL does not regulate the accumulation of CMA biosynthesis proteins.

While CmaL does not regulate the production of the cma transcript, it could still regulate CMA biosynthesis proteins posttranscriptionally. To address this possibility, we constructed C-terminal HA epitope fusions to each of the genes in the cma operon (Fig. 5B). The production of proteins was then monitored by immunoblotting of cell lysates with anti-HA antibodies under inducing conditions. No product was detected for PSPTO4713, a protein with no known function in CMA biosynthesis, or for CmaU, another protein of unknown function, but predicted to be an exporter. The remaining six proteins—CmaD, CmaE, CmaA, CmaB, CmaC, and CmaT—produced detectable fusion proteins. Although the levels of the different HA-tagged CMA proteins differed, despite equal loading of bacterial protein, all six of the CMA proteins were clearly produced in ΔcmaL strains (Fig. 5B). Thus, CmaL has no apparent role at any level in regulating the expression of proteins known to be involved in the conversion of l-allo-isoleucine to CMA.

CmaL is produced in MG (inducing) medium in a CorRSP-dependent manner.

Since CmaL does not appear to regulate CMA production, we considered the possibility of a role for CmaL in the biosynthesis of CMA. If CmaL is essential for the production of CMA, it should be coregulated with the known CMA biosynthesis proteins. We accordingly constructed a gene fusion producing a C-terminal HA tag from plasmid-borne, natively expressed cmaL and examined CmaL-HA production under diagnostic conditions. Immunoblotting of cell lysates with anti-HA antibodies revealed that CmaL-HA was produced only in MG (inducing) medium (Fig. 5C). CmaL-HA production was abolished in the ΔcorRSP mutant, and its level was strongly reduced in the ΔhrpL mutant. Thus, the regulation of CmaL is similar to that of the known CMA biosynthetic enzymes.

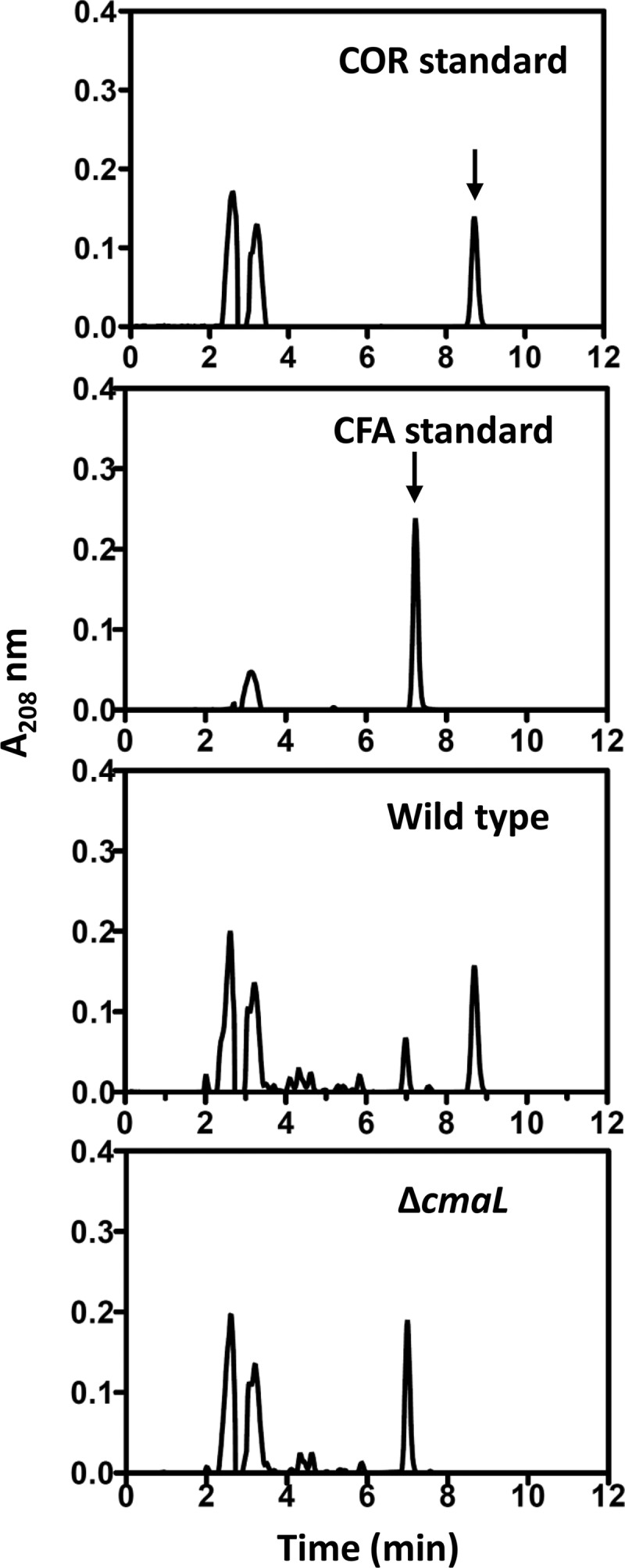

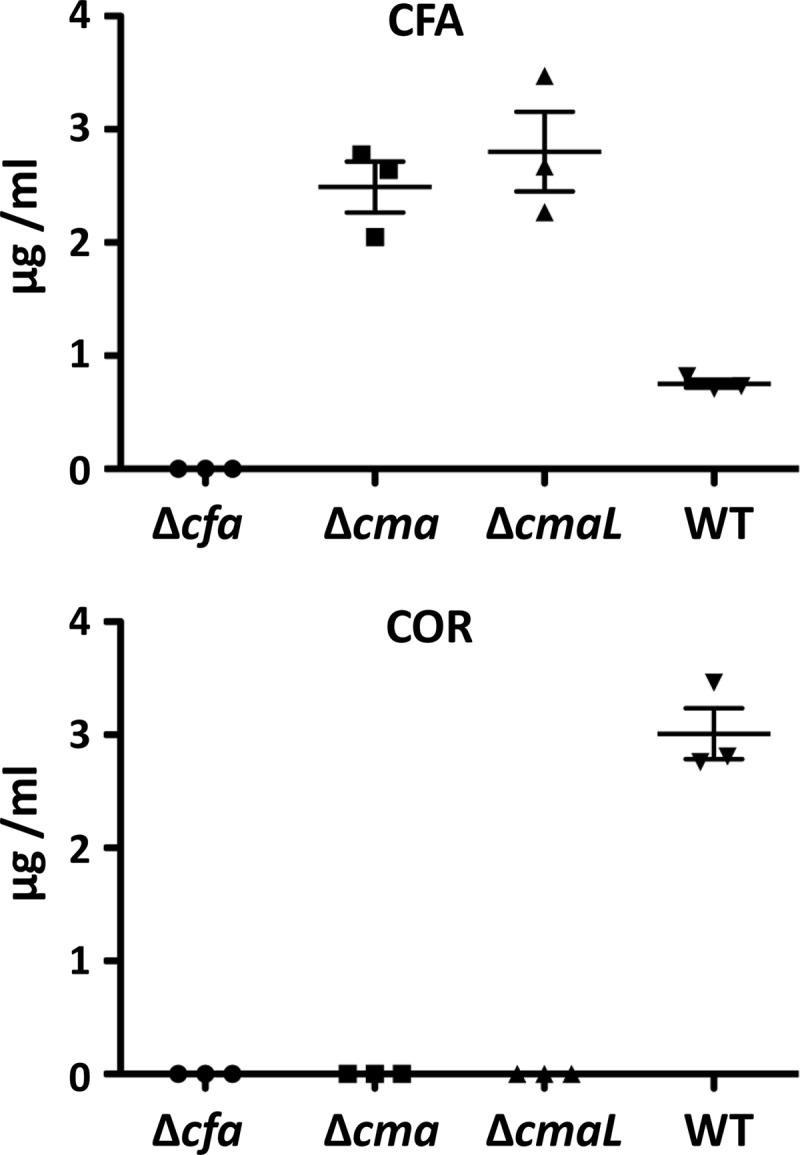

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 ΔcmaL and ΔcmaD-U mutants similarly accumulate CFA rather than COR in culture.

The mixed-inoculum plant chlorosis assays presented above suggested a role for CmaL in the production of CMA but not CFA. To test this directly, we assessed wild-type and ΔcmaL strains of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 for their production of COR and CFA by HPLC analysis of fluids from inducing (MG) medium cultures. COR and CFA were identified by matching the retention times of standards with the peaks in extracts. Wild-type cultures produced COR as a major component and CFA as a minor component of the fermentation broth extract (Fig. 6). In contrast, the ΔcmaL strain produced only CFA. However, Tn7-mediated integration of cmaL with 500 bp of upstream DNA into the genome restored the ability to make COR to the ΔcmaL mutant (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). The analysis of CFA and COR was extended to include the ΔcmaD-U and Δcfl-cfa9 mutants, as well as peak quantification to reveal the relative production of CFA and COR by various strains. As expected, the Δcfl-cfa9 mutant produced no CFA, the wild-type strain produced more COR than CFA, and the ΔcmaL and ΔcmaD-U mutants produced no COR (Fig. 7). In repeated testing, the latter two mutants produced similar levels of CFA. Thus, the ΔcmaL and ΔcmaD-U mutants have deficiencies in COR production that are indistinguishable and consistent with a failure to produce CMA.

Fig 6.

HPLC elution profiles of sterile fluids of wild-type P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and CUCPB5563 (ΔcmaL) grown in inducing (MG) medium reveal that the ΔcmaL mutant accumulates CFA but no COR. Culture fluids were filter sterilized, extracted with ethyl acetate, and analyzed by HPLC.

Fig 7.

Relative levels of CFA and COR produced by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants in inducing (MG) medium reveal that Δcma and ΔcmaL mutants similarly accumulate CFA. Concentrations of COR (retention time, ∼9.5 min) were estimated using a 5-point standard curve, and concentrations of CFA (retention time, ∼7.5 min) were estimated as COR peak area equivalents. Results for strains CUCPB5532 (ΔhrcC Δcfl-cfa9; labeled as Δcfa), CUCPB5593 (ΔcmaD-U; labeled as Δcma), CUCPB5563 (ΔcmaL), and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (WT) are shown.

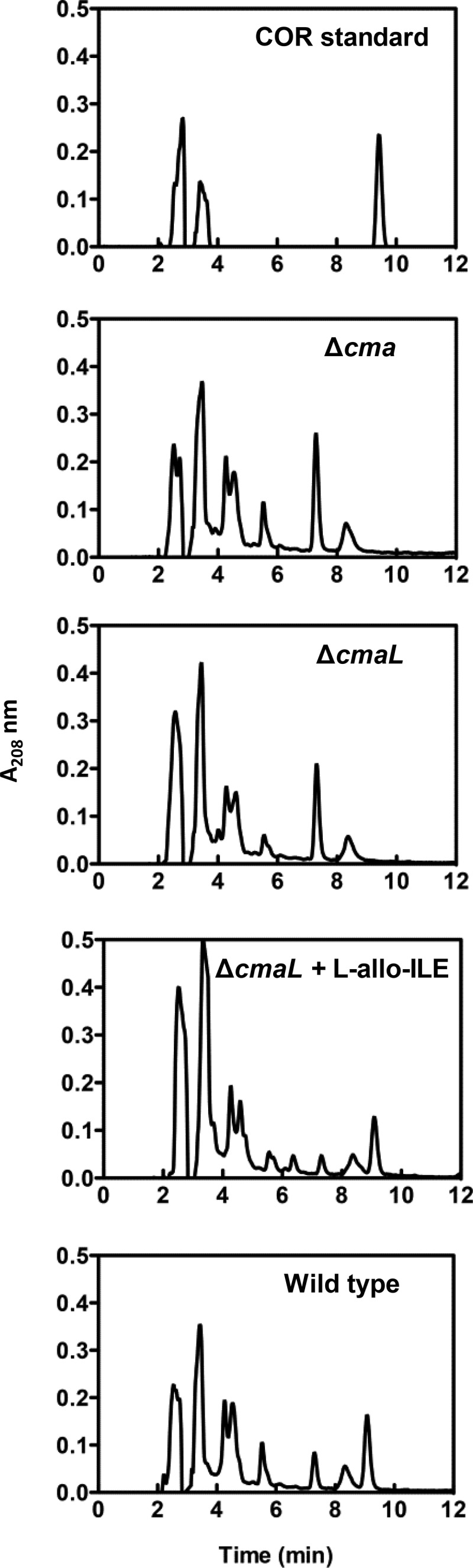

Exogenous l-allo-isoleucine restores COR production to the ΔcmaL mutant.

Given that the mechanism by which l-allo-isoleucine is produced in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and other COR-producing P. syringae strains has not been described, we postulated that CmaL may be required for this function and that ΔcmaL mutants fail to produce CMA and COR because of an l-allo-isoleucine deficiency. Others have shown previously that l-isoleucine is required for CMA production (35, 52, 53) through its conversion to l-allo-isoleucine using radiolabeled precursors (54). To test this hypothesis, we provided l-allo-isoleucine to the ΔcmaL mutant growing in MG (inducing) medium and analyzed culture fluids by HPLC. The supplemented ΔcmaL mutant produced COR, indicating that CmaL is needed for P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 to produce l-allo-isoleucine (Fig. 8). We also used HPLC to determine the effects on COR production of providing the ΔcmaL mutant with l-isoleucine or providing the wild-type strain with either l-isoleucine or l-allo-isoleucine. Exogenous l-isoleucine failed to enable COR production by the ΔcmaL mutant or to increase COR production by the wild-type strain, whereas the provision of l-allo-isoleucine did increase COR production by the wild type (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Importantly, COR production by a ΔcmaL mutant specifically requires l-allo-isoleucine.

Fig 8.

Exogenous supply of l-allo-isoleucine to a P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 ΔcmaL mutant restores COR production in inducing (MG) medium. Bacteria growing in inducing (MG) medium for 24 h were supplemented with 50 μg/ml l-allo-isoleucine. Then, 2 days later, culture fluids were harvested by centrifugation, filter sterilized, extracted with ethyl acetate, and analyzed by HPLC as for Fig. 6. Results for strains CUCPB5593 (ΔcmaD-U; labeled as Δcma), CUCPB5563 (ΔcmaL), and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (WT) are shown.

DISCUSSION

Study of the biosynthesis of COR has yielded several surprises over the years. These include the formation of COR by the ligation of two independently produced moieties (CFA and CMA), the synthesis of CMA by cryptic halogenation using a new type of nonheme-Fe2+-ketoglutarate-dependent halogenase, and the incorporation of an uncommon amino acid in CMA biosynthesis—l-allo-isoleucine, a stereoisomer of l-isoleucine at the beta carbon (16, 18, 34, 54). We have found evidence that CmaL, a DUF1330 protein encoded within a cluster of type III effector genes in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, is needed for the production of l-allo-isoleucine, a molecule for which no enzymatic biosynthesis mechanisms are known. This appears to be the first DUF1330 protein to be implicated in a specific biochemical function, and this finding suggests that proteins in this family may facilitate isomerizations. We discuss below the evidence that CmaL directs l-allo-isoleucine production, properties of the DUF1330 protein family, and the significance of the location of cmaL among type III effector genes rather than with the known CMA biosynthesis genes.

Several lines of evidence suggest that CmaL is involved in l-allo-isoleucine biosynthesis. (i) Although encoded among type III effector genes, CmaL promotes chlorosis independently of the T3SS. (ii) Experiments based on defined mutations in CFA and CMA pathway genes establish that CmaL is specifically needed for the production of CMA. (iii) CmaL makes no contribution to the regulation of the known cma genes but rather is coregulated with them by CorR, which argues against a regulatory role. (iv) A plasmid-borne region in COR-producing P. syringae pv. glycinea PG4180, which carries the cma operon and an essential downstream flank ostensibly containing cmaL, is sufficient to confer CMA production on a nonproducing strain of P. syringae (55), suggesting that CmaL is sufficient to produce l-allo-isoleucine. (v) The proteins of known function in the dimeric alpha/beta-barrel superfamily of proteins (Pfam CL0032), to which DUF1330 proteins belong, are primarily enzymes with small-molecule substrates. (vi) Among 19 sequenced strains of P. syringae recently analyzed for their virulence genotypes (17), cmaL was found only in COR-producing strains. (vii) Most tellingly, supplying l-allo-isoleucine to a P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 ΔcmaL mutant restores COR production.

l-allo-Isoleucine is an uncommon metabolite whose accumulation has been studied largely in the context of maple syrup urine disease in humans, a metabolic disorder leading to the buildup of branched-chain amino acids (56). Two possible reactions have been proposed for the formation of the isomer l-allo-isoleucine (57): first, conversion of l-isoleucine to l-allo-isoleucine by a ketimine-enamine tautomerization, and second, deamination of l-isoleucine to 2-keto-(S)-3-methylvaleric acid followed by keto-enol tautomerization and subsequent reamination. The former reaction was further proposed to involve the activation of l-isoleucine by a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent enzyme followed by nonenzymatic tautomerization, as proposed for l-allo-isoleucine formation in maple syrup urine disease (56). Radiolabeled studies indicate that the second scheme is the primary course of l-allo-isoleucine in humans (57). A particularly relevant example of the tautomerization reaction is the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), a 115-amino-acid phenyl pyruvate tautomerase whose mechanism involves a single proline as the active acid and base in tautomerization (58). Although it is not known how this reaction is occurring in P. syringae, our data indicate that CmaL is involved in the production of l-allo-isoleucine through an as yet unknown mechanism, as an essential step required for CMA and COR production.

The DUF1330 family is typical of DUF families in being less widely distributed than functionally annotated families (59). Distributed mostly in Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, nearly 1,000 proteins with this domain have been identified. The members of this domain family are not associated with pathogenesis, a particular environment, or a particular genetic context. Without this or other corroborating information, there is little basis for preferring one molecular mechanism over another, so no general function for the DUF1330 domain has been defined.

Genes directing COR biosynthesis and the production of the T3SS and effector proteins are part of the flexible genome in P. syringae, which is notable for its high mobile genetic element content and variability among P. syringae strains (60). The linkage of cmaL with duplicated and variously fragmented sequences of corP in all COR-producing strains of P. syringae for which relevant sequence data are available may provide a clue to the evolutionary origins of this arrangement. One scenario is that disruption of an ancestral cma operon resulted in the separation of cmaL from the rest of the CMA biosynthesis genes (Fig. 2B). Evidence for this hypothesis could come from finding the proposed ancestral arrangement in a COR-producing P. syringae strain that has yet to be sequenced. A related question is whether the expression of cmaL independently of the cmaD-U operon offers an advantage that favors the maintenance of this arrangement. Most importantly, further investigations can now focus on CmaL in exploring the mechanism of l-allo-isoleucine production.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kent Loeffler for photography and Eric Markel for assistance with the qRT-PCR.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Plant Genome Research Program grant IOS-1025642.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 November 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01352-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wei C-F, Kvitko BH, Shimizu R, Crabill E, Alfano JR, Lin N-C, Martin GB, Huang H-C, Collmer A. 2007. A Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutant lacking the type III effector HopQ1-1 is able to cause disease in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 51:32–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mansfield J, Genin S, Magori S, Citovsky V, Sriariyanum M, Ronald P, Dow M, Verdier V, Beer SV, Machado MA, Toth I, Salmond G, Foster GD. 2012. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13:614–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melotto M, Underwood W, Koczan J, Nomura K, He SY. 2006. Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell 126:969–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng XY, Spivey NW, Zeng W, Liu PP, Fu ZQ, Klessig DF, He SY, Dong X. 2012. Coronatine promotes Pseudomonas syringae virulence in plants by activating a signaling cascade that inhibits salicylic acid accumulation. Cell Host Microbe 11:587–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooks DM, Bender CL, Kunkel BN. 2005. The Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine promotes virulence by overcoming salicylic acid-dependent defences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 6:629–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks D, Hernandez-Guzman G, Koek AP, Alarcon-Chaidez F, Sreedharan A, Rangaswarmy V, Penaloza-Vasquez A, Bender CL, Kunkel BN. 2004. Identification and characterization of a well-defined series of coronatine biosynthetic mutants of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 17:162–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mittal S, Davis KR. 1995. Role of the phytotoxin coronatine in the infection of Arabidopsis thaliana by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 8:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tampakaki AP, Skandalis N, Gazi AD, Bastaki MN, Sarris PF, Charova SN, Kokkinidis M, Panopoulos NJ. 2010. Playing the “Harp”: evolution of our understanding of hrp/hrc genes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48:347–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cunnac S, Chakravarthy S, Kvitko BH, Russell AB, Martin GB, Collmer A. 2011. Genetic disassembly and combinatorial reassembly identify a minimal functional repertoire of type III effectors in Pseudomonas syringae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2975–2980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alfano JR, Charkowski AO, Deng W-L, Badel JL, Petnicki-Ocwieja T, van Dijk K, Collmer A. 2000. The Pseudomonas syringae Hrp pathogenicity island has a tripartite mosaic structure composed of a cluster of type III secretion genes bounded by exchangeable effector and conserved effector loci that contribute to parasitic fitness and pathogenicity in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:4856–4861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Badel JL, Shimizu R, Oh H-S, Collmer A. 2006. A Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato avrE1/hopM1 mutant is severely reduced in growth and lesion formation in tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin NC, Martin GB. 2005. An avrPto/avrPtoB mutant of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 does not elicit Pto-specific resistance and is less virulent on tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kvitko BH, Park DH, Velásquez AC, Wei C-F, Russell AB, Martin GB, Schneider DJ, Collmer A. 2009. Deletions in the repertoire of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 type III secretion effector genes reveal functional overlap among effectors. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000388 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Munkvold KR, Russell AB, Kvitko BH, Collmer A. 2009. Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 type III effector HopAA1-1 functions redundantly with chlorosis-promoting factor PSPTO4723 to produce bacterial speck lesions in host tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22:1341–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mecey C, Hauck P, Trapp M, Pumplin N, Plovanich A, Yao J, He SY. 2011. A critical role of STAYGREEN/Mendel's I locus in controlling disease symptom development during Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato infection of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157:1965–1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gross H, Loper JE. 2009. Genomics of secondary metabolite production by Pseudomonas spp. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26:1408–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baltrus DA, Nishimura MT, Romanchuk A, Chang JH, Mukhtar MS, Cherkis K, Roach J, Grant SR, Jones CD, Dangl JL. 2011. Dynamic evolution of pathogenicity revealed by sequencing and comparative genomics of 19 Pseudomonas syringae isolates. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002132 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bender CL, Alarcon-Chaidez F, Gross DC. 1999. Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxins: mode of action, regulation, and biosynthesis by peptide and polyketide synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:266–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hwang MS, Morgan RL, Sarkar SF, Wang PW, Guttman DS. 2005. Phylogenetic characterization of virulence and resistance phenotypes of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5182–5191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cai R, Lewis J, Yan S, Liu H, Clarke CR, Campanile F, Almeida NF, Studholme DJ, Lindeberg M, Schneider D, Zaccardelli M, Setubal JC, Morales-Lizcano NP, Bernal A, Coaker G, Baker C, Bender CL, Leman S, Vinatzer BA. 2011. The plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato is genetically monomorphic and under strong selection to evade tomato immunity. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002130 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buell CR, Joardar V, Lindeberg M, Selengut J, Paulsen IT, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Deboy RT, Durkin AS, Kolonay JF, Madupu R, Daugherty S, Brinkac L, Beanan MJ, Haft DH, Nelson WC, Davidsen T, Liu J, Yuan Q, Khouri H, Fedorova N, Tran B, Russell D, Berry K, Utterback T, Vanaken SE, Feldblyum TV, D'Ascenzo M, Deng W- L, Ramos AR, Alfano JR, Cartinhour S, Chatterjee AK, Delaney TP, Lazarowitz SG, Martin GB, Schneider DJ, Tang X, Bender CL, White O, Fraser CM, Collmer A. 2003. The complete sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:10181–10186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sreedharan A, Penaloza-Vazquez A, Kunkel BN, Bender CL. 2006. CorR regulates multiple components of virulence in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:768–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Filiatrault MJ, Stodghill PV, Myers CR, Bronstein PA, Butcher BG, Lam H, Grills G, Schweitzer P, Wang W, Schneider DJ, Cartinhour SW. 2011. Genome-wide identification of transcriptional start sites in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato str. DC3000. PLoS One 6:e29335 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schechter LM, Vencato M, Jordan KL, Schneider SE, Schneider DJ, Collmer A. 2006. Multiple approaches to a complete inventory of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 type III secretion system effector proteins. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:1180–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fouts DE, Abramovitch RB, Alfano JR, Baldo AM, Buell CR, Cartinhour S, Chatterjee AK, D'Ascenzo M, Gwinn ML, Lazarowitz SG, Lin N-C, Martin GB, Rehm AH, Schneider DJ, van Dijk K, Tang X, Collmer A. 2002. Genomewide identification of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 promoters controlled by the HrpL alternative sigma factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:2275–2280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferreira AO, Myers CR, Gordon JS, Martin GB, Vencato M, Collmer A, Wehling MD, Alfano JR, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Lamboy WF, DeClerck G, Schneider DJ, Cartinhour SW. 2006. Whole-genome expression profiling defines the HrpL regulon of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000, allows de novo reconstruction of the Hrp cis element, and identifies novel co-regulated gene. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:1167–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lan L, Deng X, Zhou J, Tang X. 2006. Genome-wide gene expression analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 reveals overlapping and distinct pathways regulated by hrpL and hrpRS. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:976–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peñaloza-Vázquez A, Preston GM, Collmer A, Bender CL. 2000. Regulatory interactions between the Hrp type III protein secretion system and coronatine biosynthesis in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Microbiology 146:2447–2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Filiatrault MJ, Stodghill PV, Bronstein PA, Moll S, Lindeberg M, Grills G, Schweitzer P, Wang W, Schroth GP, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Yang Y, Thannhauser T, Butcher BG, Cartinhour S, Schneider DJ. 2010. Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas syringae identifies new genes, ncRNAs, and antisense activity. J. Bacteriol. 192:2359–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bender CL, Liyanage H, Palmer D, Ullrich M, Young S, Mitchell R. 1993. Characterization of the genes controlling the biosynthesis of the polyketide phytotoxin coronatine including conjugation between coronafacic and coronamic acid. Gene 133:31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang XW, Alarcón-Chaidez F, Peñaloza-Vázquez A, Bender CL. 2002. Differential regulation of coronatine biosynthesis in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and P. syringae pv. glycinea PG4180. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 60:111–120 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liyanage H, Penfold D, Turner J, Bender CL. 1995. Sequence, expression and transcriptional analysis of the coronafacate lipase-encoding gene required for coronatine biosynthesis by Pseudomonas syringae. Gene 153:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rangaswamy V, Ullrich M, Jones W, Mitchell R, Parry R, Reynolds P, Bender CL. 1997. Expression and analysis of coronafacate ligase, a thermoregulated gene required for production of the phytotoxin coronatine in Pseudomonas syringae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 154:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Couch R, O'Connor SE, Seidle H, Walsh CT, Parry R. 2004. Characterization of CmaA, an adenylation-thiolation didomain enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of coronatine. J. Bacteriol. 186:35–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parry RJ, Lin M-T, Walker AE, Mhaskar SV. 1991. The biosynthesis of coronatine: investigations of the biosynthesis of coronamic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:1849–1850 [Google Scholar]

- 36. King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44:301–307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hanahan D. 1985. Techniques for transformation of E. coli, p 109–135. In Glover DM. (ed), DNA cloning: a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1:784–791 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Figurski D, Helinski DR. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:1648–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kvitko BH, Collmer A. 2011. Construction of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutant and polymutant strains. Methods Mol. Biol. 712:109–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schafer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Puhler A. 1994. Small mobilizeable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choi KH, Kumar A, Schweizer HP. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J. Microbiol. Methods 64:391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kvitko BH, Ramos AR, Morello JE, Oh H-S, Collmer A. 2007. Identification of harpins in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000, which are functionally similar to HrpK1 in promoting translocation of type III secretion system effectors. J. Bacteriol. 189:8059–8072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keane PJ, Kerr A, New PB. 1970. Crown gall of stone fruit. 2. Identification and nomenclature of Agrobacterium isolates. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 23:585–595 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Palmer DA, Bender CL. 1993. Effects of environmental and nutritional factors on production of the polyketide phytotoxin coronatine by Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1619–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Preston G, Deng W-L, Huang H-C, Collmer A. 1998. Negative regulation of hrp genes in Pseudomonas syringae by HrpV. J. Bacteriol. 180:4532–4537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fouts DE, Badel JL, Ramos AR, Rapp RA, Collmer A. 2003. A Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 Hrp (type III secretion) deletion mutant expressing the Hrp system of bean pathogen P. syringae pv. syringae 61 retains normal host specificity for tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16:43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bronstein PA, Filiatrault MJ, Myers CR, Rutzke M, Schneider DJ, Cartinhour SW. 2008. Global transcriptional responses of Pseudomonas syringae DC3000 to changes in iron bioavailability in vitro. BMC Microbiol. 8:209 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-8-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li XZ, Starratt AN, Cuppels DA. 1998. Identification of tomato leaf factors that activate toxin gene expression in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Phytopathology 88:1094–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mitchell RE, Young S, Bender CL. 1994. Coronamic acid, an intermediate in coronatine biosynthesis by Pseudomonas syringae. Phytochemistry 35:343–348 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parry RJ, Mhaskar SV, Lin M-T, Walker AE, Mafoti R. 1994. Investigations of the biosynthesis of the phytotoxin coronatine. Can. J. Chem. 72:86–99 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, O'Connor SE, Walsh CT. 2005. Cryptic chlorination by a non-haem iron enzyme during cyclopropyl amino acid biosynthesis. Nature 436:1191–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ullrich M, Guenzi AC, Mitchell RE, Bender CL. 1994. Cloning and expression of genes required for coronamic acid (2-ethyl-1-aminocyclopropane 1-carboxylic acid), an intermediate in the biosynthesis of the phytotoxin coronatine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2890–2897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mamer OA, Reimer ML. 1992. On the mechanisms of the formation of l-alloisoleucine and the 2-hydroxy-3-methylvaleric acid stereoisomers from l-isoleucine in maple syrup urine disease patients and in normal humans. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22141–22147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schadewaldt P, Bodner-Leidecker A, Hammen HW, Wendel U. 2000. Formation of l-alloisoleucine in vivo: an l-[13C]isoleucine study in man. Pediatr. Res. 47:271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stamps SL, Taylor AB, Wang SC, Hackert ML, Whitman CP. 2000. Mechanism of the phenylpyruvate tautomerase activity of macrophage migration inhibitory factor: properties of the P1G, P1A, Y95F, and N97A mutants. Biochemistry 39:9671–9678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. 2012. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:D290–D301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lindeberg M, Myers CR, Collmer A, Schneider DJ. 2008. Roadmap to new virulence determinants in Pseudomonas syringae: insights from comparative genomics and genome organization. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21:685–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Qi M, Wang D, Bradley CA, Zhao Y. 2011. Genome sequence analyses of Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. glycinea and subtractive hybridization-based comparative genomics with nine pseudomonads. PLoS One 6:e16451 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.